By Eric Niderost

Prince Rupert of the Rhine did not like to be kept waiting, especially when each passing minute seemed to lessen his chances of victory. It was July 2, 1644, and the prince was facing a rebel army of Parliamentarians and Scots that outnumbered his own Royalist forces. But Rupert knew that if he attacked quickly, and without warning, the advantage of surprise might tip the scales in his favor. To that end, he had sent an order to William Cavendish, Marquess of Newcastle, to join him at Marston Moor. Newcastle commanded troops at York, about seven miles away.

Newcastle’s cavalry belatedly showed up at about 9 am, and the marquess himself arrived with a small troupe of “gentlemen of quality” at about the same time. Rupert’s original orders required Newcastle to start his march at the predawn hour of 4 am, but it was obvious that command had been ignored. Prince Rupert somehow controlled his temper, merely remarking, “My Lord, I wish you had come sooner with your forces, but I hope we shall yet have a glorious day.”

The prince also saw that Newcastle’s infantry was still absent. Unfortunately for Rupert, many of the Royalist soldiers back in York were busy plundering an abandoned Parliamentary-Scottish camp. The situation was further complicated by the fact that Newcastle’s infantry was led by James King, Lord Eythin. Eythin hated the prince, and the feeling was mutual. Eythin and Newcastle may have been deliberately dragging their feet. The prince was still in favor of an immediate attack, but Newcastle demurred.

Newcastle said that he had intelligence that there was some discontent between the English and Scots in the rebel army. Surely the seeds of discord would cause the two allies—strange bedfellows indeed—to go their separate ways. Then, too, the allied Parliamentarian-Scottish army was very large, even larger counting camp followers, servants, and others. Newcastle argued that they could not supply such a host for much longer—they would have to separate soon.

There was some truth to these arguments, but Rupert’s instincts were sound. Delay might well be fatal to any hope of victory. Every hour the Parliamentarians grew stronger as more units joined their comrades at Marston Moor. Rupert decided they would wait, even though it was against his better judgment. He may have also felt he needed Eythin’s troops from York, and they had still not arrived.

About 2 pm, the Parliamentarians opened up a small cannonade, a weak barrage of exactly four shots. A Royalist officer, Sir Henry Slingby, noted that they were merely “showing their teeth,” and no damage was done. But a skirmish took place that foreshadowed the future outcome of the battle.

The Royalists tried to seize a position that would have helped them enfilade the Parliamentarians but were sent packing by cavalry from the Eastern Association led by Lt. Gen. Oliver Cromwell. Parliament attempted to bolster recruiting by dividing its territories into groups called associations. The Eastern Association consisted of East Anglia and the counties from Lincolnshire to Hertford.

Oliver Cromwell was a country squire and member of the gentry, owning lands in Huntington. He was a fanatical Puritan, but he was also a brilliant soldier with a growing reputation. It is said that earlier in the day, a Parliamentary prisoner was brought before Prince Rupert for questioning. Rupert promptly asked, “Is Cromwell over there?”

Eythin finally showed up at 4 pm with infantry and a bad attitude. He promptly criticized Rupert’s dispositions, saying they were too close to the enemy. Rupert proposed two courses of action: either attack at once (he still hadn’t given up hope) or move the troops back. Eythin became petulant, declaring it was too late in the day to make such a move—not adding that he was partly responsible for that situation.

A second council of war, which included Rupert, Eythin, Newcastle, and Lord George Goring, was hastily assembled. Goring had a reputation for loving the bottle, and in fact was probably an alcoholic, but he was a fine soldier and sound leader in spite of his vices. Much seems to have been discussed, including the terrain, the wind, and the position of a slowly descending sun.

The debate ended when Rupert decided to give battle the next day. It was now about 5 or 6 pm, and he felt it was too late to start a major engagement. This flew in the face of logic because it was summer and there were still some hours of daylight left. Perhaps the weather played a part in his decision because ominous dark clouds were moving in. Before long the area was drenched in a thunderstorm.

In any case, the Royalist troops were told to stand down, and they started to kindle cooking fires for an evening meal. Rupert himself withdrew to the rear for dinner, and Newcastle went back to his carriage to enjoy his pipe.

For a time it did seem as if there would be no fighting that day. The Parliamentarians, many of whom were Puritan, started singing psalms, and thunderclouds loomed above. But the peal of thunder was soon joined by the sound of artillery as the Parliamentary army launched a sudden surprise attack. The Battle of Marston Moor, one of the most decisive clashes in the English Civil War, was about to begin.

The English Civil War had its roots in the conflict that developed between the king and Parliament. King Charles I had many fine qualities. He was conscientious, dignified, and genuinely devoted to his subjects’ welfare. Charles was faithful to his wife—unusual for monarchs of the time—and had a refined taste in art.

Unfortunately, he also believed in the divine right of kings—that he was responsible to God alone for his actions. In the 17th century, absolutism was the norm, and rulers on the Continent would have readily agreed with Charles. But in the last century, Parliament had grown in power and confidence. It was Parliament that voted on taxes and supplied the king with the revenue he needed to run the kingdom. Armed with the power of the purse, the lawmakers increasingly guarded their rights as Englishmen against arbitrary rule.

King Charles tried to settle the matter by not calling a Parliament for 11 years. In those years he grew increasingly high handed in his search for money without Parliamentary consent. The most famous example is ship money. Ship money was a kind of tax levied on port towns ostensibly for the maintenance of the Royal Navy. But Charles began to collect ship money from inland towns; the levy was imposed in 1634, 1635, and 1636.

Ship money taxes were supposed to be for times of dire emergency. After the third levy there was widespread opposition because it looked as if Charles was determined to make this a permanent extraparliamentary tax. Puritans also resented Charles’s devotion to the Anglican Church, which they considered too Catholic and “popish” for their taste. When Parliament was finally summoned in 1640, its members were in a mood to stand up to the king and his absolutism.

The civil war broke out in 1642. A majority of the nobility and a substantial number, though not all, of the landowning gentry rallied to the king. Generally speaking, the south and east favored Parliament, the north and west the king. The business and commercial classes in the towns supported Parliament. London was a major parliamentary center. Parliament also controlled the sea through the navy.

Parliamentary forces did not fare so well for the first year. They were defeated at Edgehill, which was the first major battle of the war. Charles established his headquarters at Oxford in central southern England and gathered more recruits. He named his nephew, Prince Rupert, General of Horse, essentially commander of all Royalist cavalry. It may have seemed like royal nepotism, but at 23 Rupert was a seasoned and talented soldier who had seen service on the Continent.

Rupert was a splendid figure “clad in scarlet very richly laid in silver lace and mounted on a gallant Barbary horse,” said an eyewitness during the war. His constant companion was Boye, a white hunting poodle quite unlike the French poodle of today’s popular imagination. As Rupert’s fame as a cavalry commander grew, Puritan propaganda insisted that the dog was a familiar, an evil link to the Devil, much as witches had black cats. Puritans claimed Boye was really a little demon who protected his master’s life and sometimes became invisible to scout out enemy positions.

In 1643, the king seemed on the verge of winning the war. The Marquess of Newcastle occupied Lincolnshire, and the king’s forces captured Bristol in July. Other Royalist forces overran Cornwall and Devon, except for a few walled towns. Parliamentary general Sir Thomas Fairfax made a thrust at Oxford, but his offensive ran out of steam and he was forced to withdraw. Queen Henrietta Maria rejoined the king at Oxford with reinforcements and welcome supplies.

Heartened by these events, Charles planned a three-pronged attack on London. But holdout Parliamentary towns were thorns in the king’s side, forcing him to reconsider. Newcastle did not like the idea of moving south on London when the city of Hull was untaken and possibly threatening his rear. Charles decided to abandon his London offensive and turned to besiege the city of Gloucester. When Fairfax marched to the relief of the city, Charles abandoned the siege and turned to face him at the Battle of Newbury. Technically it was a draw, but the king had lost more men than the Parliamentarians.

Both Charles and Parliament started looking for allies to help decide the issue once and for all. The king looked to Ireland and hoped to forge a link with Irish Catholic rebels. He signed a secret treaty with the Irish Catholics, readily agreeing to major concessions in return for military aid. Unfortunately for the king, a copy of the document was captured by Parliamentary forces, and disclosure of the treaty terms brought great discredit on Charles. To most Puritans, being in league with Irish Catholics was akin to being in league with the Devil.

But Parliament was also seeking foreign help, in its case looking to Scotland. Proud and independent, the Scots were traditional enemies and had fought the English intermittently for centuries. But this was the 17th century, and religion was bound to play a major role in any negotiations. Scotland was mainly Presbyterian and had great religious, not necessarily political, ambitions. Scottish Presbyterians naturally entered into negotiations with their English counterparts, and a deal was soon struck. In the Solemn League and Covenant, Scotland agreed to enter the war on the Parliamentary side.

In January 1644, a large Scottish army of some 24,000 men crossed over the border into England. These “Covenanters” were commanded by Alexander Leslie, the Earl of Leven. He was an experienced soldier, having seen service with the Swedes in the Thirty Years War. Newcastle, who led the main Royalist forces in the north, was immediately thrown onto the defensive.

York was a major prize, so important it was sometimes called the capital of the North. Its loss would be a major blow to the Royalist cause, so Newcastle eventually fell back on York, determined to protect it as best he could. He did allow most of his cavalry under Lord Goring to escape the city before the siege began. That left him with some 800 cavalry and 5,000 infantry to defend the town.

Newcastle had arrived just in the nick of time. Three days later, the Scots arrived before the city walls, accompanied by a Parliamentary army under Ferdinando, Lord Fairfax, and his son, Sir Thomas Fairfax. York is situated at the confluence of the River Ouse and the small River Foss. At the time, York had the only bridges over the Ouse for a considerable distance. That made investment of the city that much more difficult.

The siege dragged on week after week, and the Scots and Parliamentarians—sometimes called the Army of Both Kingdoms—must have grown somewhat discouraged. In early June, after an investment of some six weeks, the besiegers were joined by a third allied force, the Eastern Association Army under Edward Montigue, the Earl of Manchester. Manchester’s second in command and general of horse was the formidable Cromwell.

Manchester’s arrival signaled a whole new and more intensive phase of the siege. Before June it had been fairly loose, but with the Eastern Association’s additional men the siege tightened. Playing for time, Newcastle entered into surrender negotiations with the Scots and Parliamentarians. It was a somewhat transparent ruse, but it worked. A general assault was delayed from June 8 to June 15.

Finally wearying of Newcastle’s dissembling, the allied armies launched a general assault on June 16. The Parliamentarians detonated a mine against one of York’s walls, apparently blowing a hole that was considered practicable for an attack. Maj. Gen. Lawrence Crawford of the Eastern Association led an ill-coordinated assault that turned out to be a bloody repulse. Parliamentary forces were badly mauled, and the York garrison actually took 200 prisoners in the bargain.

This success must have heartened the defenders, but it was only a matter of time before they would run out of food. No city can hold out indefinitely, and a place as important as York would have to be relieved. Actually, help was on the way, but because Newcastle was successfully holding his own there seemed to be no urgency. A relief force under Prince Rupert was heading north in a leisurely fashion, attending to other concerns along the way.

King Charles had realized that York would need help as early as May. Charles summoned a council of war at his headquarters at Oxford to work out the details. Prince Rupert was to go north with a small force that would grow along the way as fresh recruits were mustered and additional units met him en route.

One of Rupert’s principal tasks was to secure Lancashire for the Royal cause. This was important because from the Royalist point of view Lancashire was the gateway to Ireland, from which Charles still hoped to import fresh troops, Catholic or otherwise. Rupert set out from Shrewsbury with a small force on May 16, gathering forces along the way. He forced a crossing of the River Mersey at Stockport and stormed Parliament-held Bolton.

It was at Bolton that Rupert’s reputation was tarnished by an alleged massacre. The garrison adamantly refused to surrender, and by the rules of war at that time Rupert had every right to take the city by storm. Some 1,600 troopers and citizens were allegedly killed, and Puritan propagandists had a field day blackening the prince’s name. Rupert then rested at Bury, and was joined by Goring and the York cavalry that had escaped the siege.

The prince also was joined by fresh regiments raised by the Earl of Derby. Bypassing the rebel stronghold of Manchester, Rupert marched to Liverpool. Liverpool was taken after a siege lasting five days. But in mid-June Rupert received a letter from King Charles that played a major part in the unfolding drama.

“If York be lost,” the king’s missive read, “I shall esteem my crown little less.” This was a clear signal to the prince of York’s vital importance. “But if York be relieved, and you beat the rebels’ armies of both kingdoms,” the king continued, “which are before it, I may possibly make a shift upon the defensive until you come to assist me.”

The letter was ambiguous, but a man of action like Rupert was bound to think it meant he was ordered to take on the Scots-Parliamentary army and also relieve York. After the letter was sent, one of the king’s officers, Sir John Culpepper, perceptively remarked, “Why then, before God you are undone, for upon this peremptory order he will fight, whatever comes on it!”

The Parliamentarian besiegers were put in something of a panic when it was learned that Rupert was approaching with 18,000 men. The three major besieging armies at York were each separated by the Rivers Ouse and Foss. If Rupert pounced on one army, the other two would find it difficult to come to its aid.

Rupert’s approach to York was nothing less than brilliant. Blocked from using the main old Roman road to York, he executed a flank march of 22 miles to the northeast, in essence circling around the Parliamentarians. He crossed the River Ure at Boroughbridge and the River Sale at Thornton Bridge. These two rivers form the River Ouse. Later, Rupert’s cavalry surprised and defeated a party of Manchester’s dragoons which had been detailed to guard a bridge of boats across the Ouse at Poppelton.

The Parliamentarian-Scottish army lifted the siege on June 30 to meet Rupert in the field. The army abandoned its camp, which held an abundance of ammunition and supplies, including 4,500 pairs of new shoes. The temptation was too great for Newcastle’s men as they emerged from behind York’s walls. They began looting the camp, which added to the delay in joining Rupert’s army at Marston Moor.

Even with the arrival of Newcastle’s plundering troops that afternoon, the Royalist forces were outnumbered by their foes. Rupert had around 18,000 by most modern estimates, and the Scots-Parliamentarians 28,000. More than 45,000 men were thus present on the battlefield, making it one of the largest ever fought on British soil.

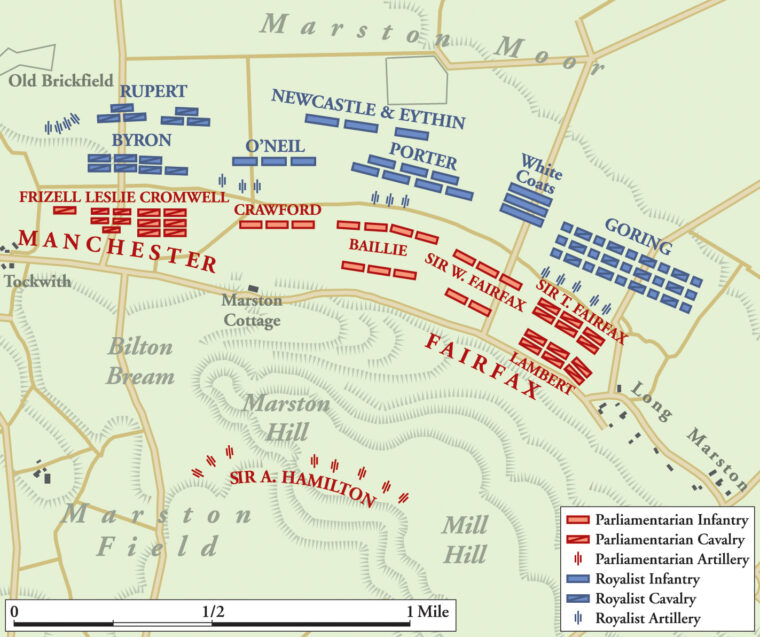

The allied army had the advantage of slightly higher ground, a ridge that stood above a moor. The Royalist army positioned itself on the moor in a concave line almost two miles long, facing south, and positioned in front of a ditch. This ditch line was manned by a party of Royalist musketeers some have described as a “forlorn hope.” Their duty was to fire and retire; that is, discharge their muskets to break up an enemy charge, then scamper back to the protection of their main body.

Although the allies had the high ground, parts of the terrain were covered by “cornfields” (the British term for wheat and rye) which might impede the movement of their cavalry. Rupert had taken special note of the drainage ditch that fronted much of the Royalist line, feeling it would be an effective barrier to slow an allied advance at the very least. There was also a hedge near the ditch that would help the Royalists.

The Scots-Parliamentary army’s left wing was mainly cavalry, commanded by rising star Cromwell. Behind Cromwell’s men were Scots horsemen under Leslie. This was the battle that was to give fame to Cromwell and glory to his “Ironside” troopers, but all too often Leslie’s contribution to the victory is downplayed.

The allied center had units from all three armies, although the Scots predominated.There were about 18,000 infantry in the center, pikemen wielding pikes 14- to 16-feet long, and musketeers. The allied right was commanded by Thomas Fairfax, mainly cavalry and dragoons (mounted infantry). Fairfax was in the first line, backed up by a second line under John Lambert and a third line of Scottish horse under Alexander Montgomerie, Earl of Eglinton.

The Royalist army’s left wing was commanded by Goring. It consisted of 1,700 cavalry from the Marquess of Newcastle’s cavalry (dubbed the “Northern Horse”), 400 cavalry from Derbyshire, and 500 musketeers. The center was mainly infantry, pikemen, and musketeers, nominally led by Eythin. The Royalist right, commanded by John Byron, 1st Baron Byron, had two lines. The first was of cavalry and musketeers, the second had a number of regiments, including some that had come from Ireland.

Rupert also had a cavalry reserve, namely 500 troopers of Prince Rupert’s Horse and 140 men of his elite personal bodyguard. The reserve was under Rupert’s personal command and could be used as he saw fit. His horsemen were well trained but had a reputation for bad discipline when their blood was up. In the excitement of battle they would singlemindedly pursue foes even if they were needed elsewhere.

The battle opened with a Parliamentarian surprise attack around 7 pm. Cromwell’s cavalry troopers smashed into Rupert’s right, commanded by Byron. Byron moved up to challenge Cromwell’s Ironsides but in so doing committed a couple of tactical errors. First, he moved over the marshy ground that fronted his position instead of letting the enemy come to him. In so doing, he threw away the terrain advantage he had moments before.

The second error was even costlier. Byron led his troopers forward in such a way that they came between Cromwell’s horsemen and the Royalist musketeers, all but blocking the Parliamentarians from view. The musketeers were unable to give fire support for fear of hitting their own men.

The Royalist musketeers, many of whom didn’t have their matches lit for firing, also had problems due to the suddenness of the allied attack. In contrast to the later flintlock, the matchlock musket featured a long, coiling cord called a match. When the burning end of the match came in contact with powder in the pan, it ignited the main charge through the touchhole. The matchlocks were clumsy enough, but trying to light a match in battle and in wet conditions following a thunderstorm was nearly impossible.

Cromwell’s troopers routed the first Royalist line, and some of Rupert’s right-wing units began to give way and fall back. Rupert himself arrived on the scene accompanied by his reserve cavalry and bodyguard. The sight of their young and dashing commander gave the Royalists heart, and the prince was able to rally his men. The Royalist right stabilized somewhat, and Rupert’s and Cromwell’s troopers fought with a passion hardly equaled on any battlefield. Cromwell himself was wounded in the neck and was forced to temporarily withdraw to get his wound dressed. The situation was saved by the Scottish cavalry under Leslie, which outflanked Rupert’s horse and hit them hard. The Royalist troopers were utterly routed, and Rupert himself only evaded capture by hiding in a beanfield.

In the center, the Parliamentarian-Scottish army met with mixed success. Crawford’s infantry made good progress, overrunning the ditch, and other allied infantry captured four Royalist field pieces. But the right side of the allied center did not do so well. They were mainly Scottish infantry commanded by Sir James Lumsden. Lumsden ruefully admitted later, “They carried not themselves as I would have wished.” Some even took to their heels, running away “in a panic fear.” Scots were seen shouting in their native dialect, “Ways us (woe is us), we are all undone.”

On the whole, though, the allied attacks on the left and center were doing well. The allied right was quite another story. The ground there greatly favored the Royalists. There were ditches and whins (hedges and bracken), which caused great disorder. Fairfax’s troopers were forced to go down Atterwith Lane, a narrow path that crossed a ditch but allowed them to ride only four abreast.

Goring had the foresight to post musketeers in that area, and Fairfax’s troopers were decimated by a storm of lead. Seeing his enemy in such difficulty, Goring led a counterattack that routed most of the allied right wing. Darkness was beginning to fall as half the Scottish infantry and all of Fairfax’s infantry fled the field.

Unfortunately, Goring’s undisciplined troopers either pursued the fleeing Parliamentarians or turned to plunder the allied camp. Their absence or preoccupation with plunder was going to have an impact on the battle’s final outcome. Not all Royalist cavalry dispersed. Some troopers rallied behind Sir Charles Lucas and attacked the right flank of the allied army.

At this point, Cromwell’s men, full of religious zeal and superbly disciplined, swung around to engage the victorious Royalist left. This time the shoe was on the other foot; Goring’s troopers were confused, scattered, and exhausted. They were easily routed. The tables had turned, thanks to Cromwell’s tough cavalry. Once the Royalist cavalry was defeated, attention turned to the king’s infantry.

But Newcastle’s Regiment of Foot, nicknamed “Whitecoats” because of their undyed wool jackets, stood their ground. Their courageous last stand enabled remnants of Rupert’s army to fall back on York. They refused quarter and would not surrender. The musketeers fired, reloaded, and fired until all their ammunition was gone, and the pikemen kept the cavalry at bay with a prickly hedgehog of points. Finally, Colonel Hugh Frasier’s dragoons came up and decimated the Whitecoats with musket fire. There were only 30 survivors when the regiment finally surrendered. Rupert’s army had been destroyed, with more than 4,000 dead.

There was no doubt the king’s cause had received a major blow. The triumphant allied army took 10 pieces of ordnance, more than 4,000 muskets, 800 pikes, and numerous swords, bandoliers, and barrels of powder. According to one report, more than 100 colors (regimental flags) were also taken. The Royalist debacle was complete.

There were about 1,500 Royalist prisoners, including Lucas, Maj. Gen. Porter, and Maj. Gen. Tilliard. York was only a temporary refuge for Rupert and the shattered remains of his army. Eventually, York surrendered and fell into Parliamentarian hands.

But above all, the legend of Rupert’s invincibility was shattered forever. Rupert’s beloved dog Boye, the animal who the Puritans had said was a demon, was killed on the battlefield, a poignant symbol of the prince’s downfall. This was not the end of the Civil War, which dragged on until 1649 and the king’s execution. However, it certainly was the beginning of the end for the Royalist cause, and in some respects the rise of Cromwell as a major military figure and leader.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments