By Eric Niderost

On Friday, September 28, 1473, Charles, Duke of Burgundy arrived at Trier to meet with the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III. Trier, nestled along the banks of the beautiful Moselle River, had been founded by the Romans, and as the oldest city in Germany had seen much in its 1,400-year history. Though the city’s merchants and craftsmen were used to visiting dignitaries, they thronged the streets eager to witness the pomp and pageantry of the Duke’s arrival. Charles was something of a legend in his own time, a man whose wealth and power equaled, if not surpassed, Europe’s greatest potentates.

The Emperor and the Duke met just outside the city, but before they made their triumphal entry through the main gate there were a few last-minute items to iron out. There was the matter of who would take precedence in the procession. Weak and often vacillating, Frederick probably feared the mighty duke, but hid his qualms behind a façade of imperial dignity. The Emperor felt he should take the lead, and Duke Charles follow. After all, in feudal terms, Charles was his vassal.

The two men argued for a half an hour but, predictably, Charles had his way: the pair would ride in side by side. In a world where hierarchy was all, and symbolism often reflected political realities, riding with the emperor implied that Charles was Frederick’s equal. It was a point that was not lost to the thousands who turned out to witness the spectacle.

The procession featured armored soldiers whose glistening breastplates were covered in cloth of gold, and trumpeters in white and blue carried silvered instruments. But the most impressive of all were the heralds of the various states that acknowledged Charles as sovereign. Their coats bore the armorial designs of each duchy, county, or territory in his vast realm, a blaze of color and intricately embroidered design. But it was the Burgundian flag that put it all into perspective—emblazoned with the diagonal stripes of old Burgundy, the fleur de lys of France, the red lions of Brabant and Limberg, and the black lion of Flanders.

Charles himself dazzled his onlookers with armor so polished it shone like the sun. Over the armor was a mantle embroidered with diamonds and other precious stones that was rumored to be worth 200,000 gold crowns. To top it off, literally and figuratively, his hat was a velvet cap ornamented with a diamond so large no one could even speculate as to its value.

It seemed as if Charles wanted to overwhelm the Emperor with displays of wealth and power. Indeed, as the weeks went by a steady procession of embassies—from the various Italian and German states, England, and even far-off Hungary—came to Trier to pay court to Charles, not Frederick. But the thing Charles coveted most was to be crowned king of Burgundy, something only the emperor could grant.

Charles belonged to the House of Valois-Burgundy, a branch of the royal Valois dynasty that currently ruled France. Philip the Bold, Charles’s great-grandfather, had been the first Duke of Burgundy, a title given to him by his father, King John of France. Originally Burgundy was just a moderately large province in northeastern France, and during Philip’s tenure relations with France were good. But under the next two dukes, John the Fearless and Philip the Good, Burgundy grew in wealth and power, and family ties took a back seat to political rivalry and growing ambition.

Burgundian possessions continued to grow, through inheritance, marriage, conquest, or even purchase. Burgundy eventually controlled Flanders and most of the low countries, much of which is Belgium and the Netherlands today. In the late middle ages the low countries were economic powerhouses, dynamic centers of trade and nascent capitalism. Above all, the wool trade made Flemish cities rich, with textile workers producing cloth that was a much sought-after commodity.

But ducal possessions were scattered, with the original Duchy of Burgundy far from the dynamic wool centers in Flanders. By the time Charles had come to power, it was his overriding ambition not just to be king, but king of a contiguous state strategically located between France and the Germanic Holy Roman Empire. His father Philip the Good had been a patron of the arts, commissioning and encouraging artists to produce works that were the envy of Europe. The Dukes of Burgundy were kings in all but name; Charles wanted a title commensurate with his power and wealth.

Perhaps a bit cowed by his powerful guest, Frederick agreed in principle that Charles should be king. It was said that royal regalia had been prepared for Charles’s elevation, and a date had been set. But at the last minute, Emperor Frederick departed Trier without even saying farewell to his illustrious guest. Frederick’s departure put the idea of Charles’ coronation on hold. Angered by the Emperor’s flight, Charles comforted himself with the notion that this was only a temporary setback.

Some of Burgundy’s neighbors viewed Charles’s ambitions with alarm. One of these was the Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaff (Swiss Confederation). The Confederation was something of an anomaly in the 15th century, a group of proudly independent free states without a feudal lord demanding loyalty and tribute. The Swiss were not yet a nation in the modern sense, but rather a group of independent cities and Cantons that banded together for mutual support and defense.

The alliance was started in 1291 with the three so-called forest cantons—Uri, Unterwalden, and Schwyz on the shores of Lake Lucerne. More states, including Glarus, Zug, Zurich, Lucerne and Bern had been added by the 15th century. The Swiss knew Charles had designs on the neighboring Dutchies of Lorraine and Savoy, even though their current rulers were nominal friends of Burgundy. Swiss merchants also feared Charles would deliberately block or otherwise interfere with their trade routes.

Sooner or later, the Swiss feared, their lands were bound to be coveted by the rapacious Duke. When would Charles be satisfied with his territorial acquisitions? For their own protection the Swiss Confederation formed an anti-Burgundian alliance that included Rene II, the embattled Duke of Lorraine, Sigismund of the Hapsburg dynasty, and eventually King Louis XI of France.

Truly, politics did make strange bedfellows, especially when it came to Sigismund and the Swiss. The Hapsburgs were a traditional enemy of the Swiss, an enmity that dated back to the “forest cantons” period when the former tried to impose its will on the stubborn mountaineers. But when Sigismund was short of cash he pawned one of his holdings, Alsace, for 50,000 florins, with the option—he thought—of buying them back.

But when Sigismund, his wealth restored, tried to redeem Alsace, Charles refused. As far as the Duke of Burgundy was concerned, Alsace was his, in perpetuity. Charles kept the province—but gained a new enemy in the Hapsburg prince. Their coalition forming, the Swiss formally declared war on Burgundy in October, 1475 by sending a herald to the Duke. The herald announced that “We declare to your most serene highness, and to all of your people, on behalf of ourselves and our friends, an honorable and open war.”

This war was going to be a clash of military titans. Charles realized that feudal levies were inefficient and mercenaries were costly and slow to muster. The Duke still used both—he had little choice—but had gradually started to think of raising a standing army. In 1467, after a campaign against Liege, Charles asked his captains if any of their men would like to extend their military services beyond the usual period. Basically he needed men to garrison the Liege area, but the precedent was established, and grew over time.

Charles devoted himself to the minutiae of military affairs, and even his worst enemies admitted he had a flair for organization. The Duke issued a series of ordonnances that outlined what he expected in terms of discipline, weaponry, clothing, and general administration. The “lance” was the basic administrative unit, and referred not to an individual knight or man at arms, but to a grouping that included no less than three mounted archers, a swordsman “coustillier” armed with a javelin and sword, and even a page.

The man at arms need not be a knight, but usually came from a family —son of a merchant, for example—that had the means to buy expensive armor. These groupings were relics of the old feudal order, for administrative purposes, and did not fight together as a unit.

The “lance” also included one crossbowman, one pikeman, and a hand-gunner. The latter’s weapon was a primitive firearm that was essentially a brass or iron tube. It was clumsy to handle, in part because the gunpowder was not encased in cartridges, a technique which came later in the period. The guns didn’t have a true stock, but were set on a long wooden stave that was held under the arm as the gunner applied a burning match to the vent.

The war opened with a Swiss victory over Burgundian and Lorraine forces at Hericourt. Charles was not present at Hericourt, but felt this was a blow to his prestige. Worse was to follow. The Swiss easily routed Jacques of Savoy, Count of Romont in the Savoyard-held provinces of Vaud and Valais. It was a stinging reverse for Charles, especially since the Swiss would block access to Italian mercenaries that the duke used.

He could have fallen back to the low countries, but decided to take the offensive in 1476 while Europe was still in the grip of winter. The duke tended to be impulsive, selfishly wanting his own way immediately, regardless of consequences. His nickname was Charles le Temeraire, usually translated as “the Bold,” but in French it is closer to “the Rash.” Not even the news that his ally, Duke Galeazzo Sforza, had decided not to send Milanese troops against the Swiss would change his mind.

Charles began moving his armies south from Germany, his intention to occupy several key towns and castles along Lake Neuchâtel. Once these positions were secured, they would form a base from which he could launch an invasion of the Swiss Canton of Berne. All of the Swiss Confederation were troublesome irritants to him, but Berne, in particular, was a thorn in his side.

Canton Berne had a pretty good idea of what the Duke might do, as well as his probable routes, so it lost no time in evacuating Yverdon and strengthening the garrison at Grandson. As expected, Duke Charles appeared before Grandson with his army and put the town and its castle under siege.

The city walls were easily breached, and as Burgundians soldiers poured into Grandson, the beleaguered garrison fell back towards the town castle for refuge. The castle boasted thick walls and its battlements bristled with cannon. Grandson Castle was formidable, but Charles boasted the largest, and quite possibly the finest, artillery train in Europe. Burgundian bombards were set up and maintained such a steady fire the castle defenses were pounded into ruins.

On the night of February 23-24, two Swiss messengers were lowered over the walls and successfully passed through the Burgundian siege lines. When they reached safety the tale they told was a harrowing one. The castle’s master gunner had been killed, ironically beheaded by a cannonball, and there was no one to replace him. The castle magazine had blown up, reducing stocks of gunpowder, and the subsequent fire did further damage.

Food was running out and the garrison was reduced to eating unground grain. Soon even that would be gone, and sheer starvation would compel them to surrender. A relief force of several ships were assembled and tried to reach the garrison via Lake Neuchâtel, but the effort failed. Burgundian artillery fired on them from the shoreline, and the Duke’s superior ships soon forced them to retreat.

But as the news of Grandson spread through the Cantons, the Swiss began mobilizing for a relief army to confront Charles. Swiss troops laid siege to Vaumarcus castle, located further up Lake Neuchâtel, in order to draw the Burgundians away from the Grandson area. But then they received the news that Grandson had surrendered unconditionally with the expectation of quarter. That belief was tragically mistaken, as Charles had determined to execute them all, regardless of age or rank.

The 15th century was a brutal age, where ideals of chivalry and knightly honor were often given lip service, but rarely followed. Charles the Bold was no exception. A few years earlier, when the rebelling city of Dinant had mocked him as a bastard, and implied his mother had loose morals, it was said Charles took revenge by slaughtering the whole population, including women and children. Grandson was no exception, but this atrocity seems to be a deliberate act of terrorism.

The victims were paraded past Charles’s tent, then hanged on nearby trees or drowned in Lake Neuchâtel. The grim process took over four hours to accomplish. The killings were supposed to frighten the Swiss, make them submit in terror, but like the Alamo centuries later, it had the opposite effect. The Swiss were outraged, swearing to avenge their slaughtered countrymen.

The Swiss army, some 20,000 strong, marched through the forests of the Jura mountains in search of the Burgundians. The Swiss Confederation had very few cavalrymen, but their infantry was considered the best in Europe. Most were halberdiers and pikemen. In fact, pike formations had dominated the battlefield for the last half of the 15th century. The pike was most effective in massed phalanx formations, similar to the ones associated with the ancient Greeks.

The pikes were generally 14 to 18 feet in length, and it took constant drill and firm discipline to keep the ranks of the prickly “hedgehog” formations tightly packed.

The Swiss marched on, breath misting in the cold mountain air as they sang songs and trudged through snowy alpine meadows. The concept of Swiss nationhood may have been embryonic, but it was there, and would grow in time. They were united in their opposition to Charles, and the feeling of hatred flared anew with the Grandson atrocities.

In the meantime Charles was advancing along Lake Neuchâtel, until forward elements reached a hamlet called Concise, about 4.5 miles from Grandson. There was a temporary halt while the Burgundian Vorhut—the van—started pitching tents and setting up camp just west of Concise. The camp was on a slope that extended through dormant vineyards to a line of woods.

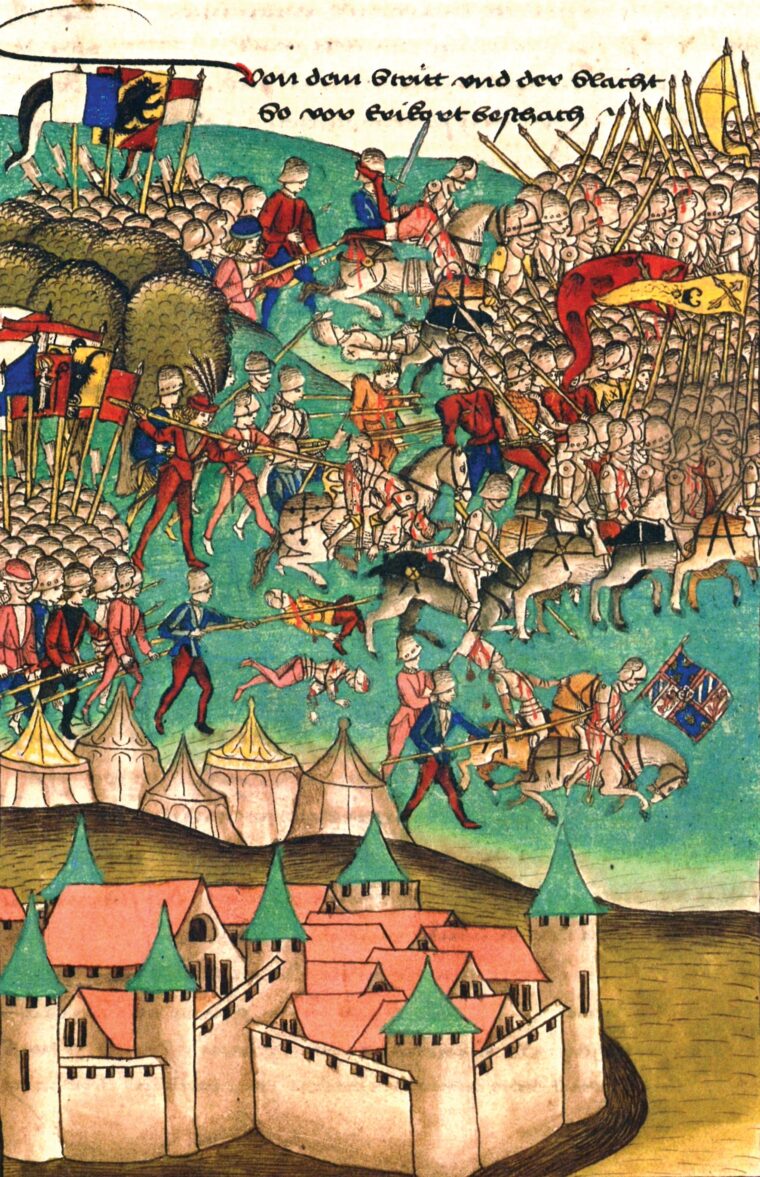

About 100 foraging Swiss soldiers suddenly appeared, and a brief skirmish ensued. Charles, now alerted, formed up his own troops for battle and ordered elements of his infantry up the slopes to engage the Swiss, whose Vorhut had also come up. The skirmishing grew heated, with the Burgundian archers getting the worst of the encounter. The battle of Grandson, March 2, 1476, was about to begin.

More Swiss troops arrived, including the Bernese, Solothurn, and Fribourg contingents, until the Confederation army had around 10,000 effectives at this point; Duke Charles had about 20,000. The Swiss commanders gave the order to halt, but the rank and file would have none of it—“Grandson! Grandson!” was the cry that emerged from hundreds of throats. The soldiers wanted to come to grips with the ruthless enemy who had so brutally killed their brothers.

Bowing to popular pressure, the commanders ordered an advance. A group of about 300 hand gunners and crossbowmen—mainly Bernese, Schwyzer and St. Gallen—were sent out as a new skirmishing “forlorn hope” while the main body formed a gevierte ordnung, or squared formation. Ensigns carrying some 30 standards formed the core of the formation, their colorful kaleidoscope of banners standing out in the chill morning air.

Men carrying halberds, boar spears, and other short-hafted weapons surrounded the standard bearers, and they in turn were surrounded on three sides by eight rows of pikemen—many, but not all, in full armor. Each Swiss soldier was obligated to purchase his own armor, and the poorer men had to do with whatever they could afford, including “hand me downs” and older style odds and ends.

The Swiss phalanx formations were a formidable sight and in the center it was said one of their commanders, Nicklaus von Scharnachtal, with his flowing beard and long tunic, was just as striking. Hauptmann Ulrich Karzy of Schwyz was also notable among the officers. Bernese cannon provided artillery support, though the Burgundian guns far outmatched them in quantity.

The Burgundian army was a polyglot force consisting of Flemish and French men at arms (gendarmes), pikemen, Italian crossbowmen, English longbowmen, and German gunners. Most of them fought for pay and few, if any, had any real allegiance to Charles or faith in his cause.

The Burgundian army also presented an impressive display of military might when drawn up in full battle array. Encased in armor, the Burgundian men at arms and their mounts were dazzling in the morning sun. There was a degree of uniformity, too, because their helmets had white and blue plumes, something that Charles insisted each man at arms display.

One of the main Burgundian emblems was the so-called red “ragged staff,” a saw-toothed St. Andrew’s Cross. Each soldier wore a plain red version of the St. Andrew’s Cross, usually in the center of his chest. Though it was a good means of identification—when the concept of uniforms was still in the distant future—Swiss crossbowmen must have found it a convenient target.

But before the battle commenced the whole Swiss army got down on their knees and began to pray, invoking God’s help in the coming contest. The Burgundians, watching the curious spectacle from afar could hardly believe their eyes. It was a violent age, but in this period virtually all western Europeans were pious Catholics. Charles himself regularly had his armies shout inspirational battle cries evoking heavenly aid. The Duke himself wrote that before one clash “We gave the cry of “Notre Dame! ( Our Lady, Mary, mother of Jesus), and Monseigneur St George!”

But the Swiss were doing something very different—10,000 men on their knees praying to the Almighty. The Burgundian astonishment turned to derision, then laughter. Some Burgundians even thought that the Swiss were surrendering, on their knees begging for mercy.

But once the prayers were over, the Swiss rose as one man and stood silently, waiting for the signal to advance.

The signal was not long in coming, and Burgundian laughter soon ceased as 100 Swiss drums began to beat a throbbing tattoo that stirred the blood and quickened the pace. It was about 10 a.m.—some sources say 11a.m.,—and the battle of Grandson was about to begin. Charles began the fight with a massive barrage from his artillery, all but drowning out Swiss drumming with thunderous roars. The shot largely passed over the “forlorn hope” Swiss vanguard, causing grievous harm whenever they hit a phalanx formation trailing behind.

One projectile crashed into the tightly packed phalanx with such force it killed and horribly wounded 10 men in one section. Yet by some accounts the Burgundian guns were not as effective as they could have been, because of the hilly nature of the ground. In any case, the Swiss artillery—Bernese culverins in this case—flamed in counter-battery and also did some damage.

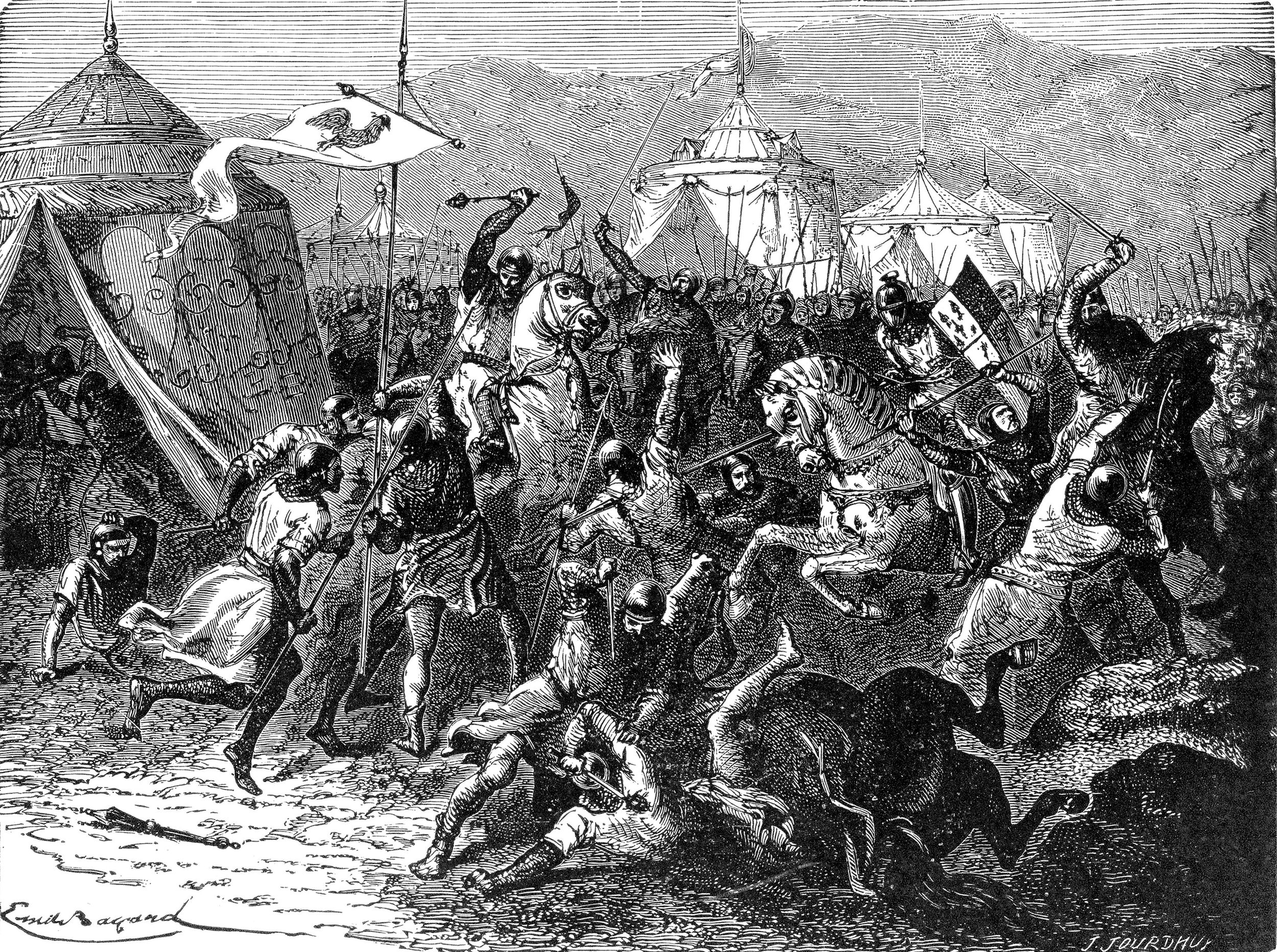

Impulsive as always, Charles decided the Swiss were softened up enough by his cannon to be finished off by his cavalry. The Duke ordered a cavalry charge, and the armored warriors, lances couched under their arms, spurred their horses into a gallop. Their first target was the “forlorn hope” vanguard of hand-gunners and crossbowmen, who initially held their ground in the face of the surging tide of armor, steel, and horseflesh. Depending on the thickness of the steel and how close the target was, crossbow bolts could pierce armor and this proved the case at Grandson.

The crossbowmen and hand-gunners unleashed a final storm of missiles before falling back to the safety of the phalanx just behind them. Bolts fell on the advancing cavalry like a deadly hail, and when they found their mark horsemen tumbled from the saddle. Horses were also felled, in spite of their protective armor. But the charging mass of cavalry was coming on too fast for another volley; so the gunners and crossbowmen turned around and ran for the safety of the phalanx.

Most did reach the phalanx in time, and once the pike barrier was lowered it was all but impenetrable. Horses reared and plunged, unable or unwilling to breach the prickly barrier. Now protected by the pike wall, the crossbowmen reloaded and fired again and again into the densely packed mass. At such close range the crossbow bolts easily penetrated the armor of horse and rider alike.

One desperate Burgundian spurred his horse forward into a jump and landed right in the midst of the phalanx ranks. He was quickly dispatched, but his passage left a momentary gap in the lowered wall of pikes. Another horseman took advantage of this break and pushed his way deeply into the phalanx. Flailing away with his sword, he spied the banner of Schwyz just ahead and attempted to capture it.

It was an act of suicidal bravery, but the horseman managed to grab the brown, blue and white banner’s flagstaff from the ensign carrying it before the Swiss soldiers closed in. A Swiss halberd axed his horse, which dropped immediately, and moments later a pike was driven through his breastplate with such force the point emerged from his backplate.

It was only later that the Swiss realized that the rider was Ludwig von Chalon Chateau Guyon, one of the most prominent of Burgundy’s cavalry commanders. The horsemen who survived the charge galloped back to Burgundian lines, their mission a failure. There was now a brief pause while the Burgundians regrouped and the Swiss took stock of the situation. The ground in front of the phalanx was a horrible sight, a field of broken pikes fouled with the blood of dead and wounded men and horses.

For all his faults, no one ever accused Charles of the Bold of cowardice. After his men at arms reformed, Charles decided to use a wedge formation of heavily armored mounted men at arms to break the phalanx, The Duke himself would lead the charge, resplendent in his shining armor, and it’s possible he even wore an open surcoat that displayed his heraldic arms. But pageantry wasn’t going to break the pike wall and the Duke soon found the bloody debris from the first charge slowed the impetus of the second.

Unable to break the phalanx, the Burgundian cavalry again withdrew. Though Charles had a horse killed under him, he was unscathed. Luckily for the headstrong duke, a fresh mount was available and he galloped away to join the rest of his horsemen. Now frustrated, the Duke committed a grave error. He ordered his artillery, which had started to open fire and was decimating Swiss ranks, to withdraw to the flanks, while the rest of his infantry fell back slightly

The idea apparently was to lure the Swiss forward, away from the slopes and grape vines that hindered cavalry movements. Once on more level ground, the Swiss phalanx would be more vulnerable to flank attacks by Burgundian cavalry, because the latter would have more room to maneuver. There was even a possibility that the Burgundian horsemen might get around the phalanx and attack the rear. But as the Burgundian army began its planned withdrawal, Swiss reinforcements appeared on the battlefield.

There were two main routes to the Concise region: an upper road and a lower road closer to the lake. The men of Lucerne, Uri, and Unterwalden had marched along the upper road, while the soldiers of Zurich, Glaris, Zug, Schaffhausen, Strasbourg, and Basle had marched along the lake. The battle-weary Swiss on the field took heart at the arrival of their comrades in arms, and before long the newcomers were integrated into the already existing formations.

The great Hartshorner of Lucerne sounded a deep, almost rumbling, roar that was joined by other Swiss war horns in the assembled army. Loud and compelling, the music stirred the blood of the Swiss. For the Burgundians, it was more like a funeral dirge that foretold their approaching doom. The Swiss army started to advance, and as they moved forward thousands of men began to shout “Grandson! Grandson!”

The arrival of additional Swiss troops had caught Charles and the Burgundians off guard, as they were under the mistaken impression that the men they had been fighting since late morning were the entire Swiss army. The shock of these additional Swiss soldiers caused consternation in the Burgundian ranks and planted the seeds of panic. The arrival also coincided with the Duke’s planned withdrawal, which to the uninformed looked like a headlong retreat.

Burgundian soldiers started to break formation and run away, and before long the trickle of escapees became a flood. The camp followers joined the stampede, spreading the panic to units that had not been affected. Charles, incredulous, shouted orders to stand, but he was ignored. The Duke, his frustration working up into a boiling rage, began hitting the fleeing soldiers with the flat of his sword, but to no avail. The retreat had turned into a total rout.

His passion spent, the Duke finally began to calm himself, and a handful of faithful retainers and men at arms managed to persuade him to withdraw. Charles was one of the last Burgundians to quit the field.

The Battle of Grandson was over. It was a triumph for the Swiss, who lost some 500 men. The Duke’s army saw about 1,000 killed, with more Burgundian corpses floating on the lake. But the defeat created shock waves that reverberated throughout Europe. Charles the Bold, arguably the greatest potentate in Europe, possessing a huge army and the finest artillery train in existence, had been defeated by sturdy peasants and mountaineers.

The aftermath was long remembered by the Swiss soldiers who had participated in the fight. One of the first things they saw were the corpses of the Grandson garrison, still hanging by the dozens on tree branches. The Swiss recognized neighbors, friends, and even relatives swaying in the wind, faces distorted and showing signs of decay. Each dangling corpse had a name, a family, and loved ones back home that would be devastated by the news. Enraged by the sight, Swiss soldiers killed the Burgundians they had captured.

Captured intact, the Burgundian camp was a wonder to the Swiss—pavilions and tents filled dazzling riches the likes of which the Swiss soldiers, especially the rank and file, had never seen The tents of the princes and high status nobles were richly embroidered, with colorful flags and banners fluttering in the breeze, symbols of the wealth and power of their owners.

But the rich exteriors only hinted at what lay inside. There was silver tableware, elaborate armor, jeweled ornaments, and stacks of gold coins piled everywhere. But the grandest of all was the tent complex of Charles the Bold himself. He had intended to literally hold court when he pushed on to Savoy, so he brought along everything he felt he needed for such a regal occasion.

There was a richly decorated chapel, and regalia for state occasions. Particularly noteworthy was the sword of state, covered in sculpted gold, large gems, and pearls. The Burgundian state seal was also left behind, encrusted with one pound of solid gold. Charles’s hat, the one with the large diamond that he wore in Trier, was also in his tent. And there were gold and silver coins scattered about and works of art from the various Dukes of Burgundy that had preceded Charles. Even allowing for the possibility of holding court, why Charles chose to take so much of the art and wealth of Burgundy will remain unknown.

The Swiss also discerned there were liquid spoils as well. There was cask after cask of good Burgundian wine, and the soldiers lost no time in drinking copious amounts to celebrate their victory. Necessity is the mother of invention: the Swiss took the smallest guns (Feldschlagen), put stoppers in the touch-holes, and made makeshift tankards to drink the wine.

But there were more surprises in store for the rough-hewn craftsmen and peasants of the Swiss army. There were over 2,000 prostitutes still in camp, each wearing colorful low cut dresses that aped court fashions. They spoke no German, and most of the Swiss spoke no French, but when one of the Swiss who did know French asked one of them “Qu’avec vous a offrir, mes dames?” (What are you offering?), she lifted her skirts in a provocative manner. No further translation was necessary. It was said some later even became wives to the Swiss soldiers.

Charles seems to have had something of a nervous breakdown after Grandson. He began drinking heavily, and made bizarre jokes about his soldiers being loyal to the French king. He did recover enough to start to boast of his military might, and that he still possessed ample resources to beat a foe he still considered contemptible both socially and militarily. But in June, 1476, only a few months after Grandson, Charles was decisively defeated by the Swiss at Morat.

Worse was to follow. Duke Rene II of Lorraine recaptured his capital city of Nancy. If Rene took control of Lorraine, Charles’s lines of communication between Burgundy and his Flemish provinces would be cut. He was now running out of money and manpower. Against all advice, Charles rashly decided to take a gamble and try to recapture Nancy from Rene’s forces in the dead of winter.

It was a foolish move, but Charles was prepared to risk all with one throw of the dice. Sooner or later the Lorrainers and their Swiss allies would come to relieve Nancy and they far outnumbered the rash Duke’s meager forces. Estimates vary, but Charles had no more than around 8,000 men; the Allies at least 18,000. The results were predictable, but this time the course of European history was altered forever. The duke’s generalship was poor, and the Burgundians were not merely defeated, but crushed.

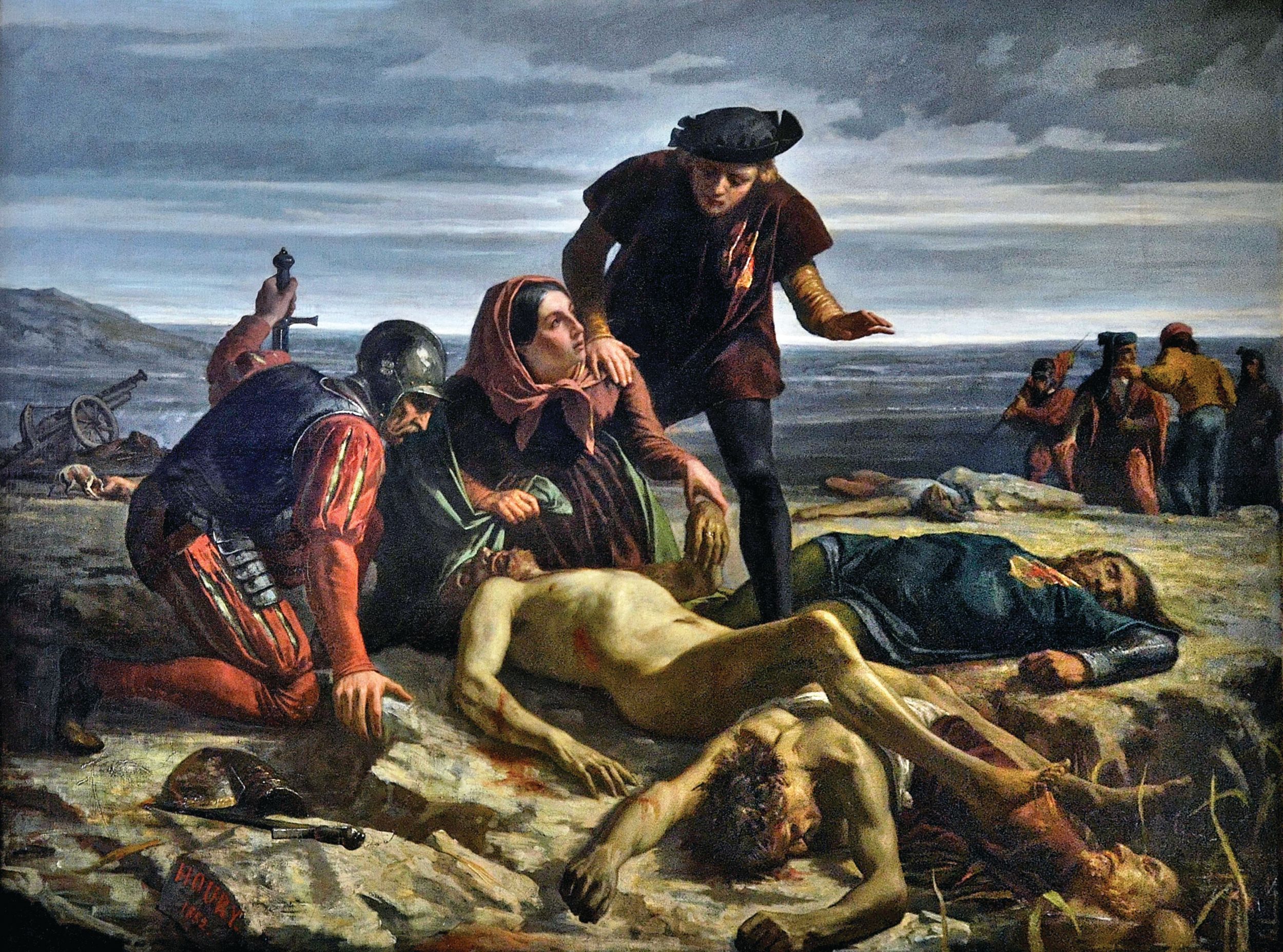

Charles was killed at Nancy, struck down by a halberd that was probably wielded by a Swiss peasant, the kind of man the Duke so despised. His corpse was found a few days later, stripped completely naked, head showing terrible wounds. He was identified by missing teeth and a few old battle scars. His face had been half submerged in icy slush, and part of his features had been eaten away by scavenging wolves.

The dream of a Kingdom of Burgundy, arbiter of western Europe, perished with Charles the Bold. Eventually his Flemish possessions were taken by the Habsburgs, and Burgundy proper was absorbed by France. A mighty prince and his grandiose dreams of glory had died, and European history changed, a process that had begun on the snowy fields of Grandson.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments