By Allyn Vannoy

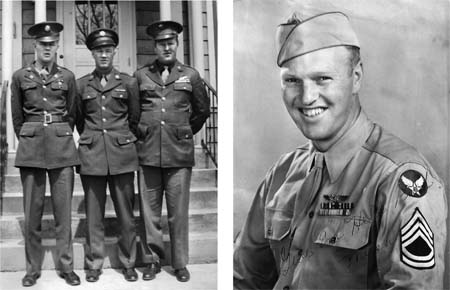

Marshall B. Haugen was born July 8, 1917, and raised in Duluth, Minnesota—one of four brothers, all of whom served in the U.S. Army during World War II. Marshall was a technical sergeant, radio operator, mechanic, and aerial gunner on B-17 Flying Fortress bombers. Fortunately, Marshall kept a detailed diary during his time in the service, allowing us an intimate look into the harrowing life of a bomber crewman in World War II.

Haugen had registered with the draft but was deferred since he was in college. He tried to enlist as a flying cadet but was not able to pass the physical exam due to a nose injury. Failing that, he enlisted in the Army on August 29, 1941, at Fort Snelling, Minnesota, with his friends Bud Forgette and Bob Lyons.

Five days after Pearl Harbor, Haugen was sent to radio school. He arrived at Scott Field, 25 miles east of St. Louis, Missouri, on December 12, then was transferred on May 26, 1942, to MacDill Field at Tampa, Florida. In the end, he was assigned to the 322nd Bombardment Squadron.

He recalled, “The sight of seeing a B-17 and my first flight are a couple things I will never forget.” Haugen was flying day and night and enjoying it. In late June, the squadron was transferred to Walla Walla, Washington, as it went into advance training in preparation for combat. While there, Haugen was promoted to sergeant. In August, the group left for Bangor, Maine, to obtain new planes and prepare for deploying to Europe.

On the morning of September 20, the unit departed for Gander, Newfoundland, ultimately destined for Bassingbourne, England, via Prestwick, Scotland, and Kimbolten, England. The squadron, now part of the 91st Bomb Group, reached its base of operations at Bassingbourne (just southwest of Cambridge), one of the best in England, where they would gain the nicknames “The Ragged Irregulars” or “Wray’s Ragged Irregulars” (a riff on its commander’s last name). The 91st (consisting of the 322nd, 323rd, 324th, and 401st Bomb Squadrons) was outfitted with the latest Boeing B-17F model. Haugen’s bomber was given the moniker Chief Sly.

On November 7, 1942, the 91st Bomb Group got its first mission, on which they would hit the German U-boat base at Brest, France (near the western tip of Brittany), with 23 B-17s and 11 Consolidated B-24 Liberators. By 9:30 am, the bombers, each loaded with 5,000 pounds of bombs, were on their way.

Unfortunately, four of the .50-caliber machine guns on Haugen’s B-17 failed during test firing over the English Channel, forcing them to turn back. The rest of the aircraft in the group continued the mission, and all returned safely.

In 1942, the German submarine force became a key target of the Allied air offensive as the Battle of the Atlantic was reaching a new level of intensity, with U-boats sinking between 400,000 and more than 700,000 tons of Allied shipping a month.

On November 14, the group was dispatched to hit the U-boat pens in the La Pallice district of La Rochelle, France, but the target was covered by heavy clouds, so 15 B-17s and nine B-24s were directed to hit a secondary target, the nearby port area at St. Nazaire. Only four aircraft from the 322nd took part, each loaded with two 2,000-pound bombs with which to crack the thick concrete roofs of the sub pens. This was Haugen’s first combat mission.

Though the flak was intense, all the aircraft came through. On the return flight, the group landed at another field, Davistin Moore. Weather delayed the return to the group’s home base for two days.

During the flight back to Bassingbourne, one of the life rafts on Haugen’s bomber broke loose and became lodged in the horizontal stabilizer. The plane went into a dive and was only brought under control through the extreme efforts of the pilots. The crew prepared to abandon ship, but the B-17 was too low to jump by the time they were ready. One of the waist gunners managed to shoot the raft loose, or at least relieve some of the pressure, and they were able to make an emergency landing. That same day, Haugen discovered he had been promoted to technical sergeant.

On December 6, the group was ordered to hit the Atelier d’Hellemmes locomotive carriage works at Lille in northern France, dispatching 22 aircraft as part of the 103 heavy bombers taking part in the mission. When Haugen’s crew test-fired their guns after takeoff, they found that the top turret was not working and were forced to turn back.

On December 12, the group was sent to hit an aircraft depot 75 miles southeast of Paris at Romilly-sur-Seine as part of a 90-bomber attack force. The mission crews anticipated that it would be a “hot trip” as it was a long way without fighter protection. The target, though, was hidden under heavy cloud cover, so the strike was rerouted to hit a secondary target: the marshaling yards at Sotteville-les-Rouen, northwest of Paris along the Seine. Of the 19 planes of the group that took off, only six reached the target as part of the 78 bombers that made the strike. Haugen’s B-17 was forced to turn back due to engine trouble.

On December 20, 80 B-17s and 21 B-24s of the Eighth Air Force’s First Wing were dispatched again to hit the Luftwaffe air depot at Romilly-sur-Seine. Of the 91st Bomb Group’s 17 planes that took off, all reached the target. German fighters were encountered 30 miles from the coast and engaged the bombers from there to the target and back to the coast.

The group lost two aircraft, both to enemy fighters. Another caught fire after taking a hit to its no. 3 engine, forcing it to fall out of formation. Two others, including Haugen’s, followed the wounded bird in to provide cover. Of the 72 bombers that struck the target, six were lost to German fighters.

“We beat off frequent attacks all the way to the target and all the way back,” Haugen wrote. “Two planes from the 401st Squadron went down on the way in. They were flying in the element directly behind us. We made it to the target and dropped our bombs okay. It was on our way back that we really ran into trouble. The lead plane in our element was hit and started to lag behind, so we stayed with it while the others went on ahead. That is when all the FW’s [Focke-Wulf 190s] in France started to pick on us. The main attack started 12 minutes from the Channel, and they swarmed around us like bees. Soon, our plane was riddled with holes, and our no. 3 engine was out.

“Then our no. 4 was hit, and practically the whole tail assembly was shot away. During the onslaught, a 20mm cannon [shell] exploded within a foot of my head, but I wasn’t scratched. The radio room was full of holes. We were unable to stay with the other two planes in our element and went into a dive. As luck would have it, we ducked into a cloud and thus shook off the pursuing fighters. Just as we disappeared into the cloud, a fighter let go on a final blast that hit our navigator in the leg.

“During the heat of the battle, our gunners shot down at least six fighters, but I didn’t get a shot. All of the attacks came at the nose, and I was unable to get my guns in that direction. My gun shot only to the rear to protect against tail attacks. The plane was so badly damaged that we were all set to make a belly landing in the water; however, our pilot, Lt. Barton, and co-pilot, Lt. Reynolds, got the plane under control, and they decided to try their darnedest to make England.

“It sure was a sweet sight to see land, but we still had the problem of putting the plane down. Most of the radio equipment was shot away and so we were unable to make contact with any airdromes. Time was the main thing, as we didn’t know how long we could keep going on two engines. We looked for an airdrome, but being unable to find one, our pilot had to belly-land in a field. We landed in a plowed field, and the plane didn’t even break in half. As a matter of fact, it hardly jarred us.”

Chief Slyhad holes everywhere, and the tail was practically gone. One 20mm shell left a hole eight feet by three feet in the vertical stabilizer. Additionally, the ship’s attackers had peppered it with numerous .30 caliber bullet holes. The aircraft was written off as a loss, and eventually Chief Slywas replaced by Chief Sly 2nd.

On December 29, an RAF Short Sterling (a four-engine heavy bomber) was flying near Haugen’s airfield when it developed engine trouble and tried to land. But it fell out of control at about 200 feet, then plunged to the ground and burst into flames, impacting just 200 yards from where Haugen was standing. Haugen ran to the wreckage to help, but the only survivor of the seven-man crew was the pilot, who was thrown clear.

Five days later, on January 3, 1943, Haugen was assigned to fly with another crew for a raid on St. Nazaire, his seventh mission. He was not anxious to fly with his new crew. The primary target was the St. Nazaire U-boat base. The 1st Bombardment Wing dispatched 85 B-17s from the 91st, 303rd, 305th, and 306th Bombardment Groups and 13 B-24s of the 44th Bombardment Group of the 4th Bombardment Wing.

They encountered heavy flak for some eight minutes and were harassed by enemy fighters in large numbers from the target to some 45 minutes out over the Atlantic on the return flight. The groups participating in the raid lost seven aircraft. While Haugen’s Fortress took frequent flak hits, no one was wounded. Formation, instead of individual, precision bombing was used for the first time, with considerable damage done to the dock area.

The first raid by American bombers into Germany came on January 27, 1943. The 1st Wing dispatched 25 aircraft, of which the 91st Group provided 17, four coming from the 322nd Squadron. Haugen had looked forward to striking Germany, but when the bomber was within 50 miles of the German border, its no. 2 engine began running rough, forcing the crew to abort.

Haugen’s second mission to Germany came on February 4, with the squadron commander, Captain Fishburne, in his plane’s co-pilot seat. The group dispatched 17 aircraft loaded with 10 500-pounders as part of a strike by 65 B-17s of the 1st Bombardment Wing and 21 B-24s of the 2nd Bombardment Wing against the railroad marshaling yards at Hamm, Germany.

The B-24s turned back before reaching the Dutch coast when the temperature dropped to -40 degrees Celsius. Because of cloud cover at Hamm, the B-17s were redirected to Emden, Germany, instead. The squadron’s daily report indicated that they were attacked by 75 to 80 enemy aircraft for an hour and 15 minutes. It was also noted that the bombers were opposed for the first time by Ju-88 and Me-110 twin-engine fighters.

“We had a perfect position in the formation as we led the second element,” wrote Haugen. “The overcast was heavy, and we were unable to bomb our primary target. Just what we finally bombed I don’t know. We had comparatively light flak over the target, but fighters picked us up shortly before reaching the target and followed us 78 miles back out over the North Sea.

“Our group lost two planes, both from the 323rd Squadron. One of the radio operators lost was a fellow Minnesotan and a close friend, Cyril Curb. We were in the same barracks at Scott and we graduated together…. Our plane had a couple flak holes. It looks like Germany will be our main target from now on.”

Haugen next spent a 48-hour pass in London, his crew getting together at the Regent Palace. “A lot of fun was had by all,” he noted.

On February 13, Haugen and three members of his crew took part in a CBS network radio broadcast, with CBS’s Robert (Bob) Trout as the reporter. Trout lived on the base for two days and interviewed the crew before deciding to put them on the air.

The next day, February 14, they were directed to the Ruhr.

Haugen wrote, “We got in far enough to have flak shot at us. It must have been aimed by use of radio, as they certainly couldn’t see us. The altitude of the flak was perfect, but it was quite some distance behind us.”

On the next raid, February 16, 71 B-17s of the 1st Bombardment Wing and 18 B-24s of the 2nd Bombardment Wing were dispatched against the locks and U-boat base at St. Nazaire. The bombers that reached the target dropped 160 tons of bombs. The bombing was reported as excellent, the flak accurate along with 50 to 60 enemy aircraft appearing.

The crews claimed 20 Luftwaffe aircraft destroyed, 12 probables and two damaged, while bomber losses were six B-17s and two B-24s, with 28 B-17s and two B-24s damaged. All of Haugen’s group returned safely.

On February 26, the group headed to Bremen in northern Germany to hit the Focke-Wulf factory there, but due to overcast had to settle for the docks and surrounding areas of Wilhelmshaven on the coast. Seventeen aircraft of the 91st Group, commanded by Lt. Col. Baskin L. Lawrence, attacked the secondary target. The lead of the group was assigned to the 322nd. Bombing results were reported as fair, with the group losing two aircraft.

Haugen noted, “It was a fairly easy raid for us, as we flew a tight formation and the fighters didn’t bother us. The first attack from fighters came one and a half hours before we reached the target and continued until we were halfway home over the North Sea. Captain Barton flew the plane perfectly, continually dodging flak. We didn’t have a single hole in our plane. The bombing altitude was 26,500 feet, which was the highest thus far. It was a six-hour mission, and about four hours of it was under oxygen.”

The records of the Eighth Air Force noted that the Luftwaffe attempted air-to-air bombing with fighter aircraft and the use of parachute bombs fired by antiaircraft artillery.

Haugen hoped that the next mission would be an easy one. “We were scheduled to fly Captain Campbell’s plane as his compass was more accurate than ours, and as we were to lead the entire group, it was necessary to have an accurate one. However, after looking at the [aircraft’s] guns, our pilot, Captain Barton, refused to fly the plane.”

The mission progressed well until they became separated from the other groups in heavy overcast. Though unable to locate the other groups, they continued on to the target, the marshaling yards at Hamm. This was the first Eighth Air Force attack on a Ruhr industrial target.

The wing’s daily report indicated that the 303rd, 305th, and 306th Groups aborted while the 91st attacked the target. Some 75 enemy aircraft were reported to have made numerous “skilled and vigorous attacks.”

Haugen wrote, “We found the weather perfect over Germany and made a swell bombing run on the primary target. We fought off fighters on the way in, but it wasn’t until we were about 30 minutes from the target on the way back that the fireworks really began.

“The sky was full of fighters, and there were only 17 Fortresses to fight them off. We left with 20 planes, but two of them returned early with engine trouble and one went down over the target. In the battle that took place during the next 45 minutes, three more Fortresses went down including our left wing ship…. I had been out the night before with three of the fellows from the plane…. It was the second plane [that] our squadron has lost since we went into operations [on] November 7. Our plane returned without a single hole. I feel very fortunate to be back.”

Two days later, on March 6, Haugen and his crewmates found themselves as “Tail End Charlie” on a raid. Seventy-one B-17s of the 1st Bombardment Wing were dispatched against the power plant, bridge, and port area at Lorient, France. Three B-17s were lost.

Approaching from over the ocean, they took the defenders by surprise—the flak was light and only six fighters were encountered. “I saw the bombs hit, and it looked like a swell job of bombing,” Haugen said.

On March 8, a raid was launched at 10 am. On the way to the target—the marshaling yards at Rennes, France—the lead plane was forced to drop out of formation. Haugen’s B-17 was leading B Flight, so it took the lead for the second time in three raids. Haugen felt that for the first time the escort of RAF Spitfires had performed well. The raid was successful, and all the aircraft of the 91st returned safely, while other groups lost six aircraft to flak.

A raid on the rail yards at Amiens on March 13 was Haugen’s 15th mission. The weather was overcast, making bombing accuracy questionable. The operation was provided with heavy Spitfire cover, allowing 44 of the 80 B-17s that had been dispatched to hit the target and return safely.

Haugen wished for “10 more easy ones, and then go home.” But this was going to be difficult. On March 17, his plane was called back as they started across the Channel. The next day, trouble with the plane’s hydraulic system prevented takeoff. The following day there was a last-minute mission cancellation.

March 22 brought another raid to bomb the docks at Wilhelmshaven. The flak was heavy over the target, but there was little fighter opposition. After releasing their bomb load, the bomb bay doors were halfway closed when a flak round burst inside the bomb bay and sprung the doors, preventing them from closing. During a subsequent attack by a German fighter from beneath the plane, the ball-turret gunner did further damage to the doors, putting several holes in them, but they managed to return safely.

Haugen’s second mission to Paris occurred on April 4, but this was his first time there to drop bombs. The target: the Renault motor and armament works. No enemy fighters were encountered prior to the bombing. “It was a perfect day, and it really was a sightseeing trip. We could see the Channel from over Paris. The bombing was perfect.”

Another raid was made on the U-boat base at Lorient on April 16 by 83 B-17s. Flak was moderate and inaccurate, but the attack was hindered by a smoke screen and strong fighter opposition. Bombing accuracy was “fair,” and there were no casualties, as all aircraft returned safely.

Haugen noted, “When I rolled out of bed at 5:30, I knew that it was going to be a long, tough one, but it even exceeded my expectations. Our group and the 306th really took a beating. We were first over the target and were flying at 26,000 feet. The others were behind [us] and flying at 28,000 feet. The flak and fighters concentrated on us, and as a result, six planes from our group and 10 from the 306th were shot down. We returned with a few flak holes but were fortunate to escape further damage from fighters.”

All the planes lost were from the 401st Squadron. Roland Hale, a good friend of Haugen’s and a top turret operator in another Fortress, was killed. Hale’s plane had just a single .30-caliber hole in the aircraft, the only lingering trace of the round that hit Hale in the chest and punctured his heart.

The next raid struck the Focke-Wulf factory at Bremen, with 29 aircraft from the 91st Group and 73 from other groups. It was the Eighth Air Force’s largest mission to date. Flak was heavy and accurate, and a mass of fighters attacked during the bombing run. Of the 102 Fortresses, 16 were lost: six from the 91st and 10 from the 305th. Bombing results were considered excellent, even as an estimated 150 enemy fighters made the heaviest attacks to date.

Haugen was worried. “It was the most bombers we have ever lost, and we couldn’t stand to lose that many very often. The 401st had really taken a beating since they left the States. I believe it was the 12th crew to go down in their squadron.”

On April 30, Haugen received a seven-day furlough and headed for London. While there, he and three of his friends played tourist: sleeping in until noon each day, going to the movies, and visiting London Bridge, the Tower of London, and Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum.

Two weeks later, it was back to the deadly business of bombing the enemy. On May 13, Haugen’s unit was scheduled to hit the Avions Potez aircraft factory at Meaulte, France, between Lille and Paris. It was Haugen’s 21st mission. Bombing results were reported as good.

The next day, the group struck the U-boat yards at Kiel, Germany. Haugen’s B-17 was the highest in the formation and neither flak nor fighters bothered it.

The Eighth Air Force made a maximum effort as 154 B-17s, 21 B-24s, and 12 B-26s were dispatched against four targets: Kiel; the former Ford and General Motors plants at Antwerp, Belgium; the Courtrai Airfield, France; and the Velsen power station at Ijmuiden, the Netherlands.

The following day, May 15, Haugen was awakened at 3:30 am. His crew had been selected to lead the 91st and the other groups as well. The target was supposed to be the submarine construction yards at Wilhelmshaven, but due to overcast skies, they were forced to switch to the naval base and airdrome on Heligoland Island. Enemy opposition included approximately 100 Me-109s, Me-110s, FW-190s and Ju-88s, attacking in formations starting at 10:30 AM and continuing for 20 minutes. Fortunately, all the bombers managed to return.

A May 19 raid on the Deutsche Werke Kiel, A.G. at Kiel, Germany, was Haugen’s 25th mission, making him one of the first individuals in the squadron to reach that mark. His plane had a good position in the formation, the chief worry being flak. They were rocked by a few near misses, but they had no serious opposition, and returned safely.

“There’s nothing like finishing my tour on a tough mission to Germany,” he wrote. “There is naturally a certain amount of tenseness that goes with the last mission, and I don’t mind telling you it was good to leave the target area and start out over the North Sea knowing that you had now completed your active duty and had seen flak and fighters for the last time.”

Haugen recorded on May 21: “The Chief[Sly 2nd] took off for the first time without me in the radio room. After she left, I almost wished that I was along, as it sure was tough sweating them out…. The raid was to Wilhelmshaven, and again, it was a tough mission. The 324th lost three planes and among the crew members were five on their last mission.”

During the next couple of days, all but two of Haugen’s crewmates would complete their 25th mission. Haugen: “My only hope is that they can all see it through, and I know we will have a grand get-together after this war is over.”

The 91st Bomb Group (which had included the famous Memphis Belle) suffered the greatest number of losses of any heavy bomb group in World War II while flying its 340 bombing missions, earning two Distinguished Unit Citations in the process. Of the original 35 crews, 17 were lost in combat.

With his tour completed, Haugen hoped to be sent home or become an instructor, but he received orders to go on detached service to the 92nd Bomb Group to fly with a tow target detachment.

“Our pilot and co-pilot were from our squadron, so I didn’t mind too much flying,” he noted. “However, the idea of pulling a tow target for a bunch of shoe clerks, etc., to practice [shooting] on wasn’t exactly what I called a rest. It really turned out to be a snap, as we spent most of our time in town. We kept sweating out the boys that were still on operations.”

On June 7, 1943, Haugen was presented the Distinguished Flying Cross but turned down a commission, as he was anxious to return to the States. He departed England on July 3 aboard the Queen Mary,docking five and a half days later in New York.

After 36 days at home in Minnesota in the summer of 1943, Haugen reported to Salt Lake City for his next assignment: the 318th Squadron, 88th Bomb Group at Walla Walla, Washington. Transfers to Redmond, Oregon, and Avon Park, Florida, followed.

“I stayed there doing various jobs until September 1, 1944, at which time I decided to stretch my luck a little further and go back to combat.”

He returned with a handpicked crew made up entirely of former instructors and combat veterans. These included Lieutenant Peter E. Stene, Jr., whom Haugen considered an exceptional pilot; Lieutenant Branch, co-pilot and a former infantry officer; John J. Liana, bombardier; and Bill Welch, navigator.

The enlisted members of the crew included Mike Malone, top turret gunner and flight engineer, a veteran of 46 combat missions with the 97th Bomb Group in England and North Africa; Dick Schuttler, tail gunner, and a veteran of 25 missions with the 94th Bomb Group in England; and Commodore Bullard, Jr., the ball-turret gunner, a veteran of 50 missions with the 97th in Africa. George C. McMurtrey and Walt McCardel were the waist gunners. Haugen wrote, “We were out to beat the law of averages.”

Haugen’s break in combat service ran from May 19, 1943, to October 15, 1944, and much had changed during that year and a half. Long-range P-51 escort aircraft were now a common part of missions as the Eighth Air Force conducted daily strikes against multiple targets. Allied ground forces, having landed in France in June and July 1944, were driving across France and Belgium as bombers pounded away at the Reich.

Haugen and his crew’s new assignment was with the 571st Squadron, 390th Bomb Group based at Framlingham, Essex, which had been operating from England since August 1943. On October 15, they took off on their first mission as part of the 390th to “Flak City”: Cologne, Germany. The raid included a force of 754 bombers and 464 fighters to hit industrial, oil, and rail targets, bombing by PFF (Pathfinder Force) methods. It turned out to be an easy mission. The flight path took them along the Rhine, where some flak was encountered, a small piece passing through Haugen’s radio operator’s table.

On October 19, Haugen’s crew took on the role of weather ship. The crew was awakened at 3:30 am. They flew six and a half hours as they checked weather conditions to the target and operating altitudes and sent back information on cloud formations to be avoided.

This was the Eighth Air Force’s 683rd mission, this time dispatching 1,022 bombers and 753 fighters to hit the diesel engine and armored vehicle plant at Gustavsburg (at the junction of the Rhine and Main Rivers) and multiple secondary targets.

A larger formation—1,131 bombers with fighter escorts—were sent to Germany on October 22 to hit military vehicle plants at Hannover/Hanomag and Brunswick/Bussing, along with marshaling yards at Hamm and Münster. The takeoff of Haugen’s group was delayed until 10 am. His plane led the second element in the lead group, which was the first in the division over the target. There was no fighter opposition and flak was limited.

That day, they were carrying a new piece of equipment called “carpet,” which was supposed to throw off enemy radar and, consequently, their antiaircraft guns. Radio operators aboard the bombers also threw out chaff—strips of aluminum foil—to disrupt German radar. All the group’s planes returned safely from the strike.

On November 26, another raid on the marshaling yard at Hamm included 381 bombers with an escort of 132 P-51 Mustangs. Guided by radar, they made individual runs on the target. Because of the overcast, the results were not observed. Haugen’s Fortress, which had led the low squadron of their group during the raid, received only a few minor holes from flak.

Four days later, the target was Merseburg, which was not considered a milk run. Nearly 1,300 bombers and 1,000 fighters were dispatched to hit heavily defended synthetic oil plants and rail targets. Intense and accurate flak brought down 29 bombers.

“It wasn’t bad enough to be headed for such a rough target,” Haugen mused to his diary, “but it was delayed an extra hour to make it worse. Once again, we were leading the low group and things went okay until we were 67 miles from the target. At that time, we started to pick up flak, and it continued and got worse the closer we got to the target.

“When we reached the target area, the sky was black, and planes were going down all around us. About two minutes before ‘bombs away,’ they had our range, and while I was looking out the window at our wing ship, a barrage knocked the wing ship out of the sky. A piece came through the window and hit me in the face. About that time our group was really taking a beating.

“The lead [plane] of the lead [group] and his left wing ship were hit and ran together in the air and went down in flames. [Lieutenant] Branch was flying in that ship as formation control. The lead of the high [group] was hit and started to lose altitude with only two engines working. We continued on and released our bombs and sneaked out of the flak area to lick our wounds.

“At that time I advised [Lieutenant] Stene that I had been hit and Conroy gave me first aid. We also took a hit in the oxygen line on the opposite side of the radio room, so I had to throw Conroy a walk-around bottle. With the other two lead ships gone, the boys all joined on to us, that is, what was left. We counted 21 planes out of the 38 that took off on the mission.”

The final count for Haugen’s group was nine Fortresses lost. Upon return, Haugen was treated for a cut to his left cornea. His aircraft’s hydraulic system was also damaged, leaving only enough fluid to brake once or twice. As a result, they were the last to land. They had also been hit in a fuel tank, which caused them to leak fuel all the way back to base from the target.

On December 12, they were part of 461 bombers sent to hit the marshaling yards at Darmstadt, “a milk run.” There was no flak as they made a visual run on the target. The bombing was good, but being fifth in the bomber stream, there wasn’t much left to hit by the time they got there.

Only a few days later, the Germans launched Operation Watch on the Rhine—the Battle of the Bulge, which lasted from December 16, 1944, to January 25, 1945—the last major German offensive on the Western Front. On Christmas Eve, the 390th Bomb Group was sent to hit the airfield at Zellhausen east of Frankfurt as part of the effort to relieve pressure on American forces in the Bulge. The sky had finally cleared, allowing the Eighth Air Force to launch a maximum effort against enemy airfields and communications across western Germany. This was the largest air strike of the war, with 2,034 bombers and 853 fighters hitting numerous targets, including airfields at Darmstadt, Frankfurt-Rhein, Bilbis, Babenhausen, Zellhausen, and Gross Ostheim, along with marshaling yards at Pforzheim, Kaiserslautern, and Haildraum, and the Merzhausen air depot.

Haugen noted, “Maybe it was a morale factor for the boys in the Bulge, but we flew right down the middle of that 40-mile stretch. The target was an airfield that was the base for the planes that were giving our boys hell. We ran into plenty of flak flying down the Bulge and got banged up somewhat.

“However, we kept going, and when we were practically at the IP [Initial Point, where the bombs are released], the no. 2 engine started to run rough…. We had to reduce air speed to lessen the vibrating, and the rest of the boys couldn’t stay with us. Also, no. 3 was throwing oil all the way back to the horizontal stabilizer…. By this time, we had penetrated about 200 miles beyond the lines, and we had to cover all that distance alone without protection.”

On December 31, the entire Eighth Air Force was sent to hit both strategic and tactical targets in western Germany, encountering some 150 Luftwaffe fighters in the process, mostly in the Hamburg area. Twenty-seven bombers and 10 escort fighters were lost. Targets included the Wilhemsburg and Grassbruk refineries at Hamburg, the Misburg refinery, and the industrial area at Wenzendorf, as well as the marshaling yards at Neuss and Krefeld-Urdingen, the Kordel railroad at Ehrang, communications targets at Buzburg, Prum, and Blumenthal, and the Lutzweiler Bridge at Koblenz and the Remagen Bridge.

Haugen: “We bombed downwind and had a ground speed of 315 mph, but still the flak was finding the mark. I don’t think the Jerries wasted a single shell. About all we had left were four engines, as the rest of the plane was riddled. One close burst made several holes in the radio room. I was practically wrapped in flak suits, but still two pieces hit me in the left arm. One entered [my] elbow and another the forearm…. I remained in the hospital until January 15, and after returning to the base, got another flak leave of seven days.”

On January 28, 1945, Haugen wrote, “It looks like we will be flying quite often from now on, as there is a shortage of lead crews.”

On February 1, Haugen was surprised at how late that day’s mission got underway. They were leading the high group and were the first to get airborne at 11:45 am, on target at 3:15 PM, return to base at 5:10. Their target was a bridge at Wesel on the Rhine, but results were questionable.

A force of 699 B-17s and 328 P-51s were dispatched to hit rail targets and bridges in western Germany using Micro-H and H2X radar, hitting marshaling yards at Mannheim and Ludwigshafen, the highway and rail bridge at Mannheim, and the rail bridge at Wesel. No losses resulted.

A mission to Leipzig on February 17 was redirected to Frankfurt due to weather, shortening the operation by three hours. “We know definitely that we plastered the town, but just what we hit is a mystery.” A force of 895 bombers and 183 fighters had been dispatched to hit synthetic oil plants as well as the Frankfurt marshaling yard. Deteriorating weather forced the recall of 261 B-17s and 288 B-24s. The weather was so bad that several aircraft had to jettison their bomb loads during assembly. Unfortunately for Lieutenant Stene, who was flying his first mission as command pilot, his plane caught fire over the North Sea.

“Three men bailed out and then the plane went into a spin,” Haugen wrote. “There is practically no hope for Stene…. We’re still sweating, but have practically given up hope. His loss will really be felt.”

On February 22, operations switched from high-altitude to medium for a series of strikes. A total of 1,428 bombers and 862 fighters commenced Operation Clarion, a joint operation of the RAF and the U.S. Eighth, Ninth, and Fifteenth Air Forces to paralyze the already decimated German rail and road system. Most attacks were made visually, as bombing was conducted from just 10,000 to 12,000 feet to achieve maximum accuracy on targets without flak defenses.

Haugen noted, “We broke up into small groups and went after marshaling yards in small towns. It seems that all the large cities have been hit day after day, and consequently, Jerry was depending on passing most of his goods through the smaller towns…. We crossed the front lines at 20,000 feet and then let down to 17,500 to bomb. Some groups went in as low as 12,000 feet. There wasn’t a single burst of flak over the target. As a matter of fact, I didn’t see a burst all day…. We completely smothered the yards with bombs.”

Two days later, two groups were sent after the only important bridge still standing over the Rhine at Wesel. The target was well defended as the approaching aircraft encountered flak about 30 seconds before bomb release. Seventy B-17s hit the Wesel rail bridge, with 22 bombers suffering damage.

In his diary, Haugen wrote, “It was really accurate, bursting all around our plane. One piece came in over the bombardier’s head and hit the navigator, Lieutenant Welsh, in the right arm. The tail gunner had a narrow escape as a bit piece of flak missed his head by less than six inches. That piece knocked out the oxygen system on the right side from the radio room….

“One 1,000-pound [bomb] failed to release over the target, so we took it back to the base. When we landed, it jarred loose from the bomb bay and went through the doors. It went down the runway behind us and it was only a miracle that it didn’t go off. I believe we have learned our lesson and from now on we will drop all extra bombs in the North Sea.

“After a ‘flak leave’ of eight days and a couple of days extra to recuperate, we were once again after the Hun. We figured that a group lead was in the making…. As far as I am concerned, I hope we stay in that spot.”

Haugen’s group was part of a strike on March 18, 1945, as 1,329 bombers and 733 fighters were dispatched to hit targets in the Berlin area: the Schlesischer and Nord rail stations and the Tegel and Henningsdorf tank factories. The Luftwaffe made concentrated attacks on the bombers with their Me-262 jet fighters.

“It had been my desire to go to the big city and it finally came true…. Luckily, we had only a couple passes by jet jobs, and they didn’t hit anything but air…. We were in flak for about 12 minutes, and they really had our range. We sustained some battle damage…. One bomb hung up, and we had to drop it manually after we came off the target. The group lost three planes.”

On April 4, 1,431 bombers and 866 fighters were dispatched to hit airfields, a shipyard, and a U-boat construction yard at Kiel. Haugen’s Fortress again led the group, intending to make the bombing run using H2X radar, but a few seconds of breaks in the overcast were enough to allow them to plaster the target.

A week later, Haugen wrote, “Again, we led the group to the marshaling yards at Landshut.” Forty miles north of Munich, there was no flak, the weather perfect, as bombing was made from 17,800 feet. “The entire 8th went in the Munich area, and by the time we left, the entire area seemed to be burning.” More than 500 B-17s were sent to hit a munitions depot, airfields, and marshaling yards, 82 to hit the marshaling yard at Landshut.

Haugen’s 50th and final mission was flown on April 20, targeting the marshaling yards at Oranienburg, just north of Berlin. “We expected plenty of flak, as the target was in the outskirts of Berlin. However, it was like a sightseeing trip, as there wasn’t any enemy action along the entire route. We came back at low altitude and had the chance to view the ruins of Germany. Practically all the towns seem to be flattened.”

The April 20th mission was the Eighth Air Force’s 962nd; it included 837 bombers and 890 fighters, dispatched to hit rail targets north-northwest to south-southwest of Berlin, as well as in Bavaria and Czechoslovakia. Eighty-two B-17s targeted Oranienburg.

The Third Reich surrendered on May 8.

A second tour completed, Haugen would end the war with the Distinguished Flying Cross with Oak Leaf Cluster, Purple Heart with Oak Leaf Cluster, Air Medal with seven Oak Leaf Clusters, Presidential Unit Citation, Air Crew Badge, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with four bronze battle stars, World War II Victory Medal, and three overseas service bars. He was honorably discharged October 12, 1945.

After the war, Haugen coached and taught physical education at St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minnesota, from 1949 to 1951, then taught history and coached football at Logan High School in La Crosse, Wisconsin. Marshall B. Haugen, one of the very few bomber crewmen to survive 50 combat missions, passed away on December 13, 1998.