By Carole E. Scott

The Confederate States of America fought two wars, one against the armed forces of the United States and one against fellow Southerners who joined either the Union Army or pro-Union guerrilla groups. Although they came from all classes, most Southern Unionists differed socially, culturally, and economically from their region’s dominant prewar, slave-owning planter class. As many as 100,000 men living in the 11 Confederate states eventually served in the Union Army. The majority of them were from Tennessee, North Carolina, and Virginia/West Virginia.

Opposition to Secession and Slave-Owners

In 1860, most white residents of the slave states did not live in the so-called “plantation belt.” Instead, they lived in areas substantially populated by small farmers and herdsmen who owned few if any slaves. Opposition to secession was greatest in slave states sharing a border with a free state. Border state slave owners may have feared that many of their slaves would successfully run away if their state left the Union because the Fugitive Slave Act, which required that runaways who reached free states be returned to their owners, might be repealed.

The 13 states the Confederate government claimed included Missouri and Kentucky, which did not formally secede from the Union. Maryland was not included. To keep Washington, D.C., from being surrounded by the Confederacy, the Federal government quickly imposed martial law in Maryland and garrisoned it with Union troops, thus effectively preventing the state from leaving the Union.

Most of the white Southerners who chose to join the Union Army lived in the Confederacy’s border states and the Deep South’s relatively poor “white counties,” which were too infertile to support plantation agriculture. As a result, they had few if any black residents, either slaves or freedmen. White counties were concentrated in but not confined to the Appalachian Mountains—western Virginia, eastern Kentucky, western North Carolina, eastern Tennessee, northern Georgia, and northern Alabama. Many Southern Unionists in these states shared Northerners’ hatred of the region’s aristocratic, slave-owning oligarchy.

Widespread opposition to secession initially kept Virginia in the Union. Such opposition was strongest in western Virginia, where only one out of 100 voters owned slaves. Nonetheless, half of Virginia’s northwestern counties (which in 1863 became the state of West Virginia) were in favor of Virginia seceding. As many as half of West Virginia’s eligible men later fought for the Confederacy.

So strong was pro-Union sentiment in mountainous North Alabama and adjoining East Tennessee that it was proposed the two regions unite to form a new loyal state called Nickajack. Representatives from 26 counties in East Tennessee’s mountainous, grain-growing and stock-raising region agreed to secede from Tennessee. Their petition to do so was rejected by the state legislature, and Confederate troops were sent to occupy East Tennessee to prevent its secession. In East Tennessee the vast majority of whites owned no slaves, and Union supporters outnumbered Confederate supporters. The majority of Confederate soldiers did not own slaves.

Punitive Tactics against Confederate Bushwhackers

When the war began, Union leaders greatly overestimated how many Southern civilians were Unionists at heart and assumed that if they were treated well they would turn against the Confederacy. When that proved not to be the case, President Abraham Lincoln and his generals turned to a hard war policy that targeted anything and everything that might help the Confederacy. To deal with Confederate guerrillas, executions and the destruction and confiscation of property were allowed. In Kentucky, Union Maj. Gen. Stephen G. Burbridge executed four Confederate prisoners for every Union soldier or citizen killed by bushwhackers—a name originally used only to describe Confederate guerrillas.

When Union Colonel William Weer of the Army of the Frontier was in Carrollton, Arkansas, he issued a draconian order on April 4, 1863: “It having come to the knowledge of the colonel commanding that the forage trains of this command are repeatedly fired into on Osage Fork of Kings River by lawless men, who secrete themselves in the bushes and are encouraged and entertained by the inhabitants in that vicinity, you are therefore instructed to proceed to said neighborhood with the wagons placed in your charge, destroy every house and farm etc. owned by secessionists, together with their property that cannot be made available to the army; kill every bushwhacker you find; bring away the women and children to this place, with provision enough to support them, and report to these headquarters upon your return.”

Pro-Union Guerrillas of the South

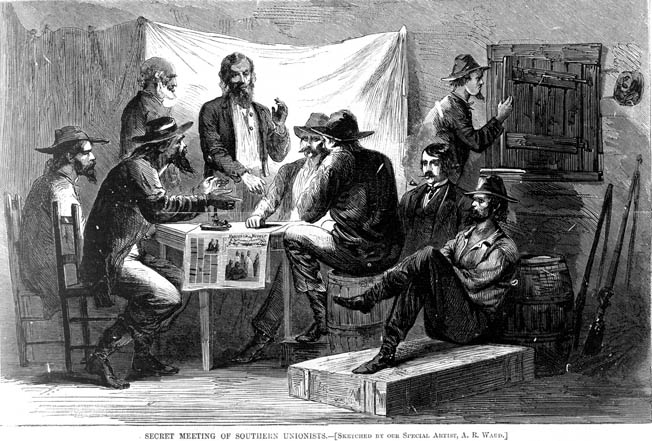

Pro-Union Southerners who organized guerrilla bands had a variety of objectives. Among them were controlling their community politically and economically; harassing and defending themselves from representatives of the Confederacy; assisting the Union Army; and resisting attacks from neighbors who supported the Confederacy. Vicious, neighbor-against-neighbor guerrilla activity was worst in Arkansas, Kentucky, Missouri, Tennessee, and Virginia/West Virginia.

In Tennessee and the adjacent areas of Kentucky, the Cumberland Mountains provided ideal conditions for guerrilla warfare. The section’s isolated territory, much of it rough and inaccessible, made it suitable terrain for irregular warfare. Moreover, residents there clung to traditions that encouraged the growth of guerrilla bands— retribution, family feuds, class conflicts, vigilantism, and backwoods opposition to authority. Some Unionist guerrilla bands were composed of draftees who had deserted from the Confederate Army, men trying to avoid being conscripted into the army, and genuine outlaws whose objective was simply to prey on others. Roaming bands took advantage of the war to steal and rob. Acts of murder, arson, torture, intimidation, robbery, and pillage were so prevalent in some places that those loyal to the Confederacy simply fled to more congenial surroundings.

Throughout the war, both the Union and Confederate armies were negatively affected by guerrilla groups. A full-scale guerrilla war that began before 1861 continued to fester in Missouri. West Virginia authorized guerrilla groups organized to fight Confederate guerrilla groups to operate as state troops. But regular Union troops and Unionist guerrillas were only able to prevent loyal West Virginians from having to flee their homes and guard against any major damage to the vital Baltimore & Ohio Railroad.

“The Night of the Burning Bridges”

In August 1861, the Confederate Congress passed an Alien Enemies Act that gave people 40 days to swear allegiance to the Confederacy or else leave the South. Failure to do so subjected one to arrest and expulsion. A Sequestration Act called for the property of disloyal Southerners to be confiscated and sold at a public auction. Many East Tennesseans lost their homes and property as a result of the act, leading to the most serious and determined act of pro-Union sabotage of the war. It would become known as “the Night of the Burning Bridges.”

Unionist East Tennessee was important to the Union war effort because the railroads that ran through it were linked to the rest of the Confederacy. In 1861, William Blount Carter, a Unionist Presbyterian minister in Tennessee whose brother was a Union general, proposed to Union Brig. Gen. George H. Thomas that Unionists burn down nine bridges in East Tennessee to destroy the rail and telegraph connections between Virginia and Georgia. The plan called for Unionists to set fire to the bridges on the night of November 8. The burning of the bridges would be followed by an uprising of armed Unionists against the Confederacy and Thomas’s troops invading and liberating East Tennessee from their camps in Kentucky.

After meeting with Thomas, Carter traveled to Washington to outline his scheme for President Lincoln, Secretary of State William Henry Seward, and Maj. Gen. George McClellan, the army commander. Lincoln approved the venture, and Carter left the capital with $2,500 for expenses and a firm commitment from Lincoln for a Federal invasion of East Tennessee. Accompanied by Union Captains William Cross and David Fry, Carter quickly recruited 11 other cohorts for the raid. He selected local Unionist A.M. Cate to lead an attack on four bridges in southeast Tennessee and Robert W. Ragan and James D. Keener to strike the strategically vital bridge across the Tennessee River at Bridgeport, Alabama. Other groups would hit bridges between Chattanooga and Knoxville.

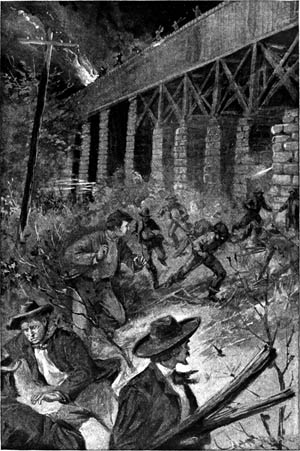

On the appointed night, the bridge burners set out. Ragan and Kenner were unable to burn the Bridgeport span, which was swarming with Confederate defenders, but Cate and his men managed to burn four bridges across the Hiwassee River around Charleston and Cleveland, Tennessee. In Marion County, 30 miles north of Bridgeport, Cate’s brother, W.T. Cate, managed with his henchmen to set fire to bridges east of Chattanooga on the Western & Atlantic and East Tennessee & Georgia Railroads.

Fifteen miles northeast of Knoxville, another Unionist, William C. Pickens, led a group of a dozen sympathizers in an assault on an East Tennessee & Virginia Railroad bridge crossing the Holston River at Strawberry Plains. Carrying a lighted torch, Pickens crept along the riverbank. He was just about to fire the bridge when a bullet smashed into his thigh. James Keelan, the lone watchman, grabbed Pickens and held on for dear life while other Unionists stabbed wildly at the pair, accidentally wounding Pickens in the process. Keelan, wounded by gunfire, staggered off to summon help while the frustrated Pickens, who had dropped the group’s only set of matches during the struggle, limped away under cover of darkness.

In upper East Tennessee, Captain David Fry and Daniel Stover (Senator Andrew Johnson’s son-in-law) led separate assaults on bridges in Greene and Sullivan Counties. While the bridges burned, separate groups of Unionists skirmished with Confederate forces at Strawberry Plains, Union Depot, and Carter Depot. As late as two weeks later, Confederate regulars were flushing out loyalists in mountain coves along the Doe River.

Reacting to the East Tennessee Uprising

News of the night’s destruction swept quickly across the South. Colonel W.B. Wood, the Confederate commander at Knoxville, informed General Samuel Cooper on November 11, “My fears expressed to you by letters and dispatches of 4th and 5th instant have been realized by the destruction of no less than five railroad bridges—two on the East Tennessee and Virginia road, one on the East Tennessee and Georgia road and two on the Western and Atlantic road. The indications were apparent to me but I was powerless to avert it. The whole country is now in a state of rebellion. A thousand men are within six miles of Strawberry Plains bridge and an attack is contemplated to-morrow. I have sent Col. Powel there with 200 infantry, one company cavalry and about 100 citizens armed with shotguns and country rifles. Five hundred Unionists left Hamilton County today we suppose to attack Loudon bridge. I have Major Campbell there with 200 infantry and one company cavalry. I have about the same force at this point and a cavalry company at Watauga bridge. The slow course of civil law in punishing such incendiaries it seems to me will not have the salutary effect which is desirable. I learn from two gentlemen just arrived that another camp is being formed about ten miles from here in Sevier County and already 300 are in camp. They are being reinforced from Blount, Roane, Johnson, Greene, Carter and other counties. I need not say that great alarm is felt by the few Southern men. They are finding places of safety for their families and would gladly enlist if we had arms to furnish them.”

Panic swept across East Tennessee while Confederate officials rushed reinforcements into the area from Richmond, Memphis, and Mobile. The Confederate commander in the district, Brig. Gen. Felix Zollicoffer, who had worked hard to protect Unionists’ personal and property rights, felt betrayed by the night’s events. “The leniency shown them has been unavailing,” he said. “They have acted with base duplicity and should no longer be trusted.” He instructed Wood to disarm all suspected Union sympathizers and throw them in jail.

In a November 20 telegram, Wood assured Confederate Secretary of War Judah Benjamin, “The rebellion in East Tennessee has been put down in some of the counties, and will be effectually suppressed in less than two weeks in all the counties. We have now in custody some of their leaders, Judge Patterson, the son-in-law of Andrew Johnson, Col. Pickens, the senator from Sevier, and others of influence and some distinction in their counties. They really deserve the gallows, and, if consistent with the laws, ought speedily to receive their deserts.”

Benjamin responded, “Your report of the 20th instant is received, and I now proceed to give you the desired instruction in relation to the prisoners of war taken by you among the traitors of East Tennessee. First. All such as can be identified in having been engaged in bridge-burning are to be tried summarily by drum-head court martial, and, if found guilty, executed on the spot by hanging in the vicinity of the burned bridges. Second. All such as have not been so engaged are to be treated as prisoners of war, and sent with an armed guard to Tuscaloosa, Alabama, there to be kept imprisoned at the depot selected by the Government for prisoners of war…. In no case is one of the men known to have been up in arms against the Government to be released on any pledge or oath of allegiance. The time for such measures is past. They are all to be held as prisoners of war and held in jail till the end of the war.”

As many as 1,000 prominent and not so prominent East Tennesseans were arrested and taken to Knoxville. Five men were hanged, and 400 were imprisoned in Alabama. The number of Confederate soldiers in Knoxville quadrupled, with roughly one soldier for every man, woman, and child in the city. Wood sent squads of men door to door to confiscate firearms from the entire civilian population.

Ultimately, East Tennessee Unionists were left holding the bag because Thomas, who had been on his way to support them, was recalled at the last moment by his superior, Brig. Gen. William T. Sherman, and ordered to hold Cumberland Gap against a suspected attack. Thomas protested, but it was too late to warn the bridge burners of the change of plans. In the end, the attack Sherman feared never came.

In explaining why people in East Tennessee remained loyal to the Union, Samuel W. Scott, a captain in the 13th Regiment Tennessee (Union) Volunteer Cavalry and Samuel P. Angel, the regiment’s adjutant, later wrote, “One reason may be found in the fact that the soil and climate are not adapted to the growth of cotton, rice and tobacco, the great staples of the South, hence slave labor could not be employed to the same advantage as in the Cotton States. The people, or a large number of them, were comparatively poor and earned their living by daily labor. They were not slow to perceive that slave labor must enter into competition with them, lessen their wages and their chances of employment, and diminish their opportunity to better their condition either socially or financially. They could see that by fighting for slavery they were only fastening upon themselves the yoke of poverty, and the ban of social ostracism, hence slavery was not a question of paramount importance to them, unless it was its abolition.”

James Gallant Spears: Slave Owner on the Union Side

James Gallant Spears, who fled from his native Tennessee to Kentucky, where he organized the 1st Tennessee (Union) Infantry, was one of the relatively few slave owners who sided with the Union and fought for it. Promoted to brigadier general in the Union Army, Spears served until February 6, 1864, when he was arrested because of his expression in violent language of his belief that the Emancipation Proclamation was illegal and unconstitutional. Refusing to resign, he was dismissed from the service the following August.

Spears did not realize when he decided to fight for the Union that its victory would cost him his slaves. That was not an unreasonable assumption. In his first inaugural address, Lincoln had pledged “that the maintenance inviolate of the rights of the States, and especially the right of each State to order and control its own domestic institutions according to its own judgment exclusively, is essential to that balance of power on which the perfection and endurance of our political fabric depend; and we denounce the lawless invasion by armed force of the soil of any State or Territory, no matter what pretext, as among the gravest of crimes.”

Spears might also have been influenced by Congress’s passage of the Corwin Amendment shortly before Lincoln’s inauguration in 1861, which stated, “No amendment shall be made to the Constitution which will authorize or give to Congress the power to abolish or interfere, within any State, with the domestic institutions thereof, including that of persons held to labor or service by the laws of said State.” Lincoln was willing to accept the amendment, but only two states ratified it before it became a dead letter.

William G. “Parson” Bownlow of East Tennessee

To explain why Tennessee had seceded, the 13th Tennessee’s Scott and Angel wrote, “The proclamation of Mr. Lincoln calling out troops and his well-known anti-slavery sentiments were used by the advocates of secession to alarm the slave-holders of the State, and many of those who were loyal to the Government were driven into secession by this false alarm. No sane man now believes that Mr. Lincoln would have freed the slaves had not the Southern people gone into rebellion. He did it, at last, with much hesitation, believing it the only means of preserving the Union.”

East Tennessee’s William G. “Parson” Bownlow, a fiery and controversial minister, opponent of secession, and editor of an influential Whig newspaper, said there were three essential traits of a true Unionist: an “uncompromising devotion” to the Union, an “unmitigated hostility” to the Confederacy, and a willingness to risk life and property “in defense of the Glorious Stars and Stripes.” Brownlow, who called secessionists “imps from Hell,” said that Unionists who had suffered at their hands were “justified in shooting them down on sight.” Some followed his advice.

One of the more significant of Tennessee’s Union Army units was the 1st Regiment of Tennessee Volunteer Cavalry. On its battle flag were emblazoned Chickamauga, Chattanooga, Knoxville, Atlanta, Nashville, and Franklin. Organized out of state, its first commander was a son of Lincoln’s second vice president and the only senator from a Confederate state to remain in the Senate, Andrew Johnson. Later, Brownlow’s son led the 1st Tennessee.

Armed bands roamed over the countryside, pilfering, robbing, and murdering peaceful citizens, and martial law was declared in East Tennessee. Provost marshals and enrolling offices were appointed in every town and county, and these were composed usually of the bitterest and most oppressive men in the Confederacy. Enlisting in the Union Army was difficult because the nearest Union camps were in Kentucky, and the routes to the Bluegrass State were well guarded. Capture meant sudden death or long confinement in some loathsome prison. Most who made the trip successfully did so at night. During the war, Carter said, Colonel Brownlow and his regiment participated in more than 50 battles and skirmishes. Brownlow had four horses shot from under him and was severely wounded at the Battle of Franklin in November 1864.

Deserting the Confederacy

Like Tennessee, pro-Union sentiment in North Carolina was concentrated in but not confined to the mountains on its western side. An estimated four to six percent of white males in North Carolina were Unionists, and 35 of its 90 counties experienced some kind of guerrilla activity. In coastal North Carolina, the 1st and 2nd North Carolina (Union) Volunteer Infantry were organized. In western North Carolina the 2nd and 3rd North Carolina (Union) Mounted Infantry were organized. A New York Tribune correspondent reported that the men in North Carolina’s 1st and 2nd Union Regiments had “a bitter and malignant feeling toward their disloyal neighbors and hated slavery and slaveholders whom they believed responsible [for their impoverished] condition.”

The eastern regiments were promised they would not have to leave North Carolina and that their families would be protected by troops from the North, which usually accompanied them on their operations. The 2nd North Carolina enlisted Confederate deserters and poor men attracted by a $300 bounty. The western regiments, which were told to take no prisoners and shoot guerrillas on sight, were much feared by Confederate civilians.

In central North Carolina there were long-established antislavery Quaker and Moravian communities. Anti-Confederate activities by members of these communities included helping escaped Union POWs and runaway slaves and convincing Confederate soldiers to desert. Deserters from the Confederate Army and men hiding out in Quaker Belt counties to avoid being conscripted responded to bullying and physical abuse by turning to guerrilla warfare. (Some Quakers and Moravians owned slaves and fought for the Confederacy.) In Virginia, Confederate General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson sent troops to round up Mennonites who refused to serve in the Confederate Army. Concerned that they might aim rifles badly, he assigned them to noncombat duties.

By war’s end, an estimated 100,000 men had deserted from the Confederate Army. Desertion was most prevalent among poor men and those fighting near their homes. Mountainous North Georgia, which accounted for the majority of Georgia’s Confederate deserters, provided only 14 percent of its Confederate units. More than 50 percent of Georgia’s Confederate volunteer infantry companies hailed from its plantation belt counties. Their desertion rates were among the lowest in the state.

Deserters in both the Union and Confederate armies might face firing squads. The Federal government encouraged men to desert from the Confederate Army by pardoning and restoring their citizenship rights and allowing them to go home if they took a loyalty oath to the Union. In August 1864, Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses Grant rewarded Confederate deserters with monetary incentives and transport home. By that time many Confederate soldiers were underfed, shoeless, lice infested, and clad in rags.

Bands of deserters hid out in the South Carolina hill country. A force of more than 500 deserters controlled an area at the border with North Carolina; their desertion rate was the highest in the Confederacy. These deserters fought with Confederate forces, stole supplies, robbed supporters of the Confederacy, and burned their property. No white Union Army units were organized in South Carolina.

In North Carolina in 1863, 13 Unionists were executed without trial in Madison County, a Unionist stronghold. Their execution was the result of armed Unionists stealing salt, a valuable commodity in the Confederacy, and looting the homes of secessionists, including that of a colonel in command of a Confederate army regiment. His wife and three small children, two of whom shortly afterward died of scarlet fever, were terrorized. Some of the Unionists were deserters from the colonel’s own regiment.

The colonel and his regiment left Tennessee, where they were guarding another stockpile of salt, to deal with the Unionist band. Hoping this would force the Unionists’ wives and mothers to reveal where they were, these women were brutally tortured. All the Unionists who were executed belonged to the same poor family, the Sheltons. North Carolina’s Confederate governor, Zebulon Vance, who tried to prevent any executions from taking place, labeled the affair “shocking and outrageous in the extreme.” The colonel was suspended for six months, and his second in command was court-martialed and resigned. In a subsequent attempt to retake New Bern, North Carolina, Confederate forces captured 53 members of the 2nd North Carolina (Union) Volunteers, who were identified as deserters from the Confederate Army. Twenty-two of them subsequently were hanged.

The Battle of Nueces

A band of Confederate deserters from Jones and adjacent counties in southern Mississippi fought several skirmishes with Confederate forces and temporarily overthrew Jones’s Confederate government. These men distributed to local residents corn collected by the Confederates as a tax-in-kind. Among the factors motivating the non-slave-owning farmers and herdsmen to desert was taxation and anger over the “Twenty Negro Law,” which exempted owners of 20 or more slaves from service in the Confederate Army. Only 12 percent of Jones’s population consisted of slaves.

Resistance to the slave-owning draft exemption was also widespread in Texas, particularly in those areas of north and central Texas with large German immigrant populations. Many Germans had immigrated to Texas in the 1850s, following the failed Revolution of 1848. These Germans had come to Texas to find personal and religious freedom, and they were adamantly opposed to slavery. After the Civil War started and it became apparent that the struggle would be a long one, many Germans protested against the Confederate government, particularly after the Conscription Act was passed in April 1862.

Confederate authorities responded forcefully, occupying the German town of Fredericksburg on the Pedernales River in Gillespie County. The local Confederate commander, Captain James Duff, threatened to “hang all I suspect of being anti-Confederate” and stepped up his persecution of Germans, whom he called “damn Dutchmen.” Gillespie and several neighboring counties were put under martial law.

In the summer of 1862, German Unionists in Kerr County organized a militia company under Major Fritz Tegener and marched south, intending to avoid the draft by fleeing to Mexico. As soon as Duff learned about the movement, he sent a strong force under Lieutenant C.D. McRae to catch up with them. On August 9, as the refugees camped alongside the Nueces River, McRae’s Confederates surrounded the camp and poured fire into the sleeping men. Nineteen Germans were killed by gunfire, and another six were trampled to death by McRae’s cavalry. Another nine surrendered and were summarily hanged. McRae grimly reported to Duff, “We met determined resistance, hence I have no prisoners to report.”

The Great Hanging at Gainesville

Shortly after the one-sided Battle of Nueces, what may have been the nation’s greatest instance of vigilante violence took place in Gainesville, the county seat of Cooke County, Texas. Less than 10 percent of the county’s heads of household owned slaves. Hostility between the county’s earlier pro-slavery settlers and recent settlers from free states and from Germany predated the Civil War. Outraging slave owners were abolitionist Methodist preachers from Kansas, one of whom was lynched in another North Texas county before the war.

In October 1862, Colonel William C. Young, Cooke County’s wealthiest slave owner, reported that he had received information that “a vile and secret organization” existed in the county to “overthrow the government both State and Confederate, the seizure and destruction of property, both public and private; the perfecting of an alliance with the invading armies, both civilized [Union army] and uncivilized [pro-Union Indians] now gathering upon our borders, and the indiscriminate slaughter of ourselves, our wives and children.” He said a plan for self-defense was necessary.

Young, a veteran of the Mexican War and a former lawman, headed the 11th Texas Cavalry, a unit he had organized and in which his son also served. Of great concern to Young and others who shared his views was the fact that Cooke County residents had voted 221 to 137 against secession. The editor of the Sherman Patriot, a local Whig newspaper, recently had proposed that North Texas secede from Texas and become a new free state. Thirty county residents calling themselves the Peace Party signed a petition protesting the exemption from the draft of Cooke County’s largest slave owners. A strong Union League presence developed in Cooke, Wise, Denton, Grayson, and Collin Counties. Members exchanged secret signs, handshakes, and passwords at frequent meetings to discuss resistance to Confederate authorities.

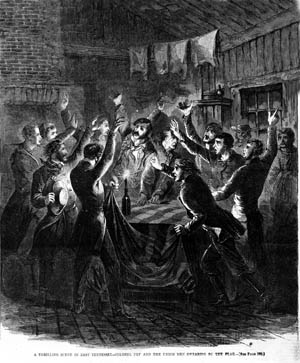

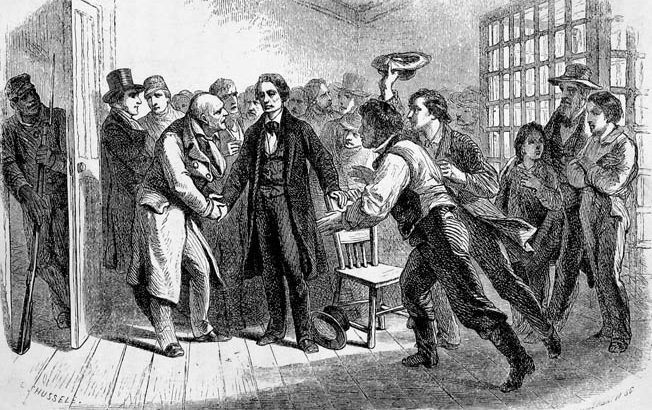

One such meeting, at Rock Creek near Gainesville in early October 1862, led to an unimaginable tragedy. After the young son of a loyal Confederate told his father that Union Leaguers had threatened to kill him after he stumbled on their meeting, Texas state troops arrested 159 men suspected of being members of the group. The prisoners were brought into Gainesville, where a large, unruly mob thronged the streets. One witness recalled, “When I arrived near town, I saw crowds in every direction, armed and pressing forward prisoners under guard. The deepest and most intense excitement that I ever saw prevailed. There were three or four hundred men in sight. All reason had disappeared.” Someone shouted, “Shoot all prisoners where they now stand!”

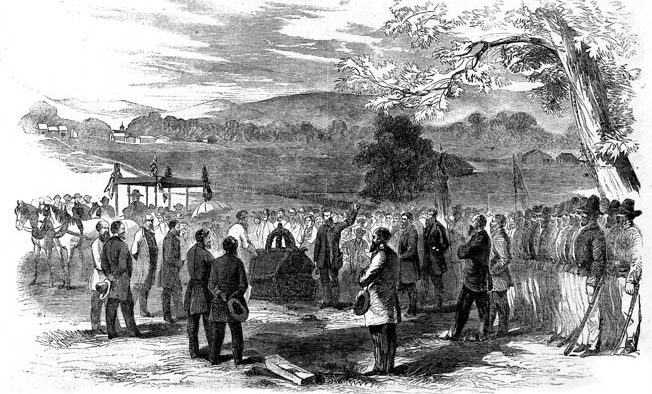

To quiet the mob, local leaders immediately called a special town meeting. A 12-man, extralegal “citizens court” jury that included Young and six other slave owners tried the men for treason and insurrection. Based on a two-thirds majority vote, seven Unionists were convicted and hanged, including Henry Childs and his brother Ephraim. After the court adjourned for a week, an angry mob stormed the jail and demanded that 14 other Unionists be hanged as well. Panicked jailers complied, and the men were taken, three or four at a time, to an elm tree on the banks of Pecan Creek. Their bodies were then thrown into an unoccupied building along with those of two other luckless deserters who had also been hanged by the mob.

In all, at least 41 suspected Unionists were killed in Gainesville during the “hanging days” of October 1862. Other Unionists were hanged in the adjoining counties of Wise and Grayson. The Reverend Thomas Barrett, a Disciples of Christ minister who had served on the initial citizens’ jury in a vain effort to spare the prisoners, said the number was too low. Barrett alleged that many other Unionists who had come into Gainesville to surrender had been hanged without any sort of trial whatsoever, “quick victims of lynch law.” One of those hanged was the editor of the Sherman Patriot, who had ill-advisedly applauded the ambush slaying of Colonel William Young by Unionists near the Red River.

Joining the Union Army

Texas contributed two regiments and two battalions of cavalry to the Union Army. The largest regiment, about 500 men, was organized in New Orleans in November 1862. (Texas’s total free population in 1860 was 421,215.) Joining the Union Army late in the war became attractive to men with no great affinity for the Union because it had become pretty obvious by then that Texas Governor Sam Houston had been right when he said in 1860, “Let me tell you what is coming. After the sacrifice of countless millions of treasure and hundreds of thousands of lives, you may win [but] I doubt it. I tell you that, while I believe with you in the doctrine of states’ rights, the North is determined to preserve this Union [and] when they begin to move in a given direction, they move with the steady momentum and perseverance of a mighty avalanche; and what I fear is, they will overwhelm the South.” Because of his opposition to secession, Houston was removed from office. He turned down Lincoln’s offer to lead Union troops to retake Texas.

Mississippi’s only white Union unit was the 1st Mississippi Mounted Rifles. A newspaper ad placed by the recruiting station in Vicksburg told potential recruits of a $300 bounty and an abundant supply of good clothing and wholesome food. (Until June 1864 a Union private’s pay was $13 a month.) More than 600 men enlisted in the 1st Mississippi. Some only stayed long enough to collect a bounty before deserting, some taking their horse and gun with them. By enlisting after deserting from another unit, some of them collected the bounty more than once. The great majority of the 1st Mississippi’s officers were from the North. Some of its enlisted men had previously served in the Confederate Army. The role of the 1st Mississippi was to protect the Federal base at Memphis and conduct expeditions in Mississippi, Missouri, and Arkansas. It engaged a number of times in small-scale combat with Confederates.

Most of the whites in Arkansas who owned slaves owned only a few, and they lived in the southern and eastern lowlands. Arkansas seceded because there was widespread opposition to forcing states that seceded to rejoin the Union. Despite its relatively small population, the only Confederate states to provide the Union with more soldiers than Arkansas were Tennessee and North Carolina. In mountainous north-central Arkansas, the war degenerated into a no-quarter-given conflict between bands of unorganized individuals.

Possibly as a result of hostility to the Federal government stemming from their forced removal west of the Mississippi, leaders of the Indian Territory’s slave-owning Five Civilized Tribes signed treaties with the Confederacy. Indians opposed to the Confederacy who fled to Kansas joined a Union Home Guard, which fought mainly in the Indian Territory but also served in Arkansas, Kansas, and Missouri. The last Confederate general to surrender was a Cherokee, Stand Watie.

In late 1863, there was a failed attempt to create a Union army unit in mountainous North Georgia. This effort was renewed in 1864 with limited success despite the $300 bounty. Some of the men who were recruited formed Georgia’s only white Union Army unit, the 1st Georgia State Troops Volunteers. This battalion of about 200 men was organized to guard the railroad from Chattanooga to Atlanta. It was deemed utterly useless and disbanded after some of its men fled rather than defend Dalton when Confederate troops sought to retake the city.

Some of the men who were recruited in North Georgia were enrolled in Union Army units in Tennessee. Nearly half the men in the 5th Tennessee Mounted (Union) Infantry were Georgians. Eight poor North Georgia farmers on their way to Cleveland, Tennessee, to join the 5th Tennessee were intercepted near the state line by Confederate guerillas and shot.

The men belonging to the Union’s 1st Louisiana Battalion Cavalry Scouts were among the troops Union Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks commanded in the Union’s failed Red River campaign. A New York soldier described the Loyalists who came in from the swamps and piney woods to take the oath of allegiance. They looked, he said, more like ragamuffins than men, clothed in every style of garment from the soiled coat of the gentleman to the hunting shirt of a backwoodsman or a full Confederate uniform. Reportedly, they “entered the residences of planters, carrying off whatever they needed or could appropriate, and in many instances offering violence and insults.” After Banks withdrew from Alexandria, the personal property of many Unionists was destroyed and their homes burned. Some Unionists were also murdered.

The 1st Alabama Cavalry

Pro-Union sentiment in Alabama was strongest in Winston County, a mountainous North Alabama county that in 1860 had 14 families who collectively owned 122 slaves and 637 families who owned none. A stronghold of Andrew Jackson Democrats, it began to call itself the “Free State of Winston” after the war began. Indicative of the strength of Unionists, who were often called Tories, is the fact that a pro-Union candidate in Winston won election to the secession convention by a vote of 515 to 128.

Most of the representatives to the secession convention from North Alabama voted against secession. Some refused to sign the ordinance of secession. During the war several prominent North Alabamians fled behind Union lines, which as early as 1862 extended into North Alabama. Others were prevented from going over to the enemy by being arrested for treason. Winston County’s delegate to the state’s secession convention was briefly jailed for treason because he was so outspoken in opposing secession.

When Union troops first appeared on the scene in 1862, North Alabama Unionists began recruiting troops for the Union from among the thousands of men hiding in the mountains of North Alabama either because they were deserters from the Confederate Army or to avoid being conscripted into it. A Peace Society organized behind Union lines helped elect a new governor of Alabama in 1863. By 1864, North Alabama Unionists were already discussing reconstruction

During the war, as many as 10,000 Confederate deserter and loyalist bands roamed and pillaged throughout North Alabama. Confederate deserters were also numerous in Unionist southeastern Alabama. Pillaging by loyalist and secessionist bands and Federal troops hurt the Confederacy by causing some North Alabama soldiers to desert the Confederate Army to go home to protect and support their families. William H. Smith, a future Reconstruction governor of Alabama, sought to escape conscription by serving in a civil office. After fleeing behind Union lines to escape arrest, he recruited Southerners for the Union.

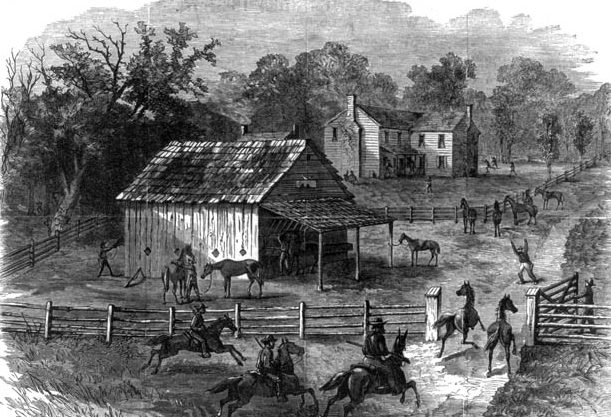

The 1st Alabama Cavalry, Sherman’s headquarters escort during his march through Georgia, was formed first in 1863. Companies of the 1st Tennessee and Alabama Independent Vidette Cavalry were organized in Alabama and Tennessee. (There was also a Confederate 1st Alabama Cavalry.) The majority of the unit’s men were Alabamians. The commander of the 1st Alabama, George E. Spencer, a New York-born lawyer, was serving as a captain on the staff of Union General Grenville M. Dodge when he requested a transfer to the 1st Alabama Cavalry Regiment. He was granted the transfer and promoted to colonel.

Various Union commanders, including Sherman, complimented the men of the 1st Alabama on their scouting ability. Their prowess as merchants of terror was recognized by both friend and foe. Union Colonel Oscar L. Jackson, commander the 63rd Ohio Regiment, said that the Alabamians “behave like robbers and marauders,” and in his diary he recounted a dispute with a 1st Alabama cavalryman who had entered a house intending to pillage and rob it. According to Jackson, the man was throwing out the contents of a bureau while the home’s women and children were frightened and crying. Jackson ordered him to stop. “This cavalryman,” said Jackson, “answered me a little short when I spoke to him and as he passed me I helped him out the door with my boot.”

The behavior of the 1st Alabama as it made its way to Milledgeville, Georgia, led Union Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard, who was apparently unaware that Sherman had ordered the 1st Alabama to burn the countryside, to write Spencer: “The major-general commanding directs me to say to you that the outrages committed by your command during the march are becoming so common, and are of such an aggravated nature, that they call for some severe and instant mode of correction. Unless the pillaging of houses and wanton destruction of property by your regiment ceases at once, he will place every officer in it under arrest, and recommend them to the department commander for dishonorable dismissal from the service.”

Union Maj. Gen. Ormsby Mitchel likewise complained in a report to Washington that lawless vagabonds and brigands connected with his army were “committing the most terrible outrages—robberies, rapes, arson, and plundering.” Mitchel said he was not responsible for these outrages because, since his line of posts extended more than 400 miles, he could not give personal attention to all his troops. Where he was, everything was in perfect order. Elsewhere, robberies, rapes, arson, and plundering took place. He asked for the authority to hang the perpetrators.

Saving Southern Unionists From Execution

The risk to a Southerner who donned a Federal uniform of blue was illustrated by the capture of two companies of the 1st Middle Tennessee Cavalry, which was raised in North Alabama. Acting as guides, these companies and some of the 1st Alabama’s men accompanied Colonel Abel Streight on one of the most inept raids of the Civil War. His men unwisely mounted on balky mules, Streight crossed North Alabama with Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest in hot pursuit. Forrest caught up with them near Rome, Georgia, and many of Streight’s men could not be awakened to do battle with the Confederates. Then, hoodwinked by Forrest into believing he was outnumbered, Streight surrendered to a much smaller force.

Alabama Governor John G. Shorter demanded that the Alabamians captured by Forrest be turned over to his state to be tried for treason. They were, he complained, guilty not only of levying war against their state, but of instigating slaves to rebel and of committing rapes and destroying property. They could not claim, as could citizens of border states remaining in the Union, that they were subject to the conflicting claims of hostile governments. They had voluntarily and openly betrayed their state. Therefore, they were not entitled to the privileges of prisoners of war. Union Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, who viewed Shorter’s demand as a violation of the agreement between the two nations relative to prisoners, responded to the threat by ordering that 800 Confederate prisoners be selected and held as hostages for the safety of the loyal Alabamians, thereby saving them from the hangman’s noose.

Winning the War, Losing the Peace

In 1865, despite Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick’s efforts to prevent it, the 1st Alabama burned Barnwell, South Carolina. According to Confederate Colonel Charles C. Jones, “The conduct of Sherman’s army and particularly of Kilpatrick’s cavalry and the numerous parties swarming through the country in advance and on the flanks of the main columns during the march from Atlanta to the coast, is reprehensible in the extreme. The Federals on every hand and at all points indulged in wanton pillage, wasting and destroying what could not be used. Defenseless women and children and weak old men were not infrequently driven from their homes, their dwellings fired, and these noncombatants subjected to insult and privation. The inhabitants, white and black, were often robbed of their personal effects, were intimidated by threats—and occasionally were even hung up to the verge of strangulation to compel revelation of the places where money, plate and jewelry were buried, or plantation animals concealed—horses, mules, cattle and hogs were either driven off, or were shot in the fields, or uselessly butchered in the pens.”

In March 1865, the 1st Alabama finished the war in North Carolina skirmishing with Confederate cavalry led by Generals Wade Hampton and Joe Wheeler. After the war, Spencer settled in Alabama and won election to the United States Senate. It is fair to say that few if any former Confederates voted—or were even allowed to vote—for Spencer. Henceforth, the struggle would move from the military to the political realm, and conservative “redeemers” ultimately would reclaim the region for the former slave owners and their supporters. In a sense, Southern Unionists helped win the war, only to lose the peace.

One of the more interesting events took place in Winston County Alabama when they attempted to secede from the secession in 1861. Although not successful, it sparked conflict among the pro and anti factions during and after the war. For an century after, Winston County was the only area that sent Republicans to the state legislature.

The Constitution of the Confederate States of America was largely copied from the US one, but one notable difference was that it explicitly outlawed secession.

The author is wrong about the term “bushwhacker.” It was actually applied to Unionists who lay in wait to ambush Confederates. Confederate supporters in Union-occupied (or claimed) areas were guerrillas, a term that came from Europe. This is made clear by documentation by people of the time. Guerrilla warfare is legitimate, bushwhacking is not as it occurred mostly in Union-occupied areas where there were organized Federal units.