By Kevin Hymel

The mission was simple: “There’s fire along that hedgerow there. Take care of it.”

The order went to First Lieutenant Richard “Dick” Winters, the acting commander of Easy Company, 2nd Battalion, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division. The order came from the battalion’s operations officer, Captain Clarence Hester, who, with a sweep of his hand, showed Winters the area he was to attack. The sound of the enemy fire was close and unmistakable. German artillery was raining fire down on Utah Beach, the westernmost invasion beach along the Normandy coast, where at that very moment American soldiers from the 4th Infantry Division were struggling ashore. It was the 8:30 in the morning of D-Day––June 6, 1944.

The mission should have gone to Easy Company’s commander, First Lieutenant Thomas Meehan III, but he was nowhere to be found. (It was later learned that Meehan, along with an entire stick of 18 paratroopers, died when their C-47 “Skytrain” transport plane, chalk #66, was hit by antiaircraft fire and crashed near Beuzeville-au-Plain, France.) Winters, Easy’s 1st Platoon commander, became the acting commander by default.

Winters, like every paratrooper around him, had jumped into Normandy some seven hours earlier and had had most of his equipment ripped off his body during the violent exit from his C-47. Fortunately, he had picked up a discarded M-1 rifle and a few grenades during his trek to the small town of Le Grand Chemin, where the battalion had set up temporary headquarters.

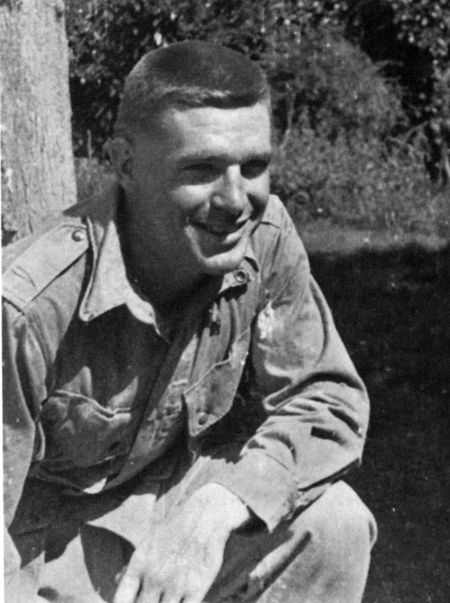

Winters could count only 11 Easy Company men from a unit that normally numbered nearly 200. With him were Lieutenant Lynn “Buck” Compton, Staff Sergeant Carwood Lipton, Staff Sergeant Bill Guarnere, Sergeants Don Malarkey and Myron Ranney, Corporals Joseph Liebgott, John Plesha, and Joe Toye, and Privates Walter Hendrix, Robert “Popeye” Wynn, and Cleveland Petty.

Fortunately, Winters was also able to gather a few more volunteers from other 506th units who had been misdropped during the chaotic aerial assault; Privates John Hall of Alpha Company, Gerald Lorraine, and Virgil “Red” Kimberling of Headquarters Company agreed to join the attack. Then Private Walter Hicks from Fox Company showed up and offered to help. “Hicks,” Winters said, “see if anyone else from F Company wants to go along.” Hicks brought back Sergeant Julius “Rusty” Houck. Winters now had 17 men, including himself.

Winters had one wild card in his group. Bill Guarnere had learned before the jump that his brother had been killed in Italy. He was not only angry and wanting to kill every German, but he did not trust Winters. “I respected Winters as an officer,” Guarnere later wrote, “but no one proved themselves in combat yet.” Earlier that morning, when the men had encountered a horse-drawn supply train, Guarnere had let loose, slaughtering men and animals. “I had so much anger I might have turned around and shot him [Winters] if he had tried to stop me.”

Winters gathered his team along a road just outside the village of Le Grand Chemin, about five miles inland. “Just weapons and ammo,” Winters told the men. “Leave everything else here.” Sergeant Lipton instinctively dropped his musette bag, which held some blocks of TNT and percussion caps. He would later regret it.

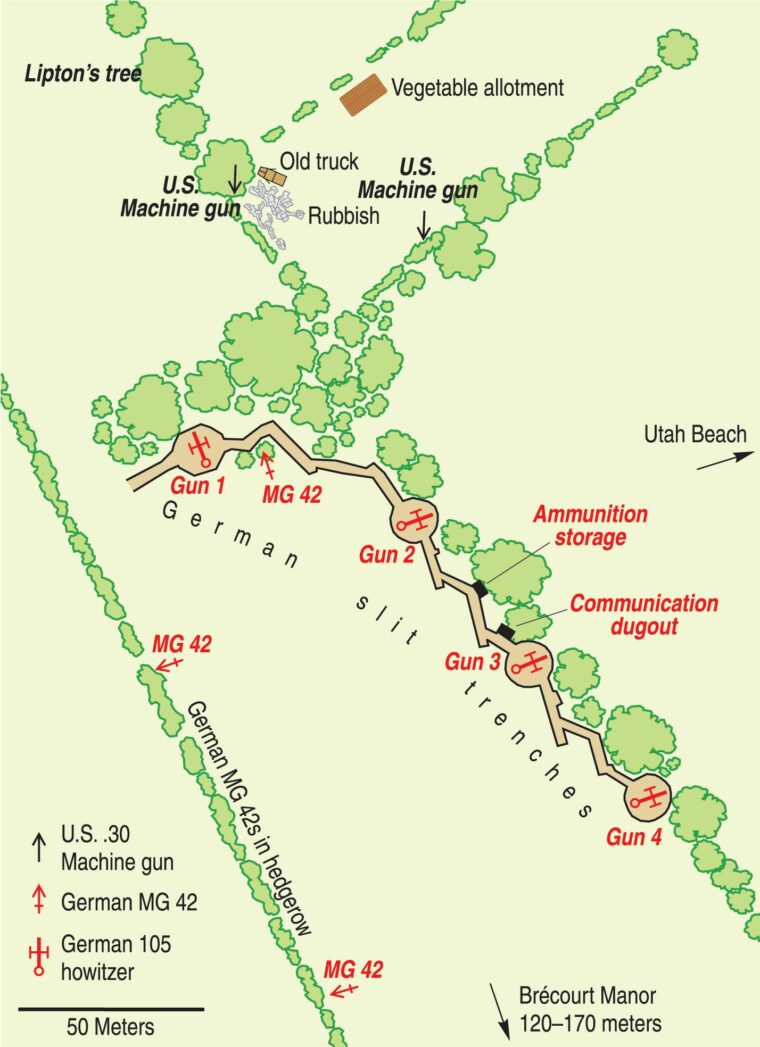

Winters led his small force across a field toward the guns, crawling ahead of them along a hedgerow, until he could get a view of the enemy battery. He saw four 105mm artillery pieces firing from a trench, dug in behind a hedgerow. Three guns faced east and one faced north, protecting the battery’s left flank. The position resembled an L-shape with zigzagging trenches connecting each gun pit.

The field itself was surrounded by hedgerows—thick earthen walls cluttered with trees and overgrowth—as tough and as impenetrable as a stone fortress. Behind the 105s, at the opposite side of the field, a few machine-gun nests protected the battery’s rear. At the far end of the field, opposite the approach of Winters’s force, ran a small country road, on the other side of which stood a barn and a house—Brécourt Manor.

Winters did not know it, but his troops were up against approximately 50 enemy soldiers from the 6th Battery of the 90th German Regimental Artillery. The locals considered the young German gunners to be fanatic Nazis. Earlier that day German Lt. Col. Friedrich von der Heydte, an experienced paratrooper and commander of the 6th Fallschirmjäger Regiment, had climbed the church tower at nearby Sainte Marie du Mont and saw the Allied invasion fleet off Utah Beach. He rushed to the 6th Battery at 8 am and immediately ordered the weapons manned and firing. By the time Winters had received his orders, the gunners at Brécourt Manor had already repulsed one probing attack from elements of the 506th.

Winters devised a simple but direct strategy following the principle of fire and maneuver: he would attack the first gun by laying down machine-gun fire while his assault force made its way across an open field. Right on their heels would be a secondary force that would spike the guns. Once the first gun was taken, the men would then work their way down the trench to each consecutive gun, knocking it out until the battery was silenced.

The First Gun

Winters placed one .30-caliber machine gun, manned by Petty and Liebgott, in a position that allowed his assault team to get into place. He then divided his men into two teams and led them closer to the big guns. He placed another machine gun, manned by Plesha and Hendrix, along a hedge directly facing the first gun, warning the men not to fire unless they had a direct target—they were too exposed. He then ordered Lipton and Ranney to work their way along the hedgerow to their right and provide flank protection.

As Winters and the men crawled across the field to the battery’s trenches, Winters noticed a bobbing German helmet. He fired two shots and the helmet dropped below the parapet of the trench. He then ordered Malarkey to lead the assault.

Malarkey recalled that he “took a deep breath and, carbine in front of me, started snaking my way forward on elbows and knees, rifle poised, staying low in the foot-high Normandy grass.”

Suddenly, Winters realized that Malarkey had only grenades and was out of carbine ammunition. He shouted, “Wait, Malark, get back here!” Malarkey returned and Winters told him to get more ammo while he ordered Compton forward. “[Winters] probably saved my life,” recalled Malarkey, “which wouldn’t be the last time.”

Compton, armed with a borrowed Thompson he had never fired before, crawled through the grass while Winters and the others provided covering fire. Compton climbed over a hedgerow and eyed two Germans loading and firing one of the artillery pieces toward the 4th Infantry Division coming ashore at Utah Beach.

Although he was only supposed to observe, Compton jumped from the hedgerow into the trench and charged the Germans. About halfway down the trench he planted himself and raised his Thompson sub-machine gun to his waist, “like Jimmy Cagney in a gangster movie,” he later recalled. The Germans spun around and gaped in horror at their uninvited visitor. Compton pulled the trigger but nothing happened, except for a slight “plunk” sound from the weapon—the firing pin had broken.

“I looked at the Germans. They looked at me in surprise. There were two of them and one of me. They were armed to the hilt. I wasn’t,” Compton said.

As the three men stood staring at each other, Guarnere ran up beside Compton and opened fire with his Thompson. One German crumpled and the other jumped out of the trench and took off across the field. Compton, a former college baseball star with aspirations of making the major leagues, yanked out a grenade and hurled it at him. It exploded right above the man’s head, killing him instantly.

Bill Guarnere recalled, “The Germans ran like hell down the trench in the other direction. Winters and the other guys were right behind us, and all of us started lobbing grenades and shooting everything we had. Tossing grenades and attacking, it was stupid, but we did it so quick, so fast, they thought an entire company was attacking. We caught them with their pants down.”

Compton then waved the rest of the team forward. They piled into the trench and continued lobbing grenades at the other Germans. The first 105 was now in American hands.

Meanwhile, Lipton and Ranney had arrived at their flanking position but realized they could not spot the Germans through the heavy undergrowth. Hearing the assault, they quickly climbed two trees. The trees were small and weak, forcing Lipton to carefully balance himself on a branch close to the trunk. From his ringside seat, he could see Germans in both prepared positions and lying prone in the field, firing on Winters’s assault force. None of them had yet spotted him or Ranney.

Lipton fired two shots at one of the prone Germans, but the man seemed to simply duck down. Lipton then fired at a dirt mound to check the sighting on his rifle. The dirt exploded exactly where he aimed. Knowing that his first two shots had hit their target, he then opened up on the Germans.

The Second Gun

Back at the first gun, a German grenade exploded in Popeye Wynn’s trench, hitting him in the buttocks. “I’m sorry lieutenant,” he called to Winters, “I goofed, I goofed! I’m sorry!” The men barely had time to help him out. They had the Germans on the run and did not want to let up, lest the enemy realize how small a force they were fighting.

A German “potato-masher” stick grenade landed in the trench near the Americans and everyone dove forward as it landed between Joe Toye’s legs. “Joe!” hollered Winters, “Move for Christ’s sake, move!” and Toye flipped over and scrambled to run. The grenade exploded, but the stock of Toye’s rifle caught most of the blast; Toye received only some wooden splinters and was able to continue the fight. Guarnere noted, “He was lucky; the rifle took the brunt of it. Otherwise he’d be singing soprano.”

The team then resumed firing down the trench at the Germans, three of whom leapt out and fled across the field, offering perfect targets. Winters hollered for Lorraine and Guarnere, who were standing close by. All three opened fire. Winters hit his man in the head and Lorraine caught his man with a blast from his Thompson. Guarnere, so full of adrenaline and rage, missed his target. “I never missed!” he thought angrily. “Never missed!”

Guarnere’s German switched directions and headed toward one of the guns. He had only taken two steps when Winters drilled him in the back. Guarnere calmed down enough to pump the wounded German full of lead. Then a fourth enemy soldier popped up about 100 yards away and began running. Winters assumed a prone position, took a steady bead on the man, and felled him with one shot. “This entire engagement must have taken about 15 or 20 seconds since we had rushed the initial gun position,” Winters later noted.

Malarkey, meanwhile, noticed two Germans down the trench setting up a machine gun but, as he threw a grenade, Winters also opened fire on them, hitting one man in the hip, the other in the shoulder. Malarkey then climbed out of the trench and, spraying the area with his Thompson, headed toward the second 105. The Germans were fleeing as he slid next to a dead German under the gun. He noticed another dead German in the field, with a case on his hip, which he assumed held a Luger pistol. He bolted for the German to grab a souvenir. “Malarkey, you idiot!” Winters shouted. “Get back here!”

But it was too late. Malarkey reached the dead German and grabbed for the case, which turned out to hold only an artillery-sighting device. “Damn!” was his only thought. The Germans, who had held their fire during Malarkey’s dash, now began blazing away at him. He charged back to the safety of the 105 as bullets kicked up dirt around his feet, “like a late-spring hailstorm back in Oregon,” he later recalled. As he dove into the gun pit, his helmet fell off. He lay on his back, panting while bullets smacked into the gun above him, dropping burning fragments onto his face.

As Malarkey rolled over, he heard Guarnere call to him: “Malark, we’ll time the bursts.” Guarnere was in the trench about five feet from him. So Malarkey and Guarnere began counting the dead time between the enemy’s machine-gun bursts. “Okay,” called Guarnere, “next burst ends, get your ass over here.” Silence, then Guarnere shouted, “Now!” Malarkey bolted and made it to cover. “Way to go,” Guarnere congratulated him, “you stupid mick!”

Meanwhile, Winters prepared the men for the assault on the second gun, ordering Compton and Toye to provide covering fire. Winters then backtracked down the trench where he came across Wynn, lying on the ground and continuing to apologize for being shot. Winters ordered him to make his way back to battalion headquarters alone since he could not spare a man to assist him. The loss of Wynne was soon made up for when Lieutenant Bob Brewer, one of Easy Company’s assistant platoon commanders, joined the assault force. German fire was increasing.

Compton noted that he and Brewer “spotted an empty gun emplacement, maybe 12 feet in diameter, and jumped in, bullets still streaming over us.”

They saw a large ammunition box with a German grenade lying on top of it; somebody bumped the box. The grenade rolled off and the pin fell out. Compton yelled “Look out!” but there was little they could do but brace themselves against the embankments. The grenade exploded. When the smoke cleared, everyone was covered in dirt but no one was hurt.

The explosion was enough to scare one German into surrendering. He ran toward the Americans with his hands raised, crying. One of the Americans––“a desk jockey from headquarters,” as Compton put it—belted the new prisoner in the mouth using a pair of brass knuckles built into the handle of his trench knife. The German began bleeding and spitting out teeth. “Probably broke his jaw,” Compton said. “It was senseless. The prisoner wasn’t offering us any resistance.” Compton grabbed the trooper by the arm and spun him around. “I gave our guy hell for doing it. Malarkey says I threatened the guy with a court-martial, but I don’t remember that. I was too mad.” Compton told him “to get his ass out of there. We didn’t need his crap.”

While this was going on in the trenches, Lipton and Ranney, in their tree perches, started receiving fire. Lipton had managed to get off between 20 and 30 rounds before the Germans finally realized they were getting hit from above. Some turned left and opened fire on the two exposed troopers. “Bullets were clipping branches and cracking all around me as I scrambled down,” recalled Lipton. He made it to the ground without a scratch.

Lipton then hurried over to the other men, coming across Popeye Wynn on his way. He sprinkled some sulfa powder into Wynn’s wound, bandaged it, then dragged him to a farm cart. Once Lipton reached the first gun position, Winters told him they had nothing with which to disable the 105––nor any of the other guns for that matter. Remembering the TNT in his musette bag, Lipton crawled back toward Le Grand Chemin and retrieved it.

On his return trip, he came across a group of American officers and men, all headed in his direction. The officer ahead of Lipton turned back and asked him where he could find the headquarters. Lipton looked at the man behind him, Warrant Officer J.G. Andrew Hill, who started to answer, but before he could say a word, a bullet struck Hill in the forehead, killing him instantly.

Back at the first gun, the German who had been hit with the brass knuckles continued to moan and groan. Winters finally went over to him and kicked him in the pants, ordering him to walk in the direction of battalion headquarters. Just as the man got up to leave, Winters noticed three Germans inexplicably walking casually toward his location. He directed two of his men to set the range of their rifles to about 200 yards. When the Germans stopped and seemed to listen to something, Winters called out, “ready … aim….”

Suddenly Lorraine opened up with his Thompson, which Winters thought “isn’t worth a damn over fifty-to-seventy yards.” One of the Germans went down, wounded, but the German machine guns quickly responded, tearing across the top of Winters’s trench. An opportunity had been wasted.

Winters did not intend to waste another on the second gun. Realizing that German machine-gun fire had slackened as they got closer to the first gun position, Winters deduced that by charging the second gun, with good covering fire, his men would not be exposed to as much enemy fire. He ordered three men to remain at the first gun to supply the covering fire, then, like a coiled spring, the rest of the men charged the second gun, throwing grenades and yelling along the way. The men quickly captured the second 105.

The Third Gun

With two guns captured and two to go, Winters sent a runner back to battalion headquarters for more ammunition and men. He also noticed that Petty, who had been manning one of the machine guns between the first and second 105s, had been hit in the neck. Winters ordered Malarkey to take over the weapon.

The Germans, meanwhile, were trying to wrest the high ground from the Americans. A German officer, rifle in hand, approached the manor house and asked the owner if he could use the second story as a sniper’s nest. Mr. Charles DeVallavieille, a retired colonel who had fought in World War I, refused. He lied and said the house did not have any windows. The German did not protest and left. For the rest of the battle, the house was never occupied by the Germans, save for two wounded men. Only a few Germans retreated through the yard. Altogether, eight civilians occupied the house, including a two-month-old baby, but none were injured in the battle.

After about a half hour, two machine-gun crews arrived from battalion. Winters put them in place for the assault on the third gun. This attack was a little different. With ammunition running dangerously low, there would be no more random fire. Instead each trooper picked his targets and made sure every shot counted. The men charged the weapon.

Compton later wrote in his memoirs, “A big tall kid [Pfc. John Hall] came down the trench and ran by me. He had served as a waiter in the officers’ mess, where I knew him, but he wasn’t in my platoon and I didn’t know his name. From the trench, I saw him spin around and sprint back toward me. He took a bullet in the back and collapsed in front of me, dead.”

Again, nobody had time to stop for the dead or wounded; mourning would have to wait. The rest of Winters’s men bolted forward and quickly captured the third gun.

The Fourth Gun

For a second time, a few Germans ran forward with their hands over their heads, calling out, “No make me dead!” Winters counted six in all and sent them back to headquarters with an escort, along with a request for more ammunition and men.

Concerned about a flank attack, Winters ordered Malarkey to take up a position back where they had first launched the attack and guard the area. “It was a lonely job,” Malarkey confessed. He would remain there for the rest of the battle, hurling grenades and firing at any Germans he saw.

Captain Hester showed up in the trenches and gave Winters three blocks of TNT and an incendiary grenade to spike the captured 105s. He also told Winters that Lieutenant Ronald Speirs from Dog Company would soon arrive with a five-man reinforcement team. Winters used the waiting time to destroy the guns and gather any intelligence. He spiked the first gun himself by dropping one block of TNT down its barrel. To detonate it, someone else pulled the fuse on a German potato-masher and slipped it down the barrel. The mix exploded inside the weapon; it would never fire again. For the second and third guns, he gave the rest of the TNT to Hicks and Kimberling, who also dropped some grenades down the barrels, disabling them.

At gun number two, Winters discovered a German map that marked out every battery along the entire coast and their fields of fire. He also noticed something odd: belts of wood-tipped ammunition. “Were the Germans that desperate for lead?” he wondered.

Speirs finally arrived with his reinforcements, including Privates Art “Jumbo” DiMarzio, and Ray Taylor. Once Winters briefed Speirs, the fresh officer charged the last gun, blazing away with his Thompson as he ran.

Seeing Speirs tear off toward the enemy, one of the men said in amazement, “Look at that crazy mother—go!!”Right on Speirs’ heels charged Bill Guarnere. “I was so hyped up,” recalled Guarnere, “I followed right behind him.” Behind Guarnere ran the other Dog Company men and the two Fox Company troopers, Hicks and Houch.

As the men ran down the trench, Houch rose to throw a grenade, but just as he released it, a burst of automatic-weapons fire stitched his back and shoulders, killing him. Hicks was struck in the shin with a bullet that mushroomed when it hit and tore up his calf. “I think I slowed one down,” he told the trooper who bandaged his wound. (Hicks claimed that Compton bandaged his leg, but Compton has no recollection of it. Lieutenant Brewer may have been the one to bandage Hicks’s leg.)

The fury of Speirs’s attack scared the Germans right out of the last gun pit. They jumped out and began to run just as Speirs leapt in, feet first. He opened up on the fleeing Germans until an enemy grenade exploded near him. The last gun was finally in American hands; the landings at Utah Beach would not be bothered by this battery.

As the firing abated, Guarnere picked up a pair of German binoculars and was using them to examine the German machine-gun positions when he suddenly collapsed. Joe Toye spotted him and, thinking his friend was dead, smacked him on the back of the helmet. Guarnere jumped. “He scared the hell out of me and I scared the hell out of him,” remembered Guarnere. With his adrenaline spent and the mission completed, Guarnere had simply fallen asleep.

End of the Battle

The mission at last complete, Winters ordered the men to make their way back to headquarters at Le Grand Chemin. He pulled out the machine gunners first, followed by the riflemen. Guarnere spotted Malarkey at his lonely post and called to him, “Malark, pull back to the trench.” Malarkey followed, dropping a fragmentation grenade down the tube of the first 105 for good measure as he went.

To cover the withdrawal, Malarkey manned a 60mm mortar while Toye and Guarnere fired .30 caliber machine guns across the field. They blasted the hedgerows along the street near the fourth gun. Malarkey fired so many rounds he buried his mortar in the ground. He had lost his base plate during his jump and was forced to bore-sight his weapon. His firing shattered every window in the manor house, but did not harm any of the civilians inside.

As Winters withdrew, he noticed a wounded German who was trying to operate his machine gun. Winters raised his rifle and blew a hole in the man’s head.

As he made his way back to headquarters, Winters came across the body of Warrant Officer Hill, who lay dead with his right arm sticking straight up in the air, his watch exposed. As machine-gun rounds whizzed overhead, Winters crawled past him, then turned around and reached up Hill’s wrist to pull off his watch. “You are nuts,” Winters thought to himself. “This watch isn’t worth it.”

The big guns of Brécourt Manor were silenced but several German machine-gun positions remained, capable of troubling any unlucky American who passed by. Winters wanted to clean out the entire position but he didn’t have enough men. After refreshing himself with a swig of hard cider, he found about 30 Easy Company men, led by Lieutenants Harry Welsh and Warren Roush, who had been scattered far and wide during the drop.

In addition, Lieutenant Lewis Nixon, the battalion’s intelligence officer, soon arrived, riding the lead on two tanks that had just clanked up from Utah Beach. Winters at last had more men for his final attack. He found Malarkey and Toye asleep in a barn. “Malark, Toye!” he called. “Let’s go. Hang tough!” That was all they needed. The two men followed Winters out of the barn.

Winters led his new force back to the field, approaching this time behind the machine-gun nests. The men ran alongside the tanks, firing at anything that moved. There was no opposition. Soon all was quiet, with the exception of a few moans and groans from the remaining wounded Germans. There would be no more trouble from Brécourt Manor. The three-hour battle finally over, Winters was the last man to leave.

Aftermath

For his leading role in the battle, Winters was recommended for the Medal of Honor. It was downgraded, however, to a Distinguished Service Cross. There was an unwritten agreement among the airborne division commanders who fought on D-Day that only one Medal of Honor would be awarded per division during Operation Overlord/Neptune. (Lt. Col. Robert G. Cole, commanding the 3rd Battalion, 101st Airborne, earned the award for leading a bayonet charge against German positions near Carentan on June 11, but was killed in Holland during Operation Market-Garden before he could receive it.) Several groups have since tried unsuccessfully to upgrade Winters’s commendation.

The fight for Brécourt Manor proved the leadership of the 2nd Battalion’s officers and the fighting quality of its men. Winters had devised a quick, sound strategy and saved the lives of at least two of his men through his attention to detail and quick thinking. Compton led by example and did not tolerate poor behavior, even amid a battle. Speirs charged, hell-for-leather, the last gun. None of the officers hesitated during those trying hours in the trenches. The airborne noncommissioned officers and enlisted men also proved themselves warriors. Fighting for the first time, on little sleep, outnumbered, and in an unfamiliar area, they bested a part of the veteran German war machine.

The battle was a victory for the entire 2nd Battalion of the 506th. Lieutenant Winters led elements of Easy and Fox Companies, as well as paratroopers from battalion headquarters, to capture the first three guns. Dog Company, supported by a few Fox men and a single Easy man, captured the final gun. Teamwork and training proved invaluable to the men who wore the Screaming Eagle on their shoulder.

The battle for Brécourt Manor has become the stuff of legend. Besides being the one of the best documented small-unit actions of D-Day, in 1992, historian Stephen Ambrose published Band of Brothers, a history of Easy Company’s exploits in World War II; the battle is well depicted in its pages. In 2002, HBO premiered a television miniseries of the same title, recreating the battle for a national audience.

In addition, Dick Winters, who corresponded with the veterans of Brécourt for Ambrose’s book, donated his entire collection to the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center at the Army War College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Aspiring leaders can now examine the battle, and other Easy Company experiences, for themselves.

Altogether, 21 paratroopers attacked approximately 50 Germans and successfully disabled four artillery pieces. Winters noted in his autobiography, “In all, we had suffered four dead, six wounded, and we had inflicted 15 dead and 12 captured on the enemy.” It was a lopsided victory for the outnumbered paratroopers.

Winters said, “Even though Easy Company was still widely scattered, the small portion that fought at Brécourt had demonstrated the remarkable ability of the airborne trooper to fight, albeit outnumbered, and to win.”

Buck Compton had his own view of the battle’s outcome. “History has shown that troops landing at Utah Beach had an easier time landing due in part to what was accomplished at Brécourt. I’m happy about that. If our actions saved any of our boys’ lives, that’s part of what we were there to do.”

He added, “There’s a sense of guilt that will always be part of the war for me. It’s the guilt I feel from making mistakes. It’s the guilt I feel because I survived. Surviving a war is such a tricky thing. Why does one man live through a chaotic situation when another man doesn’t? Out of all the horror of war, the guilt of survival is one of the things that haunts me most to this day. I will never know why I survived when so many others did not. When it comes to understanding any of this, I have long since given up trying.”

I’ll comment only on two errors here:

“Guarnere had let loose, slaughtering men and animals with his rifle.”

— Guarnere had a Thompson, not an M1

“The grenade rolled off and the pin fell out.”

Unless this was not the common German “stick grenade,” those did not have “pins:” the bottom had a threaded cap that had to be unscrewed to access the string to pull and arm the grenade.

Editors??

Thanks for your comments. Author Kevin Hymel replies: William Guarnere said he lost his weapon during the D-Day jump, like Dick Winters and others. I do refer to him carrying a Thompson in the attack, and have corrected the rifle reference. Regarding the comment about the stick grenade, your are correct. However, that is how Buck Compton described the incident.

Milhan, not Winters killed in glider crash