By Chris Marks

Lieutenant Hollis Hills had every reason to be puzzled. His guns had just raked the Japanese fighter ahead of him, the rounds striking home along the enemy’s fuselage and wing roots. But the Japanese plane attempted no evasive maneuvers—no chandelles, wingovers, or rolls. It just kept going, and that was the puzzling part. Hills pulled up next to his quarry and looked over. The pilot’s head had been practically shot off, his hands locked in a death grip on the controls. The Zeke began a gentle turn toward the sea. The morning of April 29, 1944, was a bad time to be one of the Emperor’s pilots over Truk atoll.

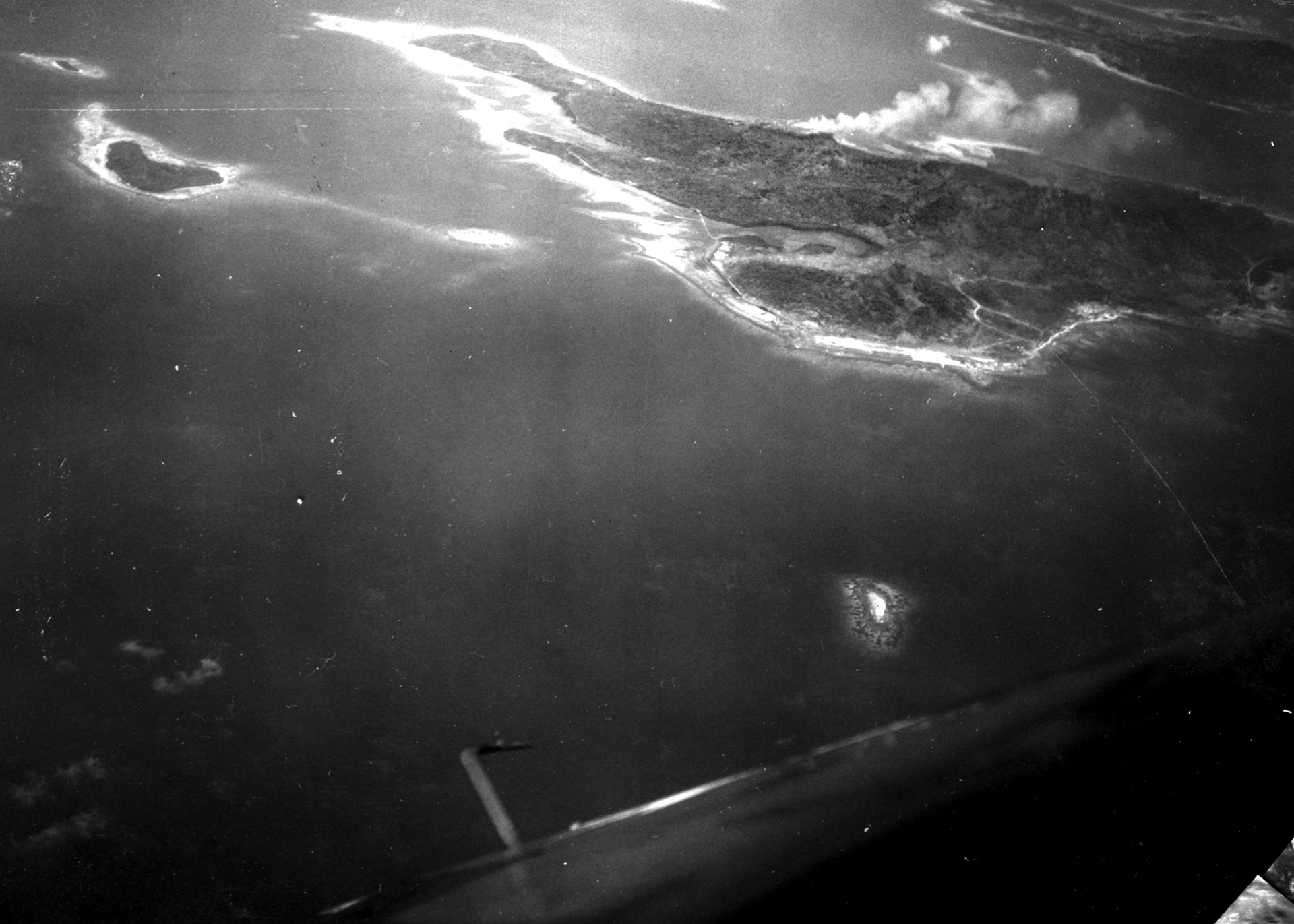

Situated just above the equator in the Caroline Islands, Japan took possession of Truk’s magnificent anchorage after World War I. As Japan’s ambitions advanced outward across the Pacific, it became a vital base for her Combined Fleet. Little was known about the atoll, and the term “Gibraltar of the Pacific” came into use—often prefaced by “bastion” and “impregnable.” Suspicions grew into fears.

But the American admirals commanding the Pacific Fleet were not governed by fear. Enabled by the tireless work of sailors, fighting Marines, and stateside shipyards, they stood ready to deliver a severe blow to Imperial Japan in early 1944.

When two American B-24 Liberators on a long-range reconnaissance mission over Truk were detected on February 4, Japanese Admiral Mineichi Koga realized he had a problem: American airpower was within striking distance of the Combined Fleet’s forward base. The vastness of the Pacific no longer protected Truk. He ordered his capital ships out of harm’s way, almost 1,200 miles west to the Palau area. They would never return.

At dawn on February 17, planes from Admiral Marc “Pete” Mitscher’s Task Force 58 launched a relentless two-day assault on Truk named Operation Hailstone. Although the big targets were long gone, the Americans found plenty to shoot down, blow up, or sink. In the process they also created the finest wreck diving site in the world. No longer useful as a naval base, Truk wasn’t worth a Marine invasion. But it could not be ignored.

