By Charles Whiting

On Monday, May 21, 1945, men of the British 51st Highland Division were busy screening Germans and foreign nationals, mainly displaced persons attempting to go west over a small bridge near newly conquered Bremervoerde, Germany. They were on the lookout for war criminals and members of Himmler’s SS, who were categorized as “automatic arrests” if located.

Screening was a boring job, but was better than being in combat—something that had been their lot right up to two weeks before. So, bored or not, they did their job conscientiously.

Some time that day the soldiers on the little bridge spotted three men in civilian clothes who seemed to be hesitant about crossing. They stood out immediately, not only because of their hesitancy but because some of them were obviously soldiers in civilian clothes. The British troops speculated that they might be SS. It was, however, the third man of the trio who caused the Jocks to eventually stop them. He was small and skinny, and nothing about him caught the attention of the British. He did not even appear especially soldierly, save for the black eye patch he wore over his right eye. It made him look like a performer from some third rate amateur drama group.

The trio’s papers were examined and they seemed okay. Still, something did not seem quite right about the man with the black eyepatch, named, so he said, Hinziger. They asked more questions. It was then that the biggest of the trio made his mistake. He started to shout and threaten. That was enough for the men of the Black Watch, who had been fighting the Germans since the Battle of El Alamein in 1942. They arrested all three of them.

The trio was sent to a British Army holding camp for suspects at Barnstedt, 10 miles from the British 2nd Army headquarters at Luneburg. Here they were stripped and searched for anything incriminating, including what the guards there called “SS cough drops,” or suicide pills. Nothing was found. Thereafter, they were questioned under the leadership of the camp commandant, a captain codenamed Sylvester, of the Reconnaissance Corps.

In the end Hinziger’s nerve broke. He proudly told a British sergeant, “I am Reich Minister Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS, and I want to talk to Eisenhower.” He added that he had a letter for Field Marshal Montgomery, head of the British Army in Germany.

“And I’m Winston Churchill!” the British noncom quipped in cynical disbelief. All the same, Sylvester took Hinziger’s claim seriously. At that time, except for Himmler and Martin Bormann, Hitler’s secretary, all the top Nazis had been accounted for in the West. The two were assumed to be still on the run. Sylvester called Colonel Murphy, 2nd Army’s Chief Intelligence Officer, and was told to bring Hinziger in.

The final day in the life of the man who had once terrorized Europe had commenced.

Himmler, for he really was the Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler, was taken to a suburban house in the small town of Luneburg from whence the first of the current English royal family had originated 1,000 years before. There, he was stripped and given a blanket to wear because he would not put on a British uniform before being medically examined by a British doctor. Once more the medic was looking for SS cough drops. Again, the British doctor found no sign of the so-called lethal pill. While Murphy listened, Himmler ranted how he was too important to deal with “underlings.” He wanted to talk to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, supreme commander of Allied forces in Europe. From that, he went on to the need for the Western Allies and the defeated Germans to band together to fight against the Soviet Union before it was too late.

Watching all this, the British doctor started to have second thoughts. Himmler was too confident, too smug. It was as if he still had some last ace up his sleeve. He stopped the interrogation and asked Himmler to come over to the window where there was more light. He wanted to look into the German’s mouth. It was then that Himmler must have realized the game was up.

As the medical officer put his finger into Himmler’s mouth and spotted the cyanide capsule, Himmler bit down hard. The doctor yelled and pulled out his bitten finger in the same instant that Himmler swallowed the contents of the hidden capsule.

Immediately, there was chaos. Some British officers grabbed Himmler, turned the naked Reichsführer upside down, and immersed his head in cold water. Later, it was reported that the doctor threaded a needle through Himmler’s tongue to stretch it out so that he could reach down to his gullet and pull out what was left of the poison there. It was to no avail. Himmler died in agony. That was that. They threw a grey Army blanket over the corpse, posted guards outside, locked the door and went to report the sensational news to the higher authorities.

For 24 hours the British placed a security blanket over the whole affair. The body was photographed, examined in every way, and there was even a death mask taken. Then the time came to get rid of the scourge of German-occupied Europe. There was not going to be any post-war Himmler cult.

Under the command of a major, a Sergeant Major named Austen and four men were picked to bury the body in the woods of the so-called Luneburg Heath, where three weeks before the German Army had surrendered to Montgomery. It was a well-wooded, swampy area, once the favorite spot of pre-war weekenders on holiday from the big cities of northern Germany. Now empty, there were places enough for the burial party to inter the body far from prying eyes.

The man who had been responsible for the deaths of millions was buried in an unmarked spot like one might bury a stray dog. It seemed very fitting that Sergeant Major Austen had once worked for his local council in sanitation before the war. He was an expert in removing trash.

Thus ends the official account of how Himmler died—suicide by poison. For nearly 60 years only historians of the Third Reich had concerned themselves (if at all) with the manner of Heinrich Himmler’s death. All of them had been content to accept the British Army’s account that he had died in captivity by his own hand. That was until May 2005 when a minor book by an obscure historian appeared in London. It was Himmler’s Secret War, written by Martin Allen, an Englishman.

In the last few pages of his book, Allen, from southwest England, maintained that he had discovered documents in the British national archive at Kew, near London, that indicated Himmler had not committed suicide. Instead, he had been murdered on orders from British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. The latter had discussed the assassination of captured enemy leaders (such as Mussolini) who “knew too much” with U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt before his death in April 1945.

The book aroused little interest and no British national daily would touch the story, although it would have made excellent copy and raised the sales figures tremendously. That was until the major British daily, The Daily Telegraph, broke the news on July 2, 2005, with a three-page story of its own investigation into the alleged assassination.

The Telegraph, which had daily sales running into millions, investigated Allen’s claims that he or his researcher had stumbled across documents which had been previously overlooked by other historians. And what sensational finds they were. In fact, they purported that with Churchill’s connivance and agreement, three key members of his entourage, including a minister in his cabinet and an Earl, had ordered Himmler murdered. Why? The supposed answer was because Churchill knew about the peace negotiations being carried out during wartime with Himmler, the master of terror and the scourge of European Jewry.

But the Telegraph had doubts. The newspaper commissioned an expert in forensic science, Mrs. Audrey Giles. She testified that although the paper on which these top secret documents were typed was genuine 1945 material—as was the typewriter used—the letterheads of these same documents had been created by a high resolution laser printer developed only in the 1990s. Moreover, the old typewriter of 1945 vintage had been used on the documents typed in two separate government departments—separated physically by thousands of yards. Hardly likely, naturally. In addition, the signature of one of the key figures had been traced in, first in pencil before the ink version had been used over the pencilled tracing.

Allen was called to account by the Telegraph. He said he was shocked. “I think I’ve been set up,” he told the reporter. “But I do not even know by whom. I was devastated.”

Immediately, the British National Archives at Kew went on the alert. How had these documents, if they were forgeries, been planted in the archives? Anyone who has used the facility knows that security there is tight. Then again, who would be interested at this time in attempting to blacken Churchill’s character (and indirectly that of Roosevelt) by planting these very incriminating documents in the archive for the innocent historian to find?

We may never know! Perhaps it is simply a continuation—for whatever reason—of that secret war that commenced so long ago. At that time, many famous and infamous international military and political figures were threatened and killed.

So, what does a death on paper—one that never took place—matter? One thing is certain—terrorism at the top, which started so long ago, is now here to stay.

Two days after the Telegraph’s sensational report, its main rival, the American-owned Sunday Times felt it had answered the last question at least. Allen, it maintained, had already been involved in one such forged document case.

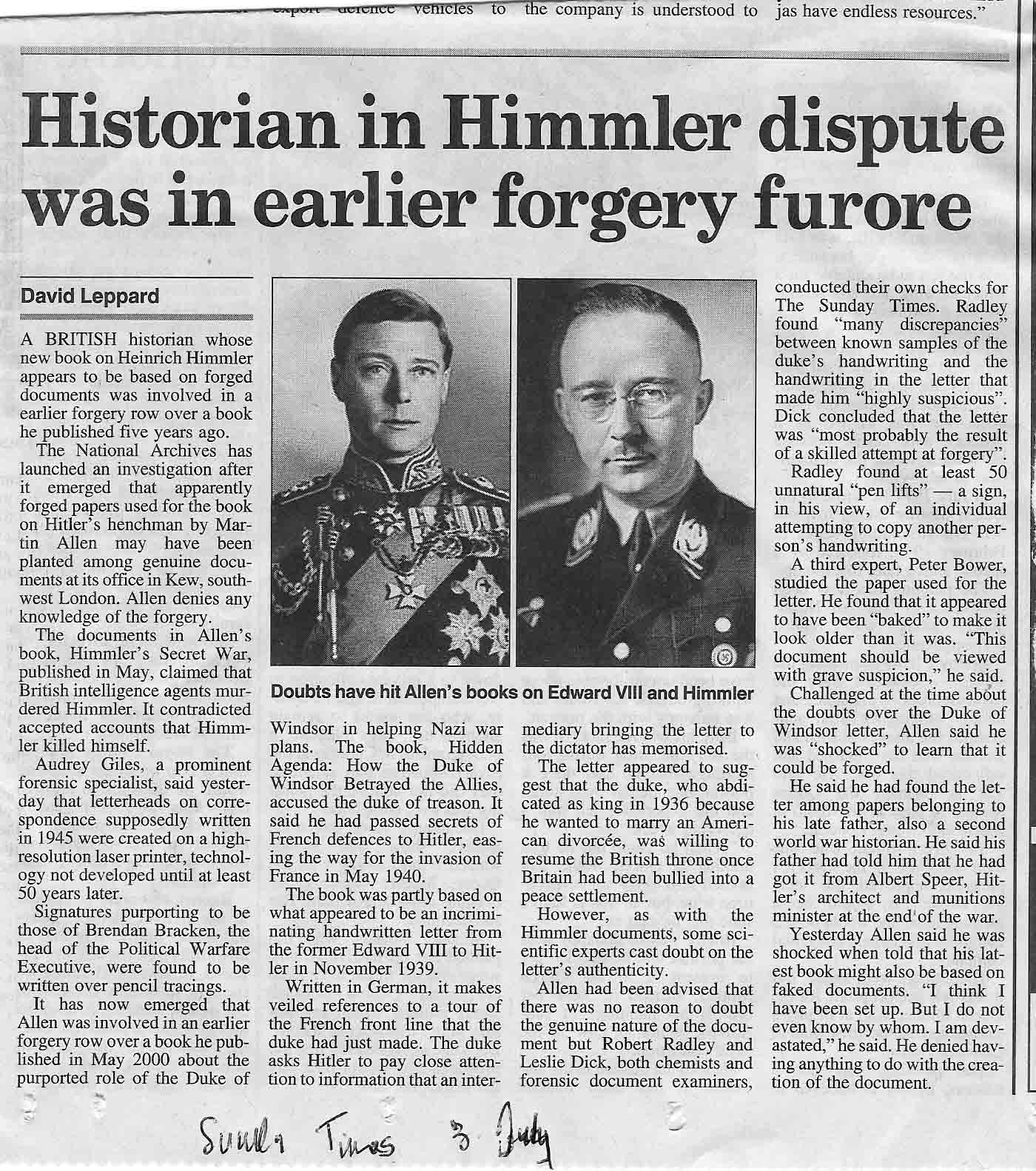

In his book, Hidden Agenda, published five years before, Allen had alleged that King Edward VIII, who had given up the British throne to marry American divorcee Mrs. Wallis Simpson, the future Duchess of Windsor, had betrayed military secrets to Hitler in May 1940. At the time, the king’s handwritten letter to Hitler in Germany, giving the military information, was examined by two forensic experts. They concluded it was a forgery. When Allen was confronted by the evidence of a forgery, he said he was “shocked.” The letter had been given to him, he stated, by his father, also a historian, who had received it from Albert Speer, Hitler’s minister of armaments. And that was that.

The jury is still out. No doubt, we are going to hear more about this forgery, which is likely to rival the most notorious set of forgeries of the post-war years, the “Hitler Diaries.”

Charles Whiting has written numerous books on topics related to World War II. He resides in England.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments