By Phil Zimmer

With a sharp clatter of machine guns, the Japanese marines announced their presence by spraying bullets into the isolated U.S. Navy radio shack. Eight Americans dropped to the floor in the early morning attack on Kiska Island, pulled the door open, and crawled free into the dense fog. Two others remained behind to burn code books as machinegun bullets pulverized the radio and shattered the walls of the isolated Aleutian installation.

All 10 of the Navy men were eventually rounded up on the barren, windswept island following the June 7, 1942, attack that came six months to the day after Pearl Harbor. The Americans may have been rudely awakened that morning, but they were not overly surprised. The U.S. base at Dutch Harbor on Unalaska Island, located more than 670 miles to the east, had been attacked June 3-4 by carrier-based Japanese planes. The attacks on Dutch Harbor had created plenty of havoc but did little real damage in the first bombings of North American soil during World War II.

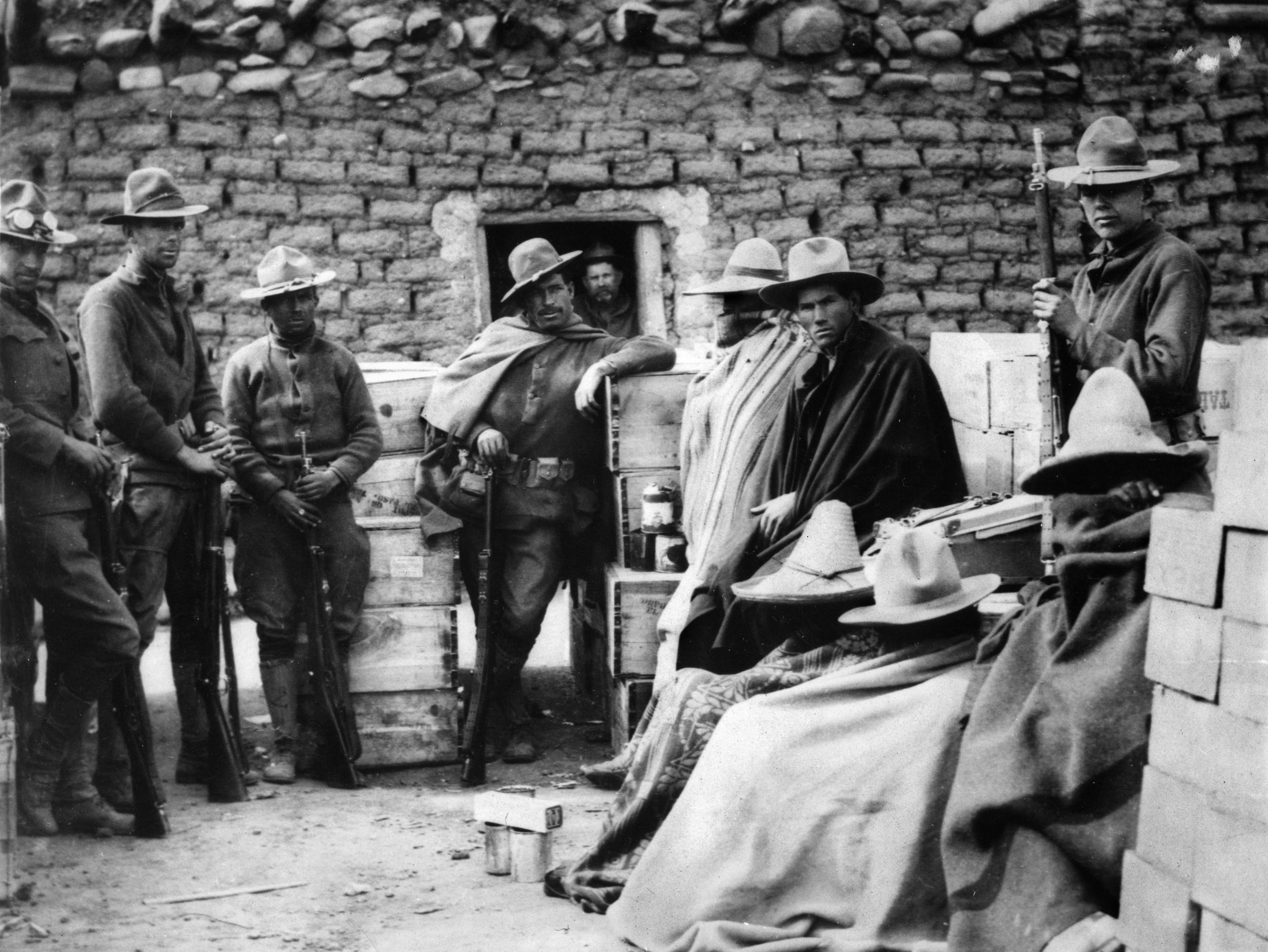

A few hours after the machine-gun attack on Kiska, a component of the Japanese task force steamed into Massacre Bay on Attu, some 175 miles west and the furthermost island in the Aleutians, to discharge another 1,200 troops. With difficulty, the troops made their way over snow-covered passes to take the tiny 41-person village of Chichagof on the island’s northeast rim. Soon both Attu and Kiska were firmly in the hands of more than 2,500 crack Japanese troops on the two islands with a sizable naval force patrolling offshore.

The two fog-shrouded islands in the western Aleutians were taken without any real opposition, with only one person killed in the process. Sixty-year-old Foster Jones, who served as a teacher at Chichagof, was shot down as he attempted a dash to a radio set to alert the American military. The emperor’s forces quickly created defensive positions and set up antiaircraft guns as men and war matériel continued to swarm onto the beaches in a determined move to maintain the claim.

Alaskan Defense Commander Maj. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner Jr., the outspoken son of a Confederate general, had strenuously argued for years that the region was unprepared for war despite Herculean efforts. “We’re not even a second-rate team up here,” he told Washington. “We are a sandlot club.” And that sandlot club consisted of small, isolated Army garrisons, scattered airfields with a few bombers and fighters, and a naval fleet of aging destroyers, submarines, and converted fishing boats. It was tasked with locating the Japanese in the cold, isolated, fog-shrouded Aleutians, strung like black pearls across more than 1,000 miles in the North Pacific.

Before the fighting had died down more than 14 months later, the Americans were to suffer 1,500 killed and 3,400 wounded in the retaking of Attu alone, while the Japanese lost 4,350 killed. Attu was located 650 miles from the major Japanese base at Paramuchiro in the Kurile Islands. Although often overlooked, the Aleutian Islands campaign was to clearly demonstrate America’s willingness and ability to muster its forces and focus its industrial and military resources to pry the Japanese from American soil.

The June 3-4, 1942, attacks on Dutch Harbor were seen by many as a diversionary strike by the Japanese in their concerted thrust to take Midway atoll. Because the Americans were secretly reading the Japanese codes, they set a trap at Midway that succeeded well beyond expectations, in part because of flukes in the timing of the American attacks. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto lost all four aircraft carriers committed at Midway along with more than 325 planes, one third of Japan’s combat pilots, and thousands of sailors as Japan suffered its first major naval defeat in several hundred years.

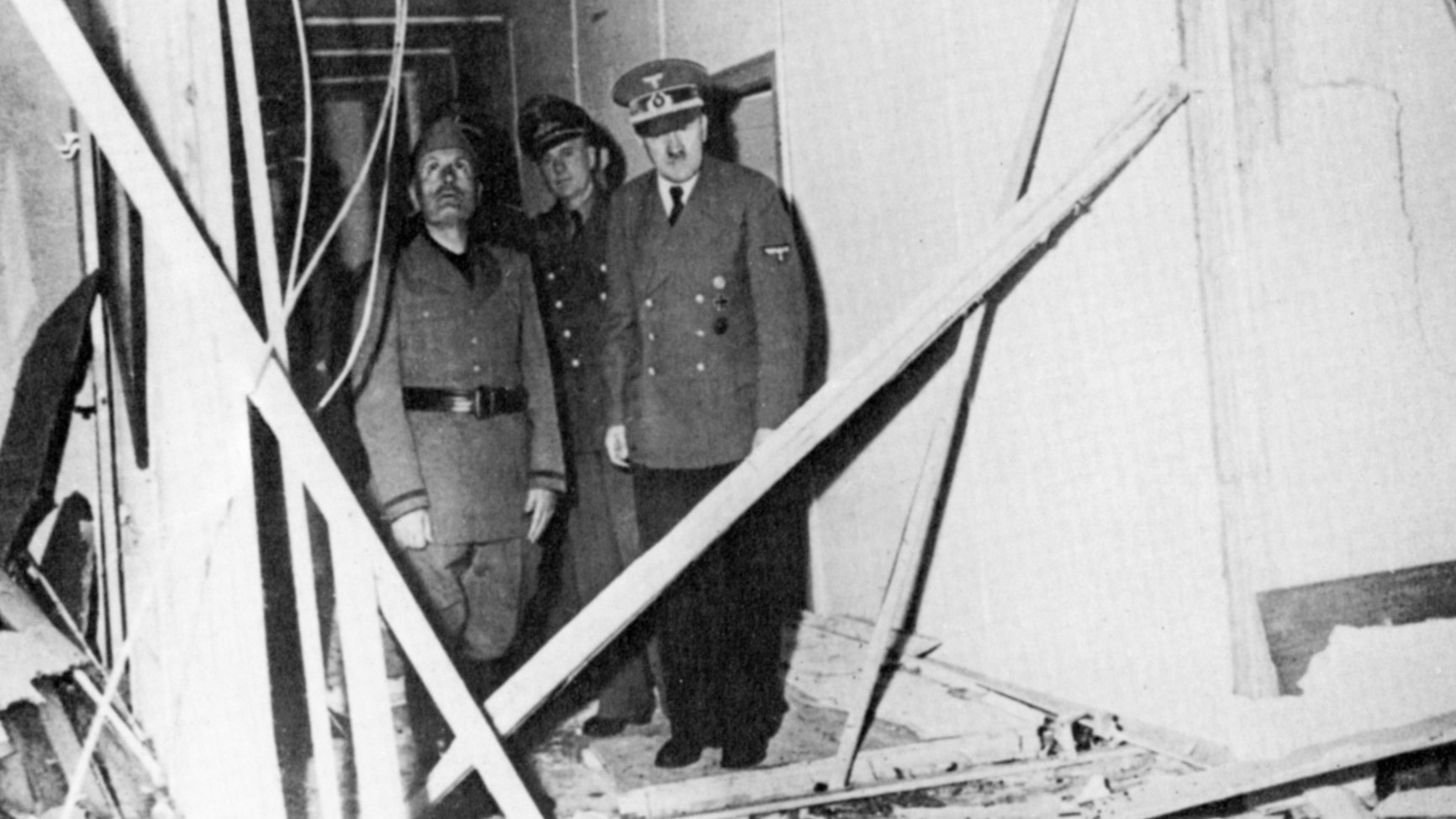

In hindsight, the two aircraft carriers and the planes committed to the strike in the Aleutians might have easily tipped the scales in Yamamoto’s favor at Midway. Following Midway, the Japanese were determined to make a statement by maintaining a hold on the western Aleutians and perhaps tying up substantial American forces in the process. It would provide a badly needed victory in the wake of Midway, help protect Japan’s northern flank, and perhaps interfere with the flow of Lend-Lease goods to the Soviet Union, thus assisting Axis partner Nazi Germany in its struggle half a world away.

Much of the Aleutian campaign would depend on men like Buckner and U.S. Army Air Forces Colonel William O. Eareckson, an equally bold and innovative thinker who rarely did things by the book. It was Eareckson who directed the American air strikes against the Japanese on Kiska, the closer of the two islands. As the first of the flights approached on June 11, 1942, the well dug in Japanese put their 75mm antiaircraft guns to good use, managing to lay one burst into the open bomb bay doors of the lead aircraft, blowing the Consolidated B-24 Liberator out the air so violently that the two bombers flying abreast were crippled by the explosions. Eareckson personally led the second flight that day, bringing three Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses in at 3,000 feet, well below Kiska’s volcanic peak, and wiggling through tight mountain passes to surprise the enemy from behind. The startled Japanese never found the range as the planes slid in and dropped their sticks of bombs toward the destroyers and cruisers lying at anchor, creating loud explosions but missing the targets.

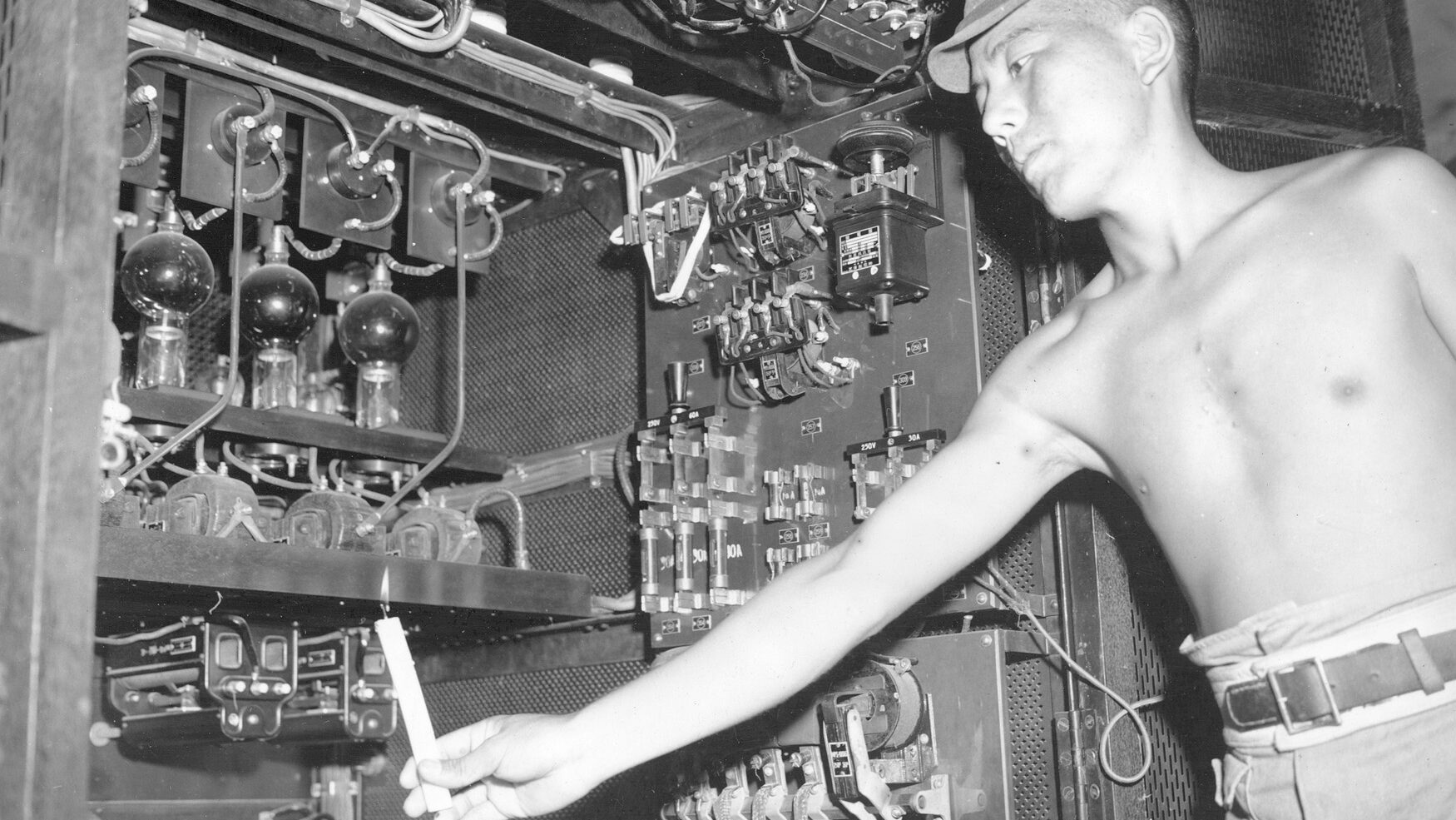

The U.S. Navy took the next shot at the enemy, thanks to the USS Gillis, a seaplane tender serving as the mother ship to 20 Consolidated PBY Catalinas. The crew of the tender had double the usual number of planes to repair, refuel, and rearm at Nazan Bay on Atka.

The Kiska Blitz continued with bombing by both the Army Air Forces and the Navy. The U.S. attacks took their toll as ships were damaged, three large Mavis seaplane bombers were sunk at anchor, and a number of 75mm guns were silenced. The Americans suffered too, with more than half the lumbering PBYs shot down or put out of action within the first three days. The Navy pilots were relentless. The PBYs continued with strikes on the island as the men on the tender worked around the clock servicing planes before they headed back to what the pilots grimly called the “PBY Elimination Center” at Kiska. By June 13, the bone-weary men on the USS Gillis had run out of bombs, ammunition, and fuel for the planes, so the tender was ordered away from Atka.

The campaign was now 11 days old with the Japanese in possession of the western portion of the Aleutians, and no American forces were positioned west of Umnak. It was now a Mexican standoff in the cold, fog-shrouded North Pacific. Japan was afraid of an American invasion of the freshly won islands, and the United States was wary of further Japanese advances on American soil.

In the wake of Midway, the Japanese decided to hold their Aleutian islands for a few more months to tie up American forces and then abandon their gains with the arrival of winter. In early June a large Japanese force consisting of four carriers and a sizable fleet of cruisers and destroyers steamed from Paramuchiro to support and resupply the islands.

The resourceful Eareckson and his men now devised what they called dead-reckoning runs to offset the foggy conditions that most often prevailed at Kiska. The American pilots used a compass and stopwatch as they swung by the volcanic peak and dropped their payloads through the cloud cover. Not much damage was done, but the raids delayed construction work on an airfield. Eareckson devised another clever gambit to snare Japanese pilots. He used radar-equipped B-17s to escort newly arrived Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighters to Kiska and then directed the fighters down through the clouds to tangle with enemy bombers before swinging down to attack ground targets. On August 4, 1942, P-38s used a radar assist from a B-17 to dive from the clouds and send two Kawanishi 97 patrol aircraft flaming into the sea.

The Americans were gearing up for a protracted fight and instituted Operation Bingo, the first mass airlift in American military history. Tons of men and matériel were airlifted into Nome, Alaska, which provided a new base for Buckner’s men. Nome’s airfield eventually became an important staging area for Lend-Lease aircraft headed to the Soviet Union.

Although the tap had been opened and supplies were flowing from America’s stateside industrial base, the hardships continued largely unabated for the men in the cold, damp climate of the Aleutians. The Japanese faced the same elements and the continuing American bombardment that cratered and slowed work on the Kiska runway.

By August 1942, the Americans were preparing to springboard into the central Aleutians with a landing on Adak, 275 miles east of Kiska. Colonel Lawrence V. Castner and 37 of his men, who belonged to a commando-style scout unit known as “Castner’s Cutthroats,” paddled ashore August 28 in the darkness and alighted from rubber rafts. The scouts searched the island in vain for the Japanese and flagged an all-clear the next day. The main body of 4,500 troops landed August 30 in the midst of stormy weather that smashed boats and sent tons on cargo to the bottom. By the end of the day, Buckner’s 4th Infantry Regiment was ashore and antiaircraft guns were in position along with heavy construction equipment and units from the 807th Aviation Engineer Battalion.

Looking for the best location for the planned airfield, the engineers settled on a tidal cove that could be relatively easily drained and filled. The engineers plowed ahead, completing the airfield in 10 days rather than the three to four months that had been predicted based on Adak’s heavily mountainous terrain. The runway proved to be a fortuitous development for the Americans, bringing them closer to the enemy and eliminating the grueling 1,200-mile roundtrip flight between Umnak and Kiska. On September 14, Eareckson departed Adak for the first time to lead his 12 B-24 Liberators, along with 14 P-38 Lightnings and 14 Bell P-39 Aircobras, on a wave-top strike. In the stunning surprise attack, the Americans sank two ships, damaged three others, put three midget submarines out of commission, silenced a dozen antiaircraft guns, and set a number of shore installations on fire. Seven Japanese interceptor-fighter floatplanes known as Rufes were damaged at anchor, and another five were shot out of the air by American fighters.

Soon the base at Adak was handling tons of incoming supplies each day, and Buckner was considering taking the battle directly to the Japanese homeland. Seabees descended on the island, building an entire city complete with Quonset huts, kitchens, power grids, and roads. It was not an easy process; Seabees were often tied to rafters of buildings they were constructing so they would not be blown off by the fierce Aleutian winds. Throughout the construction, pressure on the enemy was stepped up with Canada’s 111th Fighter Squadron joining in the raids on Kiska.

The Japanese did not discover the Adak base until September 30, a full month after the Americans had landed. The few enemy planes that attempted a run at Adak were simply shot out of the sky. With things going badly for the Japanese at Guadalcanal, there were no planes and no additional matériel for the Aleutian effort. The Japanese would need to hold on until winter and then fall back to bases in the Kurile Islands. Meanwhile, the 1,500 Japanese troops on Attu were repositioned to Kiska.

Word came down that the Aleutians would not be abandoned as planned by the Japanese but would be held fast. Plans were afoot to reoccupy Attu with fresh troops and to build a runway there, too. The Japanese retook Attu on October 29 and were not discovered until two weeks later by the Americans. Eareckson established Attu as an alternate bombing site if Kiska was socked in by bad weather. The Americans continued to put pressure on the two islands with bombing runs that destroyed planes, damaged installations, and delayed construction.

By December 1942, Bucker had some 150,000 troops in the theater. Dutch Harbor was now handling more than 380,000 tons of shipping each month, and a 1,000-mile pipeline brought Canadian oil to Alaska. The new Alcan Highway ran more than 1,500 miles and connected Alaska by land to the continental United States. It served as a vital Lend-Lease link to Russia and brought supplies to Buckner’s men.

Interservice squabbles continued, with Buckner at odds over what he believed to be the Navy’s reluctance to bring its full resources to bear on the enemy. A shift occurred in January 1943, when Rear Admiral Thomas Kinkaid, a vigorous veteran of several Pacific battles, assumed command of the U.S. North Pacific Force with responsibility for the Aleutians. Kinkaid brought a bold new approach with him. Interservice cooperation improved as the operations shifted to a higher gear.

On his second day in command, Kinkaid ordered full landings to proceed at Amchitka, 75 miles southeast of Kiska, while the Army Air Forces pinned down the enemy with bombing of Attu and Kiska and sank two heavily laden enemy freighters in the process. The Amchitka landings went well, and the Japanese did not spot the American intrusion until January 23, 1943, when they began bombing runs known as the Amchitka Express. The Japanese air raids, which consisted for the most part of attacks by two aircraft, lasted several weeks but did little damage.

When the Seabees completed the runway at Amchitka, Colonel Jack Chennault, son of General Claire Chennault, the legendary founder of China’s Flying Tigers, brought a flight of Curtiss P-40 Warhawks to the new strip. When two Japanese floatplanes took flight on January 29 from Kiska, Chennault’s men shot them from the sky. The Japanese air attacks became sporadic after that, largely because they had so few airworthy planes left. Ten P-38s joined the party at Amchitka, along with North American B-25 Mitchell and Martin B-26 Marauder medium bombers and a PBY tender. By the end of March, Amchitka airfield had been extended and the veteran 36th Bombardment Squadron and its heavy bombers joined the others as the Americans stepped up bombing and laid plans to establish a naval blockade of Kiska and Attu.

Rear Admiral Charles McMorris had only four destroyers and the cruisers USS Richmond, his flagship, and USS Salt Lake City to enforce the blockade. Reviewing his options, he decided to shell Japanese positions at Chichagof on Attu before steaming farther westward to intercept Japanese convoys before they neared the two Japanese-held islands. The Americans intercepted and sank a 3,000-ton supply vessel en route to Attu, which compelled two other Japanese ships departing the Kurile Islands to turn back.

By moving westward to Amchitka the Americans had raised the stakes. By January 1943, they had a clear advantage in planes, bombs, and men. Finishing the runways on Attu and Kiska would be an option for the Japanese, but using warships or submarines to attack the extended American supply lines was ruled out. The Japanese did not have large surface ships available, and they stood firm in their belief that submarines should be limited to running supplies to outposts or attacking American warships.

Japanese headquarters prodded the estimated 8,000 men on Kiska and the 1,000 on Attu to redouble their efforts to complete the airfields, even as they were hampered by continued American bombing and the lack of construction equipment. The situation worsened as the Americans tightened their hold, continued the bombing, and downed more enemy planes. One Japanese transport ship with three bulldozers aboard managed to squeak into Attu’s harbor only to be sunk before the eyes of the construction workers. A few supply ships did make it through, but others were turned back by the American blockade.

At that point, the Japanese decided to commit more forces. Admiral Boshiro Hosogaya would take his Northern Force consisting of four destroyers and four cruisers, along with three heavily loaded transports, and blast his way if necessary from the Kurile Islands to the Aleutians. In the Battle of the Komadorski Islands, fought March 27, 1943, the Japanese damaged the aging USS Salt Lake City, rendering it dead in the water. The aggressive McMorris called for a smoke screen to protect the venerable ship and ordered three destroyers forward to attack the larger enemy ships. As the USS Monaghan and USS Coghlan closed to within 9,000-yards of the cruiser Nachi, the Japanese flagship turned tail as American salvos followed it. Salt Lake City managed to get under power as the Japanese disappeared over the horizon. The Japanese Navy had been forced from the scene, and no further convoys were to reach the Aleutians.

The Americans had decided by January 1943 to take Kiska with an amphibious landing force using Army troops. The brass ignored the advice of Alaskan veterans, who called for a comparatively light-footed, fast-moving infantry force over a traditional, heavily equipped unit on the island’s soggy surface. They did accept one crucial piece of advice from the Aleutian veterans: the 4th Infantry Regiment and the National Guard units already in Alaska were too depleted and too small to accomplish the mission.

The U.S. military designated the Army’s 7th Motorized Division, at the time in desert training in California, as the unit for the job. The planned move against Kiska was just three months away, so the division faced a challenging transformation from a desert warfare motorized division to a light infantry division equipped and trained for amphibious landings in the cold, windswept Aleutians. In the process, the unit’s motorized equipment was withdrawn, and it was designated the 7th Infantry Division.

Veterans of the Aleutian campaign were able to convince the planners that 75mm pack howitzers should be included with the heavier 105mm howitzers. Equipment and supplies would need to be manhandled over Kiska’s muskeg, making motorized travel questionable at best. American ships were in short supply as the Allies were making preparations to land in Sicily and the Solomon Islands. That shortfall prompted the American planners to focus instead on attacking Attu, 175 miles west of Kiska and with only an estimated 500 defenders. The landings on Attu were given the go-ahead, and training of the 10,000-man 7th Infantry Division began in California at San Diego and Fort Ord.

Strained relations continued between the leaders in California and the Aleutian veterans. Maj. Gen. Albert E. Brown, commander of the 7th Infantry Division, rejected the idea of a personal reconnaissance of the Aleutians. When one of Buckner’s staff pointed out that all three military branches had poor maps with different coordinates, nothing was done to correct the problem. A large 90mm antiaircraft regiment was added to the growing landing force despite Eareckson’s contention that the Navy’s own antiaircraft batteries were sufficient. Worse yet, the men were not issued proper clothing or boots for the wet, soggy conditions they would encounter in the western Aleutians. Compounding the problems were recent reconnaissance photos that revealed some 1,600 Japanese on Attu, more than three times the previous estimate. That prompted the Americans to plan on putting the entire 7th Infantry Division ashore rather than 2,500 as previously planned. Additional transport craft would need to be scrounged in short order.

A new round of photos showed that the Japanese had 2,500 men on Attu. Planning proceeded, with heavy gunfire to be provided by the battleships USS Nevada, Idaho, and Pennsylvania. Nineteen destroyers, six cruisers, and an escort aircraft carrier would round out the task force.

As late as May 2, 1943, other plans for the invasion were being seriously considered. U.S. strategists agreed on a fairly complicated plan. The Southern Force, under Colonel Edward P. Earle, was to land at Massacre Bay in the southeast, and the Northern Force, under Lt. Col. Albert V. Hartl, was to land three miles north of the main Japanese camp at the western edge of Holtz Bay. The Northern Force was to clear the western section of Holtz Bay, take the high ground along Moore Ridge, and link up with the Southern Force as it pushed north over the crucial Jarmin Pass that connected Massacre Bay and Holtz Bay.

The forces then would complete the capture of the Holtz Bay area and the valley to the southeast. A well-trained and heavily armed scout unit under Captain William H. Willoughby was to land along the north shore west of Holtz Bay and attack east toward an enemy battery at the head of the west arm of the bay. That enemy battery would be forced to turn and fight to the west, weakening its set position overlooking the bay. Another small unit was to land at Alexei Point, east of Massacre Bay, to cover the back of the Southern Force as it advanced north toward Jarmin Pass. A reserve unit would wait aboard ship.

Despite the news blackout, the Japanese learned of the invasion plans as the U.S. task force steamed toward Attu in early May 1943. The Aleutian weather did not help, pushing the attack back from May 7 to May 11. Colonel Yasuyo Yamasaki realized he could not defend every inch of the 345-square-mile island, so he pulled his men back from the beaches and into the mountains. He planned to lure the Americans from the beaches and then blast them with mortars and machine guns from the high ground. It would be a delaying action until additional men and matériel could be landed in late May as had been promised by Japanese officials. Despite the cautionary tales from the Aleutian veterans, the leaders of the untried American unit were optimistic that the amphibious landings would go well and most of the fighting would be over within days.

The scout unit landed shortly after 1 am on May 11, paddling ashore in rubber boats from two surfaced submarines. The scouts started working their way inland toward the snow-covered, 3,000-foot mountains. A few hours later men of the Northern Force began landing with difficulty near Holtz Bay accompanied by a small band of scouts, and by mid-afternoon some 1,500 men were ashore. The largest contingent, led by Brown, was delayed by fog before landing unopposed at 4:20 pm. By 5 pm, the Americans had secured all three beaches without a shot being fired.

Once the American heavy guns began landing at Massacre Bay, the tractors pulling the 105mm howitzers broke through the tundra and began spinning wildly in the black mud, just as the Aleutian veterans had cautioned. As the infantry advanced from the bay, sniper fire and enemy mortars rained down on the Americans. The Japanese harassing fire continued for the next five days as the Americans struggled forward against the heavily entrenched enemy. The Japanese were well positioned above Massacre Bay, commanding the heights near Jarmin Pass and along neighboring ridges. Continuing Japanese fire from the ridgelines along both flanks and in front brought the American advance to a halt about 600 yards short of the pass.

The Northern Force also found the going difficult and was stopped a half mile from the hilltop that dominated Holtz Valley. By 10 pm that first day, the Americans had more than 3,900 men ashore including about 2,000 at Massacre Bay, 1,500 north of Holtz Bay, and the scouts to the west.

The next day, May 12, the USS Nevada opened fire, lobbing 14-inch shells into enemy positions above Massacre Bay. The heavy shelling proved deadly effective as evidenced by the mangled equipment and torn bodies of Japanese soldiers that tumbled off the mountain. The tenacious enemy was well entrenched, and confusion on the beach delayed the movement of supplies to the troops fighting above the bay. The Americans pressed forward despite heavy enemy rifle, machine-gun, and mortar fire. They managed to get to within 200 yards of the mouth of Jarmin Pass on May 13 before being forced back to their starting point some 600 yards short of the pass. The Southern Force made five successive attempts to take the pass but the units were pushed back.

A frustrated Brown called on his auxiliary troops for the fray above Massacre Bay and requested additional troops from Buckner’s men on Adak. Confusion on the landing beach had not been resolved at Massacre Bay, and static and the chaos of battle had interrupted communications with Navy officials aboard ships off the coast. The Army was blaming the Navy, and the Navy blaming the Army for missteps in the battle that was to have been won in a matter of days. Brown was relieved, and Maj. Gen. Eugene M. Landrum, former commander on Adak, took charge on May 17 of all forces on Attu. Colonel Lawrence Castner of the Alaska Defense Command became Landrum’s deputy chief of staff.

Incredibly, during the first five days of fighting no contact had existed between the two U.S. main forces. Each knew the other had landed, but they had no detailed information beyond that. On the afternoon of May 16, the Northern Force had seized the high ground on the western section of Holtz Bay that dominated the main Japanese base. The Japanese moved to the eastern arm of the bay, exposing their forces at Jarmin Pass to the prospect of being taken from the rear by the advance of the American Northern Force. During the night of May 16-17, the Japanese commander pulled his troops from the left flank of the Southern Force to behind Jarmin Pass in the direction of Chichagof. In the process, he strengthened the defensive positions around Clevesy Pass that also led toward Chichagof. By May, 18 the Northern and Southern Forces had linked up, ending the fight for Jarmin Pass.

The struggle to capture Clevesy Pass and the new principal Japanese base at Chichagof had begun. The plans now called for the Southern Force to take Clevesy Pass while the Northern Force fully cleared the eastern arm of Holtz Bay and then advanced toward Chichagof along the northern slope of Prendergast Ridge. It took three days of fierce fighting before Clevesy Pass was cleared and the Northern Force had reached the halfway point along the ridge on its way to Chichagof.

Intelligence revealed that the Japanese might land reinforcements, so the 1st Battalion, 17th Infantry Regiment was tasked with setting up a strong defensive position at Holtz Bay. Reinforcements never did reach Attu, and it is still not certain if they ever even set sail for the embattled island. A flight of 10 low-flying planes did appear on May 22 and launched 12 torpedoes, which missed their marks on the cruiser USS Charleston and the destroyer USS Phelps off Massacre Bay. Sixteen heavy bombers appeared the same day off Chichagof Harbor. P-38s arrived on the scene, and they fled, but not before nine Japanese bombers were reported shot down. With the exception of these two abortive air attacks, the Japanese forces on Attu were to receive no outside assistance.

The Southern Force took heavy fire as it moved toward Sarana Nose on the way to Chichagof. On May 22, the Americans unleashed four batteries of 105mm howitzers, a section of 75mm pack howitzers, 23 81mm mortars, 14 37mm guns, and heavy machinegun fire on Sarana Nose. As troops of the 17th and 32nd Infantry Regiments advanced, they discovered that the enemy had moved farther up the hill. Many Japanese were so dazed and shaken that they offered little resistance as the Americans took the hill.

Concurrent with the struggle for Sarana Nose, the 1st Battalion, 4th Infantry Regiment encountered the enemy on the slopes of Prendergast Ridge. The unit called in 105mm howitzer support, driving the enemy from cover so the Americans could take the slope and reach the summit of the ridge. The taking of the ridge and Sarana Nose opened the way for a direct attack toward Chichagof Valley. U.S. forces captured an area at high elevation known as the Fish Hook by May 28 in a methodical advance. For their valor, Companies I and K, 32nd Infantry Regiment received unit citations.

The Japanese had their backs to the sea and were crowded onto a flat area at Chichagof Harbor. The well-armed Americans held the dominating heights around the harbor and had a powerful naval force just offshore. On the night of May 28, for the first time since the beginning of the battle, the Americans had no reserves in place as Landrum prepared to launch his full force against the trapped Japanese on the 29th.

Yamasaki had fought a skillful delaying action over the previous 18 days, giving ground only under substantial pressure and losing some 70 percent of his force in the process. He had lost most of his artillery and much of his supplies in the defense of Holtz Bay. He had also lost hope that the promised help would come from the Kurile Islands, and he was aware of the dire straits of his position. Yamasaki assumed that the powerful force confronting him was prepared to pounce on his bone-tired, battle-weary, undernourished command.

Surrender was not an option for him. A suicidal last stand would be useless and fruitless, and an attempt to infiltrate into the hills would only delay matters for a few days. A surprise counterattack, though, offered a glimmer of success. Using the cover of darkness, he might be able to deploy his remaining force to cut through to the American battery positions on the heights behind Engineer Hill. Those guns could be turned to destroy or capture the main American base at Massacre Bay. It was a long shot. It would result in either victory if it worked or a certain but honorable death if it did not. Yamasaki called his more than 800 men together and planned the attack.

At 3:30 am on May 29, Yamasaki’s men swarmed into a company of Americans as they were withdrawing under orders. The shrieking Japanese struck with bayonets fixed at the outnumbered American unit, throwing it into confusion and sweeping across Sarana Valley toward Clevesy Pass. U.S. combat engineers, cooks, and other service units heard the confusion and sprang to arms. They quickly organized an improvised line on the slopes Engineer Hill.

A small number of Japanese managed to penetrate Clevesy Pass and attack an area in Massacre Valley just short of the American 105 mm howitzers. Some fighting continued there on May 29, but much of the onslaught was defeated in hand-to-hand combat by the engineers. Late on the afternoon of May 30, matters were well in hand with units of the 17th and 32nd Infantry Regiments taking Chichagof Harbor without resistance.

After the battle, reporter Robert Sherrod walked the ground covered by Yamasaki’s charge and counted the bodies of more than 800 enemy soldiers. “The results of the Jap fanaticism stagger the imagination,” wrote Sherrod. “The very violence of the scene is incomprehensible to the Western mind. Here groups of men had met their self-imposed obligation, to die rather than accept capture, by blowing themselves to bits.” He estimated that one in four held a grenade against his head. “Sometimes the grenade split the head in half, leaving the right face on one shoulder, the left face on the other,” wrote Sherrod.

One American report notes that a tribute to Yamasaki’s garrison lies in the statistics of the Attu campaign. More than 15,000 American soldiers participated in the attack with 549 killed in action, 1,148 wounded, and another 2,100 incapacitated. The Americans buried more than 2,350 Japanese with an undetermined number of additional enemy soldiers buried by their own during the fighting. Perhaps the U.S. Army’s official history puts it best: “In terms of Japanese destroyed, the cost of taking Attu was second only to Iwo Jima. For every 100 of the enemy on the island, about 71 Americans were killed or wounded.”

There were a few benefits to the fight for Attu. The Americans learned valuable lessons about naval gunfire support, mountain operations, unloading transports, and upgrading tactical procedures. The lessons helped save American and Allied lives throughout the remainder of World War II and also in the Korean War.

While the infantry carried much of the weight of the battle, the artillery, Army Air Forces, and Navy played crucial roles by opening the way for the foot soldiers. The combat engineers deserve credit not only for their stand against the final Japanese charge, but also for constructing the airfields and installations that played a vital role in the outcome.

With Attu firmly in American hands, only the fortress at Kiska remained to be taken. The Americans dramatically stepped up the bombing of the island, and on July 26 alone it was hit with more than 200,000 pounds of bombs. The Japanese decided to abandon the island, burning or destroying anything of value, scrawling insults to the Americans, and setting booby traps before the approximately 5,200 defenders departed in late July 1943, aboard Navy ships. The Americans were unaware the enemy had left, and they continued the bombardment from air and sea with one flight even detailed to drop surrender leaflets on the now-deserted island.

There were some suspicions that the Japanese had departed. Buckner and others suggested putting a scout unit ashore to check things out, but Kinkaid made the decision for an all-out invasion of Kiska. Even if the enemy had scampered, he contended, the landings would be excellent for training purposes, perhaps in the eventual need to invade Japan itself. An invasion force of more than 34,000 gathered, including Canadian forces. The troops began landing August 15, 1943, with a doubting Eareckson promising a case of good Scotch to anyone who could find even a single Japanese soldier on the island. His hunch proved correct, and after combing the island, not one enemy soldier was located, although tons of munitions had been expended and more than 300 casualties incurred in the landings.

The Aleutian campaign gave the United States its first theater-wide victory in World War II. The Japanese were now off North American soil, and their venture into the Western Hemisphere was concluded. From that point forward, the United States and its allies continue their focus on tightening the noose around Japan’s home islands.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments