By Matthew J. Benedetti

Two decades after the carnage of the Great War, the world was again plunged into the cauldron of armed conflict.

During a six-year span (1939-1945), another catastrophic war shook humanity to its foundation, and the staggering losses suffered in World War II are difficult to conceptualize. The appalling casualties sustained by all of the combatants during this conflict eclipsed 55-60 million dead by conservative estimates (the Soviet Union alone suffered approximately 20 million dead).

Distinct in myriad ways beyond the astronomical body count, few would find respite from the maelstrom of death and misery in this truly global war.

No corner of the world was spared. Even the remote Pacific islands of Tarawa and Guadalcanal experienced intensive fighting between U.S. and Imperial Japanese forces. Previously uninhabited rain forests of Burma would see troops of the British and Japanese Empires fight starvation as well as one another for years. Both forces would suffer more casualties to the common enemy of malaria and other tropical diseases than actual combat in this theater.

Australian soldiers watched in awe as bombs from supporting American bombers failed to register little more than muted thumps under the triple-canopied jungles of New Guinea.

Inhabitants of disparate locations like Norway, Tunisia, Albania, and Hawaii witnessed war in ways they could never have imagined.

Even Attu and Kiska, the sparsely populated Aleutian Islands off the Alaskan coast, have cemeteries honoring fallen U.S., Canadian, and Japanese serviceman.

It is true, of course, that several campaigns could reasonably be argued to have been the most important engagements of World War II.

Without question, the naval battle of Midway between the U.S. and Japanese Navies irrevocably altered the course of the Pacific War.

In June 1942, Japanese Fleet Commander Admiral Yamamoto was poised to immobilize the remaining U.S. aircraft carriers that had escaped the Pearl Harbor attack six months earlier. Seizing the initiative, Yamamoto hoped to follow traditional Japanese naval doctrine by drawing his quarry from nearby Hawaii into a decisive Japanese victory. Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander of Task Force 17, turned the tables on Yamamoto, resulting in a decisive victory for the U.S.

Due to the breaking of the Japanese naval code by the Office of Naval Intelligence at Pearl Harbor, U.S. Pacific Fleet Commander Admiral Nimitz was well positioned to preempt the Japanese attack. The Combined Japanese Fleet lost four carriers—the entire strength of the task force—Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiryu, with 322 aircraft and over 5,000 sailors. The heavy cruiser Mikuma was also sunk. American losses included 147 aircraft and more than 300 sailors.

The Battle of Midway was decisive. The outcome rendered Japan incapable of advancing further east for the remainder of the war. Undoubtedly, Midway was a critical victory, allowing the United States to take the offensive.

Stalingrad is, by any measure, the pivotal battle on the Eastern Front. The Soviet Red Army and German Wehrmacht engaged in a pitiless fight of attrition in this industrial city named in honor of Soviet leader Marshal Josef Stalin. The city’s name fueled a personal vendetta within Adolf Hitler, who devoted the majority of Army Group South and significant elements of Army Group Centre to destroy the vital manufacturing center along the banks of the Volga River.

The vaunted German Sixth Army, commanded by Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus, fought tenaciously for this symbolic rather than strategic objective. Faced with operating in appalling conditions against an unyielding enemy, German troops managed to occupy 90 percent of Stalingrad in what would ultimately prove to be a pyrrhic victory.

Anticipating a swift victory in the east, optimistic OKW planners had failed to equip “Ostfront” troops with winter clothing and other essential materials. Indeed, premature reports of German victory belied the ongoing close-quarter fighting taking place among starving soldiers amid the snow, rats and rubble.

When Red Army General Georgi Zhukov launched a massive Soviet counteroffensive, he mirrored the tactics of his German adversary. During the June 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union, German armies successfully isolated entire Red Armies by encircling units from their logistical base. These Kesselschlact, or “cauldron battles,” were replicated throughout the German offensive, resulting in staggering Russian casualties. Now, by smashing the Hungarian, Italian, Rumanian, and Bulgarian Axis armies in Operation Uranus in a massive pincer movement, Zhukov severed Paulus’ flank while isolating the Sixth Army in Stalingrad.

The Wehrmacht’s defeat at Stalingrad inexorably shifted the balance of power in the Great Patriotic War in favor of the Red Army.

Operation Overlord, or “D-Day,” is universally recognized even by individuals unfamiliar with World War II. It’s been chronicled in popular culture by the brilliant Cornelius Ryan book and in Hollywood movies such as The Longest Day as well as the epochal Steven Spielberg film Saving Private Ryan. To many historians, the scaling of Point De Hoc by elements of the 2nd and 5th Ranger Battalions is considered to be the gold standard of military courage and tactical skill. A reference to the terrible sacrifices made by soldiers on Omaha, Juno and Gold Beaches on June 6, 1944, never fails to summon pride in most Americans.

Even the remarkable deception employed by the Allies to divert mechanized SS divisions to the Pas de Calais, away from Normandy, is viewed as incredible feat of tactical daring. Many could convincingly argue that if this largest amphibious invasion in military history had failed, then subsequent Allied invasion plans would certainly have been modified and perhaps delayed indefinitely.

A costly assault on the Gustav Line, running the width of Italy, may have been revisited. German positions were well entrenched, and progress was measured in yards by Allied soldiers. Unlike the wide expanse of French fields conducive to air power and mechanized units, the Italian Alps favored defense, and the human toll was heavy.

The success of the Normandy invasion, although costly, had achieved the desired outcome. Within a year, the war in Europe would be over. Field Marshal Gerd von Runstedt understood, as did most senior German military leaders, that breaching the Atlantic Wall would ultimately lead to capitulation. Certainly D-Day was the most important land battle of the Western European campaign.

It is beyond debate that Midway turned the tide of war in the Pacific, that Stalingrad inexorably shifted the balance of power in the east, and that D-Day opened the second front and tightened the vise on Hitler and his Third Reich.

However, these momentous engagements would have never taken place if not for the Battle of Britain in 1940.

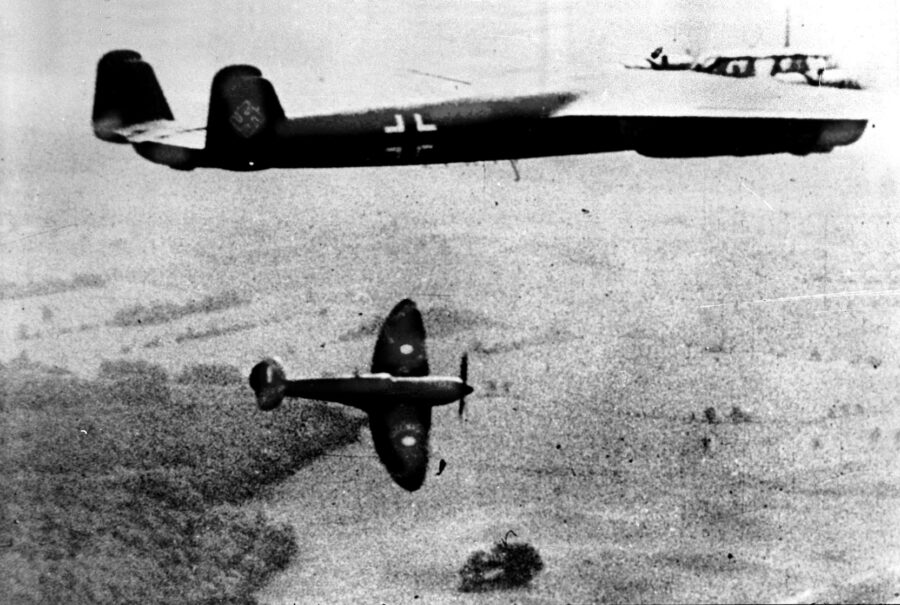

In the summer of 1940, the British Royal Air Force and German Luftwaffe engaged in the largest aerial battle in history fought exclusively by two opposing air forces. Of course, the British defied the odds and prevailed in a conflict that has been a source of English pride for decades. However, if the RAF, led by the intrepid Spitfire and Hurricane pilots, had not prevailed, the outcome of the war would likely have shifted in favor of the Axis.

After swiftly defeating France and the rest of Europe, the German Blitzkrieg showed no signs of abating, and, notwithstanding Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s spirited rallying of the populace, many harbored doubts as to whether the beleaguered British Army and Royal Air Force could withstand the expected German seaborne assault (Operation Sea Lion).

The Luftwaffe had a significant advantage in aircraft and had pioneered advanced tactical concepts. Its coordination of air strikes on enemy formations via radio communications was unprecedented and devastatingly effective in both the Polish and French campaigns. A Luftwaffe tactical control officer would be embedded with forward army units and relay the positions of enemy units to airborne Stuka dive bombers, who would promptly attack with their signature wailing Jericho sirens. The stunned enemy would often surrender and, more importantly, morale would be sharply corroded.

The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) had been forced to abandon the majority of their artillery and vehicles on the beaches of Dunkirk earlier in the spring. Few felt confident that the underequipped British Tommies could thwart a coordinated German attack.

The stage appeared set for another German triumph.

Due to extraordinary courage demonstrated by the RAF and an even more impressive deployment of previously unknown technologies like the Chain Home Radar defenses, this outcome was avoided. If the British had lost or struck a Vichy-like deal—which was suggested by many in the aristocracy—the fate of Europe and the world would have been entirely altered. The U.S. likely would have had neither the political will nor the staging area in the UK to contest Axis supremacy in Europe. Undoubtedly, German power would have grown with the additional resources, and a stalemate may have been the least terrible option.

And the RAF victory in the Battle of Britain exposed vulnerabilities, however small, in the previously unbeatable German war machine.

Here are key components of the battle as seen from the political, strategic/tactical, and possible-outcome perspectives.

Political

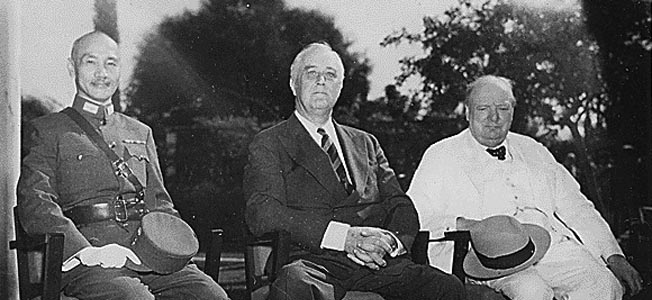

Prime Minister Winston Churchill is one of the most recognized and lauded figures of the twentieth century. It is with good reason that this cherubic, middle-aged and somewhat eccentric figure is widely considered the example of stalwart leadership.

Blessed with a stubborn will, a gift for oration, and keen judgment, Churchill charted the course for victory in the Battle of Britain and the subsequent hard-earned victories to follow.

In retrospect, it seems natural for the British Parliament to have selected such a pugnacious and gifted prime minister. However, it was luck as much as savvy political acumen that prompted Churchill to remark that he felt as if he were “walking with destiny.” In many ways, he was a compromise candidate, and the post had been offered to Lord Halifax, a well-known appeaser, who had demurred. The previous prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, practically groveled to Herr Hitler during negotiations in 1938 and held the misguided belief that he could reason with the Nazi dictator.

In contrast to the supplicant Chamberlain, known in some circles as ‘the Undertaker’ due to his dour demeanor, Churchill had long been a vocal opponent of Hitler, accurately assessing his vile ambitions even while in the political wilderness. Much can be learned about the mood of England during this period. In many ways, the fate of the West was decided in a smoky room within the Halls of Parliament in May 1940. Seven members of the War Cabinet had convened to discuss the next course of action.

Churchill chaired the meeting, surrounded by political opponents. Among them was Neville Chamberlain, the ex-prime minister he had recently supplanted as prime minister. Lord Halifax, the foreign secretary, and Archibald Sinclair, the leader of the Liberal Party that Churchill had recently cashiered, were the primary voices.

The question to be answered on that day was straightforward. Should Britain fight? Was it reasonable for young British troops to die in a war that showed every sign of being lost? Or should the British broker an arrangement that might potentially save hundreds of thousands of lives?

In fairness, there was little room for optimism given the grim circumstances. Driven from the continent, the BEF had limped back to the UK without its equipment or confidence. France, boasting a large and modern continental army, had capitulated to the blitzing German Army in a shocking six weeks. Norway, Denmark, and the Low Countries, along with Poland and Czechoslovakia, were also firmly under the Nazi heel.

As well, the Battle of the Somme and the horror of the Great War 20 years earlier were burned into the collective English memory. World War I had proven to be a hollow victory, leaving hundreds of thousands of a generation dead as well as hundreds of thousands of wounded veterans and orphans in its wake.

Wary of further continental entanglements, the English public offered Chamberlain the commensurate political cover to negotiate away sovereign central European countries (Austria and Czechoslovakia) in a desperate hope of appeasing Berlin. Naturally, Chamberlain’s detached stance only emboldened Hitler and other bullies everywhere, encouraging further aggression.

As well, many among the English upper classes were primarily interested in preserving their collective wealth and property. Though unsympathetic toward the ascendant Nazis, many elites as well as Whitehall ministers feared the prospect of losing a war (and their holdings) in a futile struggle. Why not negotiate now and avoid a costly war of attrition?

Several respectable Britons publicly preferred fascism to communism and the Bolshevik concept of “wealth redistribution.” Lady Nelly Cecil noted that nearly all of her relatives were “tender to the Nazis.” Former Prime Minister and hero of the Great War David Lloyd George declared that Hitler was a “born leader” and compared him to George Washington.

King Edward Vlll’s dubious Nazi ties and his widely publicized accompanied visits to Germany with his wife Wallis Simpson not only raised eyebrows but also reflected a small but strong pro-Axis sentiment within elite circles of the United Kingdom. The brutish Nazis at least respected property rights, unlike the commissars in Moscow, they argued.

The Italian Embassy had signaled interest in establishing a backchannel between London and Rome. It was Halifax who introduced the idea of negotiating with Italy.

Churchill, to his enduring credit, dismissed the overture in front of the larger cabinet, which had convened later in the day. During this gathering, Churchill summoned his trademark gift for oratory and his uncanny ability to stir the emotions of men.

By appealing to their better angels, he convincingly argued that accepting the offer to negotiate even surreptitiously would be perceived as a step to surrender. After delivering a compelling address peppered with Shakespearean references, he managed to persuade the larger cabinet to his view. While the positions of Halifax and Chamberlain mirrored the anxious mood of the British people, Churchill recognized a false flag when he saw one.

The outright rejection of the offer to negotiate summoned a dormant ministerial vigor within the cabinet while simultaneously evoking a latent pugnacity in Britons long inured to military reversals.

The escape at Dunkirk allowed over 300,000 BEF and French troops to serve again but also sparked debate. Why did the Germans stop? Were the fatigued soldiers recovering from the copious amounts of the stimulant Pervutin? Did Reichsmarschal Hermann Göring really demand the glory and convince Hitler to attack from the air? Was Hitler leaving open the possibility of détente with the British, whom he viewed as a Teutonic equal race?

That mystery remains.

Though an inspirational wartime leader, Churchill was not without faults. Moody, capricious and sometimes drunk, he did possess, however, the stalwart character to stand his ground when in the right. His adroit political maneuvering and outward confidence buoyed an apprehensive populace.

Strategic/Tactical

Operation Sea Lion, the German codename of the plan to invade the United Kingdom, was a multifaceted assault that would have deployed all available aircraft, landing craft, airborne troops and personnel.

In the spring of 1940, planning meetings were taking place but stalled due to a number of factors. A historically continental power, the German leadership as well as Hitler himself were apprehensive regarding a seaborne invasion, especially on such a broad scale. Norway was one thing, but Great Britain another matter altogether.

Admiral Erich Raeder, the Kriegsmarine Commander in Chief, could not reasonably provide adequate protection for a sizeable landing force. Though the British Army was battered, the Royal Navy still boasted the strongest fleet in the world, and the RAF was small but proficient. Joint military planners concluded that the prospects of a successful amphibious invasion of England were limited and feasible only if the Luftwaffe could secure total control of the air over the battle space.

Unphased by this sobering assessment, Göring assured Hitler that he could do so within weeks. Göring is often portrayed as a bit of a dolt. This characterization is unfair. The rotund Luftwaffe chief was often the subject of enemy propaganda and was arguably the most recognized Nazi leader other than Hitler. Though vain and arrogant, he was also a visionary and master organizer. Göring amassed breathtaking power and wealth in an arena full of cunning men.

The consummate diplomat, he charmed both Lord Halifax and Chamberlain on their visits to Germany in 1938. A World War I fighter ace and recipient of the Pour Le Merite, he covertly engineered the development of the most innovative and modern air force in the world, the Luftwaffe. The Messerschmitt 109 fighter and Junkers dive bomber revolutionized the rules of aerial warfare.

In early engagements, his Luftwaffe overwhelmed opponents with dash and elan. From the Legion Condor in the Spanish Civil War to the routing of Armee de l’Air and the RAF in the Battle of France, Göring could justifiably point to his air arm with pride.

He astutely expended his subsequent political capital to garner additional resources for his beloved Luftwaffe. While the Heer (Army) and Kriegsmarine (Navy) competed for the Führer’s influence, Göring, secure in his lofty perch, enjoyed casual hunting excursions at Carinhall, his sprawling country estate.

But, despite the impressive string of victories, Göring made two critical mistakes in the air battle with Britain. Both errors pertained to planning: one strategic and the other operational.

Delighted with the success of the dive bomber, Göring failed to plan and invest in a heavy strategic bomber that could travel a great distance and damage large targets.

The Stuka, while extremely lethal in supporting ground troops, was plainly vulnerable in contested skies. The Me 110 Zestorer (Destroyer) proved to be an unwieldy hybrid. Not fast or maneuverable enough to be a fighter, the 110 also lacked the torque to be a reliable dive bomber. Spitfire and Hurricane pilots would enhance their kill ratios against the Stukas and Destroyers during the battle over southeast England and the Channel.

Göring’s growing hubris and unwillingness to accept unpleasant facts regarding the air campaign further eroded prospects for a German victory. Confronted with reports of heavy Luftwaffe losses, he deflected blame for the mounting setbacks by pointing to a lack of resolve on the part of his airmen rather than flawed strategy or leadership.

By adamantly refusing to consider the possibility that the RAF had employed a sophisticated warning system, Göring sacrificed countless Luftwaffe airmen by ignoring sound advice. The failure to target coastal radar stations proved to be a fatal error. This omission allowed RAF interceptors to scramble squadrons from the multiple sector stations along the coast. This intelligence provided fighter pilots with an invaluable weapon: timely knowledge of the location and number of approaching enemy aircraft

No army, navy, or air force is ever fully prepared for war. Too many variables and contingencies can alter planning and doctrine. RAF Fighter Command in 1940, however, had achieved as sound a readiness posture as any unit in the modern era.

A brilliant visionary, Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, served as the Commander-in-Chief of RAF Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain, and his contributions are indelibly etched into aerial warfare doctrine.

During the 1930s, in his capacity as the Air Member for Supply and Research at the Air Ministry, he oversaw two vital developments in the preparation for war. The first was the development of fast fighter aircraft, the Supermarine Spitfire and the Hawker Hurricane. The second was to provide funding for the first experimental RADAR (then known as RDF) stations on the coast. Both investments in technological development were integral to victory in the Battle of Britain.

Dowding created the world’s first integrated system of air defense, which became known as the “Dowding System.” The Chain Home High and Low radar network provided the RAF with accurate, timely intelligence relative to German objectives and force structure. This coordinated intelligence system enabled analysts to detect German aircraft up to 120 miles away. After crossing the coast, the aircraft’s height and course were confirmed by the Observer Corps and relayed to sector stations.

Information from these coastal radar stations was processed in the squadron filter rooms and sent to Bentley Priory, RAF headquarters. Orders were issued to the four regional Group Headquarters and their respective Sector Headquarters.

A complex web of telephone communications operated by the General Post Office served all elements of the Dowding System.

A headstrong leader, Dowding often clashed with Churchill. He strongly advocated keeping fighters in England rather than deploying squadrons in support of an indifferent French defensive effort—a view validated by subsequent events.

Even with this distinct intelligence advantage, the task of defeating the Luftwaffe was daunting. The Germans enjoyed a significant numerical advantage of 2,600 operational planes to just 600 at the outset for RAF Fighter Command.

The Battle of Britain raged over the skies of England from July 10 until October 31, 1940. German air units traveled from bases in France, Holland, and Norway. Flying these great distances took a toll on pilots, and many succumbed to fatigue, causing appalling casualties. As well, each pilot became keenly aware of his fuel gauge due to the fear of running out of petrol over the Channel. German aircraft needed to be precise, as they could only fly approximately 20 minutes over land before returning to base. To add to the frustration, Me 109s were required to escort not only the Stuka dive bombers but the Zestorer 110s, limiting their tactical flexibility.

Though pushed to its operational limit, the RAF inflicted enough damage on the Luftwaffe to at least postpone Operation Sea Lion.

The British suffered 1,542 aircrew killed, 422 aircrew wounded, and 1,744 aircraft destroyed. German losses were 2,585 aircrew killed or missing, 925 captured, 735 wounded, and 1,977 aircraft destroyed.

The Battle of Britain represented the first setback of the previously invincible Nazi juggernaut. Directive 17, the seaborne invasion of England, was never attempted, though aerial bombardment, including the introduction of the horrific V-1 and V-2 rockets, continued throughout the war.

Possible Outcomes

If Lord Halifax or another minister other than Churchill had become prime minister, what would have transpired? Certainly, the British response would have looked much different. In addition, popular opinion in the U.S. was overwhelmingly opposed to involvement in the latest European war. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s fireside chats and behind the scenes machinations notwithstanding, could Americans again be convinced that a European conflict was in the national interest?

Though a popular president, the wily Democrat was seeking an unprecedented third term in 1940, and election year realpolitik would have required a cautious platform relative to international affairs.

Indeed, Roosevelt’s ethnic, working-class voting base was largely comprised of Italian, German, and Irish surnames. It stands to reason that the first two groups would balk at fighting their kin, and the latter would celebrate an English defeat. (Despite tremendous diplomatic pressure from both London and Washington, Ireland remained neutral during World War II.)

Pragmatic realpolitik of another kind would compel FDR or another president to tolerate such a strong European power: the moribund state of the U.S. military at the time.

On December 11, 1941, four days after the Pearl Harbor attack, Germany declared war on the U.S.—a curious decision, given that the once-mighty Wehrmacht was mired in the vastness of Soviet Russia and already gravely overextended. Many historians believe that Hitler hoped his declaration of war on the U.S. would encourage his Axis ally Japan to follow suit against the Soviet Union in the Far East, thus relieving pressure on his beleaguered German armies on the eastern front.

Ultimately, Japan’s mounting military commitments throughout Asia made such a course of action imprudent.

Would Hitler have aggravated tensions with the U.S. if Great Britain had capitulated and come to terms? Would Japan have attacked Pearl Harbor to expand the “East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” if European hostilities had ended? Given the growing bellicosity between Washington and Tokyo over a host of seemingly intractable issues, it is probable.

The Pearl Harbor attack caused substantial damage to the U.S. Navy but, more significantly, enraged an American public conditioned to looking inward. Without such a provocative attack it is doubtful that American leaders could have summoned this resolve organically without a looming enemy threat. However, it is likely that American energy would have been focused on Imperial Japan. Absent a German declaration of war against the U.S., American military involvement in Europe would be untenable.

Undoubtedly, the attack on Pearl Harbor was a major event in history, rivaling the Battle of Britain in consequence. However, without the steadfast and courageous stand by the RAF in the Battle of Britain, World War II may have been solely a Pacific War.

Roosevelt’s sympathies clearly lay with the UK. Despite Ambassador Joseph P. Kennedy’s dour assessment of England’s chances against Germany, FDR found ways to provide tacit and material support, including the Lend-Lease initiative.

The efforts of the office of the British Security Coordination in Rockefeller Center cannot be ignored, either. These analysts conducted a determined and ultimately successful campaign to influence American public opinion through various means.

In the East, Hitler would likely have pursued his Lebensraum (“Living Space”) campaign well into Soviet territory. But the losses in the Battle of Britain would pale in comparison to casualty numbers in the East, and replacing skilled pilots was difficult.

Moreover, the timetable for Operation Barbarossa may have begun in 1940 or, at the latest, early 1941, potentially avoiding the disastrous consequences of the Russian winter. Without the distraction of a western campaign, the Germans may have well captured Moscow, the Soviet nerve center, leaving Stalin in a precarious political position.

North Africa, the Mediterranean, and the important sea lanes of the Suez Canal and Gibraltar would have fallen to the Germans. A push towards Iraq and Persia would have been feasible.

The Battle of Britain allowed the American public to see and hear the drama unfolding among their English-speaking cousins. Edward R. Murrow’s regular broadcasts brought the devastation and hardship to life for those perched around their radios. The barbarity of bombing civilian targets was not only featured under the “International Situation” in the New York Times but also in their own living rooms.

The victory reinforced the “special relationship” shared by the two countries. It allowed the U.S. time to mobilize its small and antiquated army, which only equaled Portugal’s in manpower in 1940. Later i

n the war, England would provide a staging area for not only the D-Day invasion but also sustained strategic-bombing campaigns conducted by the U.S. Eighth Air Force.

Without the Battle of Britain, there may never have been a world war at all. In a case of tragic irony, despite the staggering human cost, the absence of World War II may have made the world a more dangerous place.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments