By David A. Norris

With two hours of daylight left, French Emperor Napoleon I saw his chance to make the Battle of Waterloo his greatest victory. After a day with many charges repulsed with great carnage, a critical bastion protecting the Duke of Wellington’s line had fallen to the French. On the French right, it looked like Prussian reinforcements had been pushed away from joining the enemy coalition forces. Wellington’s soldiers must be stretched nearly to the breaking point. It was time, thought the emperor of France, to hazard his most precious resource. He had so far withheld one of the finest corps of soldiers in European history, soldiers who were so valuable that one never wanted to risk losing one in battle. Now was the time to send in the infallible and legendary Imperial Guard.

This was the Napoleon Bonaparte’s second chance to bring Europe under the rule of one leader. His first regime had crumbled after disastrous defeats in Russia and the Iberian Peninsula. As armies from all over Europe converged on Paris, the emperor abdicated on April 6, 1814.

Louis XVIII, heir of the old Bourbon dynasty, was made the king of France. The former emperor was exiled to the little Mediterranean island of Elba. But, there would be a final act to the Age of Napoleon. On March 1, 1815, Napoleon escaped from Elba and headed for France. With him were 1,000 men of his old Imperial Guard, his “Elba Battalion,” who became the nucleus of a new army when he landed near Cannes to reclaim his throne.

As Napoleon headed toward Paris, royalist troops confronted him at Laffrey, a town near Grenoble in the French Alps. Louis XVIII’s soldiers were being sent to arrest the man who had held their allegiance only months before. Bonaparte faced them alone. Throwing open his coat, he said, “‘If any one wishes to kill his emperor, let him fire!” Rather than firing, the soldiers cheered Napoleon’s superbly timed dramatic gesture and joined his growing retinue.

Only 19 days after he stepped back onto French soil, Napoleon was in Paris and was again Napoleon I, Emperor of France. Immediately he took command of the army of France and set about raising more troops. Napoleon knew that his recent enemies would not quietly consent to his return to power.

Indeed, as news of the escape from Elba reached European capitals, the four largest European powers—Britain, Austria, Prussia, and Russia—each pledged 150,000 troops for the new war. For the first time the anti-Napoleonic coalition appointed a single general to command their combined forces: Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington. This Anglo-Irish soldier had won the grueling campaign that threw the French out of the Iberian Peninsula. In command of the Prussian contingent was Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blucher, the only general who had defeated Napoleon twice.

Austria and Russia needed time to mobilize their forces and bring them to the border of France. So in spring 1815, the French faced only two enemy armies. Both of them, under Wellington and Blucher, were in modern-day Belgium, then part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, not far from France’s northeastern borders.

Blucher commanded 120,000 men, but this figure included many conscripts and semi-trained militia. Wellington’s 68,000-man force, although often referred to as the “British” army, included only about 28,000 British soldiers. Much of Wellington’s force came from the smaller German states, and the rest were Belgian and Dutch soldiers who only one year before had been part of Napoleon’s army.

The Belgians and Dutch in Wellington’s army were commanded by 23-year-old Maj. Gen. Prince William of Orange. Diplomatic considerations insured that the prince received command of the largest corps of the Allied army. The duke’s other two corps were under Lt. Gens. Lord Rowland Hill and Sir Thomas Picton.

Napoleon was born in 1769, making him the same age as his adversary Wellington, but the passing years weighed more heavily on the emperor than they did on the duke. The emperor’s state of health in 1815 has been extensively debated in the two centuries’ worth of history books published after Waterloo. Certainly, he was no longer as active and vigorous as he had been in his thirties. Once, his officers marveled at his ability to work late into the night after long days and get by with short naps. Now, he grew tired more easily and needed longer hours of sleep. Even worse, health problems nagged at the emperor and crimped his mobility. Suffering from piles and a bladder infection, it was excruciatingly painful for him to spend long spells in the saddle.

Napoleon once kept tight control of his commanders. Unable to ride around a battlefield as freely as he once did, he would have to rely on his generals and his staff officers more than he was accustomed.

Compared to the conscript-heavy armies of his enemies, Napoleon’s army of 1815 had a high proportion of seasoned veterans. Some allied commanders led multinational forces, divided by language and different political loyalties. Practically all of Napoleon’s new army came from France. Highly motivated, the officers and soldiers were enthusiastic about adding another triumph to the long list of Napoleon’s brilliant victories.

The core of Napoleon’s revived army was a new incarnation of the elite Imperial Guard. Since 1804, the Guard had built a legendary reputation. Too valuable to risk except in desperate situations, it was always held in reserve until the outcome of a battle was hanging in the balance. Time after time, the Imperial Guard was sent into battle and changed a wavering situation into a smashing French victory. For the new Imperial Guard of 1815, foot soldiers with 12 years of experience joined the Old Guard. Others, all of whom had at least four years of military experience, joined the Young Guard.

Staffing the high command of the new Napoleonic army was difficult. Many brilliant officers who had served the French Empire well were dead or abroad. Others were reluctant to go to war for Napoleon once again. Napoleon would later regret some of the appointments he made among the generals willing to join him this last time.

Marshal Michel Ney was among the most famed of Napoleon’s commanders. The peak of his sterling service may have been his command of the rear guard during the grim wintertime retreat from Moscow in 1812. Bonaparte himself called Ney “the bravest of the brave.” His courage would never be questioned; if anything, he would burnish this aspect of his renown at Waterloo. Unhappily serving Louis XVIII, Ney embraced Napoleon instead of capturing him as the king had ordered. Napoleon would depend more heavily on Ney than ever before, effectively putting him in charge of the battlefield at Waterloo.

Marshal Jean-de-Dieu Soult had built a reputation as a battlefield general that lost much of its luster when he commanded the ill-fated French forces in the Peninsular War. Like Ney, Soult willingly switched allegiance from Louis XVIII to Napoleon when the chance came in 1815. In the new army, the old combat general was given the administrative post of chief of staff.

Marshal Emmanuel Grouchy, Marquis of Grouchy, was a rarity: a born aristocrat who held one of the highest commands in the Napoleonic armies. Grouchy’s previous service induced Napoleon to entrust him with the right wing of his army and to allow him more latitude than was wise.

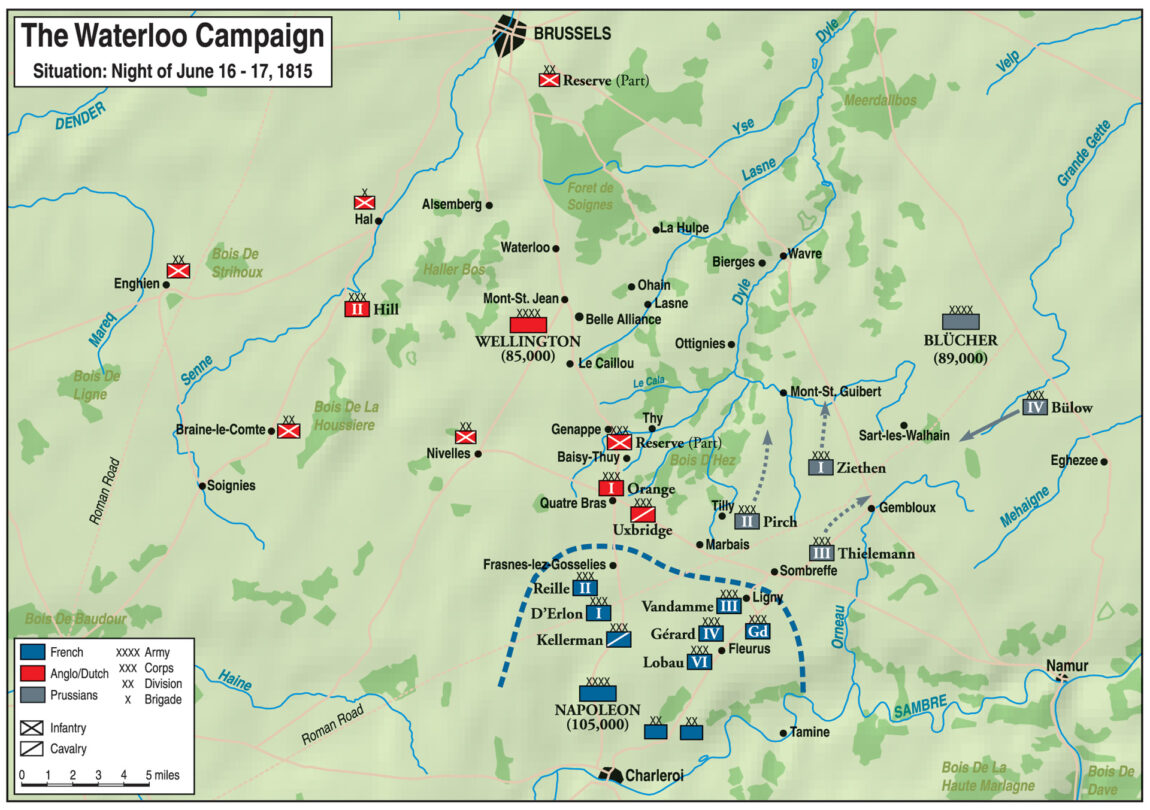

With Ney, Soult, Grouchy, and 120,000 men designated as the Armée du Nord, the emperor crossed the border from France to Belgium on June 14. They marched into the French-speaking region of Wallonia, heading first to Charleroi.

If the coalition combined its forces, it could quickly crush the emperor’s army. But Wellington’s men were dispersed around Brussels and to the south and west of the city. Blucher’s troops were sprawled from Charleroi to Liege, nearly 60 miles to the east. The emperor planned to slice between the two armies. Kept apart, the enemy forces could be defeated one at a time. Then, he could deal with the Austrians before the Russians could bring their numbers into the war.

After crossing the border, Napoleon risked splitting his army. He would lead the right column to attack Prussian troops encamped at Ligny. Ney and the left column would take a small crossroads hamlet called Quatre Bras, west of Ligny. Here, on the dividing line between the two allied forces, Ney could block Wellington from aiding Blucher. A lancer unit from Ney’s command rode to the crossroads. Finding no enemy troops, they rode on and left the place unoccupied. Ney otherwise did nothing to hold Quatre Bras.

So far, Napoleon’s moves had taken his enemies by surprise. On the night of June 15, as the French prepared for attacks on the next day, droves of allied officers took a break from their duties to attend a ball thrown by Duchess Charlotte of Richmond in Brussels. Rumors spread around the ballroom when Wellington arrived late. He quietly confirmed that the French were crossing the border. Officers flew to their commands, some of them not bothering to change. The next day, they would conduct the battle against the French still in their evening clothes and dancing shoes.

Two battles were fought on June 16. Each had a different outcome, and each played its part in leading to the final confrontation at Waterloo.

At Ligny, the French drove the Prussians from the field and captured 21 guns. Although no one knew it at the time, Ligny would be Napoleon’s last victory. West of Ligny, Dutch soldiers and Picton’s British division held off Ney at Quatre Bras, although the French assaults prevented Wellington from reinforcing Blucher.

The battles of June 16 showed that the Napoleon of 1815 had lost some of his earlier edge. Napoleon’s muddled orders to Ney did not explain that the main effort that day was to be against Ligny. With Ney’s attention focused on Quatre Bras, the potential rout of the Prussians at Ligny turned into an orderly withdrawal. After the battle, Napoleon was unusually relaxed and casual regarding the fleeing enemy, and vetoed an aggressive pursuit. Ten years before, he might have harried the fleeing army to its virtual annihilation.

Not only was Blucher allowed to escape, but the French failed to find out where he was going. On the morning of June 17, the French believed that the Prussian army was fatally mauled by the defeat, and they were sure that the Prussians would retreat east to Namur. Napoleon detached Grouchy with 33,000 troops to pursue Blucher’s army. But the Prussians were not heading for Namur. With good morale, they were marching north toward Wavre with every intention of carrying on the war. Aware of Blucher’s movements, Wellington abandoned his plans to concentrate for battle at Quatre Bras. Instead, he fell back up the Charleroi-Brussels road (roughly parallel with Blucher’s route) to Waterloo, a village about 12 miles south of Brussels and nine miles west of Wavre.

Around Waterloo, broad farm fields and gently rolling countryside offered ample room for the armies to maneuver. Two miles south of the village of Waterloo, the Charleroi-Brussels road crossed a ridge called Mont St. Jean. Here, Wellington arranged his 68,000 men and 156 guns along the high ground, facing to the south. On the southern slopes of the ridge were three clusters of farm buildings, called Hougoumont, La Haye Sainte, and Papelotte. These three farmsteads, with their manor houses, masonry walls, and brick buildings, were wonderfully suited as fortified defenses.

Rain was falling late on the afternoon of June 17 as Napoleon’s 72,000 men, who had 256 guns to support them, neared Waterloo from the south. They halted along the road, near a tavern called La Belle Alliance. The tavern was atop a low ridge roughly parallel to Mont St. Jean, and here the French set up camp in preparation for the battle that would come the next day.

The precipitation swelled into a downpour. Among the English, Sergeant William Lawrence of the 40th Regiment of Foot recalled, “That night we crept into any hole we could find, cowsheds, cart-houses, and all kinds of farmstead buildings, for shelter.” Lawrence could “never remember a worse night in all the Peninsular war, for the rain descended in torrents, mixed with fearful thunder and lightning, and seeming to foretell the fate of the following morning.”

Napoleon spent the evening at Caillou, a farmhouse south of the inn. He slept for a few hours, then rode out about 1 am for perhaps two hours to inspect his lines. In the distance glowed campfires that allied soldiers managed to nurture in the rain.

The next day was Sunday, June 18, 1815. About 8 am, the rain started tapering off. With some of his staff officers and commanders, the emperor reigned over a breakfast at Caillou. They ate from silver plate emblazoned with the imperial arms. Bonaparte seemed serenely confident to his staff. “We have ninety chances in our favor, and not ten against us,” he said. The night before, Soult broached the question of summoning all or part of Grouchy’s forces to strengthen their lines. Napoleon snapped, “Because you have been beaten by Wellington, you consider him a great general. But, I tell you that he is a bad general. And now I tell you that Wellington is a bad general, that the English are bad troops, and that this affair is nothing more serious than eating one’s breakfast.”

