By Christopher Miskimon

As the winter of 1944-1945 slowly gave way to spring, the combined Allied armies ground their way into Germany. Years of fighting in Europe, North Africa, Eastern Europe, and the Mediterranean had culminated in these final months of bitter loss, surrender, and annihilation for the Nazi Reich.

In the East, Soviet armies approached Berlin itself while Hitler stood over a map in his bunker, issuing orders to armies that no longer existed. In the West, the Allies had crossed the Rhine and were moving into the German heartland. Large numbers of German troops, once the masters of Europe, now bowed to the inevitable and surrendered en masse, while many civilians adorned their towns with white flags, bedsheets, tablecloths, anything that would spare their towns the destruction the advancing Allied troops could mete out. The pace of this advance was often so fast that reconnaissance units and advance forces captured entire towns and villages with hardly a shot fired. At times it resembled the lightning movement across France in the days after the breakout from Normandy.

This was not always the case, however. The Nazis could still put up a spirited, dogged, and determined resistance, making Allied troops pay for every foot of the Fatherland they seized. One such place was Aschaffenburg, a city of about 38,000 nestled on the east bank of a large bend in the Main River some 40 miles from Frankfurt. Here, a German major named Lamberth, using a motley collection of SS troops, replacements, convalescing wounded, officer candidates, and civilians, would turn the city into a fortress of resistance. Unexpectedly, for over a week, they held off American efforts to take it. In the end the city would be all but destroyed, with thousands of dead and wounded, pounded by the combined arms of the U.S. 45th Infantry Division.

The history of Aschaffenburg dates to Roman times. By the time of the Third Reich, it was a major hub for water and rail transport, and the city also boasted extensive industry. In addition, there was a substantial military presence, as Aschaffenburg was home to the 106th Infantry Regiment. Engineer and artillery units were also stationed there, along with a reserve officer’s training school. Finally, a large number of wounded soldiers were recovering in local hospitals from either battle wounds or illnesses, awaiting return to their units.

The terrain in and around the town favored the defender. To the north, south, and east are the wooded foothills of the Spessart Mountains, dotted with smaller towns and villages. The Main River, while not particularly large, would be a fearsome obstacle to cross if the attackers were under fire. The city itself had rail lines and two roads converging into it.

Two large buildings dominated the city, the Stiftskirche, a 10th-century church that sat on the city’s highest point, and the Schloss Johannesburg, a stout 17th-century palace that sat nearly in the city center close to the riverfront. The military barracks were clustered mostly in the southeast portion of Aschaffenburg, with training areas farther south. These barracks, along with a military warehouse nearby, were stoutly constructed, and several would become strongpoints during the fight. With the river to one side and mostly high ground surrounding it, Aschaffenburg sat in a depression with a number of small towns and villages in the immediate vicinity.

The German forces available for the defense were a disparate collection representing the qualitative mix of troops available to the Third Reich this late in the war. Since Aschaffenburg was home to the 106th Infantry Regiment, its small replacement and training unit was in the city. Added to this was a group of officer candidates undergoing training in the area. Unlike the U.S. system wherein men with a certain educational level were admitted to officer training regardless of experience, many of the German candidates were men with up to three years of military experience.

The soldiers in the convalescent hospitals, while perhaps not up to full fighting condition, were also combat experienced. The 9th Engineer Battalion and 15th Artillery Regiment with a few guns were present to support the defenders. These, along with a small SS contingent, represented the better troops available. There were no tanks, and only a handful of artillery, mortars, and Nebelwerfer rocket launchers were on hand.

Reinforcing these men were seven companies of Volkssturm, essentially militia troops with limited training and equipment. Nevertheless they would fight. Last, the civilian populace played its part in the battle as well. Shortly after contact with the advancing Americans, the city leadership ordered the elderly, women, and children out of the city, stating that anyone who remained would be expected to take up arms or assist in the fight. Those who stayed had no choice but to participate to some degree. While very few actually fought, many more tended casualties, carried supplies, and worked as runners during the coming fight. The Americans would later report fighting with numbers of civilians.

About 5,000 men formed KampfKommando Aschaffenburg, a battle group designation pulling all the city’s units under one command. This label came directly from Hitler, establishing the city as a fortress requiring a supreme effort in its defense. Reinforcements received during the fighting would bring the total strength of the garrison to some 8,500.

The man selected to lead this battle group was Major Emil Lamberth, a World War I veteran. He had arrived in the city to take over the 9th Engineers in June 1944. On January 30, 1945, he was appointed senior garrison commander. He had assisted in planning the defenses of the city, tying them in with the larger defense line along the Main River. On March 5, he was appointed combat group commander and swore an oath to defend the city, placing himself under Hitler’s direct command. A small SS delegation came to Aschaffenburg to oversee the diligence of the battle group’s effort. Despite Nazi Party interference, Lamberth was able to pass muster with his defensive scheme.

The overall plan was designed to be a link in the chain of defenses along the Main. A number of positions were created along the river’s east bank, using the Main itself as a natural obstacle. A line of bunkers had been created for this defensive belt, and the Aschaffenburg garrison would make use of some of them. Additional strongpoints were set up both to establish a perimeter around the city and to create a defense in depth.

Several of the outlying towns, such as Schweinheim and Mainaschaff, would be heavily defended. In Aschaffenburg itself, the waterfront and the central section around the Schloss Johannesburg were fortified. In truth, most of the town was composed of stone or masonry buildings packed closely together with the relatively narrow streets common to older European cities. On their own these buildings provided good cover that was resistant to small arms and, to a limited extent, tank and artillery fire. The bridges on the Main would naturally be blown.

The main German unit outside the city was the 36th Volksgrenadier Division, with a strength of perhaps 6,500, only a third of them trained. It had three half-strength battalions of artillery and two assault guns.

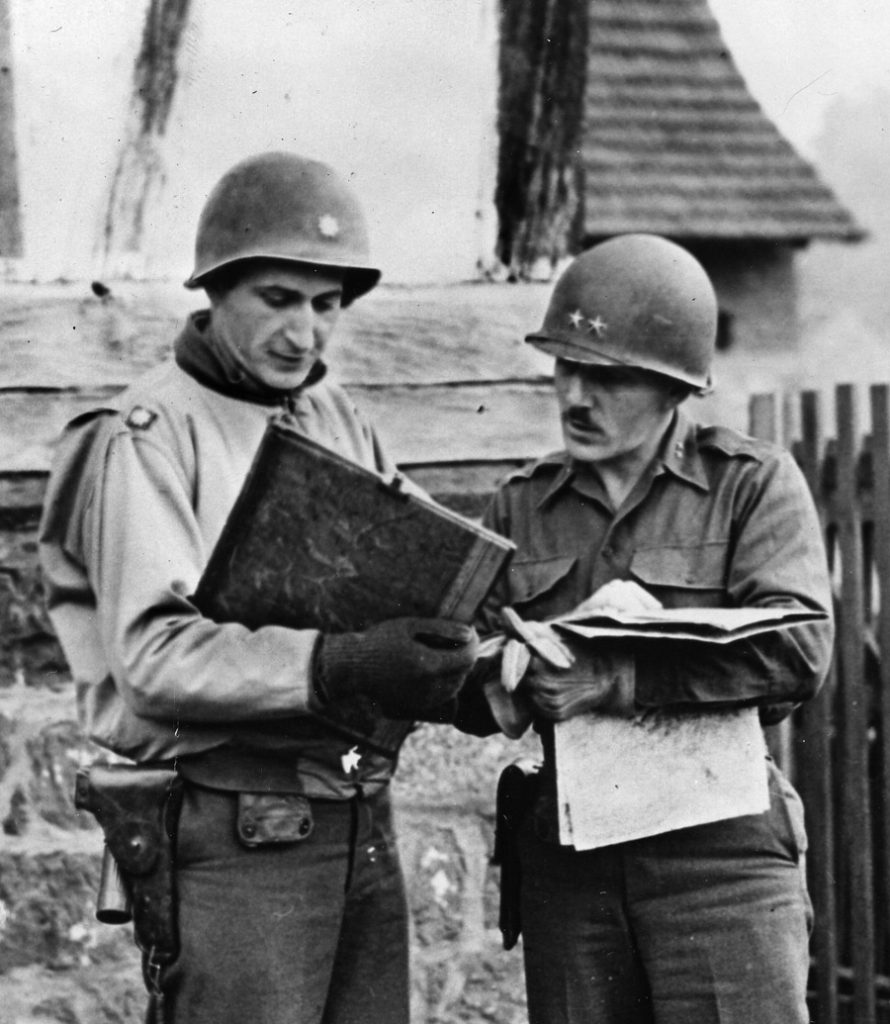

The Aschaffenburg command would have been tied more firmly into the overall defense of the region, but time ran out when the Americans arrived. On Palm Sunday, March 25, at 9 am, Lamberth received word that the Americans were only nine miles west of the city at Babenhausen. By noon sentries on duty in the towers of the Schloss Johannesburg sighted the lead U.S. elements. Combat Command B (CCB) of the 4th Armored Division was leading the way for General George S. Patton’s Third Army to cross the Main River while the bridges still stood.

Commanded by the now-famous Colonel Creighton Abrams, CCB plunged straight down the road from Babenhausen to Aschaffenburg toward the primary road bridge over the river. This bridge crossed the Main directly into the city from an area on the west bank known as the Nilkheim salient, which was named for the town at its southern end.

CCB reached the bridge and immediately tried to cross. Intense German small-arms fire poured into the Americans, but they pressed on. The lead U.S. tank nosed onto the span and started across. Instantly it took numerous hits; antitank rounds, hand-held panzerfausts, and mortar fire all pummeled the hapless Sherman, and it exploded. Seconds later, the Germans demolished the bridge, sending the span and the Sherman into the river below.

CCB pulled back from the bridge toward Nilkheim. As this was happening, the commander of the 10th Armored Infantry Battalion, Lt. Col. Harold Cohen, received word from his reconnaissance platoon that a railroad bridge south of Nilkheim was still standing as well. Though prepared for demolition, the Germans had failed to defend it as heavily as the road bridge. Cohen ordered his scouts to seize the bridge, grabbing any armored vehicles nearby for fire support.

Despite taking heavy fire, the scouts rushed across and quickly started disabling the aerial bombs mounted on the bridge, pushing them into the river and cutting any wires they found. Cohen then sent three of his infantry companies across to form a bridgehead. The infantry’s half-tracks and a few tanks from Abrams’s 37th Tank Battalion quickly followed. Within a mere half hour of the German sentries spotting them, CCB had crossed the river and was fighting its way up two hills known as the Erbig and the Bischberg south of Schweinheim. It had all happened so fast that the Germans had not had time to destroy the bridge as planned. The German officer in charge of the bridge later claimed there were no detonators for the explosives on the span.

Trying to keep its momentum going, CCB tried to push into Schweinheim in mid-afternoon. Defending it were several units composed of replacement troops and officer candidates, well dug-in and with an engineer platoon attached. American tanks and infantry moved across open fields toward the town and stiff resistance. In places the combat became hand to hand. Several tanks were lost before the Americans pulled back to the hills. Some U.S. troops had moved north along the river to the outskirts of Aschaffenburg, while others mopped up isolated German pockets in the area.

As the first day of the battle ended, the Americans had seized a valuable bridgehead but had failed to get enough forces across to exploit it before the Germans began reinforcing. At midnight a boundary change was to take place with the lines delineating the responsibility of the local American units changing. That boundary line shifted north, and Aschaffenburg would then be in the zone of the 45th Infantry Division, a unit of the XV Corps of the U.S. Seventh Army. Lacking sufficient infantry for an urban operation, 4th Armored prepared to hand over the battle. German reinforcements continued to arrive, and Lamberth strengthened the defenses in Schweinheim and to the east of the American bridgehead.

Then began a strange episode, known generally as the Hammelburg Raid. Although it was separate from the battle of Aschaffenburg, it certainly influenced it. General Patton dispatched a task force of tanks, armored infantry, and artillery past Aschaffenburg toward the town of Hammelburg, the location of a prison camp holding Allied officers, including Patton’s son-in-law, Lt. Col. John Waters, who had been captured in Tunisia some two years earlier.

Much of March 26 was spent preparing a force of 294 men, commanded by Captain Abraham Baum, to break through enemy lines, advance to Hammelburg, liberate the camp, and bring back the POWs. A 30-minute artillery barrage preceded the attack, which had to move through the southern end of heavily defended Schweinheim to reach the road to Hammelburg. Baum and his men did not get through the town until midnight, but they pushed on. Once through the main defensive line, they advanced rapidly toward the POW camp, shooting up several trains carrying reinforcements and supplies along the way. Baum’s force reached the camp, where there were far too many POWs to evacuate, tried to fight its way back with a portion of them, and was essentially hunted down and all its men killed or captured.

The initial reports of an American column penetrating so deeply caused confusion among German commanders, who feared a U.S. breakthrough. Additional reinforcements were sent to the area. Much effort was spent over the next several days containing and capturing Baum’s force, diverting some attention away from Aschaffenburg itself. Still, several company- and battalion-sized training units began to arrive around Aschaffenburg to reinforce the defenders.

With a portion of its strength now detached for the raid, CCB withdrew to the high ground south of the city. Even the hard-won foothold in Schweinheim was abandoned. Early the next morning, March 27, CCB started withdrawing across the Main, being replaced in the bridgehead by the 1st Battalion, 104th Infantry Regiment of the 26th Division, which had been attached to the 4th Armored.

With the area now in the zone of the XV Corps, the 45th Infantry Division was ordered to Aschaffenburg. The 45th, commanded by the former head of the First Special Service Force, Maj. Gen. Robert Frederick, was a veteran force that had been in combat since the invasion of Sicily in 1943.

Frederick ordered the 157th Regiment, commanded by Colonel Walter P. O’Brien, to take the city. The regiment’s third battalion, commanded by Lt. Col. Felix Sparks, was ordered to lead the way and occupy the hills in the bridgehead. The men of the third battalion, indeed the entire regiment, were told the town had been cleared by the Third Army, which of course it had not. Sparks received a cryptic warning about not firing on any American tanks he saw to his front but otherwise was not informed about Captain Baum’s task force or its mission. Sparks would not even know of the raid until years later.

The battalion reached the railroad bridge by 2 pm on March 27 and began to cross. Mortar and rifle fire immediately began to fall upon them. Sparks found a company of reconnaissance troops equipped with jeeps and armored cars guarding the bridge. The lieutenant commanding the recon troops told Sparks that his orders had been to hold the bridge until relieved. Sparks relieved him and sent his battalion across the river into defensive positions.

Two attacks from Schweinheim were beaten back. From the high ground, Sparks looked through his binoculars at Schweinheim and Aschaffenburg; the streets were devoid of movement, and no white flags or bedsheets hung from the windows.

Lieutenant Colonel Sparks recalled, “I got information from a civilian that there were several thousand Germans in the town. I radioed that information back to the division, and I don’t think anybody believed me.” The area was not secured, and the 157th would have to fight for it.

Two rifle companies supported by an attached tank destroyer platoon and an artillery battery from the 158th Field Artillery Battalion were sent into Schweinheim. This attack succeeded in taking a few prisoners and regaining the lost foothold vacated by CCB of the 4th Armored. On the German side, efforts continued at organizing an assortment of units into a cohesive force. The commander of the German 36th Volksgrenadier Division began planning a counterattack to throw the Americans back across the Main using what infantry and artillery were available.

On the morning of the fourth day of the battle, the rest of the 157th Regiment arrived and began crossing the river. The only enemy activity was a series of Me-109 sorties against the bridge area. A plan was devised to take Aschaffenburg using the three battalions of the regiment with its attached supporting units: the 158th Field Artillery Battalion equipped with 105mm howitzers, Company A of the 191st Tank Battalion, Company B of the 645th Tank Destroyer Battalion, and Company C of the 2nd Chemical Mortar Battalion.

Sparks’s 3/157th began assembling east of Erbig Hill, preparing for an attack on Schweinheim. The 2/157th, under Major Gus Heilman, would attack to the north along the river into Aschaffenburg itself. Company F would move north along the riverbank with its right flank protected by Company E, while the battalion’s Company G trailed in reserve. This unit would receive some additional support from Company D of the 191st Tank Battalion equipped with the M-5 Stuart light tank. Lt. Col. Ralph Krieger’s 1/157th would take up position between the two other battalions; it was to essentially sit in reserve until Schweinheim was secure and then take the ground northwest of it.

The attack began with an artillery preparation. Sparks’s troops attacked into the eastern end of Schweinheim, I Company on the left, K Company on the right, L Company in reserve. German resistance was immediate and fierce. Despite the heavy artillery fire and air support the Americans threw at the town, only the outskirts of Schweinheim were in U.S. hands when the attack was halted at nightfall.

The 2/157th started north toward Aschaffenburg and likewise met heavy German resistance from the outset. Despite punishing machine-gun and panzerfaust fire, Company F pushed forward some two kilometers before it too stopped for the night. Company C of the 1/157th moved into the gap between the 2nd and 3rd Battalions to fill the vulnerable separation between them. The day’s advance had been bitterly contested by the German defenders, and overall there had been minimal progress. German mortar fire fell on the Americans, prompting them to reply with counterbattery fire throughout the night of March 28.

During the day, soldiers of the 1/157th found a warehouse full of liquor. Apparently vintages confiscated from all over Europe had been brought to Aschaffenburg for storage. This bounty was quickly distributed around the regiment, and the unit’s unofficial history includes a recipe for a drink the troops concocted using their spoils of war. Called the “157th Zombie,” it consisted of “¼ Cognac, ¼ Benedictine, ¼ Contreau and ¼ of any other bottle handy, followed by a champagne chaser.” The history went on to note, “… many days passed before some canteens carried anything so tasteless as water.”

After combat engineers laid planking to improve the railroad bridge, the other regiments of the 45th, the 179th and 180th, crossed the Main and headed south to link up with the 3rd Infantry Division. The 179th tied in with the 157th’s flank, while the 180th continued southward to make contact with the 3rd Division.

As the battle entered its fifth day, the struggle for Aschaffenburg focused around the southern end of the city, including Schweinheim. The fight centered on the advance of the 157th Regiment. The high ground between Schweinheim and Aschaffenburg had to be kept out of American hands as long as possible. The airstrikes and artillery bombardment had already reduced portions of both areas to rubble.

The German officer candidates positioned themselves in various strongpoints throughout Schweinheim. Many of these fortified houses had been connected by a series of underground tunnels through which the Germans would reoccupy positions already cleared by the Americans. This would come as a nasty surprise to GIs trying to clear the next house, only to be fired on from the last one taken. Snipers used their knowledge of the town to constantly infiltrate into the American rear areas.

While these clever tactics did greatly hamper the U.S. advance, they also contributed to the massive destruction Aschaffenburg eventually suffered. The veteran troops of the U.S. 45th Division, not having expected to fight here in the first place and fully aware of the risks of urban combat, did not hesitate to use every bit of firepower at their disposal to blast the Germans out of their positions. The infantrymen of the 157th knew how to coordinate with tanks, artillery, and air support after almost two years of fighting; now every bit of that knowledge would come into play at Aschaffenburg.

At 7:30 am on March 29, both attacking American battalions resumed their assaults. The 2/157th once again ran into immediate and heavy resistance and had to call up Sherman tanks to pour direct fire into the fortified houses. In Schweinheim, Sparks attacked with two companies advancing side by side, the third in reserve. Company C, on the left flank, took an hour to reach the first street of the town as bitter house-to-house fighting slowed the advance to a crawl.

Determined resistance caused the Americans to pull back and dig in while artillery and mortar fire softened the German positions. To try and break the enemy line, O’Brien sent his reserve battalion against the center of the German line. The resistance there proved just as stiff as the rest of the line, and the attack gained little.

In Schweinheim, Sparks’s battalion continued to push forward block by block. To assist this effort, all available artillery was concentrated on the town. Tanks and tank destroyers fired directly into enemy strongpoints. Buildings had to be cleared one at a time. The tanks and tank destroyers directed their fire on a targeted building, giving the infantry a chance to storm it while the Germans inside were pinned. In the confines of the German town, vicious combat was the rule. At short range, two Shermans of Company A, 191st Tank Battalion were lost to antitank fire.

Approximately 3,000 civilians were still in the town, many of them casualties whom the German medical staff was hard-pressed to care for. Major Lamberth ordered an officer from among the convalescent soldiers to be hanged when he was accused of desertion. The officer, a Leutnant Heymann, had been told on March 26 to register with the local command so he could be assigned to the defense. Later that day he was arrested for not having registered and for allegedly making an English sign found hidden in a basement. He was court-martialed, convicted, and on the 29th, taken into the street in front of a café, and hanged from a lamppost. A sign calling him a coward was placed on the body, and the corpse was left hanging.

Just after midnight on March 29, the counterattack by the 36th Volksgrenadier was set in motion. Aimed at the high ground around Erbig Hill, the 165th Grenadier Regiment broke through the American perimeter on the south and east sides of the bridgehead. Four hours later they had reached the area between the Erbig and Bischberg Hills while the 87th Grenadier Regiment had penetrated on the southern end of the perimeter. Along with a battalion of the 179th Regiment, heavy counterattacks by the 157th, again using coordinated tank and artillery support, drove back the Germans to their starting points by noon.

The German position was becoming untenable as the divisions around Aschaffenburg were steadily pushed back, leaving the city further isolated. By the afternoon, the German LXXXII Corps conceded and issued orders for its units to withdraw, leaving Aschaffenburg cut off.

To complete this isolation, General Frederick ordered his 179th and 180th Regiments to push to the east and position themselves to flank Aschaffenburg. While they did so, the 157th continued to slowly gain ground into Schweinheim and the southern outskirts of the city. The defenders launched a series of five counterattacks, each company sized. Although the Americans took some casualties, they repulsed each of them while inflicting serious and unrecoverable losses on the enemy.

In Schweinheim, 3/157th was able to cut the town in two, with small pockets of defenders remaining in the northeast and northwest corners. In an attempt to flank the German line, two companies (A and B) went around Schweinheim to attack the high ground to the southeast. Though under fire, they were able to advance 1,000 yards. The American commanders were now seeing that a direct assault would not work and that enveloping their enemy was the better option. All the German counterattacks had failed, and now they could do little but grimly hold on and inflict the maximum possible loss on the attackers.

Again the 45th Division maximized the firepower of its support assets. More armor from the 191st Tank Battalion was brought into play. The Americans also brought in additional artillery. The four artillery battalions of the neighboring 44th Division were attached to the 45th. Five corps-level battalions, some with massive 8-inch howitzers, were likewise given to the 45th. So much artillery now pounded the city that some Germans likened it to machine-gun fire. Overhead, P-47 Thunderbolts of the 64th Fighter Wing began pelting Aschaffenburg with napalm, rockets, and .50-caliber bullets.

The defenders, now on their own, lacked the troops or artillery to either retake or destroy the bridge, and a sortie by a pair of Messerschmitt Me-262 jets failed to down it. After dark on March 30, four German Navy frogmen tried to place an explosive charge on the bridge by floating down the Main from Aschaffenburg. Mortar fire was called down upon them, killing all four frogmen.

On the last day of March, the envelopment of the city continued. While 2/157th continued to press into the southern end of Aschaffenburg and 3/157th mopped up in Schweinheim, 1/157th struck north along the city’s eastern side. The 179th Regiment, to the right flank of the 157th, pressed north as well to help complete the envelopment. In the air the P-47s reappeared and continued to rain destruction on the garrison. If the planes were not overhead, massed artillery, often firing time-on-target missions, pounded the remaining buildings into rubble. The enemy headquarters in the Schloss Johannesburg was hit repeatedly. White phosphorous rounds from the 4.2-inch mortars started fires here and there, while self-propelled guns were brought up to support the GIs directly.

The Germans responded with intense mortar fire—one barrage dropped 200 rounds in 15 minutes—and continued sniping and infiltrating back into lost ground. Near Schweinheim, two tanks—one identified as a German Mark VI Tiger and the other a captured Sherman hastily painted with German crosses and the word beutepanzer (captured tank)—fired on the Americans, halting their advance. An M36 tank destroyer of the 645th destroyed the Sherman with its 90mm gun. The body of a German crewman hung out of one of the hull hatches, burned and blackened. The Mark VI was quickly destroyed as well.

At noon the 157th’s adjutant, Captain Anse Speairs, flew over Schloss Johannesburg and dropped a message. This ultimatum demanded the garrison’s surrender, guaranteed observance of the Geneva Conventions, and threatened to level the town if the Germans continued the fight. The note ended ominously, “The fate of Aschaffenburg is in your hands.” Additional surrender flyers were dropped around the city.

In the afternoon American attention focused on the barracks just north of Schweinheim. By nightfall Company K of 3/157th had won a small foothold in the Artillerie Kaserne nearest Schweinheim, but otherwise let fire support begin the process of wearing down the entrenched enemy.

Easter Sunday, April 1, 1945, was not a day of peace in Aschaffenburg. The 1/157th and 3/179th continued their envelopment by seizing the surrounding towns of Gailbach, Halbach, Goldbach, and Hoesbach. The first two towns fell quickly; the last two held out until the next afternoon. This move completed the encirclement.

To exploit this flank, the barracks area had to be taken. Sparks’s Company K, 3/157th attacked again at 1 pm following six hours of artillery preparation. Small-arms fire from some 100 convalescents drove the attack back. Now tanks moved up and fired white phosphorous shells into the enemy positions. The GIs stormed the building and took it in hard room-to-room combat. The next enemy position, the Bois-Brule Kaserne across the street, was taken the same way. Within four hours both were in American hands. The fighting was so intense that every defender of the second building was wounded.

The last barracks to be taken was the Pionier Kaserne, northwest of the previous two and much larger. This mission fell to the 2/157th, which planned ahead and took note of the fight for the previous two strongpoints. Besides the usual artillery barrage, two M12 self-propelled 155mm howitzers were brought up to a hill overlooking the target. They fired more than 100 rounds directly into the Kaserne while the American troops struggled to take it. By day’s end, half of it had fallen.

The incessant pounding of the artillery, air support, mortars, and armor were now taking their toll on the Germans. While many of their positions were so well fortified that they were relatively safe from the physical effects of the fire, it was now affecting them mentally, depriving them of rest and making movement of supplies hazardous.

The last full day of fighting came on April 2. Resistance continued, but it was no longer organized. The 157th’s sister regiments finished seizing the surrounding towns and established additional roadblocks. After mopping-up operations, 1/157th moved north and linked up with the 324th Infantry Regiment of the 44th Division, which had moved into position north of Aschaffenburg. Late in the morning most of the German defenders of the Pionier Kaserne pulled out, leaving only a few strongpoints that fell by mid-afternoon.

As night fell, 2/157th had fought its way into the city’s heart while 3/157th broke into the eastern suburbs, occupying a wooded park that extended into Aschaffenburg’s center. The artillery and air strikes continued as more and more Germans surrendered. Over 1,100 were captured on April 2. The remaining defenders clustered around the Schloss.

Fortunately, Major Lamberth had decided to end what was now a hopeless battle. At 7 am he sent a Volkssturm officer with a captured American to seek terms. Colonel O’Brien refused to negotiate and demanded Lamberth surrender by 8 am or the fighting would continue.

On the American side, unaware of the possible surrender, GIs readied artillery, tanks, and planes. O’Brien sent two German-speaking lieutenants with the surrender party to make the message clear. Lamberth agreed to capitulate but would not personally surrender to an inferior-ranking officer. Lt. Col. Sparks was the nearest ranking officer, so O’Brien sent him to the Schloss.

As Sparks recalled, “So I got word and I was a few blocks away. So I drove up there in my jeep and got out, went up to the building, and told this major, ‘I’m a Colonel and now I want you to surrender.’ So this major gave an order, and all of his officers came out of the building single file. They took off their pistol belts and dropped them at my feet. I knew there were still some strongpoints the Germans had left, so I told the major that he had to tell them to give up too. He said, ‘all right.’ So I put him in a jeep with me and we drove around and he pointed out where the strongpoints were and I’d make him go up and yell to them in German to surrender. There were three or four of them [strongpoints]. And that was the end of Aschaffenburg.” Sparks recalled seeing the body of the German lieutenant still hanging from its lamppost. The surrender took place at 9 am. With the city declared cleared by 1 pm, the weary troops of the 157th Regiment moved to the towns of Goldbach and Hoesbach to reorganize.

The fate of Aschaffenburg was the destruction of 70 percent of the city, lost in a determined but wasted struggle. Of the 8,500 defenders, 1,600 were wounded or killed and 3,500 more became prisoners of war. The Americans suffered around 300 wounded and 20 killed. As the unofficial history of the 157th stated, “…the city itself now lay shattered as an example of the futility of resistance. It had been pounded to rubble, its occupants had been slaughtered, and those who survived were punch drunk from the day and night hammering by air, artillery and infantry.”