By Kevin M. Hymel

The invasion force was ready. All across the United Kingdom men waited in more than 5,000 ships and hundreds of landing craft. Pilots, crewmen, and paratroopers waited around fighters, bombers, and carrier planes. Jeeps, trucks, tanks, and every type of military vehicle in the Western Allied arsenal stood bumper to bumper, making roads almost impassable. Stockpiles of shells, small arms, and artillery pieces filled almost every field for miles around. The Western Allies were ready to spring across the English Channel and attack Normandy, France, beginning the long-awaited second front.

But before any pilots, sailors, or soldiers could begin their odyssey in the spring of 1944, they needed the “go” signal from the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower. Operation Overlord, D-Day, would land an Allied army on the beaches of Normandy and drive for the heart of Germany. Eisenhower needed weather conditions to be as ideal as possible before he could release his dogs of war.

The conditions had to be, if not perfect, suitable to maximize Allied strength in the air and on the land and sea. Overlord needed six synchronized elements for a successful landing: a late-rising, mostly full moon for pilots to navigate to drop zones; a low tide so frogmen and demolition experts could destroy the hundreds of German half-hidden beach obstacles; calm seas to allow captains and coxswains to deliver the assault forces to the beaches; southerly winds to drive smoke and dust toward the enemy; an hour’s worth of good daylight accompanying the first low tide so bomber crews could plaster the beaches with their bombs; and enough light during the second low tide to provide visibility to the follow-up forces.

Operation Overlord was so enormous that it would begin three days before troops actually hit the beaches. Ships in England’s northern ports pulling up anchors and heading south needed that much lead time. D-Day would require a favorable weather forecast at least 72 hours ahead of the landings and two days following. Those following two days worried Eisenhower and his commanders. It was just too hard to predict weather that far out.

While Eisenhower and his team could coordinate the moon and tides, they had no control over the wind and clouds. The Allies wanted gentle breezes for the assault, 8 to 12 miles an hour—Force 3 winds. Force 4 winds, 13 to 17 miles an hour, would create breaking wave crests and make the airborne drop precarious but tolerable. Force 5 winds, 18-24 miles an hour, would create moderate waves, white caps, and spray and prevent any airborne operations. Force 6 winds, 25-30 miles an hour, would cause long waves, white foam crests, and more sea spray. Anything above Force 6 meant gale winds and very rough seas (the scale goes to 12, hurricanes).

Clear skies were just as important, but cloudy skies were tolerable as long as they were high enough for bomber crews to see the flare markers and sporadic enough for troop carrier pilots to identify their drop zones. Low clouds or a blanket of clouds, known as stratus clouds, would cancel the bomber and airborne forces. The troop carriers needed a cloud ceiling no lower than 2,500 feet, while the bombers needed at least 11,000 if they were going to spot their markers.

Of course, all of those requirements were nearly impossible to count on, but Eisenhower needed to come as close to the mix as possible. The invasion had already been delayed past May of 1944 to gather more landing craft. That put the earliest invasion date in June. Monday, June 5, Tuesday, June 6, and Wednesday, June 7 possessed both the correct tides and moonlight. Those conditions would not coincide again until the period between June 18 and 20.

To choose the exact date, Eisenhower gathered his air, land, and sea commanders at Southwick House north of Portsmouth for seven meetings to find the best launch window for Overlord. Attending the meetings were Air Chief Marshal Arthur Tedder, Eisenhower’s deputy supreme commander; Air Chief Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory, the commander in chief of the Allied Expeditionary Air Force; General Bernard Law Montgomery, the commander of 21st Army Group; and Admiral Bertram Ramsay, the Allied naval commander of the Expeditionary Force.

The commanders’ chiefs of staff also attended: Lt. Gen. Walter Bedell Smith, Eisenhower’s chief of staff who went by the name “Beetle;” Maj. Gen. Frederick de Guingand, Montgomery’s chief of Staff; and Admiral George Creasy, Ramsay’s chief of staff. Leigh-Mallory had two deputy chiefs of staff: Air Vice Marshal James Robb and Air Vice Marshal Philip Wigglesworth. From Eisenhower’s staff were also his chief of operations, Maj. Gen. Harold “Pink” Bull, and his intelligence officer, Maj. Gen. Kenneth Strong. Maj. Gen. Hoyt Vandenberg, the deputy air commander and chief, also attended one of the meetings.

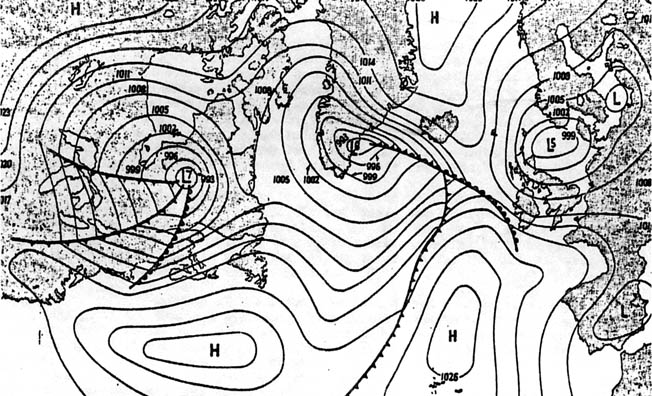

But the most important man at all the meetings was the British Royal Air Force’s Group Captain James Stagg, Eisenhower’s chief meteorological officer. At six-foot-two, the tall, quiet, blue-eyed Scotsman towered over most men. Some found him dour while others considered him sharp minded despite his soft speech. Eisenhower trusted his judgment. When not addressing Eisenhower and his chiefs, Stagg spent most of his time hovering over weather charts for the English Channel, which he had studied as far back as 1894, looking for clues to his forecasts.

Stagg had the difficult task of reconciling three different weather teams: the U.S. Army Air Forces meteorologist group at Widewing, code word for their offices at London’s Bushy Park; the Royal Air Force’s weather team at Dunstable; and the Royal Navy’s team down the road from Southwick House. They would all receive the same information from reconnaissance aircraft and ships in the eastern Atlantic to make their predictions. If they did not all agree on the weather forecast, Stagg had to analyze the three groups’ results and deliver a consensus report to Eisenhower. On May 17, Eisenhower set the day for the invasion tentatively for June 5, but he knew that Stagg’s weather reports would decide the definite date.

Southwick House served as Admiral Ramsay’s battle headquarters. The early Victorian mansion sat nine miles north of Portsmouth on an isolated 360-acre park. While Ramsey occupied the house, Eisenhower, Montgomery, and their staffs occupied the park. Eisenhower lived in a large mobile trailer on the grounds in a wood but used the house as his advance command post. Montgomery had picked it because its surrounding trees disguised the Nissen huts, tents, and caravans that filled the area.

Eisenhower held his weather meetings in a large mess room on the house’s first floor across from a broad staircase. A mahogany table stood at one end of the room while a sofa and cushioned easy chairs filled the rest. Empty mahogany bookcases lined the walls. The officers did not sit around the table; instead they leaned back in the chairs listening to weather reports. Eisenhower preferred the relaxed atmosphere to allow everyone to speak his mind.

The room’s relaxed state contrasted with Ramsay’s operations room next door, which buzzed with activity. Staff officers and British Women’s Royal Navy Service (WRENS) packed the room, coordinating the invasion’s movements once Eisenhower gave the word. A huge plywood map of the invasion filled the entire east wall. On it were the routes the Allied navies would take from southern England to Normandy, along with the locations of German minefields. Here the invasion would be tracked in exact detail.

The map had been constructed by the firm of Chad Valley Toys, but to keep the invasion location secret, the firm was asked to construct a map of Western Europe, from Norway to the Pyrenees. When the map sections arrived at Southwick House, the two delivery men were told to bring only the section that contained Normandy. Since the two men now knew one of the most closely guarded secrets of the war, they were detained in the house until after the invasion.

Eisenhower had begun hosting meetings in Ramsay’s headquarters as early as April to conduct “dry runs,” drilling everyone on how the decision to launch D-Day would go. But the final seven meetings decided the fate of D-Day. Beetle Smith later said of the men at the meetings: “They were not only trying to predict the weather, they were trying to make it.”

FIRST MEETING (Monday, May 29, 10 am)

The first weather meeting took place on a perfectly sunny day. Captain Stagg reported that while the rest of the week should be operationally favorable there was a risk of minor, temporary disturbances during the weekend. Several of the commanders queried Stagg, asking him how long and how intense these “disturbances” would be. He calmly replied, “If the disturbed weather starts on Friday it is unlikely to last through both Monday [June 5] and Tuesday [June 6], but if it is delayed to Saturday and Sunday the weather on Monday and Tuesday could well be stormy.” No one was happy with the forecast.

Stagg knew that the men in the room wanted more definitive answers, but he could not provide any until he processed the next delivery of weather reports. Would they support or contradict his forecast? “Those were the questions that gnawed away inside me during Monday [May 29],” Stagg later wrote.

After the meeting, Stagg reviewed the latest weather reports. What he learned troubled him. Storms appeared to be forming over the Channel just when Overlord was supposed to launch. “I began to fear the worst.” At least Stagg would not have to appear before Eisenhower any time soon. Maybe conditions would improve before the next meeting, scheduled four days later.

As the next meeting drew closer, Stagg’s predictions seemed to come true. The winds picked up around the Channel, and clouds rolled in. He spent his time reconciling his three weather centers. The British Dunstable and Admiralty forecasters foresaw a dark weekend with low clouds varying from day to day through Monday, D-Day. Stagg’s own staff, as well as the Americans at Widewing, were more optimistic, seeing a front moving though the Channel by Saturday, followed by improved weather in the Normandy area “as a finger of high pressure [clear skies]” over the Channel would be protected by an anticyclone [a clockwise cyclone] over the Sea of Azores. Stagg could not reconcile the two outcomes.

SECOND MEETING (Friday, June 2, 10 am)

Friday dawned clear and sunny, just as it had been all week. In the meeting room, Stagg presented a hybrid account of the weather to Eisenhower. While he held close to the Dunstable findings, he did acknowledge the Widewing forecast, which he considered “almost undiluted optimism.” Clouds, he reported, would be prevalent and low while winds would be strong, especially toward the end of the five-day period. The commanders then asked Stagg to clarify his forecast as they sought a window to launch. Throughout the meeting, Eisenhower remained calm. He had time to wait for the weather to change. They were still three days away from D-Day.

After the meeting, Stagg’s meteorologists were still deadlocked about the weather. The Dunstable group foresaw three successive depressions [rains and unstable weather] moving east with winds heading southwest and west. If depression troughs backed the southwest winds, stratus clouds would persist over the Channel. The Widewing group held to their forecast that the ridge of high pressure from the anticyclone over the Sea of Azores would situate northeast though the Channel. This meant some clouds on the British side of the Channel but little on the French side, with no strong winds anywhere in the area. Stagg had to figure out which forecast was more accurate.

THIRD MEETING (Friday June 2, 9:30 pm)

Eisenhower opened the meeting by asking, “Well Stagg, what have you for us this time?” Stagg reported that the situation from the British Isles to Newfoundland had now become “potentially full of menace.” He admitted the last 24 hours had not brought a clearer picture of the situation and that the weather over the Channel would not be what they hoped for. There would be heavy clouds until at least Tuesday, June 6, and maybe into Wednesday. Winds would be coming in from the west at Force 4 and up to Force 5. Maj. Gen. Hoyt Vandenberg asked about weather conditions for the airborne troops. Stagg repeated the information on cloud cover.“It appeared the good weather might break at exactly the wrong moment for us,” recalled Tedder.

Then Eisenhower asked about the weather on Tuesday, June 6, and Wednesday, June 7. After a long pause, Stagg spoke up. “If I answer that, sir, I would be guessing, not behaving as your meteorological advisor.” With his dire forecast delivered, Stagg departed. Just as he had left the room, Rear Admiral Creasy quipped, “There goes six feet two of Stagg and six foot one of gloom.” The remark cut the tension in the room, and everyone laughed. Then Eisenhower addressed the men: “Okay gentlemen, I guess you are all agreed that we carry on until the next meeting.”

Operation Overlord was still on, although the 24-hour window for postponing the June 5 landings was narrowing. The next two meetings would decide the fate of June 5 as D-Day. All around northern England, Allied ships weighed anchor and headed out to sea. Each passing hour meant it would be all the harder to stop their momentum.

FOURTH MEETING (Saturday, June 3, 9:30 pm)

With some of the ships already heading to Area Z—also known as Piccadilly Circus—the zone where the ships would circle as they prepared to cross the rest of the Channel, Eisenhower had to decide whether or not to postpone D-Day. As everyone filed into the room, Stagg told Admiral Creasy, who had joked about his gloom the day before, “I don’t feel much better now.” Once everyone was seated, Stagg and his staff were ushered into the room. “Gentlemen,” Stagg began, “the fears my colleagues and I had yesterday about the weather for the next three or four days have been confirmed.”

Stagg went on to describe the deteriorating conditions over the Channel and across the region. The anticyclone that Stagg hoped would protect the Channel from the Atlantic depressions had given way and could not be counted on to push the depressions northward. Starting the next day, June 4, strong winds between Force 4 and Force 6 would blow to the southwest and west until Wednesday, June 7. Clouds for the next few days would be low, and visibility would be anywhere from three to six miles. Tedder later called Stagg’s presentation “most unpromising.”

No one spoke. Stagg’s gloom had spread to everyone in the room. Admiral Ramsay broke the silence. “Are the Force 5 winds along the Channel to continue on Monday [June 5] and Tuesday?” he asked. “Yes sir,” Stagg replied. Ramsay then asked about the clouds, but Stagg could not give him a definitive answer; they were just too unpredictable. Tedder asked about weather conditions for June 7, to which Stagg predicted that the cold front should push most of the clouds away. Air Marshal Leigh-Mallory, who worried greatly about the airborne forces and his bomber crews, asked about the cloud ceiling. Stagg told him clouds would be down to 500 feet over France, way too low for bomber crews. General Montgomery simply commented, “I’m ready.”

Eisenhower listened to all the questions and answers, gauging the reactions of the questioners. Finally, he addressed Stagg, recounting his forecast from the day before and asking, “Isn’t there just a chance that you might be a bit more optimistic again tomorrow?” Stagg had to tell him no, that the chance he saw previously had disappeared. “The balance has gone too far to the other side for it to swing back again overnight tonight,” he explained. Tedder asked if all the forecasting centers were in consensus about the report, hoping for some dissension. Stagg could not play along. “Yes, sir,” he said. “They are.”

With that information, Eisenhower announced that the invasion would be delayed on a day-to-day basis. Monday, June 5, would no longer be D-Day. But when would the invasion launch, the next day or in two weeks? Eisenhower decided that his final decision would be made in five hours, on June 4. One U.S. naval task force would be allowed to proceed to keep with the timetable and would not be recalled until after the next meeting, if necessary. There were no jokes this time, nothing to lighten the mood. The men filed out of the room with grave looks of worry.

When Montgomery got back to his trailer, he noted in his diary, “Tomorrow the final decision must be taken, and once taken must be stuck to; everything will be at sea, and if it is to be turned back, it must be turned back then. Strong and resolute characters will be very necessary.”

FIFTH MEETING (Sunday, June 4, 4:15 am)

The Sunday meeting convened with some alarming news. An Associated Press teletype operator had been practicing on what she thought was an idle machine that night when she typed out “ASSOCIATED PRESS MYK FLASH—EISENHOWER’S HEADQUARTERS ANNOUNCED ALLIED LANDINGS IN FRANCE.” Unfortunately, the machine was live, and the message traveled across the Atlantic and to Moscow. It was cancelled 30 seconds later but no one knew if the Germans had intercepted it. That little flub by a low-ranking clerk only added to Eisenhower’s stress as he prepared to listen to the latest weather report for the biggest decision of his career.

Tension gripped everyone. Despite the sleepless nights waiting to see if they could launch, most of the officers hoped for an improved forecast. Eisenhower nodded to the serious, unsmiling Stagg who reported almost no changes from his last forecast. The only change: the cold front expected for Wednesday was pushing through faster than expected. It was now expected 24 to 36 hours earlier, but Stagg was not confident it would reach the Channel in time. Everything else—cloud cover, wind direction, and speed—was exactly as previously reported. D-Day would definitely not be on June 5.

Again, Ramsay spoke up first. “The sky outside here at the moment is practically clear and there is no wind,” he explained. “When do we expect the cloud and wind of your forecast to appear here?” Ramsay was ready to launch his fleet if Stagg gave him a window, but Leigh-Mallory interjected before Stagg could answer, explaining that his bombers could not attack through the predicted cloud cover. Bomber crews would have difficulty seeing flares marking their targets, making the bombings less than effective. Tedder agreed with Leigh-Mallory but observed that they had to make the most of the gaps between weather patterns.

Throughout the meeting Eisenhower remained particularly calm and asked fewer questions than before, for good reason. He had a secret he had not told Stagg: A member of Ramsay’s staff had checked with the naval forecasters to get their latest take on the conditions. Ramsay, in turn, had shared the findings with Eisenhower a few minutes before Stagg made his presentation, so Eisenhower was not surprised by the forecast.

Although the sea conditions were calm enough for the Allied ships to cross the Channel, cloud cover would prevent the air forces from completing their mission. Montgomery told Eisenhower he was willing to risk the assault without air support, imploring him, “We must go.” But Tedder disagreed, supporting postponement. Eisenhower agreed with Tedder, explaining that the Germans possessed greater strength in the Normandy area. The operation would only succeed with air superiority. Eisenhower asked if anyone disagreed with his view. No one replied. He then ordered the naval forces that had not yet departed their ports not to sail and the forces that had already sailed to be recalled. Eisenhower scheduled another meeting later in the day.

When the meeting ended, Beetle Smith raced to the communications building and sent the code word for the postponement to all commands. He then called 10 Downing Street, Winston Churchill’s residence, to tell the prime minister the news, and he notified the Combined Chiefs of Staff.

Word was also transmitted to the fleets that the invasion had been delayed and H-hour had been revised. Block and bombardment ships as far away as Belfast, Ireland, turned around and headed to port. But the message failed to reach a convoy of 138 ships headed for Utah Beach. Two destroyers were dispatched to retrieve them but could not find the flotilla. They ended up in a minefield, waiting for minesweepers. Finally, a Supermarine Walrus amphibious aircraft flying out of Portsmouth found the ships and dropped the return order in a canister on the deck of the lead ship. The convoy turned around, but because of the choppy seas one of the Landing Craft Tanks (LCTs) capsized.The crew survived.

SIXTH MEETING (Sunday, June 4, 9:00 pm)

Throughout the day the winds picked up as clouds gathered above the Channel. Men packed aboard ships for more than 72 hours began to feel the strain. By nightfall the rains fell, and the wind blew furiously through the pine trees outside Southwick House.

Inside the meeting room the commanders drank coffee and chatted among themselves. Eisenhower stood tense, the gravity of the decision weighing on him. If he delayed for two weeks it could have a devastating effect on the men’s morale, and if he released them from their vessels they might inadvertently reveal the location of the attack. Even more, Moscow was impatiently awaiting the landings. If he did not launch in the next two days Soviet Premier Josef Stalin might think the Western Allies were not serious about relieving pressure on the Eastern Front. And then there were the Germans. An extra two weeks would give them time to beef up beach defenses and gather more troops. But Eisenhower refused to launch an invasion without a solid chance for success.

Eisenhower called the men to order as Stagg and his staff entered the room. “Gentlemen,” Stagg began as he always did, “since I presented the forecast last evening some rapid and unexpected developments have occurred over the North Atlantic.” He went on to explain that a cold front from one of the depressions had pushed farther south faster than expected. The front would pass over Portsmouth and across the Channel later that night, pushing most of the clouds out. The rain outside would stop in about two or three hours. The remaining clouds would hold at 2,000 to 3,000 feet, and winds would reduce along the French coast to Force 3 or 4. The improved conditions would last from Monday night and into Tuesday. Beyond that the weather would probably be unsettled and hard to predict.

But how long would it last? Stagg’s charts showed that the bad weather and high winds would return by the evening of June 6, and he had no idea how long it would last. Stagg could give Eisenhower only 24 hours of good weather, nothing more. Maj. Gen. Kenneth Strong could not believe it. He looked out the window to see rain pouring down heavily. “I could see no signs that conditions were improving,” he later recalled.

After the usual silence, Admiral Creasy asked about weather improvements from Wednesday, June 7, to Friday, June 9. Stagg put the chances at fair. Eisenhower asked if it was practical to predict the weather beyond Friday. Stagg replied, “Conditions must continue to be regarded as very disturbed.” But he stressed his confidence about the 24-hour forecast, telling the air officers that the clouds would be broken enough for moonlight to shine through the gaps and high enough for good bombing conditions from Monday night to Tuesday afternoon.

Eisenhower had a clear spot in the eye of a storm. The winds would not be south, as he wanted, only southwest. The sky would not be clear, but it would be clear enough. The seas would be satisfactory for the initial assault, but the followup troops might encounter rough conditions. There would be a full moon, but its power would be reduced by intermittent clouds. It was not the ideal situation, but it might be good enough. Eisenhower could risk setting his forces loose, or he could hold up and delay another two weeks and hope for better conditions.

Eisenhower polled the room. Admiral Ramsay reminded him that if D-Day were to be June 6, he would have to give the order to the fleet in the next half hour. If the fleet sailed and the date was delayed again, they would not be able to refuel for a Wednesday assault. That left a two-week wait for ideal conditions. Leigh-Mallory fretted that his bomber crews would not be able to see their bombing markers. Tedder agreed, saying the bomber operations would be “chancy.” Eisenhower then put the question to Montgomery.“Do you see any reason why we should not go on Tuesday?” Without missing a beat the British general announced, “No. I would say go.”

Again, Eisenhower polled the room. Everyone held to their previous concerns. Only Montgomery was confident. Eisenhower then turned to his chief of staff, Smith, who agreed with Montgomery and added that the high seas and moderate winds might trick the Germans into believing the Allies would never attack in such conditions. “It’s a helluva gamble,” Smith told Eisenhower, “but it’s the best possible gamble.”

With all the questions asked, Eisenhower sat silently on the couch for a few minutes while his commander waited on his word. Smith was taken aback by his boss’s huge responsibility. “I never realized before the loneliness and isolation of a commander at a time when such a momentous decision has to be taken, with full knowledge that failure or success rests on his judgment alone.”

Finally, Eisenhower looked up, his face free of tension. “The question is,” Eisenhower said to no one in particular, “just how long can you hang this operation at the end of a limb and let it hang there?” After a short pause he made the decision: “I’m quite positive we must give the order…. I don’t like it but there it is…. I don’t see how we can possibly do anything else.” He asked if there were any dissenting opinions. No one spoke up. D-Day was now set for June 6, but Eisenhower was not completely sold on the new date. He ordered one more meeting in six hours to make sure the weather would cooperate or if the ships and planes would have to be recalled.

SEVENTH MEETING (Monday, June 5, 4:15 am)

The atmosphere of the last meeting was decidedly somber. Sheets of rain beat at the side of Southwick House. Everyone was now in battledress uniform except Field Marshal Montgomery, who wore a light yellow turtleneck and corduroy trousers. The men took their seats with grave faces, and the room quickly grew silent. At least Eisenhower had slept fitfully, having been awakened by gale force winds beating against his trailer. It was a good omen that he had delayed the landings. If he had green-lighted the attack for June 5, the air forces would have been grounded, landing craft would have capsized, and airborne troops would never have reached the battlefield.

Stagg was ushered in. He had heavy bags under his eyes from lack of sleep. “Go ahead Stagg,” Eisenhower ordered. The weather officer delivered a forecast almost identical to the one earlier. He could report this time, however, that the weather from Wednesday to Friday would be variable, with completely overcast skies, clouds at 1,000 feet, and winds up to Force 5 or 6. The conditions, however, would be interspersed with fair periods with Force 4 winds and good visibility.

Everyone felt relieved. The followup operations could go ahead with a decent chance of success. To Stagg, the look on every face “was a joy to behold.” Eisenhower broke into a smile. “Well Stagg,” he beamed, “if this forecast comes off, I promise you we’ll have a celebration when the time comes.” The commanders asked a few questions about how Stagg had come to his conclusions and how far out he was willing to predict.

With everyone’s input delivered, Eisenhower got up and began slowly pacing the floor, his head down and his hands clasped behind his back. Finally, he stopped walking, paused, and turned to the men in the room. With a confident voice he announced, “Go!”

Sidebar: WHAT DID THE GERMANS KNOW?

Twice the Western Allies almost revealed the coming invasion to the Germans on June 4, when a typist accidentally sent out a message claiming Eisenhower had given the order, and when a flotilla of ships almost reached Utah Beach. To make sure they had not tipped their hand, Tedder called Group Captain Frederick Winterbotham to Southwick House.

Winterbotham, a Royal Air Force officer, supervised the distribution of Ultra intercepts to field commanders. Early in the war the British had cracked the German Enigma codes—communications between commanders—and used them to understand what the Germans knew or were intending to do on the battlefields. The deciphering program, known as Ultra, gave the Allies a great edge over Nazi Germany. If anyone knew what the Germans along the coast of Normandy were thinking in the early hours of June 5, it was Winterbotham.

The RAF captain reported to the house and waited at the bottom of the large staircase outside the meeting room as Eisenhower made his final decision. Winterbotham had information vital to the planners that might assist the men preparing to invade France.

Suddenly, the doors burst open and Eisenhower’s commanders charged out. Tedder spotted Winterbotham and nodded at him as he hurried by, saying, “Tomorrow.” Winterbotham, understanding this meant the invasion was on, responded, “Absolutely nothing.” There had been no communication among the Germans that they were bracing for an attack. They had no idea the invasion was coming. In less than 24 hours the first Allied soldiers would drop onto French soil, completely surprising the officers of Germany’s high command in Normandy. The Allies had kept the invasion a secret.

Sidebar: WHAT DID EISENHOWER SAY TO LAUNCH OPERATION OVERLORD?

There are several versions of exactly what General Dwight D. Eisenhower said in giving the “go” order in the early hours of June 5, 1944, to launch the Normandy invasion. Everyone who was in the room when he made the call seemed to hear something different.

Some of the British officers did not recall what Eisenhower said. Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery wrote in his memoir Normandy to the Baltic, “At 0400 hours on 5 June the decision was made: the invasion of France would take place on 6 June.” Air Marshal Arthur Tedder followed suit, simply writing in his memoir, Without Prejudice, “Overlord was launched beyond recall.” Group Captain Stagg, who had left the room prior to Eisenhower’s decision and was outside in the hall, later wrote in Forecast for Overlord, “General Eisenhower had made the final and irrevocable decision.”

Two British officers who did quote Eisenhower wrote completely different versions of the order. In his memoir, Intelligence at the Top, Maj. Gen. Kenneth Strong heard Eisenhower say, “Okay boys, we will go.” Major General Frederick de Guingand, however, gave Eisenhower a bit of a soliloquy in his memoir Operation Victory. According to de Guingand, Eisenhower came forward after everyone had expressed their opinions. “This is a decision which I must make alone,” de Guingand claimed Eisenhower said. “After all, that is what I am here for.” Then, as everyone waited, Eisenhower gave the order: “We set sail tomorrow.”

The one American in the room who later wrote about the meeting also heard something different. In his book, Eisenhower’s Six Great Decisions: Europe, 1944-1945, Lt. Gen. Beetle Smith claimed that Eisenhower gave the order, “Well, we’ll go.”

U.S. Army Historian Forrest Pogue tried to settle the matter for the Army’s official history of World War II. He collected statements from several participants and accessed reports written hours, days and years after the meeting. No two versions were the same. Finally, for his book, The Supreme Command, Pogue simply quoted Eisenhower as saying “Go.” Historian Stephen Ambrose also tried to solve the quote mystery, which he eventually wrote about in his biography, The Supreme Commander. Ambrose claimed that when he interviewed Eisenhower on October 27, 1967, Eisenhower told him that he was sure he said, “O.K., let’s go,” but Ambrose’s meetings with Eisenhower have lately come under question.

Eisenhower tried to settle the matter himself when he told reporter Walter Cronkite in a 1963 interview that he said, “Okay, we’ll go.” But the controversy was not over. In 2014, Tim Rives, the supervisory archivist and deputy director of the Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum in Abilene, Kansas, researched the controversy and found that Eisenhower wrote five different versions of his own quote while editing an article he wrote for Paris Match. The only conclusion could be that Eisenhower himself did not remember exactly what he said and, therefore, his words are forever lost to history.

Kevin M. Hymel is the historian for the U.S. Air Force Chaplain Corps. He is the author of Patton’s Photographs: War as He Saw It, and leads battlefield tours for Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours, which include Southwick House.

Very interesting , enjoyed reading that