By Joshua Shepherd

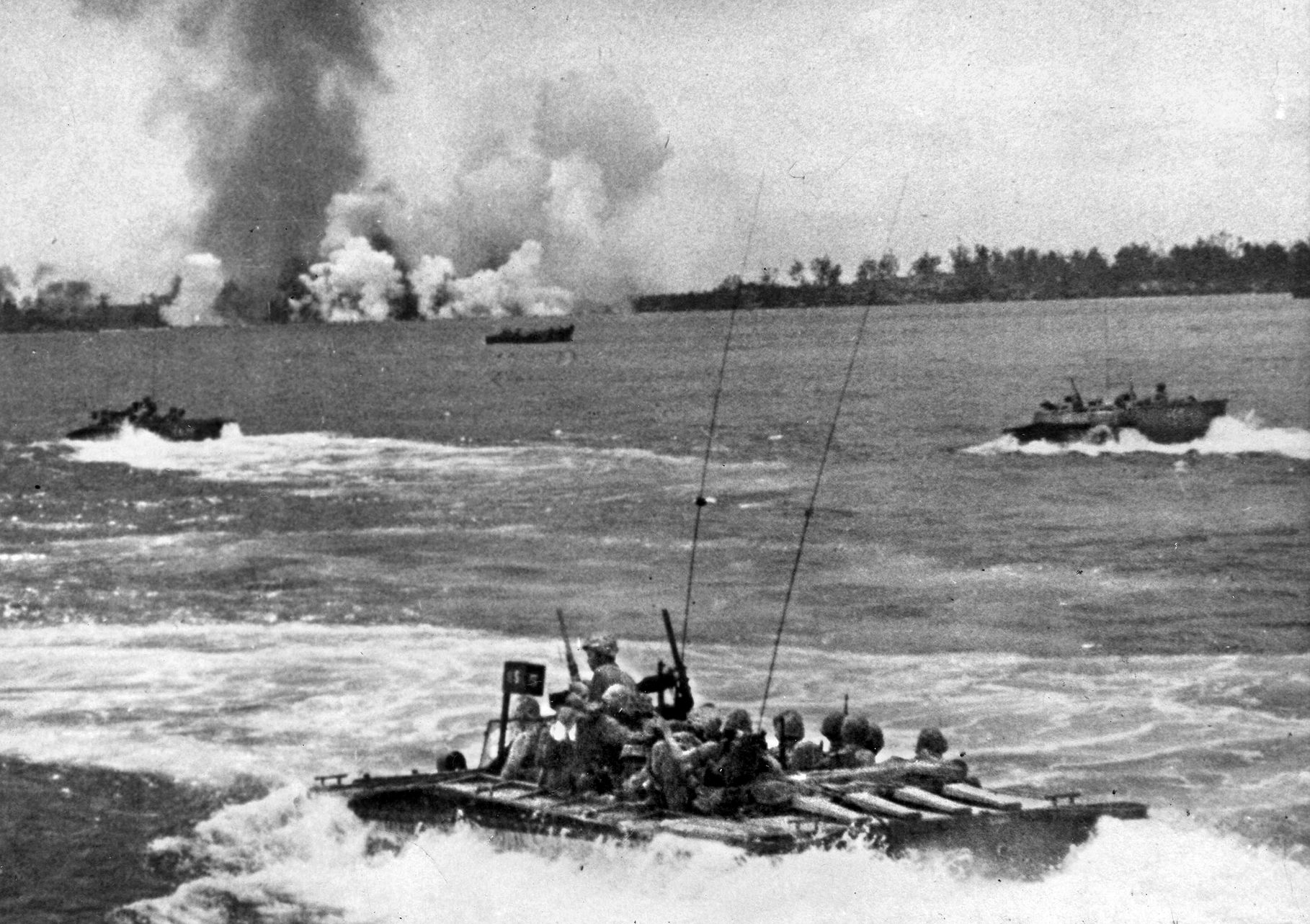

Amphibious landing craft carrying U.S. Marines plunged through heavy surf toward the beaches of Peleliu Island, a formerly inconspicuous tropical paradise in the Palau Islands.

Colonel Lewis B. Puller, affectionately known as “Chesty” to the men of the 1st Marine Regiment, was aboard an Amtrac in the first wave of troops that would hit the beach on the morning of September 15, 1944. A highly decorated veteran who had been in the Corps for a quarter century, Puller was renowned as a front-line commander who led by example.

But as his Amtrac struck the beach, even Puller was aghast at what his men faced. A hurricane of enemy machine gun fire rent the air, crashing into the Amtrac and bowling over Marines up and down the landing zone. “I went up and over that side as fast as I could scramble and ran like hell at least twenty-five yards before I hit the beach flat down,” he recalled.

