By Mason B. Webb

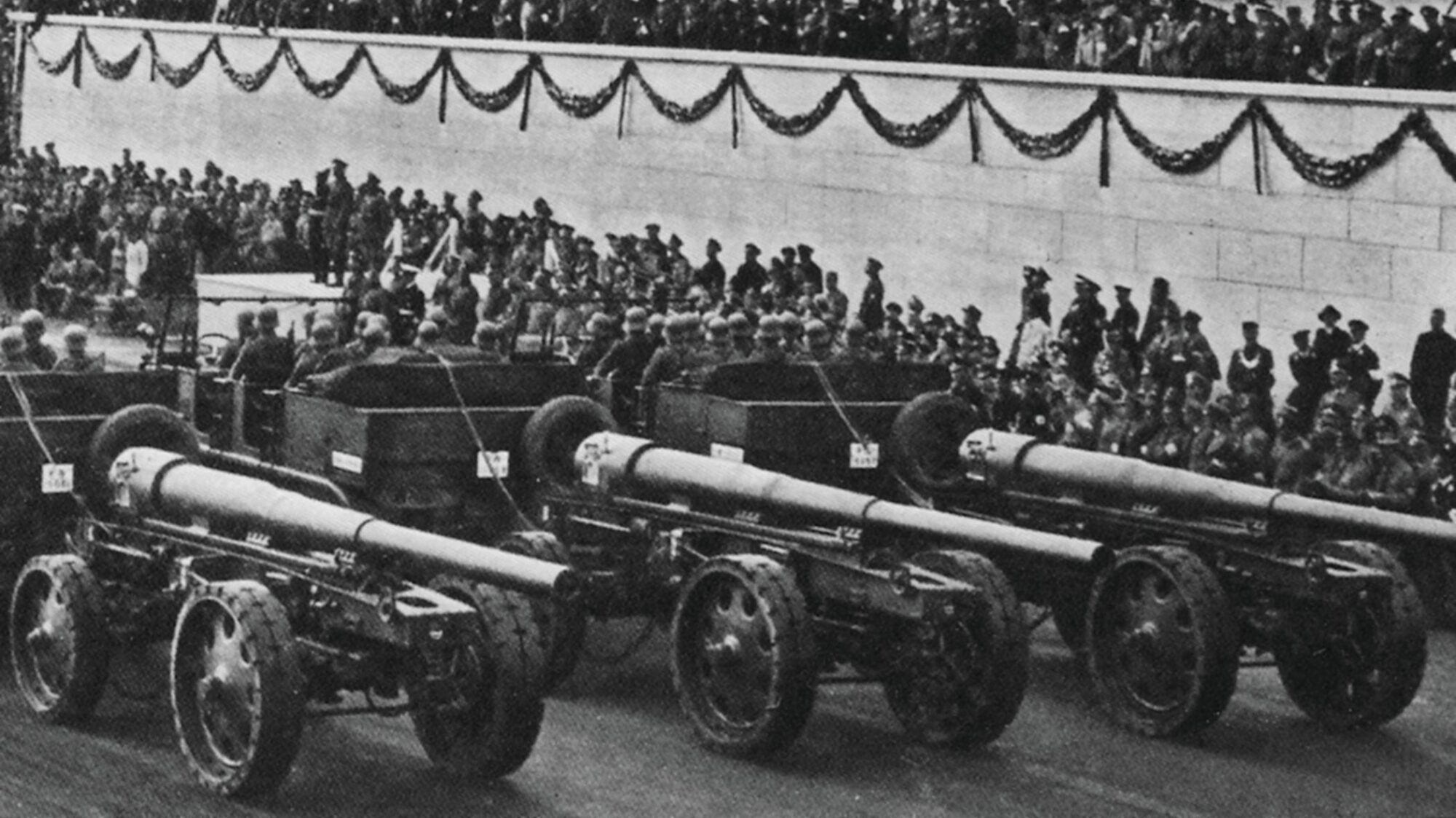

By the late 1930s, no army in the world was as powerful, well organized, or well-equipped as the German Army.

By the late 1930s, no army in the world was as powerful, well organized, or well-equipped as the German Army.

The rise to power by Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party had helped to transform a once broken and demoralized military into a formidable fighting force. The vaunted army, with a troop base and arsenal unsurpassed by any other, was the key to restoring Germany’s greatness.

Throwing aside the restrictions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles at the end of the Great War, Hitler set out to create an armed force second to none––one that would turn his ambitious dreams of world domination into reality. Yet, somehow, this seemingly unstoppable juggernaut, after overrunning virtually all of Europe, suffered an ignominious defeat at the hands of its enemies.

From acclaimed British military historian David Stone comes Hitler’s Army: The Men, Machines and Organization, 1939-1945 (Zenith Press, Minneapolis, 2009, 288 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $40.00) an outstanding book that describes and analyzes every significant aspect of the Wehrmacht and Waffen SS, including their creation, organization, weapons, uniforms, equipment, insignia, logistics, training, and tactics.

Stone paints as complete a portrait of this intimidating force as any ever produced, as well as a careful, penetrating analysis of its conduct in battle, along with its strengths and weaknesses. The result is an essential reference, and a balanced and indispensable aid for those wishing to understand how this once invincible army went from unbeatable to totally beaten in the span of five years.

Filled with charts, maps, and over 300 photos (more than half of them in color), Hitler’s Army is a comprehensive, inside look at one of history’s most feared fighting machines. Essential for any military historian’s bookshelf.

Two Soldiers, Two Lost Fronts: German War Diaries of the Stalingrad and North Africa Campaigns, by Don A. Gregory and Wilhelm R. Gehlen, Casemate, Drexel Hill, PA, 2009, 262 pp., photographs, bibliography, hardcover, $40.00.

The authors built their highly interesting book around two recently discovered diaries of German soldiers––an anonymous soldier of the 11th Panzer Regiment, 23rd Panzer Division, which fought at Stalingrad, and Rolf Krengel, a veteran of the North Africa campaign.

The unique feature of both of these diaries is that they were written as the events unfolded, not months or years after the war when memories had faded. These are real stories, not written for a general audience, or really for any audience at all. As a result, the reader has a sense of the immediacy of combat and the day-to-day lives of ordinary soldiers caught up in a conflict not of their own making.

Interspersed with historical context and commentary by the authors/editors to help the reader grasp the larger picture, the book does a fine job in presenting the small details and realities of war as experienced by the men on the ground. For example, on June 11, 1942, Krengel writes: “We take our trucks and Pumas to Benghazi to fetch our new guns; some are long-barrel ones with folding shields, a new suspension and synthetic rubber tires. On the 15th [of June] news from the front: the British Gazala garrison is surrounded. We are training on the new guns. We write a letter to the Führer thanking him for the new NSU tracked motorcycles [Ketten-Kraftrad]. We go swimming in the sea near Derna. Up at the front, our battle group is fighting south of Tobruk while we build sand castles here in Derna.”

The unknown author of the Stalingrad diary notes on June 29, 1942, that supply shortages are critical and half of his tank regiment is stuck in the mud: “No news of our proposed attack [on a Soviet position near the city]; we repair a few tracks. 6th Co. has the idea of running a platoon of Mk. III’s through a creek bed to get rid of tons of clinging mud but the Captain soon stops that operation. We have to conserve gas. We don’t know how far in the rear our supplies are. Motorized patrols are going out to find a place for assembly prior to our attack.”

The detailed accounts of life on the front lines, and in rear areas––often boring, frustrating, and sometimes terrifying––has never been more finely observed and recorded. Highly recommended.

Phantom Warrior: The Heroic True Story of Pvt. John McKinney’s One-Man Stand Against the Japanese in World War II, by Forrest B. Johnson, Berkeley Caliber, New York, 2009, 340 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, softcover, $16.00.

Phantom Warrior: The Heroic True Story of Pvt. John McKinney’s One-Man Stand Against the Japanese in World War II, by Forrest B. Johnson, Berkeley Caliber, New York, 2009, 340 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, softcover, $16.00.

Before Pearl Harbor, John McKinney was just a simple country boy from a poor family in Georgia, but, as so often happens in the cauldron of war, he found himself forged into a hero and a Marine Corps legend.

In the predawn hours of May 11, 1945, an elite strike force of Japanese soldiers attacked McKinney’s unit encampment on the Philippine island of Luzon. With the rest of his comrades either dead or scattered, the Marine soon found himself standing alone against wave after wave of fanatical enemy troops hell bent on wiping out the Americans. Had it not been for McKinney, they would have succeeded.

When he ran out of bullets, McKinney turned his rifle into a club. Then, when his rifle broke, he turned to his combat knife. When he lost the knife, he resorted to his hands and fists to hold off the attackers. At last, when the assault had ended, John McKinney, his uniform torn and soaked with blood, was the literal last man standing; surrounding him were the bodies of at least 40 Japanese soldiers he had killed single-handedly.

McKinney’s unbelievable heroics had saved many American lives and resulted in his being awarded the Medal of Honor by President Harry S. Truman. Sadly, his extraordinary exploits have faded with time, but thanks to Forrest Johnson’s stirring book the legend will live on.

No Greater Ally: The Untold Story of Poland’s Forces in World War II, by Kenneth K. Koskodan, Osprey, Oxford, UK, 2009, 304 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $24.95.

No Greater Ally: The Untold Story of Poland’s Forces in World War II, by Kenneth K. Koskodan, Osprey, Oxford, UK, 2009, 304 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $24.95.

Other than being where the flashpoint of the European phase of World War II was ignited, Poland’s role in the war has been largely overlooked in the Western media–– which is unfortunate since that country, besides being decimated by both German and Soviet forces and home to the Nazis’ worst death camps, also played a heroic part in the struggle.

Poland, it must be remembered (and which author Koskodan points out), valiantly stood alone in a brave but futile attempt to stave off the German invasion of September 1, 1939. Thousands of her soldiers and airmen then escaped to England to fight another day. Poland’s contributions to victory were immense.

Consider: it was Polish pilots who, flying with the Royal Air Force, helped the United Kingdom win the Battle of Britain in 1940. It was the Poles who stole a German Enigma encoding machine and gave it to the British so that their codebreaking teams at Bletchley Park could deconstruct it and learn how to read Germany’s most secret messages.

It was the Poles who, when Allied armies were stalemated around a monastery atop Italy’s Monte Cassino in 1943, captured this key terrain feature. It was the Poles who fielded infantry and armored forces that won key battles in Normandy following the June 6, 1944, invasion. And it was the Poles who fought just as courageously as their Allied counterparts in Operation Market-Garden, the Allies’ failed attempt to win “a bridge too far” in Holland.

It must also never be forgotten that, following the war, Poland was the sacrificial lamb that a sick American president and a war-weary British prime minister offered up to Josef Stalin in hopes that by doing so the Soviet dictator would be dissuaded from trying to take over the rest of Europe.

As the author says, “The Polish military and the Polish nation were let down by the Allies time and time again. In the end, it would not be the enemies, but the friends of Poland who sealed the country’s fate.”

To read No Greater Ally is to come to understand Poland’s huge contributions to the Allied victory and the shameless way that country was repaid afterward.

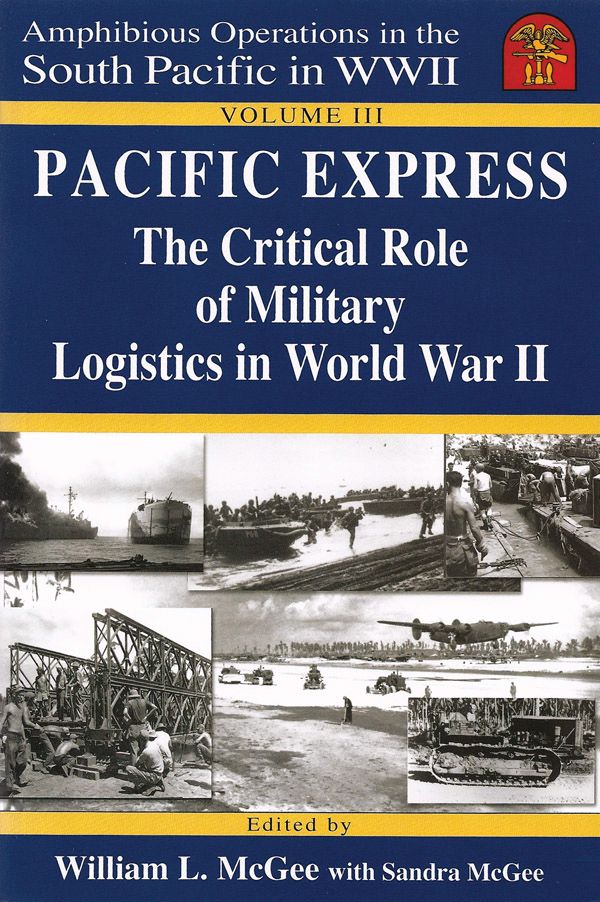

Pacific Express: The Critical Role of Military Logistics in World War II (Volume III in the Amphibious Operations in the South Pacific in WWII series), edited by William L. and Sandra McGee, BMC Publications, Tiburon, CA, 2009, 520 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, softcover, $39.95.

Pacific Express: The Critical Role of Military Logistics in World War II (Volume III in the Amphibious Operations in the South Pacific in WWII series), edited by William L. and Sandra McGee, BMC Publications, Tiburon, CA, 2009, 520 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, softcover, $39.95.

It is an indisputable fact that, for every one American fighting man in combat in World War II, there were 10 others behind him, providing the vital support he needed. Therefore, while it is understandable that the combat soldier (or sailor or airman or Marine) gets the lion’s share of praise and coverage in histories, the role of the support personnel is no less important or heroic.

After all, wars cannot be won or even fought for very long without an efficient logistics system, whether that means delivering ammunition, fuel, spare parts, food, medicine, weapons, clothing, equipment, or all the other supplies required to sustain operations on far-flung battlefields. Even getting troops to those battlefields is a gargantuan but little appreciated effort.

Giving this vital cog in the military wheel its due are William L. and Sandra McGee, editors of Pacific Express. This 520-page work is not just a dull assemblage of charts, facts, and statistics showing the amounts of tonnage moved from one location to another, but a collection of well-written articles about flesh and blood efforts to get the necessary goods to the right people at the right place and at the right time.

The McGees have included chapters on the essential contributions of the millions of homefront workers in the defense plants who built the ships, tanks, and aircraft; the U.S. Navy Seabees, and Army and Marine Corps engineers who built and manned the many advance bases on tiny dots of land in the Pacific; the Navy crews who manned the fleet’s mobile service squadrons; and the civilian sailors, Coast Guardsmen, and U.S. Navy gun crews who manned the thousands of transport ships, oilers, repair ships, and landing craft throughout the Pacific Theater for nearly five years. Many did so at extreme danger to themselves, and not all came home to tell the story of their unselfish service.

After reading this book, one will be in awe of the tremendous role performed by the logistics services.

Short Bursts

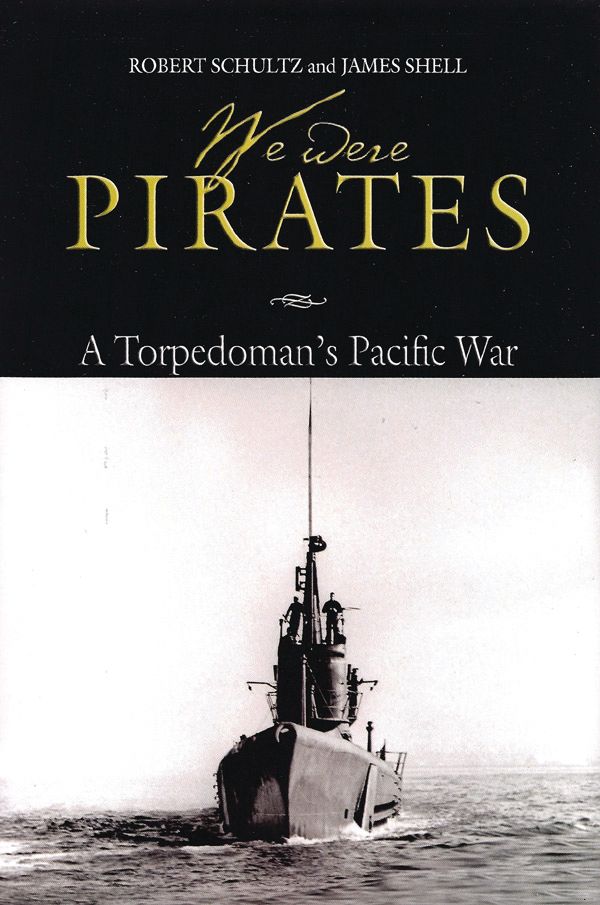

We Were Pirates: A Torpedoman’s Pacific War, by Robert Schultz and James Shell, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2009, 212 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $34.95.

We Were Pirates: A Torpedoman’s Pacific War, by Robert Schultz and James Shell, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2009, 212 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $34.95.

Torpedoman Robert Hunt managed to survive 12 war patrols aboard the submarine USS Tambor. During the course of the war, Hunt and Tambor seemingly were everywhere in the Pacific––in Pearl Harbor just a few days after the devastating Japanese raid; hunting for enemy ships at the Battle of Midway; ferrying guns and supplies to guerrilla fighters in the Philippines; and dodging an unrelenting underwater barrage of Japanese depth charges.

Hunt kept a running account of his experiences, both on shore and at sea, in a diary aboard Tambor. The accounts are candid and vivid, and provide a unique perspective not often found in general histories of the submarine force.

Co-authors Shultz and Shell have surrounded Hunt’s written and verbal accounts with information from additional sources, including official records, crew letters, captains’ reports, and historical research. An outstanding description of war beneath the waves as seen and lived by one submariner.

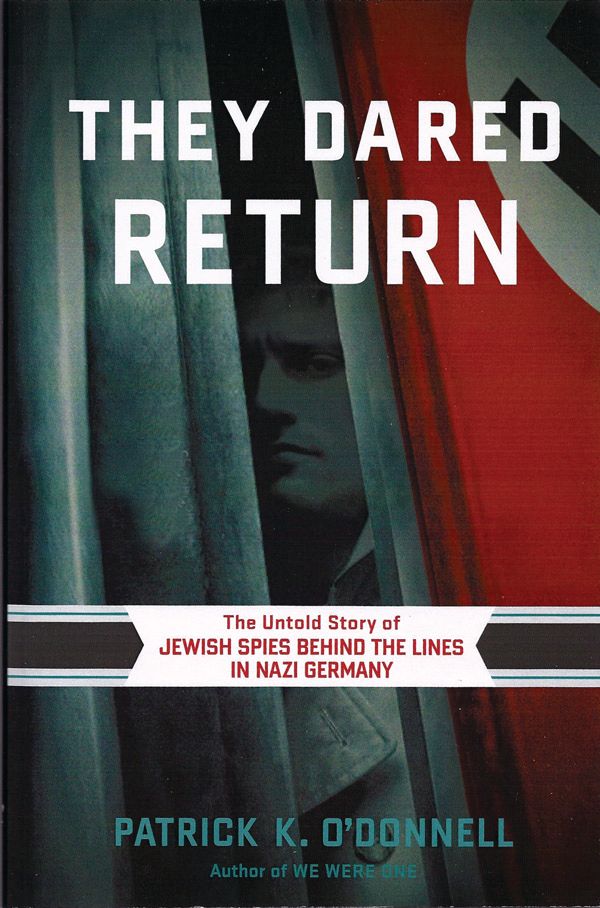

They Dared Return: The Untold Story of Jewish Spies Behind the Lines in Nazi Germany, by Patrick K. O’Donnell, DaCapo Press, Cambridge, MA, 2009, 256 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $32.95.

They Dared Return: The Untold Story of Jewish Spies Behind the Lines in Nazi Germany, by Patrick K. O’Donnell, DaCapo Press, Cambridge, MA, 2009, 256 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $32.95.

In 1942, with the Nazi juggernaut having overrun most of Europe and with a general roundup and slaughter of Jews fully underway, a few refugees who had escaped to America made the fateful decision to return to their homeland in order to end the persecution of their people.

Author O’Donnell tells the story of five such men in his new book, They Dared Return. Joining the OSS (Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner to the CIA), Fred Mayer and four other Jews were chosen to infiltrate the Third Reich. Formed into small teams, they were dropped into German-controlled territory near the Brenner Pass in the closing months of the war along the dangerous, heavily fortified Austrian Alps to gather important information and pass it on to the Allies.

The assignment would be the most difficult challenge of their lives, a supreme test of their courage, strength, perseverance, and patriotism, but the rewards for success would be great. More than the gratitude of their adopted homeland, success also meant helping to bring a swift end to the war and perhaps saving the lives of family and friends.

Of course, such covert activities would bring torture and death if they were discovered by the enemy, so the book reads like a terrific spy novel, but it is all fact.

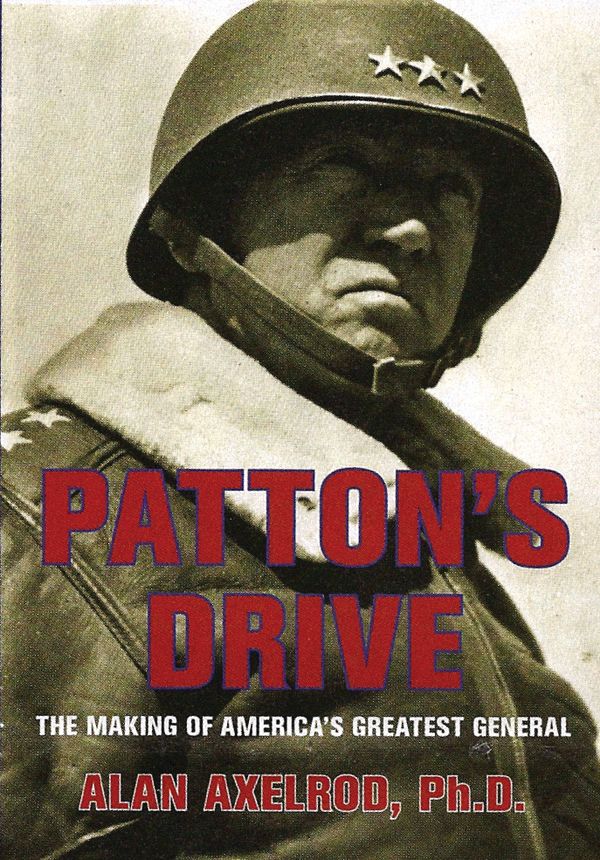

Patton’s Drive: The Making of America’s Greatest General, by Alan Axelrod, 2009, Lyons Press, Guilford, CT, 304 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover $24.95.

Patton’s Drive: The Making of America’s Greatest General, by Alan Axelrod, 2009, Lyons Press, Guilford, CT, 304 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover $24.95.

Lieutenant General George Smith Patton, Jr. remains a controversial, larger-than-life figure 65 years after his death from injuries sustained in a car accident. War correspondent Andy Rooney hated him and his hard-driving style of command, as did thousands of men who served under him. Yet, thousands more were devoted to the leader who swore like a drunken sailor but cried like a child when his men died in battle.

What drove Patton to become the towering figure we remember today? Alan Axelrod has spent years researching the general’s background, especially his formative years as the son of a wealthy California family, a cadet at VMI and West Point, an Olympic athlete, a cavalry officer in the 1916 Punitive Expedition in search of Pancho Villa, and as a tank brigade commander in World War I, to see what made him tick.

Patton’s Drive is a terrific bit of writing and analysis of a giant in the history of warfare.

Deciphering the Rising Sun: Navy and Marine Corps Codebreakers, Translators, and Interpreters in the Pacific War, by Roger Dingman, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2009, 340 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $34.95.

Deciphering the Rising Sun: Navy and Marine Corps Codebreakers, Translators, and Interpreters in the Pacific War, by Roger Dingman, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2009, 340 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $34.95.

Knowing what an enemy is thinking and planning is just as vital to wartime success as is engaging him on the battlefield. Highly trained language specialists were employed in all theaters of World War II, but none to greater effect than in the Pacific Theater.

Here, 1,200 men (and women, too) who had mastered the difficult Japanese language were employed to break the Japanese military codes, decipher radio messages, and pass along the information thus gleaned to higher headquarters so that steps could be taken to thwart enemy intentions.

Because of the fine work performed by these Navy and Marine Corps specialists, Japanese convoys were intercepted, formations of enemy planes shot down, enemy attack plans countered, and thousands of Allied lives saved. It is not exaggerating to say that the codebreakers and combat interpreters hastened victory.

Dingman’s book, the first to document the vital role played by Americans not of Japanese ancestry, describes the selection, training, and service of this group during the war and their postwar contributions toward turning one-time bitter enemies into the closest of friends.

Hero Street USA: The Story of Little Mexico’s Fallen Soldiers, by Mark Wilson, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2009, 192 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $19.95.

Hero Street USA: The Story of Little Mexico’s Fallen Soldiers, by Mark Wilson, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2009, 192 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $19.95.

During the Great Depression, Second Street in the small Illinois town of Silvis was home to a community of Mexicans who, in 1917, had fled the revolution raging in their home country.

In 1971, Silvis was officially renamed “Hero Street USA” to commemorate the fact that it had the highest per capita casualty rate of any neighborhood during World War II. Wilson’s book is the first to recount the saga of sacrifice, pride, and patriotism that marked the town’s contribution to the war effort.

Using poignant family memories, soldiers’ letters, interviews with relatives, and firsthand combat accounts, Wilson tells the compelling stories of nearly 80 young Mexican American men who volunteered to fight for their country in World War II and Korea––and of the eight who never came home. The lives of these men were later honored as “a lesson in perfect, unselfish patriotism” by the Illinois House of Representatives. Yet, the surviving veterans faced many struggles with discrimination and intolerance when they returned. A moving portrait of one group’s devotion to duty and the less than honorable aftermath.

Join The Conversation

Comments