By Kelly Bell

In the months after the U.S. Navy was taken by surprise at Pearl Harbor, fleet commanders vowed that their sly Imperial Japanese enemy would never again sneak up on them, and at first this promise held true. Off Midway, it was the Japanese who were caught off guard and sent reeling. Yet one facet of the great American triumph went overlooked in the post-battle euphoria—the clash had been fought on and above a sun-washed seascape whose visibility extended to the curved horizons. American sailors were not trained to wield their weapons in darkness. Their counterparts, however, were well versed in this cunning martial art, and their surface fleet was still vast and potent.

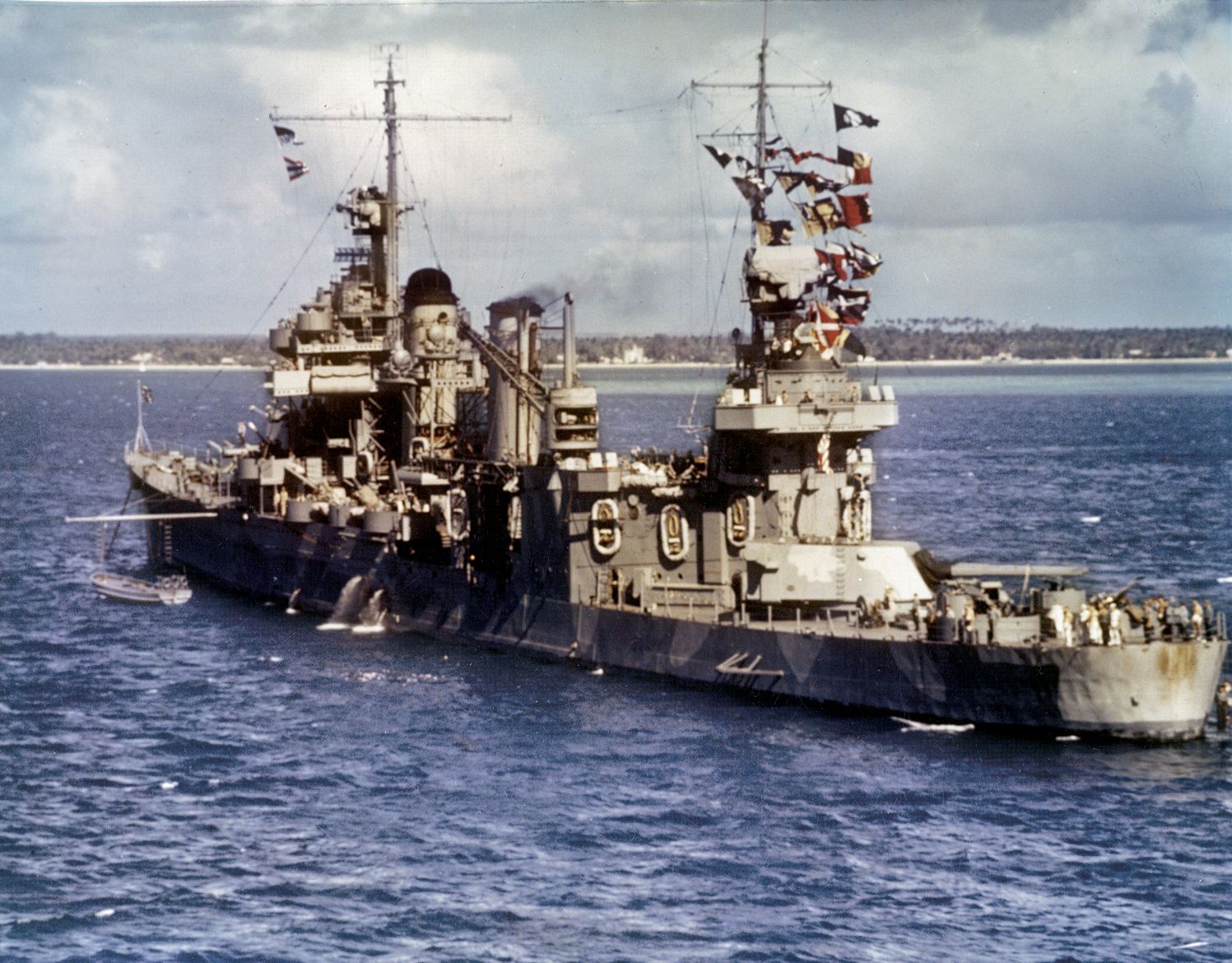

Admiral Chester W. Nimitz’s Pacific Fleet forces were quickly learning the new doctrine of aircraft carrier-dominated warfare, but it was distracting them from old battleship tactics whose firepower was still of extreme consequence. The most significant cruiser battle of the war was shaping up off the Solomon Islands, where a U.S. Navy flotilla was supposed to provide critical offshore artillery support for Maj. Gen. Alexander Vandegrift’s 16,000 Marines who had just landed at Guadalcanal.

Like the rest of the Navy, the Solomon Islands task force was less experienced than its adversary. Its prewar core of seasoned seamen had been scattered throughout the suddenly far-flung fleet as wartime military expansion created a crying need for old salts to train the hordes of rookie sailors. Getting the newcomers battle ready as soon as possible left insufficient time for nocturnal drilling, which had never been emphasized in the first place. American sailors did not know how to fight in darkness. This would cost them dearly in the initial stages of the Guadalcanal campaign.

Japan’s navy, by contrast, had a long tradition of night fighting. Its men were meticulously trained in this element of warfare, and they were also well aware of the U.S. Navy’s neglect of it.

Apart from superior Japanese training, a critical factor was the advanced state of Japanese weaponry. Following extensive post-World War I experimentation with various types of torpedoes, the island nation’s naval technicians had discarded air-powered propulsion systems and commenced perfecting and manufacturing waterborne missiles fed by volatile, powerful pure oxygen. By 1933, the peerless Type 93 “Long Lance” was being delivered. Its robust engine could push a 1,090-pound warhead along a straight, wakeless, 11-mile track at 49 knots. It was a very unfortunate target indeed that suffered even a glancing blow from the new, infernal weapon.

Despite the recent pivotal victory off Midway, most American tacticians still clung to the ingrained truism that a warship’s deck guns were her dominant armaments. They preached a doctrine of advancing to within artillery range of hostile squadrons and opening accurate shellfire while still outside the presumed reach of the enemy’s torpedoes. The U.S. Navy had yet to encounter the Long Lance, and this fearsome weapon would prove horrendously effective.

The Japanese fleet approaching Guadalcanal in early August 1942 was laden with vast stores of the Type 93, and its sailors were quite expert in their use. The joint American-Australian task force guarding the Marine beachhead carried few torpedoes. Those they did carry were of inferior quality, and the seamen were ill-trained in their deployment in nighttime combat. The American Mark XV torpedo sported a far smaller warhead than the Long Lance and was limited to just three miles at 45 knots. Furthermore, its notoriously unreliable depth-setting mechanism and magnetic-influenced exploder resulted in few successful attacks. The missiles usually passed harmlessly under their targets, exploded prematurely, or failed to explode at all.

Admiral Gunichi Mikawa began assembling his attack force on August 7, the day of the Marine landing at Guadalcanal. Four heavy cruisers were joined by the elderly light cruisers Yubari and Tenryu and the equally aged destroyer Yunagi. Aboard his heavy cruiser flagship Chokai, Mikawa dispatched the old transports Meiyo Maru and Soya with 519 rifle-armed sailors in hopes of reinforcing the land forces straining to shove the Marines from their tiny perimeter in the Pacific. However, the motley troop convoy chanced across the bow of Lt. Cmdr. Henry Munson’s S-38 submarine. The sub had been built in 1909 and was armed with old, reliable Mark X torpedoes that featured simple, dependable contact detonators. When Munson stuck one of these rusty charges into Meiyo Maru, she sank like a sandbag, taking 373 Japanese sailors with her.

This was just one worrisome factor Mikawa had to confront. The crews of his cruisers were sharply honed teams that operated in lethal harmony, but the other vessels in the hastily gathered assembly were strangers to each other and unlikely to perform with a great deal of efficiency in combat. Also, Mikawa’s shortage of destroyers would leave his command open to the fate of Meiyo Maru. Without the speedy little war boats to screen the more ponderous vessels from American subs, the flotilla was not only susceptible to sniping submersibles, but also to having its presence detected and betrayed by undersea prowlers. Apart from the venerable Yunagi, there were no destroyers available. Mikawa decided that the risk was acceptable, and at 2:30 pm the fleet churned from Rabaul’s Simpson Harbor and steered for Guadalcanal in a manner so brazen that American pilots patrolling from aircraft carriers anchored off the Solomons never dreamed that they should watch for such a move.

On the morning of August 8, Japanese reconnaissance aircraft out of Rabaul located the American supply ships anchored off Guadalcanal. The airmen counted three heavy cruisers, several destroyers, and 13 additional cargo carriers moored just off adjacent Tulagi. Moving his command to an out-of-the-way patch of ocean east of Bougainville, Mikawa sent three floatplanes aloft later that morning. The aircraft sniffed out more potential victims off Lunga Point and the opposite side of Tulagi.

At this point, a twin-engine Lockheed Hudson bomber buzzed the raiders. Chokai’s antiaircraft gunners opened up on the snooping aircraft and scared it away. Fearing that his ships had been reported and would soon be assaulted, Mikawa dispersed the vessels and made ready to defend against American torpedo planes. In a never-resolved mystery, the air crew either did not report its crucial sighting or else had its alarm disregarded. It is possible the airmen thought friendly vessels had mistakenly fired on them. Whatever the case, a relieved Mikawa watched the onset of sheltering darkness without having sighted a single U.S. warplane.

By this time he had turned his fleet southward at 24 knots, and although still worried about the American aircraft carriers’ whereabouts (they were safely concealed beneath thick cloud cover), Mikawa made his approach into New Georgia Sound. By 6:30 pm, all his warships were battle ready, and the admiral sent a blinker signal to his crews: “In the finest tradition of the Imperial Navy we shall engage the enemy in night battle. Every man is expected to do his utmost.”

The Americans and their Australian allies had laid out a multilayered defense grid of long-range search aircraft and radar-equipped picket destroyers. An inner perimeter of cruisers and destroyers provided a screen of floating artillery to shield the vulnerable Marine beachhead at Guadalcanal and the indispensable supply ships. On paper it looked like the search planes could blanket the region, but in practice the searchers would prove half blind.

Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boats patrolled the sea north and northwest of Guadalcanal, watching for any hostiles who might approach from Truk. Hudsons flown by Royal Australian Air Force pilots from airfields around Milne Bay, New Guinea, covered the south and southwest sectors. Twenty 11th Bomb Group Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses watched over the western approaches. The Catalinas and Fortresses were equipped with new ASE surface-search radar sets. These devices could detect surface craft from as far away as 25 miles, but there were still a few bugs in the system, and sets frequently malfunctioned.

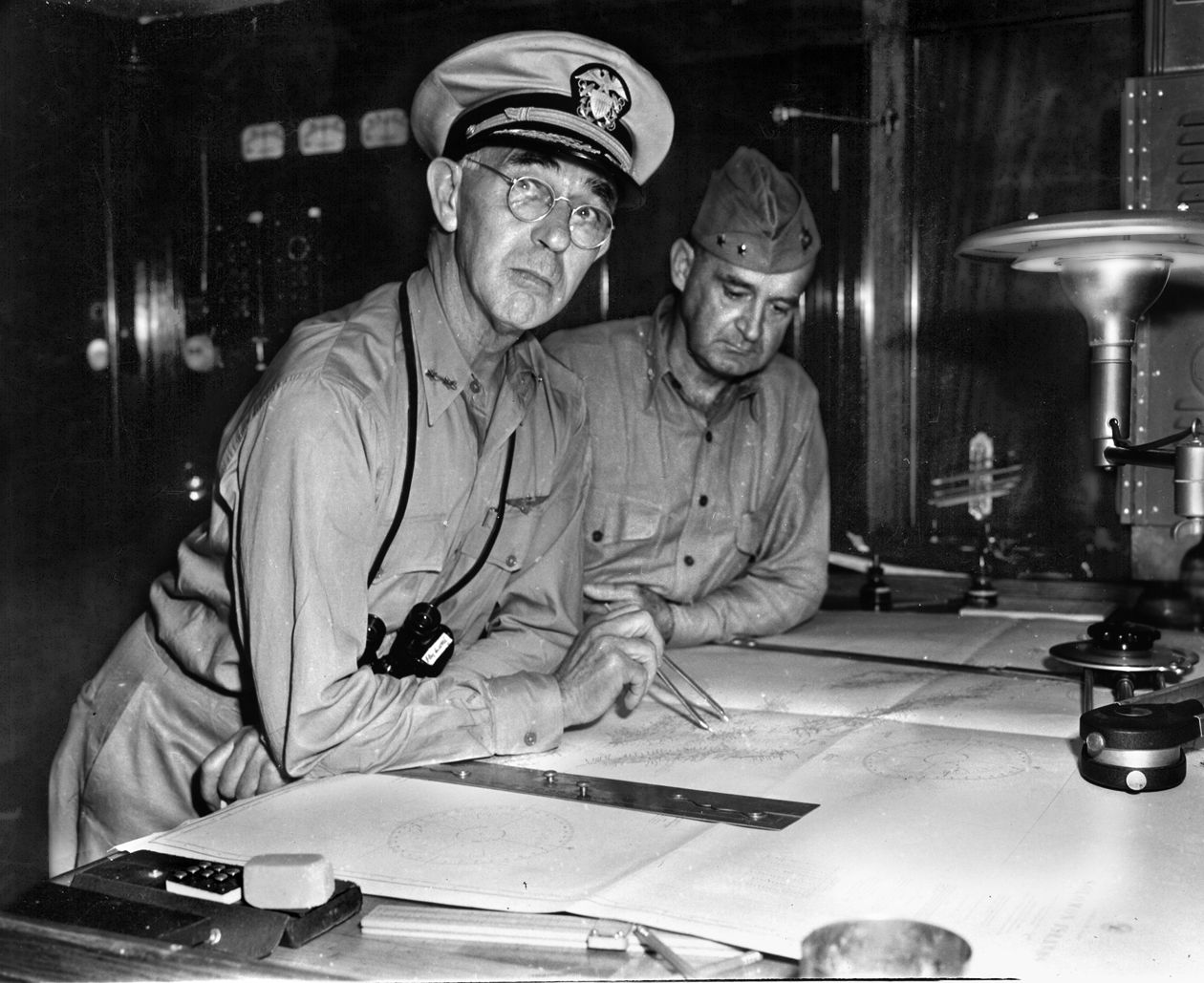

American Vice Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, commanding Carrier Task Force 61, recommended that planes prowling over New Georgia Sound time their search patterns so that they reached the ends of their outbound flights at dusk, then return the same way while probing with radar in case enemy elements should try to slip down the corridor under cover of darkness. Nobody bothered to act on Fletcher’s well-reasoned advice, and on the afternoon of August 8, Mikawa’s fleet easily eluded the porous air coverage. Fletcher was unaware his request for air reconnaissance had been ignored. He thought aircraft were patrolling the most likely route of approach by hostiles, and when he received no reports of danger in the channel he simply assumed there was none.

Incredibly, several nonreconnaissance units sighted Mikawa’s task force, but these reports were also ignored. As Mikawa’s warships commenced their high-speed advance, they were spotted by B-17s returning from a raid on Rabaul, and a second B-17 flight noted the flotilla churning southeast down St. George’s Channel. Most significant was a dispatch from S-38 warning that what sounded to her crew like two destroyers and three heavy cruisers had passed over her at 5:42 pm. No one bothered to inform Guadalcanal’s naval commander, Rear Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, of these contacts. Precisely as Fletcher had feared, the raiders entered the passage at dusk, and as the attack took shape the unwary Americans and Australians were vulnerable in the gathering twilight.

Earlier that afternoon, Fletcher had received an intelligence report that twin-engine Japanese torpedo bombers had been spotted over Guadalcanal, and he made what was perhaps the most critical error of the many Allied miscues leading up to the battle. Americans had first come to dread the enemy’s torpedo planes at Pearl Harbor. They had also wrought mayhem during the Battle of the Coral Sea when they damaged the aircraft carrier Lexington, and at Midway when they sank the carrier Yorktown. Learning that the feared torpedo planes were prowling in his vicinity, an unnerved Fletcher ordered his carriers to withdraw southeast to a safe distance. With the flattops no longer present to provide air cover, the transports and their guardians off Guadalcanal were open to attack.

Another opportunity had been squandered when the pilots of two Hudsons overflew the Japanese at 10:25 and 11 am and inexplicably waited until they landed back in New Guinea to sound the alarm. Furthermore, they underestimated the speed of the vessels. The dispatches indicated the ships were moving at just 15 knots, leading Turner to calculate that they would not reach Guadalcanal that night. The airmen even mistook the task force’s heading, causing Turner to conclude that it was not coming his way.

Nevertheless, it was sufficiently worrisome for Turner to summon Vandegrift and British Rear Admiral Victor A.C. Crutchley, commander of Cruiser Task Force 44 (Hobart, Chicago, Canberra, and Australia) to discuss the situation. With Fletcher having already departed with his carriers, the conference meant that every senior Allied commander was away from his unit. Mikawa’s leaderless victims were ready to be harvested.

As the Japanese steamed down Savo Sound, staying undetected behind 1,673-foot Savo Island, Crutchley positioned Australia, Canberra, and Chicago just south of Savo Island to watch for raiders who might approach from the west. The northern passage was staked out by the cruisers Vincennes, Quincy, and Astoria. Crutchley critically neglected to ascertain that the captains of the northern and southern groups were aware of each other’s positions. He also sent out seven of his nine destroyers as antisubmarine pickets, effectively removing them from the defensive shield at Guadalcanal.

At 11:30 on August 8, the usual late-night thunderstorms formed east of Savo Island and drifted directly into the path of the hurtling attackers, cloaking them from aerial and shipboard spotters. As the raiders charged down the passage, Blue, an old U.S. Navy picket destroyer, cut directly in front of them, but Blue’s navigators were concentrating on navigation landmarks to the east and did not notice the lethal fleet bearing down from the opposite direction. Moments later, at 12:43 am, the attackers passed unnoticed behind the destroyer Ralph Talbot, one of the few torpedo-armed Allied ships in the area.

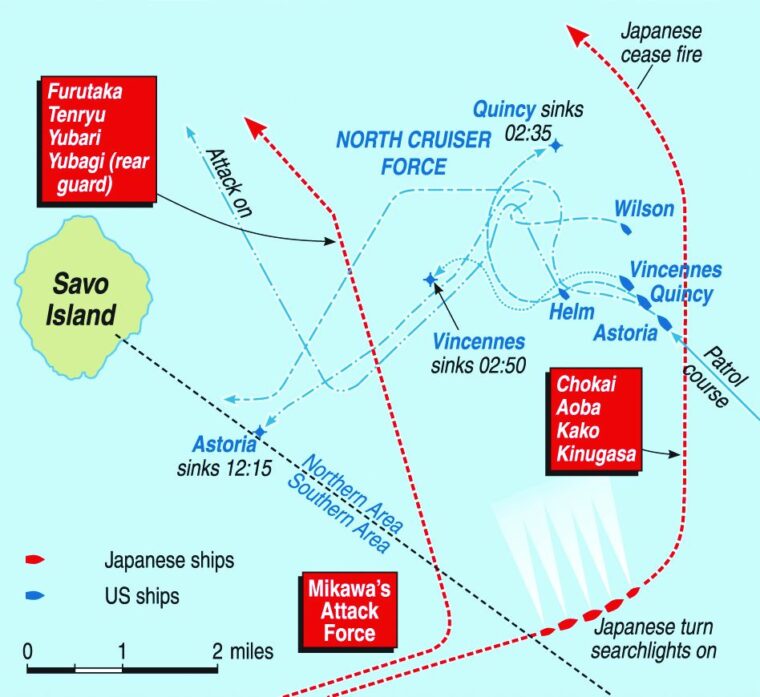

The Japanese had sounded battle stations at midnight and accelerated to 26 knots while assembling into combat formation. From Chokai, Mikawa led Aoba, Kako, Kinugasa, Furutaka, Tenryu, Yubari, and Yunagi. The Japanese squadron was still undetected as it passed south of Savo Island. At 1:33 am, Mikawa broke radio silence to order his captains to increase speed to 30 knots, then yelled, “All ships attack!” into his microphone.

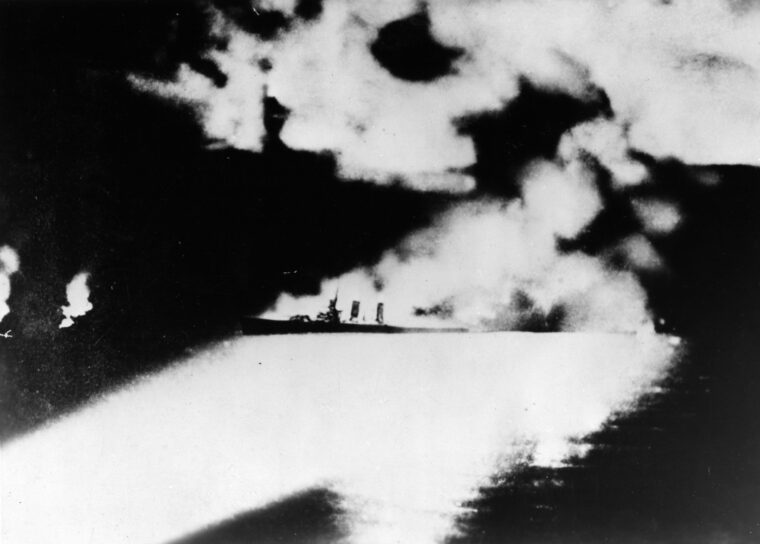

Surging from an opaque curtain of rain, Chokai uncorked four torpedoes at Canberra; Furutaka and Aoba swiftly followed suit. The trio also opened fire with deck guns on the Australian cruiser and quickly set her ablaze. Within five minutes Canberra was dead in the water, her crew decimated and her radios inoperable. Straining against her 30-degree starboard list, survivors watched in horror as their attackers pounded past them, guns blazing, deeper into the harbor.

At 1:46 am, Chicago’s helmsman alertly jerked her hard to port to dodge two torpedoes, but seconds later another torpedo from Kako ripped open her starboard bow. Captain Howard Bode, awakened from a sound sleep, turned his wounded vessel west to face the Japanese, and presented them with the smallest possible target. Searching wildly for the still invisible enemy, Chicago’s gunners managed to discern some unfamiliar vessels attacking the destroyer Patterson. Opening up with his 5-inch rifles, Bode killed 23 of Tenryu’s sailors with a direct hit but mysteriously held a static position west of the harbor while the fighting moved south. Even more puzzling, he failed to broadcast a radio report of the developing battle. By this time, Patterson’s skipper, Commander Frank Walker, was desperately filling the airwaves with a panicky message of his own: “WARNING! WARNING! STRANGE SHIPS ENTERING HARBOR!” Walker’s gunners gamely cut loose on Tenryu, Yubari, and Kinugasa, pumping 5-inchers at them until 2:10 am, when he received a radio message from Crutchley to disengage.

After just seven minutes, Turner’s southern cruiser force was blazing wreckage, and Mikawa turned his prows north. The rain squall was still roiling the waters. The downpour concealed the raiders’ approach and masked the muzzle flashes and conflagrations from the Americans to the north. As the Japanese moved away from their crippled and sinking victims and reentered the deluge, Furutaka, Tenryu, and Yubari became separated from the rest of the fleet and emerged from the storm front in single file slightly west of their sister ships. This unplanned positioning placed the attackers on parallel courses that would trap their quarry between them in a killing crossfire.

At 1:48 am, Mikawa lined up his forward torpedo tubes on Vincennes and fired a four-shot spread from 12,000 yards. The missiles missed, but seconds later Vincennes, Quincy, and Wilson were caught in the blinding rays of searchlights from Chokai, Kako, and Aoba. At 1:51 the Japanese began firing their main batteries at their startled victims. After just four minutes the Allied warships were badly damaged and in no condition to retaliate, but at this point the killers began to lose formation, making it difficult for either side to tell friend from foe.

Astoria’s crew was totally unaware of the attack; most were sleeping when Chokai fastened her spotlights on them. By sheer coincidence, gunnery officer Lt. Cmdr. William H. Truesdell was near the main battery director when Mikawa’s first salvo battered the water around the American cruiser. Truesdell instantly rang the bridge and cried out for general quarters, but watch supervisor Lt. Cmdr. James R. Topper did nothing. Realizing that vital time was waning, Truesdell independently ordered the main batteries to commence firing. Astoria’s skipper, Captain William G. Greenman, stumbled half asleep onto the bridge and asked Topper who had given the order to fire. When his subordinate professed ignorance, Greenman drawled: “Topper, I think we are firing on our own ships. Let’s not get too excited and act too hasty. Cease firing!” An instant later Truesdell came over the intercom and wailed, “For God’s sake, give the word to commence firing!” A crucial four minutes had passed since the Japanese opened fire. It was now too late.

At 2:16, Astoria was too badly damaged to still be a threat, and it was now safe for Kinugasa to give away her own position, so she turned her light onto the burning ship to make it easier to finish her. Lt. Cmdr. Walter B. Davidson climbed onto Astoria’s number two turret and verbally directed a final salvo. Using the last of their electrical power, the gunners trained their five-inchers on Kinugasa and fired their ship’s last volley, missing their intended target but scoring a direct hit on Chokai immediately behind her. Mikawa’s foremost main battery was pulverized, killing or wounding 15 men. Seconds later, Astoria’s remaining power reserves fizzled out and she coasted to a halt, an inferno of oily flames.

Just before the shelling started, Quincy’s radio operators had picked up Patterson’s wireless warning of the oncoming strike force, and Captain Samuel Moore did not hesitate to sound general quarters. As the enemy’s lights stabbed through the sodden blackness, Moore received radio orders to steam at 15 knots and fire on the lights, but his main battery was not yet battle ready. Before the gunners could finish priming their weapons, Aoba struck Quincy with a blizzard of shellfire, wrecking her bridge and fantail. One round hit a floatplane in the well deck and spattered the area with flaming gasoline from the aircraft’s fuel tank.

Furutaka and Tenryu joined the attack, trapping Quincy in a three-pronged crossfire. Realizing that he was sandwiched between two columns of hostiles, Moore ordered his helmsman to maneuver hard to starboard to avoid colliding with Vincennes. The maneuver set Quincy on a direct heading for the eastern group of Japanese cruisers, earning her instant admiration from the Japanese for what they later called her crew’s great spirit. At 2:04 am, two Long Lances from Tenryu disemboweled Quincy, and in a final act of defiance Moore’s gunners fired a broadside at Kako. In another incredible fluke of gunnery, the salvo missed its intended mark and crashed into Chokai instead, destroying Mikawa’s chartroom and killing or crippling another 36 of his men.

At 2:10, another direct hit killed Moore and his bridge staff, and six minutes later a torpedo from Aoba holed Quincy’s port side. At this point the raiders ceased firing on the pugnacious but plainly dying American ship, and at 2:38 she sank bow first. By battle’s end, she would be one of so many warships on the sea floor that the sector would forever be known as Iron Bottom Sound.

Aboard Vincennes a befuddled Captain Frederick L. Riefkohl tried to raise Crutchley on the radio and obtain some information about the chaos. At 1:53 am, Kinugasa had trained her searchlight on Vincennes, and Kako then assailed her with main and secondary batteries. Turning from sinking Quincy, Chokai joined in the shelling as Mikawa maneuvered his eastern group toward the reeling Americans. He was attempting the ancient naval tactic of crossing the “T” and placing him in position to let loose broadsides at the Allies, who would be unable to reply except with their handful of after turrets.

Riefkohl had no trouble diagnosing his opponents’ intentions. After screaming for 20 knots of speed, he ordered his helmsman to turn 40 degrees to port and yelled for his gunners to fire on Kinugasa. The second volley knocked out the Japanese ship’s steering gear and convinced her crew to switch off its searchlight—not that it was really needed anymore, since Vincennes was burning violently. Still, Riefkohl had disrupted Mikawa’s T-crossing stratagem.

At 1:55, realizing what a conspicuous target his flame-shrouded boat had become, Riefkohl turned to starboard and asked for 25 knots in an effort to split up the savaged clump of Allied warships, making them a smaller collective target. Before Vincennes could get underway, a Long Lance from Chokai shattered her forward port hull, and Tenryu and Furutaka opened their deck guns on her. At 2:03 am, Yubari drilled a torpedo into Vincennes’ number one fire room, killing every man there and silencing her last operable battery. Still wondering if he was under friendly fire, Riefkohl ordered a different set of colors hoisted. This confused the Japanese into thinking they were pummeling one of their own ships, and for seven minutes they ceased fire. At 2:13, Mikawa and his officers realized all their boats were accounted for and resumed hammering Vincennes. At 2:30 Riefkohl gave the order to abandon ship; at 2:58 she gurgled to the bottom.

After finishing their latest victim, the Imperial pincers resumed closing toward the northeast. Ralph Talbot had slipped alongside Yubari in hopes of staying unnoticed long enough to loose a spread of torpedoes, but the Japanese cruiser’s crew instantly spotted the sleek shadow and wrecked her with five direct hits. The storm saved Talbot from further damage as she lurched away under the gushing clouds, making for the shallow anchorage just off Savo.

While Yubari’s gunners were crippling Talbot, Mikawa was gathering his command staff around him. Despite his squadron’s having sustained little damage and having plenty of ammunition remaining, it had totally lost formation. The admiral and his officers estimated that it would take two hours to reassemble their fleet and deploy to attack the transports. This would leave just one hour of darkness, and if the American carriers were en route to the area, aircraft would likely intercept the raiders before they could reach their next targets. There was also the possibility that if they departed right away the attackers might use themselves as bait to coax vengeful American carrier commanders into following within range of Japanese torpedo planes based on Rabaul.

The Imperial Navy had already won a smashing victory that night. Surviving Allied naval elements had quit the area and were steaming eastward at best speed. At 2:20 am, Mikawa ordered his own fleet to withdraw. This flabbergasted some of his captains, who had never dreamed their exalted admiral would not perform the final task of the operation by destroying the helpless Allied supply flotilla. The freighters were much more significant than Mikawa realized, and by sparing them he committed a fatal error that grievously tainted his victory and eventually tilted the Solomons campaign against Japan.

Although he grudgingly complied with the order to come about and head west, Kinugasa’s captain, Masao Sawa, blew every one of his starboard torpedoes from their tubes in a futile effort to strike the transport anchorage 13 miles away. Aboard Chokai, Captain Mikio Hayakawa pleaded vainly with Mikawa to destroy the cargo ships before leaving the area, but by 3:40 am the raiders had regained formation and set out for home.

Later that morning, U.S. sub S-44 stalked to within 700 yards of Kako and pumped three old-fashioned torpedoes into her; five minutes later she went down with 71 of her men. Meanwhile, back in the debris-choked waters around Savo Island, Quincy and Vincennes were already on the bottom. The fires on Canberra were being held somewhat in check by the pounding rain, but Turner soon realized the mangled vessel was beyond salvaging, and at 8 am he had the destroyer Ellet sink her with a torpedo. The deluge also delayed Astoria’s last rites. The storm adequately extinguished her blazing topside, but internal fires continued to spread. With her insides being wracked by explosions, the last of her men abandoned ship at 12:05 pm. Ten minutes later she rolled onto her port side and sank stern first.

Like his counterpart, Fletcher was also disregarding good advice. When Fletcher finally saw battle dispatches at 5 am, he declined to come about and pursue the Japanese, citing the threat of enemy airpower from nearby Rabaul. He was unswayed by arguments that he could launch dive bombers and torpedo planes from his own carriers against the withdrawing strike force and still retain his fighter planes in case enemy aircraft appeared. Instead, the carriers that Mikawa so feared maintained a timid distance.

Fletcher also refused to return to Guadalcanal to provide air cover for the continued unloading of the transports. At 2:15 pm on August 10, he turned over his position as expeditionary force commander to Turner. Although the aircraft carriers were long gone by then, the new commanding admiral made a gutsy decision to return to Guadalcanal and furnish whatever protection he could to the freighters despite his destroyers and remaining cruisers being dangerously vulnerable to air attack. Turner assembled the remnants of his command and shepherded the merchantmen eastward after their cargoes had been offloaded.

Vandegrift’s Marines were now alone and encircled, but they had just enough arms, food, and medical supplies to sustain them until help could arrive. The haughty Japanese land forces would soon be soundly defeated in battle at the Ilu River and the heights overlooking Henderson Field. When the Japanese attempted an overly complicated offensive to assault the American perimeter from the interior of the island, large numbers of their troops became lost in the jungle and wandered aimlessly around until they succumbed to starvation, tropical disease, or Marine bullets. Had Mikawa completed his mission, the Marines would have had insufficient ammunition to defend themselves and would almost certainly have lost Guadalcanal. As at Pearl Harbor, excessive Japanese caution saved the Americans from total defeat.

Some 1,077 Americans and Australians died in the Battle of Savo Island, and another 700 were wounded. When the American destroyer Jarvis went down later that morning in a Japanese air attack, she took another 233 men with her. A half century later, undersea explorers were horrified by the number of sunken vessels littering the sea floor in Iron Bottom Sound.

When a beaming Mikawa made it home, he was stunned to learn that Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander of the Combined Fleet, was not entirely pleased with his spectacular but incomplete victory. Having traveled extensively in the United States, Yamamoto had a better grasp than most Japanese of America’s industrial capabilities. He realized that his little island nation could not win a prolonged war against a country with such massive reservoirs of men, material, and natural resources, and that a long step closer to the quick finish that was Japan’s sole hope of victory had been squandered. His navy’s reverses in the recent battles of Coral Sea and Midway had spawned momentum for the Americans. Off Savo Island, Mikawa could have crushed this swelling impetus while securing the Solomons as a base of operations for resurgent air and sea offensives. Instead, he flinched.

Following the battle, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox ordered Admiral Arthur J. Hepburn to convene a board of inquiry to clarify the causes for the humiliating defeat. Hepburn dug tirelessly into every aspect of the affair. After a comprehensive review, he blandly attributed the overriding reason for the defeat to “the complete surprise achieved by the enemy.” He blamed the fleet’s being taken so utterly unawares on its poor state of readiness in the event of night attack, its failure to react to repeated sightings of Japanese forces, overdependence on obviously inadequate radar, inefficient communications, and insufficient aerial reconnaissance. Hepburn also cited the departure of the carriers as an inexcusable action that made it impossible to strike back at the withdrawing enemy.

The chief—indeed only—scapegoat for the Savo Island debacle was Chicago’s captain, Howard Bode. After Crutchley’s departure the evening before the battle, Bode was left in charge of the southern cruiser group. Rather than position Chicago at the head of the line of warships as was customary for an element’s command ship, Bode left Chicago behind Canberra. He wanted to avoid tricky nighttime maneuvering, and nobody had bothered to tell him Crutchley would not be returning. By not being at the head of the line, Bode was unable to effectively command his cruisers when the shooting started. Hepburn also castigated Bode for maintaining a static position west of Savo Island after the fighting moved southward and for broadcasting no radio reports of the developing attack.

After Hepburn concluded his investigation and submitted his findings to Admiral Nimitz, Bode’s mistakes became public knowledge. Unwilling to face court-martial, Bode committed suicide in April 1943 while billeted in Panama. He was, in a way, the last casualty of the Battle of Savo Island.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments