By John W. Osborn, Jr.

On the night of April 8, 1940, almost four million people went to bed at peace in the midst of a world war. By the time they were having breakfast, they found themselves in the middle of it, and Denmark’s resistance, as little as it was, was already over. The German invasion of Denmark in World War II was the swiftest military conquest in history—less than three hours—but still had moments of high drama.

“I could not reproach Denmark if she surrendered to Nazi attack,” British Prime Minister Winston Churchill conceded. “The other two Scandinavian countries [Norway, Sweden] have at least a ditch over which they can defy the tiger. Denmark is so terribly close that it would be impossible to defend her.”

Denmark was just 250 “terribly close” miles from Berlin itself, its 42-mile border with northern Germany indefensible. The Jutland Peninsula, extending 200 miles into the Baltic Sea and making up 70 percent of Denmark’s mere 16,629 square miles, with its very flatness was ideal for the type of military maneuvering the Germans had just perfected in Poland: blitzkrieg, or lightning war.

The rest of the country was a geographic jigsaw of 500 islands, just 100 inhabited, none any more defendable than Jutland. Most of them were linked by skillfully constructed bridges, including the key two-mile Storstrom, connecting Masnedo Island with Sjaelland, and on it, the capital city of Copenhagen. The population was too small to build a significant army, and the last time the country had fought a war was in 1864, ending in a defeat by Prussia.

“I have not the slightest doubt that the Germans will swarm all over Denmark when it suits them,” Churchill concluded. “I would not in any case undertake to guarantee Denmark.”

Such pessimism also ran all the way to the top in Copenhagen. “Denmark is not the watchdog of Scandinavia. What is the point?” asked Prime Minister Thorvald Stauning. He and the equally depressed and desperate foreign minister, Peter Munch, had to pin their hopes—and Denmark’s fate—on a non-aggression pact with Germany. By the time it was signed on May 31, 1939, though, Hitler’s blatant violation of the Munich Pact and march into Prague two months earlier left no doubt what Hitler’s word was worth.

Back in 1937, a Danish colonel complained, “From the German view, we do actually invite occupation.” Stauning and Munch made it appear even more so after the outbreak of war, actually cutting Denmark’s army in half to just 15,450 by April 1940, 7,840 of them conscripts with just two months service.

If they wanted to show Hitler that Denmark was no threat, they also showed it would be no problem if the time for invasion ever came. Eventually, Hitler would find a pretext to invade through an incident the Danes had no control over, and Germany’s seizure of Denmark would provide a steppingstone to invade another country that was the real German target.

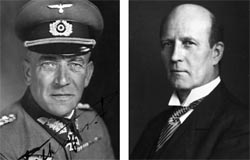

“It is in our interest that Norway remains neutral,” General Franz Halder, chief of the German general staff, recorded in his diary on New Year’s Day, 1940. The Germans were satisfied, so long as badly needed iron ore from Sweden could be shipped from Norway’s northernmost port of Narvik then sailed safely down its frozen fjords to Germany.

Halder nonetheless observed ominously, “We must be prepared to change our view on this, should England threaten Norway’s neutrality.”

From the German point of view, the Royal Navy did just that, ignoring Norwegian sovereignty to enter its waters to storm the German supply ship Altmark, liberating almost 300 British merchant seamen held captive in its hold.

The British would say the Germans committed the first violation when they did not release the prisoners once in neutral waters, and the Norwegians were complicit by not insisting, though the prisoners’ banging and yelling was plain to hear. The incident was enough for Hitler to order Norway occupied and, as an afterthought, Denmark as well.

Danish airfields were recognized as vital for any Norwegian campaign. The initial planning envisioned putting diplomatic pressure on the Danes to use them—overlooking the fact that their king, Christian X, and Norway’s own king, Haakon VII, were brothers—but the general in charge of the campaign, Nikolaus von Falkenhorst, insisted on occupying Denmark as “a land bridge” to Norway.

The first Germans to invade Denmark came in the guise of tourists, a more familiar form of foreigner.

One walked along Copenhagen’s bustling Langelinie (Long Canal) in the city’s center, then made his way to the Kastellet, the 16th-century fortress, and in a different era, Denmark’s Pentagon. He asked a sergeant for a “tour” of the fortress. “He complied with my request in the friendliest manner,” the “tourist” was to remember. “To start with, he took me to the corporal’s canteen where I drank a glass of beer with him. At the same time, he told me something of the Citadel, its garrison and importance. After some beer with him, he showed me the quarters of the commanders, the military offices, the telephone exchange, the watch posts, and the old gates by the north and south entrances.”

With the tour over, the German flew home. He would be back in five days—on business.

Other “tourists” were curiously occupying themselves with some of Denmark’s decidedly less scenic sights, such as Masnedo Island and the Storstrom Bridge. In a local bar, they heard talk about the island’s forts guarding the bridge, itself guarded by “white Italians.” A special military unit? The “tourists” took note, gathered intelligence, and reported the military mystery to Berlin, with comic consequences to come.

While Danish officials tried to be hopeful, Danish officers were learning how hopeless their situation really was. Major Hans Lunding ran a spy ring in northern Germany, which sent him reports of troop concentrations, increases in military traffic, and the stockpiling of supplies. In Berlin, the Danish naval attaché got word from the Dutch military attaché, who had gotten it from an anti-Nazi officer in the Abwehr (German intelligence). “Denmark will be occupied next week.”

On April 7, one final German “tourist,” General Hans Himer, arrived by train, his soon-to-be-needed uniform in protected diplomatic luggage.

Himer was not there to see the sights so much as to have the city in his sight, proceeding to make a busy day of it, walking the Langelinie to note if it was ice free, next circling the Kastellet and finding its weakest point at the southeast King’s Gate. He phoned the information in code to Hamburg, then finally arranged for a truck to be on the Langelinie in two days—at the odd hour of 4 am.

The next day, the British made their own move regarding Norway, mining its territorial waters. Though it was a Sunday, Foreign Minister Munch met with the longtime German ambassador, Cecil von Renthe-Fink. He was an honorable Hindenburg-era holdover, too long comfortably cocooned in Copenhagen.

“Hitler has no warlike intentions toward Denmark,” Renthe-Fink genuinely believed, and he reassured Munch, who remained optimistically obtuse to the very end. In just hours, they were to have a shattering, shocking, revolting return to reality, Nazi-style.

A day earlier, German airborne commander Walter Giercke had his own meeting in a local headquarters in Hamburg housed in a requisitioned hotel following an emergency summons to fly immediately from his base in Stendahl. He found himself in a room full of nervous generals, facing a major with a map covering the wall behind him.

“See this bridge?” the major pointed to the map. It was the Storstrom. “We’ve got to capture this bridge intact. If you were dropped, do you think you could hold it until infantry arrives?”

Captain Walter Giercke was being handed the first airborne operation in history!

It was a last-minute addition to the invasion because of the report of those unknown “white Italians.” Though all he had for intelligence were a brochure and a postcard taken during a “tourist” visit, Giercke assured them that there would be no problem. “The relief of the generals surrounding me was palpable,” he recalled after the war.

Throughout the preceding Sunday, German warships were sighted off Jutland. Truck drivers coming back from Hamburg reported rolling past German troops for 30 miles. At the border, a journalist phoned his editor in Copenhagen, telling him of hearing the unmistakable sound of armor in the distance from his window.

Major Lunding had sent in his final report, predicting an invasion at 4 am. In Berlin, that alert naval attaché got a suspicious offer from the Germans to tour the Western Front, seeing it as a sign that they wanted him out of the way. At a banquet inside Copenhagen’s Amalienbord Palace, by contrast, the 70-year-old King Christian X, who had ruled since 1912, dismissed talk of war, heading off to the Royal Theater to laugh his way through Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor.

It was the last good laugh for the king for five long, dismal years.

Captain Giercke was preparing his part to make them so back at his base. “The parachutes were packed, the ammunition supplies and the weapons laced in their containers,” he wrote soon afterward. “Everything took place quickly under the cover of an alert exercise. The atmosphere was not tense, but rather ordered and tranquil. Activity on the runway was unceasing: trucks were supplying planes, Fallschirmjäger with their parachutes ready were awaiting orders, and engines were being checked. More aircraft arrived: Stukas and bombers. Finally, the paratroopers boarded the aircraft, which began to move down the runway. The squadron commander reported that his unit was going to make a “practice flight over the sea.” The airfield was abuzz with activity in the noticeably tense atmosphere, and everyone was at his post. The support and air defense were essential. The canteens were packed, and songs and marches could be heard everywhere.

“Only the platoon commanders, together with their company commander, remained in the barracks–they knew the truth about the ‘exercise,’” Giercke continued. “They also knew once they received the code word, they could discuss the mission assigned to them. This did not take long in coming. That same afternoon, orders were given to the troops. The sergeant major gathered the company. The men listened attentively to their commander: ‘The Führer has decided to attack Denmark and Norway in order to protect the Reich. We have received the order to occupy Denmark tomorrow.’”

Beginning officially at 4:15 am, April 9, 1940, the invasion of Denmark had secretly started hours before under cover of darkness with Abwehr agents cutting communications while special forces seized bridges along the border, which the nervous Danish government in the days before had pulled troops from to avoid any excuses for invasion. But it was also begun by a cruel display of diplomatic deceit.

Fifteen minutes earlier in Copenhagen, Foreign Minister Munch was awakened in his ministry apartment by a call informing him that Renthe-Fink was already on his way for an urgent meeting. Munch had just enough time to throw on a suit when Renthe-Fink arrived, the diplomat with tears in his eyes. The night before, General Himer had handed him a sealed envelope with instructions to deliver it at this odd hour, and he did not have to read it to know its contents.

Munch soon understood the diplomat’s distress.

“The Reich government has beginning today set in motion certain military operations which will lead to the occupation of strategic points on Danish soil,” Renthe-Fink announced. “The Reich government,” he droned on, “declares to the royal Danish government that Germany has no intention of through her measures now or in the future of touching upon the territorial integrity and political independence of the Kingdom of Denmark.”

Both men were bitterly aware of what those words were worth. Renthe-Fink left, calling Hitler “a man without honor,” as his own government had used his personal honor. Frantically phoning Amalienborg but getting no response, Munch had to rush to the street, hail one of the few cabs out that early, then speed off for the king.

At that moment, the German 170th and 198th Infantry Divisions and the 11th Motorized Rifle Brigade, 40,000 troops in all, were pouring over the bottleneck border with Jutland, eventually driving 25 miles north. The three border guards attempting to resist had been shot.

There was even less resistance to seaborne landings around the peninsula. At one location, Danish soldiers helped dock a German patrol boat, at which point the soldiers crammed below stormed out. Elsewhere, a Danish garrison specially trained to resist a German landing slept while it was happening.

“The availability of tanks and armored cars was the greatest importance,” one German officer said. “They broke the first Danish positions.”

Denmark had, improbably, manufactured some of the best 20mm and 37mm antitank guns in the world. In pockets of not more than 30, Danish soldiers in Jutland’s little towns and roadsides quickly constructed roadblocks of felled trees and handcarts, then fired away with them. “Not smart in appearance, perhaps, but they are tough and crack shots,” a German colonel conceded about these determined, scrappy Danes.

They would actually knock out a quartet of tanks and a dozen armored cars. In 2005, the archives of the Danish gun manufacturer revealed that the Germans admitted they had 200 casualties in those few hours in Jutland, contradicting the legend of no resistance by the Danes. After firing, the Danes were either quickly surrounded or retreated into the towns to trade shots around corners in the back streets.

One company of Danish troops escaped, taking the regular morning ferry to Sweden. Another German attack was to come from the sky, aiming to make military history but ending as just a farcical footnote.

Captain Giercke was en route to his target, the Storstrom Bridge, with its supposed white Italians. “Everything was ready to go,” he wrote of the preparations. “The engines were repeatedly checked. The soldiers moved like shadows on the runway. Slowly, imperceptibly, the night gave way to the dawn, which brought a sense of relief to the captain of the transport squadron. The sun would be up in an hour. The light at this time of day made it almost impossible to distinguish sky from the sea in the mix of clouds and darkness. We took off soon after, sheltered within the gray darkness of the morning. The Danish coast appeared like a shining strip. The antiaircraft fire shone, too. The sun appeared like a gigantic red ball above the horizon. Below us were large houses, which appeared empty and asleep, the seas around us occasionally dotted with small boats. Suddenly, the large bridge appeared. A huge construction, we were upon it in no time. The aircraft continued descending, and we saw land again, the island of Masnedo. We could also see the road, as well as the railway line which crossed the island. Soon after, a chimney appeared. Finally, we got the signal: ‘Jump!’”

Giercke and his Germans did jump from 500 feet at 5:35 am, 20 minutes behind schedule. He wrote of storming the local fort: “The Danish sailors came out with their hands up and legs shaking, fear written on their faces.” In fact, though, all the Danes he found were a civilian caretaker, Henry Schmidt, and Privates Adolf Kernwein and Ole Jensen. Their sole weapon was an obsolete Remington rifle with no bullets.

The Danes had abandoned the fort some time earlier. Those “white Italians” the Germans had been concerned about turned out to be chickens, a breed kept by caretaker Schmidt.

Grabbing bicycles, the paratroopers pedaled down to the bridge, captured it without resistance, and soon, as planned, linked up with advancing Wehrmacht units. A second airdrop 45 minutes after Giercke’s captured a more critical target, the airfield at Allborg on Jutland’s northern tip. The capture of Copenhagen soon followed.

At the time Ambassador Renthe-Fink and Foreign Minister Munch were facing each other, a German passenger ship turned troop transport, the Hansestadt Danzig, was sliding unimpeded through Copenhagen Harbor. The commander of the harbor fort attempted the gesture of firing a warning shot, but winter had frozen the gun’s grease. The only other resistance that day in Copenhagen would prove to be deadlier in its soldierly symbolism.

The Hansestadt Danzig continued on to dock at the Langelinie, and in front of the few astonished dock workers already at work, 850 German soldiers trooped down the gangway, and at their head, that “tourist” back now on “business.”

The Germans split into three columns, two headed for the Kastellet, the last for Amalienborg Palace. One gate at the Kastellet was blown down by a premature explosion, killing a German soldier. The Germans simply walked through the others, outnumbering the guards. The structure, garrison, and Danish chief of staff were taken without a shot. General Kurt Himer, who had been directing events from his hotel telephone until the Danish postal authorities finally cut him off, was soon back in touch with his forces in Denmark and headquarters in Hamburg when a truck transported from the Hansestadt Danzig arrived with radio equipment.

Two other more desperate officers were on the move around town. The Danish commander in chief, General Walter Wein Prior, had left the Kastellet scant moments before the Germans had barged in, headed for the War Ministry. Prior met his naval counterpart, Vice Admiral Hjalmar Rechnitzer, who would have been the controversial figure of the day’s events, except there would never be anyone to argue for his side. Prior phoned to put Denmark’s air force, only 48 planes, into action. Just one managed to get airborne, helplessly downed in minutes, the pilot and observer killed. Half the others were quickly damaged or destroyed on the ground, while a single unfortunate Messerschmitt Me-110 fighter would be the Luftwaffe’s lone loss, downed by antiaircraft fire. The pilot and his crewman survived. As they became the sole prisoners taken by the Danes throughout the war, another German pilot landed, got out, thanked the Danes who were taking care of them, and then took off. The Danes were too surprised to take a third prisoner.

Meanwhile, Prior and Rechnitzer had made their way to Amalienborg to find their civilian counterparts, who were scared by the sound of scattered shots outside and on the phone with Ambassador Renthe-Fink in desperate dialogue. The German diplomat warned that Copenhagen would be bombed if the Danes did not surrender. The Danes replied that they needed their king’s consent. A few minutes later, another phone call gave rise to the day’s most controversial conversation. It came from the naval headquarters, requesting authorization to start firing.

With the crisis looming, Rechnitzer had sent some of his best commanders on sudden leave the day before. Now he, in effect, put the whole Danish Navy on leave. Without consulting his counterpart, the cabinet, or the king, Rechnitzer gave the order not to fire. At that, Prior erupted in a burst of fury, and the outrage was not to end with just him.

Outside the king’s palace, at 6 am, 20th-century German soldiers in field gray uniforms faced Danish Life Guards arrayed in Napoleonic-era uniforms domed with bearskin shakos. In a brief firefight, six Guards were killed, a dozen wounded. Surprised at the unexpected resistance, the Germans scurried off to prepare for a stronger assault, but it never took place. Inside the palace, the shooting had reduced the cabinet to pure panic. Their state of mind would improve when King Christian finally appeared.

The merry monarch of the night before was now a miserable one, pale, trembling, likely in shock, close to fainting. “Have the troops fought for long enough?” he helplessly asked General Prior.

“The troops have not fought at all!” Prior angrily answered, unaware of the scattered resistance across Jutland. “Take the government to the Hosraeltelejren military base and make a stand there.”

But Prior proved to be the lone voice of resistance. Outside, German Heinkel bombers escorted by Messerschmitt fighters were overhead, requested by Himer to drop leaflets. “Roaring over the Danish capital, they did not fail to make their impression,” Himer would note smugly. A raid was narrowly averted, called off just in time after a code was misread and thought to be authorizing the bombing.

The king finally decided it was hopeless to continue, so at 6:35 am a messenger left to deliver the capitulation to Ambassador Renthe-Fink. In their final humiliation, with no local radio on the air yet, the Danes had to resort to using the Germans’ own radio equipment at the Kastellet with a Danish wavelength to broadcast the cease-fire order to their soldiers and sailors.

Final resistance ended around 7:20 am, April 9, 1940, so while the Danes were having their breakfast, the blitzkrieg in Denmark drew to its conclusion. Ambassador Renthe-Fink and General Himer appeared at Amalienborg at 2 pm to put the finishing touches on Denmark’s debacle.

“The 70-year-old King appeared inwardly shattered,” Himer recalled. “Although he preserved outward appearances and maintained absolute dignity during the audience. His whole body trembled. He declared that he and his government would do everything possible to keep peace and order in the country to eliminate any friction between the German troops and the country. He wished to spare his country further misfortune and misery.”

Himer responded with assurances of German goodwill, though both knew, with the non-aggression pact so callously cast aside, that it would only last only as long as it suited Hitler. At the conclusion, the king, in his own attempt at goodwill, remarked, “General, may I, as an old soldier, tell you something as soldier to soldier? The Germans have done the incredible again! One must admit it is magnificent work!”

It was the last show of kingly courtesy Christian X was to show the Germans.

“My mood is quite black, and I feel extremely dejected and heartbroken,” Admiral Rechnitzer wrote. “It all seems so extremely sad to me.”

But it was sadder for the families of the 16 Danes who died and the 23 wounded resisting the invasion. There were two additional career casualties: Rechnitzer, scorned by his officers, and Foreign Minister Munch, who was to resign within weeks, his reputation equally in ruins.

Danes that morning walked among the Germans in a mixture of curiosity and shock. “In Prague, they spat at us. In Warsaw, they shot at us. Here, we are being gaped at like a traveling circus,” a German officer commented.

The dismayed Danes vented their anger elsewhere. “You can look anyone in the face, with your heads erect, knowing you have done your duty,” General Prior said in a message to his soldiers, but in the streets of Copenhagen, they were spat on.

The contempt spread abroad, fueled by the scenes of curiosity fraudulently presented by the Germans as friendly fraternization, announcing no casualties to give the image that they had been unopposed. In the United States, Danish naval cadets were jeered in ports while a boxing commentator complained how a one-rounder had gone down “without fighting—like a Dane.”

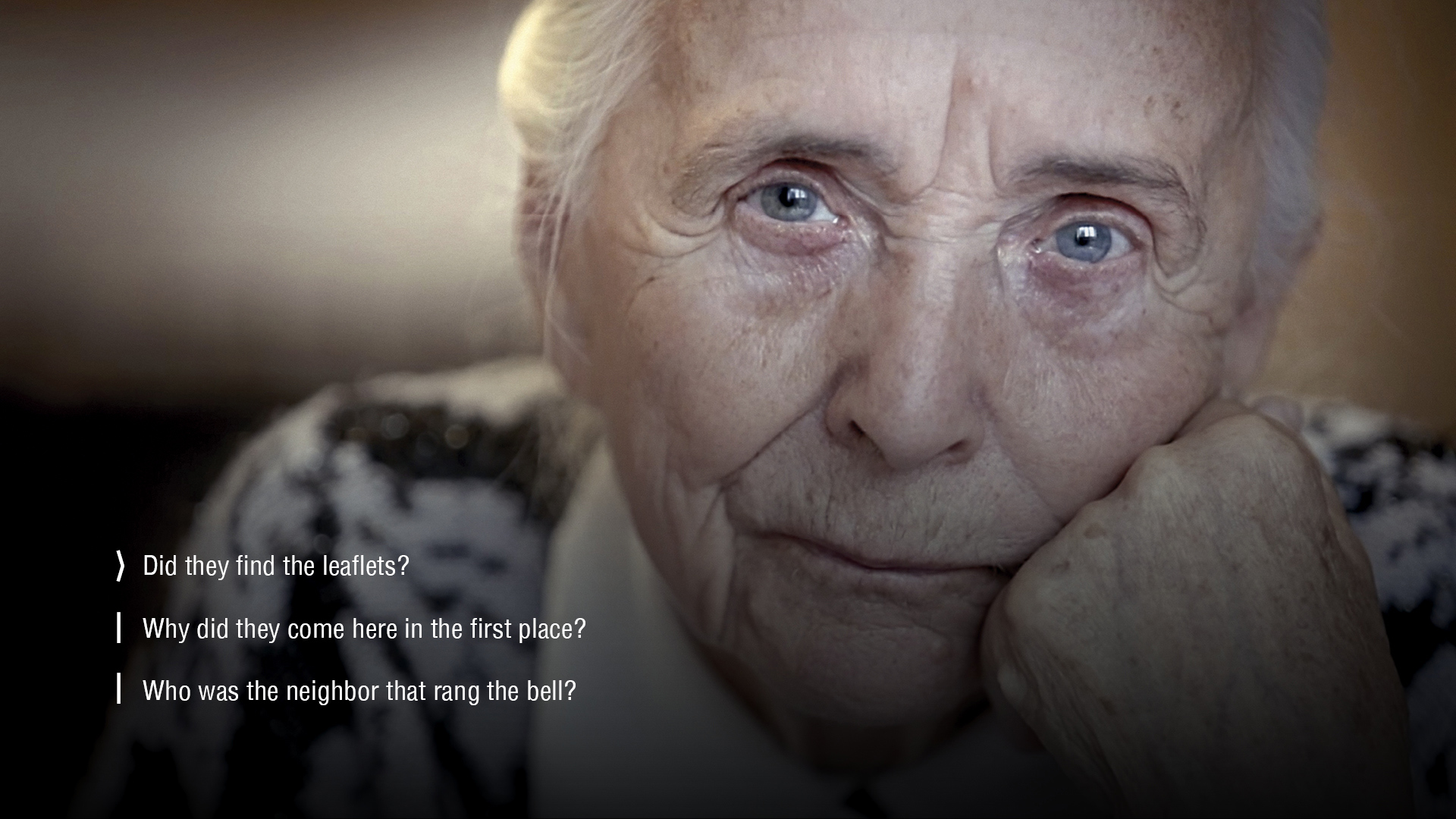

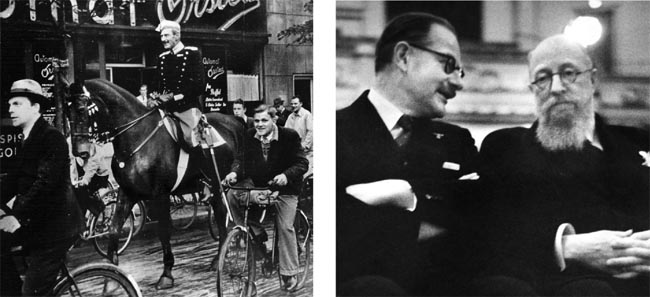

In 700 pages of postwar writing, Prime Minister Churchill gave the invasion one line: “Denmark was easily overrun after a formal resistance in which a few faithful soldiers were killed.” In the next five years, though, Danes were to show that if they could not fight, they could resist. The king set the tone the following morning on his customary horseback ride through the streets of Copenhagen. He refused to return a single German salute.

Danes got the message about how to act toward the Germans. It would slowly dawn on the Germans just what was behind the veneer of customary Danish courtesy. “To the Danes,” the Times of Londonobserved, “belongs the credit of inventing a new order unthought-of by Hitler: the Order of the Cold Shoulder.”

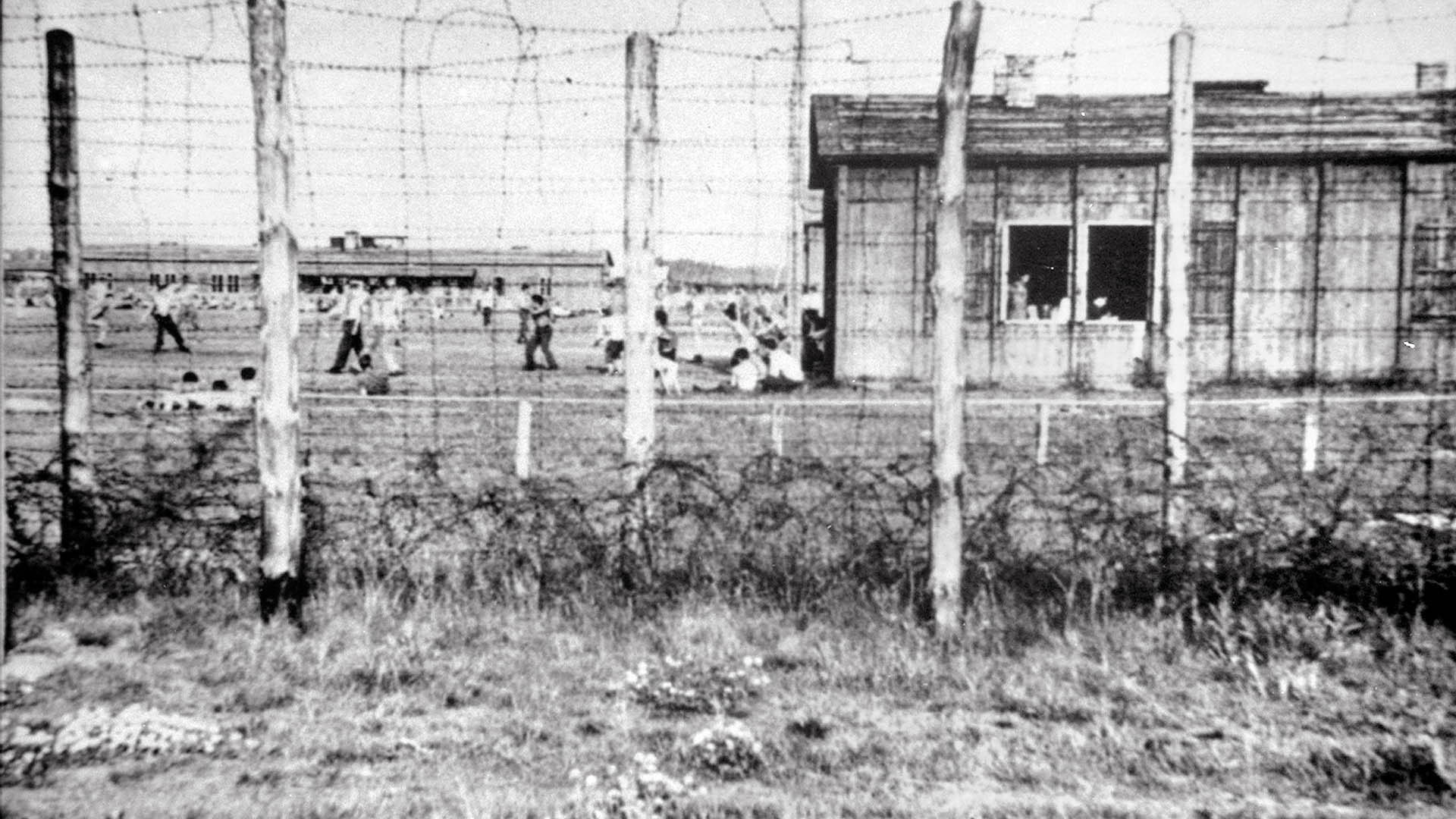

The cold shoulder soon turned to sabotage, eventually requiring three times the German soldiers to occupy Denmark as to conquer it. The Germans, under what they called their “model protectorate,” allowed the Danish courts and government to function, even leaving the schools and press alone. The Germans even allowed the only free election in occupied Europe in 1942, expecting the local Quisling party to be voted in.

The result was another Danish rout—of the collaborators, who received just three percent of the vote. The inevitable confrontation came in August 1943.

The killing of a Danish Resistance member led to a general strike, paralyzing all of Denmark while 200 acts of sabotage occurred. Fed up, the Germans handed the government an ultimatum with a seven-hour deadline. When it was rejected with just 15 minutes left, the Germans dismissed the fiction of the protectorate, imposed martial law, confined the king in his palace, dismissed the government, and moved against the Danish military. Danish troops prepared to resist, but their commander in chief, General Ebbe Goertze, ordered them not to fight. The Danish Navy in Copenhagen Harbor scuttled 29 vessels while 13 escaped to Sweden.

A few weeks later, in one of the war’s great acts of resistance, the Danes smuggled almost their entire Jewish population to safety in Sweden. Sabotage continued, and the Germans reacted ruthlessly, with more than 1,000 Danes murdered in the streets or even in their homes by terror gangs of Gestapo agents or criminal collaborators. More Danes were fated to die but, ironically, some would die while in German uniform.

Some Danes fought as volunteers in the Waffen SS on the Eastern Front, and one single bloody day, June 2, 1942, Danish SS casualties exceeded those incurred resisting the invasion of their own country by 21 dead and 58 wounded. When they returned, it would be their turn to be insulted, booed, and jeered parading through Copenhagen.

If Denmark’s invasion was almost bloodless and its occupation bloodier, its liberation came without bloodshed. The German Army in northwestern Europe surrendered to Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery’s forces in May 1945, and the German troops in Denmark simply walked out. The Danes vowed, “Aldrig mere 9 April” (Never Again an April 9) and abandoned neutrality to help found NATO in 1949.

Author John W. Osborn, Jr., is resident of Laguna Niguel, California. He has written for WWII History on a variety of topics.