By Peter L. Boorn

When Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix was governor of Cilicia in 95 bc, he received an embassy from the Parthians. “One of the ambassadors, a Chaldean soothsayer, studied Sulla long and intently and finally proclaimed, ‘This man must, of necessity, become the greatest in the world,’” wrote Greek historian Plutarch. This prediction had a profound effect on Sulla, who already was convinced that his own night dreams were a faithful guide to an ever-expanding destiny. Seventeen years later, just two days before his death, Sulla noted in his memoirs that the Chaldean also had prophesied that the Roman governor would die at the pinnacle of his good fortune.

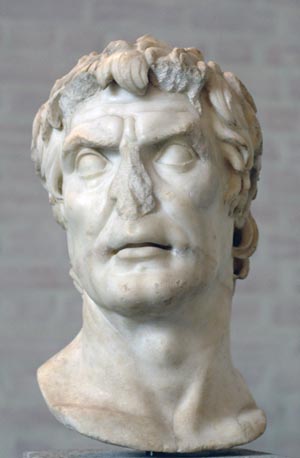

Sulla was born of a noble but impoverished family in 138 bc. Until he was 31 years old, he lived a life of debauched penury, renting cheap lodgings in Rome and always consorting drunkenly with actors, musicians, dancers, and comics. His vices remained with him until he died. Plutarch, who became a Roman citizen, gives a vivid physical description, emphasizing Sulla’s shock of golden hair, his fierce blue-gray eyes, and a face that was covered in coarse red blotches set against pale white skin.

Cornelius Sulla Felix

The first turning of Sulla’s fate came in 107 bc when he inherited two fortunes in rapid succession. One came from an aging mistress, and the other came from a stepmother who adored him. Armed with this lifeblood of politics, Sulla embarked on a late career in the Senate. In 107 bc, he became quaestor to Rome’s foremost general, Gaius Marius.

At the time, Rome was at war with the Berber king, Jugurtha of Numidia, in what is now northern Algeria. Romans had bungled the war, which began in 112 bc. This was because Jugurtha not only had acquired considerable knowledge of Roman tactics, organization, and discipline as a mercenary cavalry commander under the Romans in Spain, but also because he took advantage of the fact that anyone in Rome could be bribed.

When an army invaded Numidia circa 110 bc, Jugurtha bribed several centurions to throw the battle. The Berber king then defeated the army in battle with his light cavalry.

When a frustrated Rome gave Marius the supreme command, Jugurtha had joined forces with his father-in-law, Bocchus, the king of Mauretania, in modern-day Morocco. When Sulla arrived in Africa with a formidable complement of cavalry, he was inexperienced and ill disciplined in the art of war, noted Roman historian Gaius Sallustius Crispus, known as Sallust. “Although he was without previous experience and untrained in war, [he] soon became the best soldier in the whole army,” wrote Sallust.

Sulla put his hedonistic ways aside for a time and adopted an intensely practical concentration, according to Sallust. Yet Sulla’s sordid past also worked to his advantage because he was able to relate to the common soldiers. He conversed with them in a serious or jocular manner as circumstances dictated. He did this whether in the works, on guard, or on the march.

Marius defeated Jugurtha in several minor battles. The defeats compelled Jugurtha to resort to guerrilla tactics, which deeply frustrated the Romans, who were in need of a final victory. Further complicating the situation, Jugurtha had fled Numidia to seek refuge with Bocchus in Mauretania.

The Romans needed a quick resolution to the conflict in order to meet a major threat from the north. The Cimbrian War, which began in 113 bc, marked the first time that Italia and the city of Rome had been threatened since the Second Punic War. As the war progressed, the approach of the Cimbri and Teutones had put Rome’s northern front under tremendous pressure. These two Germanic tribes, which originally hailed from Jutland, numbered approximately 500,000 people.

At that point, Sulla proposed an audacious plan. At considerable risk to himself, Sulla offered to negotiate with Bocchus for the surrender of Jugurtha in exchange for the western part of the latter’s domain. Bocchus debated whether he should turn over Sulla to Jugurtha, but ultimately the Roman’s extraordinary luck prevailed. Jugurtha was led in chains to Marius. He was then taken to Rome where he was paraded in triumph. He was then placed in a pit under the Tullianum in Rome where he died of starvation in 104 bc.

The capture of Jugurtha marked the beginning of a falling out between Sulla and Marius, both of whom were supremely ambitious. Even though Marius received official recognition and a triumph for ending the war, it was widely known that Sulla had brought resolution to the conflict. A period coin shows Jugurtha kneeling in chains before Sulla, who is on a raised seat. As Sulla looms over Jugurtha, Bocchus offers him an olive branch.

At that time in Rome, the people were in a panic because the Cimbri and Teutones seemed unstoppable. Marius received supreme command of the Roman forces, and he chose as his co-consul Quintus Lutatius Catulus. Marius selected Catalus more for his malleability than his military skills for Catalus had a reputation as a poor general. Marius’s army shadowed the Teutones, and Catulus’s army observed the Cimbri. Sulla initially served as legate to Marius, but he swiftly realized that any independent move he might make would be checked by his jealous commander. For that reason, Sulla arranged to be transferred to Catulus’s army.

Marius annihilated the Teutones at the Battle of Aquae Sextiae in 102 bc. Marius and Catalus joined forces to confront the Cimbri on July 30, 101, near the settlement of Vercellae in Cisalpine Gaul. At Vercellae, Marius commanded the left wing, Catalus the center, and Sulla the right. Sulla’s wing was composed of both Roman and allied cavalry.

The reflection of the rising sun on the sea of Roman armor was so overwhelming that the Cimbri believed the sky was on fire. As they stood riveted in awe, a great cloud of dust enveloped their army, as well as that of the Roman left and center. The Cimbri cavalry hesitated, whereupon Sulla charged and routed them. The fleeing Cimbri cavalry subsequently disrupted the densely packed Cimbri infantry. The Roman infantry then waded into the disordered enemy infantry and hacked it to pieces. The two victories removed the threat posed by the Germanic tribes.

Once again, Marius received the honor of a triumph. Yet it was obvious to many that the foundation for the victory at Vercellae was the masterful performance by Sulla and his well-led cavalry.

At that time in Rome two powerful political factions existed: the Populares and the Optimates. The former relied on the support of the plebeians, while the latter derived its power from the affluent caucus that dominated the Senate. Marius threw in his lot with the Populares, and by means of bribery, riots, and assassinations was elected consul an unprecedented sixth time in 101 bc.

As for Sulla, he became governor of Cilicia in 96 bc. While serving in that capacity, he repulsed a reconnaissance-in-force by the king of Armenia. When he returned to Rome in 92 bc, Sulla joined the Optimates.

Marius, who was a far less skillful politician than he was a soldier, managed to offend both factions during his sixth consulship. During a coup in 99 bc three consular candidates were murdered and widespread rioting erupted. In response, the Senate issued the Senatus consultum ultimum, a decree enabling the appointment of a dictator for a short term to resolve an emergency. This gave Marius the power he needed to crush the rebellion.

Sensing that his political position was untenable in the aftermath of the rebellion, Marius undertook voluntary exile. He journeyed to the east, stating that he wished to honor a vow he had made to the goddess Bona Dea, according to Plutarch.

At that point, the tide of political fortune flowed in favor of the Optimates. But by 91 bc the Populares gained complete control of the courts and appointed a wealthy politician, Marcus Livius Drusus, as tribune. Upon his appointment, Drusus extended citizenship to the entire population of Italia. The Senate immediately annulled this legislation and conspired to have Drusus assassinated.

When the Italians heard the news they “decided to revolt from the Romans altogether and to make war against them with all their might,” according to Greek historian Appian. Thus began the Social War of 91-88 bc, which was caused by resentment among Rome’s allies who were aggrieved because they were denied citizenship even though they had shed blood for the republic.

The Italians raised 100,000 troops and established the rival state of Italia. Both sides fielded armies that were virtually identical in composition. At one point, Rome came dangerously close to defeat. With its forces depleted, Rome was forced to conscript slaves to replenish its armies.

Sulla led a successful campaign in southern Italia that overwhelmed enemy strongholds and defeated the forces sent against him, covering him in glory. Meanwhile, other Roman forces stabilized the situation in the north.

One of Sulla’s key victories occurred at Nola, just east of Naples, where he defeated an army of Samnites and Gallic auxiliaries. He then conducted a successful pursuit in which his forces killed 3,000 of the enemy.

The garrison of Naples was only willing to open one gate to the retreating rebels in an effort to reduce the chance that Sulla’s troops, who were following closely on their heels, could rush in behind the refugees. This enabled Sulla’s troops to slaughter 20,000 more enemy troops outside the city walls.

In the aftermath of his victory at Nola, Sulla was awarded the Grass Crown, the highest decoration that Rome bestowed on a general. The Grass Crown was given to a commander who had rescued an army that was in danger of capture or annihilation. Only seven other individuals received the Grass Crown in the entire 482-year history of the republic.

While the rebellion was winding down, Mithridates IV “The Great” of Pontus in Asia Minor took the opportunity to invade Rome’s client states. To the delight of the commoners, Mithridates massacred thousands of tax gatherers and money lenders. After clearing the Romans from Asia Minor, Pontic forces advanced into Greece.

The Roman Senate entrusted Sulla with prosecuting the war against Mithridates, but Marius derailed those plans. Marius returned from Africa in 88 bc with an army and entered Rome. To obtain command in the east, Marius resorted to bribery. This touched off Sulla’s First Civil War.

Sulla subsequently received orders to relinquish command to Marius. At that point, though, the Marian reforms rebounded on their maker. Sulla not only refused, but he undertook an action so audacious that all but one of his senior commanders refused to join him. Confident in the loyalty of his troops, Sulla turned his six legions back toward Rome. No other Roman commander had ever dared do that.

Sulla also returned to Rome in 88 bc. He encountered chaos and disorder, but there was no fighting. Marius, who had gone into hiding, was declared an enemy of the people. So eager was Sulla to finish his diplomatic business with Mithridates that he appointed as consul L. Cornelius Cinna, of whom he was suspicious, to carry on the war so that he could return to Greece.

At that point, Marius came out of hiding, raised an army of slaves, and cooperated with Cinna to capture Rome. The Senate reversed the decree outlawing Marius, who turned his troops upon the city. For five days Rome endured a reign of terror.

When Cinna and Marius declared themselves co-consuls in 86 bc, it was Sulla’s turn to be outlawed. His property was seized and his family fled for their lives. This was the last act of 70-year-old Marius who, 17 days into his seventh consulship, died in his bed of natural causes.

Having returned to Greece, Sulla again turned his attention to defeating Mithridates. Advancing into Boeotia, he defeated two of Mithridates’ generals. He then besieged and sacked Athens. He then vanquished another Pontic army at Chaeronea in 86 bc. The following year Sulla crushed yet another Pontic army at Orchomenus. With Greece lost, Mithridates sued for peace in 85 bc.

Once order was restored in the east, Sulla composed a letter to the conscript fathers informing them that he would soon return to Rome to punish those who had acted against him, but that those who were innocent had no reason to be fearful.

A cowed Senate attempted negotiation, but Cinna and his colleague C. Papirius Carbo prepared for war. In the spring of 84 bc, Cinna tried to embark his army for Greece, but his soldiers mutinied and murdered him. In 83 bc Sulla crossed the Adriatic Sea from Patrae in western Greece, landing at Brundisium. Although the road to Rome was open, Sulla decided instead to consolidate his position and raise additional troops.

The consuls for 82 bc were Carbo and the 26-year-old son of Marius, known as Marius the Younger. Between them they raised large numbers of troops to prosecute what would be known as Sulla’s Second Civil War.

Sulla routed Marius the Younger at the Battle of Sacriportus. The youthful commander eventually killed himself. After securing Rome, Sulla marched north where he met Gnaeus Papirius Carbo in battle at Clusium. Clusium proved to be an indecisive affair, but afterward Carbo’s men became demoralized. As a result, Carbo himself lost heart. He abandoned his men to their own fate and fled to Sicily where he was later slain.

The stage was now set for the final act of Sulla’s Second Civil War. A huge army of Samnites and Lucanians, numbering upward of 70,000, descended on Rome. On November 1, 82 bc, they clashed with Sulla’s army north of the city at the Colline Gate. Sulla’s troops arrived following forced marches. Sulla and Marcus Licinius Crassus commanded the legions of the left and right wings, respectively.

Although his troops were greatly fatigued, Sulla attacked. Ferocious fighting ensued that lasted well into the night. Although Sulla was driven back in disorder against the city wall, Crassus prevailed. He led one of his units around the flank of the Samnite army and attacked it from behind. This enabled Sulla to launch a fresh attack and clinch the victory.

Sulla showed no mercy. The following day his army butchered 4,000 Samnite prisoners within earshot of the assembled Senate. The proscriptions that followed were more sustained, widespread, and thorough than those of Marius. The names of 6,000 victims were published in the official list. The list included the names of 90 senators, 15 of consular rank, and 2,600 equestrians, according to Appian. The property of those on the list was seized in order to provide allotments for 120,000 discharged soldiers.

To maintain order in Rome and to protect himself, Sulla recruited a servile version of the future Praetorian Guard that he named the Cornelii. He freed 10,000 virile slaves of the proscribed, armed them, and stationed them within the city walls.

Sulla was elected dictator for life in 82 bc and all his acts were ratified in advance. He was, in all but name, a king. He made no attempt to solve the problems that beset the nation. His policy was purely reactionary: it was done to restore the Senate to its ancient authority by suppressing all possible dissent.

Sulla’s almost preternatural intuition is exemplified by an incident in which then 18-year-old Gaius Julius Caesar ran afoul of the dictator and was nearly proscribed. When Caesar’s family and the Vestal Virgins appealed to Sulla for his salvation, the dictator relented. “This man, for whose safety you are so extremely anxious, will, someday or other be the ruin of the party of the nobles, for in this one Caesar, you will find many a Marius,” said Sulla.

In 79 bc, Sulla abdicated his dictatorship confident in the loyalty of the Cornelii. The following year he died suddenly at the age of 60 just as he was on the verge of completing his memoirs. Engraved on his tomb were some of his own words: “No friend has ever served me, no enemy has ever wronged me whom I have not repaid in full.”