By Michael D. Hull

After the German Army’s invasion of Russia in June 1941 and the capture of the historic Lithuanian city of Vilnius late that month, Abba Kovner and a group of friends took refuge in a Dominican convent on the city’s outskirts.

Born in Sevastopol, Russia, Kovner had attended a Hebrew secondary school in Vilnius, a center of Jewish culture known as the “Jerusalem of Lithuania.” When he learned that the Germans were murdering Lithuanian Jews, Kovner, then aged 23, quickly formed a group of Jewish partisans.

“One of the Biggest Jewish Slaughterhouses in Europe”

Repeated short bursts of gunfire were heard coming from the village of Ponary, eight kilometers south of Vilnius. “Sometimes they would go on for hours, or sometimes it would be rounds of machine-gun fire,” reported Jozef Mackiewicz, a Polish writer who lived in Vilnius. “This happened on different days, almost always in broad daylight. Sometimes on several days in a row, usually near dusk or morning.”

Mackiewicz knew that mass slaughter was occurring, and he concluded that Ponary was “one of the biggest Jewish slaughterhouses in Europe.” It was said that all Gestapo roads led to Ponary.

When Wehrmacht troops seized Vilnius on June 24, 1941, two days after the massive Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, they found about 57,000 Jews living in the city—a third of the population. Six months later, there would be only 20,000 left. The killings in Lithuania were carried out by so-called action groups of Einsatzkommando 3, led by SS Colonel Karl Jager and supported by Lithuanian troops, from July 2, 1941, onward. Einsatzgruppen were mobile killing squads responsible for carrying out the liquidation of non-Aryan peoples considered inferior by the Nazis in the occupied countries. The brutality of the Lithuanian troops toward the Jews matched that of the Nazis. Of the 57,000 Jews in Vilnius, only 16,500 were still alive by the beginning of December 1941. In six months, an estimated 38,000 Jews were exterminated while another 5,000 fled into the forests. By the end of 1941, more than half a million Jews had been slaughtered in the Baltic, White Russia, eastern Poland, and the Ukraine.

Colonel Jager reported to his superiors on December 1, “Today I can confirm that our objective to solve the Jewish problem for Lithuania has been achieved by EK 3. In Lithuania there are no more Jews, apart from Jewish workers and their families…. I consider the Jewish action more or less terminated as far as Einsatzkommando 3 is concerned. Those working Jews and Jewesses still available are needed urgently, and I can envisage that after the winter, this workforce will be required even more urgently.

“I am of the view that the sterilization program of the male worker Jews should be started immediately so that reproduction is prevented. If, despite sterilization, a Jewess becomes pregnant, she will be liquidated.”

“Let Us Not Go Like Sheep to the Slaughter”

Kovner, who would later become a well-known poet in the new state of Israel after the war, recognized earlier than his friends that the massacres by the SS Einsatzgruppen were part of the systematic Nazi extermination plan—the so-called “Final Solution of the Jewish Question”—to rid Europe of Jews and other non-Aryans, and he was the first to call for armed resistance. On December 31, 1941, as a resistance group commander, he read aloud a manifesto in one of the partisan camps: “Hitler plans to kill all the Jews of Europe. The Jews of Lithuania are the first in line. Let us not go like sheep to the slaughter. We may be weak and defenseless, but the only possible answer to the enemy is resistance!” Critical of the older generations of Jews who had submitted meekly to the Nazis without a struggle, Kovner and his young comrades agreed, “It is better to die fighting like free men than to live at the mercy of the murderers.”

On September 6, 1941, the remaining Jewish population of Vilnius had been herded into two ghettos. Those considered capable of work or possessing useful skills were sent to one ghetto, and the rest to the other. The two groups were issued different identity cards. After a series of “selections” was made in the second ghetto, the victims were taken by truck or train to a wooded area beside the railroad tracks in Ponary. There, they were shot.

An Electrician by Trade

Meanwhile, a large number of Jews from the first ghetto in Vilnius were put to work by the German occupiers. Near the city’s main railroad station was a camp where German Army replacements and stragglers awaited reassignment to new units. In the camp there were upholstering, tailoring, locksmithing, and shoe-mending workshops, and the Jews were assigned to labor duties in them.

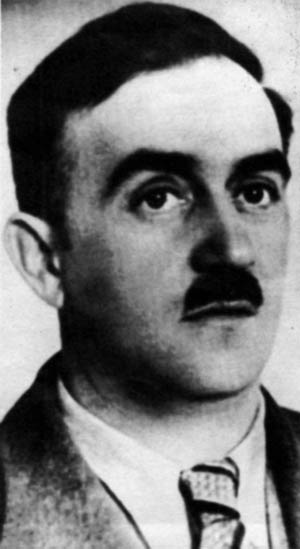

In charge of the camp was an obscure yet remarkable man, quite unlike his hard, ruthless Wehrmacht comrades. He was mild, mustached feldwebel (Sergeant) Anton Schmid of Company 2 of Landeschutzen-Bataillon 898. Born in modest circumstances on January 9, 1900, in Vienna, where his father was a postal worker, Schmid was trained as an electrician. He was drafted into the Austrian Army in July 1918, the last year of World War I, but was granted permanent leave a few months later.

He married a young woman named Stephanie, and they had a daughter, Grete. In 1928, Schmid opened a small radio and electrical appliance store in Vienna. After the German annexation of Austria in 1938, Schmid, a devout Roman Catholic sensitive to the sufferings of others, helped several Viennese Jews escape from Nazism to Czechoslovakia. In 1939, when World War II broke out, he received another draft notice, this time from Adolf Hitler’s Wehrmacht.

But Schmid was almost 40 years old, so he was not sent to the front lines. He regarded himself not as a career soldier, but as “a civilian in uniform.” After bidding farewell to his wife and daughter, he was assigned to German Army support units in rear areas, first in Poland and later in the Soviet Union after the German invasion on June 22, 1941. By now a sergeant, Schmid arrived in Vilnius in the autumn of 1941.

Supporting the Partisans

Founded in the 10th century and made the capital of Lithuania in 1323, Vilnius is a commercial city with a railroad junction, industrial plants, and a dozen 17th-century churches. It is the seat of Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox archbishoprics. Confirmed as Polish by the League of Nations in 1923, Vilnius was restored to Lithuania in 1939 and occupied by Soviet troops that year.

Schmid was shocked by what he learned of the mass killings in Ponary and was moved by the plight of the Jews in the Vilnius ghetto. He decided to secretly assist them. In a letter to his wife, he wrote, “You know how it is with my soft heart. I could not think, and had to help them.”

He befriended a number of the Jewish partisans and the laborers in his workshops, including Kovner and writer Hermann Adler and his wife, Anita. Kovner expressed amazement at meeting a soldier in the German Army who was willing to aid Jews. Schmid hid the Adlers in the Wehrmacht building where he worked, and they acted as go-betweens, enabling the German sergeant to cooperate with the Jewish underground. Adler later testified to Schmid’s heroic rescue efforts.

The former Vienna electrician quickly gained the affection and confidence of the Jews, and, at great personal risk, slipped regularly into the ghetto. He smuggled food to starving families and carried bottles of milk in his pockets to give to mothers for their babies. He knew that thousands of Jews were hiding elsewhere in the Vilnius area and acted as a courier between them and their friends in the ghetto.

He carried bread, messages, and what drugs he could find, and even dared to steal German weapons for the resistance fighters. As Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal reported later, the mild sergeant became “a secret one-man relief organization.” A survivor told Wiesenthal, “He did it out of the goodness of his heart. To us in the ghetto, the frail, quiet man in his feldwebel’s uniform was a sort of saint.” Schmid never took any payment for his clandestine efforts.

A writer named Purpur, whom Schmid hid in his living quarters, asked him one day, “Isn’t it reckless, risking your life like this?” Schmid replied, “We’re all going to croak sometime. But if I get to choose between croaking as someone who killed people or someone who helped them, then I’d rather go out as a helper.”

350 Lives Saved

The sergeant aided the Jews for several tense months, from October 1941 to February 1942. He concealed many in the cellars of three houses in Vilnius that were under his supervision, often keeping more than 20 overnight at a time. Some of the Jewish partisans slept in Schmid’s home and planned their activities there.

He saved the lives of 350 Jews by issuing them false yellow identification cards that indicated they were skilled in trades useful to the German occupiers. He also maintained contacts with members of the Jewish underground that was preparing for an uprising in the infamous Warsaw ghetto. He managed to release Jewish captives capable of work from the notorious Lakishki Prison and cooperated with leading figures in the underground, such as the colorful, audacious Mordecai Tenenbaum, who led Jewish resistance fighters in the northeastern Polish city of Bialystok. Schmid also sent Jews to ghettos that were more secure at the time—in Voronovo, Lida, and Grodno.

Hermann Adler reported that Schmid, with the aid of some German comrades he could trust, drove groups of Jews over long distances in his truck to Warsaw, where he was officially supposed to deliver German soldiers who had become separated from their units.

But it was only a matter of time before Sergeant Schmid’s superiors were alerted to his humanitarian activities. The Gestapo became aware of the presence of many Jews from Vilnius in the Lida ghetto, and when some of them were arrested and tortured they revealed that they had arrived there with the sergeant’s assistance. Schmid was speedily tried by the war court of the office of the Vilnius field commander and was sentenced to death on February 25, 1942.

The court files and judgment did not survive the war, but the formal charge was accepting bribes and also probably involved providing aid and comfort to the “enemy.” Stephanie Schmid in Vienna was notified of the death sentence. She demanded information from the court but was fobbed off with formalities.

Last Letter Home

After the sentencing, Schmid wrote a poignant farewell letter to his beloved wife and daughter: “I must tell you what fate awaits me, but please, be strong when you read on…. I have just been sentenced to death by a court-martial. There is nothing one can do except appeal for mercy, which I’ve done. It won’t be decided until noon, but I believe it will be turned down. But, my dears, cheer up. I am resigned to my fate. It has been decided from Above—by our dear Lord—and nothing can be done about it.

“I am so quiet that I can hardly believe it myself. Our dear God willed it that way, and He made me strong. I hope He will give you strength, too. I must tell you how it happened. There were so many Jews here who were driven together by the Lithuanian soldiers and were shot in a meadow outside the city—from 2,000 to 3,000 people at one time. They always picked up the small children and smashed their heads against trees—can you imagine that?

“I had orders (though I didn’t like it) to take over the soldiers’ retrieval unit … where 140 Jews worked. They asked me to get them away from here. I let myself be persuaded—you know I have a soft heart. I couldn’t think it over. I helped them, which was very bad, according to my judges. It will be hard for you … but forgive me: I acted as a human being, and didn’t want to hurt anyone. When you read this letter, I will no longer be on this earth. I won’t be able to write you anymore. But be sure that we shall meet again in a better world with our Lord.”

Sergeant Schmid was executed by a firing squad on Monday, April 13, 1942, shortly after penning one more letter to his wife: “My dear Steffi. I could not change anything, otherwise I would have spared you and Grete all this. All I did was to save people, who were admittedly Jews, from the fate that now awaits me, and that was my death. Just as in life I gave up everything for others…. Now I close my last lines, the last I can write to you, and send you my love.

“I kiss you both, and another kiss to you, Steffi, you are everything to me in this world and the next, where soon I will be in God’s hand. Many kisses, love forever from your Toni.” Anton Schmid was buried at the German military cemetery in the Anatol district of Vilnius.

Sergeant Schmid’s Sacrifice Comes to Light

The first public recognition of Anton Schmid’s sacrifice came in 1945 when Hermann Adler, who owed his life to him, published a volume of poetry, Songs from the City of Death. In the preface, he wrote, “I remember also an obscure sergeant from Vienna, Anton Schmid, who was sentenced to death by firing squad by a German military court because he saved those who were being persecuted, and who now rests under a simple wooden cross at the edge of the German soldiers’ cemetery in Vilna [Vilnius].”

Although Adler’s poems, written mostly in the Vilnius ghetto, received a prize from the literature commission of the city of Zurich, Switzerland, the saga of Sergeant Schmid did not enter the public consciousness in Germany for many years. The same held true of another book of poems by Adler, entitled Ostra Brama (the name of a church in Vilnius), in the eighth section of which he commemorated Schmid under the title, “A Friend’s Sure Hand.”

Eventually, Germans began to come to grips with the facts of their history during World War II—the bloody trampling of neutral nations, the enslavement of millions, the widespread genocide, and also the deeds of heroes who had resisted Nazi tyranny. In the 1960s, Adler was commissioned to write scripts about the tragic sergeant for a German television documentary and a radio program. Israel honored Schmid in 1967 as a “righteous Gentile” for sacrificing his life during the World War II genocide. A tree dedicated to him was planted on the grounds of the Yad Vashem memorial garden in Jerusalem, accompanied by an inconspicuous stone tablet inscribed “Anton Schmid—Austria.” His widow was awarded a “Righteous Among the Nations” medal bearing the inscription, “Whoever saves one life—saves the world entire.”

Nazi hunter Wiesenthal interviewed people who had been rescued by the gentle sergeant from Vienna and concluded, “Schmid was not the drill-sergeant type. He was a quiet man who did a lot of thinking and said very little; he had few friends among his army buddies.” Of the only known portrait of Schmid, Wiesenthal observed, “It shows a thoughtful face, with soft, sad eyes, dark hair, and a small mustache.” He was, said Wiesenthal, “a devout Catholic who suffered deeply when he saw other people suffer. He was a man of exceptional courage.”

Finally, almost six decades after his heroic actions, Anton Schmid received official recognition in Germany. On May 8, 2000, the 55th anniversary of the end of the war in Europe, the German Army base in the Schleswig-Holstein town of Rendsburg, which had been named for General Gunther Rudel, a veteran of both world wars, was renamed Feldwebel Anton Schmid Kaserne. At the dedication ceremony, Defense Minister Rudolf Scharping declared, “We are not free to choose our history, but we can choose the examples we take from that history. Too many bowed to the threats and temptations of the dictator, and too few found the strength to resist. But Sergeant Anton Schmid did resist….”

Thanks so much for this article. We need to know the stories the public schools won’t tell.