By Charles Whiting

In the early hours of Sunday morning, December 17, 1944, an American brigadier general suffering from piles was heading into the unknown. That gray dawn, with the guns rumbling to the east, the newly promoted general was being driven in a looted Mercedes to a Belgian town located a couple of miles from the border with Nazi Germany.

Behind the general in his Mercedes, which required the combined efforts of driver and himself to change gear, there came a lone jeep. In it the frightened GI driver constituted his sole bodyguard in this tense, rugged countryside between Bastogne and the other major Belgian road-and-rail center of St. Vith, the general’s destination.

General Bruce Clark, a big, rugged man in his mid-30s who tended to run to fat if he were not careful, had been trained at West Point to become an engineer. Due to wartime circumstances, however, he had first gone into action four months before as a combat commander in General George S. Patton’s favorite armored division, the 4th Armored. There he had proved that he knew how to manage tanks just as well as he knew how to construct bridges.

Unfortunately, that did not bring him the kind of promotion he eagerly sought. Once, during a visit, Patton told him why. “You’re a damned nobody, Clarke,” he had exploded. Clarke, who had been born to a large and poor family in a tight apartment above a grocer’s shop, had asked why. Patton explained that General George Marshall, the U.S. Army’s chief of staff, had never even heard of Clarke. “Hell, Clarke,” Patton had said in that curiously high-pitched voice of his, “if you had been in the infantry instead of an engineer and had served in Fort Benning you would have been a major general by now.”

In prewar days when General Marshall had been in command at Fort Benning, he had always noted the names of officers who could be promoted rapidly in the case of war.

Now, Clarke, newly promoted and transferred to the 7th Armored Division as a combat commander, was on his way, without Marshall’s aid, to his own personal date with destiny. Ambitious, and not a little ruthless, Clarke would start a reputation at this little border town of St. Vith, where so many other senior U.S. officers would have theirs destroyed, that would carry him to the highest echelons of the U.S. Army and make him a trusted military adviser to a series of U.S. presidents.

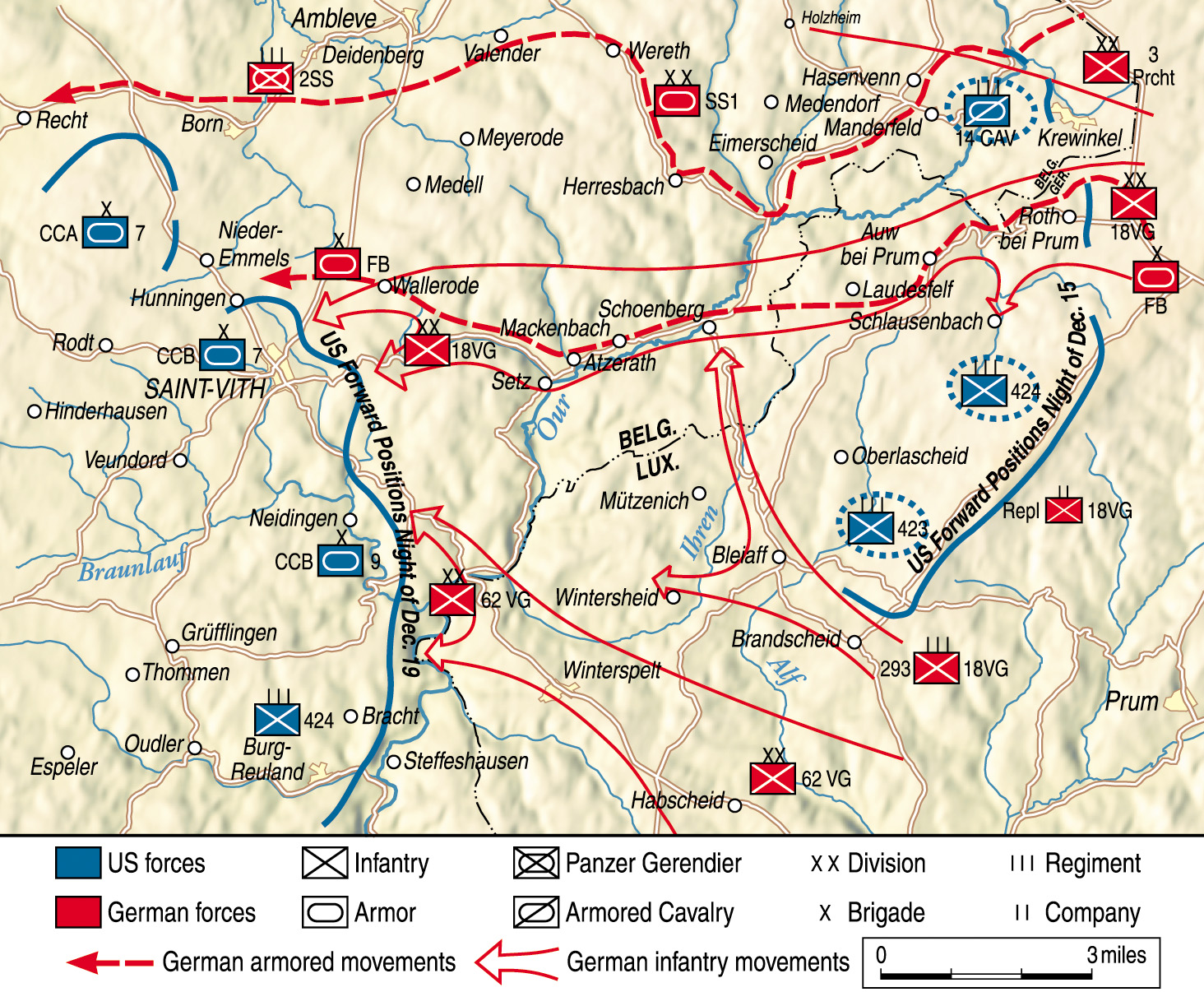

For Clarke was heading for a military SNAFU that would have frightened off many more senior officers this dawn. The day before, a whole German Army, the 5th Panzer, commanded by dynamic little gentleman jockey General Hasso von Manteuffel, had struck the 60,000-strong U.S. VIII Corps with disastrous results. The U.S. 106th Infantry Division, the newest U.S. division in Europe, had been trapped and was now virtually surrounded in the Eifel Mountains just across the border in Germany. Its neighbor, the 28th Infantry Division, had been split in half with one of its decimated regiments, the 110th, pulling back in great disorder. In essence, VIII Corps, a mixture of unblooded infantry divisions and those that had suffered appalling casualties in the previous November, was on the verge of collapse. Once von Manteuffel’s armor made a complete breakthrough, the fate of the corps might well be sealed.

That Sunday, Clarke did not know that. All he knew was that there was a flap at the front and that he was to lend a hand with his combat command of two columns strung out somewhere far behind, heading down from Holland to Belgium along roads already being ambushed by the advancing Germans. Perhaps it was good that Clarke did not know just how bad the situation was, for as he explained much later, “I was being thrown into a situation the like of which I had never known up to then and fortunately never have since.”

Arriving with his three-man team in St. Vith, Clarke’s driver fought his way through the clogged streets, where panic reigned in all its naked ugliness, and Clarke painfully got out of the Mercedes to report to Maj. Gen. Alan W. Jones, the commander of the Golden Lions, as the men of the 106th Infantry Division called themselves after their divisional patch. He climbed the stairs of the Klosterschule, Jones’s headquarters, where Jones was located on the upper floor, trying to spot the first Germans the staff expected to appear from the wooded valley below.

Jones, heavy set with sleek, black hair and a pencil-slim moustache in the fashion of the matinee idol of the day, Don Ameche, had been in the Army since 1917, but had never heard a shot fired in anger. Now, within five days of arriving at the front, it appeared he had lost two regiments in a German trap while his third was fighting its way back across the German frontier to avoid a similar fate.

At first, Clarke did not quite know what to make of the older major general, who seemed to waver between an unreal pugnaciousness and a certain careless indecisiveness. “They’ll never take me alive,” he told Clarke, saying that he always kept a grenade in his jeep in case he was ever trapped by the “Krauts.” At the same time, he seemed to think that since Clarke had arrived with his three men he was saved. He could leave everything to the 7th Armored. As General Clarke noted to this author, “General Jones was surprised and not alert to the danger presented by the Germans.” To his cronies and fellow veterans of the battle, Clarke expressed his opinion of Jones, his temporary superior, in a much more drastic and outspoken manner. But that utterance is better not appearing in print.

Still, that morning Clarke listened attentively as Jones explained what he knew of the situation. So far Jones had asked for an air strike. It would never come due to bad weather. He had also organized a stop line to the east of St. Vith under the command of former football player and now engineer Lt. Col. Thomas J. Riggs, Jr. His 500-man-strong engineer battalion was Jones’s only reserve. Otherwise, Jones seemed to have lost control of his three infantry regiments. Indeed, he was being forced to communicate with them, when he did, through corps headquarters in Bastogne. Now, as Jones expressed it to Clarke, “everything depends on your CCB.”

Clarke promised that as soon as his men arrived he would send them to the aid of the two trapped Golden Lion regiments in the Eifel. Then, unable to do much else but wait, he thought he would help to clean up the clogged streets of the German-speaking border town before his command arrived. He did not have a clue when that might be.

To Major Don Boyer of Clarke’s command, it seemed that day that CCB, 7th Armored Division, might never arrive—not because of direct enemy pressure, but because of the cowardice and panic of their own people. Just after his advance party had passed the hamlet of Poteau, for example, the already slow-moving convoy was forced to grind to a halt. The road ahead was clogged with U.S. traffic going the wrong way—to the rear. Angry already, Boyer pushed his way forward until he came to a group of Staghound armored cars commanded by an officer wearing the golden lion patch of the 106th.

“Who are you?” Boyer rasped. The officer told him. Boyer asked, “What’s the score then?” He should have known better. It was obvious the Golden Lion was panicked, as his next words revealed. “The Krauts—at least six panzer divisions—hit us yesterday,” the man quavered, his bottom lip trembling. Boyer, a veteran of the fighting in France, asked cynically, “What are you going to do about it then?” “Me, I’m leaving.” Without another word the frightened Golden Lion got back into his vehicle and vanished, leaving a fuming Boyer standing.

Ten miles or so away, Clarke was faced by a similar situation. He had left his aid, Captain Junior Woodruff, at the junction of St. Vith’s Hauptstrasse and the Malmedy Strasse, the direction from which the 7th’s relief column would come. But the key road was packed with fleeing vehicles, anything and everything from 8-inch howitzers to jeeps. Clarke, who had a short fuse cried, “What happened, Woody? How come you’re letting them through?” He was referring to the fleeing vehicles. An unhappy Woodruff replied and pointed to an officer, “General, that lieutenant colonel—he was going to use the road. He said he’d shoot me if I got in the way.”

That did it. Clarke strode over to the artillery colonel and yelled above the racket, “Get the tractors off the road so my tanks can get through. If there’s any shooting to be done around here, I’ll do it!” He tapped his pistol holster. The artillery colonel backed off. The road from Malmedy was cleared, but there was still no sign of Clarke’s tanks. So, as Clarke phrased it later, “I became the highest ranking traffic cop in the U.S. Army for a while.” He started directing the traffic himself.

By late afternoon that terrible day, the first of Clarke’s combat command arrived. They came in dribs and drabs. Some had horrific tales to tell about what had happened on the trip from Holland. Clarke had no time to listen. Standing there doing his traffic cop bit, he assigned them personally to their positions as they arrived. Already, he knew he did not have sufficient strength to help Jones’s trapped regiments. By now two of them were cut off in an area of 10 square miles of rugged, wooded country some miles away from St. Vith. There, six battalions of green infantry, supported by three artillery battalions, were crowded together in some confusion with their supplies running low, under senior officers who could not seem to make up their minds on what to do next: stand and fight or retreat into Belgium. Like predatory gray wolves, the Germans were heading for their unsuspecting prey in St. Vith.

By Monday, December 18, Jones gave in. He had lost control of his division, and it seemed Clarke was not prepared or in any position to rescue his Golden Lions. Late that afternoon he ordered his command post to move back to Vielsalm some 20 miles to the rear, where Clarke’s boss, Brig. Gen. Robert W. Hasbrouck, was in charge. Now it was up to Clarke.

That fact did not particularly please Clarke. By now he knew the Germans were bypassing him on both flanks, and from the reports of officers coming up from corps headquarters in the Bastogne, the rear was devoid of U.S. troops save those fleeing toward the River Meuse. And the Krauts were increasing their pressure all the time.

It was understandable. Manteuffel had wanted St. Vith and its communication network the first day. Now he was two days behind schedule, and everyone from Hitler downward was pressuring him to capture the border town so that the tanks could roll for their first major objective, the Meuse.

Clarke was determined to do his duty. He had formed a kind of rough and ready horseshoe of defense around St. Vith, using what infantry he had and his armor. The task was difficult. The U.S. training manuals had little to say about using tanks in defense. In street-to-street fighting they were particularly vulnerable to some brave enemy infantryman equipped with a rocket launcher—and the Germans had plenty of those. Still, using his Shermans was the only way Clarke knew to thicken his line, and he used them, praying that the weather would not change.

As long as the biting wind that seemed to come straight from Siberia froze the ground, his 30-ton steel monsters would be alright. But once the countryside thawed around the embattled town, the Shermans would be bogged down. Then it would be anybody’s guess what might happen. His tanks would be sitting ducks. Naturally, he thought of retreating. He had some 22,000 men under command, and he knew very few of their officers. Still they were American soldiers and his responsibility. Could he simply sacrifice them in what was becoming increasingly a one-sided battle?

The powers-that-be seemed to have forgotten Clarke. His Army commander, General Courtney Hodges of 1st Army, had seemingly vanished from the face of the earth. As for General Troy Middleton, commanding VIII Corps, he had lost two of his four divisions and the other two were either split up and, in the case of the veteran 4th Infantry Division, now under heavy attack. In essence, Middleton was losing control rapidly, and although Clarke did not know it that day, the portly, bespectacled general, who had been called from retirement to take up his command, was now preparing to move his headquarters from Bastogne. It was clear, even to Clarke with his limited information, that Middleton expected Bastogne soon to be under attack. What would happen to St. Vith then? Where could he retreat to?

Of course, the decision to fight or withdraw placed Clarke, a relatively junior general as we have seen, in a great quandary. He knew the U.S. Army’s doctrine as once expressed by General Omar Bradley, who was also confined to his headquarters in Luxembourg City, cut off from most of his Army group and fearing for his life at the hands of German murder squads.

“The US Army does not give up ground,” Bradley had maintained, “bought with American blood.” Now, if he, Clarke, did so, he guessed that his career in the U.S. Army might come to an abrupt end. Bradley was well known for his habit of abruptly sacking generals whom he thought had failed him. That third week of December, with Christmas just around the corner, Clarke must have clearly wished for some senior officer to appear at St. Vith and solve his problem. But that particular Christmas present wasn’t going to be his—yet.

That day, Clarke received a message from 7th Armored’s G-4, a Colonel Hoggeson. He signaled, “I have no contact with Corps … but Corps has ordered us to hold … Hope you don’t think I’m crazy. CG was well pleased with everything you have done. Congrats. Don’t move ’till you hear from me.” That message made up Clarke’s mind for him. The “Corps” in question was the XVIII Airborne, commanded by General Matthew Ridgway, a veteran of Sicily, Italy, and the battles in Holland and Normandy. Ridgway was a parachutist. He would expect Clarke to stand, even if he were surrounded by the enemy. Paratroopers were taught to do so. But he knew nothing of the situation in the St. Vith area. Yet, Hasbrouck would have to concede to Ridgway’s wishes if he did not wish to be relieved himself.

Things were already changing drastically on the northern shoulder of the Bulge. Secretly and unofficially at first, Montgomery had taken over command of all troops in the area, including Ridgway’s corps and with it Clarke’s command. Montgomery was a commander who was not particularly interested in ground as such; men were more important to him. Now, Montgomery took a hand in the fate of Clarke of St. Vith.

On the morning of Wednesday, December 20, Montgomery strode into Hodges’s new headquarters in Chateaufontaine, where the lst Army commander had moved in haste, leaving all his top secret documents to be examined by anyone who cared to wander into his abandoned headquarters at Spa. Before he had left his own headquarters, Montgomery had told his staff he could not believe that two U.S. divisions (the 106th and 28th) could have been overwhelmed in such a short time. He was going to send out his scouts to find them and, if successful, to explain the situation and to request the commanders concerned to withdraw westward to positions where they could link up with other U.S. divisions.

Now, Montgomery told a broken Hodges, who had lost control of his army and had still to make an appearance at the front to find out personally what had happened to his VIII Corps, “We must sort out the battlefield, tidy up the lines,.… The primary job is to pull everyone out of the great St. Vith pocket.” Montgomery, the man who had been wounded and left for dead on the battlefield, was not going to waste good men’s lives that easily.

Hodges did not like that, and for a time Montgomery humored him. But not for much longer. That day, unknown to Clarke, Montgomery was making decisions that would save him and his 22,000 GIs at St. Vith. As Clarke’s son, Bruce Clarke, Jr., once told this author, “Dad once drew a list of people involved in the period 16–24 December 1944 and gave them yes or no ratings, depending, in his view, how effectively they had dealt with the situations that had confronted them at that time. Yes rating went to Montgomery, Hasbrouck and Hoge (General Brigadier General William M. Hoge of the 9th Armored Division). No rating went to Ridgeway, Middleton and Jones.”

Clarke was not out of the woods yet. There were still the Germans and the weather to be reckoned with. All along the perimeter of Clarke’s defensive position, which became known as the fortified goose egg, his weary men could hear the rumble of German armor and the creak and jingle of horse-drawn transport heading west for the Meuse. Signal flares shot into the dawn air constantly. Close by their positions in the woods, they could clearly make out the cries of German NCOs. The American defenders were not allowed to fire back. They were running out of ammunition fast; every bullet and shell had to count. The Germans had plenty of ammunition. Shortly after first light, German infantry attacked in small groups. Clad in white camouflage overalls, they advanced under a mortar bombardment behind their tanks. They were obviously looking for a weak spot in the goose egg.

As the intrepid Major Boyer recalled long afterward, “The Krauts kept boring in as fast as we decimated their assault squads. Again and again, the Krauts got close enough to heave a grenade at a machine gun crew. One .50-caliber squad, which had been dishing out a deadly hail of fire, was hit by a panzerfaust. The gunner fell forward with his face torn off, the loader had his arm torn off at the shoulder and was practically decapitated, while the gun commander was tossed about 15 feet away from the gun to lie there quite still.” That night, things got even worse, and Boyer watched in horror as German tanks knocked out five Shermans one after the other, while he took cover in a snow-filled ditch, hoping not to be discovered too.

By this time, an exhausted Clarke, who had been without sleep for days now, had only about 100 infantrymen left in the St. Vith area. All his tank destroyers had been knocked out, and in his own immediate command post area he had exactly four tanks left under Lieutenant Will Rogers, Jr., the son of the famed homespun American humorist. The younger Will Rogers, a bit of a joker himself, had nothing to laugh about this day.

Clarke decided to shorten his line, so his men stole back in fours and fives. The unlucky Boyer was captured doing so. His captor smiled at him. “Just the fortunes of war,” the German officer told his bespectacled captive. “Maybe I’ll be a prisoner tomorrow”. Boyer was too exhausted and miserable to reply. That night, Clarke commented to Hoge, “It looks like Custer’s last stand to me.” However, help was on its way at last.

That Friday, Montgomery finally made his decision. Earlier that day, Ridgway had told Hasbrouck he might still be able to hold. Pointing to the fortified goose egg on his big situation map, he snapped, “What do you think of making a stand inside this area? You’d hold out until a counterattack catches up with you. You’ll soon be surrounded of course, but we’ll supply you by air.”

Hasbrouck did not like it and he said so. “The area is heavily wooded with only a few poor roads. Besides, the troops have had over five days of continuous fighting…. My people are only 50 percent effective.… I’m sure that goes for the infantry too.”

Jones, the failure, who was present, suddenly chimed in to say, “I think it can be done.” That made Hasbrouck even angrier. Even as Ridgway was being told by Clarke’s individual commanders that their troops were only 50 percent effective (Clarke told him bluntly that his were only 40 percent), Montgomery overruled Ridgway on the decision to stand and made a lifelong enemy. He passed on a message to Clarke through Hasbrouck, which read, “You have accomplished a mission, a mission well done. It is time to withdraw.”

However, that was easier said than done. A thaw had set in, and Clarke’s vehicles were bogged down in the new mud. That day, Hoge told him, “Bruce, let’s just stay and fight. Our vehicles are up to the hubs. We haven’t got a chance of getting out.”

Clarke frowned and got on the radio to Hasbrouck in Vielsalm, his initial joy over the prospect of a withdrawal vanished. With a note of finality in his voice, he told his divisional commander, “We have to stay.” It looked as if there was no hope for him and his trapped men.

At five that Saturday morning, a very worried Hasbrouck called back to Clarke to inform him, “The situation is such on the west of the river (Salm), south of the 82nd, that if we don’t join them soon the opportunity will be over.” Clarke realized that that buck had been well and truly passed to him. The fate of all those thousands of young men lay in his hands. He ventured outside his headquarters. Dawn was not far off. Suddenly, he felt a thrill of recognition and a surge of new hope. The ground beneath his feet crackled and snapped. The many ruts made by his heavy vehicles had frozen!

Just then, an impatient Hasbrouck called him again from Vielsalm. “Bruce,” he demanded, “do you think you can get out?” For once the big general let his pent-up emotions ride loose. “A miracle’s happened!” he exploded. “The road’s frozen. We’re chopping the vehicles out of the ice—at zero six hundred we’re going to start rolling.”

It was not easy, and it took all day. Several times the Germans infiltrated the long lines of vehicles heading along a single road for Vielsalm. Impatient, Hasbrouck waited for them to arrive. Once he was nearly killed himself by a German tank that started to shell his position. Meanwhile, he reflected, he had once been faced with this same problem, a withdrawal under enemy pressure, at Fort Leavenworth’s staff college. His examiners had given him a bad mark on the paper because he had suggested troops should withdraw when under great pressure even by daylight.

Clarke had no such problems. Now it was up to the gods. He collapsed in the front seat of his jeep to snore his way out of the trap. Late that afternoon, Clarke staggered out of his jeep, swaying from side to side like a drunk. A doctor noticed his condition. “General,” he said, “you’d better get some sleep, or you could be in serious trouble.”

Clarke answered wearily that he did not think he could sleep. Too much was going on in his mind. “I can fix it,” the medic replied. He gave the big general a shot, which, as Clarke’s biographer put it, sent Clarke out “like a sack of sand.”

Twice, Ridgway’s aides tried to awaken the exhausted Clarke with, “General Ridgway wants you immediately.” Once, Clarke murmured in a highly drugged sleep, “The hell with it.” Later, when he had overcome his exhaustion, he was told once again he must report to the corps commander at once. He did so in the same dirty uniform he had been wearing ever since he had left Holland back on December 16. To his surprise, a granite-faced Ridgway did not offer Clarke a cigarette or a coffee. Instead he said, “I’m not used to brigadiers telling me that they won’t report.”

Clarke looked down at the airborne commander, “Well, general,” he said, “the fact is I hadn’t been to sleep for a week.” He explained what had happened and how the doctor had given him a knockout shot. Ridgway was not impressed. He started to lecture Clarke on Army discipline. Obviously, Ridgway was smarting at the way Montgomery had overruled him and ordered Clarke and his men out. Suddenly, Clarke had had enough. “General, I came to this command against my wishes. I got nine decorations for bravery in two days in my old outfit, I’ve got a good record in the Third Army and I can go back there tomorrow morning and General Patton will be glad to see me.”

Ridgway’s face remained stony. He did not react. Clarke tried again. “I’ve done my job up here. History will give our unit credit for the job we did at St. Vith. I’d like to leave.” Finally, Ridgeway responded. With a wave of his hand, he said, “Well, don’t let it happen again.”

In a way, that episode exemplified the fact that Clarke had reached the nadir of his career that wintry Saturday with the snow falling steadily outside. Within days of receiving his first general’s star, Clarke had fought a battle that had ended in a retreat and a kind of defeat as Ridgway saw it. Now all talk was of Bastogne and Patton’s brilliant counterattack. Few people considered the fact that General Anthony McAuliffe, in command of the 101st Airborne Division in the absence of General Maxwell Taylor, denied he had been surrounded and that he had needed Patton. America needed a victory. No one wanted to talk of the “defeat” at St. Vith, especially as the withdrawal from the Belgian town had been forced on the U.S. Army by Montgomery.

Just after Clarke had seen St. Vith retaken in January 1945 and celebrated the victory with toasted cheese sandwiches, he was sent back to England to recuperate and for another operation. He did not return to Europe until after the war was over to command the 7th Armored and later his old division, the 4th Armored. There is little information available on why it took so long. The Freedom of Information Act does not make it that easy to obtain the details, and there were many senior officers who had fought in that first week of the Bulge who were under investigation about their conduct.

When he did return, Clarke started to ascend the ladder of promotion steadily, becoming a corps commander, an acting Army commander, the commander of the U.S. 7th Army in Europe, and finally adviser to Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. He never forgot St. Vith, where it all started. In 1964, when there was a typhus epidemic in that part of Belgium and Americans were forbidden to go there, Clarke ignored the order and attended the reunion of the men who had fought there, many of whose lives he had saved.

There, too, he met an old enemy, General von Manteuffel. There, just outside Bruce Clarke’s old command post, the former gentleman jockey told the American who towered above him, “On Christmas Eve, I recommended that the German Army give up their attack and return to the West Wall. I gave as a reason the time my Fifth Army had lost at St. Vith. Hitler did not accept my recommendation.”

It was a bald, unadorned statement without flattery. But it told a pleased Clarke one thing. Despite critics such as Ridgway and other U.S. commanders in the Bulge, as a raw, young brigadier general unknown to the outside world, he had helped to change the face of World War II.

Well-known author Charles Whiting has written numerous books on topics related to World War II. He resides in England.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments