By Brad Hall

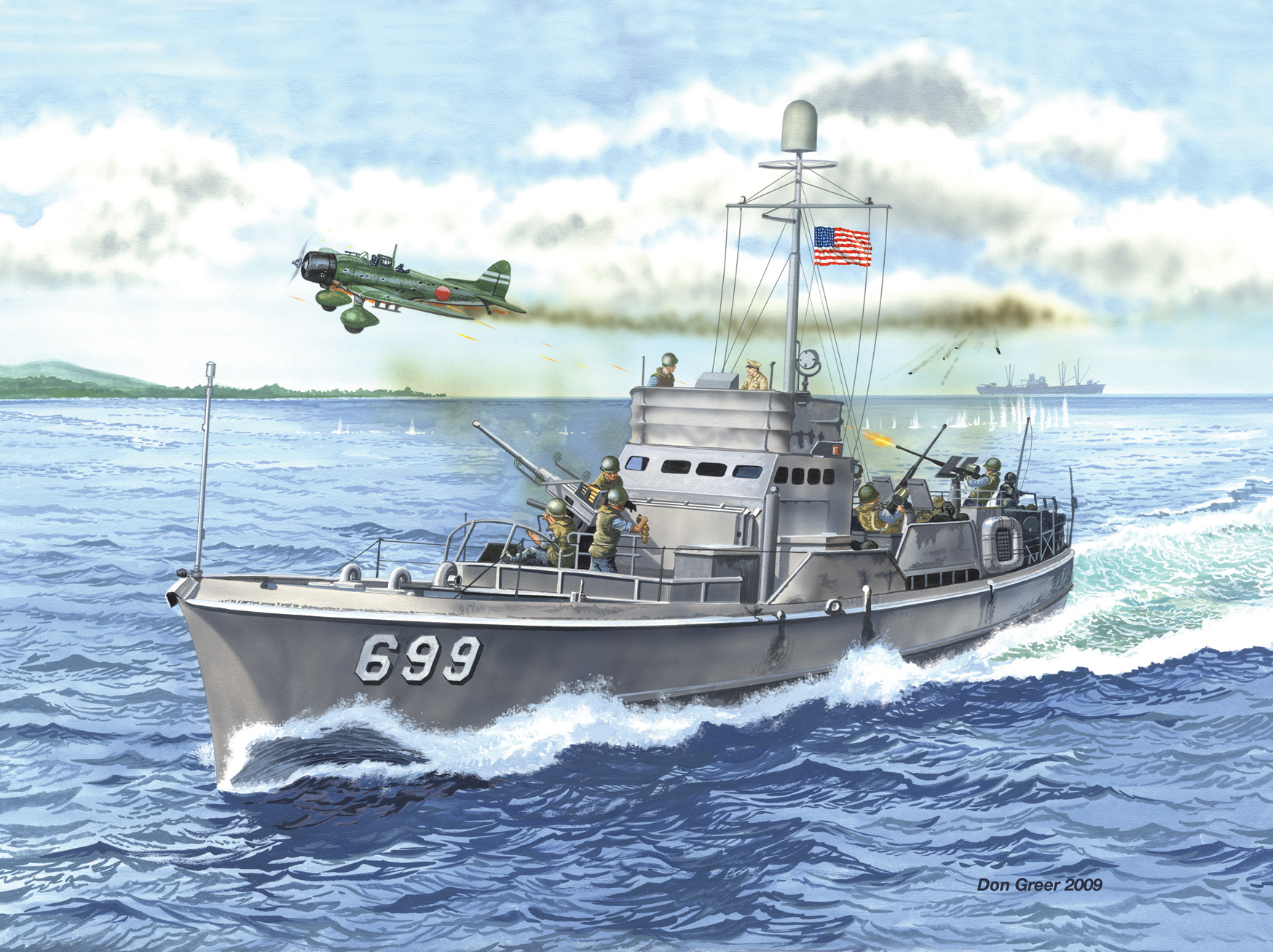

The crew of Submarine Chaser 699 (SC-699) watched with dread as the Japanese fighter aircraft slammed into the ocean, cartwheeled off the ocean’s surface, and spun toward its deck. Minutes before the crew members had fired all their guns in an effort to withstand the assault by four Japanese aircraft. In that lightning-fast encounter between combatants, both sides had been grimly determined to inflict maximum damage on each other.

As the enemy fighter plane spun toward them, SC-699’s crew had only a few seconds to reflect on the implications. The out of control enemy plane posed a mortal danger to their fragile bodies and their equally fragile wooden ship, which was part of a flotilla of U.S. ships anchored off Biak Island 900 miles from the Philippines. There was nothing they could do except brace for the impact and hope and pray their lives might be spared in the certain catastrophic event that was unfolding.

In World War II, the United States built 580 wooden ships known as submarine chasers for the Navy. These ships were 110 feet long and 17 feet wide. They were armed with one 40mm mounted gun, two twin-mount .50-caliber machine guns, several depth charge projectors, and Mk 20 Mousetrap rockets. The ships boasted a full complement of 27 crew members—three officers and approximately 24 men. The reason the submarine chasers were built from wood was to conserve steel and other metals for larger vessels, while still being able to use smaller shipyards in the effort to create war materials. In the war, these little ships saw a lot of action.

SC-699 became known in the Pacific Theater for being in the thick of things, eventually being nicknamed “The Shooting 699” by Admiral Daniel E. Barbey during the attack on Arawe Island in December 1943. During that fight, SC-699 rescued 71 wounded men. For this courageous sea rescue, her skipper, Lieutenant (j.g.) James W. Foristel of St. Louis, Missouri, received the Silver Star.

For 11 months, SC-699 was involved in 11 major operations in the Pacific. But the battle where the SC-699 really shined and survived was at Biak in the Schouten Island group near New Guinea in May 1944.

Biak was the next target in General Douglas MacArthur’s island hopping strategy of reclaiming the Philippines. For the month before the invasion, the Allies shelled and bombed Biak with 700 tons of ordnance. The island also contained three airstrips and a supply base. This was important as Biak was close enough to the Philippines to allow land based bombers to reach the islands.

There were nearly 11,000 Japanese troops between the Seventh Fleet and victory. In contrast to the American view of Biak, the Japanese did not designate the island as absolutely vital; nevertheless, the commanders of the 2nd Area Army and 7th Air Division decided to defend the island to the last man.

At 6 pm on May 25, 1944, SC-699 left Humbolt Bay, Hollandia, to assist with the invasion of Biak Island, known as Operation Horlicks, with the rest of the Seventh Amphibious Force, Seventh Fleet. SC-699 also carried Boat Control Officer Lt. Cmdr. Phillip Christian Holt.

However, on May 26, Japanese convoy M-20, consisting of nine ships, headed west from the military base on Kao Bay, Halmahera. Back in Halmahera, 30 more ships awaited orders. Despite the growing threat of Operation Horlicks, the escort and defense mission could not simply be abandoned to defend Biak. The 23rd Air Flotilla commander, Vice Admiral Yoshiaki Itoh planned to attack the enemy off Biak with two Mitsubishi A6M Zero) and seven Type-1 Nakajima Ki-43 Oscar fighters temporarily under his command.

At this time, the 5th Hiko Sentai (Air Regiment) of the 3rd Air Brigade was on the western tip of New Guinea near Efman Island preparing to escort another convoy from Sorong to Manokwari. When word of the impending attack reached Major Katsushige Takada, commanding officer of the 5th Hiko Sentai, he decided to join the fray with four two-engine Kawasaki Ki-45 Nick fighters, in addition to Itoh’s forces. Takada made arrangements for Captain Yasuhide Baba to assume the escort duties assigned to his unit and began picking the remaining members of his understrength attack squadron.

At 6:30 am on May 27, all ships were lying off intended beach assault areas. Cruisers and destroyers began bombarding the island. SC-699 was stationed 2,000 yards offshore on the west side of the landing area to act as a control ship.

Shortly after 2 pm, Takada and his squadron conducted a sortie from Efman Island with the two-engine planes, despite the fact that these planes were deemed unsuitable for this type of mission. The Zeros and Oscars were not able to be prepared in time, so Takada was only able to sortie with the four Nick fighters. The plan was to engage the enemy ships and be back to Efman Island no later than 6 pm, which was before sundown.

“Although no orders have been received from the higher headquarters, I cannot possibly ignore and leave the friendly forces on Biak to their fate,” Takada told his crew members before takeoff. “Now, we shall depart to attack the enemy ships there.”

After passing Noemfoor Island, the Japanese fighter squadron observed several American P-47 Thunderbolt fighters between the clouds and were able to slip through undetected. When they arrived over Biak, the Japanese team saw 14 Allied ships in the Yapen Strait shelling Biak.

At 5:15, four Japanese planes were sighted at an altitude of around 2,000 feet coming from Sorong, the only attack from the air on this day of the battle. From the ships, the Japanese planes appeared to fly directly out of the sun. SC-699 ship commander Foristel reported that he saw five enemy planes and that at least two of them were Aichi D3A dive bombers, commonly referred to as Vals by the Allies. After comparing images of Vals and P-47s, it is likely that Foristel mistook P-47s for Vals. Nowhere in his report does he mention P-47s.

Foristel reported two of these single-engine planes dropped bombs on the landing area and became engaged by heavy gunfire from both beach and ship mounted guns. One of them crossed the SC-699 at an altitude of 400 feet and was hit by at least 100 rounds of ammunition from that ship alone. This plane was seen to crash off the starboard bow of the SC-699. The other was seen to crash by the water’s edge. Again, the only single-engine planes reported to be in the air that day were the P-47s. It is possible that the SC-699, as well as other ships, contributed to the shooting down of friendly craft. However, no evidence specifically pointing to this has been discovered.

Although P-47s do resemble Vals, the Vals had fixed gear, while the P-47 did not. The two were commonly painted similar colors as well, except for the red hinomaru (meatball) of the Japanese planes and the blue and white star on the side of the American planes. Curiously, Foristel reported seeing five planes.

Foristel stated that the three remaining planes were two-engine, yet appeared smaller than the common Mitsubishi G4M Betty bombers, musing in his report that these planes could be a new type similar to the Germans’ Messerschmitt Bf-110 fighter. In his report, Foristel drew a map and located what each plane did as far as where it came from and where it crashed. In this map, he does not mention a fifth plane as he only saw the actions of four planes, two Nicks and the unknown single-engine planes.

Two Nicks, one piloted by Sgt. Maj. Takahiro Kudo (rear seat: Sgt. Maj. Hiroshi Iwamoto) and the other piloted by 1st Lt. Toshio Okabe (rear seat: Sgt. Maj. Masanori Nozaki) crashed, most likely near the edge of the beach. Takada’s plane sustained damage, knocking out the left engine.

After the first two planes were shot down, the remaining two planes, piloted by Sgt. Maj. Chugo Matsumoto and Takada himself, tried to escape the battle. Somewhere along the way, Matsumoto’s plane crashed alongside the water’s edge about one and one-half miles east of where the second single-engine plane crashed.

Takada’s plane passed over the beach and approached the SC-699 within 1,000 yards off her port bow and was met with heavy fire from the ship’s 40mm gun, as well as the port guns. The plane then turned east, trying to escape the battle. Takada told his observer, Sgt. Maj. Toshio Motomiya, that they were going to turn around to get even with the enemy for killing his men.

Takada planned on circling back and taking out the destroyer USS Sampson which was just a few hundred feet to the port side of SC-699. Seemingly out of nowhere, the P-47s reappeared. Takada shot one of them down, but he and his plane sustained even more damage in the dogfight. The right engine started catching fire. During this time, SC-699’s guns were still blazing at Takada, the 40mm, both 20mm guns, and the twin .50-caliber were all firing. From the first shot to the last shot, SC-699 expended 1,086 rounds of ammunition from all five guns in a battle that lasted no more than two minutes.

Injured, Takada told Motomiya in a faint voice through the speaking tube to send a telegram to the field as they were soon to crash. Motomiya replied that he could not since the radio equipment had been destroyed in the fight. Takada acknowledged this by saying, “Oh well, can’t be helped, can it?” A few seconds later, he continued, “Long live the emperor!” and pulled a gun out of his pocket and shot himself in the head.

This plane just barely missed crashing into the Sampson. About 30 yards away from SC-699’s port side, the plane struck the water with its left wing tip. Motomiya somehow was thrown out of the plane as it flipped over into the SC-699’s midsection.

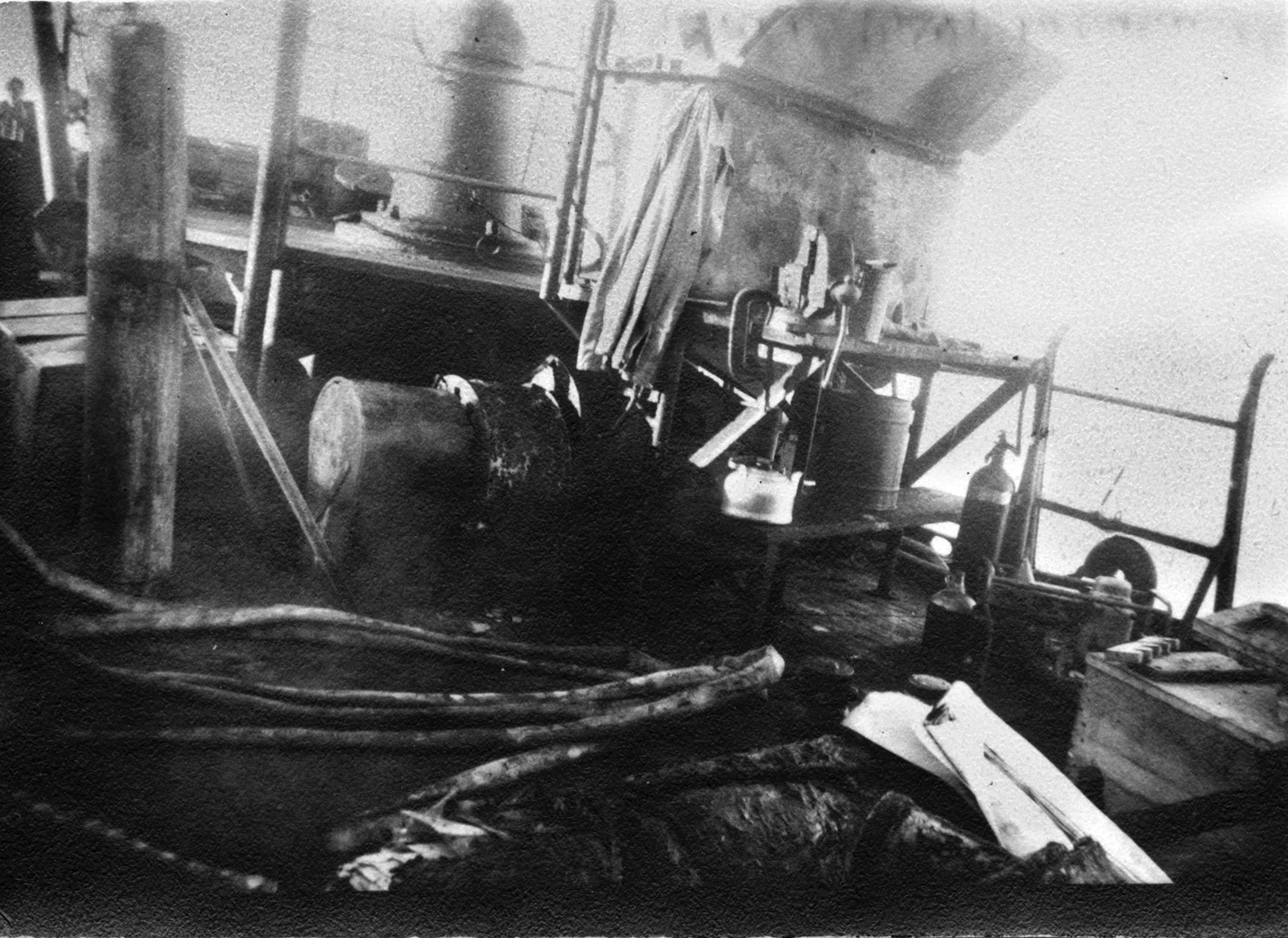

The ship was ablaze. Pieces of the Nick were scattered all over the deck and in the water. A gasoline explosion and fire erupted with the collision.

Sixteen of the SC-699’s 25 crew members, including Foristel, the recorder, and the gunnery officer, either jumped off the ship or were knocked off. In his report, Foristel noted, “The recorder of his own knowledge does not know which was the cause either in the case of himself or any other man.”

At this time, the only remaining officers on the ship were Lieutenant (j.g.) Orville Wahrenbrock, executive officer, and Boat Control Officer Lt. Cmdr. Holt. Holt took command, stating later that the reason he took command without being ordered to was “the skipper had gone overboard without leaving any orders.” Holt received the Navy Cross for his actions in saving the ship.

In his report to Foristel, Wahrenbrock stated, “As soon as I saw you leave the ship from the flying bridge over the port side, I went over the bridge and onto the forecastle. Several wounded men had gathered there, and I directed the pharmacist’s mate to take care of them.” At this point, the recorder and a couple other members of the crew had climbed back aboard.

Holt ordered those who remained aboard to extinguish the fire and aid those who were injured. The fleet tug USS Sonoma came alongside the SC-699 within five minutes and helped quell the blaze. Wahrenbrock went over to the Sonoma to help that crew connect water hoses to combat the fire. He then directed firefighting efforts back on the SC-699. Several crew members dropped 24 crates of hot ammunition over the side.

Crew members who were knocked into the water were rescued by the SC-734. The injured were transferred to the LST-459. In all, from the moment of impact to putting the fire out and all uninjured crew members returning to the SC-699 was about 20 minutes.

SC-699 suffered two dead. Motor Machinist Mate 1/c Allen Hagmann was on deck when the Nick hit the ship and was washed out to sea. His body was never recovered. Radioman 2/c V-6 William Henry Harrison remained at his 20mm gun station and fired until the plane crashed into the ship at his gun. His charred body was removed from the harness, rigid, still in firing crouch position. He died one hour later aboard LST-459.

Motor Machinist Mate 3/c Robert G. Marx remembered that day well. He was the man who strapped Harrison into his position at the 20mm on the day of the crash. Just before the crash, Marx saw the Japanese pilot. The pilot was smiling. Just then, the pilot was cut in half, top down, most likely by a direct hit from the .50-caliber. Then, he crashed into the ship.

After that, Marx fell unconscious into the ocean. When he awoke, there was fire all around him. A ship came near. A sailor reached out to grab Marx, but a layer of skin slid off his arm, and he fell back into the ocean. After he was finally brought aboard, he was covered with a layer of wax embedded with penicillin.

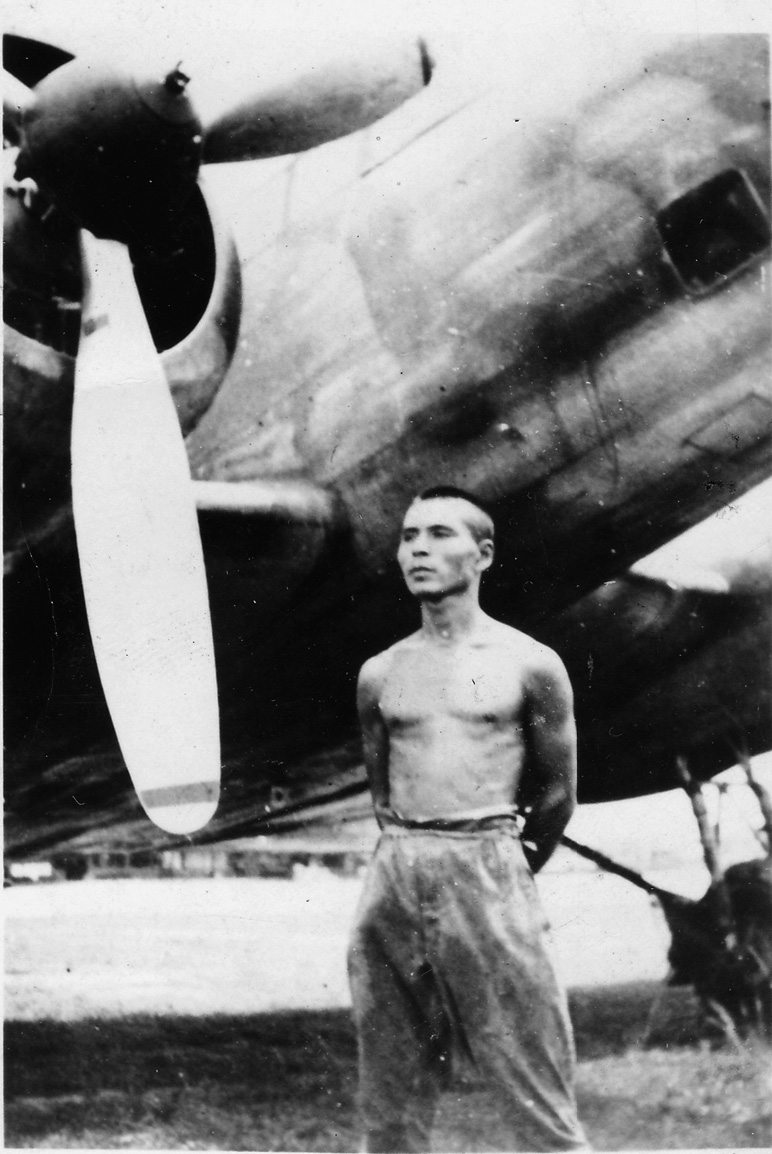

Pieces of Takada’s Nick were found on SC-699. Inside a cigarette case, American sailors found several pictures of Japanese pilots standing next to their aircraft, most likely pictures of the fighter team they had just fought. The identities of the pilots in the photographs has yet to be verified.

That night, the SC-699 remained moored to the LCI-31 while members of the SC-699 and LCI-31 conducted emergency repairs. The hole in the side of the ship was patched using plywood and Navy blankets. The next day SC-699 was towed to Hollandia for further repairs. The crew was transported to Cairns, Australia. SC-699 emerged three months later ready to go back to war.

Motomiya awoke in the water sometime after the crash. He spent two nights in the water before eventually washing up on the west coast of Biak Island, where he again lost consciousness due to a combination of hunger and cold. He was rescued by natives who took him to the nearby Imperial Japanese Navy base in Manokwari on the Vogelkop Peninsula (Bird’s Head Peninsula). On June 1, 1944, he flew back to Efman.

Motomiya’s report diverges from the Allied record of events. He states that Kuo’s and Okabe’s planes crashed on destroyers and sank both. He went on to say two more destroyers were badly damaged due to their actions. Again, according to the Allied version of events, only SC-699 sustained damage.

On June 10, General Juichi Terauchi, commander of the Southern Area Army, presented Takada and his men a posthumous citation. Takada also received a posthumous promotion to lieutenant colonel. They also became the forebears of what would be called Tokubetsu Kougekitai, or Tokku-tai, more commonly referred to as kamikaze. The Japanese kamikaze campaign began several months later in October 1944.

Some historians believe the designation of this incident as the first kamikaze attack is inaccurate. They point out that kamikaze pilots were not allowed to return. In the middle of this battle, Takada almost decided to escape but returned to the fight, even though he most likely knew he would die if he did.

Another reason why this could not be a first kamikaze is due to an earlier incident that occurred on February 1, 1942, when Lieutenant Kazuo Nakai of the Imperial Japanese Navy attempted to crash his plane, a Type-96 land-based attack bomber (Mitsubishi G3M Nell) into the USS Enterprise off the Marshall Islands.

While SC-699’s role in the Battle of Biak was short, the battle raged on from May 27, 1944, to June 22, 1944. When it ended, more than 6,000 Japanese were dead, including Katsume, who killed himself. The Allies suffered slightly more than 400 casualties.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments