By Bruce K. Campbell with Glenn Barnett

I was born in Los Angeles in 1924 and attended local schools. In high school I enrolled in ROTC and, when I could, I went skiing for fun. When I graduated from Los Angeles High School in 1942, the country was at war—and we all knew that military service was a patriotic necessity.

As I was not yet drafted, I enrolled at UCLA in the fall. Early in 1943, I joined the Enlisted Reserve Corps (ERC—today the U.S. Army Reserve). That way, when I was called up, I could choose the branch of the service that I wanted. Meanwhile, I continued with ROTC training.

My decision about which branch of the military to join was made one afternoon at the movies. The theater showed a “short” about the 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment. It was produced by John Jay, a well-known ski film photographer. Afterward, the theater manager announced that there were applications in the lobby. Since I loved to ski, I filled out the application, which also required three letters of recommendation.

The idea for an Army ski unit was born during the winter of 1939-1940 when outnumbered and outgunned Finnish soldiers on skis were able to blunt the invasion of the Soviet Army. At home, Charles Minot “Minnie” Dole, the founder of the National Ski Patrol System, strongly and repeatedly urged the War Department to form a unit of men specially trained for mountain and winter warfare.

In the early days of the war, Americans found themselves fighting in the jungles of the South Pacific and the deserts of North Africa. There wasn’t much need for ski troops. Dole, however, convinced the Army to establish a “mountain” unit similar to those in the Russian and German Armies. The armies of France, Italy, and others also had specially trained mountain units.

Training in a Mountain Unit

When I enlisted, none of my friends had ever heard of American ski troopers, so when I underwent orientation at Fort MacArthur in San Pedro, California, I was the only one assigned to Camp Hale in Colorado. As it turned out, I was one of the few southern California boys to join the ski troopers.

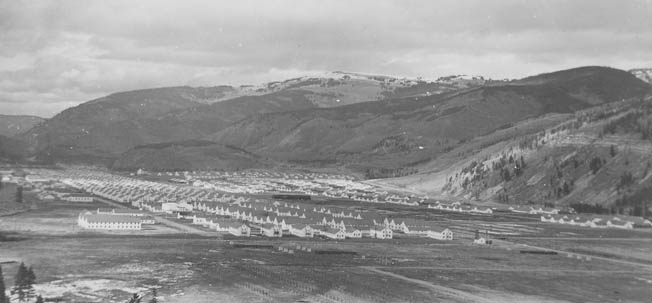

Camp Hale consisted of more than 800 whitewashed buildings—a real city—that had been hastily built in the summer of 1942. When I arrived on April 1, 1943, I was the only passenger to get off the train at Pando station adjacent to the camp. The station at Pando was about the size of a closet, and no one else was there. I thought it might be a cruel April Fools’ trick. Shortly, however, I was picked up by an Army jeep and driven a short distance to Camp Hale, my home for the next 15 months. There would eventually be more than 12,000 men and 4,000 pack mules and horses living there.

My first run at the 9,200-foot altitude left me exhausted. When I arrived, I was 6 feet, 2 inches tall and weighed 155 pounds. In the next nine months I put on 30 pounds, all muscle. Some of our instructors were famous skiers from the National Ski Patrol, college ski team coaches, and even some from Norway, Switzerland, Germany, and Austria who had left home to avoid Nazi tyranny. One Austrian who would join us later was Werner von Trapp of the von Trapp family, who were chronicled in the movie The Sound of Music. He proved to be very useful as an interpreter.

The first volunteers had already become the 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment and had initially trained on Mount Rainier near Fort Lewis, Washington; they had also been sent, in August 1942, to the island of Kiska in the Aleutians to evict the Japanese who had captured it and Attu Island as a diversion from their attack against Midway.

Attu had been recaptured after bloody resistance. Now it was Kiska’s turn, and the 87th was called upon to help retake the island. But the Japanese had secretly evacuated Kiska, so when 35,000 Americans and Canadians landed on the fog-shrouded island where no one could tell friend from foe the only casualties were from friendly fire and booby traps.

The new guys like me at Camp Hale were formed into the 86th Mountain Infantry Regiment; the 85th Mountain Infantry Regiment would be added as well, plus all the supporting units such as the artillery, engineers, quartermasters, medical personnel, and such. All together we would become the 10th Mountain Division. When the division was formed, our patch was designed. It consisted of crossed red bayonets forming the Roman numeral X on a field of blue.

Meanwhile, we trained and trained and trained. Most of the enlisted men had come from college campuses. Unfortunately, we would gain a reputation as dilettantes since our training included skiing and hiking through the woods. There were movies made about us as well as a lot of newspaper and magazine coverage, which added to our image as a glamorous outfit; some people resentfully called us “Eisenhower’s playboys.” If our critics had known how tough our training was, they would’ve changed their tune.

Some of our training took place on the mountain slopes that would, after the war, become the resorts of Ski Cooper and Vail in Colorado. At Cooper, about five miles south of Camp Hale, we traveled up to an elevation of 10,000 feet using a T-bar lift and then skied downhill with 90-pound rucksacks on our backs. If a man fell, someone had to help him up. It was a completely different technique than skiing without carrying all that weight.

Along with skiing and cold weather acclimation, we had to learn another skill, “mule skinning.” We learned about the care, feeding, loading, unloading, and cajoling of these most stubborn of animals. My mule was named Elmer. We would have to rely on these animals in the trackless mountains where motor vehicles could not go. In any event, we didn’t have motor vehicles except for a few jeeps and tracked vehicles called Weasels.

Finally, we learned rock climbing and rappelling. We didn’t have the advanced equipment of today’s climbers, but we had the basics: carabiners, pitons, small piton hammers, and nylon rope. One of our instructors was Glen Dawson, a prewar climber who had scaled many peaks around the world, sometimes with his friend, the photographer Ansel Adams. Another 10th man, Paul Petzoldt, was a world-class climber who was part of the first American team to attempt to conquer K-2 in the Himalayas—the world’s second tallest peak. Another of my fellow climbers was David Brower who, after the war, would head the Sierra Club from 1952 until 1969. He would remain on their board until 2000.

That spring we were rarely allowed to sleep in our barracks. The instructors had us day and night in the field, skiing, hiking, and grazing our mules. For the most part we slept under the stars. This training would prove very useful when we got to Italy.

Although located in a spectacular setting rimmed by mountains, Camp Hale had its drawbacks. It was located in a high mountain valley through which passed a line of the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad. The coal smoke generated by the steam locomotives (not to mention the coal smoke generated by more than 800 chimneys) lingered in the valley, causing some of the men serious respiratory problems. The resulting persistent cough was known as the “Pando hack,” and some men had to leave the outfit because they were too ill to continue.

The D&RGW soon gained a nickname among the men. We called it “Dangerous and Rapidly Growing Worse.” Perhaps because I was from smoggy Los Angeles, the smoke that filled the Camp Hale valley never seemed to bother me.

After basic training at Hale, we were often able to get weekend passes so we could go into Denver, 100 miles away, or, more often, to Glenwood Springs, which then had a population of only 2,200. It also was home to the world’s largest hot springs swimming pool. On one of these weekends my buddy and I hitched a ride with an older couple in an old car. Along the way, it broke down. A passing motorist promised to send help from the next town. So my buddy and I decided to swim in the nearby stream. As we did, the water level rose and trapped us on the other side near the D&RGW rail line.

We decided to hop a freight train for a ride home. I had never done this before, but my friend told me how to hide behind a rock and jump out, run alongside the train, throw my pack onto a gondola car, then grab hold of and climb the iron steps of the next car––all while trying not to fall under the deadly wheels of the train.

When the train stopped for water (it was a steam train), we confessed to the engineer. He was sympathetic and let us ride in the cab with him. We watched the fireman stock coal into the furnace to heat the boiler and were even allowed to pull the lanyard to sound the whistle. I have been in love with steam trains ever since.

At Camp Hale, when we marched or went on long training hikes, my ROTC training paid off. I was promoted to corporal, which meant that I no longer had to do KP. In the field we ate the infamous “C” and “K” rations—the tinned food of mysterious origin. I have to confess that to this day I still enjoy eating Spam.

It wasn’t long before winter came to the Rockies. We were already aware that the 10th was different from other Army units. Now our white winter camouflage gear really set us apart. Curiously, our wool shirts and undergarments were still olive drab. Our collars were fur lined, and our wool mittens had trigger fingers. It seemed we were the guinea pigs to try out different types of winter gear; we constantly got different boots, hats, goggles, coats, skis, and all manner of other types of clothing from the Army to test.

I became the squad leader of a 60mm mortar squad. We carried heavier packs than the infantrymen. One man carried the tube, another the tripod, another the base plate. Other men, including me, carried ammunition, each round weighing three pounds. It was divided up so that each man carried up to 50 pounds of weaponry and another 40 pounds of personal gear. As a result, we wore snowshoes rather than skis. In deep snow this was a blessing, and we often broke trail for the skiers.

In February and March 1944, the entire division moved out with full packs for a month of war games known as “D Series.” How well we did would determine if the Army would finally send us to a combat zone. We carried our full gear or loaded our packs on mules. That included skis, food, and ordnance. We fired live rounds with our mortars, causing some mini-avalanches in the high country.

At night we dug into the snow and covered ourselves with a 6×8 canvas tarp. If we were below the tree line, we cut pine boughs and laid them under our sleeping bags. Sometimes the temperature would reach minus 35 degrees Fahrenheit. We were always cold. Except for being shot at, the conditions were much worse during the D Series than anything we would face in combat. After returning at the end of the exercises on the snowcapped high mountain peaks, our barracks felt like the Hilton.

All the while political tides surrounded our division. Some Army generals wanted us turned into a regular infantry division to fight on one of the growing number of Allied fronts or broken up and the men parceled out as replacements for other hard-hit divisions. Most of the Army considered us pampered college boys sitting out the war while skiing and rock climbing for sport.

Under the Command of General George P. Hays

In the spring of 1944, most of our mules were taken from us and shipped to Burma to support jungle fighters there. Unfortunately, a great number of them died at sea during the long voyage. But the worst blow to our morale occurred in June when we were transferred from Camp Hale to Camp Swift some 40 miles from Austin, Texas.

Hot, dry, or humid by turns, flat and miserable Camp Swift was dreaded by us all. The move allowed us to expand to division strength by adding raw recruits from around the country. As mountaineers we felt invaded by these flatlanders. However, the expansion of the division did allow us to acquire heavy weapons.

Each battalion gained a heavy weapons company consisting of three sections of .30-caliber machine guns and three sections of 81mm mortars. Each section included two squads and their weapons. We were also issued additional pack artillery and had a battalion of tanks assigned to us. Proficiency in using the 81mm mortar earned me a promotion to staff sergeant in charge of a section consisting of two mortar squads. The 81mm mortar was a beast to haul. The tube, tripod, and base all weighed about 46 pounds each, and it took three men to carry these pieces along with all their usual personal gear. Other men carried several of the rounds that weighed seven pounds apiece but seemed to gain weight the longer you carried them.

While at Camp Swift, we endured eight-hour, 25-mile night marches with but one canteen (about a quart) of water each. We slept amid snakes and insects we had never seen before and never wanted to see again. We felt like an ordinary Army division now, and it was pretty discouraging. Then, in November of 1944, we got the shot in the arm we needed.

When Maj. Gen. Lloyd E. Jones, our commanding general, became ill, he was replaced by Maj. Gen. George P. Hays. Hays was a war hero and a real warrior. He had been awarded the Medal of Honor in World War I for bravery under fire. In this war he had fought at Monte Cassino and taken part in the Normandy invasion.

He didn’t know about mountain troops and could not learn about us on the flat plains of Texas, but he inspired us with his words and actions. He also stood up for us. When our division was offered to General Dwight Eisenhower for use in France, Ike wanted us converted into an infantry division. Hays refused. We were now officially a mountain division, the only one in the United States Army, and there would be no more talk about converting us to an ordinary infantry division. We all admired General Hays, and he would lead us into combat when, finally in December, we were ordered to move again, this time to Italy, where the war had not been going well.

Before leaving Camp Swift, we were issued a little “Mountain” tab that we sewed on our uniforms above our crossed bayonet patch. It confirmed the fact that we were now considered elite troops and morale soared.

The 86th Regiment Arrives in Italy

The 86th Regiment was shipped over first. The converted luxury ocean liner SS Argentina was our troopship. We slept in bunks stacked five high in cramped quarters below deck. Zigzagging across the Atlantic to avoid enemy U-boats, it took us 12 days to reach Naples, Italy. I had time for reading and finished The Razor’s Edge by W. Somerset Maugham.

To our great disappointment, most of our winter gear, white uniforms, sleeping bags, and climbing gear languished in an Army depot. We spent the rest of the war without it.

We arrived two days before Christmas 1944. Sunken ships littered the Naples harbor, and portions of the city were demolished. While in Naples some of us were given day passes to leave our cantonment. It made us realize what this war was doing to people. The weather was cold, but children were running around wearing shorts, T-shirts, and sandals while we had overcoats. They scrounged scraps from our mess kits, ran off, and returned for more. I still remember the desperate condition of the people in this war-ravaged country.

The 10th Mountain Division had been called forward because of the difficulty the Allies faced trying to take the hilltop monastery at Monte Cassino during the winter of 1943-1944; it was a bloodbath for both sides. Now the front line lay in the northern Apennine Mountains north of Florence, and Fifth Army wanted us. We were finally about to get into the fight.

Shortly after Christmas, we were transported to the front—some of us by train and others by ship. We were also issued Italian pack mules that replaced the ones we had lost. Those of us traveling by sea to Livorno were the more fortunate. Our trip up the coast on the Tyrrhenian Sea was uneventful. There was no threat of U-boats, so we enjoyed what scenery was available. Livorno is a smaller port than Naples but was full of activity with Allied ships arriving laden with essential supplies for the troops in and around the northern Apennine Mountains. We then traveled to our staging area near the cities of Pisa and Lucca.

Since the end of the war, I have visited Pisa on two occasions and, of course, taken photos of the Leaning Tower, but my first viewing was in January 1945. We were still in our staging area, and I was on my way to the local hangout when I came across the most beautiful sight. The famous Leaning Tower was poised in brilliant moonlight without any tourists to interfere with the picture, which still remains vivid in my mind.

These outstanding surroundings were soon to be corrupted by tragedy. A couple of our men were walking along a local rail line when they stepped on a mine; the Germans had placed these randomly throughout the area. These men became our first casualties, but that was not the end because a chaplain and one of his assistants clambered down to render aid and encountered another lethal device. They also were killed. Naturally, everyone became aware of this incident, and from then on all of us were stepping lightly without leaving the known paths.

Taking Riva Ridge

Our stay in Lucca was shortened by orders to advance to the front. We traveled east to Florence, then up to Pistoia and into the Apennines. Not knowing what to expect, we were filled with anxiety; there was admittedly a fear factor.

Fortunately, we encountered an unusually mild winter, although we found ourselves advancing into snow-covered mountains and with a light but cold snowstorm in progress. I couldn’t help but be reminded of conditions that most of us endured at Camp Hale during D Series.

There were Allied troops in these mountains right across Italy from Livorno to Venice. We were somewhere in the middle and took our place in the line with the 92nd Infantry Division on our left and the division-sized Brazilian Expeditionary Force on our right. The Germans had fortified the mountain peaks in a chain, manning it with 33 divisions; the Allies had been stuck there since the previous autumn. Every time the Allies tried to advance, the Germans, observing from the peaks, halted them with accurate mortar and artillery fire.

Now, after all our training it was time for us to have a go at it and accomplish what we had been trained to do. Mount Belvedere was the highest peak in our sector. On one flank of that mountain was a series of steep peaks called Riva Ridge. The two German-held peaks offered observation and fire support for each other. The German IV Corps assigned the 334th and 94th Divisions to hold these strategic heights.

My outfit, the 86th Regiment, was assigned to scale Riva Ridge at night; we had to take Riva Ridge before the 87th and 85th Regiments could attack Belvedere. Before the assault, our engineers had cleared a path for us through a German minefield (a lousy detail). They also attached pitons and ropes to the steepest sections so we could climb in the dark. There was no preliminary artillery barrage to soften up the enemy, which would, of course, have alerted them to the fact that an attack was coming.

Hopefully, our advance would be in secret as our men ascended Riva Ridge, which rose steeply above the valley floor. This “ridge” was actually a series of adjoining peaks all ranging from 3,100 to 4,800 feet above sea level.

To ensure surprise, the men were not allowed to load their weapons because any accidental firing would give our approach away. Our mortar unit and other artillery stood by to offer fire support. After dark on February 18, 1945, the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 86th moved out from their hiding places and began a quiet, nighttime climb in four columns up the heavily fortified ridge. My battalion, the 3rd, was held in reserve.

The initial contact with the Germans was a complete surprise to them. We caught them sleeping in their foxholes or just making coffee. The surprise didn’t last. The battle went on for 31/2 days as the Germans kept trying to retake their positions while our men held them off. The Germans were using their versatile 88mm guns to great effect.

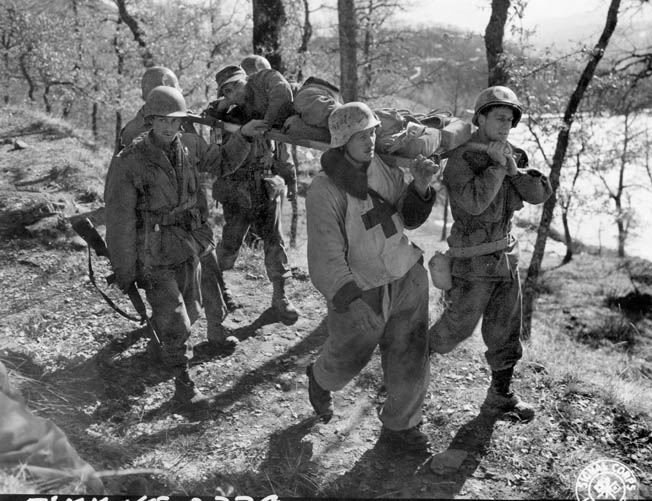

When my 3rd Battalion was sent forward, we found ourselves continually advancing without the opportunity to dig foxholes or set up our mortar pits. There were times when I had some real doubts about any of us getting through these intense battles alive. As it was, we suffered 1,430 casualties on Riva Ridge, but the Germans suffered more.

We had brought with us from the States a makeshift aerial tramway or cable car, which we set up on the ridge to haul up supplies and take wounded men down. Our engineer battalion had practiced setting it up and breaking it down at Camp Hale, and now in combat it worked like a charm.

On the second night, the 87th and 85th Regiments moved out to attack German positions on Mount Belvedere. This time, however, the Germans were not caught napping. Despite our mortar, artillery, and air support, the 87th took heavy casualties, but it also took Mount Belvedere.

Our successes sent shockwaves through the Allied higher command. Allied troops had been trying for months to force their way up these two heights, and we did it within a week. General Mark Clark, commander of the Fifteenth Army Group in the Mediterranean Theater, sent us his congratulations. German prisoners would later say how surprised they were to see our men rapidly moving up the slopes where other American troops walked.

Clash on Mount Della Torraccia

With our success at Riva Ridge came new assignments. My battalion was tasked with taking Mount Della Torraccia, which formed part of the long ridge adjacent to Mount Belvedere. Our efforts were fiercely contested by two veteran German divisions.

I had a particular scare on that occasion. My mortar section was hiking to a forward position when we came under fire from German artillery. My buddy Aarre, a Finnish immigrant (we had a lot of foreign-born soldiers in the 10th), was carrying about 110 pounds of ammunition and gear when suddenly a German mortar round fell between us. Somehow it didn’t explode, but it did cause Aarre to lose his footing. As he fell, his shoulder hit the mortar round. Fortunately, it still didn’t explode, but it left us both plenty scared.

On another occasion our column was advancing through a deep draw in the snow. Shells from a German 88 advanced up the draw to zero in on our position. One shell landed about eight feet from Aarre and me. We dropped to our knees, but luckily that shell, too, was a dud.

Our unit reached the top of Della Torraccia after heavy fighting and had to hold it for several days. We were exhausted, hungry, and thirsty, but still had to ward off continual counterattacks. Once we arrived at our assigned destinations, we instinctively dug in. First, we dug our personal foxholes and then pits for our mortars.

That night we endured a pounding from German artillery before the assault we knew was coming. When the German attack began, they found that we had more firepower than they anticipated. My mortar section and the artillery called in from below overwhelmed their first attack, and they withdrew. There was then a lull when food in the form of ready-to-eat K rations (cook fires would give away our position), water, and ammunition could be brought to us before the Germans reorganized and again tried to throw us back.

During one fierce firefight, we ran out of mortar rounds and could not be resupplied while under attack. Our commanding officer decided we were to become infantrymen despite the fact that I only carried a .30-caliber carbine and my men only had .45-caliber pistols. Fortunately, our infantrymen and other artillery and mortar squads, still supplied with rounds, were able to hold off the attack without our help.

In one night attack, two companies of Germans silently outflanked our position. However, a carefully placed tripwire set off a flare that illuminated their location. Our machine guns and mortars laid into them. After suffering many dead and wounded, 60 of the Germans surrendered while the others retreated in haste.

The counterattacks continued for several days. During lulls in the fighting, we were resupplied, dug our foxholes deeper, and received replacements. The new men had not been trained in mountain fighting, but they soon earned their Combat Infantryman’s Badges (CIB).

It was during this time that I learned the value of that multipurpose tool, the helmet. Although heavy, it could serve to catch rainwater for drinking and washing, or as a pillow. When fires were allowed, some of the guys used their helmets to boil soup or tea. The results were not too appetizing.

Occasionally we would come across small mountain villages in ruins. The locals who had stayed and endured the German occupation rejoiced when they saw us. They shared with us some of the food they had hidden from the Germans––mostly chickens, eggs, and wine. In return we provided them with fruit, canned goods, sweets, and smokes. Occasionally we could even find a roof over our heads at night.

While more Germans were surrendering, many kept fighting, especially with artillery. The Germans had a 150mm artillery piece for infantry support. Called the Schweres Infanterie Geschütz 33, it was accurate to 5,000 yards. When the shells came in, they sounded like a freight train and exploded with an awful sound. If we were on the march with our 100 pounds of gear, we didn’t even duck. We just kept on moving.

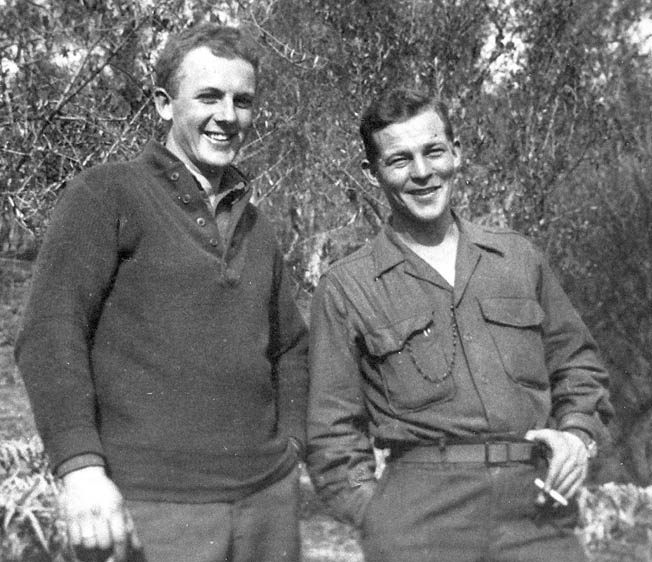

After weeks of fighting, we were relieved. Finally, we could sleep off the ground on cots, shower, and enjoy a hot meal. We were issued clean shorts and brushed our teeth after a long absence from dental hygiene. Best of all, we were offered three-day passes to Florence. Aarre and I jumped at the chance to see one of Italy’s most famous and beautiful cities.

While there, we came upon the opera house, and as a performance was scheduled we were able to buy two tickets when there was a cancellation. The theater was ornate and beautiful. The performance that night was Rossini’s The Barber of Seville, and though we couldn’t understand the Italian words, the music was unforgettable. Aarre and I talked about that night by phone and later e-mail for decades.

The U.S. Army’s Last Cavalry Charge

When we returned to the line after our three-day passes, we set to work with more “soil engineering”—meaning we dug deeper and bigger foxholes. Once we came upon some abandoned weapons from one of our chemical battalions, including a 4.2-inch smoke mortar and machine guns. We happily turned these on the enemy. I especially enjoyed firing the .50-caliber machine gun. It was great fun until the Germans started shooting back.

Around this time, April 12, we learned that President Franklin Roosevelt had died. It saddened our day, but there was little time for mourning. The enemy wasn’t about to let us pause. We were making slow but bloody progress in clearing the northern Apennine Mountains.

A new, massive offensive code-named Operation Craftsman was scheduled for April 14. It was designed to break out of the mountains and drive down into the Po River Valley. It was during this offensive that our recon troop staged the U.S. Army’s last horse-mounted cavalry charge. It did not go well, and many men and horses were killed and wounded when they ran into German mortars and machine guns.

Earlier, the 85th Regiment had received a replacement officer, a young lieutenant who was assigned to be a platoon leader. Although he had not trained with the division at Camp Hale and felt a little intimidated by the elite troops he now commanded, he would have an illustrious career after the war. His name was Bob Dole (no relation to Minnie Dole). He received a crippling wound at Castel d’Aiano on April 14 while attacking a German machine-gun nest (he lost the use of an arm—and almost his life), but that did not stop him from later becoming a U.S. senator from Kansas and being the GOP candidate for president in 1996.

Another casualty on April 14 was Staff Sergeant Torger Tokle, a Norwegian and holder of the world’s record in the ski jump before the war. He was standing next to another soldier who was carrying mortar rounds. Somehow they detonated and both men were instantly killed. Tokle was beloved by his men, and his death was a great blow to the entire division.

Nineteen-year-old Pfc. John Magrath from Connecticut, a member of G Company, 85th Mountain Infantry Regiment, became the 10th’s only Medal of Honor recipient on April 14. Shortly after his company had crossed the line of departure, it came under intense enemy fire and the company commander was killed. Volunteering to accompany the acting commander with a small reconnaissance party moving against Hill 909, radioman Magrath set out with the group. After going only a few yards, the party was pinned down by heavy artillery, mortar, and small-arms fire near Castel d’Aiano.

Instead of flopping to the ground as the others had done, Magrath, armed only with his M-1 Garand rifle, charged ahead and disappeared around the corner of a house, where he came face to face with two Germans manning a machine gun. Magrath killed one and forced the other to surrender. Discarding his rifle in favor of the deadlier German MG-34 machine gun, Magrath killed five more of the enemy as they emerged from their foxholes.

Carrying this enemy weapon across an open field through heavy fire, he wiped out two more machine-gun nests, then circled behind four other Germans, killing them with a burst as they were firing on his company. Spotting another dangerous enemy position to his right, he exchanged fire with the Germans until he had killed two and wounded three. His actions allowed his company to advance and take their objective. Sadly, Magrath was killed later that day when two mortar rounds exploded at his feet.

On April 18, we came up against the 200th Regiment of the 90th Grenadier Division. This elite German unit had fought hard through the entire length of Italy and refused to surrender. It had to be dug out of an already ruined Italian village.

Advance Into the Po Valley

On April 20, Hitler’s birthday, the 10th Mountain became the first Allied unit to leave the Apennines and descend into the Po Valley, the breadbasket of Italy. The mountains that we had taken from the enemy had guarded the valley and kept it in German hands—but no more.

We were the spearhead of the Fifth Army thrust in the western half of Italy while the British Eighth Army was to our east. There was also the Brazilian Expeditionary Force and groups like the Nisei 442nd Regimental Combat Team (which had fought in Italy earlier, had taken part in the invasion of southern France, and then returned to Italy to fight again) in the line as well.

Around this time I acquired a Thompson submachine gun and two extra clips of ammo when one of my gunners traded his .45-caliber sidearm for it with a tank crewman. When he got tired of carrying it, I swapped him for my carbine. Despite the added weight, I enjoyed the feeling of having extra firepower.

We were now supported by tanks, and this made life easier, except on occasions when one of our own planes mistook our advancing Shermans for retreating German panzers. They would shoot up our boys pretty badly before we could set out the yellow smoke signal that identified us as friendlies.

When it was time for the big push down into the Po Valley floor, our friends with the British Eighth Army prepared for their push with a tremendous artillery barrage. Even though we were miles away, their cannon fire sounded like a continuous roll of thunder along with the flashes of explosions and tracer rounds. This show lasted nearly an hour, and then it was our turn.

Our initial advance was just a short distance, and we halted in the darkness, not even taking time to dig foxholes. We ignored security for some much-needed sleep. Meanwhile, our engineers went forward rebuilding roads and trails and placing tape to guide us safely through minefields.

When we finally reached the valley floor, we rushed forward as fast as we could to keep the Germans from reorganizing and hopefully to cut them off from escape into the Alps. We crossed the Po River at the town of San Benedetto Po. The Germans had blown all the bridges in the area, so we were forced to cross in small boats with the use of paddles while under fire.

During our advance against retreating German troops across the Po Valley, we walked for two days and rode for one (what a treat!). However, we would occasionally encounter resistance in the form of sniper fire, which was usually dealt with by tanks or our air support. When a P-47 Thunderbolt dropped a 500-pound bomb on a building housing a sniper, it was all over for him.

Late one afternoon when we were riding on trucks, a Luftwaffe plane dove down and strafed our column. We all jumped out of our vehicles and scattered. I ended up beneath our truck. It was then that I realized that in the last town we had driven through the locals handed us food, vino, and even eggs. I had placed one egg in each of my pockets, but they don’t hold up well when you are diving for cover. One egg did survive, but to prevent a recurrence I immediately downed it whole. I normally prefer them poached, but what the hell.

One of the most rousing welcomes we received was in the city of Verona, known to us previously only through Shakespeare. Verona is at the base of the Dolomite Mountains, the Alps of northern Italy. Our battalion commander had been ordered to hold up so the rest of our regiment could catch up. But he was hell bent to lay claim to the celebration. It was just like in the movies with us riding through the broad streets and plazas with the entire civilian population greeting us. Their gratitude was overwhelming, making us feel proud that we had played a real part in bringing peace and freedom back into their lives.

This was a happy moment during a time when I couldn’t help but think about all those killed in action. Their bodies, mostly German, were strewn across the battlefield and the roads we traveled. It makes me wonder just how hardened we had become while so close to a similar fate.

Fighting at Lake Garda

In the third week of April, our line of march led us to the shores of Lake Garda, Italy’s largest lake, and the worst casualties we would suffer. The lake was 32 miles long, but the western shore consisted of sheer cliffs that plunged almost straight down into the water. We had to cross to the eastern shore, where progress could be made through six tunnels that had been constructed before the war.

The enemy had fortified two towns at the northern end of the lake, Riva and Torbole. From these strongholds they rained shells down on us. Only one man was lost in the crossing, but he was a buddy of mine who was killed by a shrapnel splinter through the helmet.

On the eastern shore we advanced northward toward the series of tunnels that accommodated the road just as the Germans blew them up. One group of German engineers accidentally blew themselves up just outside the entrance to one of the tunnels. Fifteen men were killed along with some of their horses.

While our engineers worked to clear the tunnels, we looked for ways around them. General Hays ordered up some amphibious vehicles named DUKWs, but universally known as “ducks.” The DUKWs came forward and carried elements of the division across the lake to avoid the blocked tunnels.

The DUKWs were loaded to the gunnels but off they went. They came under fire from German positions but made it safely to the shore. Later that day another DUKW loaded with artillerymen was swamped, drowning 24 men. There was only one survivor. (See WWII Quarterly, Summer 2013)

At the last tunnel, I was ordered to take my mortar team to the top of a ridge and fire a suppressive barrage toward the town of Torbole, from which the Germans were still firing at us. When they found out where we were, they fired back at us with 20mm cannon. One of these guns was housed in a three-story building with Red Cross markings. Since they abused their neutrality, we zeroed in on the building until their shooting stopped.

When we ran out of ammunition, we scrambled back down the slope only to find that we had been extremely fortunate. Inside the tunnel our men were advancing to the northern entrance. The Germans, meanwhile, got lucky and landed an 88mm shell inside the entrance, killing five of our men and wounding 50. One of the wounded was my friend, Ray Hellman, of the mayonnaise family. He always wore a St. Christopher’s medal around his neck. That day a fragment struck him in the chest but hit and mangled the medal, saving his life.

The 10th Mountain Division After the War

By the end of April, we had reached and taken Torbole and were preparing to move northward. On April 30, one of our highest ranking officers was killed. He was Colonel William Darby who, earlier in the war, had founded and led the Army Rangers and won the Distinguished Service Cross. Now he was our assistant division commander. Stepping out of his headquarters and mounting a jeep for a ride to the front, he was killed by a random 88mm artillery shell fired by the distant enemy. He was our last casualty.

On May 1, we moved on to the town of Riva, where we heard rumors that the Germans were ready to surrender. All shooting stopped, and for us the war was over. Yet, we were almost involved in a new war.

In Yugoslavia, communist partisans under Marshal Tito had taken over the country. Fearing the Yugoslavs might have territorial claims on Italy, our entire division, along with elements of the British Eighth Army, was ordered to the border between the two countries near the city of Trieste. We arrived on May 20 and remained there until the situation stabilized. On July 14 we were ordered home.

I sailed home with the rest of the 86th Regiment on the SS Westbrook Victory to begin training for the invasion of Japan. While still steaming across the Atlantic Ocean, we learned about the atomic bombs and their terrible effect. Japan surrendered shortly after our arrival at Newport News, Virginia.

By the end of November 1945, the 10th Mountain Division was deactivated. But that is not the end of its service to America. In the postwar era, as many as 62 ski resorts in the United States were founded or run by veterans of the 10th. At Vail, Colorado (founded by 10th veterans near Camp Hale), a ski slope is named Riva Ridge in their honor; another is called “Minnie’s Mile,” to pay tribute to the man whose tireless efforts had led to the creation of the 10th. In 1985, the division was reconstituted, and as the 10th Light Division it has been deployed to such places as Haiti, Somalia, Bosnia, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

As I look back on my service with the 10th, I have feelings of great pride mixed with sadness in remembering the 1,000 young men who gave their lives to put an end to the Nazi menace.

This story was published in WWII Quarterly magazine.

Thanks

My father was in the 87th Mt. Infantry Regiment (10th Mt. Div.) and fought in Italy during WW2. He also was from Southern California. Being his son, I am very familiar with the history of the 10th M.D. fighting in Italy. However, I always find it very interesting and educational to read another 10th veterans personal memories of training and the war. It always broadens the picture I have of my fathers experience during the war. Thank you for posting this memory.

Thank you for the story. My Grandfather, Gordon Q. Jones who passed away in 2017 and served in WW2 had a cousin who served in the 10th Mountain Division. His name was John Paul Jones. He was killed in action Feb 20th, 1945 in Italy. There is a famous ski run named after him at the Snow Basin Ski Resort in Utah. It’s simply known as “John Paul.”