By Mark Simmons

The River Mersey was fog shrouded on the morning of November 6, 1865, and the city of Liverpool was scarcely visible from the deck of the CSS Shenandoah. Only the spire of St. Nicholas, the sailors’ church, could be glimpsed above the fog. After an epic around-the-world cruise of 58,000 miles, the Confederate commerce raider had finally come to anchor astern the HMS Donegal. Cornelius E. Hunt, one of Shenandoah’s young master’s mates, recalled that they were not sorry to be obscured from the shore by the fog, “for we did not care to have the gaping crowd on shore witness the humiliation that was soon to befall us.” The ship’s war, like that of the nation she had served, was coming to an end—nearly half a year after the fighting already had ended on land.

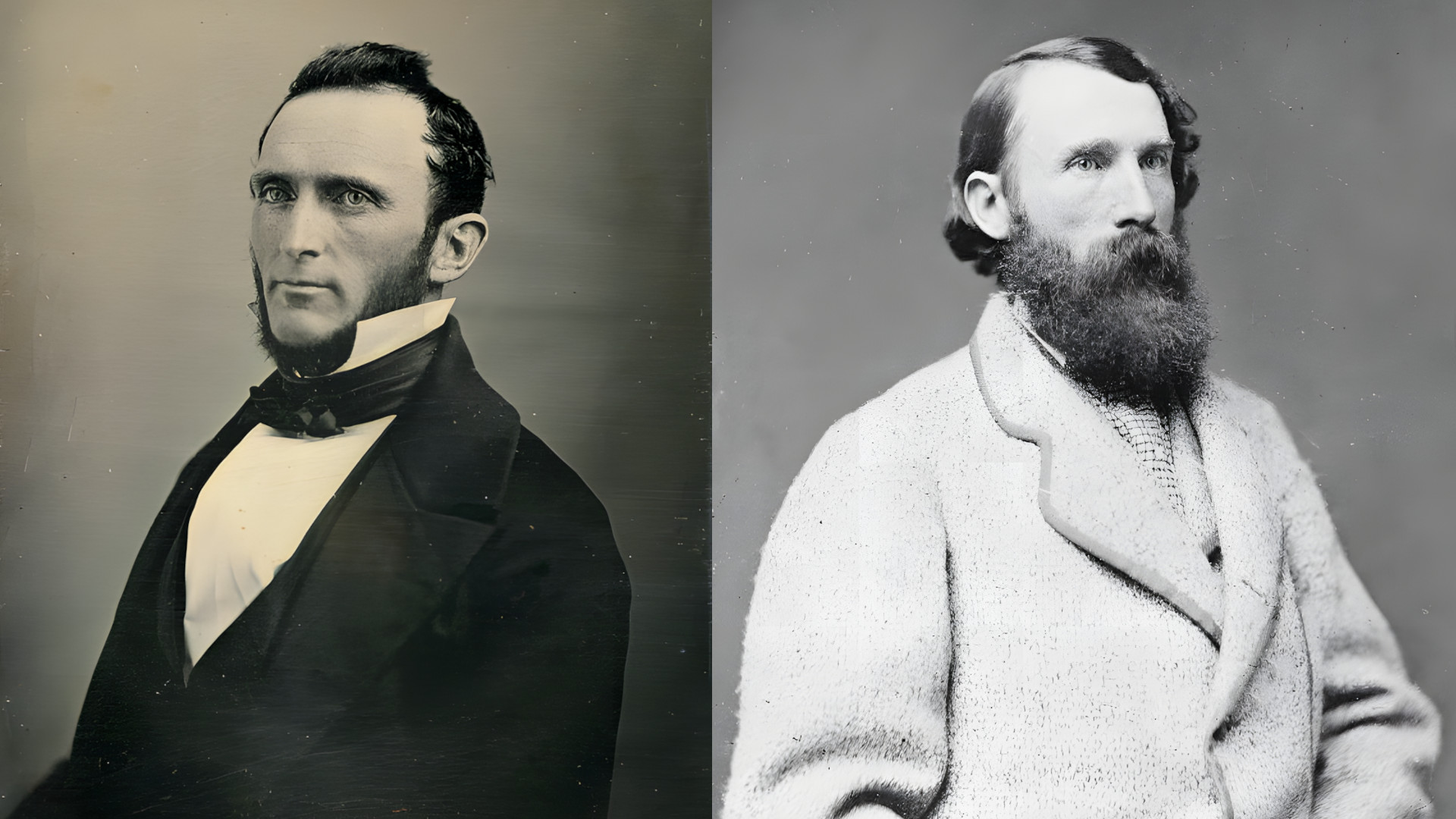

The birth of the Confederate Navy had taken place 41/2 years earlier in Montgomery, Alabama, then the provisional capital of the new Confederate States of America. Secretary of the Navy Stephen R. Mallory said the new navy at first consisted merely of an unfurnished room in the city. Mallory was fortunate, however, to have at his disposal several experienced former United States Navy officers. One was 38-year-old James Dunwoody Bulloch, who came from a prominent Georgia family and had spent much of his life at sea.

Creating the Confederate Navy

When the Southern states seceded, Bulloch quickly settled his business affairs in New York City and headed south by a roundabout route to avoid suspicion. He offered his services to the Confederacy via his friend Judah Benjamin, who would become attorney general of the new government. Benjamin in turn recommended Bulloch to Mallory. On May 7, 1861, Bulloch met with Mallory, who told him, “I want you to go to Europe. When can you start?”

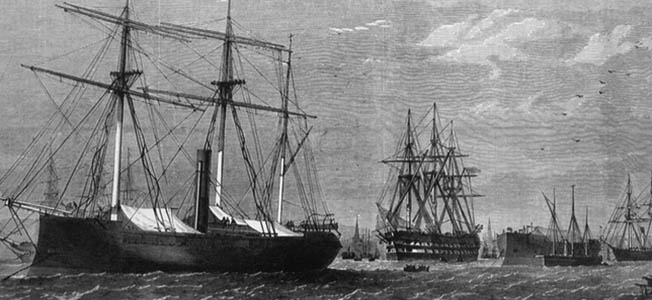

Within a month, Bulloch was in Liverpool with orders to create a Confederate Navy in England and find sailors to serve in it. He selected the firm of William C. Miller and Sons of Liverpool to build the first ship for the new navy: Florida, codenamed Oreto. Within weeks he contracted with Laird Brothers of Birkenhead to build a second, larger ship. Known first by her construction number, 290, she would later be christened Alabama. Both ships were built as commerce raiders to prey on Federal shipping.

After the departure of Florida and Alabama, Bulloch turned his attention to having the Lairds build ironclad warships, which became known as the Laird Rams. Such large warships quickly drew an equally large amount of attention from Federal officials who became alarmed that the ships would have their way with under-armed American vessels. The United States minister in London, Charles Francis Adams, penned a note to Lord John Russell, British foreign secretary, which ended ominously, “It would be superfluous of me to point out to your Lordship that this is war.” It was common knowledge that one of the Laird Rams had already conducted some preliminary trials.

The Sea King’s First Voyage

Lord Russell and the British cabinet might have been more alarmed had they known that the Lincoln administration had already discussed the possibility of having the United States Navy attack the rams at anchor in the Mersey, an act that might well have led to war with Great Britain. As far as the British could determine, the rams were not formally the property of the Confederate States, but it was unlikely that they were being built for the pasha of Egypt, as was being claimed. The British felt that they were being dragged into “neutral hostility” with the United States and ordered the rams to be seized. Royal Marines were placed on board both ships, and HMS Majestic, anchored nearby, formally detained the new vessels. The Confederates tacitly admitted their involvement when they asked Napoleon III of France to intervene on their behalf. Napoleon refused, and the Laird Rams ultimately were commissioned into the Royal Navy.

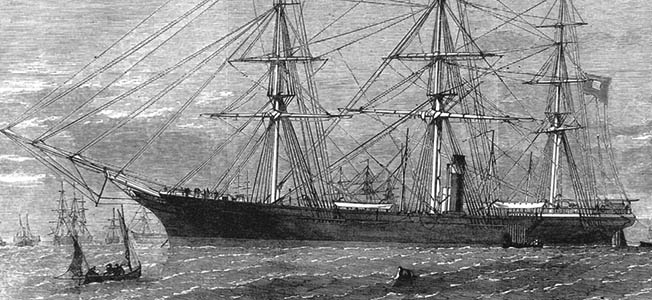

In the autumn of 1863 Bulloch visited Scotland in search of a replacement for Alabama, which had met her fate that June at the hands of the USS Kearsarge off the coast of Cherbourg, France. Bulloch spotted a fine-looking ship loading for her first voyage outbound to Bombay. Sea King was 220 feet long, with an 850-horsepower steam engine and a detachable hoisting propeller. The merchant ship had been built by Alexander Stephens and Sons of Glasgow and launched on the Clyde that August. Bulloch set about purchasing the ship for the Confederacy. He instructed Richard Wright, a Liverpool shipping merchant sympathetic to the Southern cause, to purchase the vessel as soon as she returned from Bombay. Eventually, Bulloch was able to report to Mallory that he had “the satisfaction to inform you of the purchase of a fine composite ship.”

Bulloch made a point of never setting foot on Sea King. All dealings were conducted in London, where the ship was moored. However, in Liverpool he did visit the iron-screw steamer Laurel, which he found to be well suited as a tender and blockade runner. A Liverpool shipping agent, Henry Lafone, took charge of the purchasing arrangements. Lieutenant John F. Ramsay of the Confederate Navy, a British subject who held a Board of Trade masters certificate, was chosen to command Laurel.

Sea King sailed from the Thames on October 5, 1864. At the same time, Laurel was made ready to sail to Havana, Cuba. Her passengers, taken out to the ship by tugboat, included several old hands from Alabama traveling under assumed names. Others came from the Sailors Home on the Liverpool waterfront, under the assumption they were to join a ship engaged in lucrative blockade running.

Late in the afternoon on October 14, Laurel reached Funchal on Madeira’s southern coast, the rendezvous port where she was to meet Sea King. Ramsay began coaling Laurel immediately. On board was Commander James Iredell Waddell, 42 years old, from Pittsboro, North Carolina, who would command the new raider. Waddell had been a mariner for more than 20 years, but Sea King would be his first command. He was a big man, over six feet tall, and walked with a limp, the result of a pistol ball lodged in his hip from a duel he had engaged in as a 17-year-old midshipman. Waddell was known to be stubborn to the point of obsession.

On the evening of October 17, Sea King reached Madeira. At daylight signals were exchanged with Laurel, which immediately began raising steam to leave the harbor. She soon caught up with Sea King, and Waddell ordered Ramsay to signal the other ship to lead the way to a tiny uninhabited island called Las Desertas. The two ships anchored and were lashed together to transfer stores and equipment. Charles E. Lining, the ship’s surgeon, described Sea King as “a splendid roomy looking ship,” although he was concerned that “there were only seven rooms, while we have ten commissioned officers.”

The good first impression did not last long. It took sailors nearly 36 hours of hard labor, working through the night, to transfer all the supplies and six heavy cannons from Laurel to Sea King. One three-ton cannon slipped while being winched aboard, crushing part of a bulwark. The guns remained on deck, waiting to be mounted on carriages while gun ports were cut into the ship’s side. To make matters worse, there was only one experienced carpenter between the two crews.

Waddell was well aware that he would have to start the cruise shorthanded. Ideally, he needed a crew of about 150 sailors, more than had come out on both ships. He was confident he could convince most of the British seamen to join him. He was mistaken. With the majority of the stores stowed away, the men assembled on Sea King’s quarterdeck. Waddell, dressed in his Confederate uniform, addressed them. He told them the ship now belonged to the Confederate Navy; she was a cruiser and would soon set out to destroy merchant vessels registered to the Union. He urged them to join him. Those who signed on, Waddell said, would receive two months’ wages and a signing bonus of 10 pounds each. His offer was met with stony silence. One or two of the men said they were not about to join a Confederate raider or break the terms of the British Foreign Enlistment Act. They had thought they were joining a blockade runner, not a warship.

The CSS Shenandoah

Sea King’s erstwhile captain, Peter Corbett, appealed to the men to join the Confederates. Waddell offered to increase the monthly wages and signing bounty to 15 pounds, but to little avail. Only 22 of the 55 sailors joined up. This meant that the ship had 24 officers and petty officers and just 22 seamen. That evening, Captains Ramsay and Corbett and those sailors who had refused to sign on to Sea King climbed back aboard Laurel. The two ships were unlashed and Laurel steamed away. As she did so, the Confederate ensign was unfurled over Sea King, now renamed CSS Shenandoah.

The crew set about making Shenandoah ready for sea. There were barely enough men, even with the officers taking on manual tasks, to man the engine room and sails. Worse yet, it was discovered that the fighting bolts and gun tackles needed to mount the main armament were missing. Without them, the guns could not be fired. The ship, except for small arms—Enfield rifles, pistols, and cutlasses—was defenseless.

Waddell assembled his officers aft and laid out the position to them: The crew was at less than half strength, and Shenandoah could not fight without fully mounted cannons. They had two options—head for the Canary Islands and hope to recruit more men, or head for the open seas and try to carry out their mission and acquire the missing tackles and more crewmen some other way. Lieutenant William Whittle, Shenandoah’s 24-year-old executive officer, argued that going to port so early might invite disaster; after all, Florida had been taken in a neutral port. Waddell’s orders from Bulloch targeted “the utter destruction of the New England whaling fleet” in the northern Pacific. Waddell doubted that they would ever reach the Pacific, but his officers were keen to press on. He went along with the majority view, and Shenandoah sailed south toward the Cape of Good Hope.

The weather was kind on the initial leg of the journey, enabling Shenandoah’s small crew to complete much preparatory work. A few days later, however, they ran into heavy rain and squalls. The decks leaked, as did, more alarmingly, some of the hull seams. The ship’s carpenter was unable to fashion the gun blocks. With only small arms and a large measure of bluff, Waddell hoped to capture a vessel that could supply the missing blocks and additional crew members.

At dawn on October 27 the call was heard, “Sail ho!” The deck officer at the time was James Bulloch’s half-brother, Irvine Bulloch, who had served on Alabama. Bulloch shouted orders to give chase. By 4 pm they were close enough for the lookout to identify the vessel as American due to her rigging and long mastheads. By then Shenandoah’s own rigging was crowded by crewmen straining for a view of the target ship. An hour later they could see a Union Jack flying, but this was an old trick used against raiders. As Shenandoah drew closer, the men fired a blank cartridge from one of the ship’s small guns. It had the desired effect of forcing the other ship to heave to. The bark Mogul was indeed American-built, but her papers indicated that she was sailing as a British cargo ship. Waddell had no choice but to let her pass. Once she reached port, a warning undoubtedly would go out to other ships that a new Confederate raider was in the area.

The following day crewmen spotted more sails. However, by dark they had still not closed with the new vessel. During the night they maintained the same course. At dawn on October 29, she was still in sight and they had narrowed the gap. The ship was flying Old Glory. It was the bark Alina out of Searsport, Maine, carrying a load of railroad iron. The crew was taken off to Shenandoah and everything of use transferred as well. Then a hole was knocked in the bottom and Alina soon sank. Lieutenant Whittle judged the sight “good and awful.” Alina was later valued at $95,000, but, more importantly, Shenandoah now had enough ropes and tackles to make her main guns serviceable. The 12 captured crewmen were invited to sign on with Shenandoah. Six agreed, including two Frenchmen and four Dutchmen. On the same day Alina was sunk, the British consul in Tenerife arrested Peter Corbett for violating the Foreign Enlistment Act.

Taking Ship After Ship

Six days later, west of the Cape Verde Islands, Shenandoah’s lookouts spotted more sails. The next morning a boarding party identified the ship as Charter Oak, out of Boston on her way to San Francisco with nine people on board, including the captain’s wife, her sister, and son. The ship supplied more booty for Shenandoah, including 2,000 pounds of much-needed canned goods. Waddell, hoping the smoke might attract assistance and another possible capture, had his seamen slosh turpentine onto Charter Oak’s deck and set her ablaze.

Six days later, west of the Cape Verde Islands, Shenandoah’s lookouts spotted more sails. The next morning a boarding party identified the ship as Charter Oak, out of Boston on her way to San Francisco with nine people on board, including the captain’s wife, her sister, and son. The ship supplied more booty for Shenandoah, including 2,000 pounds of much-needed canned goods. Waddell, hoping the smoke might attract assistance and another possible capture, had his seamen slosh turpentine onto Charter Oak’s deck and set her ablaze.

On November 7 Shenandoah overtook the Boston-based bark D.G. Godfrey, bound for Valparaiso, Chile, with a cargo of lumber and barrels of salted meat. She too was set on fire. Of the 10 sailors aboard the captured ship, six agreed to join Shenandoah, including a black steward, John Williams. The others were transferred, along with Shenadoah’s other captives, onto a passing Danish ship, Anna Jane, whose captain agreed to take them with him to Rio de Janeiro after Waddell gave him two extra barrels of food and a chronometer taken off Alina.

Over the next month the Confederate raider took still more ships. The brig Susan, carrying Welsh coal to Brazil, was barely seaworthy, and Waddell had her scuttled. Three more British sailors joined Shenandoah’s crew. Another ship bearing coal to Brazil, Kate Prince, was stopped three days later. She was clearly an American vessel, but Waddell concluded that her cargo was British. He decided to ransom his prize, allowing her to continue her journey after her captain agreed to take the remaining prisoners off Shenandoah and sign a $40,000 bond payable after the war.

On November 12, lookouts spotted Adelaide, a bark flying the Argentine flag. Adelaide’s captain, James P. Williams, was clearly American. He admitted that the ship was bound from Baltimore to Brazil with a load of flour belonging to a New York merchant. After an extensive search, the ship was bonded for $24,000 and released, Waddell sparing the ship because Williams convinced his captors that he was secretly a Confederate sympathizer.

The next day Shenandoah gave chase to another ship, Lizzie M. Stacey, a Yankee schooner out of Boston bound for Honolulu. Eight men were taken off—four joined the Confederate crew—and she was set on fire. Two days later, Shenandoah crossed the equator, conducting the traditional ceremony of a kangaroo court for first-timers presided over by old King Neptune “with an immense harpoon in his hand and a chafing mat for a hat.” With the additional sailors, daily life on board Shenandoah was now much easier for all involved.

Melbourne, Australia

By December Shenandoah had changed course to the southeast, making 10 knots an hour on the trade winds while heading toward the Cape of Good Hope. On December 4 the raider came across Dea del Mare, an Italian merchantman built in the United States. Later that day another ship was spotted flying the Stars and Stripes, Edward, a whaler out of New Bedford, Massachusetts. The crewmen were busy cutting up and hoisting a whale carcass and did not even notice the Confederates until they were within cannon range. “The odor from a whaling ship is terribly offensive,” Waddell noted. He stripped the ship of anything useful and burned her. With 26 new prisoners, Shenandoah once again was overcrowded, so Waddell diverted to the island of Tristan de Cunha, a tiny British protectorate. There Waddell negotiated with the island’s unofficial governor, Peter Green, and paroled the prisoners with six weeks’ worth of rations, including four barrels of beef, four barrels of pork, a cask of flour, and 1,680 pounds of bread. Three weeks after Shenandoah left, USS Iroquois called at the island looking for the Confederate ship.

Waddell headed for Melbourne, Australia, although once again he did not share his destination with his fellow officers. With better winds and to save coal, he ordered the propeller hoisted from the water and full sails put on. The propeller’s brass-band engine coupling was found to be cracked. Temporary repairs were made, but it really needed replacing in a proper shipyard. The closest was at Cape Town, but Waddell decided that with good winds he would continue to Melbourne.

On December 16 they rounded the Cape of Good Hope ahead of schedule. Shenandoah was soon running in heavy seas. Discord among the exhausted crewmen was often settled with fistfights. The relationship between Whittle and Waddell was similarly strained, with Waddell peremptorily countermanding Whittle’s orders without telling him. Waddell also ordered two lieutenants, Dabney Scales and Francis Chew, replaced for lack of seamanship. Chew in particular was something of a jinx: if anything went wrong, it was on his watch. Whittle worried that the men’s esprit de corps would be destroyed by “such arbitrary and unwarrantable acts of authority,” but he later conceded that Chew was incompetent.

The end of December approached with calmer winds. On December 29, Shenandoah caught up with the bark Delphine, out of Bangor, Maine, on her way to Burma to pick up a cargo of rice. Waddell’s men boarded and burned Delphine, whose value was set at $25,000. Of the crew of 15, six decided to join the Confederates. Delphine’s captain, William Nichols, had his wife, Lillias, sailing with him. Waddell found the 26-year-old woman “tall, finely proportioned and possessing a will and voice of her own.” She became his unlikely confidante.

Shenandoah stopped at St. Paul Island, hoping to find a Yankee whale ship in port, but there were none in the vicinity. After laying in fresh provisions of eggs and chickens, the raiders continued on their way. On January 17 they stopped Nimrod, an American-built ship owned by the British. Leaving the ship unmolested, Waddell’s crew found the air pump valve on Shenandoah’s steam engine broken and further damage to the propeller. Approaching Melbourne, the raiders were relieved to find no Federal ships in port. News of their arrival soon got around, and the Confederates were met by a flotilla of small craft, loaded with passengers eager to catch sight of the notorious Rebel ship.

A 23-Day Delay

Shenandoah’s crew was happy to be in Australia during the summer. Waddell shared their enthusiasm, but was aware that British and American authorities would not be pleased. He contacted the governor of Victoria to ask permission to make repairs and temporarily store his ship. The American consul in Melbourne, William Blanchard, formally interviewed the prisoners on Shenandoah, one of whom told him the ship had originally been the British-registered Sea King. Blanchard hurried off letters to U.S. Minister Charles Francis Adams in London and to the American consul in Hong Kong, urging the latter to send a naval cruiser to Melbourne to attack the Rebel ship.

On January 26 Waddell received formal permission for Shenandoah to remain in port for repairs. He granted much-needed shore leave to the crew and contracted with the local marine firm of Langland Brothers & Compan to carry out the repairs, which were more extensive than first anticipated. The Williamstown dry dock, a government facility, was leased to Langland Brothers for the repairs.

It would be 23 days before Shenandoah was ready to leave Melbourne, days of verbal battles between pro-Union and pro-Confederate sympathisers. Shenandoah’s officers were entertained by Australian admirers, while rumors got around that Union agents were planning to blow up the ship. Blanchard, stirring up trouble wherever he could, offered crew members $100 to desert. Eighteen accepted the offer, including Williams, the black cook. Another deserter told Blanchard that Williams’s job had been taken over by a locally recruited cook called Charley, a young Scotsman known to the Melbourne police as James Davidson. Blanchard complained to Australian Governor Sir Charles Darling that the Foreign Enlistment Act was being broken. The governor handed the matter to the local police, who issued a warrant for Davidson’s arrest.

The police arrived at Shenandoah to carry out the warrant, but deck officer Lieutenant John Grimball refused to allow them access to the ship. The police put a cordon around the gangplank. The confrontation resumed the next day, and Waddell similarly refused permission for the police to come aboard, stating that the warship was the sovereign territory of the Confederate States of America. Upon learning of the rebuff, Darling rescinded permission for Shenandoah to remain in port. Later that day a large body of police, supported by soldiers, arrived at the dock to detain the ship. Waddell offered to surrender, but pointed out that he and his men would thereby become prisoners of the British government. Darling, weary of the entire controversy, ordered Shenandoah released. At high tide on February 15 the ship was towed out of dry dock and loaded with coal and supplies. Three days later she left Melbourne. By 11:45 am she was safely out of Hobson’s Bay heading for the open sea. Forty-two stowaways came out of hiding and joined the crew.

“Not The Happy Ship She Might Be”

Two days later Shenandoah was 500 miles northwest of New Zealand. Waddell had not confided to his officers their destination but ordered a northerly course into stormy seas. Waddell told Chew that he was frustrated at finding no Yankee whalers off New Zealand, but that their ultimate target was the American polar fleet in the North Pacific. Chew promptly told the other officers. Whittle, for one, was dumbfounded to hear it. Shenandoah, he confided in his diary, was “not the happy ship she might be.”

Two days later Shenandoah was 500 miles northwest of New Zealand. Waddell had not confided to his officers their destination but ordered a northerly course into stormy seas. Waddell told Chew that he was frustrated at finding no Yankee whalers off New Zealand, but that their ultimate target was the American polar fleet in the North Pacific. Chew promptly told the other officers. Whittle, for one, was dumbfounded to hear it. Shenandoah, he confided in his diary, was “not the happy ship she might be.”

On March 25 they crossed the equator for the second time. No Union ships were found in the islands of the South Pacific. Four days later they heard from the captain of Pfeil, a schooner from the Sandwich Islands, that American whalers were at Ascension Island. Shenandoah set off in hot pursuit. As they approached the island, lookouts could see sailing craft in the harbor. One was flying Hawaiian colors, three others the Stars and Stripes. The whalers, thinking the approaching ship must be a British survey vessel in need of a pilot, sent out English pilot Thomas Harrocke, who agreed to take Shenandoah through the narrow entrance for 30 dollars. Waddell warned Harrocke that he would be shot at the first sign of a trick.

Once through the harbor entrance, Shenandoah dropped anchor, blocking egress to the whalers, and lowered four boats with boarding parties. A signal gun was fired and the Confederate flag was raised to replace the British one they had been flying. The raiders quickly seized Edward Carey of San Francisco, Pearl from New London, Hector of New Bedford, and Harvest of Honolulu, the four ships’ cargoes being valued at $117,759. All four were looted and burned after Waddell allowed local natives to carry away anything they wanted. Waddell then granted his men five days’ liberty on the island, one of which was April 9, the day that Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox.

On April 13 Shenandoah steamed away from Ascension, setting a north-northwest course. They lifted the propeller the next day, relying on sails alone, and with a steady wind made 210 miles in one day. Heading toward Arctic waters, the ship sailed the eastern coast of China, encountering torrential rain, heavy seas, and much colder weather. The crew went back to grumbling, and those who had signed on for six months’ duty now wanted off. By May 20 they were approaching the coast of Siberia and ice was beginning to appear, at first in small bits but soon in large icebergs they had to steer around.

Passing Siberia

On the morning of May 27, lookouts spotted a ship flying the Stars and Stripes on the other side of an ice flow. She was Abigail, out of New Bedford, Massachusetts. The raiders boarded the ship, took off 36 prisoners and other valuables, and set her ablaze. Much to Waddell’s frustration, Abigail was the only prize in the icy waters off eastern Siberia. Ice was now 15 to 30 feet thick, blocking further progress to the north. Shenandoah was battered by winds and rain that turned to snow and froze the rigging. Extra rations of grog and hot coffee were dispensed to the crew to help them keep warm.

By the middle of June, Shenandoah was far enough north to be in a boreal realm where the sun was above the horizon 18 hours a day. Passing Cape Navarin, Siberia, the raiders moved through water increasingly littered with whale meat and blubber. Between June 22 and 28, Shenandoah enjoyed her most successful period, capturing 24 ships, 10 on June 28 alone. On that one fatal day, more than $500,000 worth of Federal shipping was destroyed or bonded, and the price of lamp oil consequently would skyrocket along the Eastern Seaboard for nearly a year. One of the captives, Captain Jonathan Hawes of the whaler Milo, told Waddell that the war was over. Waddell dismissed the story as a ruse, but allowed Hawes to go on his way after Hawes agreed to take the other prisoners on to San Francisco and sign a bond for $40,000.

The next day the raider turned south, skirting the Aleutian Islands and steering southeast. By July 5 Shenandoah had left the Arctic. Waddell was in a dilemma over what to do next. The Arctic mission complete, he considered an attack on San Francisco, but dismissed the idea as impractical. However, as they neared the coast of California, Waddell contemplated attacking that state’s treasure-laden steamers, which routinely voyaged between San Francisco and New York via Cape Horn. On August 2 they met the British bark Barracouta, 13 days out of San Francisco bound for Liverpool. When Irvine Bulloch led a boarding party onto the ship, he asked the British captain for news regarding the war. “What war?” the captain replied. “The war between the United States and the Confederate States,” Bulloch said. The astonished Englishman told Bulloch that the war had ended in April and that Federal warships were combing the seas for the now-outlawed Rebel vessel.

After consulting with the crew, Waddell decided to decommission the ship’s armament. Her guns were dismounted and placed in the hold; gun ports were sealed. Since their government apparently had ceased to function, some of Shenandoah’s officers felt they should go to the nearest American-held port and surrender. Most were against this notion, worrying that they would be treated as pirates and possibly hanged. They decided to sail for the nearest British port, Sydney, Australia, and abandon the ship to Her Majesty’s authorities. A course was set for Sydney. The next day, however, Waddell changed his mind, deciding to head for Liverpool, 17,000 miles away, where he believed they would receive better treatment.

Looping south around the coast of South America, Shenandoah had to conduct much of the voyage under sail, since coal supplies were dangerously low. Gale-force winds and foul weather beset the ship as she rounded Cape Horn. South of the Falkland Islands, Shenandoah encountered icebergs “castellated and resembling fortifications with sentinels on guard,” Waddell noted. On October 11 they crossed the equator for the fourth time in the past year.

An Ignoble End

On November 5 Shenandoah finally reached Liverpool but had to wait for favorable tides to enter the port the next day. The raiders had sailed 23,000 miles from the Aleutian Islands to the Irish Sea without sighting land for 122 days. In so doing, Shenandoah became the only Confederate ship to circumnavigate the globe. The next day she arrived off Birkenhead, dropping anchor behind HMS Donegal and formally surrendering to Captain James Paynter at 10 am. During the course of her remarkable career, Shenandoah had sailed 58,000 miles and taken 38 ships with prizes valued at $1,172,223.

Ultimately, the American government decided not to bring piracy charges against Shenandoah or her crew. Eventually, the ship was sold at auction to the sultan of Zanzibar. Renamed Majidi, she was reduced to carrying freight around the Indian Ocean. In 1879 she tore out her bottom on a reef in the Mozambique Channel and sank, an ignoble end for the proud Confederate raider. The British government later paid $6.5 million in damages to the United States for losses incurred during Shenandoah’s wartime—and post-wartime—career.

Great account.

At life at sea and at war.

The British government was crazy to pay compensation.

Probably started the American junkie style fix on litigation

Will read plenty more