Puller had never seen hotter fire in his life. Glancing over his shoulder, he watched in horror as the Amtrac he had just left was hit by a shell and obliterated in an orange fireball. As his men fell around him, it was apparent to Puller that the Marines had entered what he described as a “whirlwind of machine gun and antitank fire.”

The grueling battle that would unfold at Peleliu had ironically been borne of American success. By summer 1944, the tide of the war in the Pacific had clearly turned against the once-vaunted Japanese Empire. On New Britain and New Guinea, Japanese forces were on their heels in the wake of successful Allied campaigns. In February the Americans had largely neutralized the vital Japanese naval base at Truk in the Caroline Islands. During the summer American forces had seized the Mariana Islands, affording the Army an ideal base from which to launch strikes with B-29 Superfortress heavy bombers directly on the Japanese homeland.

The stage had been set for a knockout blow against the Japanese home islands, but the precise route toward that final objective remained in dispute. General Douglas MacArthur, who had been forced to evacuate Corregidor Island in 1942, not surprisingly favored an invasion of the Philippines, followed by the seizure of Okinawa. For his part, Admiral Chester Nimitz considered the Philippines as a nonessential target, and advocated for an invasion of Formosa and Okinawa in preparation for a direct attack on Japan. The final decision was made by President Franklin Roosevelt, who approved MacArthur’s preferred route.

But as Allied planners plotted the course toward the Philippines, they knew they would have to clear and capture the Japanese-held Palau Islands. Situated to the north of MacArthur’s proposed naval route, it was feared that Japanese aircraft operating from the Palau Islands could wreak havoc on American shipping bound for the Philippines.

Initial plans consequently called for a massive strike to eliminate the Japanese hold on the island chain. The northern islands of Babelthaup, Yap, and Ulithi were to be seized by U.S. Army Maj. Gen. John Hodges’ XXIV Corps consisting of the 7th and 96th infantry divisions. The two southern Palau islands of Peleliu and Anguar were assigned to Maj. Gen. Roy Geiger’s III Amphibious Corps, which comprised the 1st Marine Division and the Army’s 81st Infantry Division. The operation to reduce the islands was slated for mid-September 1944.

From the outset, however, the American top brass disagreed over the necessity of the entire operation. Admiral William “Bull” Halsey, commander of the 3rd Fleet, felt that the islands posed little threat to the advance on the Philippines. Fearful that the infantry would be thrown into a costly fight unnecessarily, Halsey argued that the Palaus should be bypassed entirely.

By the middle of the month, Halsey pushed hard for the entire operation to be scrapped. American aircraft had launched an offensive in a wide arc from the Palaus to the Philippines and had experienced great success in wrecking enemy airfields and aircraft. With American air superiority firmly established in the area, the need for any amphibious assault on the Palaus was increasingly in question.

Nimitz had to make one of the most difficult, and ultimately controversial, decisions of the war in the Pacific. The admiral was persuaded that the entire island chain posed little threat, and accordingly canceled the proposed landings on Babelthaup, Yap, and Ulithi. The troops scheduled to assault the southern Palaus, however, would receive no such reprieve. Anxious to seize the Japanese airfield on Peleliu and neutralize any danger to MacArthur’s right flank, Nimitz ordered the landings to proceed.

Aside from their military value, the southern Palaus were isolated and seemingly insignificant. The smaller island of Anguar, situated six miles southwest of Peleliu, was lightly defended. Peleliu, believed to be held by 11,000 Japanese troops, would be a far more difficult assignment for the leathernecks of the 1st Marine Division. The division, which had seen action at Guadalcanal and Cape Gloucester, had a solid core of veterans in its three regiments, which were the 1st, 5th, and 7th Marine Regiments.

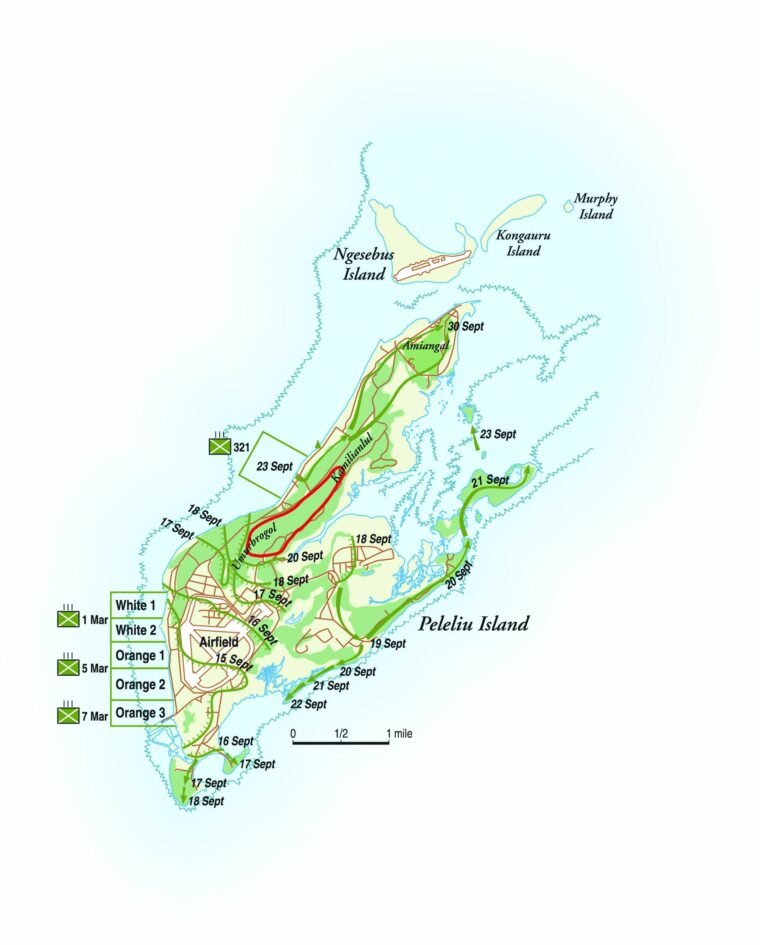

The island, which some observers thought resembled an ominously open crab claw, was surrounded by coral reef. The center of the island was dominated by forbiddingly rugged hill country, in particular the peaks and ravines of Umurbrogol Mountain. The southern half of the island was relatively flat terrain, and was occupied by a Japanese airfield. The soil of the entire island was little more than coral and limestone. For the infantrymen who would struggle for the island, digging in would be nearly impossible.

The basic plan for the attack on Peleliu, unpropitiously codenamed Stalemate II, had been honed during repeated amphibious landings across the South Pacific. Subsequent to a massive aerial and naval bombardment intended to soften up enemy positions, the division would hit the beaches in a three-regiment-wide front. To the left, the 1st Marines would come ashore just south of a rocky crag known as “The Point.” Storming up the center, and hopefully across the island toward the airfield, would be the 5th Marines. On the south, the 7th Marines would cut across the island, mop up any Japanese cut off during the assault, and secure the division’s right flank before wheeling north.

While briefing his senior officers on the coming operation, Maj. Gen. William Rupertus, commander of the 1st Marine Division, was sanguine over the prospects of success. Although he acknowledged that the division would undoubtedly suffer heavy casualties, he assured his officers that the campaign would proceed rapidly. “This is going to be a short one, a quickie, rough but fast,” Rupertus said. “We’ll be through in three days. It might take only two.”

The Japanese commander on Peleliu entertained other ideas. Direct defenses on the island were under the command of Colonel Kunio Nakagawa. The core of Nakagawa’s force was the 2nd Infantry Regiment, a crack outfit that had seen extensive service in China. Japanese defenses on the island were impressive. Nakagawa had busied his soldiers for months in constructing a forbidding mix of defensive positions, and the island’s interior was studded with a maze of concrete bunkers, pillboxes, and a labyrinth of underground tunnels. Artillery pieces, dug into the island’s coral cliffs, were well-concealed and protected by heavy steel blast doors.

Beginning on September 6, Peleliu was attacked from the air by 600 planes launched from the carriers of the American Task Force 38. For three days, the planes bombed supply dumps, warehouses, and barracks. With no Japanese planes to oppose them, the American aircraft operated with impunity. On September 10, the American planes were at it again, hitting antiaircraft emplacements and beach defenses for an additional three days.

On September 12 the U.S. Navy opened up with her big guns, unleashing a devastating bombardment intent on softening up Japanese positions. A line of battleships, including the Pennsylvania, Maryland, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Idaho, rocked the island with fire from massive 14-inch and 16-inch guns. American cruisers lent their weight to the attack, battering island defenses for two hours in a massive display of firepower.

With its bark-less trees and incinerated vegetation blanketed by black smoke, Peleliu resembled a surreal moonscape after three days of bombardment. But Japanese troops, holed up in tunnels, caves, and pillboxes, had suffered relatively light casualties. Shocked by the bombardment but retaining remarkable cohesion, the island’s defenders were itching for a fight.

They would not have long to wait. On the morning of September 15, Marines in Higgins boats began forming up among the big ships of the American fleet, waiting to be ferried to the shallow-draft, tracked Amtracs that would then take them over the reef and across the lagoon to the beaches.

