By Flint Whitlock

For a week before November 20, 1943, U.S. Navy and Seventh Air Force planes did their best to destroy the Japanese defenses on the tiny Pacific atoll of Tarawa. Along with shelling from ships on the morning of November 20, it is estimated that six million pounds of explosives hit the island before the U.S. Marines were due to land.

But on the morning of D-Day, some planned air assaults were delayed, cut short, or never took place. Military leaders were surprised to find some defenders on Tarawa had survived. A naval bombardment that lasted more than two hours took place as U.S. forces moved toward the tiny island some 40 minutes behind schedule.

The soaked, seasick Marines in the landing craft bobbing and churning on a rough sea toward their beaches were unaware of the screwed-up assault timetable. All they knew, if they could glance over the gunwales at the island ahead of them, was that the softening-up that had been promised seemed to be going well. Explosions kicked up huge plumes of water and sand and coral, and thick black smoke billowed up above the shattered palm trees.

But the full impact of the delays was about to be revealed. Invasion planners had miscalculated, missing the high tide.

The Higgins boats, even with their shallow draft, crunched to a stop on the coral reef 500 to 800 yards from shore, and the men began piling out, wading inland with streams of machine-gun bullets coming their way. The first wave of Marines was cut to pieces.

Comprised of more than 30 islets, Tarawa Atoll looks like every other Central Pacific paradise: brilliant blue waters, swaying palm trees, an abundance of colorful birds and sea life. But in November 1943, to the U.S.

Marines who were tasked with taking it, the one square mile atoll looked like hell— especially after they had been assured that taking Tarawa would be a “walk in the park” and “a piece of cake” that would only involve a few hours’ work.

The speck of land—8,000 miles from Tokyo and 2,400 miles from Pearl Harbor and Australia—looks like a nice place to visit, but not important enough to die for.

Yet, that is exactly what happened to some 6,000 Americans and Japanese (and Koreans) whose ultimate fate came together there in November 1943.

In February 1942, two months after Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Navy’s Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Ernest J. King, saw the need for America to take over as many Pacific islands as possible. He stated, “The general scheme of things is not only to protect the lines of communication with Australia but … to set up ‘strong points’ from which a general advance can be made through the New Hebrides, Solomons, and the Bismarck Archipelago.”

Lying athwart America’s supply lines to Australia, the Gilbert Islands (now Republic of Kirabati), which include Makin Island and the Tarawa Atoll, posed a problem. A Japanese presence there could threaten U.S. control of the Central Pacific.

Japanese leaders saw the Gilberts as a way to interfere with American activity in the region, and ordered the defenses there to be significantly upgraded. In December 1942, work began with the arrival of a combat engineer unit, the 111th Pioneers.

The Japanese scoured nearby islands, as Charles Gregg, author of Tarawa, put it, “for Australian and New Zealand coast watchers who, at great personal risk, had performed valiantly by providing intelligence to U.S. headquarters about [Japanese] ship and troop movements.”

A year before the invasion was launched, October 15, 1942, the Japanese, angered at American air raids in the area and a raid on Makin Island, beheaded 17 captured New Zealand and five European coast watchers.

Brought in to defend Tarawa were the Sasebo 7th Special Naval Landing Force, the 6th Special Naval Landing Force, and a 4th Fleet Construction Unit—all under the command of 49-year-old Rear Adm. Keiji Shibasaki, who famously boasted, “A million men cannot take Tarawa in a hundred years.”

He had good reason for such optimism, misplaced though it proved to be. A thousand Japanese construction workers and 1,200 Korean slave laborers had toiled for months under the broiling sun, turning the main island, Betio, into an unsinkable battleship.

There were 14 powerful 8-inch coastal guns, four of them captured at Singapore in 1941, guarding the shore. Forty other guns of varying caliber were positioned to rain fire on any approaching enemy ships, and scores of anti-aircraft guns and machine-gun nests were scattered across Betio’s 291 acres. There were also 14 light tanks, and mortars had been preregistered to drop rounds onto any attackers unlucky enough to make it to the seawall. For its size, Betio was the most heavily defended piece of real estate on the planet.

Concrete pillboxes to house the machine guns were virtually invisible—and impervious to naval or aerial assault. Barbed-wire entanglements were strewn everywhere. A four-foot-high seawall made of coconut-tree logs lined the lagoon side of the island, making it virtually impossible for landing craft to deposit troops onto a sandy beach. If any attackers made it off the beach, they would be caught in the deadly crossfire of mutually supporting pillboxes. It seems that Shibasaki had thought of everything.

Even knowing all (or some) of this, Rear Adm. Howard F. Kingman, whose ships were scheduled to bring the 2nd Marine Division ashore, declared over-confidently that the Americans would not just destroy Betio but would obliterate it. Kingman’s plan was to pummel Betio and its defenders into submission using the combined power of B-24 bombers based in the Ellice Islands and his naval guns mounted on three battleships as part of Task Force 53: Colorado, Maryland, and Tennessee. To this would be added squadrons of fighters and dive bombers from the carriers Bunker Hill, Essex, and Independence. Five cruisers and nine destroyers would also add the weight of their munitions to the slugfest.

Nothing could survive such an onslaught, believed the American commanders, in this, the first battle by American forces to seize an enemy-held island in the Central Pacific. The 2nd Marine Division could just wade ashore—if there was any shore left on which to wade. As Maj. Gen. Julian C. Smith, commander of the division, told his men, “Our Navy … will support our attack tomorrow morning with the greatest concentration of aerial bombardment and naval gunfire in the history of modern warfare.”

Unlike some of his superiors, 2nd Marine Division chief of staff Colonel Merritt “Red” Edson, who had earned a Medal of Honor on Guadalcanal, had a more realistic assessment of what faced the Marines. “We cannot count on heavy naval and air bombardment to kill all the Japs on Tarawa,” he said, “or even a large proportion of them. Neither can we count on taking Tarawa, small as it is, in a few hours.”

After the unprecedented bombardment, Smith’s Marines would head for the lagoon shore in LCVPs (Higgins boats) and LVTs (Landing Vehicle, Tracked), the latter also known as “amtracs” or “alligators,” to perform “mop-up” work.

“The amtracs were far from perfect,” wrote author Charles Gregg. “They had a prodigious appetite for high-octane gasoline…. These vehicles became unmanageable even in a mildly turbulent sea and they were difficult to maneuver under any circumstances. They had very little freeboard; even small waves washed over their low sides and soaked the waiting men. For this same reason they quickly filled and sank when stalled at sea.

“The amtracs were slow, and they had no ramp that could be dropped to let the men out. The Marines had to climb over the sides, exposing themselves to enemy fire… ” But, Gregg said, “Without the amtracs, there would have been no effective landing on Betio. Their use as assault vehicles … was one of the great tactical innovations of the Pacific war.”

The one question to which no one seemed to have had a good answer was how deep the water was in the lagoon. This answer depended on the tides. At high tide, five feet of water would cover the large fringing reef, enabling landing craft to come close to shore. At low tide, the LCVPs, despite their shallow draft, would have to disgorge their troops a long distance from shore, thus exposing them to enemy fire; only the LVTs would be able to reach shore—and there weren’t enough of them (only 125) to transport the entire invasion force.

Colonel David M. Shoup, who would command the assault force once it reached land, worried about the lagoon’s depth.

“We’ll either have to wade in with machine guns maybe shooting at us,” he told TimeLife war correspondent Robert Sherrod before the landing, “or the amtracs will have to run a shuttle service between the beach and the end of the [fringing reef].”

Impressed by the pre-invasion bombardment, and uninformed of the Marines’ strategy, Sherrod wrote, “Surely, I thought, if there were actually any Japs left on the island (which I doubted strongly), they would all be dead by now.” The correspondent, scheduled to come ashore with the fifth wave, was in for a rude awakening.

The Importance of Tarawa Betio had a fighter airstrip that, if in American hands, would provide another base from which to launch attacks on Japanese facilities in the area and provide one more stepping stone toward Tokyo.

John Wukovits, author of One Square Mile of Hell, wrote, “The Gilberts existed as part of Japan’s outer ring of defenses. An inner ring, standing closer to Japan, consisted of the Philippine Islands and other areas containing essential resources.

An expendable outer ring existed to shield the inner one from attack as long as possible, and to draw out the American fleet so the Imperial Japanese Navy could destroy it in a massive ocean engagement. The Japanese did not intend to waste reinforcements on the outer ring. They would defend it as long as possible with the forces on hand until the fleet arrived to deal with the American Navy.”

Realists among the defenders knew that the chances of the IJN coming to their rescue were slim to none, and that they were little more than sacrificial pawns whose main hope was to take as many Americans with them before they died.

Once recon flights had spotted an airstrip on Betio, American carrier planes made bombing raids on September 18 and 19, 1943, that destroyed half the Japanese planes on the ground.

D-Day at Tarawa

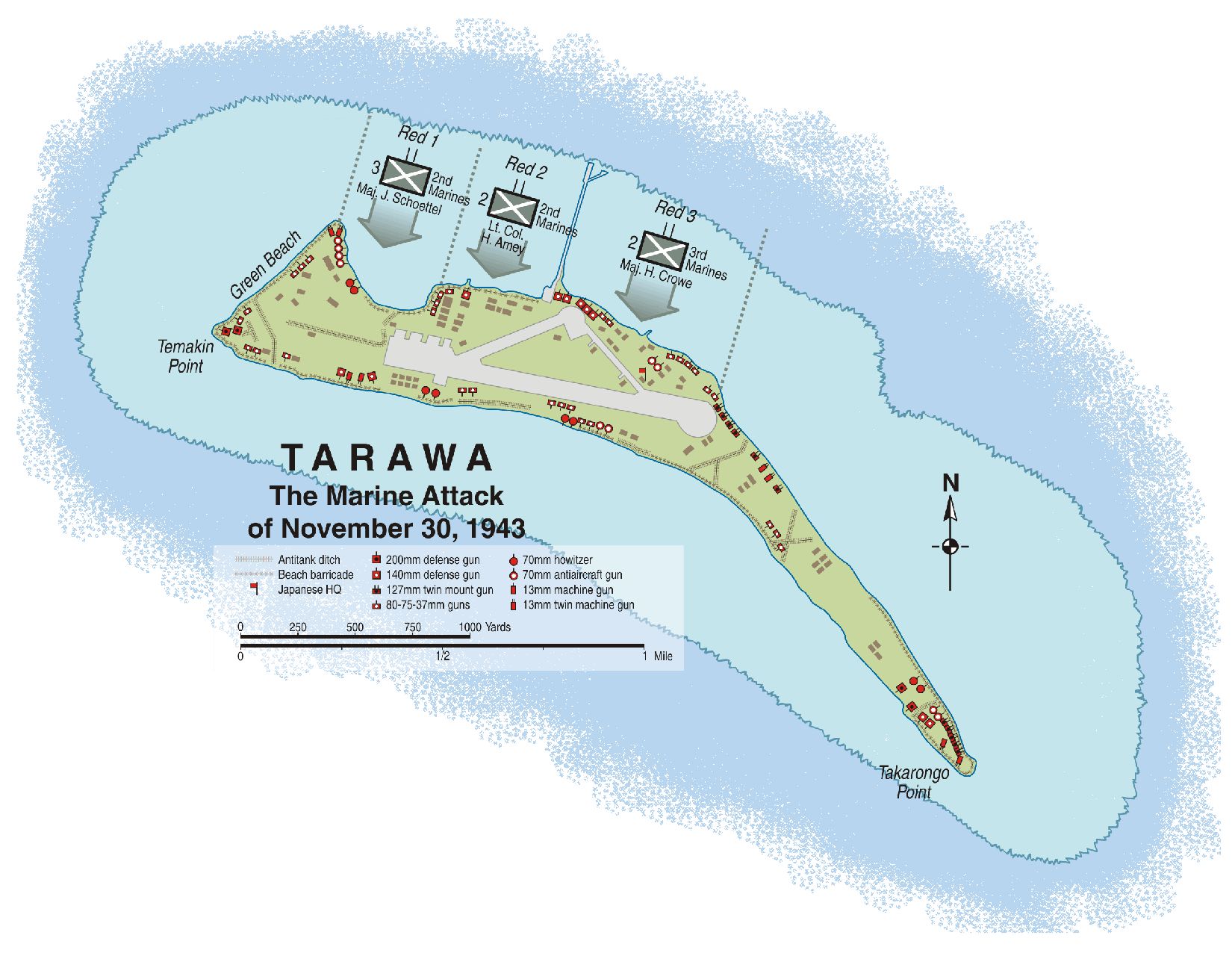

The planners of Operation Galvanic, as the Tarawa invasion was code-named, had established four landing beaches: “Red Beach,” along Betio’s northern shore, was divided into three sectors, from left to right, “Red Beach 1,” “Red Beach 2,” and “Red Beach 3” would be hit on D-Day. On D+1, November 21, the 1,000-yeard beach facing northwest, called “Green Beach,” was scheduled to be assaulted by the rest of the division if a follow-up landing was necessary. On the south shore of Betio were two additional beaches, named Black Beach 1 and Black Beach 2.

The units selected for the Red Beach assaults were 2nd, 8th, and 18th Marine Regiments of the 17,000-man 2nd Marine Division. The division had its baptism of fire during the Guadalcanal-Solomons Islands campaign, and the surviving veterans, many of them still suffering the effects of malaria contracted on “the Canal,” knew what battle was like.

To “soften up” the target, Navy dive bombers, torpedo planes, and fighters, along with B-24 Liberator bombers of the U.S. Seventh Air Force, pummeled Betio for a week before the invasion.

General Smith sent a “pep-talk” message to the Marines who were keyed up and ready for the invasion to begin: “We are the first American troops to attack a defended atoll. What we do here will set a standard for all future operations in the Central Pacific area…. Your success will add new laurels to the glories of our Corps.”

More than one Marine probably shared the thoughts of a grizzled sergeant, wracked with malarial chills and a fever, who had survived Guadalcanal: “To hell with laurels and glory; I just wanted to make it through in one piece.”

Other Marines, who had not yet tasted battle, no doubt imagined that, instead of hordes of Japanese soldiers, throngs of sarong-clad women would be waiting on the beach to greet them with hugs and kisses.

By 4:30 a.m. on Saturday, Novembr 20, the Marines in the first wave had loaded from their transports and were in their amtracs and LCVPs, heading southward toward the lagoon and Betio. The landings, which were supposed to have been carried out in the pre-dawn dark, were suddenly illuminated 10 minutes later by a red star shell fired from shore. The Japanese, who had supposedly all been destroyed, were still alive and ready to receive the invaders.

Shore batteries then opened up on the American ships, hitting some vessels and narrowly missing the Maryland. The battlewagon fired back with 10 salvos from her 16- inch guns. The rest of the ships of the fleet joined the chorus with a roar that sounded like the finale of a Wagnerian opera. A salvo from the destroyer Ringgold made a direct hit on an ammunition dump that resulted in a spectacular pyrotechnic display.

The first wave of landing craft was supposed to have hit the beach by 8:30 a.m. but, because of various delays, it did not happen until 9:10.

The battleships and cruisers opened up, but ceased firing after only 35 minutes in anticipation that the carrier-based planes were about to begin their bombing runs. But the carrier planes were a half hour late, allowing an interval for the defenders to recover from the first shelling. This gap in time, when nothing was hitting Betio, permitted the Japanese to begin firing at the approaching Marine-filled transports.

When the carrier planes finally arrived, they bombed for only seven minutes instead of the planned 30. A scheduled B-24 strike, for unknown reasons, did not take place at all.

When the last plane flew off, the fleet resumed shelling—a battering that lasted for two-and-a-half hours. All told, the Tarawa Atoll had been subjected to a bombardment of six million pounds of explosives.

One Marine recalled thinking during the run-in, “There were fires up and down the length of the island. The feeling was good.” Another remarked, “It’s a wonder the whole goddam island doesn’t fall apart and sink.”

Perhaps because they thought the landing would be “easy,” Marine leadership allowed a greater-than-normal number of war correspondents—both military and civilian—to go in with the assault waves. Army Sergeant John Bushemi, a correspondent and photographer for Yank magazine, wrote, “The Marines were to hit the sandy beach immediately after these softening-up operations ceased, and everybody in the boats was happy because it seemed like very effective fire, the kind of intense blasting that would make the Japs ‘bomb happy.’ But that wasn’t the way it worked out.”

The first group of Marines to reach Betio was 2nd Lt.William “Hawk” Hawkins’ Scout-Sniper Platoon of Landing Team Two. Their mission was to wipe out any enemy troops who might be in possession of a 500-yard-long pier jutting out between Red Beaches 2 and 3. Hawk’s men were initially successful and pushed on toward shore, crawling over the seawall, but the Japanese infiltrated back onto the pier as the day wore on. For two days the pier would repeatedly change hands.

Hawkins continued to expose himself to enemy fire, which resulted in him being hit by shrapnel. Refusing medical attention, he continued to lead his men as they cleaned out Japanese emplacements. But he had not yet accomplished his mission.

After Hawkins and his men had fought their way onto Betio, the next group of amtracs and LCVPs approached the lagoon shore at about 9:10 a.m. Now at low tide, many of the landing craft ran aground a quarter mile or more from the beach.

A machine gunner on an LVT, Marine Private Newman Baird, recalled later, “Bullets pinged off that tractor like hailstones off a tin roof…. We were 100 yards in now and the enemy fire was awful damn intense and getting worse. They were knocking boats out right and left. A tractor’d get hit, stop, and burst into flames, with men jumping out like torches.” About 30 yards from shore, he looked over at the driver, only to see him slumped down, dead.

Baird’s loader was shot. “He was crumpled up beside me, with his head forward, and in the back of it was a hole I could put my fist in.” Baird and three men out of 25 in his amtrac made it to the seawall.

“Those few hundred yards seemed like a million miles,” wrote John Bushemi. “But the Marines kept coming on, across the corpses of other Marines whose lifeless heads were bobbing in the water.”

Historian William B. Hopkins noted, “When LVTs approached the reef, matters changed quickly—for the worse. Many LVTs came to a complete stop. Marines had to leap over the sides into the water and began wading, their weapons held high. Other LVTs managed to go on, though incredibly slowly. It did not take long to realize the worst possible scenario had become a reality: numerous Marines would die as they struggled to get ashore.

“Higgins boats had no chance of crossing the reef because of the low tide. Shibasaki’s garrison survived the … naval and air gunfire in large numbers. Attacking Marines were shocked to find that the naval bombardment had eliminated so few defenders.

The Japanese destroyed the incoming amtracs with such regularity, it is difficult to see how any Marines survived to reach the protection of the seawall.”

In one Higgins boat, Lt. Col. Herbert Amey, commanding Landing Team 2 heading for the log seawall at Red Beach 2, had earlier told his men, “We are very fortunate. This is the first time a landing has been made by American troops against a well-defended beach, the first time over a coral reef, the first time against any force to speak of, and the first time the Japs have had the hell kicked out of them in a hurry.”

Amey was killed during the wade-in; his place was taken by Lt. Col. Walter Jordan. It was a slaughter. The 42 amtracs in the first wave turned into sitting ducks when their fuel tanks exploded or fell into shell holes or had their tracks blown off by artillery. Some went wildly out of control when their drivers were killed, spinning in circles like toy boats and smashing into other landing craft.

At one point, a frightened amtrac driver refused to go in any farther and ordered the Marines onboard to jump ship. They did, but were so overloaded with gear that many of them sank beneath the waves and drowned.

M5 Stuart light tanks crawled out of the surf on Red Beach 3, took enemy positions under fire, and themselves fell victim to heavy fire, land mines, shell holes, and, in one case, the attention of a U.S. Navy dive-bomber.

Enemy fire was relentless—and accurate. Wrote author Raphael Steinberg, “The Japanese began firing while the three lines of amtracs were 3,000 yards from shore. At 2,000 yards, Japanese long-range machine guns opened up. At 800 yards, the drivers of the amtracs started their treads going and the vehicles waddled up onto the reef fringing the island’s lagoon side—only to meet a barrage from every gun in range.”

By the time the battle was over, only about 20 of the original 125 amtracs were still operable.

United Press International correspondent Richard W. Johnston recorded his impressions: “The inside of the lagoon was like a smoldering volcano. The long, flat island was canopied in smoke, its splintered palms looking like the broken teeth of a comb. At many points orange fire studded the haze and at dead center a great spiral of black smoke curled up from a pulsing blaze that now was red, but at first had been white and hot as a magnesium flare. An ammunition dump.”

A desperate message from one of the few working radios reached the fleet: “Have landed. Unusually heavy opposition. Casualties 70 percent. Can’t hold!” Small Japanese tanks rolled toward the line of invaders and were met by American tanks and 37mm anti-tank guns that had been delivered to the shore.

In spite of the rising carnage, Marines continued to brave the fire and make their way to shore. A civilian reporter noted, “In those hellish hours, the heroism of the Marines, officers and enlisted men alike, was beyond belief. Time after time, they unflinchingly charged Japanese positions, ignoring the deadly fire and refusing to halt until wounded beyond human ability to carry on.”

Richard Johnston wrote, “On the sand plateau above the [seawall], the Japs had erected defenses unlike anything the Marines had ever seen. There were big blockhouses and small pillboxes and worst of all, row on row of protected machinegun nests, staggered in support of each other, made into tiny fortresses by sandbags and concrete and coconut logs— fortresses which withstood rifle fire and grenades, and had to be reduced by explosives and flamethrowers.”

In spite of the enemy’s best efforts, the subsequent waves of Marines came on, delivered to Betio by amtracs that plowed their way through floating islands of dead Marines. The still-living Marines jumped into the warm, milky white water made opaque by the constant shelling that had turned the undersea coral into powder, their rifles held high over their heads to keep them dry, the shoreline looking a million miles away. Everywhere continuous white geysers shot up as Japanese bullets smacked the water or found their marks and sent a Marine to his death.

The fifth wave, made up of LCMs (Landing Craft, Mechanized), disgorged their cargo of more a dozen M4 Sherman tanks, which went to work trying to neutralize enemy strongholds. Tragically, many wounded Marines, lying tightly packed together on the coral sand, were crushed when the tanks rolled over them. By day’s end, only two of the 14 Shermans that had made it ashore were still operational.

The observation plane from the Maryland flew over the bloody landscape in hopes of pinpointing targets for the battlewagon’s guns. The pilot later wrote, “The water seemed never clear of tiny men, their rifles held over their heads, slowly wading beachward. I wanted to cry.”

Carl Jonas, a Coastguardsman, recalled the aerial and naval bombardment: “It happened almost immediately. A holocaust dropped from the sky, our fighter planes strafing and searing … the Japanese. From far to the right came the deep, whooming blast of naval gunfire, and the whole Jap side of the island seemed to rise in splinters and flame.”

Incredible stories of heroism came out of the first few hours of the assault. In one open-top amtrac was Marine Corporal John Joseph Spillane, a Major League Baseball prospect. When the amtrac that he and 20 others were in came close to shore, Japanese defenders began lobbing grenades into the craft; Spillane scooped up five like an infielder and tossed them back as his comrades bailed out over the sides. A sixth grenade, however, exploded in his right hand; a surgeon later had to amputate it.

Yank correspondent John Bushemi noted, “The Japs were too well dug in. Their blockhouses were of concrete five feet thick, with palm tree trunks 18 inches in diameter superimposed on the concrete.

And superimposed in the trees were angle irons made of railroad steel. On top of these were 10 to12 feet of sand and coral rock. Only a direct hit by a 2,000-pound bomb would cave in or destroy such blockhouses.”

The Height of the Battle

At about 10:30 a.m., the amtrac carrying Colonel David Shoup and a group of Marines was hit by Japanese fire and everyone jumped out and headed for the long pier separating Red Beaches 2 and 3. Seeing that the men behind him were hesitant to leave the minimal shelter of the pier, Shoup yelled above the noise, “Are there any of you cowardly sons of bitches got the guts to follow a colonel of the Marines?”

While Shoup was trying to run the final 100 yards to the beach, a shell screamed in and knocked the him down, with splinters ripping into his knee. Another shell exploded, killing two men near him, but he continued his advance inland, establishing his command post near a captured bunker at about noon. By now, there were some 1,500 Marines hunkered down on shore wherever the slightest bit of defilade offered protection. Correspondent Richard Johnston noted, “It has been my privilege to see the Marines, from privates to colonels, every man a hero, go up against Japanese fire with complete disregard for their lives.”

One of those colonel-heroes was David Shoup. His Medal of Honor citation reads, “Colonel Shoup fearlessly exposed himself to the terrific and relentless artillery, machinegun, and rifle fire from hostile shore emplacements…. Upon arrival on shore, he assumed command of all landed troops and, working without rest under constant, withering enemy fire during the next two days, conducted smashing attacks against unbelievably strong and fanatically defended Japanese positions despite innumerable obstacles and heavy casualties.

“By his brilliant leadership, daring tactics, and selfless devotion to duty, Colonel Shoup was largely responsible for the final decisive defeat of the enemy.” (Shoup would go on to serve as the 22nd commandant of the Marine Corps.)

The courage displayed by Marines at Tarawa resulted in four Medals of Honor. Besides Shoup’s, another went to Staff Sgt. William J. Bordelon, a member of an assault engineer platoon of the 1st Battalion, 18th Marines. On D-day, most of the men in his amtrac were killed but Bordelon scrambled ashore, assembled demolition charges, and put two pillboxes out of action. While assaulting a third position, he was hit by enemy machinegun fire just as a charge exploded in his hand, seriously wounding him. Waving off medical attention, Bordelon remained in action and, although out of explosives, grabbed a rifle and laid down covering fire while other Marines scaled the seawall.

Disregarding his own wounds, he unhesitatingly went to the aid of one of his demolition men, wounded and calling for help in the water, rescuing this man and another who had been hit by enemy fire while attempting to make the rescue.

Still refusing first aid for himself, he again made up more demolition charges and singlehandedly assaulted a fourth Japanese machine-gun position before he was instantly killed by a burst of fire from the enemy.

By early afternoon on the first day, the 2nd Marine Division had committed all its forces, save for one battalion—the 1st Battalion of the 8th Marines. It would not be nearly enough to overcome the opposition that seemed unfazed by the day’s bombardments and invasion.

Maj. Gen. Julian Smith had only one ace left up his sleeve. Following an urgent request from Shoup, he radioed Maj. Gen. Holland “Howlin’ Mad” Smith, commander of V Amphibious Corps, to see if the 6th Marine Regiment could be released from Corps reserve at Makin Island, 105 miles away, and sent to help the rest of the 2nd Marine Division at Tarawa; Holland Smith said yes; the 6th Marines were no longer needed in the battle for Makin Island.

With the assurance that Colonel Maurice Holmes’s 6th Marines would soon be on their way to Betio (the 6th Marines would not arrive at Betio until D+1), Julian Smith ordered the one remaining 2nd Marine Division battalion that had not been committed to the fight to land at Green Beach. But, due to a failure of communications, the battalion never received the message. (The 6th did eventually come ashore and was immediately thrust into the action, helping to stop a counterattack on the night of November 21-22.)

Communications were a nightmare. After being exposed to seawater, radio sets and batteries quit working; other sets were knocked out by shot and shell. Consequently, units on shore could not talk with one another, and communication between ship and shore was virtually non-existent. Orders for this unit and that unit to move forward, fall back, or move to a lateral position were never received. Commanders had little or no idea what units were where or how the battle was progressing.

Unusual acts of courage were performed by unlikely men. Navy Lieutenant Solomon Kozol was a dentist with the 8th Marines.

He had volunteered to go in with the initial waves in case anyone needed facial wounds to be treated. He carried wounded men through the churned-up surf to the landing craft and returned with five-gallon cans of water. He was hit in the arm by a bullet during one of these missions; he was awarded both the Purple Heart and Silver Star.

Another officer who spent much of his day rescuing wounded was Marines Lt. (jg) Edward Heimberger, better known to Hollywood movie audiences as the actor Eddie Albert. Aboard a Higgins boat that was ferrying supplies to the island, he repeatedly braved enemy fire to pull injured men into his craft and evacuate them to the transports lying offshore.

As D-day raged on and turned into evening, the Americans were clinging tenaciously to their positions on Betio. The Marines, or what was left of them, held the narrow strip of Red Beaches 1, 2, and 3, and had pushed inland from 70 to 150 yards at various places.

Ammo and drinking water and medical supplies were running dangerously low, and there was no food. Wounded and dying Marines moaned softly. As soon as it got dark, the Marines were sure waves of enemy soldiers would rush at them in their banzai charges. But no counterattacks, save for one nuisance raid by a single Japanese plane, materialized.

The Second Day

At dawn on D+1, with Sherman and Stuart tanks and 75mm artillery pieces arriving, carrier-based Hellcats roared in to plaster Japanese positions while the big guns of the Navy added their voices to the overall din. More Leathernecks arrived as the sky lightened. At 6:15 a.m., the 1st Battalion, 8th Marines, led by Major L.C. Hays, Jr., waded in toward Red Beach 2 from their boats (they had been waiting offshore for 20 hours) but were cut to pieces by Japanese who had, during the night, swum out to the disabled amtracs and Higgins boats lying offshore and used the abandoned machine guns.

Fire also came from a disabled Japanese freighter that lay like a dead whale just off the beach. Shoup ordered the Marines to silence both sources of this unexpected fire, and they did.

Robert Sherrod saw Hays’s men fall in droves: “Within a few minutes I count at least 100 Marines lying on the flats…. There are at least 200 bodies which do not move at all on the dry flats, or in the shallow water partially covering them. This is worse, far worse than it was yesterday.” Out of 800 men, the battalion lost 331 men killed or wounded. But those who made it gave Shoup the weight he needed to begin overcoming the defenses.

On Red Beach 1, arriving reinforcements were met with such an intense volume of Japanese fire that the Marines were forced to retreat back to the shelter of their landing craft.

A lieutenant colonel who earlier had been displeased with the reinforcements who had held back now praised them: “Once we got these men off the beaches and up front, they were good,” he said. “They waded into the Japs and proved they could fight just as well as anybody.”

Finally, a rising tide enabled the Higgins boats to release their human cargo closer to shore—and relative safety.

Lieutenant William “Hawk” Hawkins, still leading the Scout-Sniper Platoon despite the wounds he had suffered the first day, was hit a second time but again shrugged it off. He was at the head of his men attacking three more pillboxes when shrapnel from a Japanese shell ripped into him, killing him. For his heroic leadership and selfless sacrifice, he was awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor.

Slowly and cautiously, the Marines, who now numbered about 5,000, continued advancing across the width of island, reaching the airfield, and progressing farther to the south, destroying or bypassing enemy bunkers and pillboxes.

Shibasaki Dead

Early on D+2, Admiral Shibasaki, perhaps knowing that the defense of the atoll was futile, sent a final message to General Headquarters in Tokyo: “Our weapons have been destroyed and from now on everyone is attempting a final charge…. May Japan exist for 10,000 years!”

Shortly thereafter he met his death. Historian Joseph H. Alexander wrote, “[Shibasaki] gave up his concrete blockhouse to be used as a hospital for his hundreds of casualties, assembled his staff in the open, and began to move to a secondary command post several hundred yards away. In one of the ironic flukes of battle, a Marine with perhaps the only working field radio on the island spotted the cluster of officers in the open and quickly called in naval gunfire.”

The shells from two destroyers fell on the group, killing Shibasaki and his entire staff. The defenders were now, for all intents and purposes, leaderless. Without anyone to coordinate the defense of Betio, it was only a matter of time before the island would fall.

But there was still more savage, no-holds-barred fighting that would take place before the Marines could declare Betio secured.

Correspondent Robert Sherrod noted that the tide had receded during the night, leaving dead and wounded Marines lying exposed on the sand: “Further out on the flats and to the left I can see at least 50 other bodies. I had thought yesterday, however, that the low tide would reveal many more than that. The smell of death, that sickly sweet odor of decaying human flesh, is already oppressive.”

Another correspondent, Robert Johnson, noted, “The smell was inescapable. It was everywhere…. It suffused the Marines’ hair, their clothing, and seemed to adhere to their bodies.”

The battle for Betio was reaching a crescendo, with scenes of horror unlike any seen before. Carrier-based planes swooped in to strafe and drop ordnance on Japanese positions (and, sometimes accidentally, on Marine positions as well), and tanks rumbled forward to blast the pillboxes with their main guns. Marines risked death to toss grenades, blocks of TNT, and satchel chargers into the firing slits of bunkers.

Artillery pieces on both sides barked and land mines exploded. Machine guns kept up a steady rattle while flamethrowers burned stubborn defenders out of their emplacements.

A number of enemy snipers tied themselves high up in the fronds of battered, forlorn palm trees, and killed many Marines before they themselves died. In their surrounded bunkers, many of Dai Nippon’s finest elite soldiers chose to commit suicide rather than surrender.

The dwindling number of Japanese soldiers seemed more determined than ever to prevent the main prize—the airstrip—from falling into American hands, and some of the toughest fighting took place around its perimeter. But the Marines would not be stopped, and many of them made it across the airfield all the way to the island’s southern coast. With the tide of battle beginning to turn, Maj. Gen. Julian Smith sent in his just-arrived reserves—the 6th Marine Regiment.

At 5 p.m. on D+1, bloodied and bone-tired David Shoup radioed to Smith: “Casualties many, percentage dead not known. Combat efficiency: We are winning.” The wounded and exhausted Shoup was relieved by Smith’s chief of staff, Colonel Edson, who took overall command of Marine forces on land and in the lagoon.

John Bushemi wrote, “After the second day, the [Marines] were able to penetrate to the opposite shore of Betio … and by this time the critical period was past. But the fighting was not ‘officially’ over until 76 hours had passed from the time of the assault, and even then there was still a handful of Jap snipers in trees and dugouts that had to be picked off.”

The Third Day

On the third day of battle, bleary-eyed Marines crawled out of their foxholes and bomb craters and advanced grimly forward, attacking every bunker and pillbox and killing every enemy soldier they could find.

Another posthumous Medal of Honor went to 33-year-old 1st. Lt. Alexander “Sandy” Bonnyman Jr., executive officer of for his actions on D+2. His citation reads, in part, “Acting on his own initiative when assault troops were pinned down at the far end of Betio Pier by the overwhelming fire of Japanese shore batteries, 1st Lt. Bonnyman repeatedly defied the blasting fury of the enemy bombardment to organize and lead the besieged men over the long, open pier to the beach and then, voluntarily obtaining flamethrowers and demolitions, organized his pioneer shore party into assault demolitionists and directed the blowing of several hostile installations.”

Bonnyman then led his demolition party to neutralize a giant blockhouse near the end of the pier that was pinning the Marines down. His troops managed to set their charges, killing about 150 enemy soldiers inside and cutting down another 100 who tried to escape.

John Wukovits wrote, “As he braved fire from the defenders, Bonnyman waved his engineers toward the top, where some quickly eliminated the machine guns posted on the crest while others ran over to the air vents…. Bonnyman kept encouraging men, despite the bullets that whizzed through the air and smacked into the sand.

“Finally, Bonnyman’s luck ran out. As he rose on one elbow to tell someone to bring more charges, a bullet instantly killed the lieutenant.”

Like so many other Marines, Bonnyman’s remains were buried a mass grave along with hundreds of others, then later removed to the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Hawaii to a grave marked “Unknown.”

In truth, many more Medals of Honor could have been handed at Tarawa. That night, a banzai charge by the few remaining defenders was nothing more than mass suicide. Dawn the next day revealed mounds of Japanese soldiers intertwined in death.

By sheer attrition, the tenacious Japanese who refused to surrender were ground down until, at last, there were no more of them left to resist the Marines. The Seabees (Construction Battalions) came ashore with their heavy equipment to fill craters in the airstrip, take out pockets of resistance, destroy stout bunkers, and bury some enemy positions under tons of sand and rock. They also later scooped out mass graves into which dead Marines and the Japanese were buried—separately.

Correspondent Jim Lucas wrote, “The stench of death hung over Betio. We had slaughtered more than 4,000 Japanese. Their grotesquely burned, blackened corpses littered every foot of the atoll, many of them dead for three days. They were bloated and swollen. For weeks we were to taste and smell corruption.”

William Manchester, the author and World War II Marine, wrote in Goodbye, Darkness, “At the time it was impolitic to pay the slightest tribute to the enemy, and Nip determination, their refusal to say die, was commonly attributed to ‘fanaticism.’

In retrospect it is indistinguishable from heroism. To call it anything less cheapens the victory, for American valor was necessary to defeat it.”

The island was steeped in carnage. “Betio would be more habitable if the Marines could leave for a few days and send a million buzzards in,” Sherrod wrote later.

Although the Marines would suffer more casualties in early 1945 at Iwo Jima, Colonel Edson said the assault force “paid the stiffest price in human life per square yard” at Tarawa than any other battle in Marine Corps history.

Maj. Gen. Julian Smith toured the battlefield November 24 and was both appalled and heartened by the scenes of carnage. “I saw Marine dead in rows along the beach,” he said, “and couldn’t help noticing that every man had fallen face forward, some within a few feet of the Jap guns they were trying to take.”

On that same day, what was left of the battered 2nd Marine Division departed Tarawa for a period of rest and recuperation in Hawaii—and to prepare for their next assignment: Operation Forager, the invasion of the Mariana Islands. After their departure, the Seabees began work to improve the island’s airstrip—which was named Hawkins Field in honor of 1st Lt. William Deane Hawkins—and turn the island into an American military base.

“In all, an enemy force of about 4,500 defenders was wiped out, including about 3,500 Imperial Marines and 1,000 [Korean] laborers,” Bushemi wrote in Yank. “Fewer than 200 of the defenders surrendered, most of them laborers.

Tarawa was taken by less than a division of U.S. Marines. We suffered the loss of 1,026 men killed and 2,557 wounded. The 2nd Marine Division took this island because its men were willing to die.”

Bushemi, 25, died covering the fighting on Eniwetok Atoll in the Marshall Islands on February 19, 1944.

Maj. Gen. Holland Smith noted after the war, “These Japanese were masters of defensive construction. The Germans never built anything like this in France [on the Atlantic Wall]. No wonder these bastards were sitting back here laughing at us! They never dreamed the Marines could take this island, and they were laughing at what would happen to us when we tried.”

Not everyone was pleased with the costly victory. General Douglas MacArthur, furious that the 2nd Marine Division had been taken from his Southwest Pacific Command, complained to the Secretary of War: “These frontal attacks by the Navy, as at Tarawa, are a tragic and unnecessary massacre of American lives.” Although eclipsed by other battles (such as Iwo Jima), the battle for Tarawa has been called “the toughest battle in Marine Corps history.” Admiral Nimitz added, “The capture of Tarawa knocked down the front door to the Japanese defenses in the Central Pacific.” He launched the campaign to take the Marshalls just 10 weeks after the capture of Tarawa.

Time-Life correspondent Robert Sherrod perhaps summed it up best: “It was inconceivable to most Marines that they should let one another down, or that they could be responsible for diminishing the bright reputation of the corps…. The Marines simply assumed they were the world’s best fighting men.”

Tarawa proved it.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments