By Peter McQuarrie

The Battle of Tarawa, a component of Operation Galvanic, was the U.S. Marines’ first bold amphibious assault against a Japanese stronghold in World War II. Many lives were lost and many lessons learned, on both sides.

There have been many accounts of the battle, the strategic and tactical considerations and the logistics of staging a major battle on a coral atoll in the center of the Pacific. But all of the accounts have been written in English from the American perspective. This article tells the story of the Battle of Tarawa from the Japanese perspective.

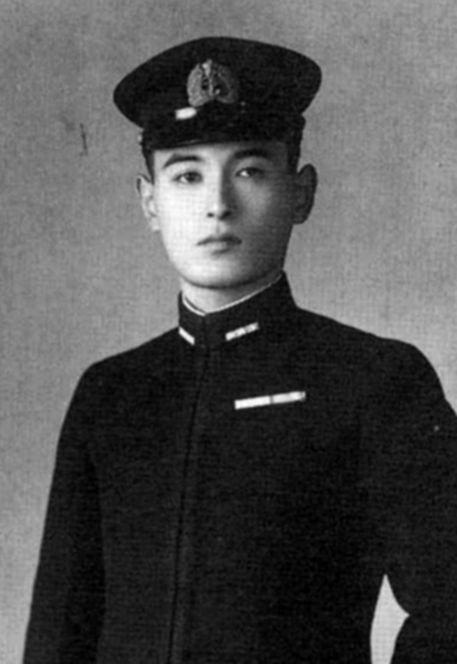

Few of the Japanese who took part in the battle survived to tell their stories, and our information comes largely from one person, Taniura Hideo. A lieutenant in the 6th Defense Force at Kwajalein, Marshall Islands, he led a Special Naval Landing Party (SNLP) to occupy Tarawa in August 1942. He then returned to Tarawa in March 1943 as commander of the Sasebo 7th SNLP, which had been formed in February, and was involved in the base development work on the islet of Betio at Tarawa atoll.

Three months before the Battle of Tarawa, Taniura returned to Japan. After the war, he had a career in the Japanese Self Defense Force and retired in 1969 with the rank of rear admiral. During his years in the Self Defense Force, he interviewed his Navy colleagues who had been with him on Tarawa, those who had left the island when he did, and others who stayed longer. A few had remained on Tarawa and survived the battle. Taniura recorded information from their stories in his memoir, published in Tokyo in the year 2000. This provided much of the information for our story.

On November 8, 1943, a heightened state of alert was issued to Japanese bases in the Central Pacific. The concern was due to the greater degree of American activity in the area. The Japanese on Tarawa had noticed that there had been an increase in the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) bombing raids by Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers against the Gilbert Islands, Nauru, and islands to the north, in Micronesia. The atoll of Maloelap, 530 miles north of Tarawa in the Marshall Islands, had been targeted by B-24s, and was so again on November 14, 17, and 18.

The recently built U.S. airbase at Nanumea, the northernmost island in the Ellice group, had become operational for B-24s on November 12, and this more northerly base increased the bombing range of aircraft staging through Canton Island, Funafuti, and now also Nanumea. It brought some Marshall Islands targets into range. The Marshall Islands of Mili, 330 miles from Tarawa, and Jaluit, a similar distance away, had also been attacked.

At the time, the Japanese on Tarawa thought that their Gilbert Islands bases might be bypassed in any invasion. They believed it was likely that they would be neutralized by regular USAAF bombings and that an invasion would first be made in the Marshalls, perhaps at Maloelap. Finally, however, from the early morning of November 19, carrier-based aircraft and USAAF heavy bombers attacked Tarawa and Nauru and it was realized that Tarawa or Nauru, perhaps both, would be invaded. Nauru had poor landing areas for an invasion from the sea, so the U.S. Marines made no attempt to land there. Nauru would instead come under siege, and the Japanese there would be starved into submission.

When the air bases at Jaluit and Maloelap sent out surveillance planes to search for enemy shipping near Tarawa, they reported a group of aircraft carriers south of Nauru and another fleet of ships southwest of Tarawa. There was also a group of transport vessels east of Abemama Island. All these ships were heading in the direction of Tarawa and it was now clear that the target of the invasion would be Betio Islet, Tarawa. The commander of the Tarawa garrison, Admiral Keiji Shibasaki, sent out an urgent message advising that three cruisers and five destroyers had been spotted heading for the island.

It is clear that Shibasaki did not expect to receive any assistance from the Imperial Japanese Navy in defending Tarawa against any U.S. attack. In May, before Shibasaki arrived at Tarawa, Taniura and other senior officers from Tarawa had attended the Inner South Pacific Strategy and Defense Conference, held at Truk in the Caroline Islands. The conference attendees had been told that the Japanese situation had turned from one of offense to that of defense. The Tarawa defenders’ mission was now to delay as long as possible the Allied advance toward Japan, using all means available to them. When Shibasaki had been posted to Tarawa in July, he well knew that it was a suicide mission and that he would receive little support from the navy.

About an hour after Shibasaki had sent out his message, a bombardment by USAAF B-24s began. Tarawa and Nauru came under attack, and at Tarawa the USAAF attack was followed soon after by another with planes from the aircraft carriers. Nauru and Tarawa both suffered considerable damage from these attacks on November 19, but this was just the beginning of much more that was to follow the next day.

Most of the wooden buildings were destroyed outright or burned down during the attacks on the 19th. Deaths and injuries on Tarawa resulted from explosions of ammunition or fuel dumps, or from direct bomb blasts, and there was considerable loss of life. The Japanese were, however, well satisfied with the performance of their coconut log and sand bunkers and steel pillboxes, in that they withstood the bombings. Kiyoshiso Ota, who survived the battle, was in the Transport Division of the Sasebo 7th Special Naval Landing Force, the force which had been led to Tarawa by Taniura. He reported that where he was stationed, in a pillbox close to the base of the main wharf, up to 50 percent of the personnel died. In other areas on Betio the estimate was 20 percent.

An attacking squadron of a few Japanese planes from Jaluit fought back, but only two of these planes discovered the American ships. One plane was shot down, and the other scored a bomb hit on one of the carriers, apparently not causing serious damage. Bomber aircraft were parked at Betio airfield after a raid on Funafuti the night before, and most of these had received slight damage during the Funafuti raid. More damage resulted from the USAAF attack, and the surviving aircraft were repaired on the night of the 19th.

Before dawn on November 20, 1943 (D-day at Tarawa), some planes and aircrew were evacuated to bases in the Marshall Islands. Seven bombers remained to defend Tarawa. Of these seven planes, only two returned to Tarawa after setting out to attack the American fleet on the morning of November 20.

At dawn on the 20th, a fleet of US ships could be seen from Betio, approaching from the northwest. A battleship commenced firing at Betio and the southwest 20 Santi gun (the 200mm, or 8-inch Vickers gun), replied. A short time later, two minesweepers entered the lagoon, and the Japanese then knew for certain that a landing would be made from the north, on the lagoon beaches of Betio, the beaches now known to history as Red Beaches 1, 2, and 3. The guns along the south coast, 7 and 14 Santi guns (70mm infantry guns, Model 92 and 140mm coastal defense guns), were turned away from protecting the ocean beaches in the south to point toward the U.S. fleet in the north. At least one of the southern guns was removed and dragged manually across the airfield to the Seven Specials Headquarters, on the north coast, where it was remounted.

The Japanese record states that they also had a small-caliber Russian gun installed in a turret housing on the south coast and that this installation was also moved to the north coast. However, there does not appear to be any mention of Russian guns in any of the U.S. after-action accounts of Tarawa, and this gun may have been completely destroyed in the battle.

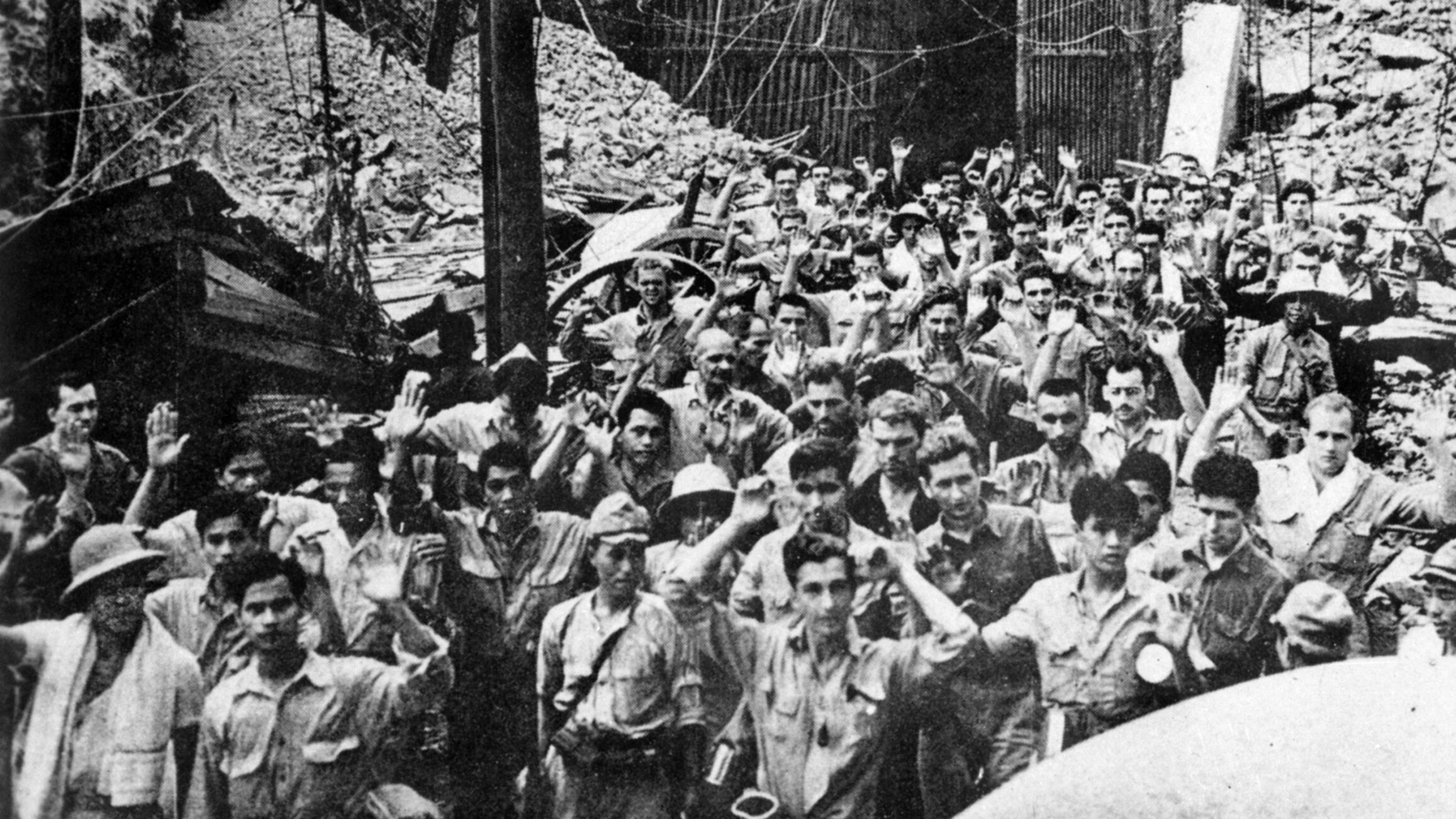

Marines began invading the lagoon beaches in their boats and “scorpion vehicles” (amtracks or LVT landing craft), and the Japanese had success in shooting some of these vehicles, destroying many of them and killing many Marines before they made the beaches. But even under heavy fire, the Marines kept coming, wading through the shallows, stepping over the bodies of their fallen comrades.

The Japanese were overwhelmed by the sheer numbers. Their bunkers and pillboxes that had protected them from bombs and the 16-inch shells fired by the battleship USS Maryland could not save them from the flamethrowers and grenades. These entered their fortresses through small apertures, observation ports, and ventilation shafts and caused carnage inside. The Japanese had their own grenades and flamethrowers, but these were far less powerful than the American ones and fewer in number. Flamethrowers and grenades were formidable weapons for the Marines’ assault but not useful for the Japanese in defense. The Japanese had few flamethrowers at Tarawa and as far as is known, they were never used in the battle.

In regard to the actual battle, the strategy and tactics involved and how they played out, the Japanese accounts have little to say. The survivors were individuals with limited personal experiences of the fighting; they were not involved in planning. Basically, Taniura does not disagree with much that has been written by U.S. historians about the battle. He makes reference to Sherrod’s, The Story of a Battle, and mentions Tarawa’s Terrible Battle Record, by Robert Charlotte, which was translated into Japanese in 1950 by Goro Nakano. Also referenced by Taniura are Samuel Eliot Morison’s History of United States Naval Operations in WWII, and the U.S. Marine Corps account, Battle of Tarawa, by James Stockman.

One matter which Taniura comments on is the number of Japanese defenders at Betio. He affirms that the U.S. method of estimating the number of men based on the number of reef latrines seen in aerial photographs did give an accurate figure of approximately 4,500. But he feels that often it is assumed that all these people were elite Naval Land Forces. In fact, approximately 2,000 of these men were unarmed workers, Japanese or Korean civilians with the 111th Encampment Corps and the 4th Construction Department. It is believed that there were approximately 100 Koreans on Betio at the time of the attack, only 25 of whom were captured alive. For the concurrent American seizure of Makin we have an accurate figure for the number of Koreans, obtained from Korean sources. There were 414 Korean civilian workers at Makin, and 104 of them survived the battle. So, of the total of 4,500 men on Betio there were 2,500 who were trained and armed fighters.

Taniura sheds light on the roles of the Japanese who died in the northern area of Tarawa. In the mopping up operations after the battle on Betio, American forces moved along the atoll to the east and then made their way north toward the extreme northern tip of the atoll at Naa. As they approached Naa, they encountered a group of 164 Japanese armed with mortars, machine guns, and rifles. Fighting began and continued until all the Japanese were killed, with the exception of one Japanese and one Korean, who were captured. U.S. casualties were 34 Marines dead and 56 wounded. It has previously been thought that the majority of the Japanese encountered at Naa were fighters from South Tarawa who had fled north during the battle. Taniura informs us that two coastwatching stations had been set up on Tarawa by the Japanese, one in Buota in the east and the other at Buariki in the north. They were sited at these locations to allow them to quickly detect and report any enemy aircraft or ship approaching Tarawa from the east or north. Each station had approximately 60 staff, a communications team with light, mobile radios, a transportation team with one truck and a machine-gun car, paramedics, and administration staff. The majority of Japanese killed at Naa were members of these two coastwatch stations.

Taniura stresses that the Japanese were hugely outnumbered by a force with a massive number of superior arms, equipment, and machinery. According to Taniura, the Japanese war was fought on a shoestring budget using 1930s technology. The support of Japanese Navy, extremely afraid of using up all of its ammunition, was poor.

The Navy Land Force on Tarawa had little in the way of practical training. Each man was not allowed to consume more than five rounds of rifle ammunition per year, so there was very little practice with live ammunition. At Tarawa the Japanese were largely a force of snipers, each man hiding himself from the enemy, with a rifle and limited supply of bullets, trying to make every shot count. Their large cannon soon ran out of ammunition, and their machine guns too.”

Peter McQuarrie writes about World War II in the Pacific Islands. He has previously written for WWII History, Naval History, The Journal of Pacific History, Pacific Affairs, and Pacific Islands Monthly. His books include Strategic Atolls, Tuvalu and the Second World War (1994) and Gilbert Islands in WWII (2012).

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments