By John Mancini

Sabotage! Espionage! Mutiny!” Kurt Jahnke, German Chief of Naval Intelligence for North America, read the dispatch from Berlin in his Mexico City headquarters directing him to launch secret missions into Arizona.

The year was 1917. Europe had been awash in blood since August 1914. Russia had just withdrawn from the war, allowing the German Army to shift large concentrations of troops to the Western Front for a massive offensive to be unleashed in the spring of 1918.

But a decisive victory was being threatened by the arrival in France of large numbers of American forces preparing to join the Allied fight. Jahnke’s mission was to create a diversionary threat for the United States along the Mexican border, so that troops targeted for Europe would be retained in America to protect their own soil. Accordingly, Jahnke plotted a number of secret operations in Arizona to ignite a campaign of terror that he felt would force American reevaluation of military priorities.

The plans for terrorizing Arizona included inciting African-American horsemen (nicknamed Buffalo Soldiers by the Indians because their hair resembled the thick coats of buffaloes) of the 9th and 10th Cavalry regiments at Fort Huachuca into a mutiny. Jahnke also wanted to goad the radical labor organization, Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), to launch violent strikes among the Arizona copper-mining companies (copper being especially important to the munitions and communications industries). In concert with these uprisings, military formations of German reservists who had fled to Mexico from the United States after the declaration of war in April 1917 would make assaults and raids across the American border. To accomplish these sinister objectives Jahnke selected three men.

For the leader, he chose the bold and daring, 22-year-old naval officer Lothar Witzke. The man had served as a lieutenant on the cruiser Dresden when it was trapped by the British Navy near the coast of Chile in March 1915. Rather than accept capture by the British, the crew destroyed the ship and chose internment in Chile. But the aggressive Witzke was able to ship out as a merchant seaman on an American vessel bound for San Francisco. (Coincidentally, the future head of Military Intelligence for the Third Reich was Wilhelm Canaris, also a young German officer on the Dresden, who also disguised himself to escape Chile.)

When Witzke disembarked in San Francisco he got in touch with the German Consul General Franz Von Bopp, quickly volunteering for espionage and sabotage missions in the United States. After a short period of duty as a courier, saboteur, and agent in San Francisco, Witzke was transferred to New York, where German agents were actively and successfully pursuing a reign of sabotage against American shipping.

Jahnke also picked Dr. Paul Altendorf. Jewish, born in Poland, Altendorf had studied medicine at the University of Cracow and was a chiropodist. At some time in his shadowy background he moved to Austria, from which he then fled in the 1890s to evade service in the army.

For almost 20 years Altendorf traveled throughout Europe, the Middle East, and South America, eventually finding his way to Mexico. By then he was fluent in German, Spanish, and English. German agents recruited him into their espionage network in Mexico. They also helped him gain the rank of colonel in the Mexican Army and an assignment to the military government of the state of Sonora, which bordered Arizona.

The third member of the team was William Gleaves. He was a black Canadian, born in Montreal in 1870. He had lived for a time in Pennsylvania before moving to Mexico in 1893. The Germans recruited him in 1915. For Jahnke’s purposes, Gleaves was the man both to join the IWW in hopes of igniting strikes among copper miners and to encourage African-American soldiers at the border posts to mutiny.

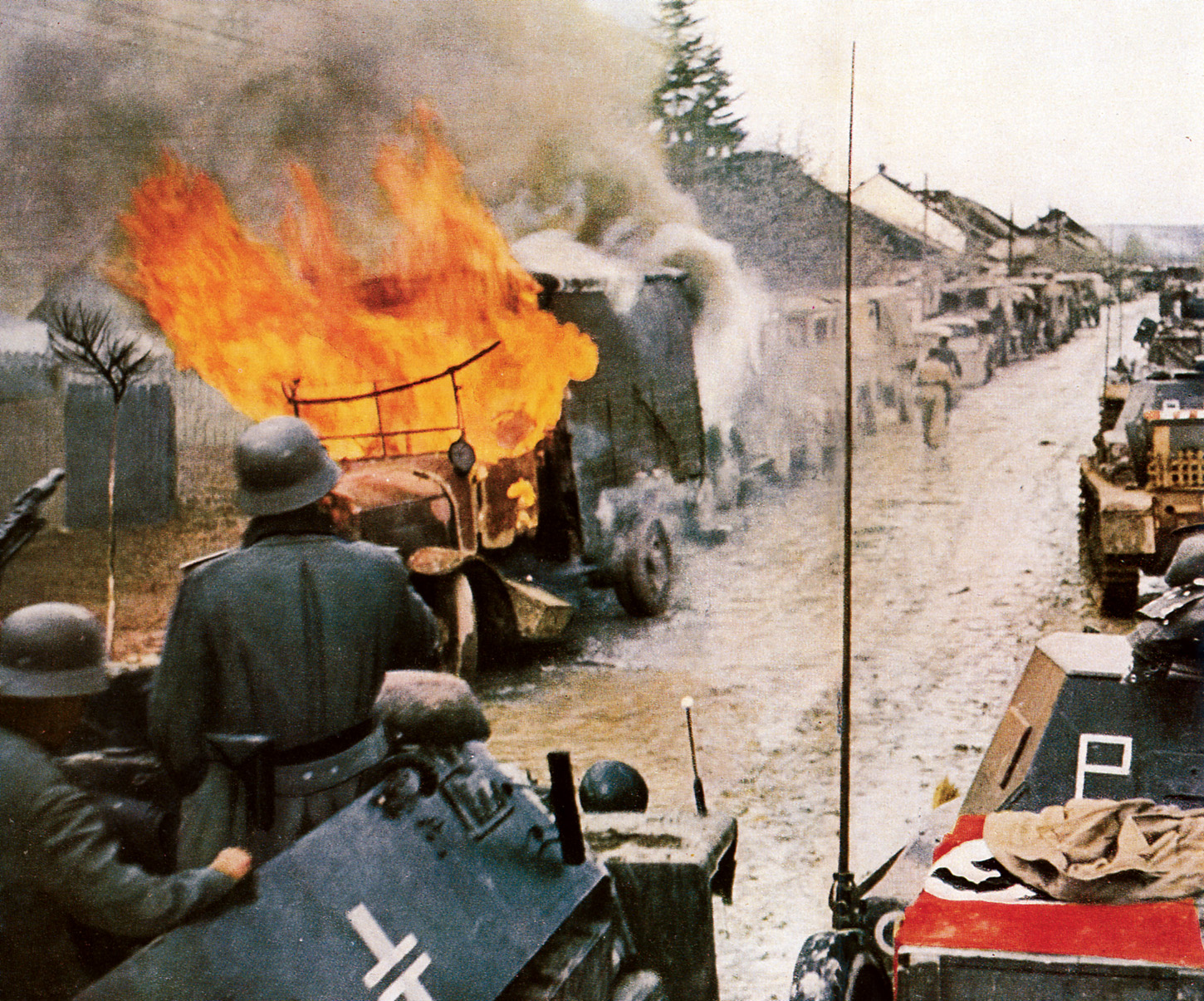

Mexico was fertile ground in those days for international intrigue and exploitation. Unrest that had been festering for decades burst into violent revolution in 1910. Adding to Mexico’s political turmoil was the emergence of marauding guerrilla armies led by Pancho Villa, Zapata, and Obregon. These forces were essentially private armies whose primary loyalties were to themselves and their chief.

As the flames of violence burned across Mexico, ranches, settlements, and towns along the border lived in fear of attack by Mexican revolutionaries. The dreaded nightmare finally materialized. At about 4 am on March 9, 1916, Villa, with four to five hundred riders, attacked the sleeping town of Columbus, NM. Soon regimental guidons snapped in the wind as U.S. Army units from throughout the Southwest rode to join General Pershing for a retaliatory strike into Mexico. Twelve thousand American troops stormed across the Mexican border.

The German government hoped for a long campaign. The prospect of the United States becoming involved in a drawn-out war in the deserts and mountains of Mexico was exactly what the German strategists wanted.

Germany was not the only one eyeing these troubles from overseas; so was Japan. Indeed, as an emerging naval power in the Pacific, no one could dismiss the thought that Japan would keenly watch the eastern edge of that ocean, particularly Mexico, Latin America, and the Panama Canal. Anxiety over Japan’s interest fueled concern among Americans about their southern border. Rumors abounded of a Mexican plot to regain the land lost in the 1848 war with the help of Germany and Japan. Fear of Japanese expansion on U.S. borders, in fact, had existed for years.

In 1908, there was rumor of a secret treaty between Japan and Mexico, and reports of Japanese officers serving with the armies of Huerta, Carranza, and Villa. Fear grew of a Japanese invasion of the United States through Mexico, using the Mexican railway system to transport troops to the American border from landings at Pacific and Gulf of California ports.

In April 1915 the Japanese cruiser Asama, in a rather mysterious and curious accident, ran aground while on patrol in the Gulf of California. Other Japanese warships were also reported in these waters. Indian scouts reported to U.S. Army commanders posted along the Arizona border that bands of “Chinos,” that is, Japanese, regularly moved through northern Mexico.

Captain Sidney Mashbir of the Arizona National Guard was dispatched on a secret mission by General Frederick Funston to verify the reports of Japanese operating in northern Sonora. Mashbir led a small patrol into the rugged desert of southern Arizona and northern Sonora. He followed a route he assumed the Japanese infantry would have taken from the Gulf of California. His blood chilled under the hot desert sun one day as his eyes scanned ideographs written in charcoal on the rock walls of several canyons. They were apparently messages left by Japanese patrols. Mashbir methodically and laboriously drew copies of the symbols and sent them to Washington, DC, for analysis. The response to the mysterious messages was disappointing and frustrating. It read, “The writings have no military significance.”

But Mashbir remained convinced that he and his patrol had verified that several companies of Japanese infantry from the Asama had marched inland, conducted secret operations in northern Mexico, and crossed into southern Arizona.

Whether the Japanese had been there or not in 1915, the Germans were operating more or less at will south of the border. The Carranza government expressed neutrality, but it was strongly pro-German, and the Kaiser’s agents roamed freely. On January 16, 1918 Witzke, using the alias of Pablo Waberski, left Mexico City along with Altendorf and Gleaves. The three men traveled to the port of Manzanilla where they boarded a ship bound for Mazatlan. From there they took a train over the rugged northern Sonora desert to the Arizona border town of Nogales.

During the long and dangerous journey through bandit- and revolutionary-plagued Mexico, Witzke drank heavily to pass the time. It was a risky action for any secret agent. For the more he drank, the more he talked.

“I’m going to blow things up in the United States,” he once blurted. “There is something terrible going to happen on the other side of the border when I get there.”

The bleary-eyed Witzke boasted of blowing up munitions depots at Mare Island near San Francisco and Black Tom Island near New York City. “I have many lives on my conscience and I have killed many people, and will now kill more,” he grimly added.

In fact, Witzke did blow up a munitions depot at Black Tom Island, NJ, on July 30, 1916. He and Kurt Jahnke and a third accomplice rowed silently across the Hudson River to the large ammunition dump at Black Tom Island, a major terminal for the shipment of munitions to France and England. Despite U.S. neutrality, it was the major supplier of war materiel to Germany’s enemies. At 2:08 am the three men set off explosions that blew the ammo dump up, alighting the skies over New York City and New Jersey.

But that was more than a year past, and the United States had more experience with counterintelligence than it did then. While Witzke, Altendorf, and Gleaves were riding the train north toward Arizona, a smile tugged at the lips of Special Agent Byron S. Butcher of the Corps of Intelligence Police stationed at Nogales, AZ. He was holding a telegram sent from the American Counsel in Mazatlan. It contained information from a secret operative in Mexico, code named A-1, saying that German agents were planning to cross the border at Nogales.

Under the leadership of Ralph H. Van Deman, a man who had delved into spying during the Philippine insurrection, Army Intelligence had been struggling to establish itself in the shadowy world of international espionage. The Black Tom explosion on July 30, 1916, and an even more unsettling disclosure in early 1917—the infamous Zimmerman Telegram—had confronted America with the chilling need for spies and counterspies.

Early in 1917, British Intelligence intercepted and decoded a telegram from the German foreign secretary Arthur Zimmermann to the German Ambassador in Mexico. “We intend to begin unrestricted submarine warfare on the first of February,” Zimmerman wrote. “We shall endeavor in spite of this to keep the United States neutral. In the event of this not succeeding, we will make Mexico a proposal of alliance on the following basis: Make war together, make peace together, generous financial support, and an understanding on our part that Mexico is to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico and Arizona.”

The British showed it to the Americans. President Wilson released it to the public in March 1917, and anger over its contents did much to bring about the eventual declaration of war against Germany on April 6.

So the Americans were paying what special attention they could to Mexican affairs and the long border they shared with that country. On the morning of February 1, 1918 Witzke crossed from Mexico to the United States using a Russian passport under the name of Pablo Waberski. As he walked confidently down a Nogales street toward the bank, Special Agent Butcher and another agent swiftly moved in. The stunned Witzke felt the barrels of two revolvers in his back, followed by the snap of handcuffs around his wrists and a forceful shove into a waiting car for a drive to a nearby army camp.

A search of Witzke revealed $175 in gold and $750 in currency. But there were no documents or incriminating evidence that would identify him as a German agent. Interrogation efforts were equally unsuccessful.

So Butcher crossed the border into Nogales, Mexico, and returned with baggage that Witzke had left in a hotel room. A search of his belongings produced a mysterious coded letter and code cipher. These were sent to the Military Intelligence code-breaking center in Washington, DC. After an exhaustive, 72-hour, non-stop, intellectual endurance effort, the complex code was broken.

The message, dated January 15, 1918, was written by Heinrich von Eckhardt, the German Minister in Mexico City. Clearly it was an introduction to German diplomatic authorities and read as follows:

“To the Imperial Counselor Authorities in the Republic of Mexico. Strictly Secret. The bearer of this is a subject of the Empire who travels as a Russian under the name of Pablo Waberski. He is a secret agent. Please furnish him protection and assistance on request and advance him on demand up to one thousand pesos in Mexican gold, and send his code telegrams to this Embassy as official dispatches.”

Despite this evidence, Witzke maintained he was innocent of the charge of being a spy. He held to his cover story of simply being a messenger and maintained that he was “set up” by mysterious Mexican and German individuals. But, the testimony of two key witnesses cinched the case for the U.S. government.

The operative known to Special Agent Butcher as A-1 was able to provide firsthand accounts of Witzke’s statements and actions. He was Dr. Paul Altendorf. And Altendorf’s testimony was corroborated by another firsthand observer, William Gleaves, who was an agent for British Intelligence. Both men had penetrated the German mission and operated in total ignorance of each other’s counterintelligence identity.

Witzke was found guilty by a military court in August at Fort Sam Houston, TX, and sentenced to hang. He became the only enemy agent in the United States to be given a death sentence during the Great War.

In May 1920, President Wilson commuted his sentence to life in prison. But in 1923, in response to German diplomatic pressure, Witzke was returned to Germany, where he was awarded the Iron Cross. One reason for Witzke’s release was his heroic actions in rescuing fellow prisoners during a boiler room explosion at the Fort Leavenworth Military Prison.

Lucky to be alive, Lothar Witzke nevertheless returned to the shadowy world of international intrigue. Presumably working for German Intelligence, he appeared in Venezuela in 1927. In 1932 he joined the Nazi Party. In 1933 he surfaced in China. He was last seen in 1936.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments