By Pedro Garcia

One evening around Christmas of 1861 Union Maj. Gen. Henry “Old Brains” Halleck, commanding the Department of Missouri, dined with his chief of staff, Brig. Gen. George Cullum, and an old Mexican War friend, Brig. Gen. William T. Sherman. Halleck, standing over a map on his table with a large pencil in his hand, asked, “Where is the Rebel line?”

Cullum drew a line through three points: Bowling Green in south central Kentucky; Columbus, a Kentucky town on the Mississippi River; and Forts Henry and Donelson in between the two towns just south of the Tennessee border.

“That is their line,” said Halleck. “Now where is the proper place to break it?” Either Cullum or Sherman responded, “Naturally, the center.”

Then Halleck drew a line perpendicular to the first near its middle, the pencil stroke following the general course of the Tennessee River. He said, “That’s the true line of operations.” Halleck had marked the great geographical axis by which the lower South could be pierced.

The Drunkards Grant and Foote

Seen from the Atlantic coast, the task of Northern armies appeared (at least to a skeptic) almost impossible, for the South looked truly boundless, an ocean of fields, valleys, mountains, forests, and rivers. But rivers could be daggers as well as obstacles. They cut deeply into the Confederacy’s heartland. Indeed, no geography was ever more favorable to a modern invading army than Kentucky’s was to the Union Army in early 1862. What made it so were the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers. The Tennessee, navigable all the way from its mouth at the Ohio River to the Muscle Shoals at Decatur, Ala., and the Cumberland, navigable from its mouth at the Ohio River to Nashville, Tenn., and beyond, pierced the Confederate east-west defensive line that Cullum had marked. They pierced it, in fact, not more than 20 miles apart. It was along this geographical axis that Generals Halleck and Ulysses S. Grant and Flag Officer Andrew Foote ruptured the defenses of Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston.

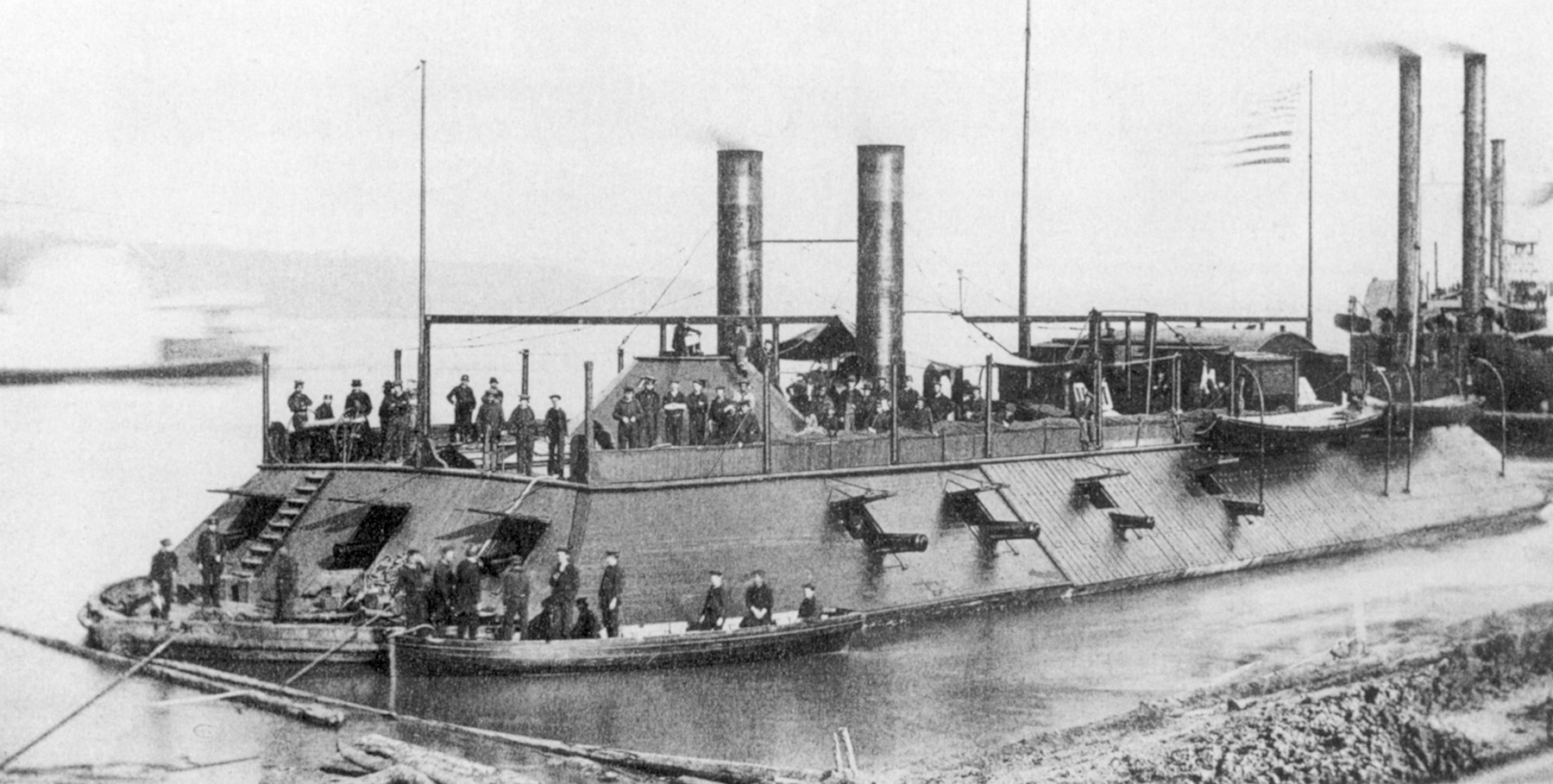

At the end of the summer of 1861, Southerners realized that the most immediate and potentially deadly threat to the Confederacy would not come from the east, but from the west, where the Union was unexpectedly seizing the initiative. In mid-August, the Missouri engineer and entrepreneur James Eads, a man of boundless energy, talent, and ability, was given a contract to build seven ironclad gunboats in 64 days. A true mechanical and organizational genius, the Indiana native was included in the Southern sneer at the North as “a race of pasty-faced mechanics.” Working at drumbeat speed, by the end of November he was able to launch eight “turtle-backed” steamers. These vessels made a formidable squadron totaling 5,000 tons, mounting 107 guns, and with an average cruising speed of 9 knots. The 175-foot river craft drew only 51/2 feet of water, and, in river parlance, “could run on a heavy dew.”

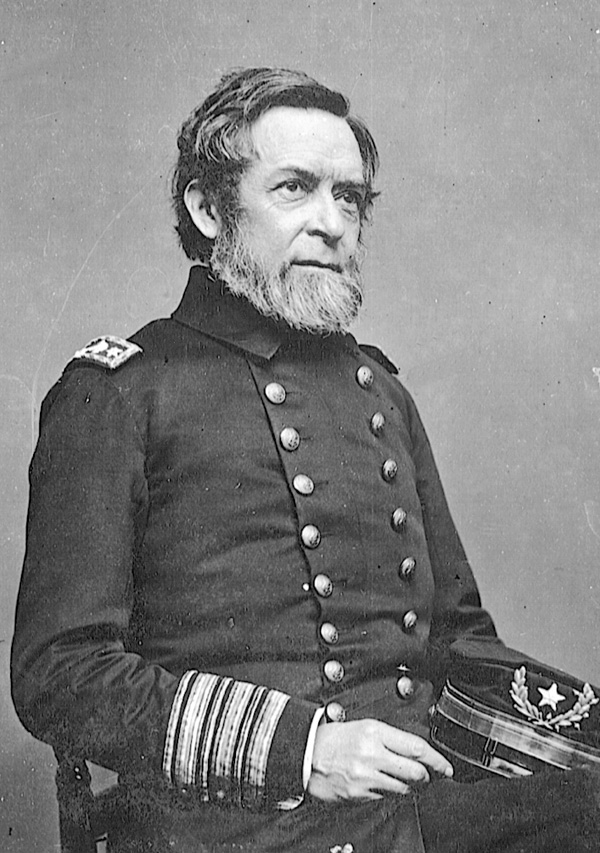

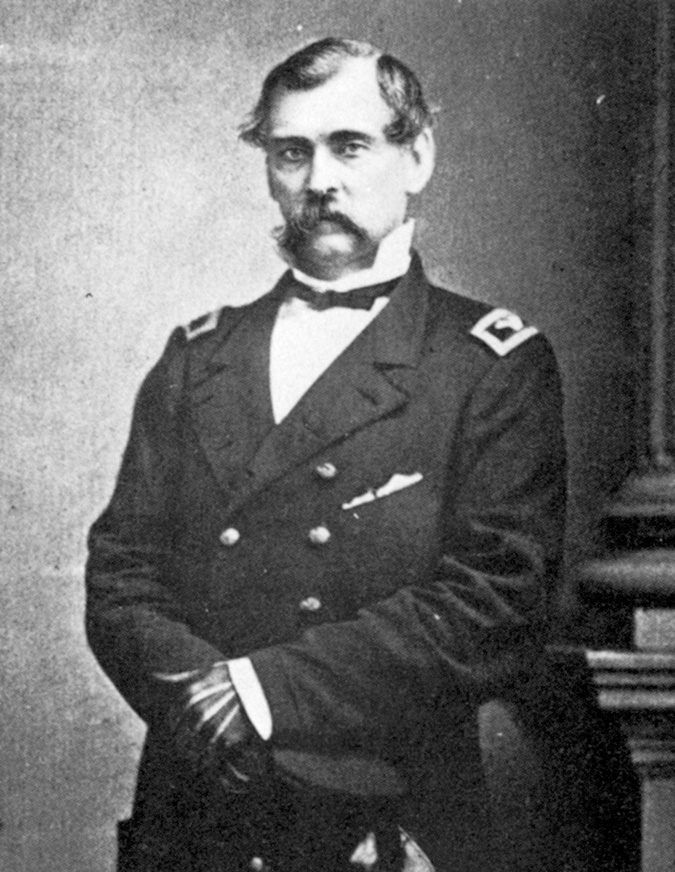

To command this flotilla, the U.S. Navy commissioned Captain Andrew Foote with the rank of flag officer. A staunch Calvinist, Foote was a 56-year-old, teetotaling Connecticut Yankee with burning eyes. A man who spoke sparingly, he was one of those Puritans who “prayed like saints and fought like devils.” A 40-year veteran, Foote had fought the Chinese in Canton, battled pirates in Sumatra, chased slave traders in the South Atlantic, and 20 years before had commanded the first temperance ship in the U.S. Navy. Indeed, he had spent his entire career fighting the two things he hated most: slavery and whisky.

Odd then was the fate that teamed Foote in the coming campaign with Ulysses S. Grant, a man who had a reputation as a drunkard and a drifter in the prewar Army. In 1854, Grant had resigned his captain’s commission because of his drinking problems and had fared poorly in civilian life. When war came, however, Grant had impressed enough people that he received an appointment as colonel of Illinois volunteers, and soon was promoted to brigadier general, proving himself an excellent executive officer. Grant was an unobtrusive, mild-mannered, colorless officer, a recent biographer admitting that “there is almost no glamour in the figure.” Yet Grant was a relentless warrior and an extraordinary general whose approach to war was uncomplicated. He later wrote that “the art of war is simple enough, find out where your enemy is, get at him as soon as you can, strike him as hard as you can, and keep moving on.” Both Grant and Foote believed strongly in combined operations, trying to convince Halleck that the Army and Navy “were like blades of a shears—united, invincible, [but] divided, almost useless.”

Albert Sidney Johnston: “A Real General”

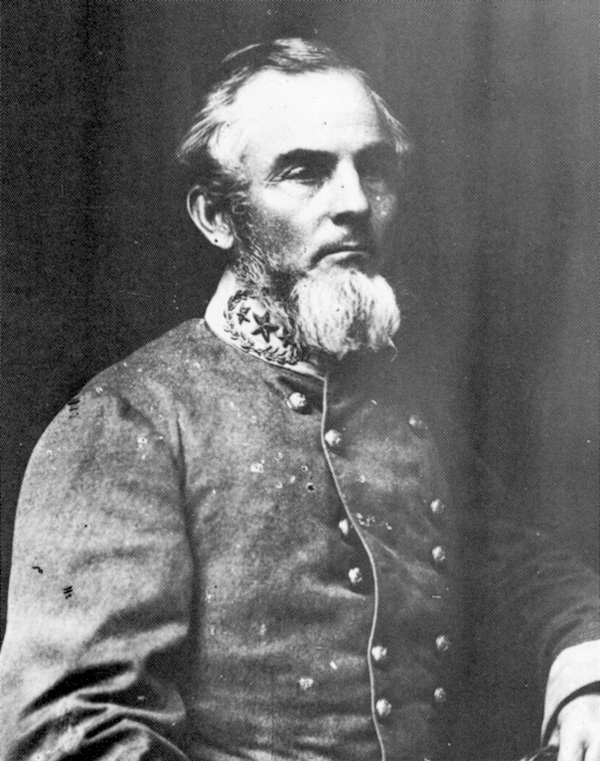

Albert Sidney Johnston was painfully aware of the weakness of his position. Commanding the Confederacy’s vast Department No. 2, he was expected to hold a line nearly 600 miles long and broken by three navigable rivers. He had few troops and even fewer arms. “The General lacked nothing except men, munitions of war and the means of obtaining them,” his son later wrote in a bitter reminiscence. A 58-year-old, Kentucky-born Texan, he had distinguished himself in a colorful career: frontier officer, Texas revolutionist, Secretary of War in Sam Houston’s cabinet, Mexican War colonel, and commander of the famed 2nd Cavalry, whose roster included the names of 10 future generals. Grant “expected him to be the most formidable the Confederacy would produce,” and William Sherman pronounced him “a real general.”

This counted for little, however, when he was outnumbered nearly 2 to 1. In reality, Johnston held no line. What he held was a series of points divided by wide stretches of unoccupied territory. In fact, there was a fourth avenue of invasion available to the Union along the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, which connected with rail lines to Chattanooga and the lower South. The river routes, however, were the most likely approaches because they offered excellent and secure communications. There was no practical limit to the capacity of navigable rivers to supply the Union armies so long as they had enough boats. As Sherman said, “We are much obliged to the Tennessee which has favored us most opportunely … for I am never easy with a railroad which takes a whole army to guard … whereas they can’t stop the Tennessee, and each boat can make its own game.”

Forts Henry and Heiman

The Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers, crossing the critical center of Johnston’s “line,” constituted, as author Shelby Foote aptly put it, “a double barreled shotgun leveled at his heart.” To protect against this threat, the rivers were guarded by hastily built forts. Forts Henry and Heiman stood on opposite banks of the Tennessee River near the Kentucky-Tennessee border. Fort Henry stood on the marshy eastern bank and was built in a tactically vulnerable position, being relatively low in elevation, partially inundated by floodwater, and on a dangerous salient open to enfilading fire.

The smaller Fort Heiman stood on the western shore, unfinished and unarmed, and in such bad shape that when Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman arrived on the scene to take command he ordered Heiman’s men to abandon it in favor of consolidating at Fort Henry. In all, Tilghman counted 3,400 defenders who “were not drilled, badly equipped, and very indifferently armed with shotguns and hunting rifles.” Additionally, poor camp sanitation and sickness had further reduced the garrison by as much as one- fifth, and one company’s only duty was “trying to keep water out of the fort.” In fact, the river had recently risen so quickly that only nine of the 15 guns bearing riverward remained above water. The rising water also negated the effectiveness of some 20 mines, called torpedoes, that had been placed in the river. These sheet-iron cylinders, 5 feet long by 1 foot in diameter, held 70 pounds of black powder and were anchored to the river bottom at normal flow level. A tiprod from the top of each activated a musket lock that fired the weapon when a vessel brushed the rod. As the water rose, these became useless.

Union Gunboats on the Tennessee

Halleck, aware of the frightful condition of the winter roads, planned to use the superior mobility afforded by water transportation. But it was Grant who took the initiative and forced the issue. When Foote advised Grant about the onset of low water, Grant pressed his commander until Halleck committed himself to the action. The campaign began in the rainy, early evening darkness of February 3, when the fleet slipped its moorings and moved southward up the swift-flowing Tennessee toward Forts Henry and Heiman. Leading the way was a squadron of gunboats: five ironclads—USS Essex, Lexington, St. Louis, Carondelet, and Foote’s own flagship, USS Cincinnati—and two timber-clads—Tyler and Conestoga. They escorted nine transports that carried Grant’s Army of West Tennessee, comprising 15,000 men in three divisions commanded by Brig. Gens. John McClernand, Charles Smith, and Lew Wallace. Supporting the infantry were two regiments of cavalry and eight batteries of artillery. Grant’s movement would take place in two columns on either side of the river. He intended to land as close to the forts as possible.

Dawn brought good and ill for the Confederates. The temperature was unseasonably warm for February, which no doubt pleased them, but daylight also revealed the approach of their enemy. “Far as the eye could see, the course of the river could be traced by the dense volumes of smoke issuing from the flotilla—indicating that the long-threatened attempt to break our lines was about to be made in earnest,” recalled Rebel artillery officer Captain Jesse Taylor.

To reconnoiter suitable points along the riverbanks for landing his troops, Grant boarded the ironclad Essex, William D. “Dirty Bill” Porter commanding. The boats steamed to within two miles of the forts, crabbed into line abreast, and opened fire. The guns of Fort Henry barked wildly in protest. They quickly found their range, and a solid shot was put squarely into the Essex. The shell screamed over the spar-deck, narrowly missing Grant and Porter, and slammed into the officer’s quarters. After ripping through the captain’s quarters and steerage, the shell erupted from the stern and dropped hissing into the river. A visibly shaken Grant decided to turn about and have his army disembark four miles downriver. That having been decided, Grant resolved to take command on the east bank, and ordered Smith to command the west bank and capture Fort Heiman. The landing was completed the next day, February 4.

Jesse Taylor recalled it as a day “of unwonted animation on the hitherto quiet waters of the Tennessee … the flood-tide of arriving and departing transports continued ceaselessly.” Then, at sunset, the skies opened up, flooding the already swollen river to new heights.

Withdrawing to Fort Donelson

As the enemy buildup continued, General Tilghman began to comprehend the enormity of the odds he faced, and that night called a council of war. He announced that he could not allow himself to be entrapped in a shipwrecked fort or have his communications cut, and so would withdraw the garrison to Fort Donelson. As Tilghman’s artillery chief observed, “Surrounded by water … cut off from the support of infantry, and on the point of being submerged, our whole force is wholly inadequate to cope with that of the enemy, even if there had been no extraordinary rise in the river.” To discourage pursuit and buy time for the fleeing troops, Tilghman stayed with a skeletal force of about 75 men to work the guns. Only two of these, a high-velocity six-inch rifle, which had already struck the Essex, and a giant 128-pound Columbiad, were capable of damaging the gunboats’ armor.

On the morning of February 6, the Union fleet awoke to a deep mist and found that the storm of the evening before had sent great bulwarks of rushing flotsam, including whole trees torn out by their roots, piling up around the bows of the vessels. Lookouts aboard the Carondelet reported a number of large white objects, “which through the fog looked like polar bears coming down the stream,” recalled Captain Henry Walke. These were the mines that had lolled beneath the surface of the river, torn from their moorings by the swift current.

It was careful work to drag these mines ashore and remove all other impediments, but soon a breeze came up, clearing the fog, and the warships weighed anchor. The squadron of four ironclads and three timberclads steamed up to within 1,700 yards of Fort Henry, “until as they swung into the main channel … they showed one broad and leaping sheet of flame,” observed Taylor. “At once the fort was ablaze with the flame of her heavy guns,” recalled Walke. One defender proudly called the reply “as pretty and simultaneous a broadside as I ever saw flash from the sides of a frigate.”

“The Gunboats Are the Devil.”

The guns also delivered with trip-hammer rapidity and accuracy. As many as 62 hits were scored against the Union flotilla, one against the luckless Essex. After taking the head off the master’s mate, the solid shot smashed into one of Essex’s boilers, spewing forth a ghastly brew of gaseous fires and tons of boiling water. A wall of superheated steam, shooting through the forward end of the casemate, flashed up the hatchway into the pilothouse, instantly killing the helmsman and a gunner.

“The scene was almost indescribable,” remembered James Laning. “The dead man, transformed into a hideous apparition, was still at the wheel, standing erect, his left hand holding the spoke, and his right hand holding the signal bell-rope…. One man was on his knees in the act of taking a shell from the box to be passed to the loader. The escaping steam had struck him square in the face, and he met death in that position.” Badly mauled, and with 38 casualties, the out-of-control Essex drifted downstream.

“The fleet seemed to hesitate,” noticed Taylor. But it was only for a moment. Relentlessly the “turtles” pressed forward, closing the range. Fifteen-second fuses were cut to 10, then five. Gun elevations came down nearly flat, “and every shot went straight home. His shot and shell penetrated our earthworks as readily as a ball from a navy Colt would pierce a pine board,” Taylor recalled. The Confederates put up a valiant fight for about two hours, but when the six-inch rifle burst and the giant Columbiad was accidentally spiked by a broken priming wire, they lost heart. Aware that the long odds were getting longer, and satisfied that he had given the fleeing garrison a two-hour headstart to Fort Donelson, Tilghman struck his colors.

“The river had risen so high,” wrote historian Stanley Horn, “that when Foote’s officer approached to receive the surrender his cutter sailed through the sally port.” Meanwhile, Grant’s army was battling the backwater sloughs, slugging through the muck and mire in the marshy bottoms, arriving one hour later, at 3 pm.

This had been Foote’s fight. He had lost 12 killed or missing and 27 wounded, compared to the fort’s 10 killed or missing and 11 wounded. Drawing on the Nashville Union and American newspaper of February 8, Foote could proudly quote the Southern feeling about the operation:“We had nothing to fear from a land attack, but the gunboats are the devil.”

Johnston Divides His Forces

Suddenly it was a different war. Fort Henry was like the first domino that, in falling, sets in motion the collapse of an entire row. Grant immediately exploited the success by sending Foote’s gunboats upstream to break the Memphis and Ohio Railroad bridge over the river, thus protecting himself by severing a major artery of Rebel communications, supplies, and troops. The gunboats continued 150 miles upstream, knocking out other bridges and cutting telegraph lines, all the way to Muscle Shoals, Ala., where the town of Florence was surrendered. The fact was, with Fort Henry in Union hands, all the Confederates could do was retreat. This was clearly seen by the man who would eventually lead Union armies to victory in the war. Grant wrote his wife that the advance on the Tennessee River gave the Union “such an inside track on the enemy that by following up our success we can go anywhere.”

As the Union commander was preparing to get his army across the 12-mile neck of land from Fort Henry to Fort Donelson, Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston decided on February 11 to abandon Bowling Green, a vital point of his defensive “line” in Kentucky, and concentrate his forces at Nashville, Tenn. He also reasoned that with Fort Henry taken, Fort Donelson would be untenable. Yet inexplicably, after deciding the fort was indefensible, he ordered several thousand troops into it. Thus Johnston divided his army, failing to achieve a concentration.

Advancing on Fort Donelson

Brigadier General John B. Floyd commanded these reinforcements. Floyd was a former governor of Virginia whose ignorance of military affairs had not been remedied by lackluster service as secretary of war in the 1850s, nor by his feckless and inept performance in the fall of 1861 under Robert E. Lee in West Virginia. He had shown a tendency to get flustered under pressure and would again prove indecisive and vacillating. His uninspiring subordinates were Brig. Gen. Gideon Pillow, a pretentious Tennessee lawyer who should have stayed at the bar, and Brig. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner, an old friend and West Point classmate of U.S. Grant who inclined toward being saturnine.

Grant originally expected to take Fort Donelson two days after the fall of Fort Henry, but he found himself slowed, “perfectly locked in by high water and bad roads, and prevented from acting offensively.” As he stood gazing forlornly at the waste of wetness in his path, it began to snow and then violently rain. The roads became “bottomless gumbo,” wrote Grant. The rain “soaked the soft alluvial soil of the bottoms, until under the tread of troops it speedily became reduced to the consistency of soft porridge of almost immeasurable depth, rendering marching very difficult for the infantry, and for the artillery almost impassable.”

Halleck, meanwhile, perceiving a Confederate counterattack because Grant had been delayed, reinforced him with 10,000 troops, as well as picks and shovels. About midmorning of the 12th the weather turned fair and the troops moved out under a hot sun. In the spring-like atmosphere the soldiers began to discard what they felt they could spare. Major James Connolly wrote that “the ground was strewn with … coats, pants, canteens, cartridge boxes, bayonet scabbards, knapsacks … all sorts of things that are found in the army.” By nightfall, most of the Federals were deployed on a high ridge opposite Fort Donelson. “We kept closing in slowly, and at dusk were within pistol shot of their rifle pits,” recalled Lieutenant W.D. Harland of the 18th Illinois. Meanwhile, Grant had urged Foote to bring his gunboats in position on the Cumberland and repeat the bombardment given at Henry.

The Untactful McClernand and the Outstanding Smith

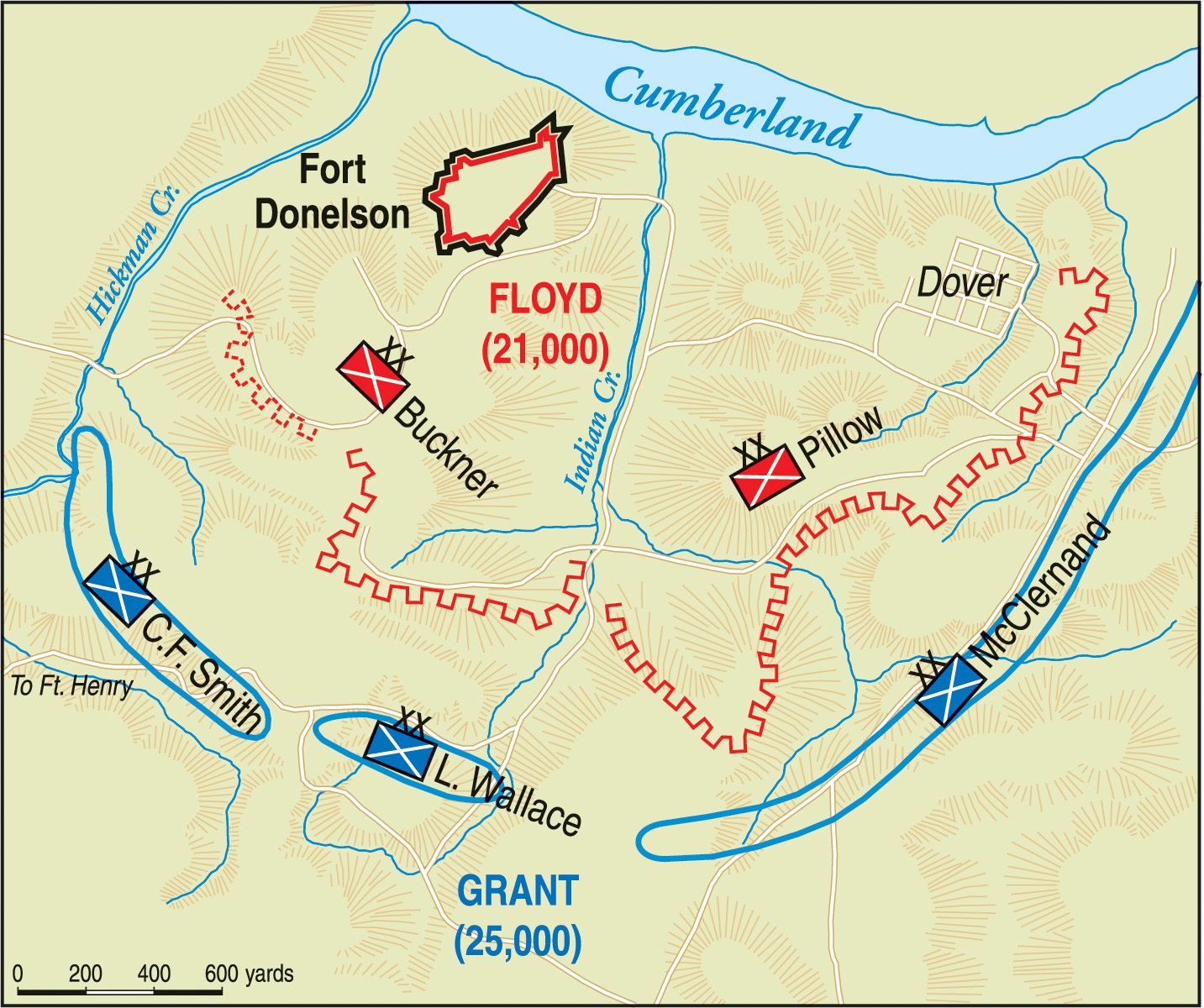

Fort Donelson, encompassing about 20 acres, consisted of a semicircle of earthworks and entrenchments situated on a ridge west of the hamlet of Dover, Tenn. Formidable batteries set high on a bluff guarded the river approach. It enjoyed the advantage of being fronted by deep gullies and flanked by swamps and two flooded creeks—Hickman Creek to the north and Indian Creek to the south. Floyd’s ring of trenches had Pillow’s troops south of the fort and town, and Buckner’s west of it.

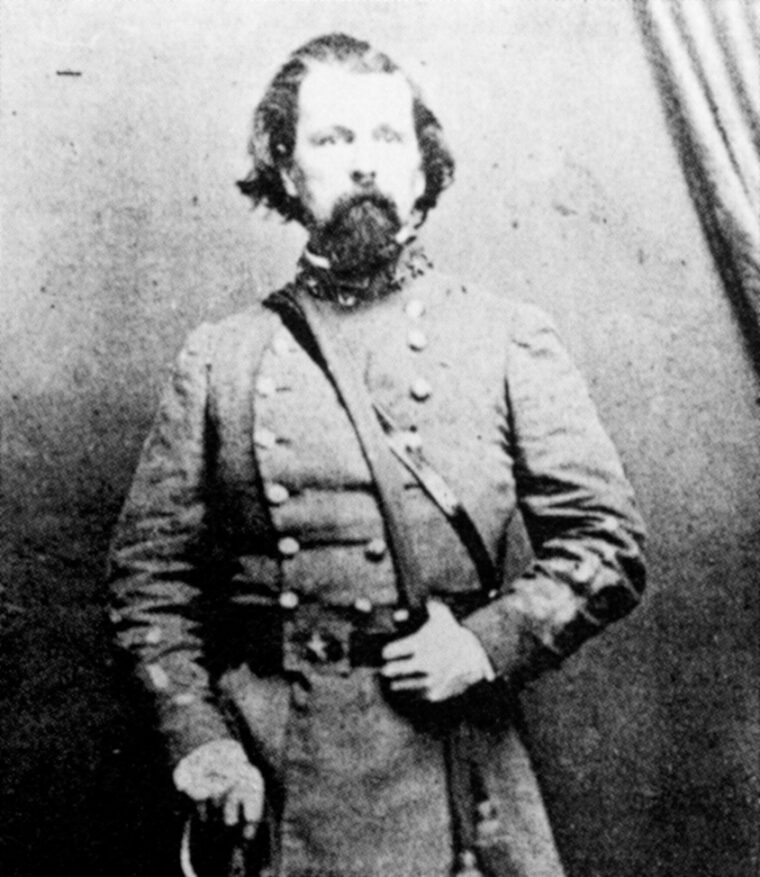

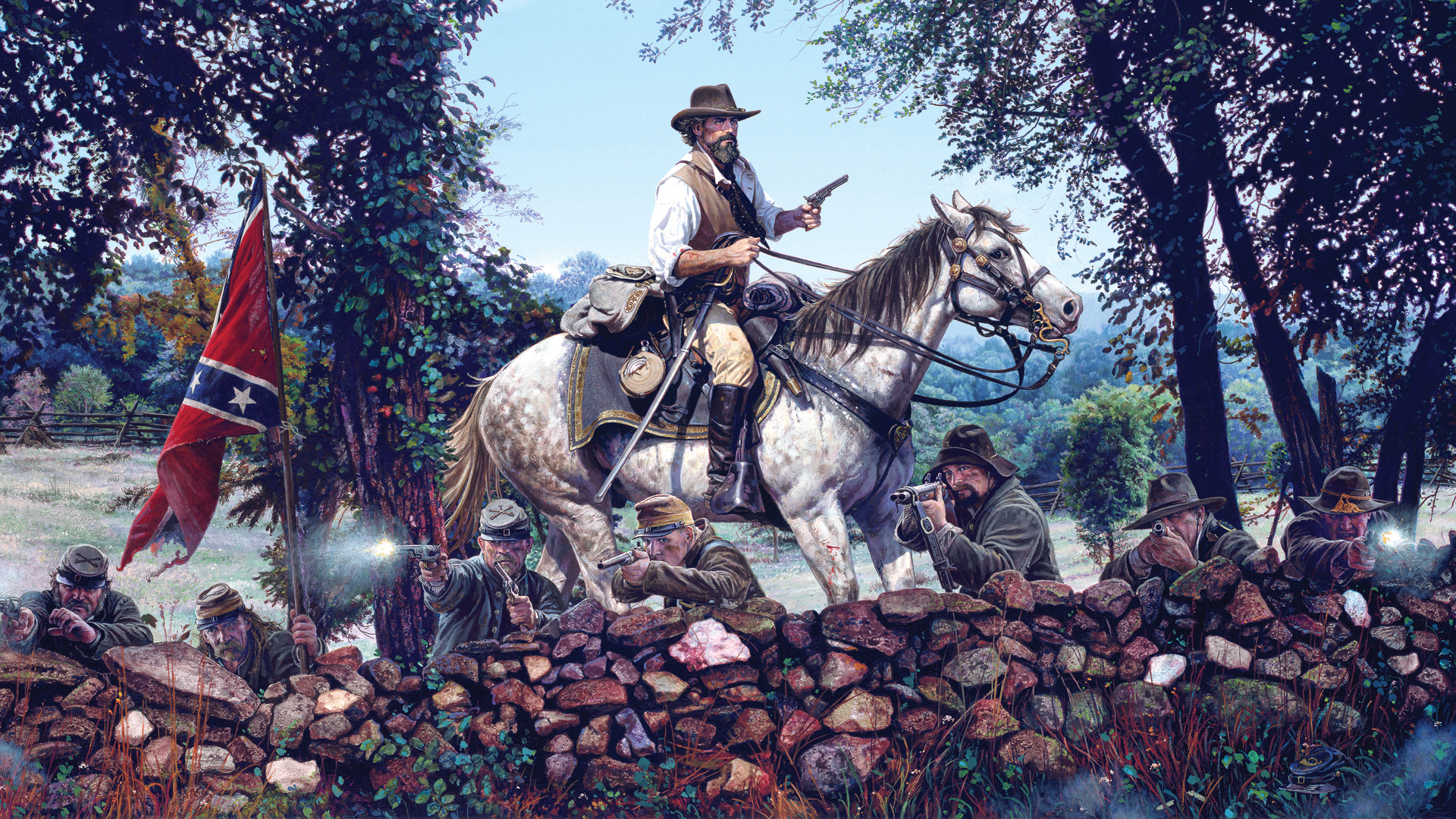

The cavalry was led by Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest, who would become one of war’s more remarkable figures. Tennessee-born Forrest had moved to Mississippi and, despite receiving a scant education, had become a wealthy planter and slave trader.

Floyd commanded 28 regiments, 17,000 men in all, including cavalry and artillery, and carried six light batteries in addition to the big guns bearing riverward. He liked his chances, but he also had to defend a position that had a river at its back, which denied him security for his rear. The Confederates, focusing their attention on the river and the fort’s batteries, thus allowed Grant to reach their positions and make contact with the river both above and below the fort, cutting their communications.

On February 13, the two principal Union divisions, those of Charles Smith and John McClernand, tested the defenses. The day saw heavy skirmishing, artillery duels, and sharpshooter activity. Little was accomplished, however, beyond bloodying raw troops, expending ammunition, and bolstering the morale of the Rebels. Smith was placed on the Army’s left, due west of Buckner’s line, and McClernand on the right, south of Pillow’s line.

McClernand was a political appointee, an Illinois lawyer-politician whose only military experience consisted of a few marches in the Black Hawk War. He was ambitious, untactful, hated West Pointers, and although energetic, had little ability. By contrast, Smith was Regular Army, thrice breveted for bravery in Mexico. A thoroughly outstanding soldier, he had the bearing of a marshal of France. Lew Wallace described him as “a person of superb physique, very tall, perfectly proportioned, straight, square-shouldered, ruddy-faced, with eyes of perfect blue and a long snow-white moustache.”

Planning a Joint Assault

That evening it began to rain, turning to sleet by nightfall as the temperature dropped to 10 degrees Fahrenheit. Troops who had abandoned coats and blankets cursed and spent a miserable night, while wounded men between the lines slowly froze to death. By midnight it was snowing heavily, and the armies awoke on February 14 to a wintry landscape. On the river, Foote and the remainder of his flotilla arrived, bringing with them the bulk of Wallace’s division. Wallace, a newspaper reporter, lawyer, politician, veteran of the Mexican War, and future author of the novel Ben-Hur, was placed in the center between Smith and McClernand. Foote and Grant agreed that the simultaneous assault would begin with the Navy destroying the lower water batteries, then running past them to enfilade the open rear of the fort while the Army surrounded the garrison.

Foote, however, was reluctant to engage his gunboats in attack. Tilghman’s rough handling of his turtles at Fort Henry had undermined his confidence. The Cincinnati and Essex were out of action, and repairs to equipment took time. Repairs to men’s spirits took even longer—they feared being scalded to death aboard his iron coffins. Several of his tars had deserted and replacements balked. He would have preferred to wait a couple of weeks until he had enough men for all his gunboats and some mortar scows as well. Foote could then lay off at long range and methodically demolish the fort stone by stone.

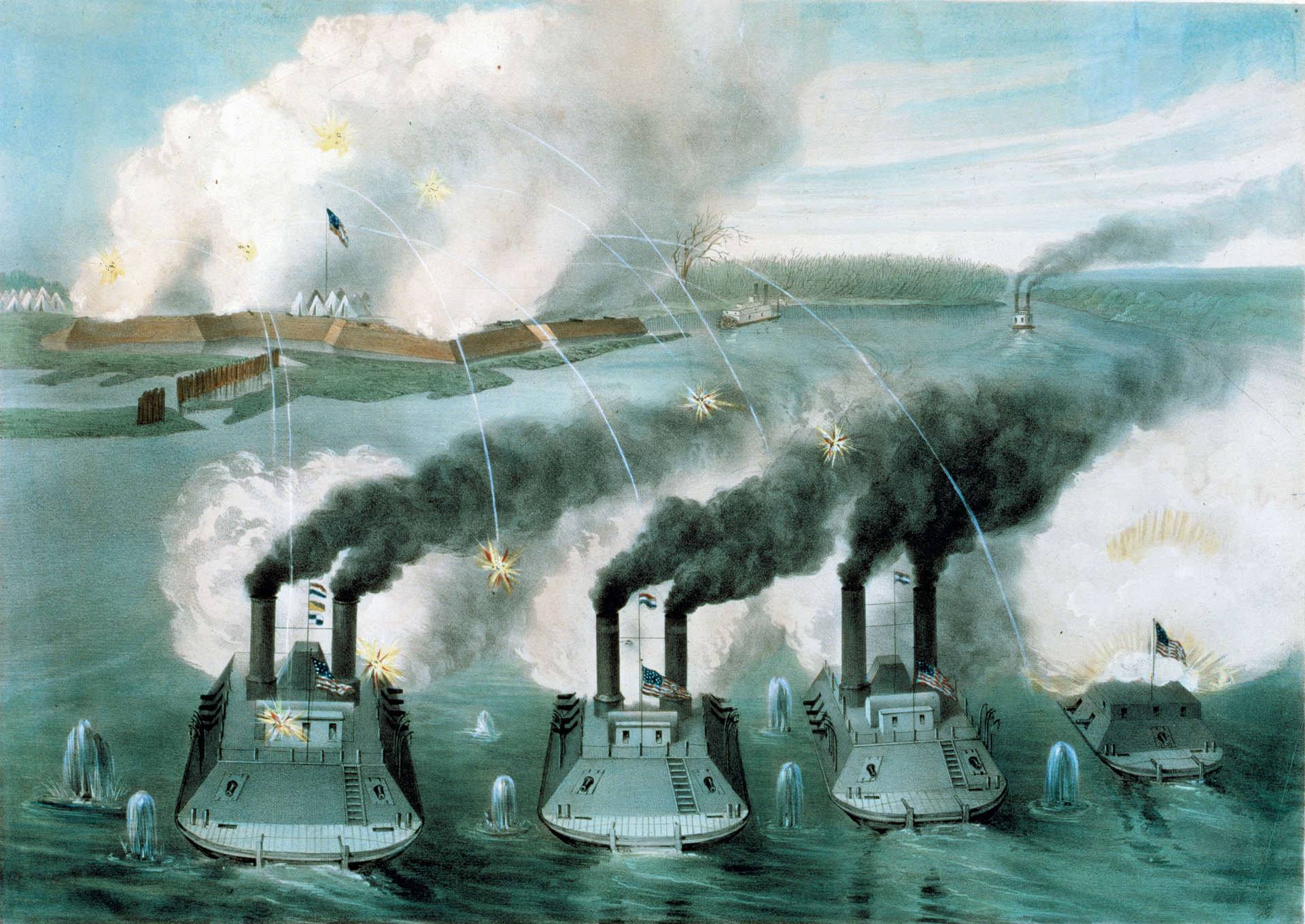

Duty-bound, though against his better judgment, Foote ordered the fleet into the floodwaters of the Cumberland River at 1:45 pm. In line abreast were the ironclads (Carondelet on the starboard wing, nearest the fort, then Pittsburgh, St. Louis, and Louisville), followed by the timberclads, Tyler and Conestoga.

Foote’s Gunboats Assail Fort Donelson

Except for the thudding of the engines and the gurgled screech of a flight of startled geese, nothing broke the profound silence that had settled over the snowy valley. Wrote Walke: “Not a living creature could be seen, only the black rows of heavy guns, pointing down at us, reminding me of the dismal-looking sepulchers cut in the rocky cliffs near Jerusalem, but far more repulsive.” At 2:35, the flotilla came within sight of the fort, and at about 11/2 miles, the Confederates opened the affair by firing two shells to get the range. Both shots fell short, followed by several other misses.

Presently, Foote gave the word and the 8-inch bow gun of the St. Louis blasted forth, the shell dropping just in front of the lower battery. The firing on both sides was slow at first, but gradually became incessant. For a hellish hour the gunboats delivered a heavy and accurate fire, smashing the enemy parapets. Among the onlookers was Forrest, who turned and yelled to his preacher aide, “Parson, for God’s sake, pray; nothing but God Almighty can save that fort!”

A newsman aboard the St. Louis, Foote’s flagship, was more favorable of Confederate chances and thought their fire accurate. Confederate artillery Captain Reuben Ross recalled that “a singular paralysis” took possession of the flotilla. Nonetheless, Foote pressed forward to within 400 yards. Victory was a hairbreadth away; in 200 more yards the ironclads could slip past the Rebel batteries to enfilade the open rear of the fort.

Firing on the Flagship St. Louis

Here their intentions dissolved. Confederate Captain Bell Bidwell recalled that the Union “fire was far more destructive to our works at two miles than at 200 yards. They over-fired us from that distance.” Plunging Rebel fire from the bluffs produced a 30 to 35 degree depressed, right-angle bombardment that smashed into the turtles’ angled sides and unarmored upper decks. Pillow wrote, “I could see distinctly the effect of our shot to one of his boats … when he shrunk back and drifted below the line. Several shots struck another boat, tearing her iron case, splintering her timbers and making them crack as if by a stroke of lightning, when she, too fell back.”

Drawing a bead on the flagship, Confederate Private John Frequa shouted to his mates, “Now boys, see me take a chimney!” True to his word, Frequa’s next shot carried away both the smokestack and flagstaff of the St. Louis. A 32-pound iron ball struck the pilothouse, wounding three men and killing its pilot. Foote, standing next to him, was hit in the ankle, but managed to grab the wheel and continue the fight. Yet the shot had badly damaged the steering mechanism and, unmanageable, the flagship drifted downriver. The commodore then went down to the gun deck to urge on his gunners and help supervise the treatment of the wounded. As he was standing on one side of a gun, a shell struck, knocking down five of the six men manning it and wounding Foote in the left arm.

The Union Navy Repulsed

Next in line for punishment was the Louisville. She took a 32-pound shot that swept her from bow to stern. Then a 128-pound projectile shattered the gun carriage of an 8-inch Dahlgren gun, decapitating three crewmen. Another Columbiad round struck an angle formed by the upper deck and pilothouse. Still a fourth shot, a short shell from the Tyler, severed her tiller ropes. Without steering, she was compelled to drop downriver.

Elsewhere, the Pittsburgh was staggered by numerous hits at the waterline and she began to flood. Her crew could not serve guns and pumps at the same time, so to keep from sinking she retired. Embarrassingly, in retreating, she struck the Carondelet’s stern, smashing her starboard rudder. Only the Carondelet remained in the point-blank fight. Rebel Captain Ross worried that the gunboat, by standing so close to the batteries, would send landing parties to capture the works. Ross claimed everybody determined to sell their lives dearly, using staves, sponger staffs, and handspikes in place of the customary but nonexistent cutlasses.

Ross need not have worried, for within minutes the ironclad was a shambles. Walke recalled that his “vessel was terribly cut up, with the pilot house and smoke pipes riddled, port side cut open 15 feet, and our decks ripped up.” She was struck 54 times, many of these were from cannon balls skipped across the water’s surface aimed at her waterline. Her decks slippery with blood, leaking badly, the final insult came as a 42-pounder cannon burst. Walke had had enough and retired in confusion.

“I Won’t Run Into Fire Again”

Foote’s flotilla had been cut to pieces, the St. Louis hit 59 times, the Louisville 36, and the Pittsburgh 20. He attempted to accentuate the positive, however, by asserting that the gunboat assault “would in 15 minutes more, could the action have been continued, have resulted in the capture of the fort bearing upon us, as the enemy were running from his batteries.” Privately, he was shaken by the pounding he had taken. His wounded foot and arm, combined with the horribly mutilated bodies of his men, had made a profound impression. He felt he had been forced into battle before he was ready and wrote his wife the next day, assuring her that “we will keep off a good distance from the Rebel forts in future engagements. I won’t run into fire again, as a burnt child dreads it.”

Grant was also greatly disappointed at this rebuke of the Navy. He had done nothing in the way of any land diversion to supplement the assault—joint Army-Navy operations had not progressed that far at this stage of the war. The Confederates were jubilant at their decisive blow and were confident they could do the same to the Army. When the euphoria subsided, their commanders understood that they had inflicted little more than a temporary setback. News from them fluctuated from confidence to despair, leaving their theater commander, Sidney Johnston, to send a cryptic and enigmatic wire: “If you lose the fort, bring the troops to Nashville, if possible.”

Planning a Breakout From Fort Donelson

That night at a council of war, the three brigadiers decided that Grant’s stranglehold must be broken. They planned a dawn attack “on our left, and thus to pass our people into the open country lying southward towards Nashville.” However, there were procedural and logistical flaws in the planned breakout concerning the crucial issue of what would happen after a successful attack. Each man left the meeting with a different idea.

Pillow held the belief that his troops would return to the defenses and that victory would be so complete that time would permit retrieval of equipment, rations, and the skeletal units left behind guarding the fort’s trenches during the assault. Then the retreat to Nashville would begin. Buckner and his subordinates thought that nobody would return after the battle, but rather press on to Nashville. In anticipation of this, Colonel John C. Brown’s brigade had packed three days of rations in their haversacks. Floyd, as the senior commander, had the responsibility to make certain that everyone was on the same page. Perhaps at the time he thought they were. In any case, his subsequent actions implied agreement with Pillow’s interpretation of the plan.

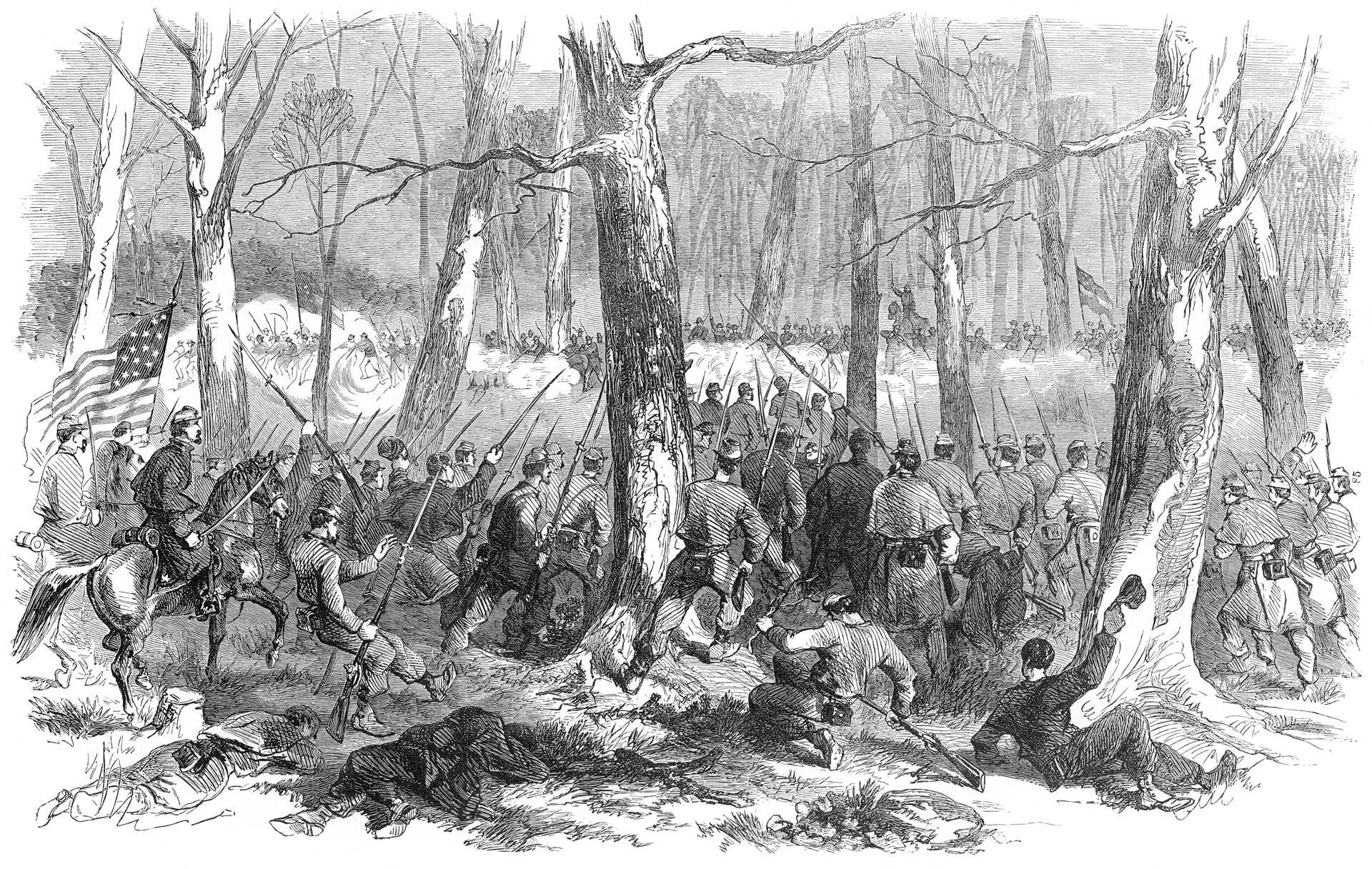

The Rebel Yell

The third day at Fort Donelson began shortly before dawn on February 15, with the high-pitched Rebel yell—“a screeching sound symbolizing men’s frustrations with cold, snow and Yankee bullets, a searching cry for freedom and warm food,” wrote Mississippian John Simmonton. Eight to ten thousand Rebels, with Forrest’s cavalry in the lead, charged toward McClernand’s division. The sudden onrushing Southern tide scattered the sleepy Union pickets and struck with a heavy blow. For the next two hours there were sharp firefights between individual regiments and brigades, slashing thrusts by Confederate infantry and cavalry in combined assaults—and stubborn resistance from determined Federals.

Indeed, the Federals fought well but were simply swamped and outflanked. By 8 am, McClernand was in trouble and called for help. Wallace, whose right flank was exposed as McClernand fell back, sent a brigade on his own authority, while couriers were sent to find Grant. Meanwhile, the mounting pressure from Confederate infantry and cavalry, and the relentless pounding from Confederate artillery, rapidly wore down Union resistance, which was also suffering from dwindling ammunition. Some sectors of the battlefield witnessed vicious hand-to-hand fighting as well as extensive use of bayonets.

In a fight where progress could be measured in yards from hillock to hillock, it was “the spirit and determination that insured success” for the Southern soldier, recalled Simmonton. In fact, after-action reports on both sides were sprinkled with phrases such as “the enemy pressing us very hard,” the ground being “hotly contested,” and the holding of ground “under a galling fire.”

By early afternoon the Confederates had punched a hole in Union lines large enough to march their army through. “Our success against the right wing is complete,” declared Major Jeremy Gilmer. The attack had cleared both the Wynne’s Ferry and Forge roads and the way to Nashville lay before them. Yet, by 1:30 the punch had quite literally gone out of the Confederate breakout attempt. Fatigued soldiers on both sides simply stopped moving as their officers tried to reorganize units broken, mixed, or scattered over the field.

A Paralysis of Confederate Leadership

The lull proved decisive for both sides, for the entire battle changed abruptly. (The results were to be governed by the vital qualities of initiative, character, and leadership.) Pillow, having achieved his objective, immediately ordered the troops back to the trenches to consolidate, pack gear, draw rations, and retrieve the artillery. An incredulous and indignant Buckner at first refused to obey the order. When Floyd arrived on the scene, he was confronted by the irate Buckner. “At his [Floyd’s] request to know my opinion of the movement, I replied that nothing had occurred to change my views of the necessity of evacuation of the post, that the road was open, and I thought we should at once avail ourselves of the existing opportunity to regain our communications.” Floyd seemed to agree, and then rode off to find Pillow. When Floyd found him, he demanded: “In the name of God, General Pillow, what have we been fighting all day for? Certainly not to show our powers, but solely to secure the Wynne’s Ferry Road, and now after securing it, you order it to be given up?”

Using all of his political talents, Pillow sought to convince Floyd of the correctness of his action. Floyd’s decision making seemed as frozen as the bloodstained soil. At this juncture, both generals became immobilized by reports of Union reinforcements, and the irresolution Floyd had previously displayed in West Virginia, together with his tendency to get flustered under pressure, took hold. The Army would return to the trenches.

Confederate Lieutenant Selden Spencer expressed the general opinion among the soldiers at this turn of events: “His [ Pillow’s ] head was turned with the victory just gained, and he was too short-sighted [here Spencer crossed out the words ‘a fool’] to see that it was entirely thrown away, unless we used it for escape.”

“The Position on the Right Must Be Taken”

Grant had risen at his headquarters before dawn, then set off to visit Foote at his anchorage below Donelson, there to see the damaged gunboats. When Grant arrived, the wounded and shaken Foote told him he was taking the gunboats back for repairs. At this point, neither man knew of the attempted breakout of the Rebels south of the fort. Apparently, the sounds of the battle were muffled by the intervening woods and river bends. When the conference ended, a visibly upset Grant was taken ashore where he met an aide, livid with fear, bearing news of imminent disaster.

It was about 1 pm when Grant finally arrived back at headquarters where his staff briefed him on the seriousness of the situation. Remaining imperturbable through it all, he calmly replied, “Gentlemen, the position on the right must be retaken.” He correctly perceived that the Confederates had done their worst. Grant also reasoned that the strength of the Confederate attack meant that they had weakened their right, concluding that “the one who attacks first will be victorious.” With that he proclaimed, “General Smith, all has failed on our right, you must take Fort Donelson.”

“I will do it,” was Smith’s simple reply. With much energy and precision the 60-year old general—who had been commandant at West Point when Grant was a cadet—deployed his troops, and by 2:35 all was in readiness. Smith, sword held aloft with hat on blade tip, his long white moustache flowing in the wind, was the stuff of heroic paintings. “You must take the fort; take your caps off your guns, fix bayonets, and I will lead you,” he bellowed. Lead them he did, but regimental formations became ragged crossing incorrigible obstructions, and confusion attended the ascendance of a slippery slope into the Rebel abatis. Then came a murderous fire that struck down 400 of the bluecoats. Nevertheless, Smith and his soldiers pressed forward. By 3 pm, they had cleared out the Rebels on the left and had cracked Fort Donelson’s outer defense line.

Wrote Captain Seth Leyard Phillips, USN: “Do you know that our army was at one time defeated before Fort Donelson & General Smith—one of the first soldiers of our country—retrieved the fortunes of the day by leading his brigade to the charge of the chief redoubt, himself the first man in it! It is no stretch to say that defeat or victory hung upon his life & heaven guarded him in the terrible fire that for a while was forced upon him and his command.”

A Victory “Complete and Glorious”?

Meanwhile, Wallace was encountering feeble resistance reclaiming most of the ground on the right. He found Confederates withdrawing from positions gained at great cost only hours before. As the sun sank, the fighting dwindled.

Another bitterly cold night ensued, but Grant took advantage of the hours by moving up artillery and reinforcements to positions won by Smith and Wallace that commanded the whole Confederate defensive works. Inside the fort, Floyd and Pillow fatuously wired Johnston in Nashville that they had won a victory “complete and glorious.” In time, a clearer picture began to emerge. The Confederate officers began to realize the hopelessness of their situation; the fort could not be held nor could its troops now escape to Nashville. They resolved to surrender. Upon learning of the planned capitulation, Forrest exploded in anger. Insisting there was more fight in the army than the generals gave it credit for, he announced to his troopers, “Boys, these people are talking about surrender and I am going to go out of this place before they do or bust hell wide open.” Accordingly, he started to make his plans.

Also during the night occurred one the most comic and shameful episodes of the war. Floyd abdicated his command to Pillow; then Pillow abdicated it to Buckner. Floyd escaped by river with a few of his regiments, while Pillow fled in a small boat. On a more heroic note, the wily Forrest managed to cut his entire command out of the trap. They rode through swamps of ice-cold water until they reached safety.

General Buckner’s Surrender

Early the next morning, February 16, the hapless but responsible Buckner sent word to Grant that he desired terms of surrender. Grant’s answer to his old friend and classmate not only made Grant famous, but gave impetus and direction to the whole war: “No terms other than an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to immediately move upon your works.” Buckner petulantly replied that he found the “ungenerous and unchivalrous” offer insulting, but he had no choice. Either by siege or starvation, surrender was now inevitable.

Although its strategic impact gave the battle at Fort Donelson significance, Grant had also attained one of the major tactical successes of war. His own casualties in killed and wounded were slightly more than those of the Confederates, but his total casualties amounted to only 2,832 or 10.5 percent of his 28,000 men. Because of the surrender, Confederate losses totaled 16,623 or 79 percent of their 21,000 men.

Grant had thus virtually annihilated an enemy army by cutting his opponent’s communications by pinning him against a river. In spite of Halleck’s excellent strategy and good management and Grant’s energy and ability, the eminent 19th-century military theorist Karl von Clausewitz had foreseen that such a victory could not have taken place without “major, obvious, and exceptional mistakes on the enemy’s part,” as when the Confederate command had divided its forces and placed Floyd’s command where Grant could so readily trap it.

Taking the Heart of Tennessee

The fall of these two forts ensured the collapse of the entire Rebel line across Kentucky and propelled Grant into the limelight as the North’s premier commander. Indeed, the Henry and Donelson fights marked the first turning point of the war, because what followed in the next few weeks was a series of Union triumphs, several directly or indirectly attributable to the falls of the two forts. These losses left the western Confederacy struggling for its life.

First among these triumphs was the capture of Nashville, the first major Confederate city and first Confederate state capital to fall. Abandoned a week after Fort Donelson surrendered, this was a serious blow, since Nashville was not only the western Confederacy’s most important city for manufacture, but also a major arsenal and supply depot. The total loss of middle Tennessee amounted to much more, as the state was the greatest iron-ore-producing region in the Confederacy. The heart of Tennessee’s growing industrial complex and its great war potential were gone. The loss of the two forts effectively rocked the Confederacy to its core.

Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, wrote: “The cause of the Union now marches on in every section of the country. Every blow tells fearfully against the rebellion. The rebels themselves are panic-stricken … or despondent. It now requires no far-reaching prophet to predict the end of this struggle.”

Robert Henry, in his book Story of the Confederacy (1931), echoed these thoughts when he wrote, “Fort Donelson, in many ways, may be considered the critical event of the Civil War.” More recently (1987), Frank Cooling, in a study of the fall of the two forts, wrote of “the expedition that broke open the West.” Bruce Catton further opined that “Fort Donelson was not only a beginning; it was one of the decisive engagements of the entire war, and out of it came the slow progression toward Appomattox. n

Very good article, most enjoyable. Should you want to learn more about this region and the effects on the citizens which lived in what is now known as Land Between the Lakes, a National Recreation Area, may I recommend Jack Hinson’s One-Man War.

With Dover, TN being the largest city in the lower region, the book tells about how citizens sought to be neutral and carry on with their lives. But, Union troops pillaged and captured all men of age, murdering many in the process. As pointed out in this article the terrain is all but impassable, very little tillable land, and very hilly (not mountain’s so to speak just up and down)

With the capture and murder of his son’s Jack Hinson sat out on a vengeful One Man War by sniping from these hills and bluffs along the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers and did such a good job at it his efforts put caution into any boat running either waterway. Great book which details the capture of both forts and the effects upon the region, going from a quite Southern farming community to becoming ‘occupied’ by Union Troops.

An aside: Having been a delivery/charter captain I have traveled both of these Rivers extensively. Having gone to University in Clarksville, the first city after Dover taken by the Union Western offensive, I have traveled the Land Between the Lakes extensively. Reading this article and the mentioned book I have been there, I know the places described. If you are a Civil War fan, get a copy of Jack Hinson’s One-Man War. You’ll be glad you did.