By Mark Carlson

Aboard each of the hundreds of Liberators and Flying Fortresses that daily left the soil of England bound for targets in Germany were ten young men.

Outwardly they were no different from any late-teen or early-twenties boy one would meet anywhere in America. Same faces, same names, same youthful vigor and sense of invincibility.

On their shoulders rested the hopes of a nation, a world at war.

Bombardiers and navigators; pilots and co-pilots; radio operators; flight engineers; and ball, waist, and tail gunners. Some were officers, most were sergeants. They came from factories and farms, small towns and big cities, but they each ended up in a narrow aluminum tube with four roaring engines, a dozen machine guns, and four tons of high explosives.

The Challenge

In early 1943, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill wrote a letter to Air Marshal Sir Charles Portal regarding his concerns about the U.S. Army Air Force’s ability to destroy Germany’s war industry: “The real question is not whether the American heavy bombers can penetrate into Germany by day without prohibitive losses, but how often they can do it and what weight of bombs they can discharge for the vast mass of ground personnel and materiel involved.”

In Churchill’s mind, the effectiveness of U.S. daylight bombing came down to this simple equation. At this point in the war, the RAF was already putting up as many as a thousand bombers over Germany, while the new Eighth Air Force Bomber Command was hard-pressed to put up as few as fifty.

For the Yanks, the time between August 1942 and April 1943 had a very steep learning curve. For one thing, pre-war bomber theorists were convinced that the heavy bomber, bristling with .50-caliber machine guns and flying nearly as fast as fighters, would need no escorts.

Furthermore, they never considered that bombers would have to fly as high as 30,000 feet in order to avoid German anti-aircraft fire. Therefore, the bombers were unpressurized, unarmored, and woefully under-armed in the brutally Darwinian world of modern aerial combat. The first bomber groups to mount raids over occupied France, Belgium, and the Low Countries made scarcely a dent in the Axis’s hold on the continent.

The Luftwaffe, already blooded by the Battle of Britain and the RAF’s night bombing raids, were initially cautious when they encountered the massive B-17 Flying Fortresses and B-24 Liberators in the summer and fall of 1942. But they soon learned that even with as many as a dozen light and heavy machine guns spurting from each plane, there was little to fear from the American bombers.

Soon, American bomber losses had become so significant that the entire concept of daylight precision bombing was under constant attack on both sides of the Atlantic. This was when Churchill stepped into the ring with his letter to Portal. But General Ira Eaker, head of Eighth Bomber Command, countered the PM’s concerns by stating that between the RAF and USAAF, Germany would be “bombed ‘round the clock.” This was just the kind of rhetoric Churchill loved, and he soon gave Eaker his cautious blessing.

During the first year of the air war over Europe, the USAAF bombers had not hit Germany with anything more than a few nuisance raids. The fighters and flak defenses over the occupied lands were relatively light compared to what awaited the Eighth and Fifteenth Air Forces bombers over the heart of the Third Reich.

“Your target for today, gentlemen…”

On dozens of dark airfields all over East Anglia on the southeast corner of England, neat rows of heavy bombers were being fueled and loaded with bombs and ammunition. A mission was set for that day. Overhead a solid cloud cover obscured the stars and moon. The air was drizzly and cold. But the meteorology wizards at “Pinetree” at Eighth Bomber Command HQ had predicted clear skies and fair conditions over the Channel and Germany.

The target, carefully selected from reconnaissance photos, intelligence analysis, and the current objectives of the high command, was already chosen. The bomb groups, wings, and divisions were alerted, and the mission operations order sent out by teletype.

Long before dawn lightened the cold sky, a lone man entered the Nissen huts where aircrews rested in uneasy slumber. Many were sleeping off the stress, fatigue, and leftover fear from the previous day’s mission. At 3 am, the CQ (Charge of Quarters) began waking up the crews. Holding a flashlight, he shook each man’s shoulder and made sure he was awake. There was the usual grumbling and swearing. But the groggy airmen began to stir, reaching for their cigarettes and clothes.

Radio operator Sergeant Don Hammond, who flew 28 missions with the infamous 100th Bomb Group, recalls “The Charge of Quarters came in and said ‘Hey, you’re flying. Briefing at 4 am, takeoff at 6:30.’”

At that moment, the bomber crews knew that they were facing another day of fighting for their lives in the air over enemy territory. The only question was, what target? A railroad yard, oil refinery, aircraft factory, or ball-bearing plant? Each one would be heavily defended by flak guns. And the moment they crossed the coast and headed over the continent, they would be set upon by hordes of Luftwaffe fighters. Just another day over the Third Reich.

Men pulled on long johns and flight suits. The veterans were used to the routine, making certain they carried nothing that would indicate their unit or any personal information, things that would be useful to the Germans. They wore dog tags and fleece-lined boots. A few put lucky charms into their pockets or bowed their heads in prayer.

Then, thinking about breakfast, they trudged out in the chilly darkness to walk to the mess hall. Some groups were lucky enough to have farmers nearby willing to sell produce to the Yanks. Hammond recalled, “We had fresh eggs, served to anyone who was flying.” But things weren’t the same all over.

Navigator Dick Tyhurst, a veteran of 35 missions with the 95th Bomb Group said, “At Horham we always had powdered eggs, toast, and coffee. Each squadron had 120 guys. Three squadrons, that’s 360 hungry men. No way are you going to have fresh eggs.”

The airmen then made their way over to the main Nissen hut for the mission briefing, conducted by the group commander and intelligence officer. Behind them was a large curtain covering a map of Europe.

“We went to the main hall with all the crews,” continued Hammond. “Armed sentries stayed at the door so we couldn’t get out. I thought that was kind of funny.”

Pilot John Gibbons, who survived 49 missions with the 100th, related his memories of the briefings: “The group C.O. said, ‘Gentlemen, your target for today is …’, then he pulled the curtain. We saw the blood-red ribbons stretch all the way from our bases across the Channel to Holland or Belgium and right into Germany. Those ribbons went right over all these fighter bases. Everybody in the room would just groan and sigh or mutter ‘Oh, goddamn.’”

The group commander gave the details of the mission, the target, and the course they were to take. He listed what other groups, wings, and divisions were also on the mission, along with their places in the formation. Upon hearing that one or another group would be in the low slot in the low wing, more muttering was heard. “Poor bastard, better them than us.”

“Tail-end Charlie” often caught the brunt of German attacks, particularly the Luftwaffe’s head-on attacks that had become a standard tactic by the spring of 1943.

Colonel Archie J. Old, Jr., of the 96th Bomb Group often took the low slots in a formation. “The low plane of the low squadron of the low group, that was the hot spot, often called ‘Coffin Corner.’ If you wanted to see a lot of fighters, that was where you would see them.”

The next matter was fighter escort—what units would follow them across the Channel, who would escort them to the target—and what call signs and codes were to be used. The most important details were rendezvous times and recall codes.

The group intelligence officer then detailed what kind of fighter opposition they might encounter, and what flak was protecting the target. The briefing often ended with a pep talk about how important the target was, how it must be hit and totally destroyed, and that it was essential to the war effort.

“That sounded great,” said Stephen King, a pilot of the 379th Group. “But we had heard it so many times it hardly registered. Besides, some of those places, like Regensburg, Bremen, Schweinfurt, and Frankfort had been hit more than once, and we kept having to go back and do it again. And every time cost us a lot of planes and crews.”

Then everyone synchronized their watches. The pilots and gunners left, leaving only the navigators and bombardiers, who were given instructions about route and target information.

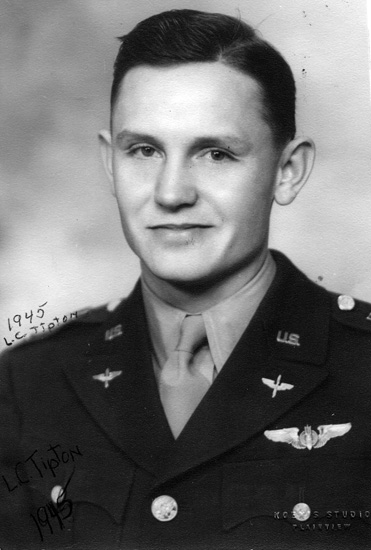

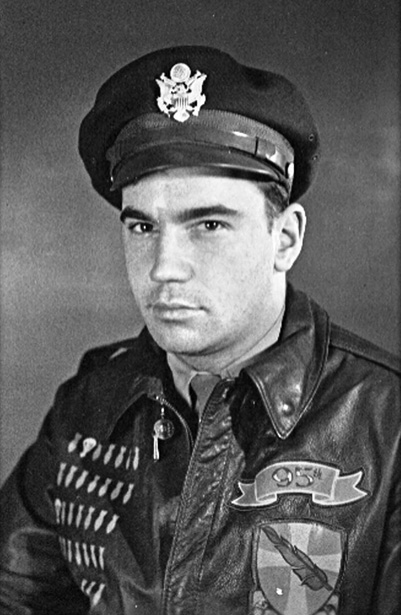

Lynn Tipton, a bombardier of the 493rd Bomb Group, said, “We were shown aerial photos and maps showing the bomb run and I.P., or Aiming Point. The group armorer said what bomb load we’d have.”

The radio operators were given the frequencies and codes and warned about radio silence.

“I got a sealed bag with my frequencies and information for the day,” remembered Hammond. “I had an escape kit with medical kit, fishhooks and line, some fake I.D. and maps. I had about $50 in gold to bribe civilians [in case I was shot down]. After briefing we drew our oxygen masks, electrically heated flight suit, Mae West, parachute, pistol, and flak vest.”

Sergeant Larry Goldstein, a radio operator in the 388th Bomb Group, had his first taste of combat in the dark days after the first Schweinfurt raid of August 1943: “We were rushed right into the 388th because of the heavy losses. Once we began missions, unless you were in the lead or deputy lead plane, the only thing we did was to listen for weather updates, fighter rendezvous information, or possible recall orders.”

Radio operators were also responsible for throwing out the aluminized Mylar strips known as “window” or “chaff” to confuse and overwhelm German radar.

The sky slowly turned from deep violet to dusty pink in the east as the crews stubbed out final cigarettes and drove out to the bombers waiting on the hardstands. By early 1944, most heavy bomb groups fielded 21 planes for a mission, with four in reserve for aborts; 210 young men walked up to their planes. Some planes bore rows of bomb symbols to denote the number of missions that the plane had flown. A few had swastikas for air-to-air kills. Many had patches covering flak and bullet holes.

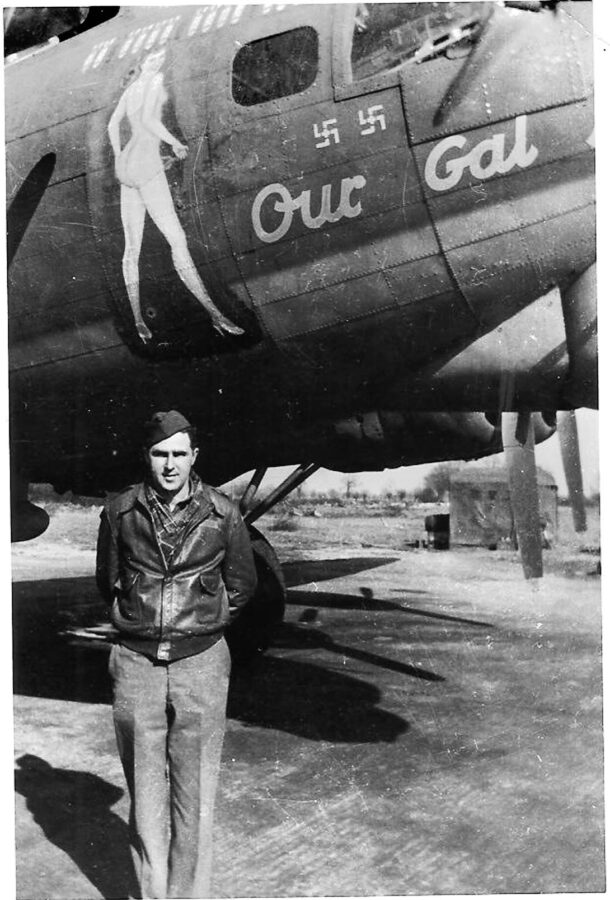

While Hollywood and popular culture supported the legend that every bomber had a nude girl painted on the nose, most nose art was whimsical, witty, or a double-entendre. Names like “Bad Check,” “Jersey Bounce,” “Witchcraft,” “Old Flak Sack,” “Worrywart,” “Nine Yanks and a Little Jerk,” and others predominated. But as the war dragged on and hundreds of bombers ended up as smoking wreckage on the ground, nose art became less common.

One pilot of the 96th Group, Ed Davidson, commented, “Each squadron was in its own line in the hardstands. We checked the bombs and fuel load and calculated the center of gravity.”

“Our ground-crew chief went over the damage and repairs from the previous mission with Lieutenant Stan Cebuhar and me,” said co-pilot Delton “Rip” Reopelle of the 379th.

Stanley Lawruk, a flight engineer with the 92nd said, “I walked with the ground-crew chief and inspected it to make sure everything was fine for flight.”

For a takeoff of 6:30 am hours, most crews were on board by 6:00. Every inch of the bombers’ aluminum skin was icy cold to the touch. The radio operator and gunners stepped through the aft door, while the officers and flight engineer went up into the small nose hatch. The interior smelled of metal, oil, fuel, and the faint tang of cordite. It was a sharp reminder that their plane had “seen the elephant”—a Civil War phrase meaning that one had been in combat—and would do so again today.

“I crawled into the tail and checked my ammunition,” Rich Tangradi, a 100th Group tail gunner, explained. “Two boxes, each with 600 rounds of one tracer, two armor piercing, and two incendiaries. I put the guns in their positions and lifted the receiver, put in the belt, then slammed it down and locked it. No one touched those guns but me.”

The other gunners prepared their positions and weapons, making certain that the ammunition feed lines were clear. They each had about 7,000 rounds, enough for about three minutes of sustained firing.

While the gunners were confident of their ability to fight off the Luftwaffe, flak was another matter. Flak caused more wounds than bullets and cannon shells. Although the small bits of shrapnel from bursting 88mm shells lost much of their velocity as they cut through the aluminum skin of the plane, they could still be deadly.

Early on, gunners sometimes hauled a scrap piece of protective steel onboard to stand or sit on, but this could affect a bomber’s critical center of gravity. The obvious answer was the flak vest and helmet, which arrived in the ETO (European Theater of Operations) by 1944. The helmet was based on the M1 infantry ballistic-steel helmet but had wide covers for earphones.

Materiel Command also devised a long vest with thin, overlapping plates of manganese steel sewn into the front and back that reduced flak wounds by almost 60 percent. But some men wanted more; a navigator with the 381st bomb Group persuaded an armorer to make a steel-lined jock strap to protect the “family jewels.”

Later, blankets lined with steel could be hung around crew positions without adding much weight.

The only thing left was the parachute, which crewmen kept nearby for quick retrieval.

The Sound of Freedom

About 10 minutes before takeoff, pilots switched on the energizers, starting up the electrical system. Bombardiers fitted their Norden bombsights and warmed up the motors and gyros. Once the doors and hatches were closed and latched, the crews called the pilot and checked in. Then they settled in for takeoff. The tail gunner and ball-turret gunner moved to the center of the fuselage until after takeoff.

At exactly 6:30 am, two yellow flares speared into the dawn sky over the control tower. No radio calls were made. All along the squadron lines, 84 huge radial engines roared into life, popping and banging as they warmed up. Gouts of blue flame spat from exhaust vents as the pilots adjusted throttles and mixture controls. The noise dominated the countryside as more groups started up at nearby airfields. Frightened birds took to the sky. Rudders, ailerons, and elevators moved, and flaps lowered. The bomb bay doors closed, hiding their deadly brood.

At 6:35 a yellow and a green flare were fired, and the planes moved out one by one onto the long airfield perimeter track to the end of the runway. At 7 am, when all was ready, two green flares arced into the sky.

The first plane, flown by the group leader, advanced its engines to full power, released its brakes, and moved down the runway. With four tons of bombs, 2,500 gallons of fuel, belts of ammo, and 10 crewmen, the bomber had to claw its way into the morning sky. Crashes were common, even expected, so fire and emergency crews were on alert during takeoff.

Flight Engineer Lawruk described a takeoff in the B-17: “The co-pilot released the brakes, and the pilot advanced the throttles. I stood between the two seats and called out the airspeed and kept an eye on the instruments. In the tail, the gunner would have been using an Aldis lamp to give the following plane a visual reference, especially in thick fog or low cloud.”

Co-pilot Ralph Golubock of the 44th Bomb Group recalled one takeoff during “Big Week,” the massive effort in late February 1944 to destroy the Reich’s aircraft and armaments industry. Leaving their field behind, Golubock’s heavily loaded B-24 had to make a long, grinding climb through heavy overcast. With visibility at zero, the pilots waited to break out into clear skies. “To our horror, we saw a huge flash of light in the sky. We all knew that two planes had collided and exploded. Just like that, 20 men had been killed.”

One by one the big planes lifted off. “Takeoff was done by section and squadron,” explained Ed Davidson. “We took off at 30-second intervals and climbed.”

Navigator Dick Tyhurst recalled, “We had three groups in the 13th Combat Wing: the 100th at Thorpe-Abbots, we were in the middle at Horham, and the 390th was at Framlingham to the southeast.”

Davidson said, “We used vertically-aimed radio beacons called ‘Bunchers.’ The airfields were roughly five miles apart. When we took off, we had to circle tightly over our beacon because five miles away were other groups within our combat wing. Sometimes we’d come up out of the clouds and five miles away we’d see another B-17 come out.”

It usually took about an hour to form a full wing of three groups, totaling at least 60 planes. Air divisions of three or more groups took more time to form, until several hundred heavy bombers were circling over East Anglia, an area as large as Connecticut.

A later innovation was the “assembly plane,” usually a retired B-24 with all its armament removed and painted garish colors to make it highly visible to the bombers. Using flares and other visual recognition signals, the yellow, orange, and red Liberators herded the groups into their position in the stream.

Yet, even with radio silence, the huge armada was no secret to the Germans. Radar had begun to pick them up as soon as the planes reached 10,000 feet. Radio calls went out among the Luftwaffe Defense Zones and possible targets.

Then the bombers turned southeast toward the Channel and the Reich.

Getting to Work

With the English coast behind, the gunners and navigators went to work. Joe Armanini, a 100th Group bombardier, said, “I went back to the bomb bay and pulled the safety pins on the nose and tail of each bomb to arm them. The crew tested their guns when we reached the sea.”

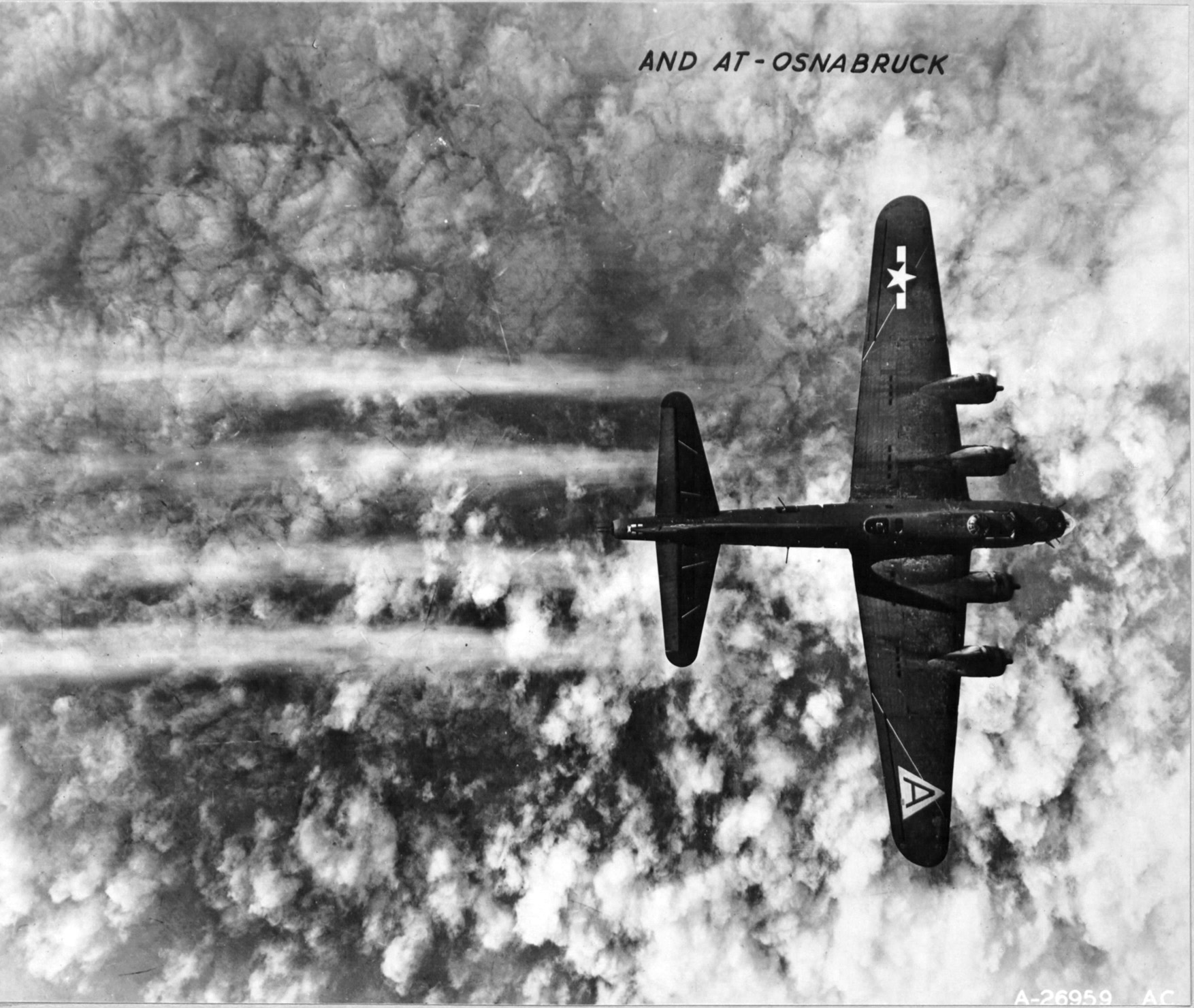

The First and Third Air Divisions were B-17 groups, while the Second Air Division consisted of the faster B-24. Most raids into Germany consisted of at least 300-400 bombers, but some of the larger raids mounted more than 800. The bomber stream ran for 50 miles from Anglia to the Dutch coast, the higher-flying Fortresses leaving long, lacy white contrails in the cerulean blue sky.

Above them flew the P-47 escorts in “S” curves to stay with the slower bombers. Far ahead, more fighters were moving over the enemy coast to suppress flak and German fighters.

Coordination between the fighter and bomber groups was one of the most difficult and often frustrating parts of a deep-penetration mission. Fog or bad weather over a fighter base might ground the fighters, but the bombers would not know of it. They expected to be met by the long-range P-51s as they moved deeper into Germany. But those fighters were not there to stay with the bombers; they were to find and destroy the Luftwaffe.

As they climbed ever higher, the crews hooked up their oxygen lines; there were emergency “walk-around” bottles if they had to leave their station. The air temperature at 30,000 feet often dropped to 40 or 50 degrees below zero.

Dick Tyhurst related how the crews endured the crippling, and even deadly, cold: “We had these heated flight suits, the F3. Regular flight suit first, then the blue, electrically heated long johns. They had a six-foot cord to plug into your station. The cuffs had cords to plug into boots and gloves. The leather pants were like overalls with a fleece-lined leather jacket.”

It was dangerous to wet oneself in the suit, as the wires shorted out and caused severe burns.

“In the older B-17Fs, the waist windows were open,” commented Rich Tangradi. “It got colder than hell in there.”

Ball-turret gunner Bob Mathiasen, a veteran of 35 missions with the 100th, said, “I had my suit temperature turned up all the way to keep from freezing to death. I never touched anything with my bare fingers. My skin would freeze onto the metal.”

The navigators, following their notes from the briefing, checked their charts and took sightings on landmarks. Lieutenant Hal Turrell, navigator in the 445th Bomb Group said, “A navigator never knows where he is. He knows where he has been, and where he is going to be, but never where he is.”

Flak: The Black Death

As the bombers crossed the North Sea, they entered the domain of German flak batteries that were often positioned on bomber routes. Fliegerabwehrkanone, meaning aircraft defense cannon, was one of the most feared and despised defenses the bomber crews faced. This Krupp-built 88mm gun could effectively reach up to 25,000 feet, causing the bombers to fly into a deadly umbrella of hot shrapnel.

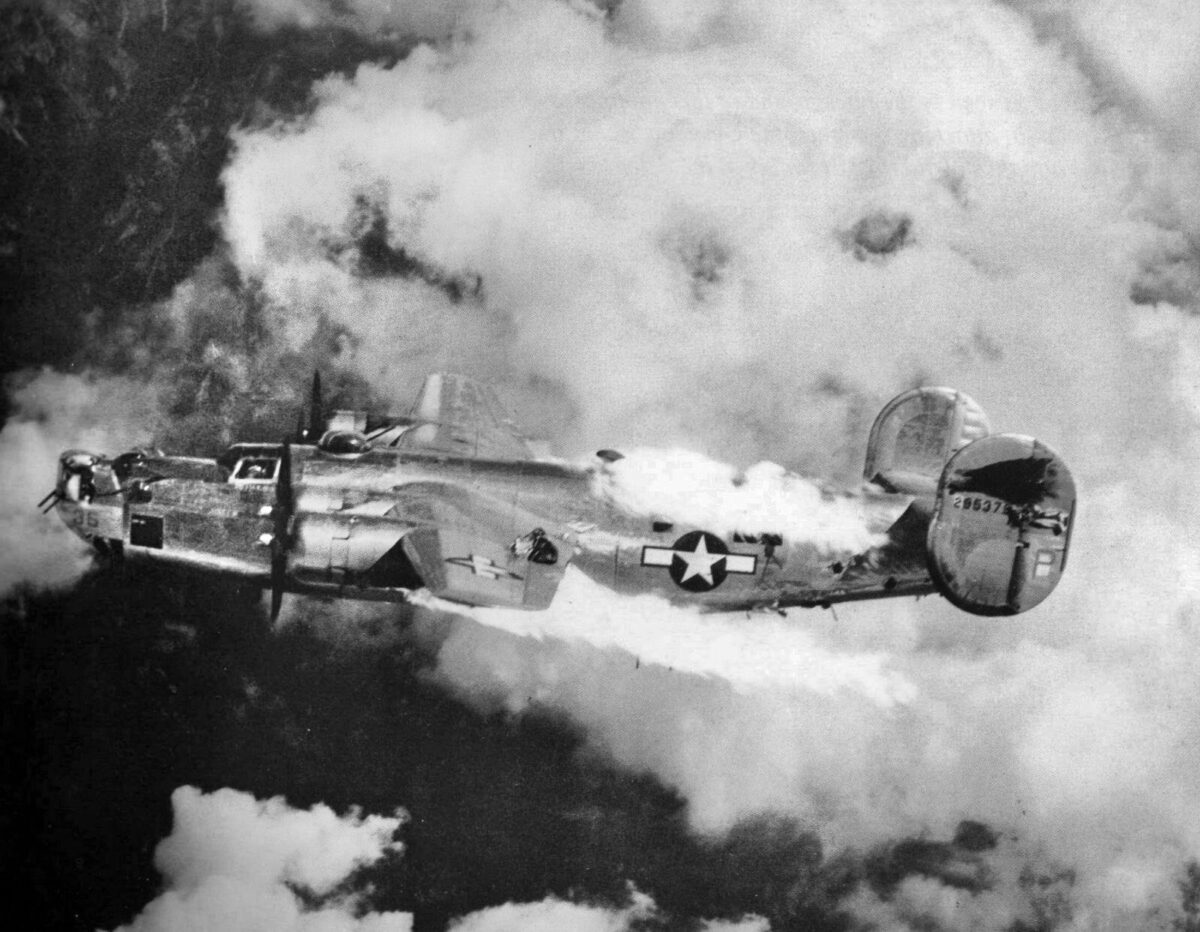

When flak burst close by, the pilots’ control wheels often shook with such violence it was difficult to hold them. Red-hot shrapnel tore through a bomber’s thin skin, ripping apart control lines, hydraulics, instruments, and human flesh. The B-17 had a reputation for being able to survive heavy damage, but still, many of them were brought down with flak. The faster, longer-ranging Consolidated B-24 Liberators could not absorb as much damage. Being lower in the formation, they bore the brunt of the flak strikes.

Pilot Stephen King of the 379th Group recalled, “We were briefed that there were over 900 flak guns at Hamburg. I believe it.” Sergeant Bruce Richardson, a 35-mission tail gunner with the 100th, commented, “Merseburg had about 1,100 guns, nearly all 88s.”

“The Germans put 88s on railroad cars so they could move them to where they were most needed,” said 384th group pilot Bill O’Leary. “Crews talked about flak so thick you could walk on it. The sky over Cologne was almost black. I don’t know how any planes made it through. We came back with an awful lot of holes.”

Rip Reopelle said laconically, “If anybody who went through flak said they weren’t scared, they’re a liar.”

Dick Tyhurst recalled, “When I saw the flak over Munich, I thought ‘Wow, unless we’re lucky as hell, we’re gonna get killed.’ Life got pretty serious all of a sudden. The 88 had a range of over 25,000 feet. Fortunately, we flew above that. The gunners were so good that if you flew below 20,000 feet you were duck soup.”

Waist gunner Frank Buschmeier of the 100th said, “The Germans fired volleys hoping we’d fly into it. It preyed on our mind more than fighters because there wasn’t anything we could do about it.”

During the period from fall 1943 to spring 1944, an average of 30 bombers were shot down on every mission over Germany. With each plane went 10 young men.

Joe Armanini related an encounter with flak: “Over Berlin the flak was fierce. If you saw the red ball in the center of the flak, that was really close. One exploded, couldn’t have been more than 10 feet away, and it just shook the whole plane like hell. I said ‘God, that was really close!’”

What flak could do to a plane was made clear to Don Hammond: “On one mission I was bent over getting a chaff roll to eject through the window chute. When I came back up and saw the fuselage, there was a huge hole right where my head had been.”

“I lost my radio operator over Germany,” John Gibbons said. “An 88 exploded in his compartment and blew him out, leaving only a six-by-eight-foot hole.”

Bombers loaded with fuel, ammunition and four tons of high explosive often blew up from a direct hit to the bomb bay.

Lt. Col. Bierne Lay, Jr., who in 1948 would co-author the screenplay for “Twelve O’clock High,” starring Gregory Peck, was an observer with the 100th on the August 17, 1943, mission to destroy a Messerschmitt factory at Regensburg. The appalling casualties of the Schweinfurt-Regensburg mission are well known, but Lay’s accounts are worth noting: “A B-17 turned slowly to the right out of the formation, maintaining altitude. In a split second the B-17 completely disappeared in a brilliant explosion from which the only remains were four small balls of fire, the fuel tanks, which quickly consumed as they fell earthward.

“I saw one B-17 with its cockpit completely on fire. The co-pilot crawled out of his window, held on with one hand, reached back to buckle on his parachute, let go, and was whisked back into the horizontal stabilizer. I think the impact killed him. His chute did not open.”

Far below, the green fields and forests of Germany bore dozens of black funeral pyres, the wreckage of the bombers brought down.

“Bandits at 12 o’clock high!”

By the end of the war, antiaircraft fire had brought down more than 5,400 bombers, compared to 4,300 claimed by fighters. But the Me 109 and Fw 190 were the deadly sharks in the aerial seas over Europe. Nevertheless, bomber crews preferred dealing with fighters because at least they could shoot back at their foe.

Early in the war, the Luftwaffe was cautious of the bristling guns of the B-17s and B-24s. But in time, they found chinks in the coverage of the machine guns. The weakest spot on both the B-17 and B-24 was the nose. The few flexible .30-caliber guns in the nose compartment—operated by the navigator and bombardier when they were not involved in their primary duties—were not able to do more than annoy the darting fighters. Along with the twin .50s in the top and ball turrets, they were the only guns that could be turned to face a head-on attack.

On November 23, 1942, an audacious and daring Luftwaffe pilot named Egon Mayer of III JG 2 Richthofen shot down two B-17s and one B-24. He developed the tactic of moving about five miles ahead of the bomber stream, approaching head-on at a combined speed of about 550 knots, and firing a three-second burst of cannon fire into the bomber’s nose and flight deck. Mayer’s success soon led to more head-on attacks, and by the spring of 1943, it was a standard tactic for the Luftwaffe.

The Luftwaffe’s primary fighter weapon was the 20mm cannon, which was used on all its front-line fighters. While they had a slower rate of fire than machine guns, their explosive shells could do terrible damage to an unarmored bomber.

A 91st Bomb Group co-pilot watched as a B-17 was completely cut in two by intense 20mm shells: “The B-17 came apart at the radio room. The front half, wings and engines still running, seemed to rise, completely separated from the tail. Debris fell away, then the two halves twisted and tumbled down and away.”

Unlike the flexible guns used by the waist and nose gunners, the top and belly turrets were physically mounted to the bomber’s frame. When fired, they shook the entire plane with solid thumps.

Navigator Edwin Frost of the 381st Bomb Group said, “It was just pandemonium!

It seemed that every gun on the ship was firing at once. The noise was terrific. The Germans were just tear-assing right through us.”

The B-24s of the 445th Bomb Group went on their first mission on December 13, 1943, to hit the submarine pens at Bremen and Kiel. By this time Bremen was protected by over 350 AAA guns and 100 fighters.

One of the B-24s was piloted by movie star and Captain Jimmy Stewart, who would fly at least 30 missions with the 445th. Navigator Hal Turrell recalls that mission and his first encounter with Hermann Göring’s fighters: “We met up with German fighters over the North Sea.

“They came diving in on us from 12 o’clock high; our combined speed was 550 miles per hour. These Luftwaffe pilots were very aggressive and experienced. They came right through our formation, firing and rolling on their sides.

“I remember thinking, ‘Lord, it isn’t like the movies. Where is John Wayne?’ Then a P-38 Lightning came diving through our formation, and I thought, ‘Great! The cavalry’s arrived!’ Then I saw an Me 109 on its tail. Just about the time he came level with us, the P-38 exploded. So much for the cavalry.

“Bombers went down by falling out of the sky, either burning or spinning. When this happened, there were rarely any chutes. The poor guys were pinned against the walls by the centrifugal force and never got out. They rode those doomed planes right into the ground.”

Lieutenant Ralph Golubock was a replacement co-pilot in the famous 44th Bomb Group, the “Eight Balls,” which had flown the disastrous August 1, 1943, low-level raid on Ploesti, Romania. (See WWII Quarterly, Winter 2019.) With the group back in England by the fall of 1943, Golubock was on his first mission on December 30 to hit the I.G. Farben plant at Ludwigshaven, deep inside Germany. The German fighters attacked shortly after the Eight Balls crossed the coast.

“We could see them queueing up far ahead of us, and soon they started coming in directly ahead, slightly above our altitude,” Golubock said. “They dived straight in at us, firing the whole time, until I thought they were going to ram us.”

One of the co-pilot’s duties was to call out the fighters, but Golubock found this to be nearly impossible. “I did my best, but they were coming in from all over and flashing past before I could even say anything. All of our guns were firing, and the smell of cordite permeated the plane.”

Aerial Arsenal

The period between October 1943 and January 1944 was almost a respite for the Eighth Bomber Command. While they licked their wounds, new groups and replacement planes came in from the States. The big change came on January 6, when General Jimmy Doolittle replaced Ira Eaker as head of Bomber Command. The leader of the April 1942 raid on Tokyo had inherited a rapidly growing force that was both veteran and neophyte, with an expanding list of targets and objectives.

Operation Point Blank, the eradication of the Luftwaffe, which began in July 1943, was still in effect, but the looming invasion of Europe set for late spring 1944 was going to require a different set of priorities in Germany and France. Still, Doolittle’s bombers went on missions, often suffering appalling losses from flak and fighters.

Rich Tangradi recalled, “I spotted an Fw 190 coming up out of the overcast inching in towards us. I thought, ‘You sonofabitch, when you get to about 600 yards, I’m gonna get you!’ He came in and I hit my triggers—and my guns didn’t work. He got to about 200 yards and started shooting. The Focke-Wulf has guns in both wings and the shells were going by on each side of me. I got hit in both arms. It’s a good thing it wasn’t an Me 109 because they have a big 20mm in the nose. If he’d had that, he’d have blown me away.”

Doolittle was planning on leading the first mission on “Big B,” as Berlin was known. But his knowledge of the upcoming Normandy invasion and the cracking of the ULTRA encryption system made it too dangerous to allow him to fly over enemy territory.

Berlin was the target on March 4, with 500 B-17s from the First and Third Air Divisions sent aloft. This was to be a mission to hit the heart of the Reich, but false German radio signals caused much of the Allied force to be recalled. Somehow, though, two squadrons of the 95th Group and one squadron of the 100th did not receive the recall order; even when they saw the rest of the force turning back, the 29 bombers flew on.

Lieutenant Bill Charles of the 95th saw that their combat box was in for a rough time. “We watched as vivid red flashes of AAA marked the Berlin defenses. Seconds later the heavy 88mm shells reached us, exploding among the bombers.”

The only saving grace was the presence of P-51 Mustangs that had chosen to stay with the remaining bombers. In all, the first-ever USAAF bombing raid on Big B lost five B-17s and four Mustangs. But it was only the beginning.

Two days later, Doolittle put up 700 heavy bombers and 800 fighters to hit Berlin again. The bomber stream stretched for 60 miles, leaving long contrails behind them.

The Luftwaffe countered with 500 fighters. Doolittle’s Thunderbolts and Mustangs brought down 87 German fighters, with 75 bombers lost. The Bloody Hundredth was savaged, losing 15 planes.

By spring 1944 the B-17G, with the new chin turret, was appearing in greater numbers. The chin turret, with twin remotely operated .50s, was the USAAF’s answer to the head-on attack. Still, hitting a small fighter in the few seconds that it was visible coming head-on at 550 knots was almost impossible.

Bombardier Joe Armanini said, “I preferred the older F model with the two side and nose guns. That chin turret was kind of hard to aim. I really liked being able to see down the barrel to fire the guns.”

Secret Weapons

Despite the extended Point Blank offensive, the Luftwaffe was still receiving fighters from their factories, and they had about 2,500 fighters stationed in Western Germany to defend against the bombers. Forests of flak batteries lined the bomber routes. Raids from September 11 to 13 resulted in 125 bombers shot down, but by this time fuel shortages had drastically cut into the Luftwaffe’s training of desperately needed pilots.

Their new crop of fighter pilots was going into battle with less than 100 hours of flight time, while they were up against veteran American and British pilots with more than 300 hours of training in addition to combat time.

A flight Engineer of the 381st Group recalled when four Focke-Wulf 190s came at his plane’s tail, “so close together they looked like one airplane. The greenest German pilot should have known better. But they kept on coming. Every top, ball, and tail gun poured a heavy barrage into those fighters. The storm of machine gun bullets exploded the Fw 190s in four puffs of black smoke, and the sky was filled with debris.”

Germany’s desperation was apparent when it began using unguided air-to-air rockets in the late summer of 1944. Weighing about 500 pounds and seven feet long, the rockets packed a deadly punch when they hit a bomber. They were used in large numbers on the October 10 raid on Münster. More than 30 Me 110s lined up behind the trailing planes, the 390th Bomb Group, just beyond range of the .50s, and fired at least 70 rockets at the formation. Two B-17s exploded from direct hits and a third collided with the flaming wreckage.

The hard-pressed Luftwaffe had also introduced a variant of the Fw 190. Squadrons called Sturmstaffeln or “Assault Squadrons” used the Fw 190A8, specially designed to kill bombers. Armored with bulletproof canopies and protection around the engine, the fighter had twin 13mm machine guns and four 20mm cannon.

With Me 109s flying cover over their slower and less maneuverable comrades, the Sturmstaffeln pilots would move in on a bomber’s tail, ride out the bullets coming from the tail gunner, then hammer the bomber at close range. If all else failed, the Sturmstaffeln pilots were told to ram. Some actually did.

By then, German fighters even flew among their own flak to reach the bombers. “German fighters would almost never attack in their own flak,” said King, “but over Berlin they came right into the flak and hit the bombers. Most of the time we had either flak or fighters, but this time it was both at once.

“A fighter was approaching from 12 o’clock level and I didn’t hear anything from my top turret gunner, Ray Wheeler. I got on the interphone and yelled ‘Ray, why aren’t you shooting?’ He said, ‘I’m waiting until I can get a good bead on him.’ I yelled ‘Goddamnit, scare him away!’ Ray was credited with five enemy aircraft. He joked that if he’d been a fighter pilot, he’d be an ace.”

“Over Berlin the fighters came into their own flak,” said ball-turret gunner Bob Mathiasen. “I looked forward and saw at least 200 fighters coming at us. We lost lots of planes on that mission. I got a confirmed Fw 190. He was coming up and I zeroed in and got him in the cockpit.”

Ball gunner of the 91st Group Dan McGuire said, “I got two Me 109s at once. I put about 200 rounds into one and finally he lost control. He plowed into another fighter and they both went down. I learned this after the mission when a waist gunner said, ‘Hey you got two of them.’ I wasn’t credited with either, though.”

Gunners’ claims were often exaggerated but with good reason. Scores of gunners fired at each fighter and when one went down, several claimed it.

“Later we read in the papers that we’d shot down 400 German fighters,” Armanini chuckled. “Crap, if we’d been that good there’d be no Luftwaffe left.”

Friendly-fire losses were inevitable when hundreds of heavy machine guns filled the sky with hot lead as the gunners tried to track and intercept the wheeling fighters. It was often impossible to avoid hitting another bomber.

Sergeant Bill Fleming of the 303rd Group recalled a disturbing incident in the fall of 1943. “Lieutenant Stockton flew on every mission. Instead of taking passes, he flew.” On Stockton’s 24th mission, with only one to go to finish his tour, he was killed. The official report was that he had been killed by a German 20mm shell. But the truth, never made public, was that Stockton died from an American machine-gun bullet.

B-17. With their limited range, the P-47s could not accompany the bombers to distant targets, but

P-51s could.

Little Friends

At last, the bombers were being escorted all the way to the targets by P-47s and P-51s. Doolittle still ordered that they make the destruction of the Luftwaffe on the ground and in the air their top priority, which secondarily made life easier on the bomber crews.

Bombardier Armanini related one encounter with a P-47 Thunderbolt: “We were supposed to bomb the Ruhr, but it was overcast, so I saw this factory with a tall smokestack, and I made a run at the target and we creamed it. I saw this Focke-Wulf coming at us and then this Thunderbolt was hammering at him and shot him down.

“Later on, I was at the Officers’ Club having a drink and this guy comes in and asked, ‘Hey who was the guy who bombed that factory?’ I said, ‘That was me.’ The guy turns out to be Francis ”Gabby” Gabreski, a top ace. He said ‘Joe, I gotta tell you that was the best bombing I’ve ever seen.’ Real nice guy. He saved our butts and he’s congratulating me.”

Ball gunner Bob Mathiasen also praised the fighter escort. “Those guys were absolutely great. If we were jumped by fighters and the ‘Little Friends’ came up, it only took one look and the Germans were gone.”

In the summer of 1944, the new cannon-armed Me 262 jet fighter began tearing through bomber formations, attacking with near-impunity. But the Mustangs were still there.

“I happened to look out and saw three contrails,” said Bill O’Leary. “One was horizontal and the other two were almost vertical. It was two P-51s diving to get a 262. They were never going to catch him. But I was glad they were there. He never came back.”

“Bombs Away!”

The heavy bombers’ primary job was to carry four tons of high-explosive bombs to a target in Germany. While the gunners and pilots sweated out the German defenses, the bombardiers prepared to earn their pay. The role of the flight crew and ground personnel was to get the plane to where the bombardier leaned over his Norden bombsight.

One bombardier of the 493rd Group, Lynn Tipton, described his duties as the B-17 approached the target run: “At the Initial Point I had the Norden bombsight all warmed up. The pilot gave me control of the plane, and the Norden did the flying. If you got it all dialed in correctly, you were on the straight line of your course track. Then there’s a line crossing that line. When the target passed under the second line, that was when you hit the bomb release.”

Tipton continued, “We flew in 12-plane echelons. When the lead bombardier dropped, we all did.”

Armanini also gave the Norden high marks. “If all the settings were done right and the course was correct, there was almost no way you could miss.” On one mission, a flak shell burst nearby just as he was releasing his “eggs.” “Once they were gone, they were out of my control. I closed the doors and the pilot took over.”

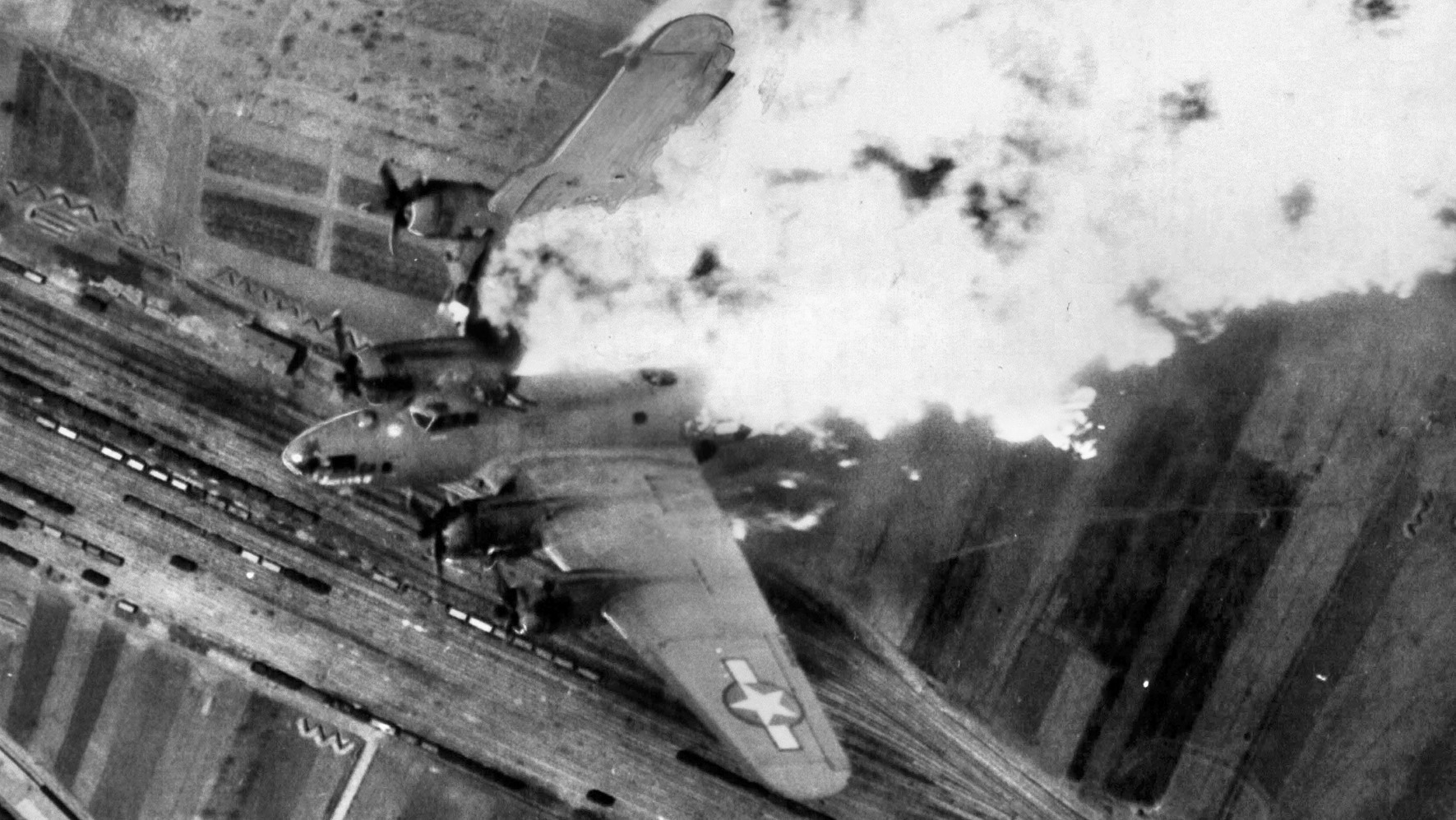

Six miles below them, the 500-pound bombs slammed into their targets, blowing off factory roofs, turning walls and windows into deadly shrapnel. From 30,000 feet, the bombs were seen as long rows of white and yellow flashes and sprays of smoke and debris. The sound went unheard among the heavy drone of engines. But as careful as the raid had been planned and executed, most of the Eighth Air Force’s tens of thousands of bombs missed their targets, exploding in streets, fields, forests, farms, and homes. Germany’s war industry was far from being destroyed.

The Stormy Return

As the shriek of the falling bombs diminished, the crews had done their job for Uncle Sam, as they said. “Then we were flying for us,” said Tipton with a chuckle.

The route back to England was often different from the approach to the target, but it was no less hazardous, especially after a successful bombing. That was when the German fighters came for blood.

Waist gunner Frank Buschmeier remembered, “All of a sudden our tail gunner was firing. I looked and there was this Messerschmitt, and he was right behind the stabilizer. I couldn’t get a shot. He hit us without anybody being able to shoot at him. The radio operator was right next to me, not 18 inches away. One shell hit me in the right leg, and one hit him in the jugular vein, and he dropped dead right there. A big pool of blood spilled and froze on the deck.”

Tail gunner Tangradi talked about his last mission: “The fighter that hit my arms tore us up pretty good, and the engines were smoking. I crawled forward and called waist gunner Willy Kemp and asked him to help me with my chute. The blood was running down my wrists and hands. I told the other waist gunner to go forward and find out what the hell was going on. He came back and said, ‘The guys up front were all gone.’

“I figured the plane was so shot up that the bailout bell didn’t work. The radio gunner was hit, his face was all bloody, his fingers were frozen, God, like 10 white candles. The ball turret gunner’s elbow was blown away. We kicked the door out and jumped. And Willy Kemp, the kid who helped me put the chute on, went down with the plane. It went into a spin and he got caught inside in the centrifugal force.”

Bombers already damaged from flak and earlier attacks were enticing targets, and many fell from the skies to turn into flaming smears of debris.

Bombardier Lynn Tipton recalled of his last mission, “The plane was shot to pieces, all four engines were out. The co-pilot said, ‘Bail out!’ The pilot was dead. We just dove head-first through the nose hatch. The ball gunner was still in the plane and it suddenly exploded and he fell with all that debris, but he lived.”

Pilot Stephen King had a similar experience: “On my last mission over Hamburg, we were at 29,000 feet when we were hit by an 88 in the nose. Suddenly we took another big hit on the right wing. The engineer said, ‘Hey, the right wing’s on fire!’ I looked out past my co-pilot and the whole right wing was burning like mad. There was no way to stop it. I rang the bail-out bell and the navigator, bombardier, co-pilot, and flight engineer went out the nose hatch.

“I checked to see if the rest of the guys in the back were out. I put my chute on and looked back through the bomb bay. The radio operator was staring out the open bomb doors with a panicked look on his face. The gunners in the back were still in the plane. Just then the plane blew up around us. As far as I know, the only survivors of the explosion were me and the ball-turret gunner. The others were killed.”

Falling from over 29,000 feet, airmen were told not to pull the ripcord until they were at around 3,000 feet. German fighters sometimes shot at men hanging helplessly under parachutes.

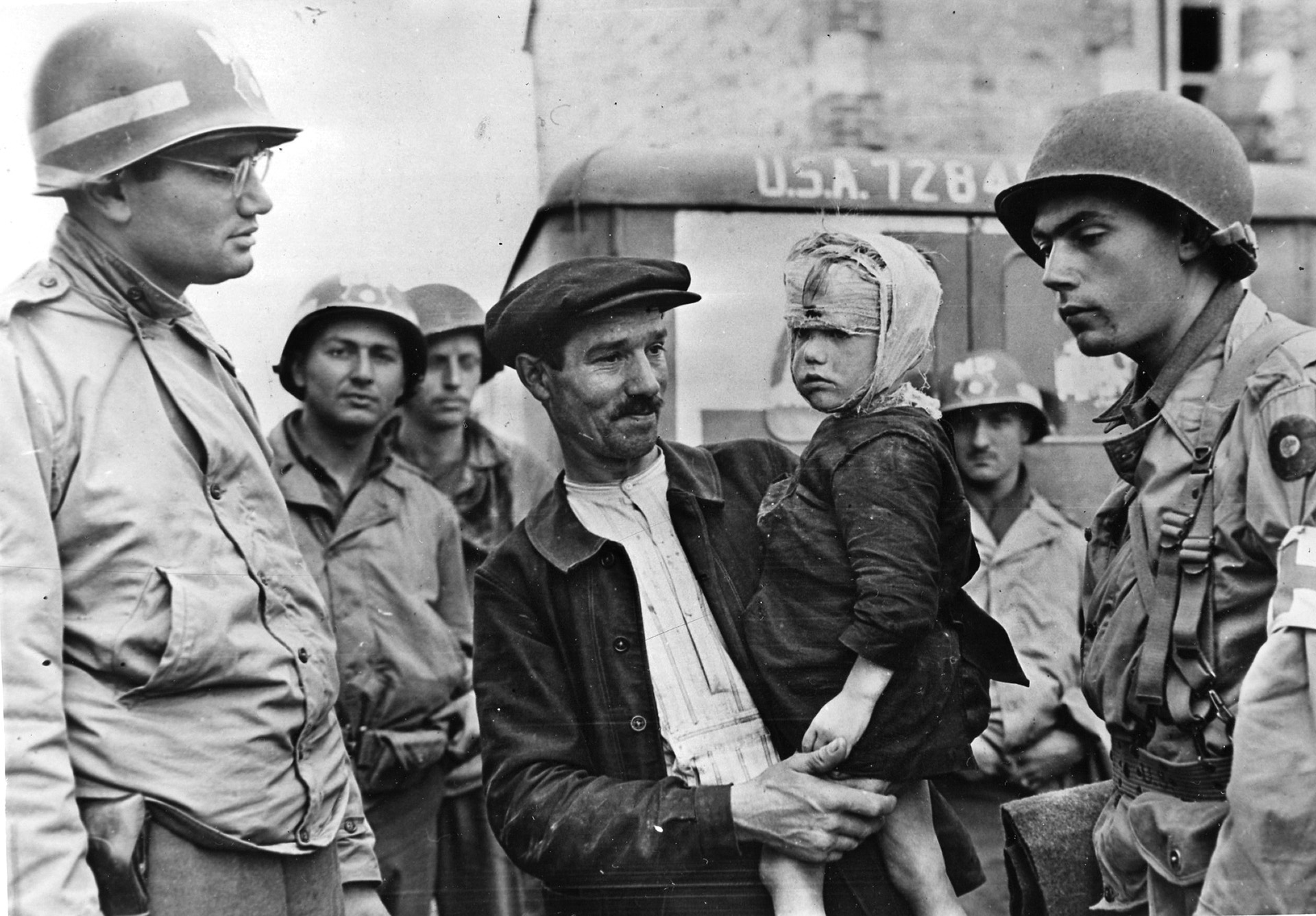

The heavy drone of the bombers and the snarl of fighters, the chatter of machine guns, and the thump of AAA and cannon faded into the distance as men fell under silk parachutes onto a land populated by angered civilians and patrolling German soldiers.

The lucky ones who bailed out over Holland, Belgium, or France were often picked up by the Resistance or sympathetic civilians to be hidden from the Germans until they could be returned to England. But most ended up in POW camps to begin a new and bewildering time in their lives.

Bushmeier said, “I landed in a river and the Home Guard were taking me away, and this same fighter flew over and waggled his wings. I never figured out what he meant by that—if he was saluting another airman or he was just saying ‘Hey, I got you.’”

For the bombers able to elude the maddened German fighters and coastal flak, the blue waters of the North Sea and English Channel were a beacon of hope.

“One thing we never did was to secure the guns until we were over the base,” said Ed Davidson. “Some planes were hit by German fighters even when they were over the Channel. If a plane had wounded aboard, they fired a red flare and got priority for landing.”

When the battle-scarred bombers reached their revetments and the propellers stopped, it was eerily silent. For the first time in nearly a dozen hours the noise of the engines and hammering guns was stilled. The tired, heartsick crews picked up their gear and gratefully stepped onto Allied soil. The grassy loam of the surrounding fields turned golden in the setting sun.

Many men watched as more planes landed, mentally counting, hoping all would return. But, for many crews, memories of burning planes and drifting parachutes told the hard truth. Cigarettes were lit by shaking fingers.

“We went to debriefing,” Davidson explained. “Every man was taken aside to speak to an intelligence officer and tell what we saw. Everyone was given a shot of whiskey to loosen his tongue.”

Rip Reopelle went one better. “We got brandy for our debriefing.”

In the mess hall of a group that had a successful mission, talk was often spirited, but for a unit that had lost many planes and comrades, the clink of forks on metal trays was often the only sound. A few men could not eat at all and had to be urged by their buddies. Cigarettes and a walk in the evening was often the only way to cope. Some visited the infirmary to see wounded friends.

Stephen King said, “It was hard to see men wrapped in bandages or with arms and legs gone. But at least they were alive.”

When the weary crews bedded down for the night, often with empty cots beside them, they knew it was not over. The next day or the day after that, they would once again be awakened to do it all again.

Super article must be more info on the plane needs to have more history on this plane