By Peter Kross

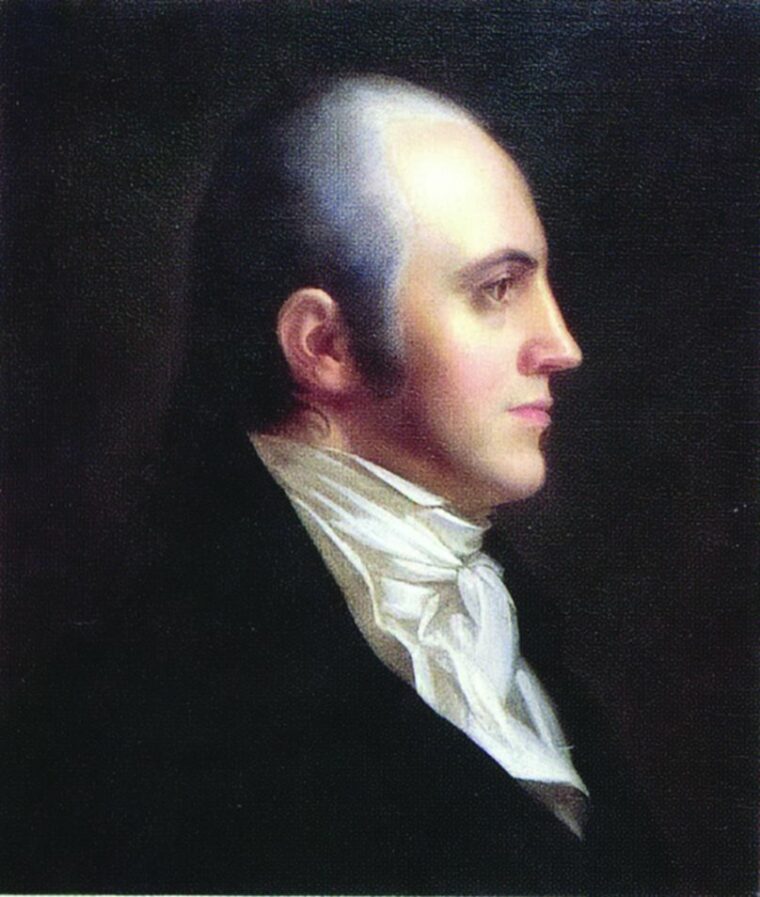

Two names stand out as quintessential villains in early American history—Benedict Arnold and Aaron Burr. Arnold, a valued general in the Revolution, fought alongside George Washington, but changed sides and offered to turn over West Point to the British. Burr, the former vice president of the United States, killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel in New Jersey, and later plotted an insurrection to form a separate country in the southwestern United States, with Burr as its head.

One of Burr’s accomplices in the conspiracy was James Wilkinson, also a general in the American Revolution. Wilkinson, a veteran of the Quebec campaign with Benedict Arnold, was a student of medicine and a man with a giant ego. Unknown to most Americans today, Wilkinson, while serving as an officer of the American Army, secretly worked as a spy for the Spanish government, which designated him “Agent 13.”

Wilkinson was born on March 24, 1757, near Benedict, Maryland. His father was a well-to-do merchant, and when James came of age he was sent to Philadelphia to study medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Forced to drop out when the American colonies took up arms against the British, Wilkinson joined the military. His first assignment was in a Pennsylvania rifle battalion. He rose to the rank of captain in September 1775, later serving as an aide to General Nathanael Greene during the siege of Boston. His next assignment was with Benedict Arnold when the latter took his troops to Quebec to battle the British. The Quebec campaign foundered when the British put 8,000 men into the field, and the Americans were forced to retreat. After the Quebec defeat, Wilkinson served under General Horatio Gates in 1776.

Wilkinson was soon involved in another fiasco, this time at the Battle of Fort Ticonderoga, a vital stronghold overlooking the Hudson River. The fort had originally been captured by the colonists under Ethan Allen, but after Gates arrived, the important bastion fell back into British hands. After the defeat, Gates asked Wilkinson to keep quiet about the loss of the fort.

Wilkinson, promoted to brigadier general, always seemed to be at the wrong place at the wrong time. He became involved in a plot by several American military officers, called the Conway Cabal, to overthrow General Washington. The plot was hatched by Thomas Conway, inspector general of the American Army, and Thomas Mifflin, Washington’s supply general. The plotters hoped to replace Washington with Gates. While drunk, Wilkinson inadvertently revealed the plot to oust Washington, but the American commander in chief did not take the threat seriously and decided not to prosecute Wilkinson. He allowed Wilkinson to resign from the Army in 1778. A year later, Wilkinson—a hard man to keep down—returned as clothier general of all American forces, but resigned again in 1781 amid charges of graft and corruption.

Increasingly out of favor with top political and military figures in the colonies, Wilkinson headed west into the uncharted land beyond the Appalachian Mountains. In 1784, he arrived near the Falls of the Ohio (present-day Louisville, Kentucky), where he started a large farm and became one of the most influential persons in the region. At that time, the fledgling government in Washington had little influence over inhabitants of the sparsely settled yet abundant land, and a number of ambitious people looked to Spain (which still controlled the Mississippi River) for their bread and butter.

For a time, Kentucky and other states in the region toyed with the idea of leaving the United States, forming their own government or uniting with Spain. Many wealthy men in Kentucky and elsewhere were unhappy that Spain did not allow the free use of the Mississippi to U.S. citizens who wanted to take their produce back east. They hoped to reach a separate accommodation with the Spanish.

In 1778, before heading west, Wilkinson had been secretly corresponding with Aaron Burr, using a code that only they understood. Wilkinson, running a supply store in Lexington, was on the road every day, meeting with all sorts of people and gaining their trust and influence. He lobbied hard for statehood for Kentucky, telling all who would listen that if independence was won, the people of Kentucky could hitch their wagons to either the United States or Spain. In the end, Kentuckians remained loyal, despite Wilkinson’s ongoing efforts to foment dissension.

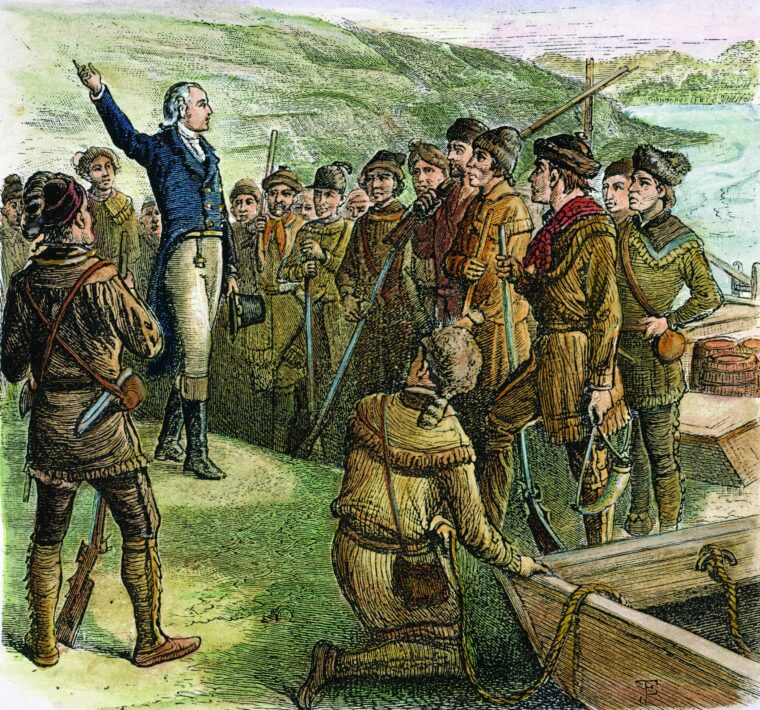

In 1787, Wilkinson, who had failed to get a permit from the governor of Virginia to sell his tobacco and other goods to the Spanish, nevertheless took a boat down the Ohio River to New Orleans. Upon his arrival, he wangled an introduction to the Spanish governor of Louisiana, Don Esteban Rodriguez Miro, who allowed Wilkinson to sell his goods on the open market. Soon the two men reached a secret agreement. Wilkinson took an oath of allegiance to Spain, becoming a subject of the Spanish government, and was paid $2,000 and granted exclusive rights to sell his tobacco and other goods along the Mississippi River. He was given a code number 13 to use as his cover when dealing with the Spanish authorities in the region. Wilkinson became, in effect, a spy for Spain.

In November 1788, Wilkinson came into contact with Dr. John Connolly, an Englishman who was born in America. Connolly told Wilkinson he was an agent for the British government who wanted to raise an army of 10,000 men for the purpose of seizing Louisiana from Spain. Thinking quickly, Wilkinson devised an ingenious and self-serving plot. He informed Miro about Connolly’s machinations, while seeming to cooperate with the English plot. After saving Connolly’s life in an assassination attempt by a Spanish agent, Wilkinson found himself in the good graces of both Spain and Great Britain, a position he would use for his own devices.

Despite his best scheming, Wilkinson found it impossible to make a good living. He was forced to return to Kentucky, where in 1791 he led a force of volunteers against Native American rebels in the Old Northwest For his Indian-fighting efforts, Wilkinson was commissioned a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army and made commander of the 2nd U.S. Infantry. He was promoted to brigadier general in 1792, all the while remaining Agent 13 for the Spanish government. In 1796, he became senior officer in the Army after General “Mad” Anthony Wayne’s death. Wilkinson spent most of his time in Natchez and Baton Rouge, commanding a reserve corps in the lower Mississippi River valley—ironically guarding against an invasion by France and its chief ally, Spain.

Wilkinson’s fortunes improved mightily when France decided to sell the Louisiana territory to the United States. When the United States took control of Louisiana Territory in December 1803, Wilkinson was in New Orleans, where he was given the job as the highest ranking military officer in the new American crown jewel. In time, Wilkinson would be rewarded with the vital post of governor of the Louisiana Territory, a post that would make him one of the most influential men in the United States. He found time to reconnect with Aaron Burr and set in motion the events that would culminate in the so-called Burr Conspiracy.

Prior to his involvement with Burr, Wilkinson was already up to his neck in nefarious schemes. In 1805, he used his authority to send Zebulon Pike on a military espionage mission up the Mississippi River. His orders were to explore the largely unmapped Mississippi region and purchase land for potential military posts from the Native Americans who inhabited that region.

Wilkinson may have had an ulterior motive for sending Pike on his journey. While there is no verifiable proof that Wilkinson and Burr were teaming up at this particular time, Wilkinson may have ordered Pike to proceed secretly into the heart of the Spanish Southwest to spy on garrisons in New Mexico and other locations as part of the Burr Conspiracy.

After Burr killed his political nemesis, Alexander Hamilton, in a duel on July 11, 1804, in Weehawken, New Jersey, Burr fled to the West to escape the murder charges leveled against him. Wilkinson and Burr heated up their plans to create a new nation west of the Alleghenies. It is unclear who was the real driving force behind the conspiracy, but with Wilkinson serving as governor of the Louisiana Territory, certainly no one was better qualified to chart the political and military landscape.

For conspiracy theorists, the smoking gun in the entire affair is a coded letter that was sent by Burr to Wilkinson on July 29, 1806. The letter was sent from Philadelphia and given to Wilkinson in Louisiana by Samuel Swartwout, a friend of Burr. The relevant parts of the Burr cipher read as follows: “Yours postmarked 13 May is received. I have obtained funds, and have actually commenced the enterprise. Detachments from different points under different pretences will rendezvous on the Ohio, 1st November—everything internal favors views—protection of England is secured. Truxton is gone to Jamaica to arrange with the admiral on that station, and will meet at the Mississippi-England-Navy of the United States are ready to join, and final orders are given to my friends and followers—it will be a host of choice spirits. Wilkinson shall be second to Burr only—Wilkinson shall dictate the rank and promotion of officers. Send a list of all persons known to Wilkinson west of the mountains, who could be useful, with a note delineating their characters.”

Burr’s plan was to move rapidly from the falls on November 15, with the first 500 to 1,000 men, in light boats to arrive at Natchez between December 5 and 15, and meet up with Wilkinson to determine whether it would be expedient to seize on or bypass Baton Rouge.

By then, however, Wilkinson’s political fortunes had taken a drastic turn for the worse. He was removed by President Jefferson from his post as governor of Louisiana Territory after familiar allegations that he had abused his power. Ever the opportunist, Wilkinson told the president about the Burr Conspiracy—failing to mention his own role in the plot.

Burr went on trial for conspiracy and Wilkinson was one of the witnesses against him. The Burr trial was a heated affair, and despite the inflammatory testimony by Wilkinson and others, the jury found that there was no concrete evidence to convict Burr of treason. In the aftermath of the Burr trial, Wilkinson’s reputation was badly damaged and his alleged actions regarding Burr came under intense congressional scrutiny. President James Madison ordered him court-martialed in 1811, but he was acquitted on Christmas Day of that year.

During the War of 1812, the experienced Wilkinson was commissioned a major general, despite his long association with Burr, and proceeded to occupy Mobile in Spanish West Florida. Reassigned to the St. Lawrence River sector, he led his troops in the disastrous Battle of Montreal. With his military reputation in ruins, Wilkinson left for Mexico City, where he hoped to receive a lucrative Texas land grant in recognition of his prior service to Spain. While there, he wrote Memoirs of My Own Times, a typically exculpatory and self-serving account of his various military, diplomatic, and financial misadventures. He died in Mexico on December 28, 1825.

It was not until 1854 that Wilkinson’s true involvement with the Spanish government came to light with the publication by Louisiana historian Charles Gayarre of the correspondence between Wilkinson and Rodriguez Miro, his original Spanish case officer. Since then, historical judgments of Wilkinson have been harsh. Robert Leckie called him “a general who never won a battle or lost a court-martial,” and Frederick Jackson Turner labeled him “the most consummate artist in treason that the nation ever possessed.” George Rogers Clark took a somewhat more measured view, conceding that Wilkinson “had considerable military talent, but used it only for his own gain.” It seems a fair assessment.

Insightful read. Well done.