By Pedro Garcia

Not long after Union Flag Officer David Farragut of the West Gulf Blockading Squadron received the surrender of New Orleans on April 29, 1862, he began pondering his next move. He faced a dilemma. His orders, as framed by Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, did not resolve the question. Should Farragut attack Mobile, Alabama, his secondary objective, or press up the Mississippi River, clearing out the secessionists and ultimately joining forces with the ironclad gunboats of the Western Gunboat Flotilla under Flag Officer Charles H. Davis? Farragut’s blue-water navy was not suited for brown-water work, and he would have much preferred to leave it to Davis. But control of the river was a priority of the Lincoln administration as a means of splitting the Confederacy economically, militarily, and politically. Union control of the Mississippi would sever Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas from the rest of the Confederate states.

Farragut resolved the dilemma by splitting his forces, sending his mortar flotilla to the barrier islands off Mobile Bay while also sending several small gunboats upriver to Vicksburg. As Farragut’s gunboats proceeded upstream, receiving the surrender of Baton Rouge and Natchez, Davis’s hard-driving Federal ironclads had captured New Madrid, Island No. 10, and Fort Pillow and were working their way downstream toward Memphis.

On May 18, Farragut’s fleet arrived before the bluffs of Vicksburg. However, the guns of Farragut’s ships had trouble hitting Vicksburg’s forts, and his difficulties were compounded because the infantry force accompanying him was woefully inadequate to attack the city. Frustrated by his inability to force the issue, Farragut returned to New Orleans. Meanwhile, on June 6, the Western Gunboat Flotilla destroyed a Confederate fleet and forced the surrender of Memphis. The capture of Memphis culminated five months of impressive operations by Davis’s flotilla, which had begun in February with the combined assaults on Fort Henry and Fort Donelson. Those operations broke open the war in the West and allowed the Union military to use the Tennessee and Mississippi Rivers as highways penetrating deep into the Southern heartland. Now the whole Mississippi looked open to the Union Navy.

By June 18, the newly promoted Admiral Farragut was back before the bluffs of Vicksburg. He was joined by a nominally larger infantry force, and within two weeks the Western Gunboat Flotilla had arrived from Memphis, putting the crucial fortress in a vise-like grip. Even so, taking Vicksburg would not be easy. Defended by 10,000 Confederates, it was clearly impossible to carry the city by assault with the force at hand. More troops were not forthcoming. Other problems beset Farragut in mid-July. The river was falling, threatening to strand his ocean-going warships, and malaria devastated the Union infantry. To add to his woes, the Confederate ironclad Arkansas brazenly ran the gauntlet of the two Union squadrons anchored above Vicksburg. His patience at an end, the frustrated Farragut was again compelled to abandon his effort to take the fortress.

The Fortified Port Husdon

The successful defense of Vicksburg and the recovery of the upper reaches of the Mississippi between Port Hudson and the city invigorated Confederate authorities to renew their efforts to secure their base at Vicksburg and keep open the free flow of commerce via the Red River from the Trans-Mississippi West to the armies in the East. Efforts took on an air of urgency in August, when the Confederates failed to retake Baton Rouge and lost the ironclad Arkansas. However, the Battle at Baton Rouge turned out to be a strategic triumph for the Confederates when the exposed Unionists evacuated the city 10 days later, withdrawing to New Orleans and yielding another 50 miles of the great river to the Confederacy. Clearly, the Union grip on the river had loosened, and southerners still held the key to the lower Mississippi Valley.

The most feasible and logical position to anchor the Confederate line was on the 80-foot bluffs at the small Louisiana town of Port Hudson, situated on a 150-degree bend of the Mississippi River. The negotiation of the bend was slow and tedious work for any ship traveling up or down river. There the Rebels built a high-bastioned fortress in almost the exact configuration of Vicksburg. Located 25 miles north of Baton Rouge, 150 miles upriver from New Orleans, and 110 miles downriver from Vicksburg, a series of tiered and fortified batteries covered the river approach below the town and enfiladed the sharp, shoaling left turn immediately above. The 21 heavy guns placed there could methodically rake passing ships with concentrated and blistering fire.

On the landward side, the Confederate position at Port Hudson extended some 4½ miles in the form of a semicircle, with its lines bowing eastward. The numerous ravines and gorges that traversed the area dictated a defense on strongpoints, with high ground well posted by 22 field pieces. By the end of 1862, Port Hudson boasted over 9,000 Confederate soldiers. If the Federal high command did not do something quickly, Port Hudson would become another Vicksburg. Indeed, until the Rebels could be ousted from these two strongholds, the work of clearing the Mississippi remained only half accomplished.

“I Must Go- Army or No Army- or be Sunk in the Attempt”

The new year opened on a sour note for Farragut. The Confederates were able to puncture the blockade of his Gulf Squadron in Galveston Bay and Sabine Pass, Texas, as well as at Mobile Bay. While Farragut was champing at the bit to run the batteries at Port Hudson, his pugnacious tendencies were tempered by the need to shore up the blockade in the Gulf. Still reeling from these damaging body blows, the tenor of the strategic picture worsened in late February with the loss of the Union rams Queen of the West and Indianola. Their capture meant that the Confederates had definitely regained control of the waters between Port Hudson and Vicksburg. Jarred out of its lethargy, the Union high command struggled to regain the initiative.

Farragut determined to run the frowning batteries at Port Hudson. He asked Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks, commander of the 20,000-man Department of the Gulf, to make a diversionary demonstration while he ran the gauntlet. Banks procrastinated, conducted a reconnaissance, and ultimately did nothing. The ever-impetuous admiral remained undaunted, explaining to his chief of staff: “If we can get a few vessels above Port Hudson, the thing will not be an entire failure, and I’m confident it can be done. The time has come, there can be no delay. I must go—army or no army—or be sunk in the attempt.”

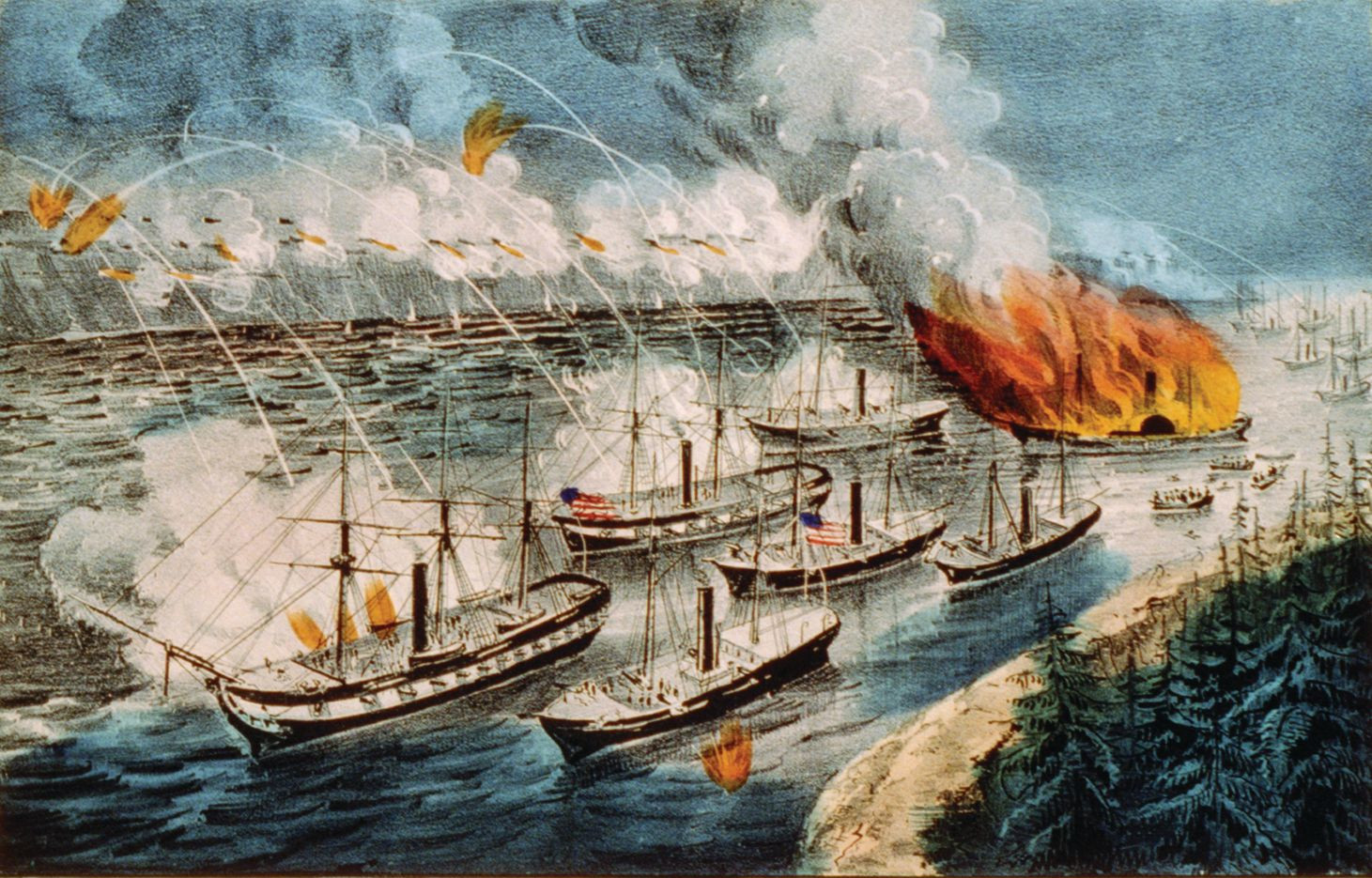

High noon arrived at 10 pm on March 14, when the assembled vessels weighed anchor at Profit Island, five miles below Port Hudson. Farragut’s 3½-mile run would be made by three heavy sloops-of-war, Hartford, Richmond, and Monongahela. They would be followed by the side-wheeler Mississippi, an ironclad, five gunboats, and six mortar schooners bringing up the rear. As each vessel negotiated the 150-degree bend in the river and passed the batteries, it would have to execute a sharp turn to port against a strong current, exposing its stern to a raking fire.

To facilitate this movement, Farragut came up with a novel approach. He ordered a gunboat lashed to the disengaged side of each of the big ships—the five-gun Albatross to the 24-gun Hartford, the nine-gun Genesee to the 24-gun Richmond, and the two-gun Kineo to the eight-gun Monongahela. The arrangement could not be done with the 17-gun Mississippi because of her massive paddle boxes. The major advantage to this ship-coupling was that if the large warship became grounded or disabled in any way, the gunboat would be able to assist. It gave the ships the maneuverability of a twin-screw steamer, and at the same time protected the gunboats with the thicker sides of their consorts.

Although the gunboats were lashed to the sides of the sloops, they would be far enough aft to allow broadside guns clear access. Farragut also ordered a voice trumpet to be run from Hartford’s wheel to her mizzen-top so that the pilot could give commands from above the smoke and din of battle.

The Hartford and the Albatross Run the Gauntlet

At 11:20 pm, Hartford appeared below Port Hudson’s batteries. To avoid obstacles on the west side of the river, the flagship passed so close to the Confederate-held east bank that her rigging brushed against the trees.

Ten minutes later lookouts split the darkness with a signal rocket, and huge bonfires flared on the opposite shore, their flames magnified in reflectors placed behind the trees for better illumination. They also switched on a series of locomotive headlights and a calcium-powered searchlight, sending shafts of blinding light onto the river. Thus illuminated and silhouetted as if on stage, the flotilla received, accompanied by the bone-chilling Rebel yell, a perfect storm of shot and shell. Lieutenant George Dewey, future hero of the Battle of Manila Bay, remembered, “The whole crest of the bluff broke into flashes.” The mortar schooners answered as best they could, and the flagship unleashed a broadside that was taken up in turn by the ships astern.

For the next 90 minutes the stretch of the Mississippi fronting the Rebel bastion was a seething arena of screaming missiles punctuated by unholy explosions. Furthermore, the smoke from engines and guns hung over the river like a sulfurous blanket in the still and heavy air, leaving helmsmen groping blindly and gunners with nothing to aim at but overhead muzzle flashes. Frequently, Hartford and Albatross had to cease firing so the pilot could con the ships. Even so, he all but missed the left turn just above town at Thomas Point (a shoal that jutted from the inner elbow of the turn), and the current swung the flagship’s bow toward the east bank. For a few suspenseful minutes Hartford kissed the mud, her head toward the enemy. Farragut lifted a hailing trumpet to order: “Back! Back on the Albatross!”

The gunboat threw her screw in reverse and eventually freed Hartford. However, Confederate gunnery was accurate and the flagship was much damaged about her tops and spars. Loyall Farragut, the admiral’s son and unofficial orderly, faltered momentarily as a barrage of shots tore up the decks. “Don’t duck, my son, there is no use in trying to dodge God Almighty.” It was good fatherly advice. At 12:15 am the flagship and her escort were safely above the Rebel batteries, relatively unscathed, with the loss of only one man. The rest of the fleet would not be so lucky.

Sealing Vicksburg’s Fate

Frustrated at the safe passage of the flagship, Confederate gunners fired with trip-hammer rapidity. Richmond and her escort Genessee were hammered relentlessly. Lt. Cmdr. A.B. Cummings, who lost a leg during the run, declared, “I would rather lose the other leg than go back.” However, Richmond, too, might have succeeded in getting above the batteries were it not for a shell that slammed into the engine room, knocking off the steam safety valves. The propulsion spaces and berth decks filled with super-heated, scalding steam and pressure dropped. To make matters worse, a mine exploded under her stern, shaking the ship like a leaf, blowing out windows and wrecking a heavy gun. Four firemen later received the Medal of Honor for their work putting out fires in the damaged starboard boiler. Nevertheless, against a five-knot current, Genessee was too weak for the both of them to fight, and the current swung them around to head back downriver. Some of the crew, who were unaware they had swung around, accidentally fired on Mississippi, mistaking flashes off the port for the enemy.

The third ship in line, Monongahela, was subjected to withering sharpshooter fire from the west bank. Her escort, Kineo, took a shot in her rudder post, and her propeller fouled. Meanwhile, Monangahela, having to steer for both vessels, was caught in an eddy and lurched aground. Swept by the momentum of the current, Kineo tore free from her lashings and drifted rudderless out of the fight. About midnight, Monangahela freed herself from the bottom, but not before the bridge was shot from under her commander, severely bruising him and killing three others. Her executive officer assumed command, but a crank pin overheated and her engines froze. She too drifted helplessly out of the fight.

An even worse fate awaited Mississippi. Running alone, the old side-wheeler, which had served as Commodore Matthew Perry’s flagship during the Mexican War and his first expedition to Japan, was breasting the current at a brisk clip when her pilot became disoriented as she approached Thomas Point. The vessel ran hard aground and heeled over to port. The paddle wheels were reversed at full power, and portside guns were run in to get her on even keel. For 45 minutes Mississippi’s engines struggled mightily at nearly double steam pressure to free her from the shelving bottom, but the ship did not budge an inch. Meanwhile, Confederate shore batteries raked her mercilessly, and red-hot shot from the guns set her on fire. In a few minutes, Mississippi was ablaze in four different places between decks. She would be abandoned in flames and scuttled to prevent her falling into Rebel hands.

In the run past New Orleans, only two Union vessels had failed to make it. The butcher’s bill for running the gauntlet at Port Hudson was much higher. Although Hartford had only been hulled four times, Richmond and Monongahela had been severely handled and Mississippi had been lost. The fleet lost 35 dead and 77 wounded compared to only eight Confederate casualties. Against this bleak tableau, Farragut nevertheless had done what he set out to do. His passage sealed the doom of Port Hudson and Vicksburg, for both garrisons were dependent upon the resources of the Trans-Mississippi for existence. The presence of Hartford and Albatross at the mouth of the Red River ensured that cattle and grain west of the river, along with any goods that might be smuggled in through Mexico from Europe, were now inaccessible.

Port Hudson Besieged

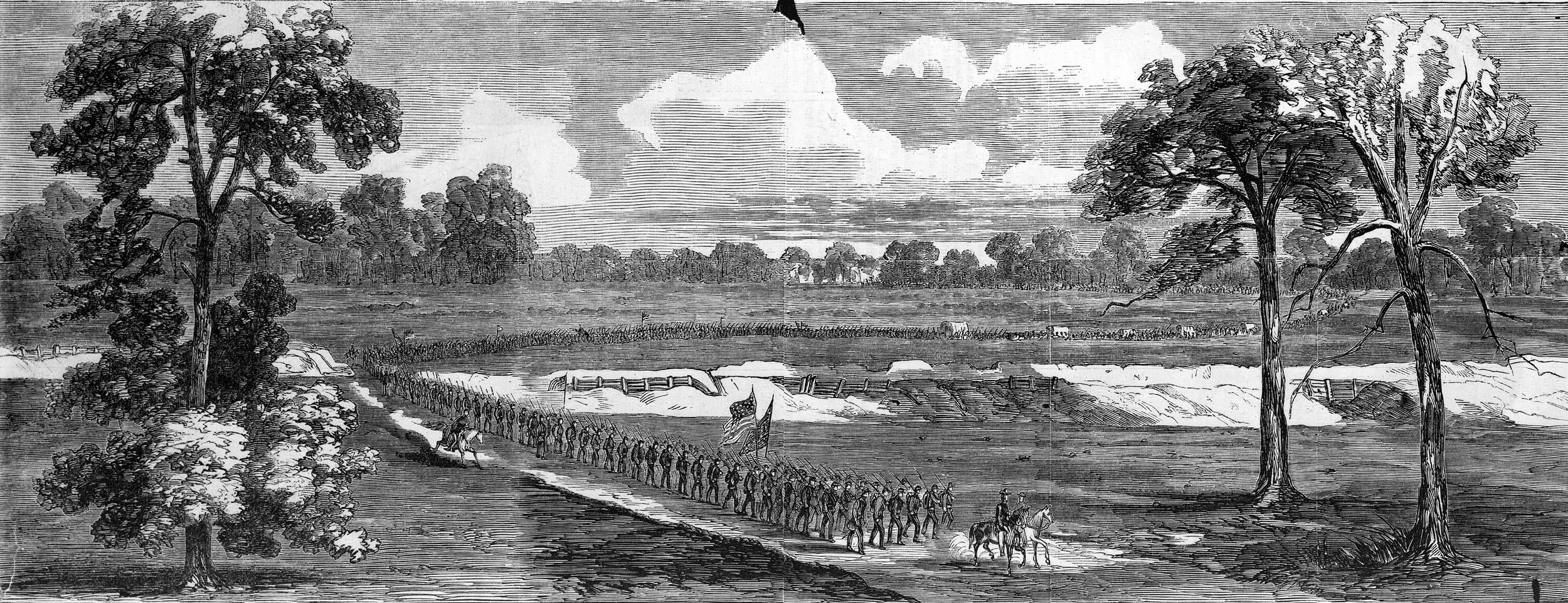

As commander of the Department of the Gulf, Banks’s primary duty was opening the Mississippi to Federal commerce throughout its length. This meant cooperation with Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, who was engaged in loosening the upper hinge of the river at Vicksburg. Banks was expected to make his way upriver from New Orleans to effect a juncture with Grant at Vicksburg. The major obstacle confronting him was Port Hudson, and by early April he had decided to turn it. Moving up Bayou Teche to Alexandria in central Louisiana, Banks marched his army down the Red River to its confluence with the Mississippi. By May 22, his army was across the Mississippi and investing Port Hudson from the north, while Federal troops from Baton Rouge sealed off the fortress from the south.

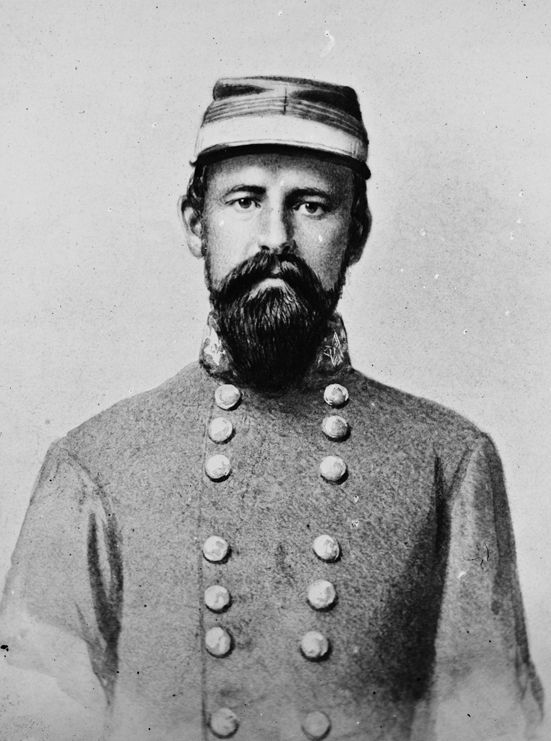

A cordon of blue steel encircled Port Hudson for nearly six miles from one bank of the Mississippi to the other. The Army of the Gulf boasted 20,000 men, and they crowned their superiority with 90 pieces of artillery. The Union navy completed the investment of the fortress, as over a dozen gunboats and mortar boats roamed the river and maintained a regular and continuous bombardment. On May 26, Banks sent a formal request for surrender to Port Hudson’s New York-born commander, Maj. Gen. Franklin Gardner. The request was flatly refused. Gardner’s strength had risen to 15,000 men in early April. However, because of levies by the department commander, General Joseph Johnston, reacting to pressure from Grant, Gardner had seen that figure dwindle to less than 6,000 effectives. His ranks had been so thinned that at some points in the line the men were posted five feet apart. Augmenting the 22 pieces of field artillery, many of the heavy riverfront guns were mounted on pivot cartridges that could be swung around against land forces in the rear.

Gardner had deployed his lines with care, anchoring both extremities to the lip of the 80-foot bluffs overlooking the river. The two main forts, the Citadel and the Priest Cap, with a small redoubt between them, were tied together by a network of trenches. These fortifications, parapets, ditches, and gun emplacements were mutually supporting—an advance on one position invited fire from those adjoining it.

“A Gigantic Bush-Wack”

A furious cannonade by Federal artillery broke the first grayness of daylight on May 27, and soon the mortar schooners in the river joined in with thunderous high-angle fire. Confederate guns responded in kind, but it was an unequal contest and many were wrecked. When the preliminary bombardment died down at 7:30 am, Union infantry stepped briskly out from the shadows of the dense magnolia forest into the daylight. The advance was made by two brigades on the right, commanded by Brig. Gen. Godfrey Weitzel. Some 600 yards to his left and slightly to the rear, Brig. Gen. Halbert Paine sent one brigade forward.

Banks had planned the infantry assault to be synchronized, but the plan soon devolved into a series of badly coordinated and disjointed piecemeal attacks. Pressing forward at a run in broken terrain laced with fallen timber, the bluecoats sent enemy skirmishers tumbling back into their works. Meanwhile, a Confederate battery on Commissary Hill erupted with murderous effect at point-blank range. Men were swept off their feet, and gaping holes appeared in the once-ordered lines. The advance slowed to a snail’s pace as the Federals hugged the ground or sought whatever cover was close at hand. Southern commanders could be heard barking out orders, “Take good aim, boys, and break their legs.” Still the Federals came on, crawling and darting forward through a maze of obstructions and embankments.

Eventually, Weitzel’s troops reached and held a ridge some 200 yards away from the Rebel line. Five batteries were brought up in support of at least three different charges by individual units, and the fight was close and desperate. But such close-quarter fighting cannot be sustained without substantial and orchestrated support, and the Federals recoiled with horrid losses. To the left, Paine made surprising progress in closing with and getting the better of the defenders, but after support failed to materialize his troops were compelled to give up the hard-won real estate. A participant ventured the opinion that what he had been involved in was not so much a battle as “a gigantic bush-whack.” Although skirmishing and sharpshooting continued, the fight became a deadly stalemate. Weitzel now looked to the extreme right to shake things up.

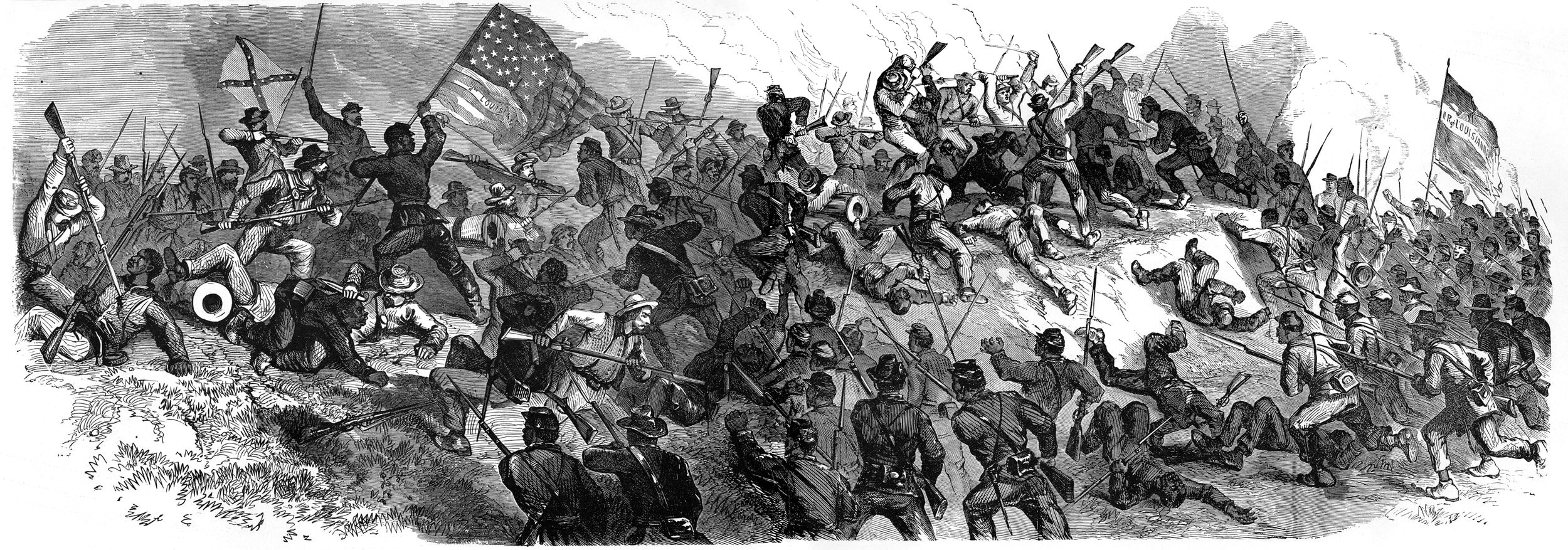

A First Clash For Black Troops

The 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guards occupied a position about half a mile away from the Confederate line, straddling the Telegraph Road that ran along the Mississippi River between Port Hudson and Bayou Sara. The Native Guards were African American troops, mostly free blacks from a New Orleans militia unit. Their commander, Brig. Gen. William Dwight, sought to create a diversion for Weitzel by sending both regiments on a move against the extreme left of the enemy, where the line bent back southward toward the river. Unfortunately, he knew nothing of the ground over which his troops would operate, nor had he consulted a map. Dwight, a notorious misfit, prepared for the attack by getting drunk and indifferently dispatching the Native Guards to storm an impregnable hilltop position. In fact, it was about the strongest position at Port Hudson. There were 60 soldiers in rifle pits on a elevated outwork to their left, 300 soldiers and six cannons on the bluff to their front, and two heavy guns in a water battery to the south.

About 10 am, the Native Guards, over 1,000 strong, formed lines in a grove of willow trees just south of the Telegraph Road. Two cannons were brought up and challenged the six Rebel guns. So effective and precise was the counterfire that the northerners got off only one round before they hastily withdrew, losing two men and three horses in the duel. It was discovered that southern gunners had nailed white crosses to trees in order to zero in on opposing batteries.

The Guards emerged from the protection of the willow trees, forming four ranks deep onto the road. Pressing forward at the double-quick, they immediately began taking hits from the sharpshooters in the outwork to the left. At 400 yards, a torrent of shot, shell and canister exploded into the ranks, staggering the line. The Guards held together and swept forward. A white officer recorded: “Valiantly did the heroic descendants of Africa move forward, cool as if marshaled for dress parade.” Surging, the troops came to within 200 yards of the Confederate line.

Rebel riflemen now unleashed a ripping volley at point-blank range, and the water battery to the south added a devastating enfilade fire. The Native Guards managed to get off a single ragged volley, but any cohesion disappeared under the immense firepower. Thoroughly demoralized, the panic-stricken troops broke in confusion and retreated to the grove of willow trees. Officers worked hard to reform ranks, and small detachments of the black troops made two more courageous but futile attempts to come to grips with the enemy. The engagement had the distinction of being the first of any magnitude between black and white troops in the Civil War.

The Federals Repulsed

Dead calm settled over the battlefield. Banks was beside himself with agitation at the disruption of his plans. Finally, Brig. Gen. Thomas Sherman, on the Union left, mobilized his two brigades for an assault on the thinly held rebel right. At 2:15 pm, with parade-like precision, Sherman’s men charged onto an open field and a steady shower of lead and iron. Sherman and two staff members were quickly shot from their horses; one of Sherman’s brigadiers, Neal Dow, was wounded twice. Confederate Colonel William Miles calmly reassured his men, “Shoot low, boys, it takes two men to take away a wounded man, and they never come back.” Three times the Federals advanced, and three times they were hurled back. Officer casualties continued to mount, and soon all command and control were lost.

The battle degenerated into a back alley fight. Driven by desperation and fright, men acted on their own initiative, firing blindly. Isolated companies formed as best they could, charging and recharging, only to recoil with appalling loss. By 4:30 pm, it was all over. As survivors trickled back, attention shifted to the center where Maj. Gen. Christopher Augur’s division had moved at the sound of Sherman’s attack. His men rolled forward, but less than 200 yards into the advance Augur’s troops likewise became mired in the log-choked terrain, and the attack stalled less than 100 yards from the enemy line.

Banks had one card left to play, and that was Brig. Gen. Cuvier Grover. Once again contrary to the designs of the commanding general, Grover had been ordered to coordinate his assault with Augur’s advance, but his troops did not advance until 3 pm, by which time Augur’s effort was fairly spent. In consequence, Grover’s advance was a piecemeal affair. Only two regiments went forward against the ¾-mile-long front west of Port Hudson. For over an hour they toiled in a maze of obstructions to reach their objective, a seemingly impregnable U-shaped fortification known as Fort Desperate. The ensuing fight was indeed desperate. Making excellent use of interior lines, the 293 Confederate defenders repulsed and pinned down the much larger Union force. The few soldiers determined enough to scale the breastworks were greeted by bayonets. Grover sought to create a diversion that would allow his troops to breach the works, sending in two more regiments from another direction, but this, too, proved fruitless—they were pinned down as soon as they started. Fighting ceased by 5:30 pm.

The Starving Confederate Camp

The day had been terribly mismanaged from the Union perspective, and the night brought additional horrors. Medics and orderlies stumbled through the darkness, retrieving the maimed and burying the dead. The mood was dismal and sullen as Banks’s army tallied its losses: 293 killed, 1,545 wounded, and 157 missing. In contrast, the Confederates took only 235 casualties. Poor communications, shoddy cooperation, and a rough terrain that prohibited anything but piecemeal attacks convinced Banks that he must resort to siege tactics to take Port Hudson.

Accordingly, he called up nine additional regiments and brought in huge siege guns to open up a one-sided, long-range artillery duel. Nearly all of the Confederate artillery was silenced, and as the siege wore on the defenders scarcely fired their cannons to save ammunition. Troops and contrabands were set to work digging lines of contravallation and constructing breastworks, or saps as they were called. Tiers of logs were laid; notches were cut in the logs to provide portholes for snipers and observers. These saps were six feet high and 30 to 100 feet long, the length dependent on the number of guns. In some places, the Union works came to within pistol shot distance of the Confederate line.

Life in the trenches was grim. Sunstroke, malaria, and diarrhea played no favorites between the blue and the gray. Sharpshooters on both sides plied their trade with deadly efficiency. As the weary June days wore on, Confederate food stocks dwindled, and the men were put on half rations. One Confederate soldier said later that he and his comrades eventually ate “all the beef, all the mules, all the dogs, and all the rats.”

Failed Assault on June 11

In the fortnight since the late-May investment and assault of Port Hudson, Union confidence had given way to doubt. The wretched failures, incompetent leadership, sickness, fatigue, and ever-present danger of sudden death had worn on the besiegers. The high command itself was riven with bitter personality clashes fueled by bureaucratic turf wars and petty jealousies. An impatient and frustrated Banks decided on a probing night action in the early morning hours of June 11.

The operation was doomed from the start by the ambiguity of the orders and the lack of enthusiasm of the officers charged with is execution. “The futility and foolhardiness of the thing was clear to all, we looked upon our instructions as simple madness,” one Union captain lamented. At 1 am, accompanied by a stepped-up bombardment, the blue infantry crept forward in the misty darkness and found the enemy pickets all too alert. The butternuts sounded the alarm, and the main line poured galling sheets of fire at anything that moved. Some Federals actually made it through the abatis and up to the hostile lines, but those who were not captured were quickly driven back. At 3 am the skies opened in torrents, drenching the struggling Yankees, while flashes of lightning illuminated an endless stream of demoralized soldiers drifting rearward. Confederates taunted them: “What’s keeping you fellas? Come on over. We’re waiting for you.”

Port Hudson’s defenders still held out the hope that General Johnston, who was assembling a force at Jackson, Mississippi, would come to the relief of the besieged garrison. Gardner sent couriers through enemy lines with coded messages advising him of the garrison’s predicament, but it was a forlorn hope. Meanwhile, a quartet of soldiers did desert with claims that the garrison was about played out and staring starvation in the face. To test the validity of the reports, Banks ordered a wickedly intense bombardment on June 13, to be followed by a summons to surrender.

By now the Union fleet was running low on ammunition, and Farragut saw little use in such tactics. “After people have been harassed to a certain extent, they become indifferent to danger, I think,” he complained to Banks. A Federal colonel observed: “The bombardment has lasted an hour and ended. A flag of truce has gone to demand the surrender of the place. We do not have to wait from the flag of truce to know that the people of Port Hudson are not all killed, for along the parapet, both ways from the redoubt, up come the gray-backs out of their holes, like so many prairie dogs.”

A Battle of Attrition

The Federals had done their worst, but the defenders had barely been disturbed. Having emerged relatively unscathed from the most intense artillery barrage the enemy could muster, Gardner tersely refused the demand for surrender. Banks now planned a complex, three-pronged assault in which Grover and Weitzel were to attack Priest Cap, the fortification at the northeastern salient of the Confederate line. In the center, Paine and Augur would move forward along the Jackson Road. On the far left, Dwight was to strike at the largest of the Rebel fortifications, the Citadel, so named because it dominated the ground in that direction.

The qualities that marked the dismal failures of May 27 and June 11 continued to propel the army on its hapless course. Dawn broke in a blood-red hue on June 14, and the ground shook with a vigorous one-hour cannonade, which served little purpose except to warn the Confederates that the Federals were coming. The primary effort at Priest Cap was stopped in mid-career when it was demonstrated that no man could clear the fire-swept ridge along their front and live. A Union officer declared, “In examining the ground afterward, I found one grass-covered knoll shaved bald, every blade cut down to its roots as by a hoe.”

The defenders had laid row upon row of trip-torpedoes made from unexploded shells that could be detonated by pulling on a piano wire attached to friction primers. In the center, Augur and Paine attacked with admirable vigor, and three regiments managed to breach the Rebel line. A desperate hand-to-hand melee ensued. After Paine fell with a shattered thigh, the attack fell apart. On the far left, Dwight’s attack was long overdue—he and his staff had started the day by getting drunk. Consequently, the assault on the Citadel was so poorly planned and badly executed that it could scarcely be called an assault. By sunset, it was apparent that the Union attack had failed in every sector. The price exacted for a few yards of shell-torn earth was staggering. The Yanks had suffered another 1,805 casualties, while the Confederates had lost a mere 47. Demoralization and disillusionment again became rampant among the besiegers. A private soldier captured the mood with searing clarity: “We are poorly led and uselessly slaughtered, and the brains are all within and not before Port Hudson.”

The war of attrition continued, and the work of siege fortifications, or zigzag approaches, was pushed on night and day, focusing on three major points. The primary approach was on Paine’s front, where his attack had come close to breaking through. The trenches ran parallel to, and within 20 yards of, the right face of Priest Cap. A second approach was in Grover’s front, where he faced the enemy line at Fort Desperate. The zigzag approach was built in a relatively direct manner, running up to within 90 feet of the fort. But Rebel sharpshooting caused work to be abandoned at this sap, and Grover’s siege approach was altered to the northwest face of Priest Cap, with two quarter-mile-long parallels.

The Surrender of Vicksburg

Another great trench was built on the extreme left, on a bluff opposite the Citadel. It was log covered and large enough to accommodate several hundred sharpshooters and five batteries. The saps were buttressed by thick walls of cotton bales that made it safe from southern marksmen. Frequently, the defenders tried to burn the cotton bales by shooting flaming arrows or venturing forth from their lines to light them with firebrands. At all points, events settled into a desultory routine of sharpshooting, round-the-clock bombardment, and trench raids. “The heat, especially in the trenches, became almost insupportable, the stenches quite so,” a staff major recalled. “The brooks dried up, the springs gave out, the creek lost itself in a pestilential swamp, and the river fell, exposing to the tropical sun a wide margin of festering ooze. The illness and mortality were enormous.”

Demoralized, physically beaten down, and diminished in numbers, the Army of the Gulf was a shadow of its former self. Banks reported that he was down to 14,000 effectives, including 22 regiments of nine-month volunteers whose enlistments expired at the end of August. Men whose time was nearly up did not feel like undertaking any more desperate service, and discontent reached the level of mutiny in at least three Massachusetts regiments. Many officers vowed never to go into battle with Banks.

In the end, an event over which they exerted no control made the fall of Port Hudson a certainty. In the early morning hours of July 7, a Union ship carried the stunning news that Vicksburg had surrendered to Grant on July 4. The news spread quickly. The celebration was so intense that the Confederates across the way inquired about all the fuss. Told that Vicksburg had surrendered, Gardner requested documentary evidence. Port Hudson’s survival was inextricably woven with the Mississippi bastion, and Gardner decided that the time for his own capitulation had arrived.

He and his brave little band of defenders had performed incredible strategic and tactical feats in the face of overwhelming odds, inflicting 4,363 casualties at a cost of only 623 of their own. Final details were worked out by July 9, when the besiegers marched in and took possession. On July 16, one week after the fall of Port Hudson, the unarmed ship Imperial tied up at New Orleans and began unloading cargo she had brought unescorted from St. Louis. For the first time in 30 months, the Mississippi was open to Union commerce from Minnesota to the Gulf.

Excellent. Outstanding detail. Needed a map identifying Confederate positions as identified by name in your article. The location of the citadel, the priest cap, and fort desperate should be placed on a map.