By Joshua Shepherd

For William Henry Harrison, the letter he received on October 12, 1811, constituted not only official orders, but something of a personal vindication as well. As the governor of Indian Territory, Harrison had been warning the War Department for more than five years of the dangerous threat posed by the Shawnee tribal leader Tecumseh and his brother, Tenskwatawa, called the Prophet. Although President James Madison had repeatedly urged Harrison to continue showing forbearance in dealing with the increasing number of border killings, Secretary of War William Eustis, on his own initiative, had issued a new set of instructions that granted the governor wide latitude in dealing with the Prophet and his followers encamped on the Tippecanoe River. “You will approach and order him to disperse,” wrote Eustis. “If he neglects or refuses to disperse he will be attacked and compelled to it by the force under your command.” Harrison had been anxiously preparing for such a move against the Prophet and quickly reported to Eustis that “nothing now remains but to chastise him and he shall certainly get it.”

Harrison’s repugnance for agitators came naturally. A scion of Virginia gentry, he was born on February 9, 1773, at the magnificent manor house of Berkeley Plantation on the James River. Commissioned an ensign in the United States Army in 1791, Harrison eventually served as an aide de camp to Maj. Gen. “Mad Anthony” Wayne. In that capacity Harrison saw action at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794 and was present for treaty negotiations at Fort Greenville the following summer. The Treaty of Greenville, which secured to the United States the southern two-thirds of Ohio, pacified the belligerent tribes of the Northwest Territory after decades of continuous warfare, but likewise served as the genesis for future conflict.

Opposition to the Treaty of Greenville

From the outset, the peace settlement was not without its detractors. Opposition to the treaty was headed by Tecumseh, who had boycotted the negotiations. Although not a chief in any official capacity, Tecumseh, just 27 years old in 1795, quickly gathered a following of disaffected tribesmen who were determined to resist further American expansion, and the group established its own independent village outside the aegis of tribal authorities.

Ironically, the treaty itself served to buttress the salient point of Tecumseh’s resistance doctrine. Although it was customary to form agreements with a handful of tribes on the basis of territorial ownership, at Greenville the United States had succeeded in treating with more than 10 separate Indian nations at once, and virtually the entire native population of the Old Northwest had been represented. Although the provisions of the treaty could therefore be considered wholly legitimate, a dangerous precedent had been established by such tacit recognition of collective tribal ownership. Tecumseh insisted that the land was held in common by all the tribes and any further American attempts at territorial acquisition should be handled accordingly.

This concept was at loggerheads with official American policy. During the administration of President Thomas Jefferson, government officials increasingly implemented an aggressive system of territorial expansion aimed at extinguishing tribal claims. Jefferson consequently encouraged federal trading posts to extend unrestrained credit to the tribesmen and thereby foster a cycle of indebtedness among the natives. “When these debts get beyond what individuals can pay,” observed Jefferson, “they become willing to lop them off by a cession of lands.”

The point man in implementing Jefferson’s policies was Harrison, who had been appointed governor of the newly created Indiana Territory on May 13, 1800. In addition to his duties as governor, Harrison assumed the roles of superintendent of Indian affairs and treaty commissioner; at the latter task he quickly set to work and proved immensely successful. Between 1803 and 1805, Harrison concluded some half-dozen treaties with individual tribes and secured nearly 30 million acres for the United States.

The Rise of Native Nationalism

The incessant prosecution of land acquisition treaties did not go unnoticed by Tecumseh and his recalcitrant band, which had been inflamed by the steady depletion of Indian territory. In the summer of 1805, Tecumseh established a village beneath the very walls of old Fort Greenville in a defiant gesture to American authorities. Tecumseh’s Greenville village grew steadily over the succeeding three years as he continued to attract natives disaffected by the appeasement policies of elder tribal leaders.

Tecumseh actively sought to blur tribal distinctions and promote a pan-Indian nationalism, and his efforts to attract a wider following were greatly aided by the activities of his eccentric, one-eyed brother, Tenskwatawa. Regarded as little more than a drunken miscreant in his youth, Tenskwatawa had supposedly fallen into a trance in 1805 and underwent a radical transformation. Assuming the mantle of a Shawnee tribal prophet, he began preaching an ascetic brand of native witchcraft, condemning liquor, intermarriage, and the adoption of American-style agriculture.

The Prophet quickly secured a broad-based cult following and tested the bounds of his power in the spring of 1806 by launching a virtual reign of terror with the aim of awing the natives into submission. Several Indians, including a Christian convert and an aged Delaware chief, were accused of witchcraft and burnt at the stake on the Prophet’s orders. The fanatic dedication of the Prophet’s followers alarmed both Harrison and older tribal leaders. Harrison dispatched an angry reprimand to the Delaware for the part they played in the executions and contemptuously pointed out the fact that no miracles had been performed by “this pretended prophet who dares to speak in the name of the Great Creator.” An exasperated Harrison reported to the secretary of war in July of 1807 that war belts had been circulating through the tribes, and he hinted at the broader implications posed by potential hostilities. “I really fear,” wrote Harrison, “that this said Prophet is an engine set to work by the British for some bad purpose.”

Ever since the close of the Revolution, anger over British intrigue had enraged the frontier population. These suspicions were inflamed anew subsequent to the Chesapeake affair in June of 1807 and resulted in a heightened sense of impending conflict with Great Britain. Harrison warned the territorial assembly that they should be prepared for “the contest which is likely to ensue, for who does not know that the tomahawk and scalping knife of the savage are always employed as the instruments of British vengeance.” Although the British had as yet offered no overt assistance to Tecumseh and the Prophet, British subjects circulated south of the Great Lakes with impunity and Sir James Craig, the governor of Upper Canada, encouraged his agents to establish contact with the Prophet and privately impress upon the natives “with delicacy and caution that England expects their aid in the event of war.”

“It is Our Intention to Live in Peace”

By the spring of 1808 the suspicions of American authorities had been so aroused by his activities that Tecumseh sought a more isolated locale for his village and settled at the confluence of the Wabash and Tippecanoe Rivers in Indiana Territory. From his secluded base on the Wabash, Tecumseh began laying the groundwork of an Indian confederacy that would stretch from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico and would constitute the most ambitious effort of native resistance ever attempted on the continent.

Harrison had encouraged the disbandment of the village at Greenville and was pleased to receive a letter from the Prophet in July 1808 assuring him of the Tippecanoe settlement’s pacific intent. The Prophet then met personally with Harrison, assuring the governor that “it is our intention to live in peace with our father and his people forever.” In surprising testament to Tenskwatawa’s hypnotic appeal, the governor was completely taken in by the deception. Harrison reported to the secretary of war that “the influence which the Prophet has acquired will prove rather advantageous than otherwise.”

The rapprochement would prove to be short-lived. By the spring of 1809, Indians as far away as Missouri admitted that they had been courted to war against the frontiersmen, and Indian agent William Wells, convinced that the Prophet was in communication with British operatives, reported that Tenskwatawa had requested neighboring tribes to “receive the tomahawk from him and destroy all the white people at Vincennes.” At last convinced of the Prophet’s true motives, Harrison confessed that “my suspicions of his guilt have been rather strengthened than diminished.”

The final breach came in the autumn of 1809. On orders from Washington, Harrison concluded yet another treaty at Fort Wayne on September 30. Meeting with delegates from the Miami, Delaware, Kickapoo, and Potawatomi tribes, Harrison acquired some three million acres lying north of Vincennes. The loss of this tract, referred to as the New Purchase, infuriated the Indians at Tippecanoe and contributed to a rapid destabilization of the frontier.

“Do Not Think That the Red Coats can Protect You”

Hostilities escalated with the destruction of settlers’ property as well as a handful of mysterious murders. Harrison opened an angry correspondence with the Prophet and offered forgiveness if the natives would be willing to repent. Harrison added an ominous threat that portended future trouble. “Do not think that the red coats can protect you,” he warned, “they are not able to protect themselves.” In response to Harrison’s concerns, the Indians made arrangements for another conference, albeit not with the Prophet but with Tecumseh.

Although he had previously assumed a relatively inconspicuous role in comparison with his more flamboyant brother, Tecumseh proved to be the calculating brains of the duo. He had honed his skills as a masterful orator during his extensive travels to promote Indian unification. At the age of 42, Tecumseh was at the apogee of his power and cut an imposing figure. “Perhaps one of the finest looking men I ever saw,” thought one Army officer, “about six feet high, straight, with large fine features and altogether a daring bold-looking fellow.”

The council with the governor was set to open at Harrison’s Vincennes estate on August 12, 1810, and resulted in a dramatic confrontation between their respective peoples’ chief protagonists. From the moment it started, the council was an uneasy affair. Tecumseh, who had arrived at Vincennes with 80 warriors, made it clear that he was ill disposed for conciliation. In a lengthy harangue, he laid out his objections to American expansion, and although he insisted that he had no intention of going to war, he likewise avowed that the natives were “determined to make a stand, where they were.” Tempers flared amid mutual accusations, and fighting almost erupted on the spot. Ultimately, Tecumseh refused to acknowledge the validity of the New Purchase, which Harrison was anxious to survey, and insisted that the governor was to blame for the recent troubles. “You try to force the red people to do some injury,” he said, “but it is you that is pushing them to mischief.”

Harrison was convinced that an armed confrontation was all but inevitable and requested instructions from Secretary of War Eustis regarding the disposition of troops, the survey of the New Purchase, and the construction of military installations to secure it. He likewise reported that it was Tecumseh, not the Prophet, who was “the Moses of the family” and therefore to be regarded as the real leader of the hostiles at Tippecanoe. “A bold, active, sensible man,” wrote Harrison, “daring in the extreme and capable of any undertaking.”

Eustis replied that given the precarious nature of Anglo-American relations, it was presently considered not expedient to run the boundary of the New Purchase. As Indian depredations and border tensions grew more intense, Harrison was at a loss how to proceed. “Our backwoods men are not of a disposition to content themselves with land of an inferior quality,” he wrote Eustis, “when they see in their immediate neighborhood the finest country as to soil in the world occupied by a few wretched savages.”

An Opportunity to Destroy Tecumseh’s Confederacy

Events rapidly headed toward confrontation the following year. Indian depredations continued from Indiana to Missouri, and on June 24, 1811, Harrison penned a stern rebuke to Tecumseh. “This is the third year that all the white people have been alarmed at your proceedings,” wrote Harrison. “You threaten us with war, you invite all the tribes to the north and west of you to join against us.” Tecumseh replied that he would visit Harrison and “wash away all these bad stories.” Again meeting the governor in Vincennes, Tecumseh adopted a conciliatory tone, and a bemused Harrison wrote that “one would have supposed that he came here for the purpose of complimenting me.” Tecumseh continued to profess peaceful intentions and promised to consult with Harrison in the spring after he had made a visit to the southern tribes. Harrison remained unconvinced and felt certain that Tecumseh’s purpose on the trip was “to excite the Southern Indians against us.”

By informing Harrison of his trip south, Tecumseh unwittingly committed a grave strategic blunder. Harrison immediately informed Eustis that “his absence affords a most favorable opportunity for breaking up his Confederacy. I have expectation of being able to accomplish it without a recourse to actual hostility.” Harrison’s plan, as outlined to Eustis, was to advance to the northern boundary of the New Purchase, construct a fort, and thereby intimidate surrounding tribes to isolate Tenskwatawa and force the breakup of Prophetstown, as the village had come to be known. Although Harrison considered a peaceful resolution still possible, he nonetheless insisted that “to ensure success some military force must be brought to view.” Bringing such a military force to view in the vicinity of Tippecanoe could very well invite attack, but Harrison was certain that Tecumseh’s absence afforded a unique opportunity in a narrow window of time. “The Prophet is imprudent and audacious,” wrote Harrison, “but is deficient in judgment talent and firmness.”

Because President Madison spent much of the summer of 1811 at his home in Virginia, Eustis was forced to navigate the situation largely on his own. Ultimately, he authorized an expedition. “It is presumed,” wrote Eustis, “no objection or difficulty will arise from crossing the boundary of the territory, if circumstances should require it.” The ambiguous nature of the orders, which granted Harrison wide latitude in their interpretation, virtually guaranteed an armed confrontation.

A Mix of Regulars and Militia

Harrison quickly began organizing an armed force and ordered the 4th Infantry Regiment, which Eustis had stationed in Newport, Kentucky, to advance to Vincennes. The greater part of Harrison’s force was composed of Indiana militia, and the regulars naturally viewed them with suspicion. Private Adam Walker thought the backwoodsmen sported “a savage appearance,” garbed in “a short frock of deer skin, a belt around their bodies with a tomahawk and a scalping knife.” Walker nonetheless grudgingly admitted that “the Militia from Kentucky and a few companies from Indiana were decent soldiers.” Members of the Kentucky contingent to which Walker alluded, 60 dragoons under the command of Major Joseph Hamilton Daviess, had purchased their own sabers and horse pistols and were itching for a fight. Daviess was an enthusiastic, if eccentric, southern gentleman whose energies and personal ambition would prove a mixed blessing to the expedition. A United States attorney who had sought unsuccessfully to prosecute Aaron Burr, Daviess had a knack for making a spectacle of himself and had once worn a conspicuous red shirt to the capital “to make sure the Washingtonians knew he was in town.”

Alarmed by the sudden display of force in Vincennes, the Prophet dispatched emissaries to calm Harrison, but the effort degenerated into a diplomatic farce. The Indian party inexplicably stole horses from a nearby settlement and an Army contractor, then fled north. Harrison ordered a pursuit, and although the horses were recovered, the Americans were fired on in a brief confrontation.

Two Casualties Before Hostilities

Finally armed with a provocation that justified a demonstration against Tippecanoe, the governor set his expedition into motion on the south bank of the Wabash on September 26. Determined to avoid an ambush, Harrison employed a marching formation he had learned under Anthony Wayne in the 1790s. A screen of scouts fanned out in advance of the main force, whose van, flanks, and rear were covered by dragoons and mounted riflemen. The main body of infantry, divided into two columns on opposite sides of the trail, guarded the supply wagons and beef herd.

By October 3, the army had advanced 65 miles. Harrison halted the march to begin construction of the installation authorized by Eustis. Fort Harrison, as the post was christened, took the better part of a month to complete, and the expedition’s progress was further stalled by the incompetent performance of Army contractors. Their axes were discovered to be of inferior quality, and flour was not forwarded in a timely manner, necessitating short rations for the men.

Increasingly, there was little doubt as to the Prophet’s true intentions. A sentry was killed and a supply boat carrying corn was attacked four miles south of Fort Harrison with the loss of one man. On October 29, Harrison again put his men back in motion and sent out a party of peaceful Delawares to treat with the Prophet, who refused to meet with the delegation. Two days into the march, the men constructed a fortified baggage depot, Fort Boyd, before crossing to the north bank of the Wabash to make the final approach to Tippecanoe. On November 6, the force was within five miles of the village and began seeing Indians.

Interpreters were thrown out to open parlay with the natives but, reported Harrison, the Prophet’s warriors would “return no answer to the invitations but continued to insult our people by their gestures.” Concerned that his men might be ambushed, Harrison closed the last few miles slowly and kept up constant patrols with his mounted riflemen, who cautiously probed timberland and ravines before the rest of the expedition was allowed to pass.

A Last Chance for Peace

A mile and a half from the village, Harrison halted and began making plans to encamp. Daviess and a few other officers approached the governor and urged an immediate attack. Harrison declined, noting that his orders did not authorize him to attack if there was a reasonable chance that the Indians might peacefully disperse. A determined Daviess pointed to the hostile demeanor of the Indians already encountered. Harrison agreed, but again insisted that a preemptive attack exceeded his orders, and he wanted better intelligence regarding the terrain. Daviess insisted that he and his adjutant had already advanced to the edge of the village (he had actually only seen a few outlying lodges) and the Army could advance without fear of ambuscade. Harrison relented and made one final attempt at parlay. Toussaint Dubois, a Vincennes fur trader and Harrison’s chief of scouts, volunteered to advance under flag of truce and establish contact. Once again, the Indians continued to menace and insult Dubois, who raced back to the Army when he observed the Indians were attempting to cut him off.

Harrison determined to attack the village, but the Prophet at last sent out three chiefs to speak to the governor. The Indians assured Harrison of their peaceful intentions and suggested that a council be held the following morning. Harrison agreed but did not like the looks of the ground south of the village, which was an open prairie ill suited to defense; better ground was to be had north of Prophetstown. Tensions mounted as the troops approached the village. Unsure of Harrison’s intentions, 50 or 60 warriors rushed out of the camp and began preparing for battle. Harrison personally rode to the front and, through an interpreter, assured the villagers that he was only seeking wood and water for his men.

Making a Defensive Camp

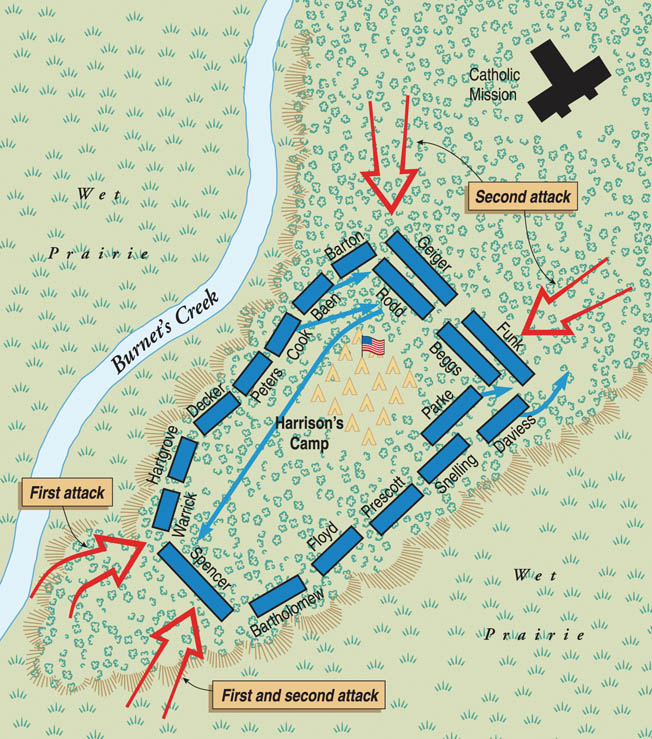

Harrison reported that “a mutual promise was again made for suspension of hostilities until we could have an interview on the following day.” The army filed off to the west and went into camp around 4 pm. The site selected was the best defensive position in the area, a small plateau that rose 10 to 20 feet from the surrounding countryside. The camp commanded open marshland, and to the west abutted a steep hillside that fell off into a creek bottom. The governor formed his troops into a hollow trapezoid to conform to the lay of the land and ordered the men to sleep on their arms. Harrison circled his camp with a sentinel screen, but he neglected to send out any scouts in the direction of the village. Due to the lack of good tools, the army likewise failed to erect breastworks.

Facing the creek, Harrison placed a battalion of Indiana militia under the command of Lt. Col. Luke Decker, as well as a battalion of the 4th under Captain William C. Baen. The left flank was occupied by mounted riflemen under the command of Major Samuel Wells. Harrison’s main line facing the direction of the village was held by a battalion of the 4th under Major George Floyd and a battalion of Indiana militia under Colonel Joseph Bartholomew. To cover his narrow right flank, Harrison placed Captain Spier Spencer’s Yellowjackets, an Indiana militia company so named for their homespun uniforms. All told, Harrison was able to muster about 1,000 effectives.

In the ranks of Captain Frederick Geiger’s militia at the northwest comer of the camp, friends Isaac Naylor and Joseph Warnock retired at 10 pm on opposite sides of a campfire. The previous night, Warnock had experienced a nightmare premonition that “foreboded something fatal to him.” “Having no confidence in dreams,” recalled Naylor, “I thought but little about the matter, although I observed that he never smiled afterwards.” Samuel Pfrimmer, one of Spencer’s Yellowjackets, remembered an old frontiersman named Bayard in his company. With a peaceful settlement in the offing for the following day, a number of soldiers were disappointed that they would see no action. The old man scoffed at such notions. “Sam, sleep with your moccasins on,” advised Bayard, “for them red devils are going to fight before day.”

Tecumseh’s Assault Begins

In the Tippecanoe village, the Indians were indeed making plans for an early morning assault. By “pronouncing some enchantment over a composition he had prepared,” the Prophet had convinced his warriors that victory was inevitable and assured them that by means of his spell “half the army was already dead and the other half bewildered.” Furthermore, he claimed, the Indians would be immune to gunfire; the Americans’ powder had turned to sand, and the warriors had nothing to do but “rush into camp and complete the work of destruction with the tomahawk.”

More experienced warriors knew better. Potawatomi chief Chaubenee, one of Tecumseh’s trusted lieutenants, urged greater caution in confronting Harrison. The Americans were like great trees, he said, but “when a great tree falls, it crushes many little ones.” The disappointed Chaubenee observed that “all of our chiefs were hot for battle. So I held my tongue.”

A drizzling rain fell that night, which served to both limit visibility and muffle the sounds about the camp; by the early morning hours the Army’s sentinels were bemoaning the cold and wet conditions. Out in front of Baen’s regulars at the northwest comer of the camp, Private William Brigham had been posted on guard duty since 3 am. Off to his left Brigham heard, and ignored, several whistles from fellow sentinel William Brown. A persistent Brown finally called out, “Look sharp!” although Brigham recalled that “no object could be discerned within three feet of me, and I could hear nothing except the rustling noise occasioned by the falling rain.” In a few moments, Brown showed up “much alarmed” and pleaded with Brigham to fire their weapons and head for camp. “You may depend on it,” assured a wide-eyed Brown, “there are Indians in the bushes.”

While the pair debated what to do, something landed in the brush nearby, which they supposed was an arrow, at which time, Brigham said, they were “both frightened and run in without firing.” At the same instant, Corporal Stephen Mars, a sentinel stationed in front of Geiger’s militia, saw Indians approaching through tall grass in his front and discharged his weapon, only to break for camp when a swarm of screaming warriors burst from cover. Mars had succeeded in alerting Harrison’s army, but was cut off and killed before reaching safety.

Confusion Among the Militia

In the ranks of Geiger’s militia, Naylor had awoken at 4 am from a dream of “firing guns and whistling balls,” caused, he thought, by the sound of the drizzling rain. He recalled that he was “engaged in making a calculation when I should arrive home” when he heard Mars’s gunshot. He briefly entertained the notion that a sentry had fired mistakenly when he heard another shot, followed by the haunting and unmistakable war cry of some 600 hostile tribesmen.

Their movements masked by the morning’s rainfall, the Indians had succeeded in closely approaching the Army’s sentinel screen before launching their attack. One sentry, Daniel Pettit, barely made it back to camp alive. Closely and furiously pursued by a single warrior, Pettit cocked his rifle on the run, then suddenly spun around and jammed the barrel of his rifle into his pursuer’s stomach. Both men fired simultaneously. The Indian fell with a shot through his body and narrowly missed Pettit, whose head scarf caught fire from the muzzle blast.

The initial Indian attack struck hard at the northwest corner of the camp. Captain Robert Barton’s regulars were caught unprepared. Awakened by an awful yell, Sergeant Montgomery Orr and Corporal David Thomas grabbed their muskets and scrambled to exit their tent. Thomas fell back onto his companion, who barked, “Thomas, for God’s sake don’t give back!” But as Orr recalled, “He made me no answer, for he was a dead man.”

When the attack had opened, a three-man detail was in the act of stoking the campfires, and their position was well lit to the onrushing natives. Confusion reigned, the men unsure if they should form in front or in rear of their tents. Barton ordered his men into line but reported later that “they were too much broken, and no regular line could be formed.” Fighting stubbornly in scattered groups, Barton’s regulars opened up a steady fire and maintained a tenuous hold on their position.

To Barton’s right, Geiger’s militia was overwhelmed by the ferocity of the attack and was on the verge of collapse. Joseph Warnock, who two nights earlier had experienced a premonition of death, was shot almost instantly. “He ran a few yards,” recalled Naylor, “and fell dead on the ground.” The Indians pressed their advantage and poured a deadly fire into the militia ranks, which were clearly illuminated by the campfires. One militiaman remembered the horror of the moment, as the Indians were charging “most furiously and shooting a great many rifle balls into our camp fires, throwing the live coals into the air three or four feet high.”

The Indians pressed to close quarters and shattered Geiger’s left. When the captain ran to retrieve an extra gun for one of his men, he discovered Indians rifling through his tent and drove them off. One of Barton’s regulars observed that the militia was in great confusion and so intermingled with the enemy that they could hardly be distinguished from the Indians. The natives exploited the breach, and, as Harrison later reported, caused “great injury to Barton’s Company.” In the ensuing melee, Baen was rushed by a tomahawk-wielding warrior and was “shockingly mangled.” The rest of the Army escaped the brunt of the initial onslaught and was able to form up quickly.

The men frantically doused the campfires. Harrison, who was in the act of putting on his boots when the attack erupted, immediately sought out reinforcements to bolster the threatened sector of his camp. He pulled two companies of the 4th Regiment out of line from the relatively secure western side of the camp and ordered them to reform obliquely behind Barton and Geiger.

Stiff American Resistance

For the Prophet’s warriors, the fight was not going as expected. While their leader sat in the rear and chanted incantations, his men were suffering heavy casualties in the face of unexpectedly stiff American resistance. Most of Harrison’s men were firing charges containing 12 buckshot, which proved devastatingly effective in the low-light conditions. Although Harrison thought the natives “manifested a ferocity uncommon even with them,” the Indians, for their part, were demoralized by facing such dogged resistance from the Americans.

One Miami warrior witnessed another Indian kill a soldier, kneel to pull his scalp, and then receive a severe wound on his posterior from the saber of a lone American officer. Four other Indians then rushed the officer and a desperate struggle ensued. Swinging his sword wildly, the American wounded three of his assailants and mortally wounded the fourth with a point-blank shot from his pistol that tore away all the flesh and muscles from the upper part of his arm. The officer was finally overpowered and killed, but, noted the Miami witness, he had proved himself “a stout warrior.”

Daviess’ Charge

Forty-five minutes into the fight, Daviess had yet to see any action and his blood was up. His troop of dragoons was positioned in a supporting role in the northeast comer of the camp, and the major grew impatient with inactivity. The Indians in Floyd’s front had found good cover behind some downed timber and were pouring a galling fire into the regulars. Daviess sought out Harrison and pleaded for his dragoons to be put to better use. Throwing up his arm in the direction of the enemy, he asked, “Will you permit me to dislodge those damned savages behind those logs?” Harrison demurred; a frustrated Daviess repeated the request, which was again refused.

Daviess stalked off but was determined not to be denied. He sent Harrison a third request to launch a counterattack, to which an exasperated Harrison replied: “Tell Major Daviess he has heard my opinion twice, that he shall have an honorable position before the battle is over. He may now use his discretion.” The message was all the impetuous Kentuckian needed. He gathered a picked force of 20 dismounted dragoons and led them in a mad dash for the enemy. Daviess, wearing a conspicuous white coat, pulled ahead of his men and made an inviting target. He was quickly hit, and falling, was heard to cry out, “I am a dead man!” His demoralized troopers fell back, but succeeded in carrying off their stricken commander. The charge he had insisted on making had accomplished nothing.

The American Counterattack

A full company of regulars under Captain Josiah Snelling then launched their own counterattack and succeeded in clearing the enemy from the downed timber. The Indians expanded their attack around the camp’s perimeter, probing for a weak spot, and found it on the Army’s right flank. Occupied by Spencer’s Yellowjackets, the flank was defended by 80 men spread out along a 75-yard front. Ensign John Tipton later recorded that the Indians opened up a continual fire that was particularly devastating to the company’s officers. A friend at his side had his jaw shot away, recalled Tipton. “He suffered great agony, but soon died.”

Lieutenants Richard McMahon and Thomas Berry were shot dead. Spencer received a wound to the head, encouraged his men to fight on, and then went down with a painful wound in both thighs. Two privates were detailed to remove the captain on a makeshift litter, but before they could reach the field hospital, another ball struck Spencer and passed lengthwise through his body, killing him instantly. Harrison rode up with his staff and drew the attention of Indian marksmen. His horse was hit in the head and another shot, said the governor, came “very near terminating my earthly career.”

Harrison found the Yellowjackets hard pressed but holding their own under the command of Tipton. Harrison ordered Tipton to “Hold your own, my brave boy,” and rode off to gather reinforcements. Harrison ordered two companies from the 4th and one company of Indiana militia to support the Yellowjackets. The men immediately executed a charge that, reported Harrison, put the Indians “to precipitate flight.” Fleeing in confusion, numbers of warriors were exposed in the open prairie southeast of camp, and Harrison prepared to deploy his dragoons to sweep the field.

However, no dragoons were available. On his own initiative, Wells had launched an attack on the left flank. Bolstering his militia with regulars and the dragoons, he succeeded in driving off the Indians, who were disinclined to continue the fight in approaching daylight. The dragoons, however, were unable to follow up on their victory as the Indians fled through a swamp impassable to the horses. Seeing their enemy driven from the field, Harrison’s battered troops unleashed a spontaneous shout of three huzzahs, and, just as quickly as it had begun, the battle was over.

No Quarter

In the frenetic moments after the horrific fighting, little quarter was offered the enemy. One warrior, isolated on the prairie, suddenly rose up from the tall grass and ran for cover in the woods to the east. A group of regulars fired at him and missed; an Indiana rifleman quickly sprinted a few yards into the clearing and killed him with one shot. Kentuckians then took his scalp, divided it among themselves and skewered the pieces on their ramrods. “Such was the fate of nearly all of the Indians found dead on the battle ground,” remembered Naylor, “and such was the disposition of their scalps.”

An Indiana militiaman searching the prairie discovered a wounded Potawatomi chief, nudged him with his foot, and was met with a plea of “Don’t kill me” in broken English. Several regulars came up and snapped their pieces at him, but all misfired. An officer rode up on horseback and, brandishing his saber, told the men that “he would show them how to kill Indians.” Harrison had been watching the scene unfold and dispatched a runner just in time with orders to take the Indian prisoner alive. His shattered knee and ankle were dressed by army surgeons, but the man adamantly declined amputation and likewise refused to give Harrison any information.

At 8:30 am, Captain Peter Funk went to see Daviess. The Kentuckian had received several balls in the stomach, and his wounds were pronounced mortal. In “great pain and consternation,” said Funk, Daviess expressed just one regret, “that he had military talents” but “was about to be cut down in the meridian of life without having an opportunity of displaying them for his own honor, and the good of his country.” Fearing that the Army would retreat and abandon him to the enemy, the delirious Daviess extracted a promise from Funk that he would not be left behind. Expiring soon thereafter, Daviess was buried between two trees, his grave camouflaged to prevent desecration by the Indians.

Aftermath of the Battle of Tippecanoe

Although they had severely mauled Harrison’s troops, the impact of the defeat proved devastating to the Prophet’s followers. As his disillusioned warriors returned to confront him, the Prophet, reported one witness, sat crestfallen, with his head tucked between his knees. “You are a liar,” said a Winnebago chief. “You told us that the white people were dead or crazy when they were all in their senses and fought like the devil.” Aware that his influence over the tribes was ruined, Tenskwatawa attempted to blame the disaster on his wife. Unbeknownst to him, he claimed, she had touched his sacred medicine bag during “the time of her monthly visitation” and thereby compromised its powers. He pleaded with the villagers to “suffer him once more to try his skill,” but he was instead tied up and threatened with execution as a false prophet. Ultimately, the tribesmen chose to spare his life and await the return of Tecumseh to decide his brother’s fate.

In the American camp, Harrison and his officers were content to simply hold their ground for another day. The Army had suffered heavy casualties, 68 killed and 126 wounded, and the troops were busied building breastworks and burying the dead, who were interred in shallow graves containing five to 10 corpses each. Although the Indians were observed to carry off many of their dead and wounded, the soldiers discovered 36 dead Indians scattered about the camp. The Americans were forced to endure another uneasy, rainy night without campfires, and Funk recorded that “the Indian dogs during the dark hours produced frequent alarm by prowling in search of carrion about the sentinels.”

The next morning, scouts were sent out and reported that Prophetstown had been abandoned by the enemy. Advance details were sent into the village to search for food, and the hungry soldiers gathered up what little corn the Indians had left behind. One Indian woman was found hiding in the village and taken captive, and several fresh graves were discovered containing warriors killed in the battle. The soldiers set fire to the town and left. On the morning of November 9, the Army began the return journey to Vincennes. Back at Fort Boyd, the most desperately wounded were transferred to boats for the return trip down the Wabash. Most of the wounded suffered in wagons until they reached Vincennes on November 18. Two days later, Harrison delivered a message to the territorial assembly optimistically describing the battle as “a complete victory over the hostile combination of Indians.” Hailed as a hero by the frontier population, the governor was execrated as a butcher by his political enemies; a full 20 percent of his troops had been dead or wounded, they whispered, to further Harrison’s personal and political ambitions.

“The British are the Principal- the Indians only Hired Assassins”

In truth, despite his personal heroism, Harrison’s performance during his first independent command had been middling at best, and he had only narrowly succeeded in meeting the campaign’s strategic objectives. His insistence on tight march discipline, often neglected by other commanders, spelled the difference between victory and defeat, but in a notable instance of personal negligence he had unnecessarily exposed his men and nearly brought disaster to his army. Harrison was no stranger to Indian fighting, and his failure to throw out scouts or erect breastworks on the evening of November 6 was an inexplicable and near-disastrous blunder.

In submitting Harrison’s report to Congress, President Madison, who had not directly authorized aggressive military action, nevertheless expressed hope that the breakup of Prophetstown would result in “a cessation of the murders and depredations committed on our frontier.” Ultimately, such hopes were misplaced. Indian attacks continued over the following winter and spring, and an editorial in the Lexington Reporter expressed the general sentiment of the frontier: “The British are the principal—the Indians only hired assassins.” Such provocative language played into the hands of congressional War Hawks, who pointed to the unrest on the frontier as simply another example of British duplicity. When war was finally declared on June 18, 1812, it was done largely to resist heavy-handed British impressment policies at sea. But for the population of the trans-Appalachian west, British intrigue among the Indians was a far more immediate concern.

The War of 1812 constituted the last large-scale opportunity for tribal resistance east of the Mississippi, but it resulted in heartbreaking disappointment for Tecumseh and his followers. Upon his return to Prophetstown in the autumn of 1811, Tecumseh banished his disgraced brother and maintained control over a core group of hostiles, but he failed in his broader efforts to unite the tribes. His prestige, as well as all hopes for a grand Indian confederacy, had been shattered at Tippecanoe by the Prophet’s ill-advised and inept attempt at military campaigning.

“Tippecanoe and Tyler Too”

For William Henry Harrison, the Battle of Tippecanoe and the War of 1812 ultimately resulted in the personal advancement to which he was driven by his ambition. The brilliant campaign slogan “Tippecanoe and Tyler too” carried Harrison and his running mate, John Tyler, to victory in the presidential election of 1840, due in no small part to Harrison’s military exploits 29 years earlier in the pre-dawn darkness at Tippecanoe. In a bit of irony that his old enemy Tecumseh would have enjoyed, Harrison caught pneumonia at his own inauguration and died one month after becoming president—by far the shortest term in American history.

As for Tecumseh, the Shawnee leader and his band loyally served the English Crown as effective auxiliaries but increasingly discovered that their goals ran counter to larger British war aims. Pursued by his American enemies and all but abandoned by his British allies, Tecumseh made a final stand near Ontario’s Thames River on October 4, 1813. Harrison’s troops easily brushed aside a token British force and then caught the Indians in front and flank. Among those killed was Tecumseh. With his death, tribal resistance in the Northwest collapsed. Over the succeeding two decades, any remaining Indian titles were largely extinguished and the natives forcibly removed to open the way for white settlements. Tecumseh’s opposition to such expansion ultimately proved as futile as his efforts to effect Indian unification, but his staunch defense of his own way of life was no less compelling for being unsuccessful. The Great Spirit, he said, “gave this great island to his red children. He placed the whites on the other side of the big water. They were not content with their own, but came to take ours from us. They have driven us from the sea to the lakes. We can go no farther.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments