By James I. Marino

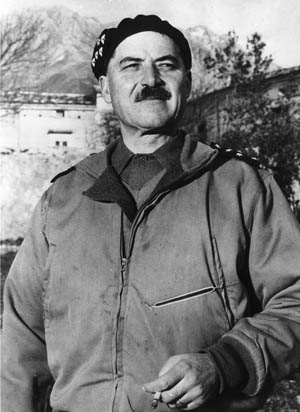

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme Allied commander in Europe during World War II, considered General Alfonse Juin to be the best French combat general of the conflict. Juin led the largest French command engaged against the Germans during the middle years of the war.

“He was one of the finest soldiers,” wrote General Mark Clark, commander of the Allied Fifth Army in Italy and Juin’s immediate superior officer. Although Juin outranked Clark, Juin accepted the lesser position because of his patriotism to France and the honor of leading the French forces against the Germans.

Born December 16, 1888, at Bone, French Algeria, Juin’s father was a policeman at Mostaganem. He enlisted in the French Army and entered Saint-Cyr, the French Military Academy, in 1909. He graduated 13th in his class in 1912, the same year as Charles de Gaulle, engendering a long friendship. Juin, posted to Morocco, joined the 1st Regiment of Algerian Tirailleurs and took part in pacification operations.

By 1914, Juin still commanded native Moroccan troops, but upon the outbreak of World War I he moved to the Western Front, as a lieutenant with the Moroccan Division. He took part in the Senlis, Ourcq, and Aisne offensives in 1914 and fought at the Battle of the Marne in September. He earned the Legion d’Honneur for “courage and power of decision.” Cited in dispatches five times and decorated on the field of battle, Juin was wounded twice, most seriously in 1915 at the Battle of Soissons on the Champagne Front. His right arm became almost useless, forcing him to salute with his left hand for the remainder of his career, officially permitted to do so by the French Army.

He remained in the hospital for eight months. In December 1915, promoted to captain, he took command of a company of Tirailleurs of the 5th Moroccan Infantry Battalion. He fought in the ill-fated Chemin des Dames Offensive in 1917. In February 1918, Juin was nominated for staff courses and assigned to headquarters. In October, he joined the French military mission as liaison officer with the American Expeditionary Force. His first contact with American command would provide beneficial experience during the next world war.

After the war, Juin taught at the Ecole de Guerre and graduated from the war college in 1921. He chose to return to North Africa, serving in Tunisia and Morocco. He took part in the Rif Campaign in 1923. He married Cécile Bonnefoy, had two sons, Pierre, a future St. Cyr graduate, and Michel, his youngest. Alphonse served in a Moroccan rifle regiment and later in a Foreign Legion Regiment. Juin relished cigars, bridge, music hall ditties, and dancing—but not the jitterbug. He relaxed by writing poetry and novels.

In the fall of 1925, Juin returned to France and became General Hubert Lyautey’s aide de camp on the Supreme War Council. Promoted to major in 1926, he transferred back to Africa the next year, joining the 7th Rifle Regiment in Constantine, Algeria. In 1929, he headed the Resident General, Lucien Saint, Military Council. He took charge of planning the 1929-1933 pacification campaign against the tribes in the Atlas Mountains. By 1931, he was appointed principal private secretary to now Maj. Gen. Lyautey at Rabat.

Promoted to lieutenant colonel in March 1932, Juin became a professor of general tactics in the Graduate School of War in 1933. He took command of the 3rd Regiment of Zouaves in Constantine on March 6, 1935. He was promoted to colonel in June. He returned to France, under Generals Philippe Pétain and Henri Giraud, where he became a member of the Higher War Council in Paris. In 1937, Juin was appointed chief of staff to General Charles Nogues in Morocco. After completion of courses at the Center for Advanced Military Studies, he was promoted to brigadier general on December 26, 1938.

Although in command of a brigade, Juin was assigned the key position of mobilization on the staff of the North African Theater of Operations. At the outbreak of war with Germany, Juin was promoted to general and took command of the 15th Motorized Infantry Division. When the Germans began their offensive against France and the Low Countries in May 1940, Juin moved the division into Belgium. Advancing 30 miles, the 15th Motorized Division engaged the German Sixth Army. Juin won the Battle of Gembloux in Belgium on May 15, but with the German breakthrough at Sedan, Juin retreated to Lille. He defended Valenciennes and covered the retreat of the French First Army. The division was encircled at Lille. After running out of ammunition Juin surrendered his command on May 30 and was imprisoned at Koenigstein Castle until June 1941. He was promoted to major general while in captivity.

Released at the behest of Marshal Pétain, the leader of the Vichy government, Juin was given command of French forces in North Africa. Appointed deputy commanding general of troops in Morocco, he replaced General Maxime Weygand as commander in chief of all North African troops on November 20, 1941. Juin was placed under the direct authority of Admiral Jean-François Darlan. In December 1941, Juin refused permission for the German Army to use ports, railroads, and roads in Tunisia but was overruled by Darlan.

Prior to and during Operation Torch, the Allied landings in North Africa, Juin served as an officer of the Vichy army; however, he demonstrated his sympathies for the Allied cause and ordered all French troops under his command in Algiers to lay down their weapons. Juin also worked to convince Darlan to order a cease-fire, eventually leading to an end to hostilities between the Allies and French forces in North Africa.

Juin and Giraud desired to form a united French army to help liberate France from the Axis, but they knew it would take time. First they had to form and train units into a cohesive force. The only reliable forces available were the five French divisions in Tunisia. The French XIX Corps, mostly Algerian Tirailleurs and Moroccan Spahis, occupied 35 miles of the front line along the Eastern Dorsal Mountains and eventually fought as part of the American army. Juin assisted American II Corps commander General Lloyd Fredendall in recovering his fortitude during the disastrous Battle of Kasserine Pass.

At the end of February 1943, Juin was promoted and removed from direct command of the XIX Corps. The general focused on the task of raising and training the French Army to be used on mainland Europe. On July 31, 1943, Juin received command of the French Expeditionary Corps (FEC). In November 1943, he was assigned as Resident-General of Tunisia.

Despite the demonstrated commitment of French forces in North Africa and the loss in Tunisia of 19,400 French casualties, more than half dead or missing, some Allied leaders, especially the British, viewed the French Army as suspect. Doubtful of the French Army’s quality and training, the plan for Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily, did not include the French.

Juin planned and led the successful French operation to occupy Corsica in September 1943.

Physically, Juin was sturdy at five feet, seven inches and 165 pounds. He was jovial, hard driving, and outspoken. In the field, he ate and slept very little. Though sociable, Juin liked to spend his first hour after waking in the morning in solitary thought and with a good smoke. Like most French generals, he had a flair for smart uniforms, preferred a Basque beret, and usually wore a cape, gloves, and boots. He spoke a heavily accented English.

General de Gaulle, who had known him since school, described Juin’s leadership style as “reserved and self-confident, isolating himself deep within his duties, deriving his authority less from apparent brilliance than from a profound and secret ability. Master of his craft, he drew up plans of maneuvers beforehand with a firm line. Basing his strategy on the material he received from intelligence, or from his own intuition, in every case the facts confirmed his procedure. He chose as a strategic axis a single idea, but clear enough to enlighten his men, complex enough to survive the pressures of action, strong enough to be imposed on the enemy.”

In December 1943, General Dwight Eisenhower, senior Allied commander in the Mediterranean Theater, officially requested that Juin and the FEC be sent to fight in Italy. First, Juin had to fend off an attempt by British General Harold Alexander to use the French units piecemeal and not as one command. Juin persuaded Alexander to allow his original two-division force to fight as a unified formation.

of muddy water. Juin stopped the Germans at Gembloux but was forced to retreat when the Germans

managed to break through at Sedan and elsewhere.

Juin agreed to subordinate the FEC to the command of General Mark Clark and the Allied Fifth Army for several reasons. The two generals had met during Operation Torch and become good friends. Juin understood the need to commit French forces sooner rather than later, and a corps that included three divisions was all France had available at the time. Waiting until a larger French army was formed might diminish the overall French contribution to Allied victory and fail to fully restore French honor. Most of all, Juin realized that politics dictated the highest level of cooperation with other Allied commanders.

French combat experience in the mountains of North Africa was priceless. Juin stressed his military doctrine of mobility on foot, infiltration, and small-unit autonomy, all invaluable attributes in the rugged terrain in Italy. French forces contributed substantially to the eventual breach of the Gustav Line near Monte Cassino and the drive into northern Italy in the spring of 1944.

Juin’s ability to analyze a tactical situation and make appropriate adjustments earned him great respect among his American and British contemporaries. De Gaulle wrote, “Juin restored the French military command to honor in the eyes of the nation, the Allies, and the enemy.”

By May 1944, Juin commanded 112,000 soldiers. The Expeditionary Corps consisted of the 1st Free French Motorized Division, 2nd Moroccan Infantry Division, 3rd Algerian Infantry Division, 4th Moroccan Mountain Division, 2nd and 6th Moroccan Infantry Regiments, 7th and 8th African Light Cavalry Regiments, the Colonial Artillery Levant Regiment, the Marine Artillery Group, and three Moroccan Tabor Groups.

Juin directed the French advance beyond Rome. Ordered by Clark to move east of the city and pursue the Germans, Juin formed a corps of the 1st French Motorized Infantry Division and the 3rd Algerian Division, which darted around Lake Bolsena. Within four days it covered 25 miles north of the lake. The French took Sienna on the July 3, 1944. Juin’s forces stabilized the front 10 miles short of the Arno River. North of Rome the FEC fought for 43 consecutive days, inflicted heavy casualties on the enemy, and took 2,080 prisoners.

At the end of July, the FEC was pulled out of the Italian front lines. Clark noted in his diary that Juin had “performed magnificently.” The FEC fought in the Rhone campaign in southern France, but Juin was reassigned to the French high command.

In August 1944, de Gaulle selected Juin as General Chief of Staff of National Defense, a position that Juin held until May 1947. De Gaulle called Juin in that capacity “one of the surest military advisors any French leader ever had.”

Juin was in charge of the expansion of the French Army, tasked with the execution of any of de Gaulle’s decisions, and was de Gaulle’s personal contact with Eisenhower at SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) and General Bernard de Lattre de Tassigny, commander of the French First Army. As chief of staff, Juin represented France at the San Francisco Conference where the United Nations Charter was signed. After the war, he directed the slow rebuilding and modernization of his country’s army.

In August 1944, Juin became embroiled in the decision of whether Allied forces should liberate Paris from German occupation. When Eisenhower initially decided to bypass the city, Juin came face to face with Eisenhower and threatened to order General Philippe Leclerc’s 2nd Armored Division to Paris over Ike’s authority. Juin beseeched Eisenhower to negotiate with the German commander in Paris as well. Eisenhower subsequently ordered the French 2nd Armored and American 4th Infantry Divisions to liberate Paris.

When de Gaulle walked down the Champs-Elysees in triumph, Juin accompanied him. Juin organized the Paris French Forces of the Interior (FFI) into the 10th Division, which moved into combat by September. Juin accompanied de Gaulle during a nine-day conference with Soviet Premier Josef Stalin in early December 1944.

In March 1946, General Juin traveled to the Far East to negotiate with the Nationalist Chinese regarding the withdrawal of Chinese troops from northern Indochina in the Tonkin region of Hanoi-Haiphong. Juin achieved his task and returned to France to continue his responsibilities with the postwar French Army.

In 1947, he returned to Africa as the Resident General of France in Rabat, Morocco, holding the post until 1951, even though he remained in the post of chief of staff of the French Army. He continued to oppose Moroccan attempts to gain independence. In 1947, a nationalist movement threatened French rule. “Morocco,” Juin said, “has a right to be independent. But independence must wait until Morocco is ready.” He applied a policy of military firmness to assure French control.

As chief of staff Juin faced the quagmire of Indochina and the resulting conflict of national policies and concerns. He tried to balance the manpower commitment to the French Expeditionary Force in Indochina and the manpower commitment of the French Occupation Army in Germany and later the French Army’s integration into the NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) command in 1949.

Juin, like Leclerc earlier, eventually became one of the few generals questioning the drain on manpower and other resources associated with the continuing colonial war in Indochina. Asked by the French government to personally inspect the Expeditionary Corps in Indochina, Juin conducted a two-month inspection tour to assess the situation there. By November 1950, he summed it up succinctly: “Is France ready to pay the cost in human lives and money, while compromising our security in Europe to maintain Indochina in the French Union? If the nation does not think so, there are two solutions: first, negotiate with Ho Chi Minh, or second, bring the issue before the United Nations.”

The French government ignored the sage advice and fought four more years, ending its involvement in Indochina in tragic defeat after the debacle at Dien Bien Phu in 1954. Juin’s oldest son, Pierre, fought as a Foreign Legion officer of the 3rd Infantry Regiment in Indochina and survived the war.

With the creation of NATO, Eisenhower, the organization’s supreme commander, tabbed Juin as the Commander-in-Chief Land Forces Central Europe for NATO. On Bastille Day, July 14, 1952, Alphonse Pierre Juin, still holding his NATO post, was promoted to the exalted rank of Marshal of France. In November, he was elected to the elite literary Académie Française. Next came another senior NATO position as he assumed command of CENTAG (the NATO Central Army Group comprised of four army corps) until 1956. He believed that NATO’s forces, when motorized and brought up to planned strength, could quickly seize the initiative in case of an attack by Soviet and Warsaw Pact forces and punch their way eastward.

Following his NATO command, Juin fiercely opposed de Gaulle’s decision to grant independence to Algeria, and he retired in 1962 as a result of the political discord that ensued. De Gaulle may have demanded Juin’s resignation but publicly announced that he was placing Juin “in the reserve of the Republic.” Juin then wrote his memoirs of the Expeditionary Corps in his book La Campagne d’Italie, published in 1962.

Juin was recognized by both American and British military leaders as the top French strategist to emerge from World War II. This was confirmed in a March 11, 1951, Associated Press article when he was selected by Eisenhower as NATO’s ground forces commander. Ike said to reporters, “Juin rivals General de Lattre de Tassigny as one of France’s best military minds.”

Juin was his nation’s last living Marshal of France until his death in Paris in 1967. He was entombed along with other great French military and political leaders, including Napoleon, at Les Invalides in the capital city.

James Marino, military writer, history teacher, and World War II reenactor lives in Hackettstown, New Jersey, and has written extensively on World War II since 1999.

I am curious to learn the composition of French troops in North Africa in 1943? From the sound of the divisions you list above one would guess that the majority were Colonial troops such as muslims and black soldiers. If so why were the French unable to draft white French troops from the hundreds of thousands of white born French living in the Magreb and other French African colonies ?

It would imply a certain reluctance of white French to be involved in the liberation of Europe and their homeland