By David H. Lippman

It was nearly over. Since Singapore had fallen to the Japanese on February 14, 1942, the Allied forces defending the Dutch East Indies had battled against a Japanese pincer-like movement, which consisted of aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers, aircraft, and well-trained “Special Naval Landing Forces”—Japan’s version of American and British Marines. All of these men and weapons were powerful enough in their own right, but deadly when combined.

Against this, the Allies mustered a poorly-coordinated and badly-armed collection of contingents from Britain, the United States, Australia, and the Netherlands. Under Field Marshal Lord Archibald Wavell, Dutch native infantry, outdated Dutch and Australian fighter aircraft, American submarines armed with defective torpedoes, and a small group of inchoate American, British, Australian, and Dutch warships under Dutch Rear Admiral Karel Doorman struggled to defeat the onslaught.

Now it was proving impossible. Determination and valor were not enough. Doorman was killed when his flagship was sunk in the Battle of the Java Sea on February 27, along with another light cruiser and four destroyers. With the two heavy cruisers, HMS Exeter and USS Houston, damaged as well, there was nothing to stop the huge Japanese force from landing in Java. Lord Wavell had no choice but to dissolve his multi-national command.

Facing defeat, the senior British and American admirals informed their Dutch hosts and nominal superiors that they were pulling their ships out, too.

Doing so would not be easy for the heavy cruisers. Exeter’s engines suffered severe damage at Java Sea. Houston had taken a bomb hit earlier that had burned out its No. 3 after 8-inch gun turret, leaving the gunhouse in position, but the shell elevator and handling rooms a blackened hole. Houston’s passageways were filled with wreckage, clothing, shattered glass, scattered clothing, and bric-a-brac from the concussion of its own guns. Hoses and pipes leaked into passages. Even all-important searchlight lenses had been blasted to fragments. The guns needed replacement. Ammunition in all categories was short. The long-service crewmen despaired at seeing the condition of a warship that had once carried President Franklin D. Roosevelt on his fishing vacations.

Worse, those crewmen were exhausted. Nobody, including Capt. Albert H. Rooks, had slept in 30 hours or changed clothes in three days, constantly answering the General Quarters bugle to fend off air and sea attacks. As Houston tied up at Tandjung Priok after the disastrous battle, there was still no rest, as sailors man-hauled heavy 8-inch shells from the crippled lockers of turret 3 to the forward guns, and others fueled the ship.

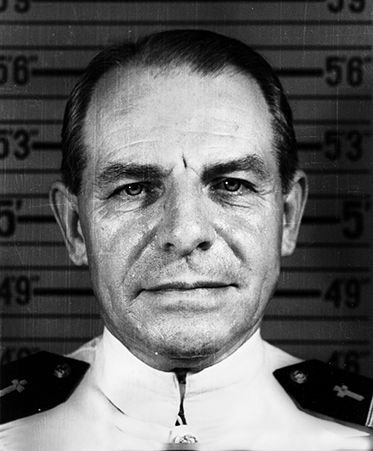

Conditions were much the same on HMAS Perth, a light cruiser that had seen action under her tough skipper, Captain Hector “Hec” Waller, from the war’s outbreak in 1939. Her sailors were now veterans from battles in the Mediterranean, and the ship was undamaged, but like Houston, was short on fuel and ammunition. To make matters worse, Waller was suffering from gall bladder trouble.

Now both ships had to flee Java before Japanese invaders came ashore. Their ultimate destination would be Australia. However, supplies were short. Even though the Dutch East Indies were a major oil producer, Java’s tanks were in the mountains, and the native workers had fled their posts. Dutch naval base workers were more interested in using explosives to deny the use of their facilities to the Japanese than servicing the Allied ships.

Worse, the Dutch Navy only offered limited supplies from their shore tanks. Perth fueled 300 tons, half her capacity, while Houston, as a larger ship, had enough fuel to reach Australia if she was careful on consumption.

Problems continued. Javanese fuel was high-quality even though unrefined, but not up to the standards of the U.S. and Royal Navies—it easily jammed in tanks. Both ships needed everything from ammunition to life rafts to toilet paper. The first they found: wooden and copper life rafts. Perth alone took 24 on board. Crewmen raided a canteen and found vast supplies of whiskey and cigarettes in boxes marked “Victualling Officer, Singapore.” The Japanese had taken Singapore, so the sailors took them.

However, Players cigarettes could not be fired at Japanese warships and aircraft. There were no 8-inch shells on hand for Houston or 6-inch rounds for Perth. Houston had fewer than 50 rounds left for each of her working guns. Perth had 20 for each of hers. The two ships would have to go with what they had.

Commodore John Collins of the Royal Australian Navy, the senior Anglo-American officer on the scene, told Waller and Rooks their best way out of the closing trap was to head west for the Sunda Strait and go through it by night, fueling at Tjilatjap on Java’s south shore. From there, they could make a high-speed run to Australia. They had a good chance as the Japanese lacked radar.

The crew members of the two ships, battered by omnipresent battle, fatigue, and death, were delighted to hear they were going to withdraw to Australia. “Our spirits were high. We thought we were going home,” said Houston Marine Private Lloyd Willey later. Lieutenant Leon Rogers, who commanded an anti-aircraft gun said, “Thank God, we’re going to get out of this Java Sea.” Houston’s Chief Engineer Lt. Cdr. Richard Gingras said, “You know, I had no hope that we would ever get away from all this, but now I think we’ve got it made.”

However, sailors can be superstitious, and there were plenty of bad omens. On Perth, the portrait of the Duchess of Kent, who had renamed the cruiser into Australian service in 1939, fell to a splintering crash from the wardroom bulkhead to the deck. The ship embarked a second chaplain, which was considered “lethal” by the Bluejackets. Red Lead, Perth’s mascot cat, tried to jump ship three times. Houston’s tried only once.

Nor were some officers as optimistic. Rooks briefed his senior officers, saying “We’re getting out of the bottleneck,” telling them that the latest intelligence had the Japanese 10 hours away from the strait. Senior aviator Lieutenant Thomas Payne said otherwise. He had flown his SOC Seagull biplane on a recce mission over that presumed route and seen a Japanese cruiser.

Payne was right. Dutch PBY Catalina seaplanes had seen the same Japanese ships, but because of the poorly-coordinated and disintegrating ABDA command structure, that information never reached Rooks or Waller.

Lieutenant Walter Winslow, Houston’s junior aviator, lacking a plane to fly, wrote, “Perhaps it was best that none of us knew the awful truth.”

The Australians were less optimistic. Waller told his navigator, Lt. Cdr. J.A. Harper, that it looked as though the Japanese would land east of Batavia that very night. Harper called it unlikely that the convoy’s escorts would detach themselves from their charges to attack Perth or Houston. Waller agreed.

Promptly at 6:30 p.m. on February 28, the two cruisers shifted colors and steamed slowly out of the harbor entrance to avoid Dutch mines. Once past them, the warships cranked up to an economical 22 knots and headed west to the strait.

Waller announced over Perth’s tannoy (1MC to Americans): “We are sailing the Sunda Strait for Tjilatjap on the south coast of Java. Shortly, we will close up to the second degree of readiness. Air reconnaissance reports the strait is free of enemy shipping, but I have a report that a large enemy convoy is about 50 miles northeast of Batavia, moving east. I do not expect, however, to meet enemy forces.”

Waller’s words left his crew with foreboding and unspoken fears. Engineer Lieutenant Frank Gillan believed his ship had hit a dividing line between present and future and a decision had been made affecting his life and both ships’ crews.

With that done, Waller lay down on the deck. He told his Officer of the Watch, “Kick me if anything happens,” and fell asleep. Everyone loved and respected the unpretentious and courageous pipe-smoking skipper.

The exhausted crews of both ships manned their stations, steaming into the gathering dusk under clear skies and a full moon. Nobody noticed a small ship following them.

The small ship was the Japanese destroyer Fubuki, the world’s oldest tin can, right now one of many such tin cans escorting a convoy of 56 transports headed for west Java’s Bantam Bay. There were more: four heavy cruisers of Cruiser Division 7 (Crudiv 7), Kumano, Suzuya, Mogami, and Mikuma, all larger than the two Allied cruisers and armed with deadly “Long Lance” torpedoes, which outranged those on Perth. Houston lacked any torpedoes.

The Japanese ships were manned by crews well trained in night fighting. They were backed up by the small light cruiser Natori, also armed with Long Lance torpedoes. The overall boss was Rear Admiral Takeo Kurita, and his mission was clear: land Lt. Gen. Hitoshi Inamura’s 16th Army at Bantam Bay to conquer Java. This massive Japanese force, like an octopus, would scatter its arms to conquer key points in the Dutch East Indies.

And neither force knew about the presence of the other.

The Allies were the first to find out when Waller woke up from his power nap. Perth led Houston by 900 yards as the skippers followed their plan to cross the mouth of Bantam Bay and make for St. Nicholaas Point, the northern entrance to the strait. The bay, however, gave enemy ships somewhere to hide at night. “They could hide a battleship out there and we’d never see it until attacked,” said Houston Marine Standish.

Waller cranked up Perth to 28 knots. St. Nicholaas Point was five miles away. As the cruisers approached, a Perth lookout shouted, “Ship, sir, bearing green oh-vie.” Everyone on the bridge swung to look. Waller figured it was one of the remaining Dutch patrol boats on station. He had been told to be on the lookout for them.

“Very good,” Waller said. “Make the challenge,” he said. Perth flashed it on their Aldis Lamp, while Rooks and his bridge crew, looked on.

The unknown ship answered two green lamps. The signalmen said that was “UB,” which was not the Allied Night Recognition Signal. Former signalman Waller was always annoyed when proper procedure was not followed and ordered “Challenge again.” While he did, Houston’s turrets trained on the intruder.

The mystery ship heeled away, making smoke, showing full silhouette. It didn’t take recognition books to identify it as the Japanese destroyer Harukaze, escorting the transports. She raced into the bay, launching a red flare to warn her flock.

“Jap destroyer,” Waller yelled. “Sound rattles!”

Houston’s alarm bells summoned its crew to General Quarters, including Lieutenant Winslow, who was sleeping the sleep of exhaustion when they went off. Dazed and lacking an action station because his plane had been destroyed earlier, he dressed and sprinted for the bridge, figuring that his rank might be useful there. “We were desperately short of those 8-inch bricks,” he wrote later, “and I knew they were not being wasted on mirages.”

As the fugitive Allied cruisers passed Babi Island, firing off star shells, everybody discovered that they were in the middle of a gigantic convoy, surrounded by 27 transports, the heavy cruisers Mogami and Mikuma on distant cover, light cruiser Natori, and seven destroyers on immediate convoy cover. This detachment of the invasion force was commanded by Rear Admiral Kenzaburo Hara. It was an overwhelming collection of warships.

Incredibly, the Imperial Japanese Navy now committed one of its most inept performances of a war that was filled with such catastrophes.

First, despite the Japanese knowing the Allies were going to have their remaining heavy ships flee Java, they had not prepared for a night attack on their transports. Hara thought the two fugitive cruisers were fleeing Java in the opposite direction, to the east. The only ship between Batavia and Bantam Bay to head off the refugees was Fubuki. The remaining combatants were grouped in two columns to catch the Allied ships heading into Sunda Strait, not to guard the 27 transports, which should have been their primary mission.

Perth and Houston slipped by Fubuki, which sent out a warning, saying, “Two mysterious ships entering the bay.”

Another Japanese mistake—Hara and his staff thought the opponents were light or civilian vessels. Kurita, showing the weak battle instincts that defeated him at Leyte in 1944, held back his own cruisers and destroyers, leaving the battle to Hara. It was a “scramble of chaos and confusion,” as Japanese destroyer skipper Tameichi Hara (not related to the admiral or present at the battle) wrote later.

Into this careless situation Houston and Perth steamed, both ships’ officers finding 27 hapless transports open to destruction. If Doorman and his whole fleet had been there, with more ships and full ammunition loadouts, a great Allied victory could have resulted.

Instead, two battered Allied cruisers, deathly short on ammunition, manned by exhausted crews, were engaged. As U.S. historian Samuel Eliot Morison wrote: “They had run into an enemy amphibious force at its most vulnerable moment. But alas, they were so few and the time was so late.”

In the best traditions of their two navies, Houston and Perth attacked. “It looks like a trap,” Waller said. Houston could not shell Fubuki—she was in range of her useless No. 3 turret. At 11:14 p.m. Fubuki launched torpedoes that missed, then fled behind a smoke screen.

The two cruisers steamed past the merchant ships, still intent on escaping through Sunda Strait, Waller leading them on a starboard turn to unmask all batteries against the transports. The cruisers hurled ordnance at the parked freighters and landing ships.

Hara ordered his ships to head to the sound of the guns, but in no formation, his destroyers arriving in ones and twos. Houston logged: “Fight developed into a melee—Houston guns engaged on all sides, range never greater than 5,000 yards.”

The battle now descended into a fully-lit barroom brawl under the full moon, with Japanese destroyers attacking the Allied cruisers from their port sides.

Both sides were blasted. Harukaze took hits in her bridge, engine room, and rudder, killing three and wounding 15. A 5-inch shell blasted Perth’s forward funnel, rupturing a steam pipe.

As more Japanese destroyers attacked in groups of three, Waller turned Perth to the south, then looped back northeast, salvo-chasing. He told his gunner to fire at local control, at any available targets they could choose. Rooks did the same, finding doing so was impossible for his larger guns—he went back to main battery director.

Hara ordered his tin cans to use Japan’s best weapon—the night torpedo attack. Hatsuyuki fired nine fish at 11:40 p.m. at a range of 4,000 yards. They missed. Asakaze launched six torpedoes three minutes later. They missed. Winslow swore he saw the Japanese fish race under Houston’s hull. Apparently, the Japanese believed they were engaging battleships, so they set their torpedoes on lower depth.

A disgusted Hara ordered his destroyers to form up on his flagship, Natori, and sent in his heavy cruisers to take care of business with their ten 8-inch guns and 12 torpedo tubes each.

At 11:46 p.m., the immense cruisers—overweight by Washington Treaty standards— steamed into action with Mikuma’s Capt. Shakao Sakanami in charge. He decided that the best move was to sail parallel to the Allied ships and give them a full broadside of torpedoes and shells. One shell hit Perth’s hull near the waterline and started flooding. However, the six torpedoes launched at 11:49 all missed.

Dead ahead of the Japanese cruisers was Babi Island, and Sakanami nimbly turned his ships in a countermove to keep up with the enemy. Unable to find them, Sakanami’s ships lit up their searchlights—and caught each other in their beams.

Meanwhile, Houston, now desperately short of 8-inch shells, scored a near-miss on Mikuma at 11:55 that tripped the cruiser’s circuit breakers—she would have a luckless war—and knocking out her lights and main battery for five minutes.

Now the Japanese destroyers, having reloaded their torpedoes, raced in and Allied guns battered destroyer Shikinami.

The battle was a “fire-away Flanagan.” Houston took a blast to the forecastle that set the forward paint locker ablaze, providing the Japanese with an easy target.

The two Allied cruisers were now surrounded, without escape, and had no more ammunition. Gunnery Officer P.S.F. Hancox told Waller his men were firing using practice rounds. “Very good,” was all Waller could say, as he calmly issued orders. Perth fired star shells as well. With those gone, somebody asked what to do. A veteran sailor said, “Raid the potato locker.”

Waller made a looping port turn back to the southwest at full speed, hoping to outrace the attackers; Houston followed him. Though unorganized, the Japanese had more ships and ammunition, and soon surrounded the fugitives.

At 11:57 p.m., Mogami launched six torpedoes from her portside tubes at 10,000 yards. They missed. Instead, they hit the 8,160-ton transport ship Ryujo Maru, Inamura’s headquarters ship, where he and his staff had been watching the engagement with increasing annoyance. At 12:05 a.m. on March 1, Ryujo Maru suffered an underwater explosion that hurled Inamura and the 18th Army’s senior officers into Bantam Bay. Other ships sunk by Mogami’s misfired torpedoes were three transports and a minesweeper, which keeled over into the bottom of Bantam Bay, destroying tanks, automobiles, freight, and tons of equipment while drowning scores of Japanese troops. Not one of the hits came from an Allied ship. A later Japanese investigation could not determine which ship was responsible, as three of the destroyers added to the “friendly fire.”

Meanwhile, Houston damaged the tin cans Shizakumo and Harukaze. Japanese destroyers were now locked onto the Allied ships. Waller yelled, “For God’s sake, shoot that bloody light out!” An Australian machine-gunner did so, but the fugitives remained illuminated by Japanese flares and searchlights from Mogami and Mikuma.

It was a last stand now—a naval Thermopylae—with all chance of escape gone. Yet the exhausted crews kept on fighting. At 12:05 a.m., a destroyer torpedo hit Perth’s starboard side in her forward engine room and boiler room A. Perth lost speed and became sluggish.

“Christ, that’s torn it,” Waller said on the bridge. “Prepare to abandon ship.”

“Prepare to abandon ship?” asked Hancox.

“No. Abandon ship.”

As damage reports came in, Waller stayed calm—two more torpedo hits, one near the forward magazine for A turret, another under X turret. Waller’s officers urged him to leave, but he refused.

Hands clamped to the bridge railing, looking over his silent gun turrets, Waller ordered his officers off the bridge. He was never seen again, one of Australia’s finest fighting officers going down with his command.

Sailors took advantage of the extra copper and wood life rafts on deck to leap into the increasingly oily water. Japanese ships nudged toward Perth, firing shells at her as she “steamed out” into the deep, her “Battle Duster” snapping, fully illuminated by searchlights. Perth went down 9.5 miles northeast of St. Nicholaas Point at 12:25 a.m., taking 45 officers, 631 sailors, and four Chinese canteen staff, with her. There were 320 men floating in the water, staring at the sinking ship.

From astern, Houston’s sailors watched the scene in horror. Rooks gave up his plan to force his way around Toppers Island and turned to make the Japanese pay. “When Captain Rooks realized Perth was finished and escape was impossible, he turned the Houston back toward the transports, determined to sell his ship dearly,” Winslow wrote later.

What happened next was best described as “one of the most gallant (fights) in American naval annals,” by Samuel Eliot Morison. “Unfortunately no word of it, except the mere fact of her loss, was revealed until the war was over.”

Covered in searchlight beams, Houston used every weapon she had left to silence them—one Marine shot out a searchlight with his Springfield rifle.

Once again Sakiyama took a parallel course to the enemy ship and opened fire with his 8-inch guns and torpedoes. The ordnance was effective. Houston was hit in the aft engine room and the wardroom. The latter ruptured steam lines and killed everyone inside—the compartment was being used as a dressing station for wounded men. Another shell hit the No. 2 turret’s face plate just as powder was exposed for this ship’s 28th salvo. The hit was a dud, but sparks cooked off the powder, which forced Rooks to flood his forward magazines to prevent an explosion. Now both forward turrets were silent. All Rooks had left were his secondary 5-inchers, with both sides firing at point-blank range.

A Japanese torpedo hit Houston on the starboard side underneath the bridge. That did it. Up in the armored conning tower, Rooks summoned Marine Field Music (Bugler) Jack Lee, and said, “Bugler, sound Abandon Ship.” Lee did so, perfectly, into the 1MC.

Marine Private Lloyd Willey later recalled, “He never missed one beat on that bugle. It would have been absolutely beautiful if it had been anywhere else but that time.”

Winslow shook hands with Rooks and climbed down a ladder to the deck below, where he saw a shell hit where he had just been standing with his skipper. Rooks was hit by shrapnel in the head and upper torso. Ensign Charles D. Smith jabbed Rooks with two tubes of morphine, but it was too late. Rooks died in a minute. Smith covered him with a blanket.

The captain’s Chinese cook, Ah Fong, hired in Singapore, known to all as “Buda,” cradled Rooks in his arms and said, “Captain die, Houston die, Buda die, too.”

Commander David W. Roberts, the executive officer, took command of the burning, blackened, heeling ship. Even though Houston was headed for the bottom, the Japanese did not want to wait, firing torpedoes at her as late as 12:29.

Houston continued her roll to starboard, her bow dipping beneath the waves. Fearing that not all of Houston’s crew had gotten the word to abandon ship, Roberts ordered Signalman 2nd Class William Stafford to sound the bugle call again. He stood on his ship’s careening fantail blowing “Abandon Ship” as Houston went down.

All around were 368 survivors of the sinking, including Commander George Rentz, aged 59, the ship’s chaplain. A year short of retirement, he jumped off his raft, gave his life jacket to a shipmate, and said, “You men are young, with your lives in front of you. I am old and have had my fun.” He offered a prayer for his shipmates, swam off, was never seen again, and earned a posthumous Medal of Honor for his sacrifice.

Another survivor floating in the water was General Inamura, who spent 20 minutes on a piece of wood before being picked up by a boat and three more hours making his way to Bantam Bay. Once ashore, soaked from head to foot, he sat down on a pile of bamboo, exhausted.

Inamura’s aide, equally covered in oil and water, came up to his general to offer some of the humor often desperately needed in war. “Congratulations on the successful landing,” the aide said.

A Japanese Navy officer apologized to Inamura for sinking his ships. “Let Houston have the credit,” Inamura said, offering some of the chivalry also desperately needed in war.

Out at sea, all eyes were on the slowly sinking Houston, caught in the beams of Japanese searchlights. She was about to provide everyone watching with some of the defiance also often desperately needed in war.

Winslow described the scene perfectly: “After having been subjected to so much punishment, she should have capsized instantly. Instead, the Houston wearily rolled back on an even keel. With decks awash, the proud ship paused majestically, while a sudden breeze picked up the Stars and Stripes, still firmly two-blocked on her mainmast and waved them in one last defiant gesture. Then, with a tired shudder, ‘The Ghost of the Java Coast,’ our magnificent USS Houston, vanished beneath the sea.”

Author David Lippman resides in New Jersey and writes frequently on a variety of topics for WWII History.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments