By Kevin M. Hymel

“Move out!” shouted Lieutenant Richard “Dick” Winters to the men of Easy Company. It was 6 o’clock on the morning of June 12, 1944, and Easy Company’s paratroopers braced themselves to attack the southern section of Carentan. Lieutenant Harry Welsh dashed forward, leading his 1st Platoon over a small rise and down the slope into the town. His men followed until someone yelled, “Look o-o-o-u-u-u-t!” A German machine gunner in a second-story window perpendicular to the road opened up, firing rounds straight down the street. Bullets popped by the men’s ears and struck the ground, spraying them with dirt and rocks.

Six of the charging paratroopers stayed with Welsh while the rest dove for ditches on either side of the road, hiding from the fire. “Keep moving! Keep moving!” Winters shouted at the men. When they wouldn’t budge he jumped into middle of the road and furiously shouted, “Move out! Move out!” and started cursing. No one moved, some even burrowed into the ground with their hands. The battalion officers, seeing the critical breakdown, shouted at Winters. “Get them moving, Winters! Get them moving!”

Tossing off his gear, Winters dashed to the ditches on the left side of road and, while kicking some of the cowering men, shouted, “Get going!” and spouted more expletives. Then he ran to the right side of the road and continued cajoling the men to join the attack. Enraged and unable to reinforce Welsh’s tiny force, Winters crossed back to the left side, enemy bullets snapping by or ricocheting off the road, and tried again.

Up ahead, Welsh and a handful of his men dueled with the machine gunner, while Welsh tried to figure out what happened to the rest of his platoon.

It was a desperate moment for Winters. His company was divided and frozen. He had led some of these men on a successful attack just six days earlier and nothing like this had happened. If he could not get the rest of his company to join the isolated spearhead, those men would be killed and the attack delayed. Worse, the men bunched up along the road made for a perfect stationary target. If he could not get them moving, the Germans would eventually start picking them off. “You’re gonna die here! Move!” he shouted at them.

Other units were already attacking the vital town. To the north, two companies of the 327th Glider Regiment were pushing south, while on Easy’s left, Fox Company was also attacking. Somehow Winters had to get his men moving.

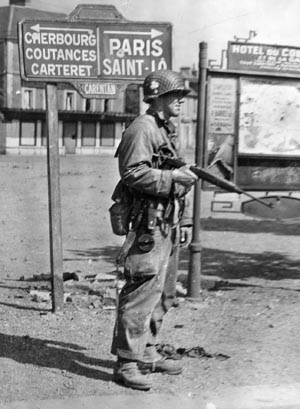

Carentan stood like an island of resistance between the two slowly expanding American D-Day beachheads at Omaha and Utah Beaches in France’s Normandy region. The German grip on the town prevented the two American forces from uniting. With their two main forces divided, the Americans were susceptible to enemy flank attacks while they rapidly built up strength on the shore. The Americans had to take Carentan, not only to unite their forces, but also to access the town’s important crossroads linking the American, British, and Canadian beaches with the Cherbourg Peninsula to the west. Once the Americans held Cherbourg’s harbor, they could start bringing in more supplies for their advancing armies.

Home to some 3,200 French citizens living mostly in old stone three-story row homes above shops, Carentan also possessed a road heading south, away from the Normandy hedgerows, the tree-covered dirt mounds that divided Normandy’s farms into a checkerboard pattern, making them a formidable defense grid for the Germans. An east-west railroad line bisected the town, and the Douve River flows to its south. The Germans used Carentan as an armor repair depot and kept several self-propelled guns there. Man-made swamps surrounded the town, and drainage ditches, streams, and canals confined any attacker to the roads. Hedgerows hemmed the town’s southern approaches.

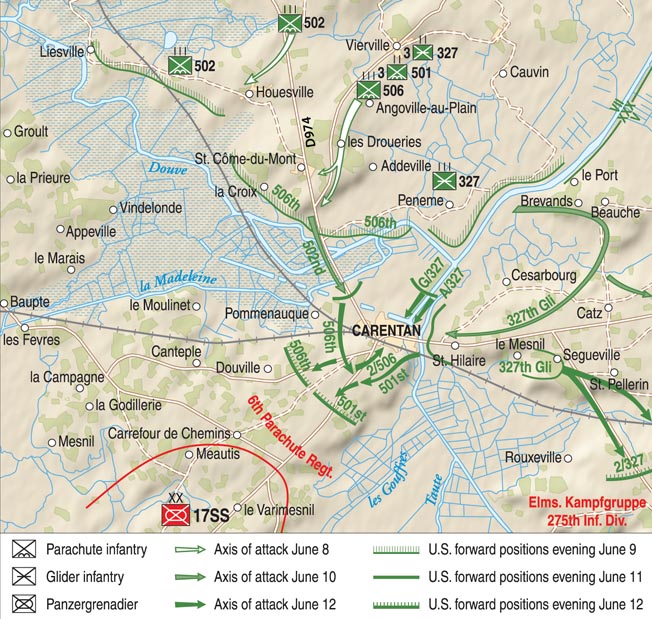

Well before the Normandy landings, Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley had planned for Maj. Gen. Maxwell Taylor’s 101st Airborne Division, the Screaming Eagles, to take Carentan. By June 11, the division had fought continuously since parachuting into Normandy five days earlier on June 6—D-Day, but this would mark the first time the division attacked as a whole. General Taylor planned a three-pronged attack into Carentan for June 12. Two companies of Colonel Joseph “Bud” Harper’s 327th Glider Regiment would attack from the north while two battalions of Colonel Robert Sink’s 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment attacked from south. Sink’s 2nd Battalion, under Lt. Col. Robert Strayer, would attack from the southwest while his 3rd Battalion, commanded by Captain Robert Harwick, attacked from the southeast. Colonel Howard Johnson’s 501st Regiment, on Sink’s right, would also attack north. All three regiments would press forward at dawn.

Lieutenant Winters’ Easy Company would be part of Strayer’s attack. Winters commanded a little more than 100 paratroopers in three platoons: Lieutenant Harry Welsh’s 1st Platoon, Lieutenant Lynn “Buck” Compton’s 2nd Platoon, and Lieutenant Robert Matthews’ 3rd Platoon. Matthews had been killed, so Sergeant Buck Taylor had taken temporary command.

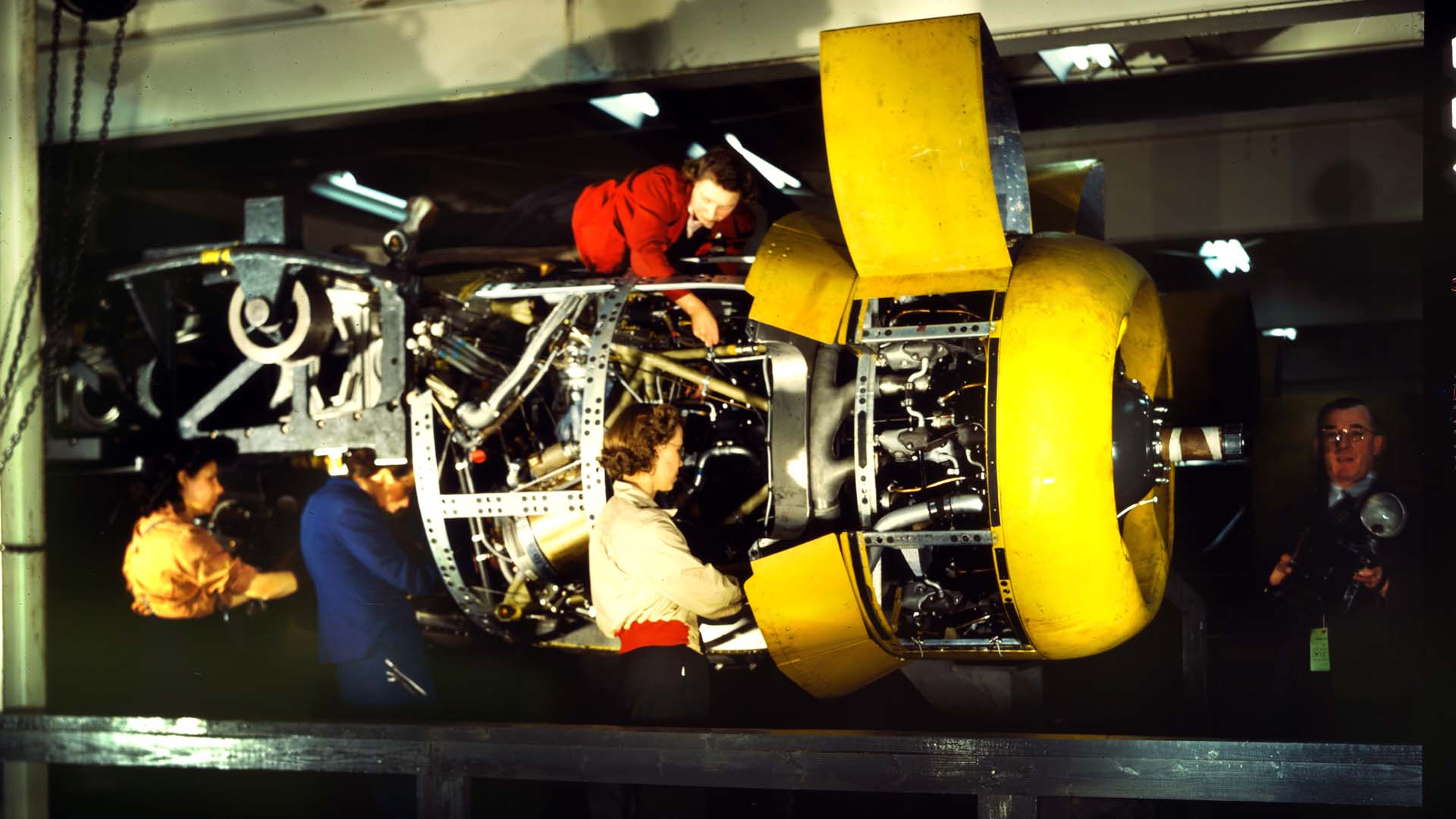

The day before the attack, Gen. Taylor’s paratroopers had already made contact with troops coming up from Omaha Beach. On June 11, at 12:45 pm, Captain Herbert Sobel, who had trained Easy Company from its formation in Toccoa, Georgia, to its training in England, reported that he was “in visual contact with units of the 29th Div[ision].”

The Germans, too, prepared for battle. Major Friedrich von der Heydte, commander of the German 6th Parachute Regiment, had been ordered to defend Carentan to the last man, but he thought otherwise. After American division artillery, tank destroyers, mortars, and naval guns had blasted the town on June 11, and with his men dangerously low on ammunition, he ordered them to evacuate and regroup to the southwest, hoping to counterattack the Americans once support arrived. He left a 150-man rearguard force, consisting mostly of machine gunners and snipers, to occupy key intersections and avenues of approach.

Lieutenant Winters and his company would have to march two miles southwest from Saint-Come-du-Mont with the rest of the battalion to reach their attack positions. It would be no easy trek. They started marching south as the sun set on June 11, staying on the only dry road, D974, passing through flooded fields and over blown bridges where Lt. Col. Robert Cole’s 3rd Battalion, 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment had fought a two-day running battle to clear the roadway of Germans.

Winters’ company followed Captain Marion Grodowski’s Fox Company in the line of march, but in the broken terrain the two units became separated and Easy Company’s lead scouts got lost. A soldier from Fox Company went back, found Easy, and got its men pointed in the correct direction. (Although Winters would later blame the confusion on non-Easy Company officers who had “crapped out” on their night training, the regimental files clearly state that it was Easy Company that became lost.)

Reaching the damaged bridges, the men quietly advanced past the evidence of Cole’s attack. Weapons, destroyed equipment, and German bicycles littered the fields. Dead Germans were stacked like cordwood. When German machine-gun fire cracked in the distance, Sergeant Carwood Lipton, the acting company sergeant, ordered one of his machine gunners to set up and point in that direction. The paratrooper followed orders, but once his weapon was ready, he cocked it. A loud double-clanking sound echoed across the swamps. Lipton looked on in horror, thinking the sound could be heard for a half mile in the still air. “All our attempts at being quiet and surprising the Germans were for nothing,” he thought. Yet, no attack came.

Adding to the company’s difficulties, at a corner where the paratroopers turned right a dead German soldier stood, pointing his rifle at each man as they turned. Some men slowed or froze completely; others ducked and dodged until realizing their mistake.

While that German was dead, an enemy sniper was very much alive and taking shots at the paratroopers, forcing them to dash across the road individually. Private Edward Tipper, weighed down by his bazooka, rockets, and M1 rifle, was sure the snipers would get him, but he made it across unharmed. Sergeant Robert Burr Smith was not so lucky. A bullet or a piece of shrapnel tore into him. “I’m hit! I’m hit!” he called out from a ditch.

The exhausted and battle-experienced paratroopers continued to their destination, discovering another dead German. This one was a paratrooper lying on his back with his arm sticking up. Most of the Easy men tried to step over him, but Sergeant Wayne Sisk stepped squarely on the man’s stomach while shaking his hand. “Sorry buddy,” he told the corpse.

At 2:30 am on June 12, Colonel Sink called his battalion and company commanders together to review the plan of attack. While the officers conferred, their men dropped where they stood and fell asleep. Captain Clarence Hester, the operations officer, gave out the orders from under a raincoat. Sink planned to have Lt. Col. Robert Strayer’s 2nd Battalion attack from the west while Lt. Col. William Turner’s 1st Battalion stayed on Hill 30 outside the town. Sink wanted Winters’ Easy and Grodowski’s Fox Companies to attack side by side, with Easy on the right and Fox on the left. Lieutenant Joe McMillan’s Dog Company would follow the attack. The meeting broke up, and the officers returned to their units.

As Easy Company approached the town in the darkness, Sergeant Lipton, again concerned about a German armored counterattack, ordered his only bazooka man, Private Tipper, to guard a bend in the road. “Tipper,” instructed Lipton, “we’re depending on you. Don’t miss.” Tipper assured him he would not.

Easy Company closed in on its jump-off spot at 5 am, just as two companies of the 327th Glider started their attack from the north. When Germans in a pillbox halted their attack, a gliderman shot a bazooka round into the structure, killing the enemy. The men continued their advance. General Taylor, who accompanied the attack, counted only two German corpses.

Winters’ exhausted men reached their jump-off location at 5:30 am. Their target: a Y intersection defended by the German machine gun overlooking their approach. Winters’ men would have to charge over the crest of the hill and down 100 yards on a sloping road (today’s Rue d’Auvers) straight to the Y intersection (today’s Rue de Périérs). Shallow ditches lined the sides of the road. Once through the intersection, Winters’ men would advance north and link up with the two glider companies.

As the men of Easy hastily prepared to attack, Winters and Grodowski were called back to Sink’s headquarters. As they headed off, an enemy sniper fired two shots close to them. When they reached the headquarters, Sink told the two company commanders that their attack had been pushed back to 6 am.

Winters returned to his company and prepared for the attack. With the clock ticking down, he had no time to reconnoiter the area. He and his men would be going in blind. To add to their troubles, they would have no tank support and little artillery support, although one of the batteries firing into Carentan included a German 105mm gun that some 506th paratroopers had captured.

As the two airborne companies prepared to strike, the Germans struck first. They fired phosphorous shells, burning several Fox men. Then one of the battalion officers, Lieutenant George Lavenson, headed into a field, dropped his pants, and squatted to relieve himself. A German sniper found Lavenson’s buttocks in his crosshairs and fired. Several men had to drag the wounded Lavenson to safety. The Germans knew the Americans were coming.

Winters gathered his platoon leaders. “You’ve got the honors, Harry,” he told Welsh. He would follow Welsh with Compton’s 2nd Platoon and Taylor’s 3rd Platoon. “Get in there fast, all of you,” he told them. “When you hit the [“Y”] intersection, secure it and fan out to the right. Fox Company will handle our left.” With that the men dispersed and made final preparations.

At exactly 6 am Welsh led his charge, and the German machine-gun fire paralyzed the rest of the company. The men ducked, and Winters raged as he crisscrossed the street, yelling, screaming, and kicking his men into action.

As Winters tried to will his men forward, he grew angrier and angrier. The men in the ditches did not rise; they only looked up at their company commander. Winters saw the mix of surprise and fear in their faces. “Come on! Move out! Now!” he shouted with more interspersed curses. His rage shocked them. Winters was considered a mild-mannered officer who never cursed. Few, if any, had ever heard him raise his voice. Now he was cursing at the top of his lungs. It finally did the trick. Sergeant Robert Rader, inspired (or shamed) by his commander’s fearlessness, rose and started forward, and others followed. The attack was on. Easy Company was soon united again.

With the machine gunners focused on the angry lieutenant crossing and recrossing the road, Welsh’s men burst into a house across the street and fired rifle grenades at the gunners until the machine gun stopped. The surviving Germans withdrew, opening the southern entrance to Carentan. The intense fire at the Y intersection may have helped Grodowski’s Fox Company. His attack got off 20 minutes late but made good progress through the town with the Germans so focused on Winters’ men.

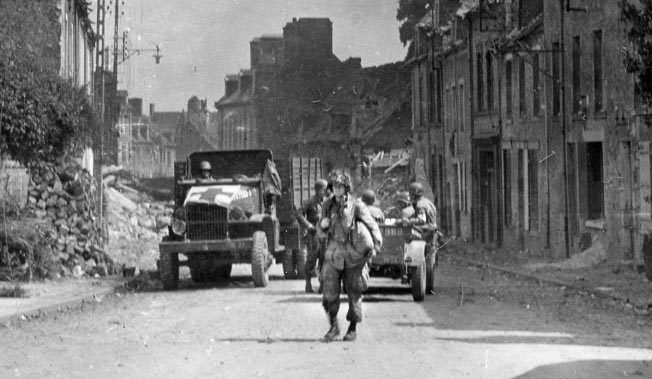

As the Easy men advanced down the narrow streets, they became intermixed with Fox and Dog Companies. The Americans began breaking down doors and searching inside, cursing as they went. Stone rubble filled the sidewalks and streets. Whenever the Germans opened fire, the paratroopers ducked into the doorways and alleys before resuming their charge. The paratroopers fired at any windows they saw, whether they spotted Germans in them or not. They tossed hand grenades through windows and doors and then charged into the homes and shops looking for Germans, sometimes finding civilians in the basements.

Sergeants Lipton and Taylor worked together clearing buildings. At one with an outside staircase, Lipton told Taylor he would head up the stairs and wait for Taylor to throw a hand grenade through the window before he entered. Lipton raced up the stairs, and when he heard the grenade explode, he burst through the door, rifle pointed and ready to fire. Unfortunately, he could not see anything. The room was filled with blinding dust and smoke. It was, however, empty.

The southern section of the town was surprisingly empty. Once past the machine-gun nest, many of the follow-up men did not fire their weapons; they merely walked. Lieutenant Compton described Carentan as a shambles. “Crumbled buildings, dead Germans lying all over. It was already slaughter alley,” he wrote. He calculated that he saw an enemy dead body about every 10 feet or less, most with missing limbs or heads. Blood was everywhere. “Without a doubt,” he said, “it looked like the town didn’t belong to the Germans anymore.”

Private Clancy Lyall reached Rue Holgate, which ended at the railroad, the phase line for the southern attack. When he saw Germans firing a machine gun down the road at his fellow paratroopers, he dropped his gear, grabbed a hand grenade, and bolted around a corner where he expected to find a machine-gun nest in a window. Instead, he ran straight into an enemy bayonet. It was attached to a rifle held by a surprised German. The bayonet penetrated an eighth of an inch above Lyall’s stomach. Both men stood in shock, until Lyall fired his rile. The German fell back, pulling out the bayonet in the process, and then shot Lyall in the leg. Lyall dragged himself to a partially destroyed stone shop, where he injected himself with morphine and hollered for a medic. Eugene Roe reached him and administered more morphine.

Winters crossed the tracks and reached another intersection in the heart of Carentan. He ordered the rest of Welsh’s 1st Platoon to turn left and Compton’s 2nd Platoon to turn right. Sergeant Talbert and some of the men of Taylor’s 3rd Platoon charged past Winters. “Which way when we hit the intersection?” Talbert asked the company commander. “Turn right,” Winters responded. Privates Tipper and Joseph Liebgott followed Talbert to the right.

Easy men continued heading north until they reached Carentan’s main square, dominated by the statue of a winged angel holding an olive branch, honoring the town’s World War I dead. The trees in the square had been shattered by shellfire. Talbert reached the square and spotted a German’s shoulder protruding from behind a tree. He took aim and fired. The German spun to the ground, writhing in pain. When he reached for his weapon, Talbert shot him again, killing him. “He looked so young,” Talbert later said.

How Company from Captain Harwick’s 3rd Battalion joined the Easy and Fox men and helped them surround a German sniper hiding in a tree. The German surrendered and had to run down the street while a gauntlet of paratroopers kicked, smacked, and jeered him. Winters was having none of it. “Secure this intersection,” he called out. “Clear those buildings to the right!”

Paratroopers from both Easy and Fox Companies continued heading north until machine-gun fire swept the center of the street. A Fox Company paratrooper, thinking it sounded familiar, tossed an orange smoke grenade out in the open. The firing stopped, and glidermen from the 327th approached and greeted their brothers pushing north. The link had been made, but there were still Germans fighting in the town. They had to be cleared out.

Near the town’s center, Private Darrell “Shifty” Powers ran past a chicken coop next to a building and noticed a burst of fire coming from a warehouse’s second story. He pushed his shoulder into the building’s corner, stopping his momentum. Then he dropped to one knee and poked his head around the corner to range the target and ducked back. “The shot was mine,” Powers later recalled. Holding his breath, he raised his rifle, spun around the corner, fired, and ducked behind the corner again. He made the shot, but before he could celebrate another machine gun opened up from a different window, spraying the street in front of him with brick shards. He froze. Men rushed by him calling, “We gotta take that warehouse!” When they noticed Powers standing still, one yelled to him, “Shifty! Shifty! You okay?” Powers shook it off and followed them.

Technical Sergeant Ralph Stafford entered a house and heard voices in the basement. He quietly descended the stairs to find a German looking out a small window onto the street. The German spun around, but Stafford fired first. The German dropped to the ground, and Stafford headed back up the stairs without checking to see if he was dead.

As the men advanced through the city, enemy small-arms fire began to die down, but mortar and artillery fire increased. The first explosion rocked the center of town. “Mortars!” yelled Winters. “Get down!” Before Corporal Dewitt Lowrey could react, shrapnel smacked into his head, and he collapsed. Other Easy men ducked for cover.

Private Tipper was exiting a row home when the mortars started exploding. He and Private Liebgott had been working together. Tipper had thrown a grenade through the home’s window while Liebgott kicked in the door. They both entered the house, but Liebgott soon departed while Tipper checked out the second floor and backyard, finding nothing but an outhouse-looking shed. He shouted a warning and fired a few rounds through it before exiting out the front door. He had just stepped out and was waving to Liebgott when a mortar exploded in front of him, throwing him back into the house and tearing off his helmet. Despite feeling like a train had hit him in the chest, he felt no pain. Everything went silent. Somehow, he was still standing with rifle in hand. Thinking that a German hiding in the shed had tossed a grenade at him, Tipper, bleeding and wounded, turned around and raised his rifle. Leibgott came up behind him, walked him outside, and helped him to the ground. Leibgott shouted for a medic. While he reassured Tipper he would be alright, Tipper reached up and touched his head, finding it mushy like a pumpkin and twice its usual size. His right eye was missing.

Mortars continued to explode around them. Lieutenant Welsh rushed over. “You’re going to make it,” he told Tipper. “We’ll get you to an aid station.” Tipper tried to tell him he could walk as Welsh injected him with morphine. While a medic bandaged Tipper’s head, Sergeant Lipton hurried over and told him he would be well taken care of. Welsh and Liebgott then helped carry him down the street to an aid station. Tipper could feel the broken bones in his legs grinding together as they walked. With enemy artillery continuing to rain down, they had to duck behind walls several times as bullets and shrapnel zinged above their heads. Once in the aid station on the southern side of the railroad tracks, a Fox Company paratrooper entered, hoping to use the building’s domed second floor to fire his machine gun at the remaining Germans. The doctors in the aid station talked him out of it, reasoning that they were a noncombat facility.

Sergeant Lipton, after telling Tipper he would be alright, continued forward until he noticed an explosion against a building near an intersection where a group of Easy men stood. Lipton, kitty-corner from them, hollered for them to get moving, but before he could finish a mortar round detonated a few feet in front of him, tossing him backward. Shrapnel tore into his face, wrist, leg, and crotch. The blast tore his rifle from his hand, and it clattered loudly on the sidewalk. He landed in the street, then shook his head to regain his senses and checked his injuries. As he felt a hole in his cheek with his left hand, his right hand spurted blood.

Floyd Talbert raced to him and put a tourniquet on his hand. Lipton then dropped his left hand to his crotch, and it came up bloody. “Talbert, I may be hit bad,” he told him. Talbert cut away Lipton’s pants with a knife and reported, “You’re okay,” to Lipton’s great relief. Talbert then threw his company leader over his shoulder and took him back to the medical station set up by the railroad tracks. Lipton asked Talbert to take over the platoon.

While Talbert worked on Lipton, the enemy mortar rounds ceased. Paratroopers ran past the two men, searching houses and ducking behind walls to fire on escaping Germans. One paratrooper, a pale-faced Private Albert Blithe, crumpled against a wall, his eyes staring at nothing. Private Powers thought he looked like a man who “wasn’t in his own body anymore.” Blithe had suddenly become blind. Some men helped him to the aid station.

Meanwhile, Liebgott departed the aid station and joined Sergeant Walter Hendrix and another man looking for snipers, hoping to bring back a prisoner. As they advanced under fire, the man following Hendrix crawled over a mine that exploded, killing him. Hendrix and Liebgott soon spotted two German snipers and killed one. The other surrendered. Liebgott, possibly angry over the loss of Tipper, wanted to kill the German, but Hendrix refused. “I was never trigger happy,” Hendrix later explained.

As the firing died down, paratroopers from Lt. Col. Julian Ewell’s 3rd Battalion, 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment entered Carentan. His men had taken Hill 30 south of the town and then made their approach.

The town’s dwindling number of Germans caused headaches for the paratroopers. When a group of surrounded Germans refused to surrender their building, the men fired a bazooka round into the door. A German stumbled out, and a pistol-wielding paratrooper shot him. Elsewhere, a German sniper tried to hit Private Powers and another soldier by ricocheting shots at their location, to the two men’s amusement. They had broken into a wine shop and were sampling their findings as the German fired vainly. “We kind of enjoyed that,” Powers later said.

As Sergeant Don Malarkey advanced through the town, he heard an odd sound above the moans of the wounded and the occasional rifle fire. A calm, stoic voice kept repeating, “Hail Mary, mother of Jesus, full of grace.” It was Father John Maloney, the regimental chaplain, walking down the center of the street holding a cross and administering last rites to the dying as bullets ricocheted around him. “Never seen anything like it,” Malarkey wrote later.

Lieutenant Winters and Sergeant Denver “Bull” Randleman reached the town church and turned right, down a street lined with houses. Randleman spotted Private Richard Bray and ordered him to check behind the houses for Germans. Once Winters and Randleman reached the edge of town, they went into the last house, climbed to the second floor, and watched escaping Germans running across a field. Randleman fired several rifle grenades at them. As the two men left the house, Randleman asked a paratrooper about Bray, and the paratrooper said Bray had been hit. “Is nobody going to get him?” Randleman asked. The paratroopers around him said no.

Randleman went behind the houses and found Bray, who had been hit in the leg. He gathered the man up, put him over his shoulder, and ran him to the aid station, where he cut a hole in Bray’s pants with a knife and poured sulfa powder on his wound. He then handed Bray his morphine syrette and told him to stick himself if the pain became unbearable while waiting for a medic.

While Randleman worked on Bray, Winters headed back to the center of town to check on the company’s ammunition supply. As he walked down a sidewalk, Lt. Col. Strayer called to him, “Lieutenant Winters, is it safe to cross?” The battalion commander and his staff were crouching against a wall across the street. “Yes, sir.” Winter’s replied and stepped into the street to demonstrate, a little irritated after fighting exposed for the last few hours. Strayer and his staff hurried across.

Winters was standing alone in the street when a bullet slammed into his left shin. He gasped in pain, hobbled to the side of the road, and blurted out “Goddammit!” He knew he had exposed himself needlessly. Lieutenant Welsh hurried over and helped him into a sitting position before removing Winters’ boot. “It’s not that deep,” Welsh explained. “Maybe I can get it.” He started probing the wound with his knife until Winters told him to stop. “Harry, you’re all thumbs,” said Winters as he winced in pain. “Just help me to the aid station.”

Once there, Lieutenant (Dr.) Jackson Neavles pulled the bullet out of Winters’ shin. Winters noticed the blind Private Blithe as he prepared to leave. He asked him what was wrong, and Blithe explained that everything had gone dark. Winters patted him on the shoulder, told him he would be sent back to England, and said, “Hang tough.” As Winters left, Blithe called out, “I can see. It’s okay. I can see. I think I’ll be all right.” Winters returned and looked into Blithe’s eyes. He agreed that he could see but insisted that he go back to England. Blithe pleaded to be sent back to his unit, and Winters finally relented.

Before noon on June 12, 1944, Carentan had been substantially cleared of the enemy, but there was one thing the Screaming Eagles needed to do: celebrate. Like Private Powers, the men discovered stocks of wine and cognac in the basements around town. They cheered their success and drank heartily. Some lunched on liberated bread. General Taylor and Colonel Sink were not to be left out of the festivities. They used the liberated liquid to toast their victory. The American front was now completely connected.

While the Germans did not put up a stout defense, they did take a toll on Winters’ men. Easy Company suffered eight wounded (including one case of temporary blindness) from both artillery and German rifle fire. Still, Winters had proven his leadership again to his men, first by prying them off the ground during the initial attack, then by coordinating the battle under fire, and finally helping restore sight to a blind man, an impressive act not many officers could attest.

Despite the jump-off jitters, the men of Easy Company performed admirably. Although exhausted and lacking artillery and armor support (and with little, if any, house-to-house combat training), the men rushed the town and efficiently searched the buildings. While they clearly had a numerical advantage over the Germans, they did not waste it or commit any mistakes of judgment or rashness. They were becoming veterans of the battlefield.

The victory celebrations in the heart of Carentan did not last long. The Americans headed out to take more objectives six miles to the west and southwest, but a German counterattack stopped them approximately 1,000 yards outside of Carentan. Von der Heydte had been reinforced by the 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division and was determined to retake Carentan. The paratroopers set up defensive positions. In less than 24 hours the Germans would attack. Lieutenant Winters and the men of Easy Company would soon be tested again in battle.

Kevin M. Hymel is a historian for the U.S. Air Force Medical Service History Office at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas, and author of Patton’s Photographs: War as He Saw It. He is also a tour guide for Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours and leads tours to Carentan and other locations where Easy Company fought.