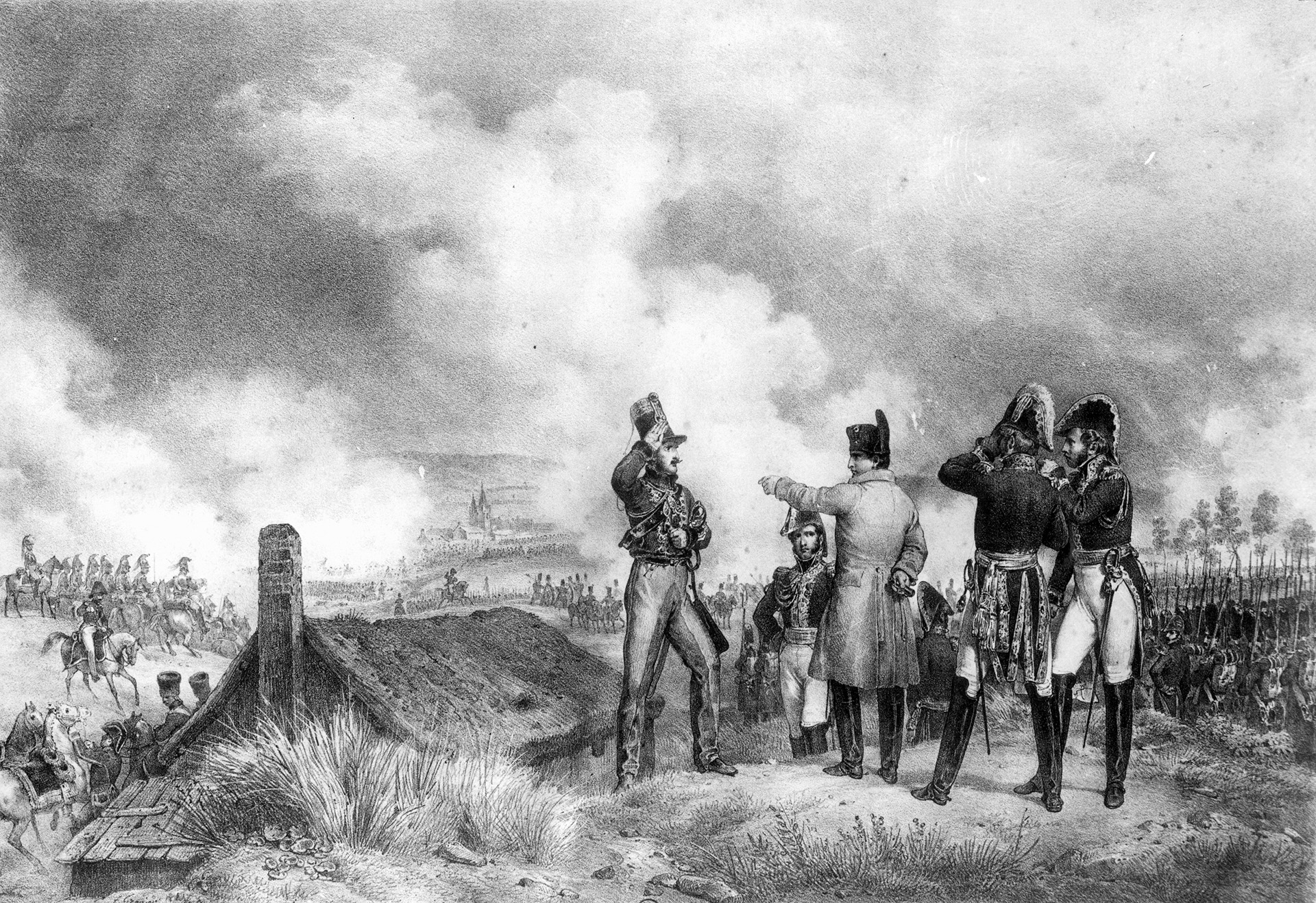

After the rain stopped, Napoleon reviewed his lines from horseback as the armies arrayed for battle. Bands played as the French troops in their resplendent uniforms cheered, “Vive l’Empereur!” Ensign Rees Gronow, an officer of the 1st Foot Guard, who was on duty as an aide-de-camp, plainly saw the emperor as he rode with his staff during the spectacular French review from the allied line. British officers near Gronow, watching their famous adversary through a spyglass, saw him in the distance on his white horse reviewing his vast host.

Perhaps a little surprisingly for one of Europe’s wiliest tacticians, Napoleon’s battle plan at Waterloo was straightforward and simple. He would open with a diversionary attack from his left, with elements of Lt. Gen. Count Honore Charles Reille’s corps moving against Hougoumont. Then, a heavy bombardment would pummel the allied center and left. When the enemy was sufficiently weakened by the artillery, the French would launch an all-out frontal attack on Wellington’s center.

Napoleon was aware that substantial numbers of Prussian troops might reach Wellington at Mont St. Jean that day. Not so many years ago, the combative campaigner would have launched his attacks immediately after first light, hoping to overrun the enemy before they could be reinforced. And this was likely what Napoleon had in mind. However, the night of soaking rain worried many officers among his staff and his top generals. Muddy ground would slow the infantry, and would also impede the cavalry, which Napoleon expected to help shatter the enemy lines. Field guns would be difficult to move in the soft ground. Furthermore, many of the troops were tired from marching well into the night to reach La Belle Alliance. Considering it prudent to allow the ground to dry out a bit, the emperor delayed the first infantry attacks for a few hours.

Wellington used the delay caused by the rain to arrange his lines. Assured by 3:30 am that Blucher was sending troops to his aid, the commander was prepared to hold on to the ridge. His heaviest concentration was along his right, fronted by Hougoumont. Using one of his familiar tactics, the duke deployed many of his troops lying down behind the crest of the ridge. This would partially shield them from some of the enemy artillery’s preliminary barrages, and would also limit French knowledge of the placement and numbers of his men. The allied left around Papelotte was more lightly manned, in the expectation that the Prussians would arrive on that side of the battle line.

There was one very unfortunate error in the duke’s troop deployments. To prevent a surprise move against his right, and to cover a possible retreat if things went badly, he sent 17,000 troops roughly eight miles northwest to the villages of Halle and Tubize. With the potential of the Prussians coming in on Wellington’s left, a long swing to the right by the French would have been highly unlikely. Added to his 68,000 troops, the men sent toward Tubize would have strongly bolstered Wellington’s numbers.

Obtaining some relief by getting out of the saddle, Napoleon settled in to direct the battle on foot. His headquarters was a table dragged out of a farmhouse onto a little knoll. Aided by a spyglass, he had a view of part of the battlefield, and maps and papers were spread out on the table before him. Mounted couriers and staff officers awaited his orders.

Also on hand were local guides. One fellow, a local innkeeper named Jean Decoster, had been pulled out of bed at 5 am to furnish the French with his local knowledge. Another guide, Joseph Bourgeois, was so frightened that he stuttered whenever called upon, and he kept his eyes fixed on the ground. Eventually, Napoleon dismissed him. Asked later what it was like being in the presence of Napoleon, Bourgeois said, “If his face had been the face of a clock, nobody would have dared look at it, for the hour.”

By the late morning, the French knew that Blucher had moved to Wavre. About 10 am, Napoleon ordered Grouchy to attack the Prussians.

As the sun came out to dry the landscape, a steady breeze blew, the kind that huntsman called “a drying wind.” By 11 am, the ground was dry enough for the French to open the battle. Napoleon’s artillery opened fire to cover the start of the first infantry advance. On the French left, Prince Jerome Bonaparte’s (the emperor’s brother and the recent king of the Netherlands) division of Reille’s corps drew the task of taking Hougoumont.

Hougoumont was held by troops from Britain and the German state of Nassau. Some defenders punched holes in the brick walls to create loopholes for their muskets. Other defenders took advantage of hedges and orchards around the buildings. Although intended as a diversion, Reille’s attack on Hougoumont grew into a major effort. As the defenders held on, more and more French units were thrown in. Their absence would be felt when Ney launched his main attack later with a lighter force than intended.

Beyond the north gate of Hougoumont, a party of French sapeurs gathered to try to force their way inside. Leading the assault was a sous-lieutenant named Legros, whose first name does not appear in accounts of the battle. Once attached to a unit of engineers, the powerful Legros was nicknamed L’Enforceur. With an axe as his chosen weapon, Legros broke open the gate and his 30 men poured into the courtyard. As the French rushed in, the defenders nearest the gate were pushed back. If Legros could hold on long enough for more French to reach him, the anchor of Wellington’s right would fall.

Lieutenant Colonel James Macdonnell, commander of the Hougoumont detachment, called for help in getting the gate closed. About 10 officers and men joined him, among them Lt. Col. Henry Wyndham and Corporal James Graham. They rushed to the gates, slammed them shut again, and then brought down the wooden bar to hold them fast.

While shutting the gate Wyndham saw a French grenadier, supported on the shoulders of another man, peer over the wall and aim at him with a musket. Graham and the Frenchman fired at the same instant. The grenadier missed, and Graham killed him, saving Wyndham’s life.

Any French reinforcements were now locked out, and Legros and his 30 soldiers were trapped inside. Every one of the storming party was killed except for a young drummer boy. Wellington later said that the fate of the battle turned on the gates of Hougoumont.

Wyndham, it was said, was so affected by the fighting at the gate of Hougoumont that he could not bear to close a door. Years later his niece remembered his suffering from sharp winter draughts roaring through an open door.

As the duke awaited Blucher, the emperor anticipated Grouchy’s arrival. Grouchy heard the French artillery from late morning on. He was summoned to Waterloo in two rather ambiguously worded dispatches drafted by Soult at 10 am and 1 pm. Wary of disobeying the emperor’s previous orders in favor of new, contradictory dispatches, he decided against turning around to march toward the sound of the guns.

Blucher had maneuvered past Grouchy and dispatched the corps of Field Marshal Count Hans von Zieten and General of Infantry Count Bulow von Dennewitz to join Wellington. Ominous news struck the French at noon when a Prussian hussar was captured at Saint-Lambert, only three miles to Napoleon’s right. General of Division Georges Mouton, Count de Lobau, was sent with his VI Corps to the village of Placenoit to protect the French right and block the first units of the Prussian army that approached the battlefield.

By 1 pm, the French were ready to start their main offensive of the day. Gunners increased their rate of fire, aiming at Mont St. Jean. Wellington ordered his men to lie down beyond the crest of the ridge to shelter them from the heavy bombardment. Maj. Gen. Willem Frederik Bylandt’s Dutch-Belgian brigade, in the open, was heavily pounded by the artillery. At 1:30 pm, the 17,000-man corps of General of Division Jean-Baptiste Drouet, Count d’Erlon, moved toward the allied line atop Mont St. Jean. Originally, d’Erlon was to be supported by Lobau before the latter’s corps was sent to the right flank.

D’Erlon’s four tightly packed divisions moved en echelon. They were crowded together to avoid La Haye Sainte on their left, which was held by Major Georg Baring of the King’s German Infantry. As the French divisions marched up the hill, their own artillery had to cease their covering fire. Bylandt’s brigade wavered and broke, but d’Erlon came under heavy flanking fire from La Haye Sainte, a nearby sandpit manned by the 95th Rifles and allied artillery.

Behind the crest of Mont St. Jean, the soldiers of Lt. Gen. Sir Thomas Picton’s division could not see the advancing French. They did see Bylandt’s men fleeing past to the rear. Some allied gunners in front of Picton abandoned their pieces and ran as well. As the French reached the crest, Picton ordered, “Up! At them!” Three thousand British soldiers, until then hidden from the French, suddenly arose. In response to a wobbly French volley, they poured a devastating fire into the French column at a distance of perhaps 50 yards. Then, with fixed bayonets, they charged. As the redcoats rushed forward, Picton was killed instantly by a shot in the head.

Adding to the surprise of the French on Mont St. Jean, more than 2,000 British cavalrymen galloped into focus amid the battle smoke. The Household Brigade and Maj. Gen. Sir William Ponsonby’s Union Brigade (so called from its composition of English, Scots, and Irish horsemen) hurled themselves into the French infantry and some accompanying cuirassiers. The French were pushed off the ridge with the loss of 2,000 prisoners and two regimental eagles.

Buoyed by their success, and with no time for a complete battle plan, the British cavalry roared down the slope and continued up the ridge near La Belle Alliance. With their commander, Lt. Gen. Henry Paget, Earl of Uxbridge, riding at their head, the horsemen hacked their way through and over some of the French batteries in front of the main line. Losing momentum, and with their horses blown, Uxbridge’s cavalry was hit by a devastating counterattack by French cuirassiers and lancers. About half of the British were killed or taken prisoner; Ponsonby was killed by an enemy lance.

Action in the center slowed for a time. Toward Hougoumont, French howitzers fired carcass ammunition, incendiary shells that set the thatched roofs of the farm complex afire. Flames swept through the buildings, trapping wounded soldiers inside. But Macdonnell and his men kept up their fire and clung to their position.

The previous night’s rain, which had impeded the French, also slowed the Prussian advance. Their route from Wavre took them across swollen streams and muddy ground that each successive wave of troops churned into a deeper and stickier obstacle. About 4 pm the Prussian IV Corps approached the French right flank, where Lobau managed to blunt their advance.

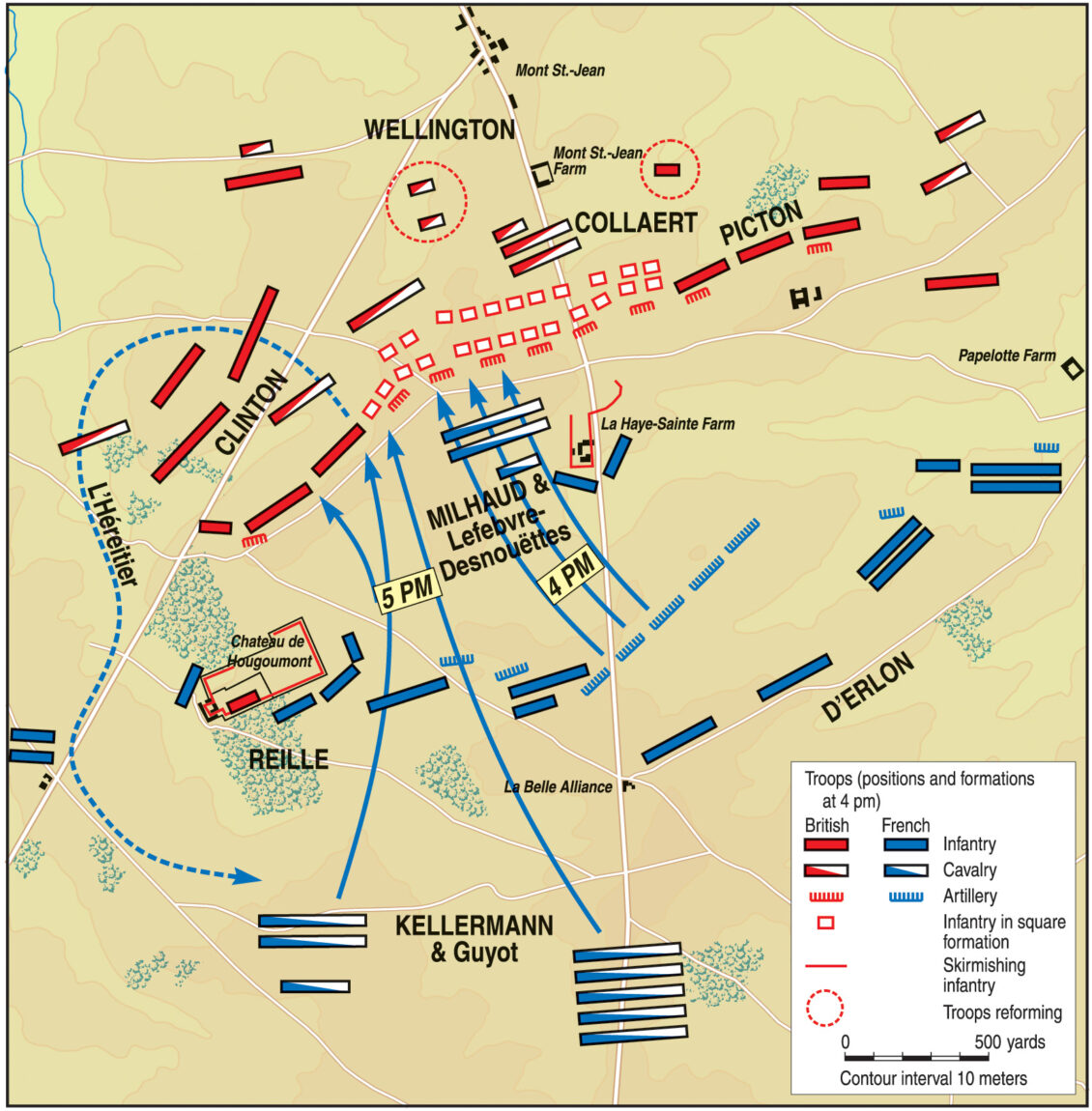

As the pressure from the Prussians increased on the French right, Ney mistook some shuffling of Wellington’s units for the beginning of a general retreat. Ney ordered the cavalry corps of General of Division Count Edouard Jean Baptiste Milhaud to charge up the slope of Mont St. Jean. Trying to break veteran infantry with cavalry unsupported by infantry was a risky gamble. But Ney was confident, and “the bravest of the brave” joined Milhaud to lead the charge himself.

Rather than preparing a retreat, Wellington was reinforcing his center by throwing in some of his reserves. As his artillery pounded the advancing French cavalry, his British and German foot soldiers formed into squares to repel Ney’s charge.

Ney took the cavalry by a different route than the earlier attacks of d’Erlot. Now, the new French assault came west of the Charleroi road, aiming at Wellington’s line between La Haye Sainte and Hougoumont.

The slopes of Mont St. Jean rise at a gentle angle. But, the farm fields were still damp, and their muddy soil made the long ride uphill even slower and more exhausting for the French horsemen. The cavalry was squeezed together to minimize fire on their flanks as they passed between La Haye Sainte on their right and Hougoumont on the left. So tightly packed were the French riders that some of their horses were lifted completely off the ground and carried along with the rushing tide of cavalry.

At last, the thousands of French riders neared the allied guns. Wellington’s gunners fired their last rounds. Under orders, they fled from their pieces to take refuge in the infantry squares. French lancers, cuirassiers, and other cavalry galloped through the silent guns and flung themselves at the infantry.

Formed in a square, infantry of the era were almost invulnerable. The hollow rectilinear formations might have as many as four ranks. The two rear ranks poured steady musket fire. The front rank kneeled, putting their musket butts on the ground and holding them out diagonally while the second rank held their own their muskets and bayonets out at waist level. In effect, the square presented a steel-tipped chevaux-de-frise with two ranks of soldiers firing behind it.

A square was vulnerable to heavy small-arms fire, of course, and well-placed artillery could plow through its closely aligned ranks. But, if the men held steady and did not panic, they were likely to shoot down enough of the attacking cavalrymen to repel a mounted attack.

Added to the allied infantry squares, Wellington’s remaining cavalry pitched into Ney’s horsemen. Under the pressure, Ney withdrew. Unfortunately for the French, no one had thought of bringing tools to spike the allied cannons. The gun crews ran out from inside the infantry squares and fired at the retreating cavalry. Once withdrawn, Ney halted the horsemen and turned them around for another attack.

From La Belle Alliance, Napoleon could see the wave of French horsemen ebb and flow against the enemy line. The emperor gloomily told Soult, “This movement is premature and may yet have disastrous results.” Yet, there seemed nothing to do but support Ney. Under Napoleon’s orders, the cavalry corps of General of Division Count François Etienne Kellermann was committed.

As the battle grew more desperate, Napoleon returned to the saddle. When the very nervous innkeeper Jean Decoster accompanied the emperor, the guide was secured by having his saddle tied to that of a chasseur. As they got closer to the enemy, Decoster constantly ducked and swerved to avoid bullets. Napoleon paused in his direction of the battle to tell him, “Now, my friend, do not be so restless. A musket-shot may kill you just as well from behind as from the front, and will make a much worse wound.”

Whenever the French cavalry charges receded, allied foot soldiers came under renewed tempests of French artillery. Gronow was inside an infantry square that by late afternoon resembled “a perfect hospital, being full of dead, dying, and mutilated soldiers.” Fearsome as the cavalry charges were, Gronow found the mounted attacks to be a relief because they made the enemy artillery cease fire.

As thousands of Kellerman’s and Milhaud’s cuirassiers drew nearer, Gronow later recalled “the very earth shook under the enormous mass of men and horses.” Amid the tumult the ensign noticed an odd sensation. “I shall never forget,” he wrote, “the strange noise our bullets made against the breastplates” of the armored cuirassiers, which sounded like “the noise of a violent hailstorm beating against panes of glass.”

In the smoke, chaos, and death looming over the battle, it is uncertain how many times the French cavalry charged up Mont St. Jean. But it was not enough. Wellington’s squares blasted and hurled back each mounted attack.

With the Prussians looming over his right, Napoleon held his infantry reserves in place instead of throwing them into Ney’s attacks. About 6 pm Ney ordered another assault on the enemy center, while Bonaparte at last pulled the Imperial Guard out of reserve. But the guards were sent to bolster Lobau.

“Every moment was a crisis,” wrote Brigade-Major Harry Smith, a participant in the battle. By 6:30 pm, Wellington faced an even greater crisis than he had seen that day, and the tide of battle seemed to be turning toward the French. Lobau pushed the Prussians back from Placenoit. Its defenders nearly out of ammunition, La Haye Sainte finally fell to the French. The French could now bring artillery up much closer to the enemy. At that point, Napoleon felt that his right flank was safe and that it was time for a final stroke to break Wellington’s line. Napoleon released most of the Imperial Guard to reinforce Ney.

Just as the guardsmen prepared to move on Mont St. Jean, Wellington’s battered and frayed center was at last getting a little relief. After the nerve-wracking tension of the day, the arrival of elements of the Prussian I Corps let Wellington tighten his thinning lines. Wellington personally brought up some Brunswick troops, his remaining reserves.

Fifteen minutes after the first Prussians joined Wellington, at 7 pm, the battalions of the Imperial Guard swept forward led by Ney. They marched up the slope, roughly following the route taken for the futile cavalry attacks, aiming at Wellington’s line between the captured La Haye Sainte and the still defiant Hougoumont. To the right, the Imperial Guard was supported by d’Erlot’s corps, and elsewhere Reille and Lobau kept up their fire.

To steady his soldiers against the rumors sweeping through the ranks about Prussian reinforcements, Napoleon spread false reports that Grouchy had reached the field with his 33,000 men.

Battle smoke partly hid the massing of the Imperial Guard for their last-ditch attempt. A French captain deserted to the allies, bringing news of the impending charge of the Guards. Wellington ordered his guns to cease fire on the La Haye Sainte batteries and other French artillery to save their fire for the impending infantry attacks.

Pressing toward the enemy, the Imperial Guard advanced in squares. Between each square were two 8-inch guns of the horse artillery. Allied guns sliced into the Guards’ squares, and the survivors adjusted to fill the gaps. Ney’s horse was killed. It was the fifth horse shot from under him that day. At some point in the fighting that day, an enemy saber sliced off one of Ney’s epaulets.

When Ney and the cream of Napoleon’s army neared the ridge, its right echelon scattered the Brunswick troops and two English brigades. Then, allied artillery staggered the Imperial Guard, and Colonel H. Detmers’ Dutch-Belgian brigade charged at them with bayonets. Detmers and the guns sent this section of the Imperial Guard reeling back down the hill.

In the center, Maj. Gen. Peregrine Maitland’s brigade had been lying down awaiting orders. With them, Gronow heard Wellington shout, “Guards, get up and charge!” At the order, Maitland’s men fired a crushing volley into the French “and rushed on with fixed bayonets and the hearty Hurrah! peculiar to British troops,” wrote Gronow.

All along its front, the Imperial Guard stalled. The elite Guard wavered and then began retreating. As the flood of French troops ebbed, the cry went up throughout the French lines, “Le Garde recule! (“the Guard is retreating”).

That morning, the French line had been roughly straight and parallel with Wellington. But at the climax of the battle, as more and more Prussians pressed against Napoleon’s right, the French line was bent south at a right angle in front of Papelotte. Zeiten’s Prussians hit the French right, which began to break about 7:30 pm. Seeing his forces advancing and the fearsome Imperial Guard in retreat, Wellington said, “In for a penny, in for a pound,” and ordered a counterattack.

Panic engulfed the rest of Napoleon’s troops, who knew the Imperial Guard had been shattered and saw the growing avalanche of allied soldiers nearing them. Most of the French regiments crumbled and fled from the field.

Lieutenant Colonel Henry Wyndham opened the door of a halted carriage and climbed in. At the same moment, Jerome Bonaparte spilled out of the other door and escaped. The emperor himself abandoned the field. Left behind on the battleground of Waterloo were 25,000 French dead and wounded. Another 9,000 were scooped up as prisoners. Allied losses all told ran to about 23,000.

Although Grouchy attacked and defeated part of the Prussian army at Wavre on June 19, Napoleon’s Armee du Nord was smashed beyond repair. Napoleon went back to Paris. He tried to hold on to power, but only his most loyal (or delusional) adherents thought there was any chance to prolong the emperor’s reign. With nothing left to stop the allied forces converging on him, Emperor Napoleon I abdicated again on June 22. Louis XVIII was reinstalled as king of France, marking the close of the Napoleonic Era. The brief final flare of the Napoleonic Empire, which was crushed by the defeat at Waterloo, would become known as the Hundred Days.

Napoleon tried to escape to the United States, but he fell into the hands of the Royal Navy. A more secure place of exile was selected for the former emperor: the remote British colony of St. Helena, an island in the South Atlantic. There was no chance of escape from one of the British Empire’s most isolated possessions.

Napoleon Bonaparte had six years to reflect on Waterloo before he died on St. Helena in 1821. He blamed his marshals and generals, especially Ney. He complained about the poor caliber of his staff officers and even the entire army. Once, Napoleon told his companion Gaspard Gourgaud, “The men of 1815 were not the men of 1792. My generals were faint-hearted.” Perhaps, thought the exile, waiting one more month before beginning the offensive would have given the army more time to solidify itself. Another time, he complained, “Ah! Mon Dieu! Perhaps the rain on the 17th of June had more to do than people think of the loss of the Battle of Waterloo.”

Repudiating talk of revolution and reform, the Congress of Vienna restored the old system of monarchial rule. For Europe, Waterloo marked the start of an unprecedented 99 years of relative peace. There would be some small wars; revolutions in 1848, the Crimean War, and wars leading to the unifications of Italy and Germany. But, no conflicts drew the entire continent into all-out war until the 1914 assassinations of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and the Duchess Sophia of Austria-Hungary at Sarajevo led to World War I. Charleroi, so close to Waterloo, was the site of fighting early in this new world war in September 1914. But the fighting at Charleroi would lack the tone and character of the grand clash at Waterloo fought between Napoleon and Wellington on that long summer day in 1815.

Good article, nice maps. Thanks.