In late April, Mitscher took another swipe at the once-fearsome atoll. Fresh from assisting General Douglas MacArthur’s forces in New Guinea and headed for replenishment at Majuro, TF 58 made an immense detour to Truk. This time, one of the carriers at Mitscher’s disposal was the USS Langley. During Hailstone her task group had been ordered to support the invasion of Eniwetok.

The Langley was a “light” carrier of the new Independence class (CVL)—an effort to quickly strengthen American carrier forces after early war losses. The naval architects slapped down a reduced carrier deck on the hull of a cruiser. Langley’s skipper was Captain Wallace M. “Gotch” Dillon, an Annapolis wrestler described in his 1918 yearbook as “a handy man to have around in a rough-house.” An early naval aviator, he shared a bungalow on Coronado in the 30’s with his good friend “Jocko” Clark. Dillon was a firm yet approachable officer, widely respected by his crew. He returned their respect.

Langley carried the aerial warriors of Carrier Air Group 32 into battle against Japan. Because of the reduced hangar and deck space, AG 32 consisted of just 23 Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters and 9 TBF/M Avenger torpedo bombers. But what the squadron lacked in numbers was more than offset by the aggressive spirit of her fighter section commander.

Fighting 32 was led by Lieutenant Commander Edward Cobb Outlaw of Goldsboro, North Carolina. His 1935 Annapolis yearbook defined “Eddie” as a “social lion” with “plenty of personality.” After graduating near the bottom of his class—436 out of 442—he blossomed into a determined and widely respected naval aviator. The sailors in the Langley’s photo department knew him as “Shoutlaw”—they never managed to develop fighter-gun camera film fast enough to suit him.

Outlaw’s wingman was a cheeky 23-year-old Lt. (j.g.) named Donald “Dagwood” Reeves from Pueblo, Colorado. Seeing a bit of his mischievous self in the young reservist, Outlaw took him under his wing. He credited Reeves with “considerable initiative” in a fitness report, noting that he “inspired his fellow pilots by his enthusiasm and excellent performance.” Reeves was a popular character in the unit, especially after successfully asking the Walt Disney studio to design the squadron patch for VF 32.

Reflecting their commander’s aggressive tone, the pilots of “Outlaw’s Bandits” had sharp elbows, vigorous affections for nurses and strong drink, and low regard for apologies. They were fighter pilots. But above all else, the young men harbored a burning desire to be unleashed against the Japanese. On April 29, they got their chance.

In the pre-dawn darkness 90 miles south of Truk, Outlaw and Reeves took off from the Langley in a rainstorm. Next in line, leading the second section in Outlaw’s division, was another 23-year-old Lieutenant (j.g.), Richard H. May from Seattle. A licensed pilot for six years, May had flown with VF 10 on Enterprise in his first Pacific tour. He loved the sound of the big Pratt and Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp engine, calling it “a most fortunate mating of engine to airframe.” Having no interest in getting drenched and then shivering at altitude, May closed and locked his cockpit hatch—a violation of VF 32’s launch procedures. He watched “the exhaust stack flames of Outlaw and Reeves disappear into the blackness” and then it was his turn. He was followed by his wingman, Ensign John A. Pond of Memphis, whose initials transmuted into a nickname he disliked.

The second Langley division was led by Lieutenant Hollis Hills of Pasadena. Determined to get into the war against Hitler, “Holly” enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1940 and shot down a German FW-190 over Dieppe, August 19, 1942. At 29, he was among the oldest pilots in the squadron. His wingman was Lieutenant (j.g.) Lloyd McEachern of Wellsville, New York.

The last Langley section into the air was led by Lieutenant (j.g.) Harry McClaugherty of Narrows, Virginia. Owing to his solid build his natural nickname was “The Bear.” It was stenciled across the Mae West life jacket he wore in flight. His wingman was Lieutenant (j.g.) Ralph Schulze of Waco, Texas.

“We rendezvoused over the ship about an hour before dawn and proceeded in to the target, climbing to an altitude of 10,000 feet,” Outlaw said in an interview decades later. Fifty miles from the fleet he paused and waited for fighters from Lexington and Enterprise to join up for a coordinated sweep. Precious minutes passed, and Outlaw grew concerned. He desired to arrive over the atoll at daybreak, when they “would have just enough light to see the enemy through illuminated gun sights.” Admiral Clark once wrote that “in the game of war an advantage unpressed may have tragic consequences.” Eddie Outlaw wanted every advantage for himself and his men. He made the call, and the Hellcats resumed their northward course alone. Each man was surely apprehensive about what lay ahead. Fighting 32’s after-action report picked up the story.

“Upon reaching the central section of the lagoon the planes orbited for about three minutes. There were no other US Naval VF planes in the area.”

Lieutenant Hills spotted “a formation of planes some eight miles to the west at an altitude of about 6,000 feet flying eastward” toward the Langley fighters. Outlaw didn’t hesitate, leading his men straight toward the unidentified group. “The planes were flying in fairly close 3-plane Vee formations, each in line astern,” the report continued. “At just about the time the planes were identified as enemy, the Japanese pilots at the rear of their formation fired bursts of gun fire, including tracers, over the forward planes of the formation. Immediately, the Japs split up into several loose two plane sections, or individual one plane units.”

“We initiated a high side pass with all eight planes,” recalled Outlaw. The VF 32 planes began their attack from the Zekes’ starboard beam at a distance of 2,000 yards with an altitude advantage of 2,000 feet. “On the first pass, we flamed eight Zeros.”

Outlaw and Reeves tore into the Japanese fighters. They got behind a two-plane enemy section flying 100 feet apart. Outlaw fired his first volley into one of the planes, striking it along “the fuselage and wing roots. It burst into flames and dived downward.” Not to be outdone, Reeves fired into the second plane. “It immediately smoked, flamed, and exploded.”

A second two-plane section was soon encountered and “approached from the stern.” Outlaw’s “…long burst into the fuselage resulted in the Zeke exploding. It was necessary to fly through the debris and flames.” Reeves launched his attack on the second plane from “…its starboard quarter. The bursts of fire hit along the starboard wing roots causing smoke, then fire, and in a brief time the plane exploded.”

“In accordance with squadron doctrine,” Outlaw related, “Hills took his division up to about 12,000 feet to provide high cover for my division as we continued to attack the enemy pilots. We continued to bore in on them two planes at a time while maintaining our division integrity and particularly maintaining our section integrity. Dagwood flew so close to me that I never lost sight of him out of the corner of my eye.”

Richard May spotted an enemy plane “swinging in on the skipper’s tail.” He “went full deflection” and unleashed “four streams of tracers” on the Japanese pilot, hitting him on the left wing and gas tank. The plane “exploded in my face. Damn! I hated to fly through debris, which could disable my prop or control surfaces.”

“For a short time after the attack started,” read the VF 32 action report, “it appeared part of the enemy planes were going to form into some tactical formation. However, this impression was soon dispelled as the enemy did not seem inclined to attempt any organized tactical support of one another. After the VF 32 pilots made their first few runs, the enemy pilots displayed no air discipline or planned strategy, performing as a poorly or incompetently trained group without apparent leadership.”

Outlaw’s third victory required “a slight deflection shot. Flames were coming from the starboard wing root. The plane did not explode, but was seen burning all the way down” to the sea. Reeves’s third kill was “first sighted at some distance and the attack was speedily pressed. It was necessary to use a full deflection shot with about a two second burst. The shots hit the engine area and cockpit. The plane burst into flames and dived downward.”

May and Pond came upon a pair of Zekes. May bore down on the Japanese pilot “executing a Split S. A burst of fire caught the enemy plane in the starboard side of the engine and forward part of the fuselage causing it to burst into a mass of flames.” Pond engaged the other Zeke, which had initiated a “climbing right turn. The attack was pressed from a short distance off the enemy’s starboard quarter. A long burst into the cockpit and starboard wing area resulted in an explosion and disintegration of the Zeke.”

May’s next victim saw him coming and “immediately went into a fairly steep dive. The VF plane pushed over and soon closed the distance. The attack was made from nearly dead astern of the enemy plane. A long burst into the fuselage caused the Zeke to flame and go on down in a steep dive. It was noted that many plane parts were flying off.”

Pond’s second kill “made about a half roll, then straightened out again. It then made a sharp turn to the left enabling the VF 32 plane to attack from the enemy’s port quarter. A good burst into the engine and forward fuselage area started the Zeke smoking and flames emitting from the bottom of the fuselage. The enemy then turned straight down and was last seen in a mass of flames and out of control.”

May felt he was “in the middle of a hailstorm. Our danger of collision was almost as critical as being shot out of the sky. I lost track of time. Sweat was running into my eyes … my flight suit was soaked through … my neck ached from the constant twisting of my head to see all of the areas around us. My right arm ached from the hard effort of constantly manhandling the Hellcat in high-G turns.”

From his position flying ‘high cover,’ Hollis Hills noticed “two Zekes making ready to press an attack on Lieutenant Commander Outlaw’s plane from his stern. Rather than pursuing other enemy planes near [his] division at about the same altitude, Lieutenant Hills led his division in an attack on the two Zekes, which were ready to open fire on Lieutenant Commander Outlaw’s plane. A long burst was fired at the one nearest the friendly plane, striking it in the engine and wing roots. This Zeke was last seen diving in a mass of flames.” Hills struck the second Japanese plane with “two long bursts of fire. This plane stopped maneuvering and commenced to smoke from the section around the engine. Lieutenant (jg) McEachern then fired a burst into the Zeke and observed that it was descending in a mass of flames.”

McEachern next saw a “…Zeke coming up from below. This VF 32 pilot turned the nose of his plane down enough to bring the enemy into his sights and fired a long burst into the engine and wing area. This Zeke was seen by others in the flight to be going down engulfed in smoke, out of control, and diving straight for the water at a low altitude. The gun camera film showed that this Zeke was struck heavy in the vital area around the engine and the cockpit.”

The section of McClaugherty and Schulze joined the fray. After Hills and McEachern fired short bursts into a Zeke, the plane dropped down in front of Bear. His “attack was then made from about 15 degrees off the stern with a three second burst of fire. The Jap plane exploded and disintegrated.” Schulze was making a climbing right turn when he spied a Zeke “making a climbing left turn and heading direct for [his] VF 32 plane. The attack against this enemy plane was started as a head on run.” When Schulze started firing “the Zeke turned more so that the final burst was fired at an angle of about 30 degrees from the Zeke’s bow.” McClaugherty saw the plane “going straight down to the water, leaving a great stream of smoke, with flames.”

Outlaw’s fourth Zeke was lashed with a “good burst” from 200 feet and “went down in a good mass of flames.” His wingman’s fourth victim “was flying at an altitude of about 500 feet. The approach was made from dead astern. After a burst of fire flames were seen coming from the area of the cockpit. The enemy plane immediately made a steep bank and dived into the water.” Outlaw’s fifth kill “was sighted flying at a height of about twenty feet above the water and jinking. Fire was opened at long range. The port wing dropped into the water and the plane sank immediately.”

Decades later Outlaw made an addition to the story of his last victory that, for some reason, never made it into the action report: “At a fairly low altitude of 1,000 feet over the middle of Truk Lagoon, I ran out of gas in my belly tank. My heart came up into my throat, and I was scared to death that my engine might not catch again. However, with the rapid application of the fuel pump and shifting tanks, I was able to start the engine and pull out at an altitude of about 500 feet, Dagwood still being on my wing.”

Then the retired rear admiral made a further admission. “In the excitement of battle I made a serious error, in that our doctrine called for me to drop my auxiliary gas tank, which was a signal for each pilot to drop his, prior to entering a dogfight. In the excitement I forgot to do this. Consequently, we fought the entire thing with all of our belly tanks still attached to our planes, and we returned home that way, without ever receiving a single bullet hole in one of our aircraft.” Actually, Richard May sustained a seven-inch hole in his port wing. That was it.

Outlaw, Reeves, May, and Hills accounted for 15 of the 21 Japanese pilots who lost their lives against VF 32 that morning. All eight of the Hellcats returned to the carrier. As close as anyone could remember the fight lasted less than 10 minutes.

“When Outlaw landed back on Langley he held up five fingers,” a news article stated a few weeks later. “The carrier’s skipper, standing on the bridge, nodded with pleasure, thinking the eight planes had shot down a total of five Japs. Then, as the other planes landed and held up four, three, two and one fingers, he got so excited he couldn’t talk for a few minutes. The pilots claim he did a jig on the bridge, but the skipper insists he maintained his dignity.”

“This successful operation,” Outlaw wrote in his after-action report, “can be attributed largely to the fact that the VF 32 planes at all times maintained a close and proper tactical organization. The divisions and various sections worked in complete harmony. It is felt that the results of these eight planes, in their encounter with the enemy who had a great numerical superiority, merits distinction.” Seventy-six years later, that distinction is well worth remembering.

Eddie Outlaw became an “ace in a day” over Truk and served as Captain of the aircraft carrier USS Intrepid in 1959. He retired in 1969, and today his grandson bears his name.

Commander Richard H. May ended the war with seven kills and wrote an account of his service titled Hell Above. Commander Hollis Hills died in 2009 at the age of 94. The last of his several wives said he loved women, smooth scotch, and fast cars.

Dagwood Reeves started a strafing run next to Eddie Outlaw over Saipan’s Tanapag Harbor on June 11, 1944. He was never seen again.

Contributor Chris Marks writes from his home in Amana, Iowa.