By John Walker

The ground around Manassas, Virginia, was not auspicious for Union Army forces in the first two years of the Civil War. It was there, on July 21, 1861, that a Union army broke to pieces on the bulwark of Brig. Gen. Thomas Jackson’s brigade, earning the Confederate general the sobriquet of “Stonewall” and his men the proud appellation the Stonewall Brigade. The scene of the first major battle of the war, Manassas was about to become the focus of attention once again.

The failure of Maj. Gen. George McClellan’s attack on Richmond prompted President Abraham Lincoln to order the withdrawal of the Army of the Potomac from the peninsula to Washington in the summer of 1862. Lincoln then summoned Maj. Gen. John Pope from the western theater and gave him command of the newly created Union Army of Virginia. Formed by the consolidation of the commands of Generals Irvin McDowell, Nathaniel Banks, and John C. Frémont, the new army was tasked with covering McClellan’s movement and protecting the nation’s capital.

By mid-July, Pope’s 51,000-man army (which would soon receive reinforcements, mostly from the Army of the Potomac, that would bring its strength up to more than 70,000 men), had moved south to threaten Richmond’s access to the Shenandoah Valley. Although McClellan’s withdrawing forces were still perceived to be a threat to Richmond, General Robert E. Lee felt that Pope now represented the more immediate threat and sent reinforcements to Jackson with orders to counter Pope’s forces and suppress the new Union army.

On August 3, McClellan finally received orders to evacuate the peninsula, thus removing the dual threat to Lee’s troops and allowing him the opportunity to concentrate on Pope exclusively. On August 13, 10 of Lee’s brigades, commanded by Maj. Gen. James Longstreet, joined Jackson in the reorganized Army of Northern Virginia. Lee’s aim was for Jackson to take his corps around Pope’s flank, cutting off his supply lines, at which point Longstreet’s corps would rejoin him to defeat Pope before the rest of McClellan’s slow-moving reinforcements could combine with Pope.

Backed by Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry, Jackson’s 23,000-man corps marched 54 miles in two days. On the evening of August 26, Jackson captured Bristoe Station on the Orange & Alexandria Railroad, destroyed several trains, and threatened to cut the Union lines of communication with Washington. The first sign of serious trouble in his army’s rear reached Pope at about 8 o’clock on the night of August 26, just before the wires went dead, when the telegraph operator at Union-held Manassas Junction reported that “enemy cavalry has fallen upon the railroad.”

Confederate Brig Gen. Isaac Trimble was en route from Bristoe Station to Manassas Junction, four miles up the line, with two regiments of infantry. Before midnight he easily captured the huge but lightly defended Union supply depot. The next morning, with Jackson’s corps firmly between his army and Washington, Pope ordered the precipitous withdrawal of almost his entire force from the Rappahannock line into an all-out pursuit north to corral Jackson’s host.

For two days Pope exhausted his combined force in a massive, futile search for Jackson, first ordering his units to converge on Manassas Junction. When Pope arrived there in person at noon on the 28th to find his antagonist gone, he concluded wrongly that the Confederate divisions had moved east to Centreville, and he rerouted his scattered units there. Repeated marches and countermarches in the Virginia heat took a heavy toll on officers, enlisted men, and horses.

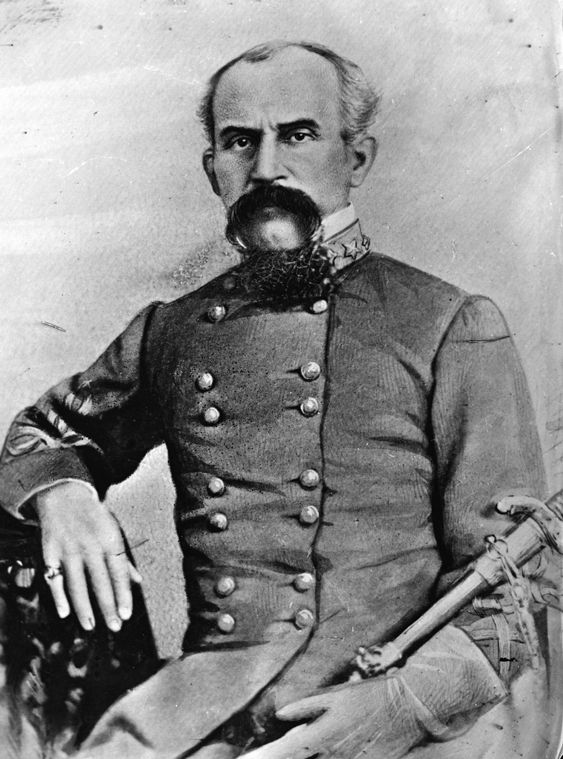

Meanwhile, Jackson had actually moved his men in the opposite direction. After ransacking the massive supply base at Manassas Junction and putting the torch to whatever his men could not consume or carry away, Jackson consolidated his three divisions several miles to the northwest along Stony Ridge north of the tiny hamlet of Groveton, not far from the old Manassas battlefield. Jackson had chosen a superb defensive position a few hundred yards up the hill from the strategic Warrenton Turnpike. Hidden in the fields and woods behind the embankments of an unfinished railroad, he could monitor Union movement on the turnpike while awaiting the arrival of Longstreet’s wing of the Army of Northern Virginia. The Confederates had an excellent view of the turnpike to their front and could easily launch a strike against an isolated unit of Pope’s army moving along the pike.

Late on the afternoon of August 28, Jackson was reconnoitering the ridge to his front when blue-coated troops belonging to the division of Brig. Gen. Rufus King came into view, marching east along the pike in the direction of Centreville. As his worried staff watched, Jackson rode down the ridge for a better look, trotting slowly back and forth within musket range of the blue infantry columns, which paid him no heed. As the sun was about to set, King’s column drew abreast of Jackson’s position. Jackson rode back to his officers on the ridge and calmly told them, “Bring up your men, gentlemen.” Within minutes the Battle of Brawner’s Farm erupted in earnest.

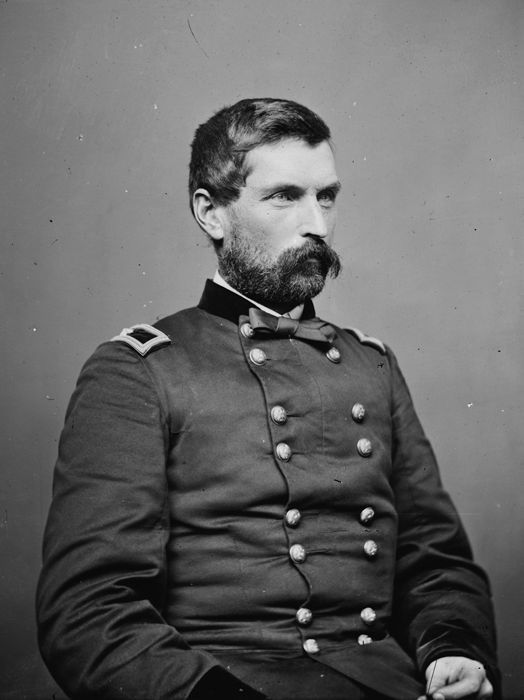

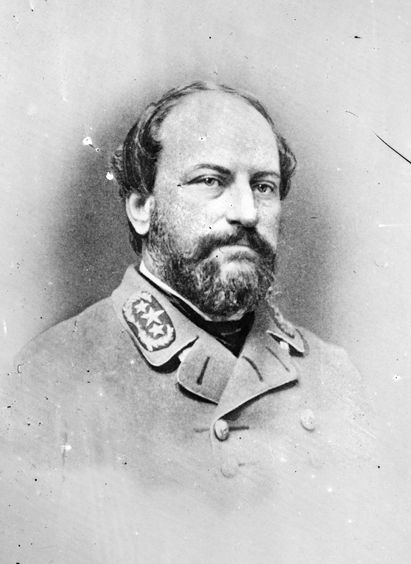

King’s division consisted of one brigade of all Westerners—three regiments from Wisconsin and one from Indiana—under the command of Brig. Gen. John Gibbon, and three additional brigades of untested troops from New York and Pennsylvania. Though yet to see action in the war, Gibbon was an experienced Regular Army officer, a veteran of the Mexican and Seminole Indian Wars. He had also served as an artillery instructor at West Point, and was the author of The Artillerist’s Manual, a scientific treatise on gunnery used by both sides in the war. Gibbon was appointed brigadier general of volunteers in 1862 and given command of King’s Wisconsin brigade.

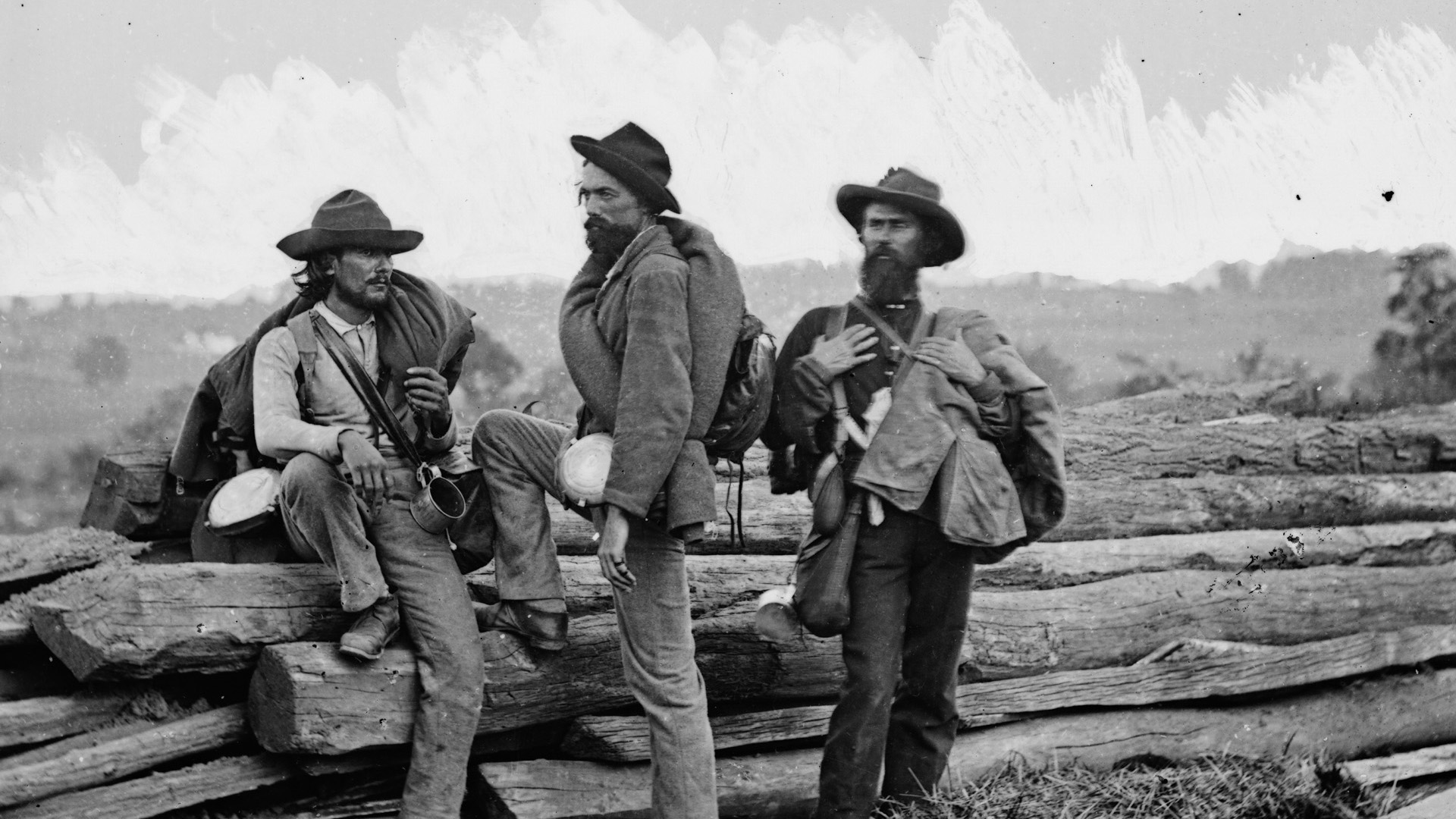

Demanding the same level of discipline and professionalism from these volunteer Westerners that he demanded of his Regular artillerymen, Gibbon quickly set about drilling his troops and improving their appearance, ordering them to wear white leggings and, rather than the standard Union kepi, black Hardee hats, known as the Model 1858 Dress Hat. These tall hats were adorned with a plume, giving the brigade a distinctive appearance, and it soon became known, logically enough, as the “Black Hat Brigade.” Of Gibbon’s four regiments, only one—the 2nd Wisconsin—had seen action in the war, 13 months earlier on this same ground.

junction was fought over frequently during the war.

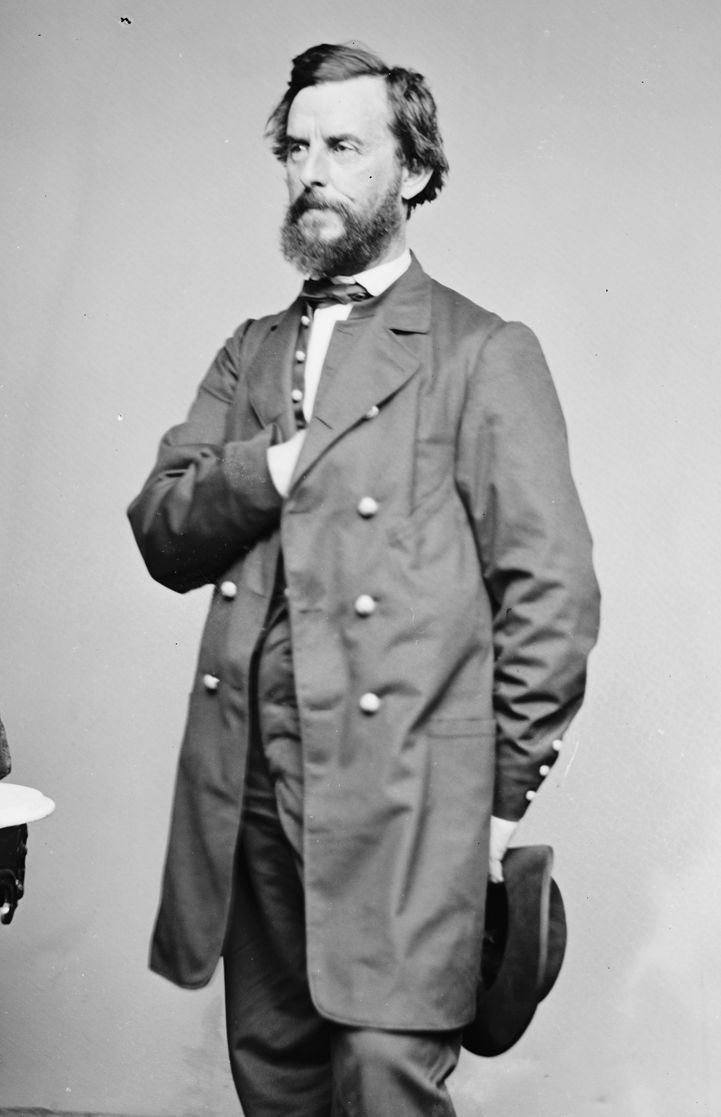

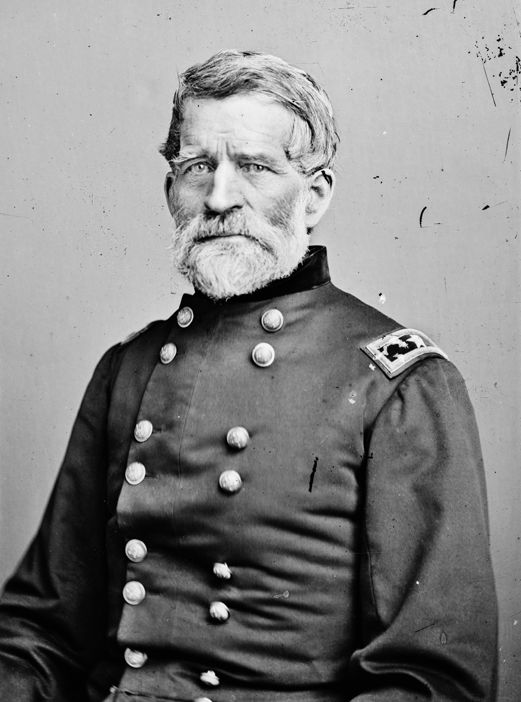

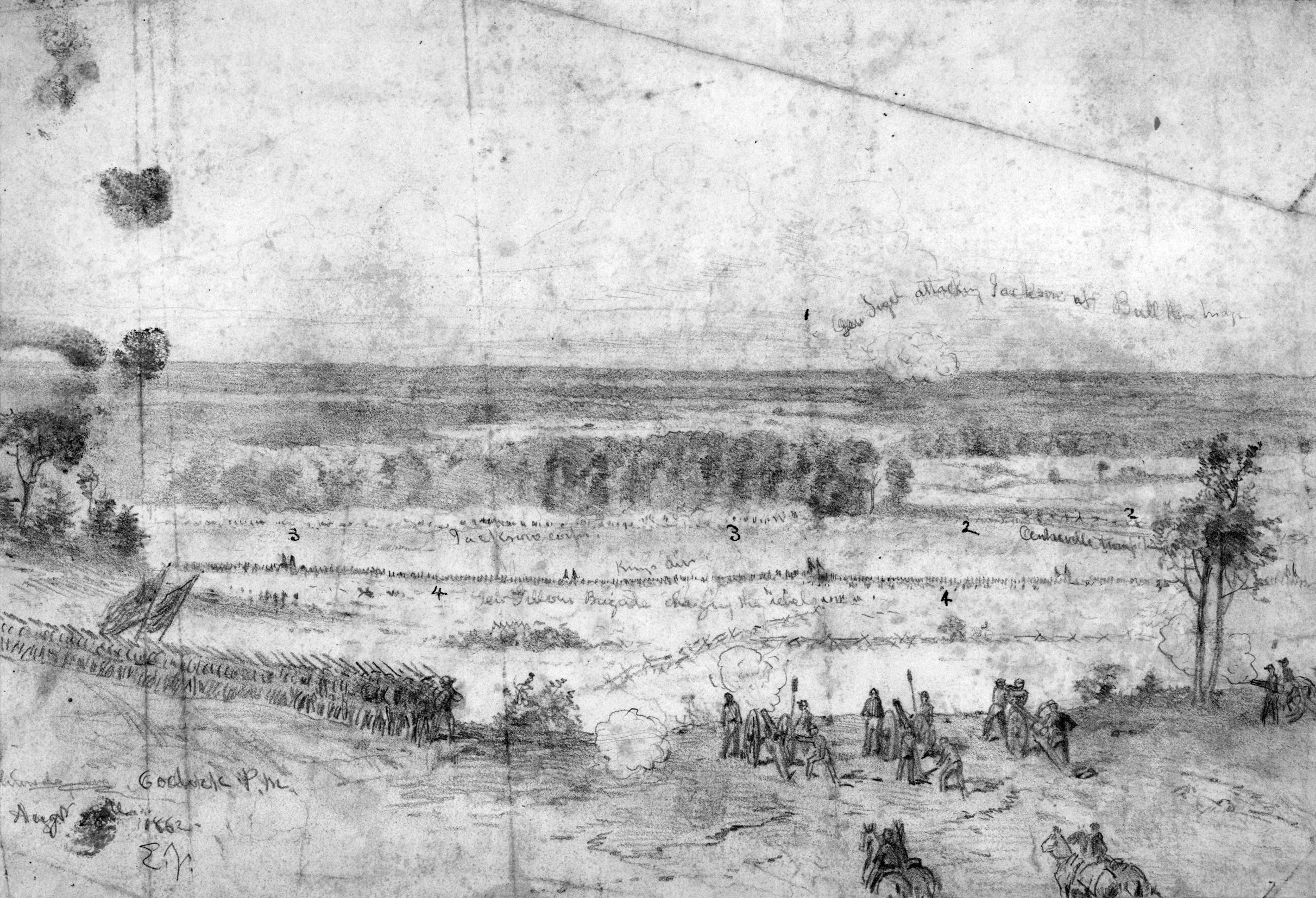

King was commanding his division from an ambulance after suffering a severe epileptic seizure on August 23. Now, as his mile-long column unknowingly neared the front of Jackson’s entire corps, with Brig. Gen. John Hatch’s brigade in the lead, King suffered another mild seizure that rendered him combat ineffective and left his division without a commander for the remainder of the evening. At 6 pm, after Hatch’s brigade marched through Groveton past the Brawner and Dogan farms north of the pike, his men approached a knoll east of the village and spotted movement on the ridge to the north. With Hatch now in temporary command of the division, the blue column halted while the 14th Brooklyn was brought up to reconnoiter the woods and fields below the ridgeline. Finding nothing, they fell back to the pike.

As Hatch and the other brigade commanders—Gibbon and Brig. Gens. Abner Doubleday and Marsena Patrick—scanned the ridgeline with field glasses, a lone Confederate horse-drawn battery emerged from the trees and wheeled into position. Captain Aston Gerber’s Staunton Artillery promptly opened up on the Union column; their third discharge found the range and began targeting Gibbon’s brigade and the two brigades behind him, strung out along the pike.

As shells screamed overhead and exploded around them, some of the Union column quickly scattered, their ambulances and wagons careening panic-stricken off the road into the fields and forests south of the pike. The New York regiments in Patrick’s brigade, now about 1,000 yards behind Gibbon, immediately broke up and headed for the trees—they would not participate in the fight to come despite Gibbon’s repeated pleas for help. It would be hours before Patrick could regain control of his troops, leaving Gibbon and Doubleday to contend with the Confederates by themselves. (Hatch had marched his lead brigade farther east along the turnpike, putting himself out of the fighting and almost out of range of Confederate cannons.)

With his brigade posted on the road a quarter mile behind Hatch’s, Gibbon rode to a knoll north of the pike and watched as two additional Confederate batteries emerged from the tree line, unlimbered, and opened fire on the broken Union column on the road below. Keeping his head like the veteran he was, Gibbon shouted for his old battery, Battery B of the 4th U.S. Artillery, to deploy on a small knoll east of the Brawner farmhouse. Soon the ground trembled violently as Union and Confederate gunners exchanged fire. Within minutes, the Union regulars were getting the better of it and the Southerners elected to pull their guns back to safety. Just as the guns fell back, Jackson sent in another battery, on Gibbon’s left, and it began blasting case and solid shot at the Union battery. Doubleday’s lead regiment, the 76th New York, was hit hard and began to panic; its commander, Colonel William Wainwright, succeeded in calming his jittery troops.

Gibbon quickly ordered his entire brigade off the road and north into the cover of the trees on the Brawner farm, followed by Doubleday’s entire brigade. At this moment, Gibbon could only assume that this was merely harassing fire from a few light horse batteries. He had no idea that Jackson’s entire force of almost 24,000 men lay just beyond the trees within a mile of his position. Doubleday found Gibbon, and the two brigadiers agreed that since Jackson’s main force was reported to be at Centreville, the artillery to their front must be that of Stuart’s Confederate horse artillery. Gibbon quickly assented to Doubleday’s suggestion that an attack on the closest enemy battery was called for. Those members of the Black Hat Brigade who had yet to experience combat were about to about to receive their baptism of fire.

Gibbon ordered Colonel Edgar O’Connor, commanding the 2nd Wisconsin, to advance his regiment and capture one of Stuart’s guns. The Badgers moved through the woods onto open ground and formed into line of battle, pushing out skirmishers and finally halting in a broom sedge field near the southern end of the ridge, 300 yards from the Brawner farm. To their front and left lay a log farmhouse, a barn, several outbuildings, and a peach and apple orchard.

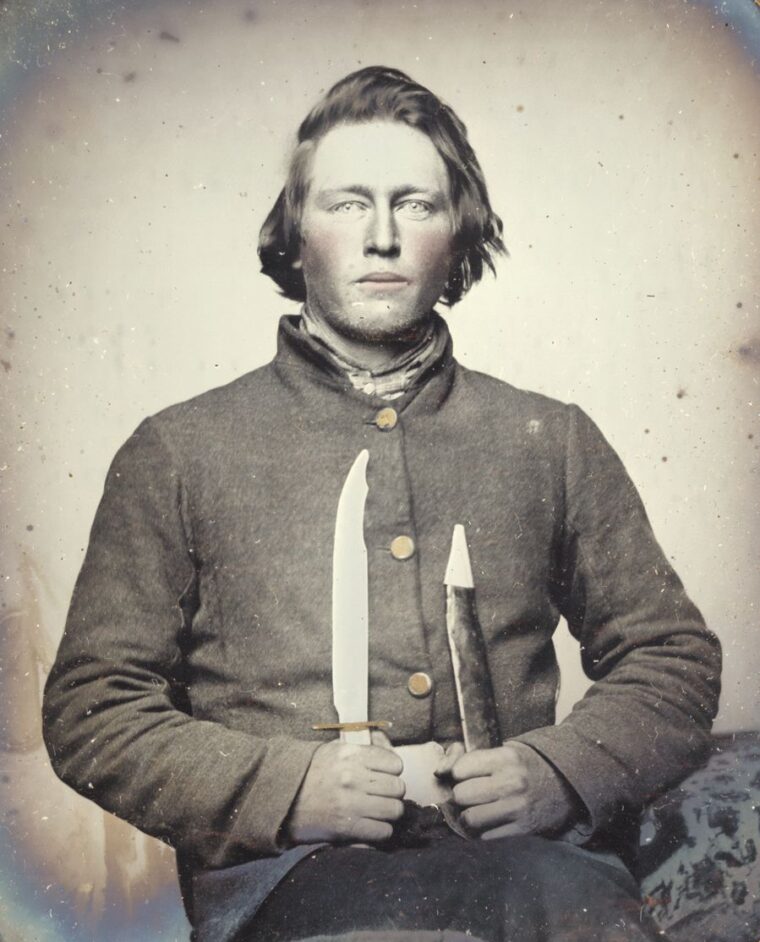

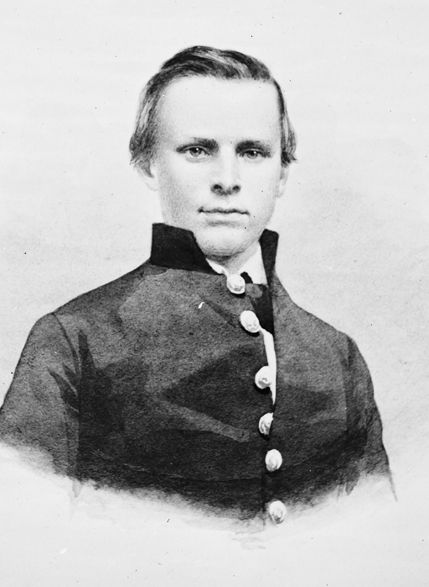

Suddenly, a long line of Confederate infantry columns emerged from the woods to their right and a bit farther up the hill, five scarlet battle flags waving proudly, one for each Virginia regiment marching forward. It was the storied Stonewall Brigade, the flower of the Confederate Army. Called “Jackson’s foot cavalry” because of the incredible distances they could travel in mere days, they were arguably the best soldiers in Lee’s army. Veterans of every major battle fought in the East, Jackson’s men had suffered heavy losses in the Seven Days and Shenandoah campaigns, cutting their numbers from 2,000 to 800. But this 800, commanded by Colonel William Baylor, were tough, seasoned, hard fighters and outnumbered Gibbon’s Badgers by almost 2 to 1. Soon, Gibbon’s troops found themselves under musket fire from the advancing Confederates.

Although the sight of Jackson’s veterans sent a ripple of awe through Gibbon’s line, the Wisconsin men weren’t deterred and continued moving up the hill toward the enemy. Other than a few wild volleys that endangered the Union skirmishers more than it did the Confederates, the 450 men of 2nd Wisconsin held their fire. As the two groups closed to musket range, one young Union soldier noted that his comrades “held their pieces with a tighter grasp” and began to murmur quietly, “Come on, God damn you.” At less than 100 yards, the 2nd Wisconsin unleashed what a Confederate officer remembered as “a most terrific and deadly fire.” The Virginians staggered and came to a halt in the face of the Union volley.

The Confederate column pushed forward to an old fence 80 yards from the blue line, halted, and opened fire themselves, letting loose with the fearsome Rebel yell. “Within one minute, all was enveloped in smoke,” wrote one Union survivor, “and a sheet of flame seemed to go out from each side to the other along the whole length of the line.” For 20 minutes the two lines blazed away as casualties began to mount. O’Connor was knocked from his horse by musket fire and died within the hour.

Soon the Confederate numbers began to tell, as 4th Virginia gained the fences and outbuildings around the Brawner home, threatening to overlap the Badgers’ left flank. Gibbon ordered Colonel Solomon Meredith’s 19th Indiana, 423 men strong, to move up on the Badgers’ flank east of the Brawner home. As the inexperienced Hoosiers moved into position, they came under a murderous volley from 4th Virginia. Somehow they steadied themselves and began to fire back as rapidly as the more experienced Wisconsin men next to them.

With the initial advance by the Stonewall Brigade stalled and the daylight beginning to fade, Jackson attempted to bring additional units into the fray. The closest troops available were three or four regiments of Brig. Gen. Alexander Lawton’s brigade. Ignoring the chain of command, the impatient Jackson personally led some 900 Georgia troops across 400 yards of open ground into a blaze of fire from Federal muskets. They took up positions on Baylor’s left, overlapping the 2nd Wisconsin’s right flank, which they targeted with massed volleys. Responding to Lawton’s advance, Gibbon hurried forward Colonel William Robinson’s 7th Wisconsin, and the men of the 440-strong regiment cleared Brawner’s Woods and aligned themselves on the Union right, sighting Lawton’s Confederates less than 100 yards to their front.

The two lines stood and blasted away, with casualties mounting on both sides. Union wounded began to steadily stream down the hillside toward field hospitals south of the turnpike. As it became darker, the rifle fire merged into what Gibbon described as “a long and continuous roll.” In his ambulance south of the pike, King wrote that, as the dim twilight deepened, “night and hell seem to come down together.”

As the brutal fighting continued, Jackson became uncharacteristically desperate. The Union troops were fighting with what he described later as “obstinate determination,” and Jackson was not a man given to hyperbole. He tried to get more men into the line to break the Union front once and for all. He dispatched Trimble’s 1,200-man brigade to form up on the Stonewall Brigade’s left, hoping to envelop Gibbon’s line and turn the Union flank. However, as Trimble’s men approached their place in the Confederate line, they discovered that Gibbon was ahead of Jackson. Gibbon had sent his last regiment, Colonel Lysander Cutler’s 6th Wisconsin, forward into a dry streambed, lengthening the Union line to the right. As Cutler’s green troops moved up the slope, they could clearly see, even as darkness approached, their 2nd and 7th Wisconsin comrades on higher ground to their left. They were, as a Union survivor remembered, “seemingly under the concentrated fire of at least six times their own numbers.”

As Cutler’s men fell into line, he ordered them to halt, dress their ranks, and open fire; a sheet of flame from 500 muskets erupted. At a range of only 75 yards, the Union volley brought the Southerners to a complete and utterly stunned halt. One Union survivor from 6th Wisconsin recalled, “Every gun cracked at once, and the line in front, which had faced us as the command ‘ready’ melted away, and instead of the heavy line of battle that was there before our volley, they presented the appearance of a skirmish line.” Trimble’s troops were veterans and doggedly continued their advance, seeking cover behind an old snake-rail fence, and were soon firing back. For 90 minutes, the two lines exchanged murderous volleys as the light grew dimmer and dimmer.

When he discovered a 250-yard gap in his line between 7th Wisconsin’s right and the left of the 6th, Gibbon appealed to Hatch, Doubleday, and Patrick for help. Tied down under heavy Confederate artillery fire, Hatch managed to send one regiment to support Gibbon’s artillery units. Patrick preferred to hold in place. As far as he was concerned, Gibbon, the son of a slaveholder from North Carolina, with three brothers, two brothers-in-law, and a cousin serving the Confederacy, had gotten himself into this scrape and he would have to get himself out of it.

Doubleday unilaterally ordered forward the 450-man 76th New York and the 531 men of 56th Pennsylvania to aid Gibbon. Almost 1,000 fresh troops moved into the gap, stiffening Gibbon’s battered line as well as completing it. The Union line now stretched for nearly half a mile, with six regiments—2,781 men—engaged. On the other side, Jackson had committed three brigades against Gibbon and Doubleday and now had more than 3,000 men engaged. Although he had over 20,000 troops in the area, he was having difficulty bringing more troops to bear. Darkness was less than an hour away. On the Union left, 19th Indiana and 2nd Wisconsin continued to battle the Stonewall Brigade. In the smoke and dust on the Union right, 6th Wisconsin and Trimble’s men fired blindly at each other’s muzzle flashes, the lines remaining locked in pitched battle.

Refusing to accept a stalemate, at 7:15 pm Jackson ordered Brig. Gen. William Taliaferro to dispatch a fresh brigade against 19th Indiana on the Union left. Taliaferro’s nearest uncommitted brigade, that of his uncle Colonel A.G. Taliaferro, was more than a quarter mile away and would take some time to arrive. Jackson ordered a frontal assault by the combined forces of Lawton and Trimble to advance and crush all resistance. Only one unit, Trimble’s brigade, was able to respond immediately.

Due to a deadly lapse in communications that seemingly plagued the Confederates for the entire day, only two of Trimble’s four regiments got the order to advance, and they went forward together, unsupported and with their flanks hanging in the air. Trimble’s 21st Georgia and 21st North Carolina received a devastating volley from 56th Pennsylvania to their front, while the 6th Wisconsin poured musket fire into the Confederate left. Within seconds the attacking line seemed to melt into the ground, withered by the storm of lead loosed upon it. One 6th Wisconsin officer remembered, “Human nature could not stand such a terrible wasting fire. It literally mowed out great gaps in the line.”

As Trimble’s assault ground to a complete halt, Jackson rode to Lawton, whose brigade of Georgians was now near the center of the Confederate line, and ordered him forward. Once again only two regiments—the 26th and 28th Georgia—responded, and they met a fate similar to Trimble’s, as 7th Wisconsin and 76th New York wheeled from their positions to deliver a crushing volley into the Southern flank. “Our fire perfectly annihilated the rebels,” one soldier in the 7th Wisconsin reported. A 76th New Yorker added, “No rebel of that column who escaped death will ever forget that volley. It seemed like one gun.” The 26th Georgia suffered 74 percent casualties in the assault, leaving their colors on the field. The survivors fell back to their original positions. Nothing came of the Confederate advance, but both sides battled on, neither advancing nor retreating.

The final act in the bloody drama came on the Federal left where Gibbon, realizing the tactical importance of 19th Indiana’s position, had stationed himself for the duration of the fighting. Confederate artilleryman Captain John Pelham hurried three rifled guns from the rear and managed to get two of them unlimbered within 100 yards of the 19th’s line. Seeing this, Colonel Meredith, known as “Long Sol” to his troops for his six-foot, seven-inch height, moved two companies to his left and forward, where their fire forced Pelham to move his guns back. Meredith himself was severely wounded when his horse was shot and fell on top of him. Behind Pelham came three of the five regiments of the brigade commanded by Taliaferro’s uncle, some 600 Virginians and Georgians, the last of Jackson’s immediate reinforcements in that sector.

The fresh troops halted in the yard of the now-riddled Brawner home and raked the left of the Union line as almost full darkness shrouded the field. “The most terrific musketry fire I have ever listened to rolled along those two lines of battle,” Gibbon recalled later, “neither side yielding a foot.” At last, after Pelham’s guns found the range from their new position, adding to the rain of musket fire, Gibbon ordered 19th Indiana to conduct a fighting retreat. After almost two hour of continuous, close-range fighting and heavy losses on both sides, darkness and fatigue finally slowed the firing and the battle ground to a halt sometime after 8 pm.

When it was over, both sides had suffered heavily—one of every three men to enter the battle was killed or wounded—but neither could claim a tactical victory. Jackson had not communicated well with his division commanders, resulting in piecemeal frontal attacks that were met by determined opposition from six Union regiments. Jackson commanded 14 brigades but was able to get only three seriously engaged, fielding two understrength brigades—Baylor’s and Trimble’s—and regiments of two other brigades commanded by Lawton and A.G. Taliaferro. After Taliaferro’s 600 men entered the fray, the total strength of the Confederate assault force outnumbered the Union’s six regiments by about 800 men. Jackson lost two of his three division commanders—a Minie bullet shattered Ewell’s leg and Taliaferro was wounded three times and put out of action—and Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill’s reinforcements arrived too late to take part.

As the field hospitals quickly filled and surgeons began their grim work, the dreadful losses on both sides became apparent. The first units to enter the fray suffered terribly: the 2nd Wisconsin went into battle with 430 men and counted 276 casualties, including 83 men killed outright, while the Stonewall Brigade suffered 300 casualties, almost 40 percent of its strength. The 19th Indiana suffered heavy losses as well, around 60 percent, with 260 casualties out of 423 men. Lawton’s Confederate brigade lost more than 300 men killed, wounded, and missing, while in little more than an hour of fighting, Trimble’s brigade suffered some 350 casualties, almost a third of its strength. Trimble’s 21st Georgia lost 184 men out of 242, the second worst Confederate regimental loss in the entire war, second only to 1st Texas at the Battle of Antietam.

As a whole, Gibbon’s brigade lost almost 40 percent of its strength—725 casualties out of 1,900 troops engaged. Doubleday’s two regiments suffered another 425 casualties, bringing the Federal total to 1,150. Jackson’s force of 3,500 suffered 1,100 casualties.

King reassumed command at about 11 pm, and after conferring with his brigade commanders he decided to march his battered division to Manassas Junction, eight miles away. The division of Brig. Gen. James Ricketts joined him on the road, retreating from Thoroughfare Gap after a brief encounter with Longstreet’s Confederate wing as the latter was making its way to the battlefield.

All things considered, Brawner’s Farm was not one of Stonewall Jackson’s shining moments. Although fully invested and present on the battlefield, he had been unable to win a tactical victory over an isolated, ostensibly outnumbered Union division fighting without a commander. Over the course of the fighting, Jackson’s various units failed to deliver sufficient numbers to overwhelm, or even breach, the Union line. Taliaferro was slow getting his division to the front—out of four brigades, only one full brigade and part of another saw action—and Ewell failed to deliver his two available brigades with cohesion, ensuring piecemeal attacks and forcing Jackson to intervene personally, something a major general should never have to do. Both Ewell and Taliaferro were seriously wounded during the battle, further adding to the command problems the Confederates faced.

John Gibbon, on the other hand, could take away a measure of pride in his performance and that of his largely untested men. After the Battle of Brawner’s Farm, the members of the Black Hat Brigade could truly say that they had “been to see the elephant,” as Civil War soldiers called the experience of combat. They had lived—some of them, anyway—to fight another day, but though they were “always ready for battle,” as one of them noted, after Brawner’s Farm they were “no longer eager for it.” Spoken like a true veteran.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments