By Christopher Miskimon

The Japanese attacked the Australians near the remote village of Kokoda in New Guinea in the middle of the night on July 29, 1942. Four hundred soldiers rushed forward shouting and chanting slogans as they surged forward towards the Australians who were entrenched atop an escarpment that contained a small airfield.

Defending that escarpment were 77 men of B Company, 39th Battalion of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF). Crouching in rifle pits and machine-gun nests, they opened fire on the Japanese with automatic weapons and hurled hand grenades at the shadowy figures in the inky darkness of the jungle night.

With so few troops, the Australians could not mount an effective defense. The Japanese, well-trained in such attacks, quickly closed the distance. An Australian officer shouted for help from the troops next to him, but the only response to his voice came from the enemy, who tossed grenades in the direction of his voice. Men fought hand-to-hand with bayonets, rifle butts, and fists.

The attackers had little intelligence on the Australian position but relied on aggressiveness and training to carry through. “No one knew there was a hill,” recalled Japanese Sergeant Imanishi Sadaharu. “We knew nothing of the terrain, but we were very good at executing night attacks. We had experience of this in China. We kept shooting all night.”

Lieutenant Colonel William Owen commanded the scratch Australian force at Kokoda. Instead of remaining at the Australian base at Port Moresby, he had come forward to the front line to oversee a blocking force designed to slow the Japanese advance from New Guinea’s northern shore. The Australian position was barely set up when the attack came. In the confused fighting that night, a bullet struck Owen in the head, toppling him into a rifle pit. Captain Geoffrey Vernon, Owen’s medical officer, came down the slope with stretcher bearers to get him. They discovered the wounded officer babbling incoherently and extracted him.

One of the men helping Vernon was Jack Wilkinson. “The Japs were moving and whispering in the grass,” Wilkinson wrote. Wilkinson noted that part of Owen’s brain was protruding from his wound. “[It was] a hopeless case,” he said.

They took Owen to a hut set up as an aid station. Wilkinson held a lantern for Vernon to operate by, but each time he showed it, machine-gun fire lashed the hut. They made Owen as comfortable as they could, but he only survived another 15 minutes.

As the Japanese pressed their attack, Vernon realized it was time to retreat. He stuffed his pockets with his instruments and some field dressings and went out into the rubber trees to make his escape in the confusion and darkness. As the Australians withdrew towards Deniki, a village higher up the Kokoda Trail to the south, Vernon remained with them in order to help both wounded and stragglers.

The Australians managed to take most of their weapons with them, although the Japanese did capture five automatic weapons, 180 grenades, and rifle ammunition. The Japanese considered the Australians to be skilled marksmen and expert grenade throwers. They also noted that the Australians had greater fighting spirit than the British, Filipinos, or Americans.

Several officers urged Vernon to join them, but he stayed behind. One of the last soldiers out was Private Snowy Parr, a Bren gunner only recently trained on his weapon. Owen’s death filled Parr with rage. The Bren gunner hid at the edge of Kokoda until he saw a group of two dozen Japanese celebrating their victory in the misty dawn. When they were within 60 yards, Parr emptied a 30-round magazine into the closely packed group. He succeeded in killing 20 Japanese. Parr hastily moved back through the town’s rubber plantation to join the retreat. Vernon followed, the last man out of the village.

Six Australians died in the fight and five were wounded. As for the Japanese, they suffered 95 casualties. The Japanese greatly overestimated the Australian force. They believed they had faced as many as 1,200 Australians, but the actual number was 77.

The Australians, who were for the most part untrained militia with no combat experience, performed well, but they subsequently became demoralized at the loss of their commander. It was the first major clash of the Kokoda Trail, and it started the Australians on their way to becoming hardened veterans. More fighting lay ahead in the days to come.

The Kokoda Trail Campaign is arguably Australia’s most famous battle of the Pacific Theater of World War II. The fighting proved to be unrelenting and bitter, and neither side gave any quarter.

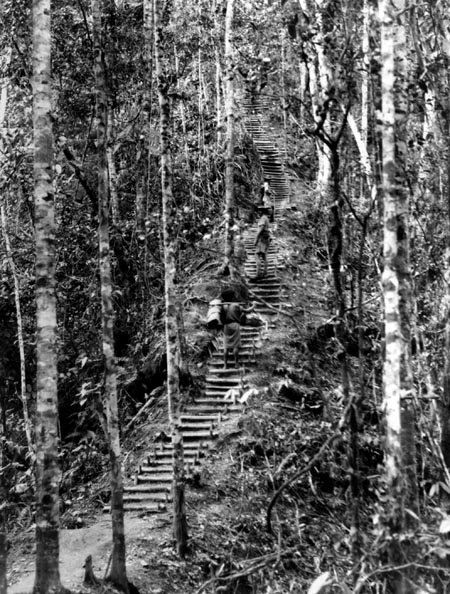

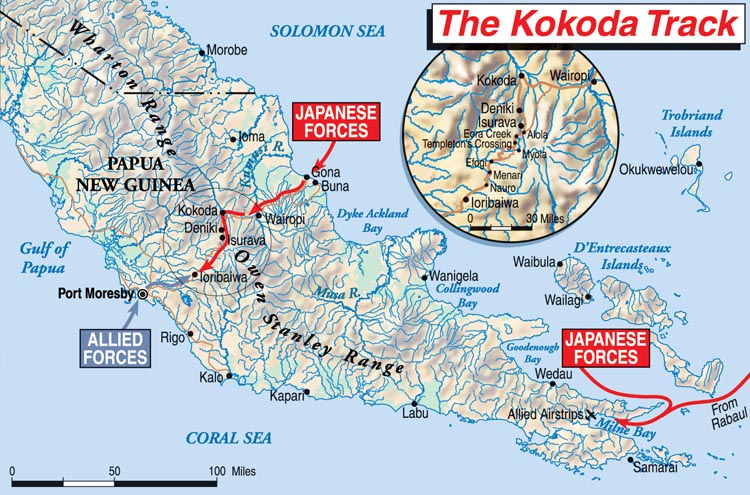

The fighting occurred on or near the Kokoda Trail itself because the jungle on each side of it was practically impenetrable. The trail led overland from the north shore of New Guinea south over the difficult Owen Stanley Mountains to Port Moresby, a vital base needed to protect the Australian mainland from attack. If the Japanese captured Port Moresby, they could use its airfields to launch air attacks against Northern Australia. Moreover, they might even be able to use it as a springboard for an invasion of Australia.

The Japanese were spread thin by mid-1942 and were not capable of carrying out a major landing in Australia, but the Allies did not know that at the time. With their plans for capturing Port Moresby dashed in the wake of their defeat in the Battle of the Coral Sea in May, the Imperial Japanese Army command decided to land its invasion force at the villages of Gona and Buna on the northeast coast of New Guinea on July 21, 1942.

This 6,000-strong invasion force, called the South Seas Detachment, was built around the 3,500-man 144th Infantry Regiment of Maj. Gen. Tomitaro Horii’s 55th Division. The regiment, which had been raised in Kochi City, Japan, had undergone extensive training for amphibious warfare. The 114th Regiment included artillery, engineer, supply, and antiaircraft detachments to support the foot soldiers.

The first wave ashore numbered 2,000 men. Horii, who led the detachment, sent an advance force up the trail to scout the route. Making their way up the trail, the Japanese ran headlong into a small Australian patrol. After a brief skirmish, the Australians fell back with the Japanese in pursuit.

This led to the attack against Owen’s small force at Kokoda. Drawn from the 39th Battalion, the force was a militia unit. The defense of the Kokoda Trail initially fell to untrained, poorly equipped reservists in this and other, similar units. Their job was to hold their own against some of the best troops of the Imperial Japanese Army.

It was all that Australia could muster to reinforce New Guinea in early 1942, because the regulars of the Australian Imperial Force had shipped out to other locations. Australian regular forces were not only fighting in North Africa, but were also fighting in Singapore and other locations in the Pacific Theater. Although Australia demanded the return of its soldiers from the European Theater once the war in the Pacific heated up, it took a fair amount of time for these troops to return from those locations. Furthermore, Great Britain was reluctant to lose these experienced troops at a time when the mother country and the vital Middle East were under considerable threat.

The militia forces were sorely short of critical weapons and equipment. Indeed, they were often held in contempt. The common nickname for militia was “choco.” A choco was a chocolate soldier who would melt away in battle. It was an unfair term that did not take into account the disadvantages they faced. When Port Moresby became threatened in mid-1942, the Australian armed forces dispatched the 39th Battalion on the grounds that Papua and New Guinea were regarded as Australian-mandated territory.

The facilities at Port Moresby were ill-suited to house and support so many troops, and the soldiers of the 39th found it rough going on New Guinea’s south coast. Nevertheless, the officers and men of the battalion did their best to prepare for the coming fight. At the outset, Owens had begun pushing troops north toward Kokoda when he learned of the Japanese landings. Due to a lack of transport, engineers, and aircraft, though, it was difficult for Owens to deploy more than a scratch force before the fateful battle at Kokoda on July 29.

After Owens’ death, Lt. Col. Alan Cameron took command, receiving orders to retake the town of Kokoda quickly. He set about laying telegraph wire up the trail from Port Moresby and developing Deniki village into a base camp, which boosted the morale of the 39th. Another officer found a small plateau in the mountains where airdrops could be carried out. This enabled Cameron to quickly plan an attack on Kokoda.

Unfortunately, the plan involved little more than a straightforward advance down the trail to the town, coupled with an ambush set for the Japanese and an infiltration into Kokoda itself. His subordinates, Captain Noel Symington and Captain Maxwell Bidstrup, protested, for they were deeply concerned that the Japanese would anticipate such a move and set a trap for the Australians. Owen overruled them, and the attack went forward at 6:30 AM on August 8.

It started badly, just as the two captains had feared. The Australians took fire from a Japanese mountain gun on the eastern slope of the valley leading to Kokoda. Bidstrup’s ambush detachment failed, surrounded by superior enemy numbers. One of its platoons became lost in the jungle for several days. When the commander of one Australian unit died at the hands of a sniper, his men were so enraged they charged straight down the valley. The defending Japanese were so shocked by this move that they fell back in disarray.

Symington had more success. His men crept down the mountain, went into Kokoda through the rubber trees and found it practically unoccupied. The Japanese commander, Lt. Col. Tsukamoto Hatsuo, did not expect such a move against Kokoda and had sent his troops ahead to outflank the Australians. The Australians surprised the small group of Japanese left to guard the airstrip and sent them screaming into the jungle. They also captured a notebook with details and a map of the Kokoda Trail. Sergeant Major Jim Cowey signaled their success by firing a flare into the sky as ordered, but tragically, no one back at Deniki saw the signal, even though they were supposed to be watching for it. Assuming reinforcements were on the way, Cowey put his men into the battalion’s trenches from the first battle and prepared to fight the Japanese as dusk fell.

Tsukamoto, stung by the loss of Kokoda, immediately prepared a counterattack. It went in at 11:30 AM the next morning. Japanese troops, their uniforms covered in vegetation and their faces smeared with mud, crept forward in a driving rain. Machine-gun fire cut into them, felling many and forcing the survivors to pull back. Symington had wasted no time spreading automatic weapons across his line of defense. A second attack at dusk also failed. Two more assaults unfolded over the course of the night.

This proved a psychological blow to the Japanese, who were unused to repeated failures. Some of the night fighting was hand-to-hand. A Japanese corporal killed one man with a bayonet before being forced back. As one of his comrades struggled with an Australian, the corporal threw a grenade and wounded the Australian soldier. At dawn, the Japanese withdrew a short distance and prepared a coordinated attack for the following sunset.

That attack began with the trading of insults between the two lines. The Japanese lit smoke candles at the edge of the jungle, then charged through the clouds screaming. Some of their troops fired knee mortars, which were akin to a modern grenade launcher, as the range closed to 70 yards. Australian fire greeted them for a time, and then slackened. The Japanese sprinted the remaining distance, ready to close and kill their enemies, but there was no one there. Symington’s troops, outnumbered and out of ammunition, had quietly and cleverly broken contact. His men withdrew back to Deniki. Eighty Australians had managed to hold off 400 Japanese for three days. The Australians lost 20 men in that effort. The lack of reinforcement and poor logistics took its toll, though. Kokoda was now back in Japanese hands.

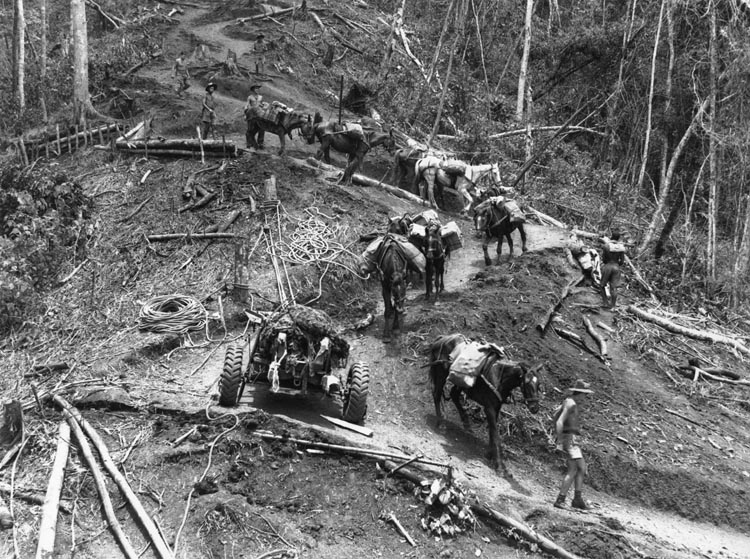

Momentum and numbers favored the Japanese as their advancing front continued to push the Australians inexorably south toward Port Moresby. The trail was difficult, the jungle environment hostile, and supplies running low. Natives worked as carriers, trekking up and down the arduous track, with heavy loads of food and ammunition going forward and wounded men on the way back. The Australians could never have sustained themselves without the labor of these locals. With every grueling step backward, the Australians came closer to their own supply sources, while the Japanese drew farther away from theirs with each passing day. Initially, the Japanese maintained their pace, but food shortages were already affecting both sides. This situation worsened in the weeks that followed.

As Australian militiamen performed their gallant fighting retreat, Australian regulars finally began arriving in Port Moresby. Brigadier General Arnold Potts’ 21st Brigade of Maj. Gen. Arthur Allen’s 7th Division disembarked. Potts’ superior officer as commander of the New Guinea Force was Lt. Gen. Sydney Rowell, a veteran of Greece and the Middle East. Rowell’s superiors nudged him on a daily basis to switch to the offensive. The first task he undertook was to improve the logistical situation. Only by doing so could his troops hope to commence offensive operations.

The 3,000 men of the newly arrived brigade prepared to move up the trail and relieve the 39th. Accompanying them was the 53rd Battalion, another militia unit. As Potts and his men moved up the trail, they ran into wounded men of the 39th coming back; they were emaciated, their uniforms in tatters. The natives, who treated them like brothers, often carried the wounded and exhausted Australians. It was a sobering sight for the 21st despite their combat experience. Potts soon realized the true difficulty of the supply situation and urgently requested airdrops, but the supply situation remained frustrating.

The next major fight along the trail occurred at Isurava. Six thousand Japanese troops attacked 1,800 Australians, 1,200 of whom were newly arrived veterans. Despite food shortages, Japanese morale remained high, as shown by Japanese diaries. “I will die at the foot of the Emperor!” wrote Lieutenant Kogoro Hirano wrote in his diary. “Advance with this burning feeling and even the demons will flee!”

Horii reconnoitered the Australian positions on August 24 and formulated his plan. He intended to encircle the Australians from both east and west. The following day, an Australian patrol from the 53rd skirmished with the Japanese and held their own, but more assaults were coming. At dawn the next day, flanking Japanese columns struck while another group came straight down the trail. Machine guns chattered across the valley, and the Japanese were supported by a mountain gun that shelled the Australians. Patrols hunted the Japanese in the tall grass around the area until dusk.

That night, the enemy struck two platoons of the 39th just a few hundred yards outside the village, cutting them off and mauling them in close combat. The survivors fell back to Isurava, where they met the first men arriving from the 21st Brigade. The haggard militiamen asked who the new men were. The reinforcements announced that they belonged to 2/14th Battalion of the Australian Imperial Force. The militiamen, dressed in rags and debilitated by disease, were overjoyed to see reinforcements at last. The regulars were impressed. Despite all they had endured, the militiamen of the 39th were still in the fight.

The next day, though, the 53rd met with disaster. As its soldiers advanced to retake a small village, 200 men of the battalion ran into Japanese patrols. Someone panicked, and the panic spread; the unit scattered with many casualties. When the battalion commander lost contact with his companies, he led a party forward and walked into an ambush, the first to die. Potts called forward the 2/16th Battalion and sent the remaining men of the 53rd back to Port Moresby. Meanwhile, the Japanese renewed their assault with the support of mountain guns and mortars. The Australians had not managed to get any artillery forward, so they had no way to reply.

“Mortar bombs and mountain gun shells burst among the tree tops or slashed through to the quaking earth, where the thunder of their explosion was magnified in the close confines of the jungle thickets,” wrote Lt. Col. Ralph Honner of the 39th Battalion. “Heavy machine guns … chopped through the trees, cleaving their own lanes of fire … bombs and bullets crashed and rattled in an unceasing clamor that re-echoed from the affrighted hills.”

The fighting continued through the night, with bayonets a primary weapon. One Japanese soldier made a lasso from vines and looped it around an Australian’s ankle. The Australian soldier fought back as he was dragged into the jungle. He drew his bayonet, stabbed his captor through the eye, cut the vine, and escaped.

The Japanese shouted and banged on mess tins to keep their opponents awake all night. Despite heavy casualties, the Japanese came back the next day, assailing the Australian positions. Bren gunners soon had piles of enemy dead in front of them, but the attack continued until it was hand-to-hand. Honner described in vivid detail the ferocious nature of the fighting: “But still they came to close with the buffet of fist and boot and rifle butt, the steel of crashing helmets and of straining, strangling fingers,” he wrote.

By the morning of August 30, the relentless Japanese attacks forced the Australians to withdraw down the trail, fighting as they went. 2/14th Battalion’s headquarters was threatened at one point. In another incident, Private Bruce Kingsbury joined another platoon after his own was decimated. He counterattacked the Japanese, firing his Bren gun from the hip, despite machine-gun fire snapping around him. Kingsbury cleared a path through the enemy and then assaulted their positions, inflicting multiple casualties before a sniper’s bullet cut him down, killing him instantly. His valorous action stabilized the Australian position and prevented a breakthrough, securing for him a posthumous award of the Victoria Cross. It was the first such award made for actions in defense of Australian territory.

As the Australians fell back further, another soldier displayed selfless courage. Corporal Charlie McCallum remained behind to cover his platoon as they withdrew, firing his Bren gun into the charging Japanese. When he ran out of ammunition, he grabbed a Tommy gun from a dead friend and kept shooting with one hand while reloading his Bren with the other. The Tommy gun went empty, and McCallum returned to his Bren. The Japanese were all around him now, and he was wounded three times. One fatally wounded enemy lunged at McCallum as he died and ripped the utility pouch from his uniform. After killing 25 Japanese, the corporal fell back. He later perished in another firefight along the trail and was posthumously awarded a Distinguished Conduct Medal.

It rained solidly for the next three days. The Australians tried their best to evacuate their wounded while still holding off the advancing Japanese, who continued their relentless assaults. The two sides laid ambushes for each other, and close-quarter fighting occurred frequently. After a time, Japanese discipline began to break down; officers had to threaten with their swords to get their soldiers moving. Australian patrols would find the Japanese and hit their lead troops before falling back; with the enemy located, the Australian main body would then conduct a pincer attack against the enemy flank. Afterwards, the strike force would fall back and prepare to do the same thing again. The Australians occasionally left spoiled cans of bully beef in the open as bait for the hungry Japanese; when a group of starving Japanese soldiers rushed to get it, Australian snipers would cut them down.

In early September, the fighting focused around Brigade Hill and nearby Mission Ridge, where one Japanese force attacked frontally while another made a long flanking maneuver from the west and managed to take up a position behind most of the Australian troops.

The flanking force, a company led by Lieutenant Mitsuri Sakamoto, spent 11 hours climbing a 45-degree hillside dragging a machine gun behind them. They occupied a point between Brigadier Potts’ headquarters and the rearguard of the 2/16 Battalion. Potts was returning from the latrine when a nearby sentry fell, shot through the head. The Japanese machine gun opened up, and Sakamoto’s company attacked both the Australian HQ and rearguard positions at once.

The headquarters troops grabbed rifles and revolvers, engaging their enemy from 15 yards, but machine-gun fire drove them back. Sakamoto ordered the Australian field telephone lines cut, but Potts had a working radio and called for help from the battalions situated to the north. Three companies of Australian infantry came back down the trail to dislodge the Japanese, but the machine gun cut down dozens of men packed onto the narrow trail. The Japanese who were attacking to the north increased their pressure, compelling the Australians to divert into the jungle around Sakamoto’s position and continue withdrawing down the trail. Sakamoto’s reward was a plate of rice, the first he had consumed in three days. He and his men resumed the pursuit the following day.

After the debacle at Brigade Hill, the Australians made a stand at Ioribaiwa Ridge in mid-September. As they had previously done, they set out cans of bully beef along the banks of a creek to entice the Japanse to leave their cover. Forty Japanese appeared to retrieve them, and the Bren gunners fired, killing half of them. The angry Japanese launched an attack in revenge, charging uphill in a lashing thunderstorm against the Australians, who held the high ground on a ridge. The assault failed miserably; Sakamoto recalled seeing an entire platoon wiped out.

The remaining Japanese found a patch of high ground unnoted on Australian maps. From there, they fired down onto Australian trenches, many of them only half-completed. The local commander, Brig. Gen. Ken Eather, asked for permission to withdraw to Imita Ridge, just a little farther down the trail. Major General Allen granted him permission to do so, even though the position was just 25 miles north of Port Moresby. Allen was adamant that there could be no further retreat after that. “You’ll die there, if necessary,” he told Eather. “You understand that?” Eather acknowledged the order.

Meanwhile, Japanese troops occupied Ioribaiwa, elated to see the lights of Port Moresby in the distance. The hungry, long-suffering troops considered the sight as nearly tantamount to success. If they could capture Port Moresby, they would be able to eat and drink their fill from captured rations and celebrate the victory they had fought so hard to achieve. More than 1,000 Japanese soldiers had died by that point, and another 3,000 were wounded and sick. This left approximately 1,500 remaining.

The starving soldiers were heartened to see their final objective within reach, but they did not know that Horii already had orders to begin a disciplined withdrawal. The Imperial Japanese Army command had ordered the withdrawal because it lacked sufficient forces to reinforce those engaged on New Guinea and Guadalcanal at the same time.

The Japanese wandered through the abandoned Australian dugouts in a desperate quest for hastily discarded food. The Aussies had left fragments of biscuits and spoiled cans of bully beef. They had booby-trapped most of the leftovers. Some of the Japanese were desperate enough to try eating what they found. Not surprisingly, they became seriously ill.

Horii implored his men to retain their martial spirit, reminding them of all they had accomplished. He even sent troops to scout Port Moresby for a final assault, even though he’d already received orders to retreat.

On the morning of September 15, one of these reconnaissance patrols walked into an ambush set by the 2/33rd Battalion. The Australians lay hidden in tall grass, watching as upwards of 70 Japanese walked right towards them. The Japanese were bunched together in two lines, carrying canned food they must have found somewhere. They were led by an officer carrying a sword. The entire group acted more like they were out for a leisurely stroll than fighting in a combat zone. Perhaps the food they were carrying excited them, causing the hungry men to lose their discipline. Whatever the case, they were about to walk into a lethal trap.

Captain Larry Miller initiated the ambush by shooting the officer. Upon this signal, his men opened fire. Rifles cracked, sub-machine guns chattered, and mortar shells crashed into the ground. The shooting lasted for about two minutes. The Australians fired approximately 3,000 rounds into the densely packed group. The wounded lay scattered on the ground, screaming and helpless. After planting booby traps on the trail, the Australians fell back, leaving the bloody scene. That was the last of the Japanese probes.

While the Japanese starved and contemplated retreat, the Australians busily prepared a counterattack. They dragged a field gun up the trail, moved it into position, and stacked ammunition next to it. The gun crew opened fire on September 25, pounding the no-man’s-land in the valley between the opposing lines. Even though the shells fell short, the Aussies cheered each blast. At long last, they had artillery. The Australians scheduled their counteroffensive for September 27, with three battalions moving across the valley on September 26 to get into position for the pending attack.

That same day, the exhausted Japanese formed up and began the march back north. Many were humiliated at this development, for they had never lost before. Others, though, seemed glad to be leaving. Many of the wounded were left behind—shot or ordered to commit suicide. A few made it only a small distance before collapsing by the side of the trail.

At mid-morning on September 27, the two leading Australian companies climbed the Ioribaiwa ridge, straight into the abandoned Japanese camps. A few soldiers admired a large set of observation binoculars, mounted on a tripod. Gazing through it, they saw their former positions on the opposite side of the valley.

The counterattack was now a pursuit. The lead troops moved through scenes of prior fighting, finding the bodies of comrades lying yet unburied. Six Australian bodies lay in stretchers, each corpse showing bullet or bayonet wounds from their executions. Some remains lay where they fell, fingers still on the triggers of their weapons. Dead native carriers dotted the area, too, worked to death or executed by the Japanese for failing to keep up. These corpses were otherwise untouched, but as starvation had ravaged the retreating Japanese, they’d butchered dead Australians for food.

The Japanese stopped and entrenched at Templeton’s Crossing in October. The crossing consisted of a single log that constituted a bridge over Eora Creek. Jungle canopy covered the area, keeping it perpetually dark. They emplaced machine guns along 600 yards of the trail in camouflaged log bunkers. They were so well hidden that on October 11, the first Australian patrol walked right up to them and straight into an ambush. The Aussies planned a two-battalion attack for the next morning, determined to maintain their momentum and keep the Japanese rolling back.

The attackers set off at 8:00 AM. Approximately 200 troops participated in the attack, approaching the Japanese from both flanks. There were no maps, and visibility was measurable in mere feet. Captain Tim Clowes led one of the flanking forces. His troops reached a final ridge and ascended the steep slope on hands and knees.

At the top, they ran headlong into a Japanese headquarters just 20 yards away, surprising both sides. The Australians charged, and the Japanese responded with grenades and machine guns. Clowe’s men were forced back to a ravine 70 yards away, where they dug in. Other Australian positions nearby assailed the line of machine-gun nests. The fighting became point-blank, with a few men getting right up to the bunkers to throw grenades into the firing slits. Those Japanese not killed fled out the back doors, but were cut down. The bunkers covered each other, and the soldiers in the remaining bunkers kept the Australians at bay. The battle ended in stalemate, and the two sides dug in just yards from each other. In these positions, the opposing sides spent the next few days sniping at each other.

It took two days to slowly dislodge the Japanese from their gun pits as patrols flanked them from the rear. On October 13, approximately 50 Australians crept up on a Japanese encampment and caught them unawares. The Bren gunners cut down 30 of them as they fled. In other places, Japanese shouted orders in English, trying to confuse and trap their enemy. The Australians, recently arrived from the Middle East, began speaking Arabic. The defeated Japanese retreated again, this time with their pursuers close behind.

The next line of defense for the harried, starving Japanese came across Eora Creek. The waterway flowed through a gorge with muddy, jungle-covered slopes and a high ridge overlooking it. A pair of log bridges crossed it, enabling a small number of troops to mount a strong defense. They set up machine guns in log bunkers and awaited the Australians of the 16th Brigade, rotated into the lead position. Brigadier General John split his force in order to encircle the enemy, with some of the troops having to cross log bridges to get into position.

The attack did not go well. The flanking force took longer than expected to get into position because of the rough terrain. Two of its three platoons got lost, leaving only 17 men for the assault, which went ahead anyway. After stealthily approaching a small Japanese camp, they charged the site, spraying it with gunfire. The Japanese counterattack surrounded this Australian force and nearly wiped it out; only four Australians survived.

Meanwhile, the force crossing the log bridges set out under cover of night. As they approached with great stealth, they encountered enemy machine-gun positions. Two forward scouts found the Japanese asleep at their machine guns, so the lead company tried to cross before the enemy was alerted.

Most of the company got over before the Japanese machine gunners awoke to the threat and opened fire. The last few men dashed over the span as bullets cracked around them, but the group got bunched up on the north side. The Australians found several trails that led off in different directions, but they could not tell where they led in the darkness. Some of the men followed one of the trails, only to find that it was a dead end with a sheer cliff on one side. The Japanese proceeded to drop grenades down on them from the cliff. Lance Corporal John Hunt scaled the cliff, hunted the Japanese grenade throwers, and shot them.

Another group of 100 Australians followed Captain Basil Catterns up the ridge straight at their enemy. Heavy fire tore into them as they dug in 30 yards from the Japanese. They scraped out shallow fighting positions using their helmets as shovels. The Australians remained pinned down in the positions for an entire week. They held firm, despite repeated attempts by the Japanese to kill them by rolling grenades down the slope at their positions. The Japanese also fired mortars at their positions, but most of the shells turned out to be duds. Having the high ground, the Japanese grimly held on. Horii toasted his men with sake as they fought the Australians to a standstill.

To break the stalemate, Colonel Paul Cullen launched a battalion-sized attack. Major Ian Hutchison’s 2/3rd Battalion formed into three columns of 200 men each and swept aside the enemy. The Australians fired from the hip as they dashed from tree to tree. It proved too much for the ill and exhausted Japanese. They withdrew in the face of the large-scale assault.

Corporal Lester “Tarzan” Pett ran from one Japanese bunker to the next and hurled grenades through the embrasures. He destroyed four by himself, earning a Military Medal, though he would die in action two weeks later. With the enemy retreating, those Australians stuck on the slopes pushed forward to find their opponents gone. The next day, September 29, the attackers reached the Japanese camp, where they found 69 dead bodies and a number of maps and documents.

As the troops slogged slowly forward, a new division commander arrived, Major General “Bloody George” Vasey, who had earned his nickname as a result of his penchant for swearing. Vasey believed in leading from the front and speaking plainly, which soon endeared him to his men. He admonished them to patrol constantly to avoid the favored Japanese tactic of encirclement.

Vasey accompanied his 16th Brigade as it advanced on the village of Alola. The Australians took possession of the village unopposed. Vasey established his headquarters in the village and began plotting his advance on the village of Kokoda. As a division commander, he purposely set up his command operation forward of the brigade-commander’s headquarters. This tactic shamed his subordinate into moving his staff ahead, a tactic Vasey claimed help keep his force on the attack. At that point, Kokoda lay just a half day’s march ahead.

Horii still held out hope that he might achieve victory, for in late October, he received word that a fresh division of 20,000 troops was expected to land. Morale soared, only to plummet when most of that division was redirected to Guadalcanal as the fighting there took a turn for the worse. From an initial strength of 6,000, the brigade-sized South Seas Detachment of the Japanese Imperial Army had less than 1,000 men fit for combat by autumn. One battalion had only 16 able men. Horii continued to exhort his remaining men to continue fighting.

An Australian patrol entered Kokoda on November 1, only to find it abandoned, as well. Three months after the Japanese drove out the scratch force of militiamen, the Australians were back in force, spreading out across the plateau and retaking the airfield. The Australians put the natives to work clearing growth from a landing strip that the Japanese had never used. Within two days, planes brought in fresh supplies, renewing the Australians for the task of pursuing the Japanese up to Buna and Gona. The Americans were also scheduled to go into action to assist the Australians in the final push to drive the Japanese into the sea.

Horii anchored the Japanese defense on the villages of Oivi and Gorari. Their backs faced the Kumusi River seven miles away. If they were forced to retreat, they faced a difficult river crossing. The Japanese set to work preparing defenses that faced west and south, building dugout fighting positions fortified with palm logs. Their line of defense was three miles long and one mile wide. Oivi sat on high ground on the west end with Gorari a mile east, linked by the trail.

Vasey now ordered the largest land attack an Allied commander had yet made in the Pacific War. Seven Australian battalions deployed, with no reserve. It was a risky plan, but Vasey wanted to maintain his momentum. The 16th Brigade advanced toward Oivi, while the 25th Brigade moved along a parallel trail towards Gorari in order to outflank the Japanese from the south. The Australians brought up mortars to strike the Japanese on November 7. The mortar barrage was strengthened by an aerial bombardment furnished by American bombers. An infantry attack followed the mortar barrage, but it failed, costing Vasey 47 men.

The next morning, American fighters strafed and bombed the Japanese bunkers, while the 25th Brigade, having moved too far, retraced its steps to move into the attack. Patrols skirmished with heavy losses to both sides. The Japanese realized they were outflanked and reinforced their lines, but the Australian attack was gaining momentum. The defenders at Oivi were soon cut off from those at Gorari, unable to break through a line of Australian machine guns set up to stop them.

The Japanese brought up a 75mm mountain gun at the village of Gorari in order to blast through the Australian lines, shelling the 2/33rd Battalion for three hours. When a few Australians tried to retreat, their commanding officer forced them back to their positions with his revolver. The Australians held on and kept the Japanese bottled up. By November 11, they were ready to finish the job. The night was moonless, but a torrential rain soaked the combatants on both sides. Australians crept through the tall grass toward Gorari, surrounding it as a detachment moved around to the north.

Without warning, hundreds of Japanese suddenly charged. It was a desperate attempt to break out of the encirclement. Sword-waving officers charged Australian machine guns, only to be cut down. Grenades exploded among the charging forms of Japanese troops running through the darkness. Hand-to-hand fighting broke out all along the battle line. The injured lay in the mud awaiting help as men from both sides became helplessly confused and mixed together. When the combat died down, the cries of the wounded punctuated the night, together with occasional shots when probes collided in the darkness.

At midnight, a blood-curdling scream startled a dug-in Australian platoon as a Japanese soldier appeared their midst and tried to bayonet Private “Yippee” Bowen. The unusually strong Bowen grabbed the rifle from his attacker’s hands. As the man tried to flee, Bowen hurled the bayoneted rifle like a spear into his back.

Fighting continued the next morning, when the desperate Japanese charged the Australian machine-gun positions. Corporal St. George Ryder was changing the magazine on his Bren gun when an enemy officer attacked with a sword, knocking off his helmet and slashing him across the face. The corporal slammed his knee into his opponent’s groin and they both fell to the ground, wrestling until another Australian killed the officer.

When the battle ended, 580 Japanese bodies littered the area. The survivors made haste to reach the Kumusi River; it was a pitiful retreat. Most of the wounded were left behind. The Japanese either buried or simply abandoned their few remaining field guns. They then lashed together palm logs to make rafts for crossing the river. Some made it across, clinging to rafts loaded with their weapons or wounded soldiers, but many drowned in the swift-flowing waters, as the river was at flood stage.

Horii crossed on a raft, which broke up on the far bank, but he found a canoe and floated it to the mouth of the river. From there, he apparently tried to paddle it along the coast, but a gale blew the canoe out to sea. Horii and his orderly abandoned the canoe and tried to swim to shore. Horii drowned, but his orderly survived. He initially concealed the news of Horii’s death to preserve morale, but the surviving troops soon learned of their leader’s fate.

The Japanese fell back toward Gona and Buna, where the Australians were joined by American troops for the final actions. By January 1943, Australian and American troops had succeeded in prying the Japanese from the last of their fortified beachheads. The Australians suffered approximately 2,100 killed and wounded, and the Japanese lost 12,000 dead.

The struggle for the Kokoda Trail and to preserve Port Moresby was almost entirely an Australian endeavor. The Australian militia and regulars made a supreme effort and sacrificed under terrible conditions. Thousands fell on each side, killed, wounded, or sickened by tropical disease and hunger in one of the most grueling encounters of the entire war.