By David A. Norris

Before dawn on the chilly morning of March 19, 1865, a detachment of Union foragers under Captain Charles Belknap downed the last of their coffee and rode out of camp, “tired, sore, cross, and ugly, but every man in his place.” For weeks, mounted foraging details had set out each morning ahead of Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s army as it tore through South Carolina and into North Carolina. Belknap’s 90-man patrol, armed with repeating Colt rifles and Spencer carbines, advanced two miles from camp before scattering an enemy picket post in the dark. So far as they knew, it was only a minor outpost of Brig. Gen. George Dibrell’s small cavalry division. Belknap thought they had a good chance of surprising and overrunning one of Dibrell’s camps.

It was fully light when Belknap’s band crossed a swamp, plunged through some brush, and ran into more Confederate pickets. The Federal troops broke up the picket line, then rode over a small rise. Expecting perhaps a handful of tents, they spotted something that was not supposed to be there at all—the entire Confederate Army of Tennessee. Belknap took in “a line of earthworks not forty rods away. As far as I could see to the right and the left the dirt from thousands of shovels was flying in the air.” General Joseph E. Johnston had managed to arrange quite a surprise for Sherman near the village of Bentonville. Belknap and his men were the first to be caught in Johnston’s trap.

Sherman’s March Into North Carolina

Sherman, a few miles away, knew nothing of the rapidly assembling Confederate force. At a country crossroads, he conferred with Maj. Gens. Henry W. Slocum and Jefferson C. Davis. Slocum commanded the left wing of the army; the right was led by Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard. After departing Atlanta on November 15, 1864, Sherman’s army had hollowed out the interior of the Confederacy with relentless and mechanical efficiency. Sherman saw nothing to delay Slocum’s troops on the coming day’s march toward the Neuse River and Goldsboro.

But a persistent and worrisome sputter of musketry in the distance made Davis fret that his advance elements were likely to encounter more than the usual cavalry opposition. Sherman disagreed. “No, Jeff,” he said. “There is nothing there but Dibrell’s cavalry. Brush them out of the way.” Since Atlanta, little effective resistance had been put in Sherman’s path by the dying Confederate states. This time, things would be different. Johnston did not intend to be brushed away so lightly.

Sherman’s cavalry had reached North Carolina on March 3, and his infantry entered the Old North State from South Carolina five days later. On March 8, a brief interval of pleasant weather turned into a harsh night of incessant and heavy rain. Soldiers struggled to push or pull wagons and guns through the deepening mud. Thousands of pine torches flared and smoked, lighting the way for the march to continue long into the night. Sherman was closing in on Goldsboro, an important railroad junction in eastern North Carolina. There, the east-west-running North Carolina Railroad intersected with the north-south-running Wilmington & Weldon Railroad, a vital Confederate transportation route during most of the war. With the blockade-running port of Wilmington now in Union hands, the railroad would be used to transport supplies to Sherman’s army instead.

Marching to join Sherman’s 60,000 men at Goldsboro were another 40,000 men under Maj. Gens. Alfred Terry and John Schofield, who were advancing from New Bern and Wilmington. With his reinforced army, Sherman could move on to the state capital of Raleigh, then march north to join Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s massed Union forces in Virginia. Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia would be effectively surrounded.

Confederate Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry had harassed and delayed Sherman on his march across Georgia, and Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee’s infantry and some cavalry dispatched from Virginia under Lt. Gen. Wade Hampton stood ready to offer more resistance in South Carolina. For the most part, however, the enemy force had little effect on slowing Sherman’s advance. By the time he crossed the North Carolina border, Sherman had mentally dismissed any chance of the Confederates massing enough troops to stop him.

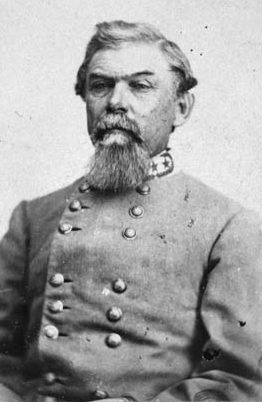

His old adversary in the Georgia campaign, Joseph E. Johnston, had been given the task of organizing a last stand in North Carolina. Taking over command of the Department of Florida, Georgia and South Carolina, as well as the remnants of the Army of Tennessee and the Department of North Carolina, Johnston had been directed—somewhat optimistically—to “thwart the designs of the enemy.” It was a little late for that. Johnston began drawing together the various units of his new command. Scattered as far away as Mississippi, it would take time to assemble all his forces, given the South’s overloaded and failing rail network. With Sherman now in North Carolina, time was in short supply.

After entering south-central North Carolina, Sherman’s cavalry commander, Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick, hoped to catch and destroy Hampton’s cavalry. Camped at Monroe’s Crossroads on the night of March 9, the overconfident Union general awoke to a crescendo of shots and commotion as his camp was surprised and overrun by Hampton. Leaving his mistress behind in his tent, Kilpatrick escaped in his underwear. Although Kilpatrick managed to rally his men and take back their camp, the action was remembered as “Kilpatrick’s Shirt-tail Skedaddle.”

Hampton withdrew to the Cape Fear River port of Fayetteville, linking up with Hardee’s infantry before abandoning the city on March 11. Sherman quickly moved in to destroy one of the South’s most important arsenals before resuming his march toward Goldsboro, where he hoped to replenish supplies. Despite the aggressive foraging parties and the lawless plundering by the informal “bummers” stripping the countryside of any and all edibles, it was difficult to feed 60,000 troops. Cut loose from the Union Army’s vast supply system, Sherman’s men were showing signs of wear. Uniforms were falling apart, and some of the men were without shoes or hats. Adding to their feeling of isolation, the soldiers had also been cut off from any mail since they left Savannah on February 1.

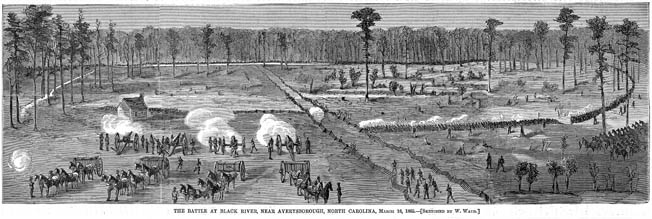

Sherman’s army moved in two wings, each numbering about 30,000 men. Dividing his forces into two wings allowed damage and destruction to a wider swath of Confederate territory. It also made it easier to move it along the available roads, which were rough at the best of times and were now deep in mud from a long spell of above average rain. On some days, progress was possible only after building four or five miles of corduroy roads—pine saplings and fence rails split in two and laid across the mud to make roadways. Rising waters soon washed the roads away, requiring an ever fresh supply of wood. The XIV and XX Corps, under Slocum, made up Sherman’s left wing. Slocum’s route was the partially finished Fayetteville-Raleigh Plank Road, which ended at a hamlet called Averasboro. Twenty miles to Slocum’s east, Howard’s XV and XVII Corps marched toward Goldsboro.

To buy a little time for Johnston, Hardee pitched into Slocum at Averasboro on March 15 and 16. Hardee held up Slocum for two days before breaking off battle. The battle served the twin Confederate goals of delaying Slocum and forcing some distance between the two wings of Sherman’s army.

Unable to take on all of Sherman’s forces, Johnston’s only chance was to fall upon each wing separately. It had to be done quickly; at Goldsboro as many as 40,000 more Union troops from New Bern and Wilmington were available to join Sherman. On the morning of March 18, Confederate cavalry reported that both wings of the Union army were on the move toward Goldsboro. Slocum was still near Averasboro; Howard was about one day’s march ahead, on a parallel road a dozen miles away. Johnston resolved to seize the chance to fall upon Slocum’s isolated detachment.

Smithfield, the county seat and only major town in rural Johnston County, offered Johnston a likely spot to assemble for an attack on Sherman. At the edges of the state’s coastal plain, Johnston County was more rolling than the flat Tidewater country, but not as hilly as the Piedmont. Forests of longleaf pine soared 100 feet in height. Nearby, the North Carolina Railroad allowed the transfer of troops and supplies from Raleigh, Greensboro, and Charlotte. To the east, the line was still open to Goldsboro, but Union forces were rapidly closing in from the east.

Assembling at Smithfield were General Braxton Bragg and the troops of the Department of North Carolina, including Maj. Gen. Robert F. Hoke’s brigade from the Army of Northern Virginia. Also on hand was Lt. Gen. Alexander P. Stewart, at the head of the remnants of the Army of Tennessee. Six miles west of Smithfield at Elevation (a community named for its hilly environs) were Hardee and his two divisions. Also assigned to Johnston were any miscellaneous contingents that could be spared. His new army contained soldiers from all 11 Confederate states as well as the border state of Kentucky.

Hardee, Hoke, and the other commanders made up a veritable Who’s Who of the Confederate Army. Major General Daniel Harvey Hill had gained national fame with the June 1861 Battle of Big Bethel, the South’s first land victory after Fort Sumter. Hoke, as well as Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws, had served with the Army of Northern Virginia. Besides Stewart, Hardee, and Bragg, senior commanders from the ill-fated Army of Tennessee also included Maj. Gens. Stephen D. Lee and Benjamin F. Cheatham. Hampton headed Johnston’s cavalry, with the able assistance of “Fighting Joe” Wheeler.

Planning the Attack on Bentonville

On the night of March 17, Hampton camped near Bentonville, a small unincorporated hamlet 15 miles south of Smithfield. Military maps showed Bentonville as a small clump of buildings south of Mill Creek, astride a road known as the Devil’s Racetrack. There were no more than a dozen structures in the whole village. Hampton prepared a surprise attack on Sherman’s left wing. Two miles south of the village was the Goldsboro Road, where Slocum would soon pass. Much of the area was covered in blackjack oaks, a small scrubby variety of oak that often grew in wild, tangled thickets. North of the Goldsboro Road, the plantation of Willis Cole offered stretches of open fields. With the Confederates dug in at the edges of the fields, they could lure the Federals in and decimate them from the protection of their earthworks.

There was one great danger for a Confederate stand at Bentonville. Half a mile away was the only bridge crossing Mill Creek, a deep stream that wound north and west of the village. Wheeler warned on March 19, “I fear that Mill Creek is so full that it can’t be forded.” Its western tributary Stone Creek could be crossed, but only at one point, and then only by single file. With Sherman to their south, any Confederate withdrawal to the north and west would be impeded by Mill Creek, and escape to the east was blocked by the Neuse River. Holding the Mill Creek Bridge near Bentonville could become a matter of life or death.

On March 18, the XIV and XX Corps marched along a muddy road under alternating spells of rain and bursts of bright sunshine. Turpentine distilleries, set on fire by the Federals, poured thick columns of dark smoke into the air. The smoke served as directional markers to the followers in the Union column as well as Confederate cavalry in the region.

Johnston agreed to the plan of attacking at Bentonville. As he had not been able to scan the ground himself, he trusted Hampton for the broad outlines of where to post his troops. It would take time to march the infantry in from Smithfield and Elevation, so it was imperative that Hampton and Wheeler delay the enemy as much as possible to keep them from reaching Cole’s Plantation before defenses were ready.

All morning, hovering around cabins and farmhouses along the road or peering from the cover of woods and thickets, mounted Confederates kept an eye on the marching column. Periodically, the Union troops halted when confronted by small ambushes or occasional cannon fire. A correspondent for the New York Herald reported that one Confederate cannon shot killed two foragers and four horses. Each delay was in itself a minor victory, as it allowed Johnston’s scattered units to plod a little closer to their rendezvous.

At a farm owned by a family named Cox, Brig. Gen. William P. Carlin was struck by the agitated and fearful attitude of the civilians. Carlin offered to post some guards to protect their house, but Cox replied, “Oh, that won’t save us!” Carlin pondered Cox’s anxiety. He concluded that Cox knew that a large Confederate army was gathering and that his farm was in danger of being a battleground. The information was passed up the chain of command, but Sherman airily dismissed the notion. “Oh, no,” he scoffed. “They won’t fight us this side of Smithfield or Raleigh.”

Carlin’s division was selected to take the lead for the march on Sunday, the 19th. Despite Sherman’s nonchalant attitude, Carlin had a sense of foreboding. Convinced there would be a battle, he put on his best uniform so that he could be recognized in the event of his capture or death. That morning, Carlin was awakened early by what sounded like irregular skirmishing. Only 500 yards from camp, the foragers of his division were blocked by a heavy Confederate skirmish line. The Federals took cover behind fences and returned musket fire.

“Brush Them Out of the Way”

Sherman, who had been with the left wing, conferred with Slocum and Davis about 6 am, before heading out to join Howard and the right wing. Their talk was interrupted by the sound of Hampton’s men skirmishing with Carlin. Davis expressed his growing concern; it seemed to be much more intense than the usual light harassment sometimes directed at the foragers at the start of their morning routine. But Sherman had grown used to having things his own way against the Confederates. “Brush them out of the way,” said the commander as he left to join Howard.

Carlin’s men captured a few Confederate prisoners early that morning. All of these prisoners were from Dibrell’s cavalry division, and none of them gave away the presence of their infantry, which was digging in behind them. Wanting no delays, Slocum ordered Carlin to attack vigorously and push on.

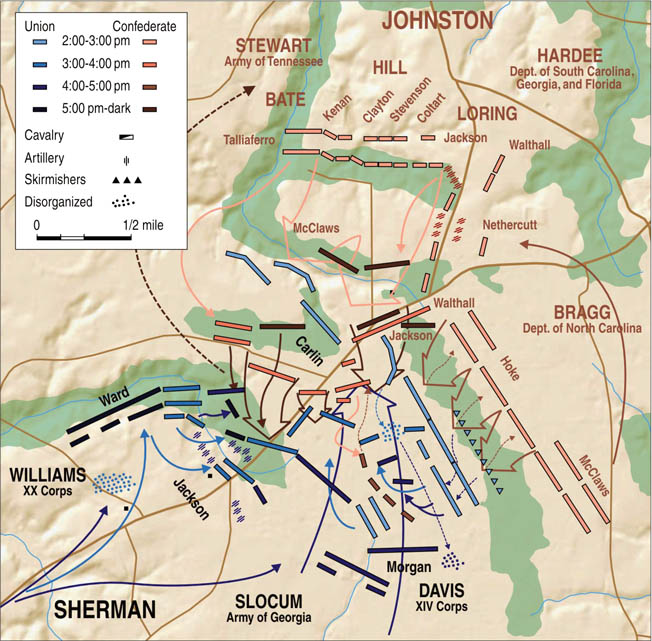

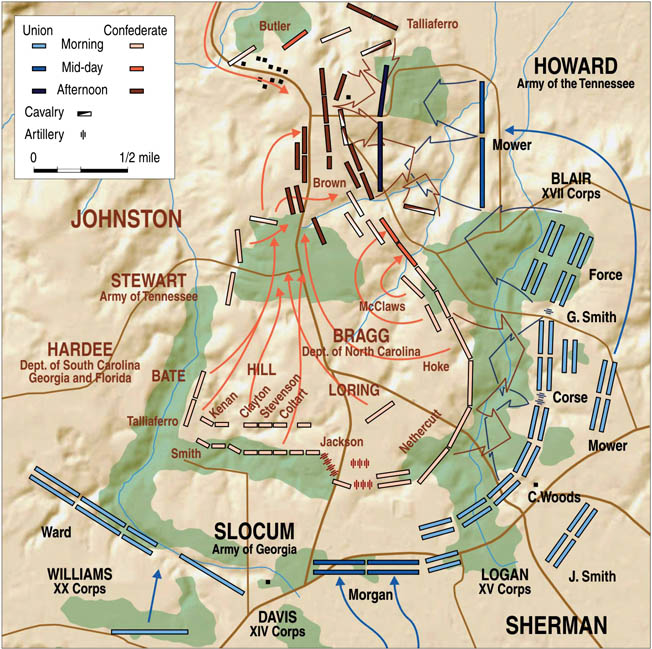

So far, the Federals didn’t realize that the enemy skirmishers masked a rapidly assembling army. Bragg’s troops, under the active command of Hoke, blocked the Goldsboro Road. Hoke’s center at the road formed the point of a shallow V, with his left south of the road and his right north of the road bent to the rear to conform with the edge of an open field. A short distance from Hoke’s right began the Army of Tennessee, under Stewart, extending in a roughly perpendicular direction. On a map, the Confederate deployments resembled a net, with Hoke’s left as the handle.

Much of the countryside was covered in thick woods and cut by streams and swamps that hampered Confederate movements. Stewart’s men, funneled through a single road, were still filing into place well after daybreak. Hardee was supposed to hold the gap between Hoke and Stewart, but he delayed even longer than Stewart. Johnston ordered him to use a road from Elevation that was suggested by the county sheriff, but the road was not on Hardee’s maps. The gap between the two forces was plugged with Hart’s and Earle’s batteries, two horse artillery units attached to Hampton’s command.

As the Army of Tennessee started digging in, Belknap’s foraging party suddenly appeared in its front. The Union foragers quickly splashed back across the swamp they had just ridden out of. Belknap dispatched a courier to Carlin with a warning of what was awaiting them. Later, Belknap’s men captured two Confederate prisoners who revealed that Johnston’s entire army was present. Both captives were sent under guard to Carlin.

Carlin was left for a considerable time to deal blindly with the growing threat. Used to easily driving off small enemy forces in their way, the Federal horsemen grumbled that the Confederates didn’t “drive worth a damn.” Belknap’s messenger was never seen again. The two captured Confederates and their escort got lost for so long that by the time they found Carlin, Johnston’s surprise arrival was old news. Early in the fighting, Slocum sent Major E. W. Guiden with a message to Sherman. Slocum was worried about the growing battle noise, but only that it might delay Sherman and Howard from their march. “I should not need assistance,” advised Slocum, who was confident he would reach the Neuse at the appointed time.

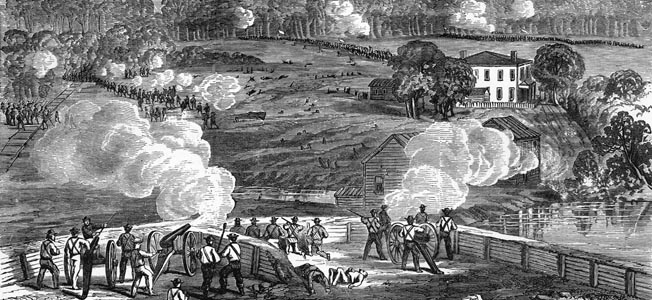

Carlin reinforced his skirmishers with half of Brig. Gen. Harrison C. Hobart’s brigade. They plowed ahead, driving Hampton’s skirmishers from a line of lightly held works. But when they drew within range of Hoke’s men at Cole’s Plantation, a storm of Confederate musket and cannon fire drove them back. Continuing his push, Carlin ordered attacks by Brig. Gen. G.P. Buell’s brigade, to Hobart’s left, and Lt. Col. David Miles and his brigade on the right.

Hoke held a sketchy line of shallow defenses, and part of his position was held by three regiments of North Carolina Junior Reserves, who except for the officers were untried soldiers all 16 or 17 years of age. The ever cautious Bragg worried that Hoke was in danger of being driven out of his entrenchments. Pleading with Johnston for reinforcements, just as Hardee’s forces were trickling onto the field Bragg succeeded in getting McLaws’ division peeled off to reinforce Hoke. McLaws’ men found themselves slogging through swamps and thickets, and their guides kept getting lost. By the time McLaws got to Hoke, the attacks had stopped and he was not needed. However, the diversion of McLaws weakened the major attack Johnston was about to unleash.

Buell and Miles were also thrown back from their run at the Confederate lines. Amid the commotion of the attacks by Carlin’s brigades, three soldiers among the Confederates let themselves be captured. All claimed to be Union captives who became “Galvanized Yankees,” getting out of POW camps by joining the Confederates. One of the three claimed that the Union was facing all of Johnston’s army. Union officers were skeptical until Major W. G. Tracy, one of Slocum’s aides, recognized one of the men as a fellow New Yorker he had met before the war.

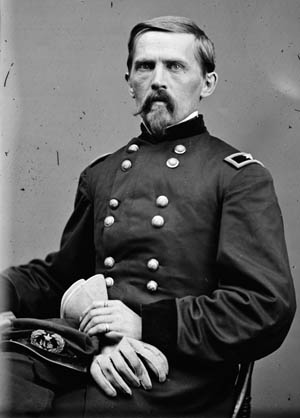

Now fully aware of the danger, Slocum sent Major Joseph Foraker with a message explaining that he was confronted by Johnston’s entire army and asking Sherman to send reinforcements. He also sent to the rear, ordering the XX Corps to come up as quickly as possible. At the same time, Brig. Gen. James D. Morgan brought his XIV Corps division to the front, and it settled in to Carlin’s right, south of the Goldsboro Road. Morgan quickly got his men to work building log defensive works. Quite soon, the outcome of the battle would depend in part on these defenses.

Johnston’s plans were still in motion, although disrupted by Carlin’s attack and Bragg’s diversion of McLaws’ brigade. As the Confederate commander readied his last roll of the dice, Morgan’s men were bolstering their entrenchments, and elements of the XX Corps were joining them. Brig. Gen. James S. Robinson’s brigade filed in between Hobart and Miles. It quickly set to building breastworks, although the soldiers had nothing but hatchets to work with.

By 2:30 pm, Johnston was readying his attack. Hardee would take charge of the Confederate right. There was another brief delay when Maj. Gen. William Bate, on the Rebel right, requested that Taliaferro’s division be dispatched to his right to make a flanking attack on the Union left. Taliaferro was still moving into place at 3:15, when the Army of Tennessee advanced in two lines toward Slocum’s troops. Lt. Col. Charles W. Broadfoot, commanding a regiment of Junior Reserves, remembered, “It was painful to see how close their battle flags were together, regiments being scarcely larger than companies and a division not much larger than a regiment should be.”

As the Army of Tennessee surged forward, the brigades of Buell, Robinson, and Hobart broke. Carlin saw the Confederates in the rear and said, “No use, boys,” and ordered a withdrawal. His three brigades fell back a mile to the XX Corps position. Also driven out of its lines, Miles’s brigade joined Morgan’s division, entrenched south of the Goldsboro Road.

Peter Anderson’s Medal of Honor

Several hundred yards behind Carlin was the Riddick Morris farm, where Slocum had his headquarters and surgeon Waldo Daniels had set up the XIV Corps hospital. Daniels and his staff had been busy for hours sawing off arms and legs of wounded men. “Pale and bloody men lay under the blooming peach trees,” observed a newspaper reporter. As Carlin’s line collapsed, his men fled to the Morris farm, pursued by the enemy. Bullets plunked into the log walls of Morris’ house, and shells landed among the Union wagon park nearby. Daniels ordered a hasty withdrawal half a mile west to the home of John and Amy Harper, where he set up a new hospital.

As the Union infantry buckled, three guns from Captain Samuel D. Webb’s 19th Indiana Battery were left unsupported and were captured. The fourth gun was saved by the quick thinking of Private Peter Anderson of the 31st Wisconsin. Anderson almost didn’t make it to the battle; he had fallen sick and that morning had been ordered to ride in an ambulance. But as he put it, “I preferred the ranks.” In the fighting, Anderson’s regiment was swept back by the Confederates, leaving Webb’s battery stranded. One of the guns was visible, its horses hitched before the gunners had been driven away. Unable to get volunteers to join him, Anderson ran toward the gun alone. Anderson tried unsuccessfully to mount one of the draft horses—a passing bullet cut the stirrup—then continued running on foot, driving the horses by wielding his ramrod as a whip.

When Anderson paused to load his musket, another bullet tore off the tip of his right forefinger. He raised his weapon in such haste that he “blazed away, sending ramrod and all into the rebels.” With his empty musket, Anderson seemed doomed to capture when a Confederate officer rode up to him, pointed a revolver to his head, and demanded his surrender. The next instant, a bullet killed the Confederate officer. Anderson escaped with the gun. Overtaking his regiment, he exchanged the cannon for another musket and went back into the line. Three weeks later, Anderson was awarded the Medal of Honor and promoted to captain.

Hardee paused after his wave of success to regroup his units. Although perhaps necessary, the halt stalled Confederate momentum, and Bragg’s failure to order Hoke’s troops to join the attacks near their peak dampened their chance of success. While Hardee pressed his attack south of the Goldsboro Road against Morgan’s division, Davis ordered Morgan’s reserve brigade into action. Under Brig. Gen. Benjamin Fearing, they charged and managed to stall Hardee’s advance for a time. At last, outnumbered and yielding to pressure, Fearing withdrew and formed a new line about 300 yards back, anchored with its left on the Goldsboro Road.

Fearing had bought some time for Morgan, but his retreat opened a gap exposing the rear of Morgan’s division. Some of Hardee’s troops charged through the gap left by Fearing and moved behind Morgan’s entrenchments. Morgan’s troops were surrounded and fought part of the time from both sides of their breastworks. Even the headquarters guard and the general’s personal escort were thrown into the battle.

Hoke wanted to exploit this opportunity and join Hardee, but he was overruled by Bragg, who instead ordered a costly frontal assault. Hoke’s command took heavy casualties while assaulting Morgan’s front, without shifting the Union division. Had Hoke attacked from the rear and succeeded, Morgan’s division would have been driven back rather than serving as an anchor to steady the Federal lines for the rest of the day.

To the west of Morgan’s position began the lines of Maj. Gen. Alpheus Williams’ XX Corps. Williams’ right was held by Robinson’s brigade, which has been earlier driven back in the Army of Tennessee’s initial charge. Now Robinson held a point on the Goldsboro Road. Some 400 yards separated Robinson’s left from Colonel William Hawley’s brigade, but the gap was exposed to artillery and reserve troops. As the XX Corps waited for the inevitable attacks, Williams ordered his guns loaded with double shots of canister. His gunners scrounged bullets from the infantry, wrapped handfuls of them in rags, and rammed them in after their canister rounds.

A series of Confederate attacks on the XX Corps began about 5 pm. Bate, Taliaferro, and McLaws formed their troops and charged five times, but each time were driven back by musket and cannon fire. By the time the last charge was over, after sundown, about 500 Confederates had been hit, twice the Union loss. Brig. Gen. John D. Kennedy of McLaws’ division found “the smoke was so thick that it was impossible to see ten yards ahead, hence I could form no idea of the force of the enemy in my front.”

As night approached, many of the soldiers in the field were caught up in confusion generated by the chaotic fighting, wooded terrain, and the approaching darkness. D.H. Hill said that the smoke of battle and thousands of smoldering pine stumps and logs made the night “darker than I had ever witnessed before.” Seventy of Hill’s men in the 45th Tennessee were cut off behind Union lines and only made it back to their own army nine days later.

On the Union side, Davis and Carlin narrowly escaped capture. Carlin, searching for Miles’ brigade, rode through a picket line in the deepening shadows. Plagued by doubt, Carlin scrutinized the men as best he could in fading light that made it hard to distinguish between a dark and dusty gray from a faded and dusty blue. The terrible truth dawned on the general that he had ridden through a Confederate picket line.

For Carlin, his only chance to escape was to ride back through them without being challenged. This he did. Moments later Carlin met his corps commander, Jefferson C. Davis, and warned him that he was about to ride into a Confederate skirmish line. Davis peered at the men in the dim light and snapped, “No they’re not!” Riding a few steps closer, Davis suddenly realized, “Yes, they are!” Davis called up a brigade to clear the woods, and minutes later, Carlin set out again to find Miles’ brigade. The enemy skirmishers through whom he had just ridden lay scattered, dead or wounded.

Across the battlefield as the firing ceased, the Confederates buried their dead and withdrew to the positions they had held in the morning. Rain started falling, and the soldiers spent a chilly night without fires. All the next day, Howard’s men heard the worrying rumble of cannon fire to their west. Howard dispatched General William B. Hazen’s division to turn around and aid Slocum. Sherman, who was farther away and was still under the impression that Slocum was only fighting stubborn skirmishing parties, cancelled the order. It was late in the evening when Sherman got a fresh report confirming that Slocum was engaged with Johnston’s entire army. The commander assured Slocum, “All of the right wing will move at moonrise toward Bentonville. All the army is coming toward you as fast as possible.”

March 20 was a day of continued but subdued fighting. By first light, elements of Hazen’s division, which had been part of Howard’s rear guard, were the first Union reinforcements to arrive. Wheeler harassed the Union marchers, but reinforcements flowed in all day. The entire Union army was assembled at Bentonville by 4 pm.

Johnston made major changes in his lines, shifting into a large V shape with the back or open end facing Mill Creek. This way, the Confederates were ready for attacks from their adversaries of the day before as well as Howard’s two corps, which they knew would be coming from the east. Broadfoot recalled his junior reserves digging in on that day, building log breastworks and filling them with dirt churned up by bayonets, tin pans, and a few spades and shovels.

Sherman now outnumbered Johnston by more than three to one. He was puzzled about what Johnston thought he could accomplish by holding on. Preferring to avoid further casualties, the Union commander hoped that Johnston would simply withdraw. Skirmishing sputtered all day, but there were no major initiatives. Johnston, for his part, hoped to lure Sherman into launching an all-out attack at the cost of tremendous Union casualties, but the main reason for lingering was the evacuation of the wounded. Smithfield was 15 miles behind the Confederate lines. The North Carolina Railroad’s tracks were four miles farther away; the railroad went around rather than through Smithfield. On March 20, surgeon John T. Darby, the medical director of the Army of Tennessee, tallied 624 wounded. The figure didn’t include the wounded in the rest of Johnston’s forces.

Mower’s Aggressive Attack

As the day faded, heavy rain began to fall again and pelted the battlefield all night. Johnston’s men, expecting orders to withdraw at any minute, got little sleep during the wet, chilly night. On March 21, Johnston was still in place behind his entrenchments. With faulty intelligence that claimed Johnston had double the numbers he possessed, Sherman still hoped to avoid a pitched battle. Nonetheless, the skirmishing was sharper than the day before. Union sharpshooters found cover in Cole’s farm and sniped at Hill’s men. At last, detachments of Bate’s and Walthall’s skirmishers drove out the sharpshooters and set fire to Cole’s home and outbuildings.

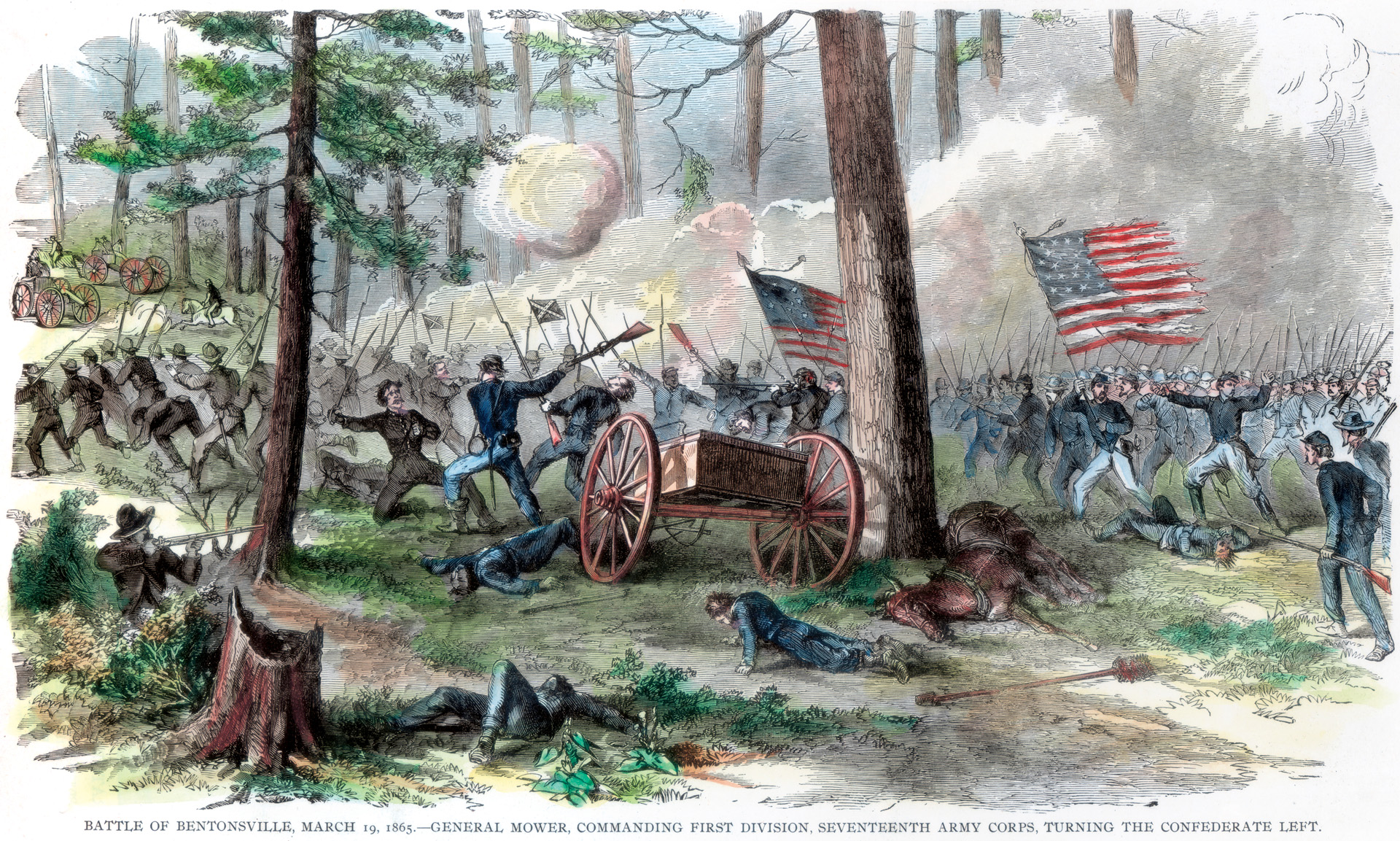

The action reached a critical phase about 4 pm, when Maj. Gen. Joseph Mower took two of his brigades around the Confederate left. His brigades tore through a thin line of pickets and found themselves on the threshold of taking the Mill Creek Bridge and trapping the entire Confederate army. Johnston and his staff dashed out of their headquarters just ahead of the advancing Federals.

Mower’s move left him dangerously isolated, nearly a mile from any support.

As Hampton and Hardee rushed in with their reserves, Hampton ran across Cummings’ brigade of Georgians and sent them to the scene. Led by Hardee himself, the 8th Texas Cavalry attacked Mower’s left. With the Texans was General Hardee’s only son, 17-year-old Willie Hardee. The general’s son had wanted to take an active role in the ranks for some time. He pleaded for his father’s permission to join in the fighting with the 8th Texas Cavalry, and the general consented. In his first minutes on the battlefield, Willie fell mortally wounded. Johnston commended him in a report, stating that he was “gallantly charging in the foremost rank.” Young Hardee was taken away for treatment but died three days later.

Hampton and Wheeler also threw in their cavalry to stop Mower. The chance for a decisive Union victory faded as the attacking Federals found themselves in an intensifying hornet’s nest of Confederate counterattacks. His attack on the bridge stalled, Mower withdrew to his original position to regroup and wait for reinforcements. Mower’s attack was much more aggressive than anything intended by Sherman. When the commander found out about the attack, he ordered Mower to stay in place. At the time, the attack on the Confederate left seemed a risky move to Sherman, who believed Johnston had enough troops to crush Mower. Sherman was still convinced that the Confederates were going to retreat anyway. Fighting faded away as rain fell again at sunset.

The Confederates pulled out of their earthworks about 10 pm. Handfuls of men lingered and fired occasional shots to cover the withdrawal as rain deluged blue and gray alike. By sunrise, the last of Johnston’s troops had filed across the Mill Creek Bridge. Only a last detail remained, with orders to burn the bridge. The persistent rains had soaked the bridge planks and timbers, making them nearly fireproof. Still struggling to kindle a blaze, the Confederates saw enemy troops. The Confederates pulled up as many floor planks as they could, tossed them into the creek, and took off.

Rushing to capture the bridge were Lt. Col. Ira Bloomfield and the 26th Illinois. Earlier, Bloomfield’s regiment had gingerly probed the Confederate line, finding that the enemy had gone. Bloomfield’s men rushed to Mill Creek to prevent the burning of the bridge. After repairing the bridge, the 26th Illinois followed the Confederates as far as Hannah’s Creek. Bloomfield’s men, finding the Hannah’s Creek Bridge on fire, attempted to save the span, but the Confederate rear guard opened fire with muskets and two guns loaded with grapeshot. Several Illinois soldiers, including the color bearer, were cut down. Slipping from the grasp of the dead color-bearer, the flag of the 26th fell into the creek. Lieutenant Arthur Webster and several men retrieved their colors from the water. Bloomfield’s horse was shot dead under him. At last the bridge was taken, but orders arrived for Bloomfield’s men to fall back. The Confederates were in full retreat, and Sherman was happy to let them go.

The Battle of Bentonville: A Clash Too Late

Confederate casualties at Bentonville were officially reckoned as 239 dead, 1,694 wounded, and 673 missing, for a total of 2,606. Sherman claimed a figure of more than 1,600 Confederate prisoners taken. The official estimate would put the losses at roughly one-eighth of Johnston’s force. Union losses were much lower: 194 dead, 1,112 captured, and 221 missing.

Johnston had achieved much with his ragtag army on the first day of the Battle of Bentonville. However, he did not have adequate reserves to follow up on his early success. It was simply too late for the Confederacy. On March 23, Johnston had 18,513 men, of whom 13,353 were deemed effective. Sherman had nearly 60,000 troops on hand; thousands more were only 20 miles away at Goldsboro. On that day, near Smithfield, Johnston sent a fatalistic telegram to Robert E. Lee: “Sherman’s course cannot be hindered by the small force I have. I can do no more than annoy him. I respectfully suggest that it is no longer a question whether you leave present position; you have only to decide where to meet Sherman. I will be near him.”

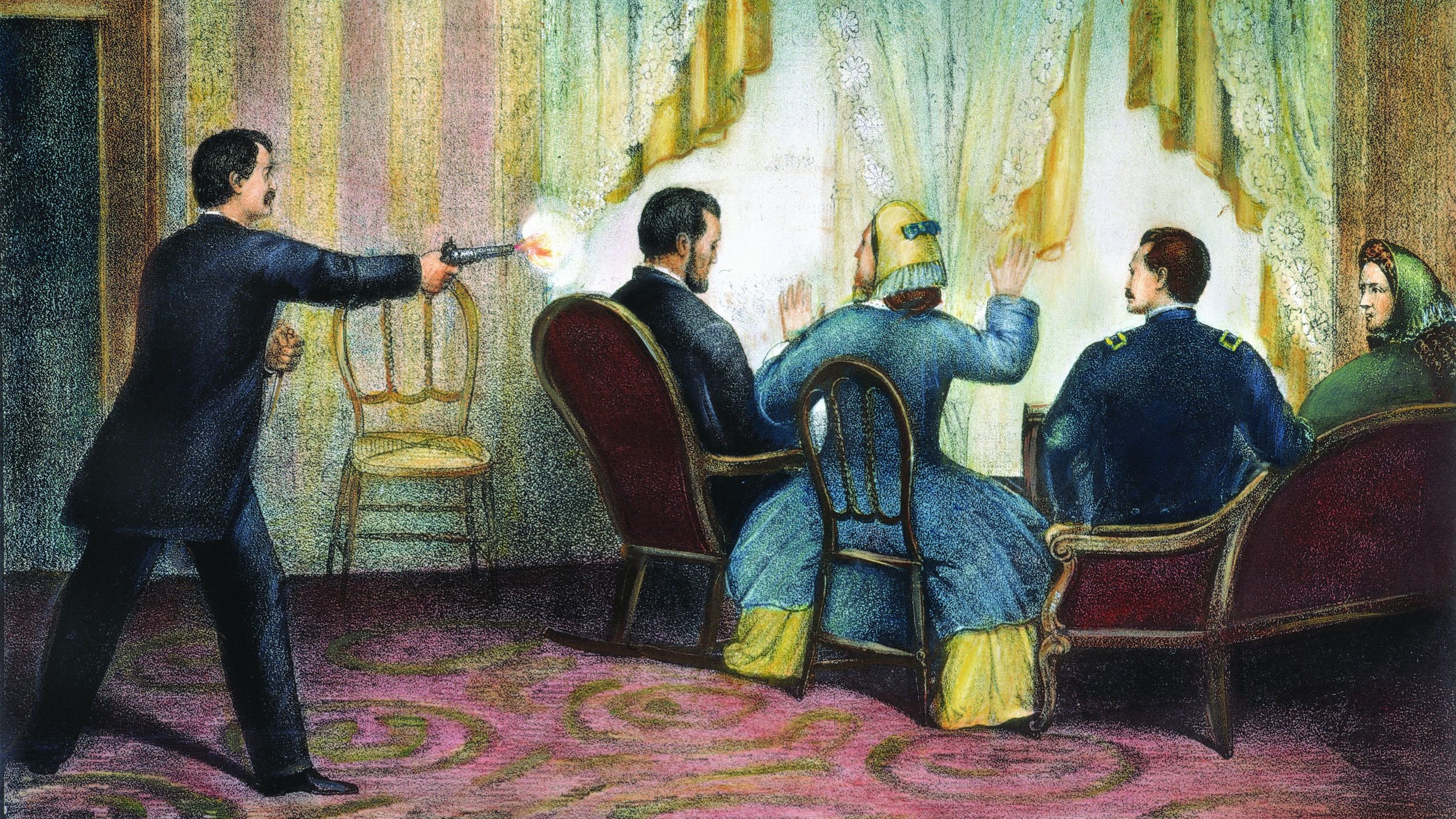

Johnston withdrew into the interior of North Carolina. Raleigh fell to Sherman on April 13. Five days later, Johnston and Sherman agreed to an armistice at the Bennett House, near Durham. On April 26, Johnston surrendered his army, along with all Confederate forces in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida. It was the largest single surrender of Southern forces and marked the end of the Civil War even more emphatically than Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Courthouse nearly three weeks earlier. On both major fronts, Confederate resistance had suddenly and conclusively ended.

Bentonville is about 40 miles from Raleigh just off of I-40. The battlefield is well defined and the farmhouse used as the hospital is well worth the visit. Two rooms were used as surgeries and a picture shows the piles of legs and arms that were amputated and tossed out the windows.

Joseph Wheeler was first a general in the Confederate Army, then served as a general in the US Army during the Spanish-American War. Fought in Cuba, retired as a major general, US Army.