On the left, the 1st Marines under Puller’s command would assault White Beaches 1 and 2. In the center, the 5th Marines of Colonel Harold “Bucky” Harris would target Orange Beaches 1 and 2. On the right, Colonel Herman Hanneken’s 7th Marines would assault a narrow strip of beach named Orange 3.

As the Amtracs plunged through the surf, an immense naval bombardment continued overhead, seemingly ripping the island apart. Inexperienced Marines who witnessed the heavy cannonade thought that the impressive gunfire would render an infantry assault a cakewalk, but veterans knew better.

From the clouds of black smoke engulfing the island, Japanese gunfire and mortar rounds began striking the lagoon. As the landing craft were slowed down crawling over the reef, pre-registered Japanese guns opened up on the vulnerable Americans.

Enemy mortar and artillery fire soon whipped the lagoon to a froth, knocking out a number of Amtracs before they could reach the sand. For Marines aboard the Amtracs, helplessly exposed to enemy fire, the approach to the island seemed an eternity. Amid a deafening storm of artillery fire and the sharp ping of machine gun fire striking the landing craft, terrified men could do little but steel their nerves for the inevitable and pray. At 8:30 a.m. the first amtracs crawled ashore at Peleliu.

Once they landed, Marines scrambled over the sides of the Amtracs before they drew fire from the island defenders. But the beach was no better than the lagoon as mortars and artillery churned the white sand, leaving it pockmarked with craters and reddened with the blood of stricken Marines. Men entering combat for the first time witnessed surreal horrors they would never forget. Struggling forward through blinding smoke, geysers of sand, and a storm of fire, they could hear little above the roar of artillery and the screams of the wounded.

On the left, the hard-pressed leathernecks of the 1st Marines were bogged down from the outset. Machine guns with interlocking fields of fire rendered the beach a veritable killing zone. As he struggled to get his men moving and make room for successive waves of troops, Puller faced the jagged, coral-encrusted Point that had been heavily fortified by the Japanese. Machine gun and mortar fire from the Point flailed Puller’s left flank, halting his forward momentum and leaving his troops dangerously pinned down.

On the right flank, the 7th Marines were being chewed up on Orange Beach 3. The narrow beach, just 550 yards wide, forced Hanneken to land just one battalion, reducing his initial landing strength. Terrified Marines lay paralyzed in the sand, easy targets for Japanese mortar crews. Amid the confusion, a lone officer coolly stalked up and down the beach shouting orders. This officer was Major Arthur Parker, Jr., the executive officer of the 3rd Amphibious Tractor Battalion. “Get the hell off this beach, or I’ll shoot your ass!” Parker thundered at the Marines.

Struggling forward, the regiment found welcome cover in the form of a six-foot-deep Japanese anti-tank ditch. Marines piled into the ditch, ecstatic that they had found a bit of safety, and officers corralled their disorganized men, regrouping them for a renewed push inland.

The 5th Marines landing on the center beaches had fared only slightly better. Although their flanks were secure, heavy fire poured in from directly in front of them from fortified concrete bunkers. The steady rattle of Japanese machine gun fire had also transformed this pristine white beach into a surreal killing field.

The regiment’s officers succeeded in herding their men forward, assaulting Japanese machine gun nests hidden in coconut groves just east of the beaches. It was a harrowing job. Heavily camouflaged Japanese positions were nearly invisible, and Marine riflemen were forced to flush out enemy troops with grenades and small arms. The brief fight in the trees yielded dozens of wounded Marines, but cleared a path for the rest of the regiment. By afternoon, elements of the 5th Marines had pressed inland and taken up strong defensive positions on the west and south sides of the airfield.

The Japanese, however, had no intention of surrendering the airfield without a fight. At 5:15 p.m., Marines watched in amazement as Japanese troops on the far side of the airfield emerged from cover and moved forward in a counterattack aimed at driving the Americans back to the beaches. The airfield constituted the only flat terrain on the island, a fact that the Japanese hoped to capitalize on by utilizing armor. Veterans would later disagree over precise numbers, but out in front of the enemy infantry were about 15 Type 95 Ha-Go light tanks.

As their lines surged forward, Japanese artillery shelled the Marine positions, but to little effect. The 5th Marines were, in fact, dug in and heavily armed. In anticipation of a potential armored attack at the airfield, Harris had ensured that his men were more than ready. The airfield was ringed with bazooka teams, 37mm guns, and multiple machine-gun pits.

The ensuing battle was furious but one-sided. The lightly-armored Japanese tanks sped across the runway, easy targets for American guns. Some of the tanks made it to the American lines, turning wildly in the Marine positions. Most were knocked out by hand grenades or bazookas, while those that escaped were attacked by Sherman tanks that pitched into the fight. The airfield was swept by machine guns, mortars, and naval gunfire that were called up in support. Surviving Japanese infantry, completely exposed without armored support, retreated in confusion.

To the north, Puller’s 1st Marines was experiencing far worse luck. Enemy fire from the Point continued to play havoc on the Marines, but rooting out the position’s Japanese defenders would be a bloody task. A maze of spider holes, bunkers, and pillboxes, the Point was defended by 500 Japanese. In addition to small arms, mortars, and machine guns, the 30-foot-high hill was defended by a 47mm anti-boat gun and four rapid-firing 20mm cannons.

The job of reducing the Point was assigned to K Company of the 1st Marine’s 3rd Battalion, commanded by Captain George P. Hunt. Hunt attacked with two platoons consisting of 102 men. Rather than attack the hill directly, Hunt swung east of the Point, endeavoring to assault the hill from the rear.

In spite of the maneuver, finding a weak spot in the Japanese defenses proved elusive. Hunt’s Marines fought their way up the Point under heavy fire, and paid a heavy price for the ground. Dedicated Japanese troops stubbornly defended every spider hole and pillbox, and blanketed the hillside with machine gun fire. His command steadily dwindling due to mounting casualties, Hunt nonetheless pushed his company uphill, slowly knocking out enemy fighting positions one by one.

The assault on the pillbox containing the 47mm gun was led by Lieutenant William Willis. While his riflemen kept up a steady covering fire, Willis dashed to the top of the pillbox and tossed a smoke grenade in front of the aperture to blind the Japanese defenders. Another Marine scored a direct hit with a rifle grenade which detonated inside the pillbox, starting a massive explosion and fire within the structure. Set afire by the blast, the last Japanese survivors darted from the pillbox but were cut down by the Marines. The Point had been neutralized, but at a terrible cost; two-thirds of Hunt’s company had been killed or wounded during the assault.

Far from resigning themselves to the American gains, the Japanese struck back. Aiming to isolate Hunt’s men, the Japanese counterattacked against a dangerous gap that had opened between the Point and the landing beaches. They succeeded in driving a wedge in the American line, occupying a strong position on Chavetal Ridge. Puller ordered a counterattack against the ridge, but it was repulsed amid well-directed machine gun fire. For the time being, Hunt’s men on the Point were on their own.

That night, the Japanese launched small-scale diversionary attacks in an attempt to infiltrate American lines and break up the tenuous toehold the Marines had established on Peleliu. In horrific scenes of night fighting up and down the beachhead, Marines fought off enemy attacks, often at close quarters when Japanese infiltrators leapt into foxholes. For young men on both sides, it was a nightmarish ordeal that would be repeated in the coming weeks.

The following morning, the Marines pushed hard for the airfield. The entire 5th Marines, bolstered by Puller’s 2nd Battalion, unleashed a massive attack at 8 a.m. All told, 4,500 men started forward at a walk, and were immediately taken under fire by Japanese mortars. Completely exposed on the flat expanse of the airfield, Marines broke into a run and plunged forward through a roaring tempest of artillery.

Despite the terrifying barrage, the advance of the 5th Marines couldn’t be stopped. Sprinting across the runways through smoke and shellfire, the Marines then poured into the tree line east of the airfield, clearing Japanese infantry out of rifle pits and machine gun nests. It had been a grand assault reminiscent of a 19th-century battle, and cost the Marines dearly. By the time they had captured the airfield, the regiment suffered an additional 300 casualties.

Skirting along the northern edge of the airfield, Puller’s 2nd Battalion ran into stiff enemy resistance amid the rubble of aircraft hangars and storage buildings. Making use of the ruins as improvised fighting positions, the Japanese fought stubbornly and slowed the Marine advance. The battalion fought into the afternoon before it cleared the ruins, then took up new positions on the island’s main thoroughfare, the East Road.

The 7th Marines continued its drive toward the island’s eastern shore. The attack progressed well until Hanneken’s Leathernecks ran into a 40-foot-diameter concrete blockhouse possessing four-foot-thick walls. The structure was bristling with machine guns and 20mm cannons, and it was the strongest defensive work on the entire island.

The immense structure was immune to both flamethrowers and 75mm tank guns, and Marine infantry suffered badly during repeated fruitless attacks. Engineers finally breached the blockhouse with a hefty charge of plastic explosives, and vengeful riflemen gunned down the stunned Japanese that stumbled out of the structure. After neutralizing the blockhouse, the 7th Marines succeeded in reaching Peleliu’s eastern coast, cutting off the remaining Japanese on the southern tip of the island.

Worse trials awaited Puller’s 1st Marines. On the morning of September 17, finally ready to push into the island’s central highlands, they began probing the forbidding and barren ridges northeast of the Point. The regiment’s battle for the Umurbrogol would be one of the bloodiest in the history of the Marine Corps.

The first troops to assail the tangled swath of limestone and coral were the 2nd Battalion, under the command of Lt. Col. Russell Honsowetz. Working their way to the East Road, the Marines then swung north but took fire from a craggy rise known simply as Hill 200. Honsowetz, under considerable pressure from Puller, directed an assault on the hill but found that he had committed his men to a meat grinder.

The entire hill was a maze of interconnected tunnels and caves, and as soon as it seemed that the Marines had gained ground, Japanese troops would emerge from subterranean positions and attack the Americans from the rear. It was a frustratingly slow fight, and casualties mounted.

Matters were only worsened by the tropical heat. The daytime temperature routinely soared to more than 110 degrees Fahrenheit, accompanied by unbearably high humidity. Heat exhaustion alone felled hundreds of Marines during the course of the campaign, and support units could rarely supply enough potable water to keep the Marines hydrated. Amid the blistering heat of the Umurbrogol, the Marines would experience the incomparable horrors of war.

After hours of brutal uphill fighting, Honsowetz’s Marines seized the narrow crest of Hill 200. They had suffered heavy casualties, particularly among officers. Although fired on from higher ground on the surrounding ridges, the Marines did their best to dig in for the night. Of the 400 men who had fought for the position, only half were still on their feet.

During the fight for Hill 200, Puller’s 1st Battalion had likewise been busy, first assaulting a Japanese blockhouse before turning into the Umurbrogol to attack Hill 160. Lt. Col. Ray Davis directed his men into some of the most difficult terrain in the area, and they were stopped cold by intense fire from a 6-inch naval gun and a 70mm mountain gun. An intrepid bazooka team knocked out the naval gun crew, but the 70mm gun proved a frustratingly difficult target.

Mounted on a rail track, the gun would emerge from a protected cave, fire, and then roll back into the cave for reloading. After the gun was fired on repeatedly, and unsuccessfully, a Sherman tank crew took up position just 100 yards from the gun, waited for it to reemerge, and then scored a direct hit that obliterated the target and its crew.

With the big gun out of commission, Davis’ Marines pushed into the Umurbrogol, clawing their way up the first set of ridges and seizing the summit of Hill 160. The sheer number of casualties was shocking even to veterans, and constituted an overwhelming task for burial details. Sergeant Jack Ainsworth, C Company, 1/1, recorded the tragic results of the first day’s fighting for the Umurbrogol. “There were many dead Marines, but we have no time to bury them,” wrote Ainsworth. “Mortar and artillery fire leaves its victims in horrible grotesque positions, partially decapitated, minus limbs.”

While the 1st Marines slugged it out in the Umurborgol, fighting continued elsewhere. During several days of fierce combat, the 7th Marines mopped up remaining Japanese resistance south of the landing beaches, and then captured two small islands situated off the coast. In the meantime, the Army’s 81st Division executed an amphibious landing on the island of Anguar on September 17. Making good progress after landing on the island’s eastern shore, the rookie troops of the 81st fought their way through heavy jungle and boxed in the Japanese on Romauldo Hill, the island’s best defensive terrain. Although the island was declared secure on September 20, it would take another month of tough fighting for the infantry to eliminate the last Japanese resistance.

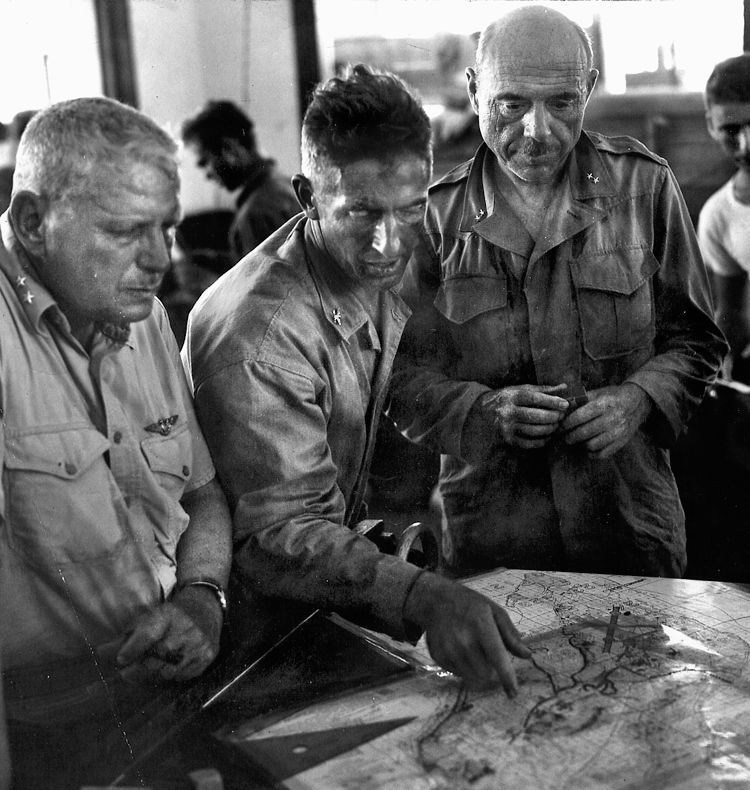

Harris, the 5th Marines commander, personally accompanied a reconnaissance flight over the Umurbrogol on September 18. He was appalled by what he witnessed. The landscape was clearly a nightmare for infantry, with “sheer coral walls, with caves everywhere, box canyons, crevices, rock-strewn cliffs, and all defended by well-hidden Japs,” he recalled.

Following the flight, Harris met with Rupertus and Puller, insisting that the Umurbrogol should be approached not from the south, where the Japanese expected it, but from the north. Both Rupertus and Puller, aggressive as ever, dismissed the idea and opted for a direct attack from the south. Disgusted by the prospect of seeing his men needlessly slaughtered, Harris decided to rely as much as possible on overwhelming firepower, or as he put it, “to be lavish with ordnance and stingy with men’s lives.”

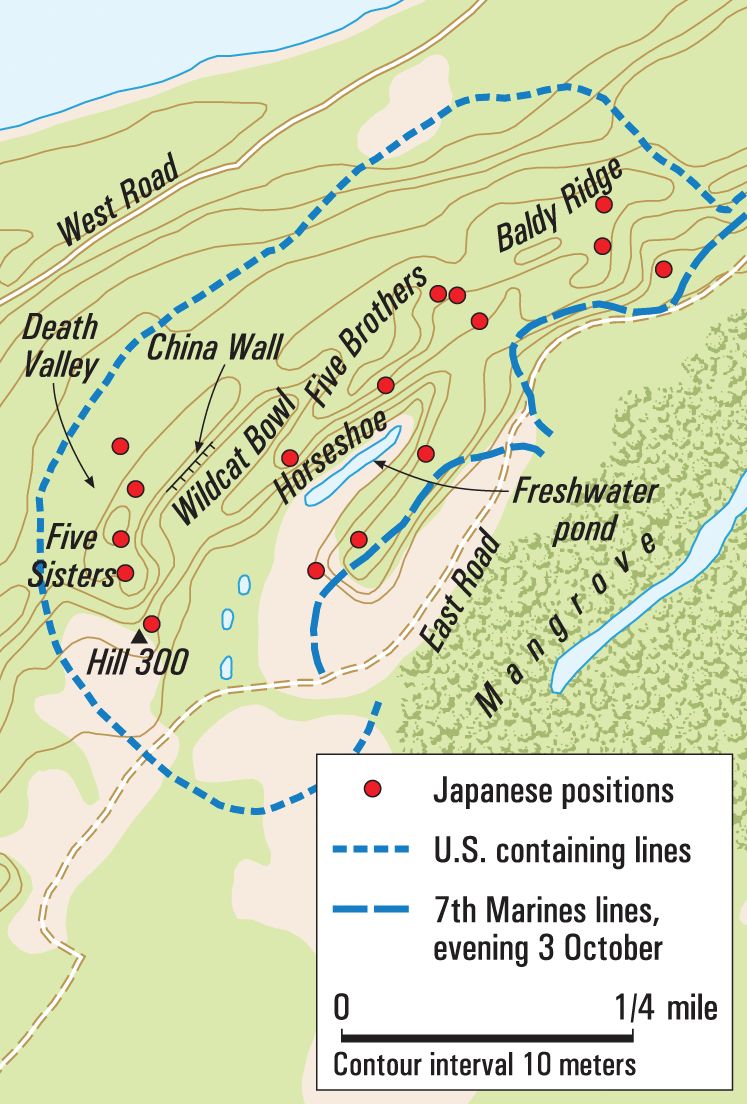

By September 19, Puller was grimly determined to throw his Marines into the heart of the Umurbrogol and break the back of Japanese defenses. The prime target would be an imposing hill mass identified as the Five Sisters, which commanded an enclosed valley nicknamed the Horseshoe. The key Japanese position had to be reduced, but it had a maze of tunnels. The Five Sisters could not be rightly called hills, but rather jagged pinnacles with sheer rock faces. Nearly impassable canyons lay between the Five Sisters.

Preparatory to an assault on the Five Sisters, Lt. Col. Spencer Berger’s 2nd Battalion of the 7th attacked Hill 300 early on the morning of September 19. Berger was shocked by the terrain, and horrified by the punishing casualties suffered by his battalion. Japanese fire poured down from the heights nearly uninterrupted, and after a day of bloody fighting, his men had gained just 300 yards of ground.

While Berger’s Marines slogged up the slopes of Hill 300, Honsowetz led the exhausted 2/1 into the heart of the Five Sisters. Working their way between the pinnacles, the Marines were subjected to intense Machine gun and mortar fire. Completely commanded by the heights, Honsowetz’s lead companies were hopelessly pinned down. Artillery fire was called in to break the Japanese stronghold, but proved useless against the sheer rock walls of the Five Sisters.

His blood clearly up, Puller thundered for more aggression from his subordinates. Erroneously convinced that the Japanese resistance was on the verge of breaking, he ordered more men forward. Weakened and understrength Marine companies were thrown piecemeal into the Umurbrogol hills, with predictable results. Aid stations were overwhelmed with casualties, and the regiment made negligible gains.

On September 21, Geiger, overall commander of the III Amphibious Corps, had had enough. Geiger had regularly visited the front lines to encourage his men, and grew increasingly frustrated with the costly bull-headed tactics employed by Rupertus and Puller. After privately conferring with Puller, Geiger announced his decision. The 1st Marine Division, which was little more than a broken shell after less than a week in combat, would be pulled from the line.

The fight in the Umurbrogol Pocket would be taken over by the 7th Marines and the Army’s 81st Division. The first army troops to arrive on the island, the 321st Infantry Regiment, came ashore on September 23. The next day, rather than be thrown directly into the mountains, the regiment, accompanied by the 3rd Battalion of the 7th Marines, began moving up the island’s West Road in order to skirt around the western edge of the Umurbrogol and completely encircle the Japanese position. Two days later, after tough fighting for a commanding enemy position known as Hill B, the bulk of Nakagawa’s troops were now completely isolated in the Umurbrogol Pocket.

Harris’ 5th Marines were ordered to the island’s northern sector, with the aim of eliminating remaining Japanese troops north of the Umurbrogol and capturing the smaller island of Ngesebus. After watching the 1st Division’s mauling during repeated frontal attacks, Harris was as determined as ever to implement a more measured combined-arms approach to the battle, bringing overwhelming firepower to bear with the aid of artillery, naval guns, and extensive air support.

With the Umurbrogol Pocket completely surrounded, the Americans continued the attacks against the enemy stronghold. A greater implementation of heavy firepower, including the use of tanks and flamethrowers, greatly helped to reduce the number of infantry casualties. The fight for the rugged terrain of the Umurborgol, however, would inevitably remain an infantryman’s fight. Remarkably, Peleliu was declared officially secure on September 27, but the horrors of combat would continue unabated as the Japanese were slowly forced into an ever-shrinking perimeter.

During the first week of October, the leathernecks of the 5th Marines were ordered into Umurbrogol Pocket. While Rupertus clamored for faster results, Harris stuck to a slower approach, trying to provide heavy firepower to his infantry. Bulldozers pushed open narrow tracks, allowing for tanks and flame-throwing Amtracs to reach deeper into the hill mass. Artillery pieces were transported to firing positions in the pocket in order to batter enemy positions from close range.

The Japanese, in fact, had likewise suffered horrendous casualties. On October 12, Nakagawa was down to just 1,150 men, armed with a shrinking stockpile of weapons and ammunition. They had been pushed into a shrinking perimeter centered on the Five Sisters and the two rugged valleys of the Horseshoe and Wildcat Bowl. Few were under any illusions that they would survive. Nakagawa and his men would fight to the death.

On October 14, the Marines tightened the noose on the remaining Japanese. While the 7th Marines attacked from the south, the 5th drove down from the north. As they advanced, the Marines enjoyed support from F4U Corsair fighters dropping napalm on Japanese positions. The napalm proved highly effective, forcing Japanese troops further into the tunnels in order to escape the inferno.

Two days later, much to the consternation of Rupertus, the Marines were pulled out of the line and replaced with the 81st Infantry Division, which would take over the final fight to eliminate the last Japanese. The remaining Marine regiments were little more than battered shells; the 5th Marines had suffered over 40 percent casualties during its one-month ordeal on Peleliu.

Implementing the combined-arms approach that Colonel Harris had long advocated, Army troops continued to gain ground, slowly eliminating Nakagawa’s troops and driving the last remaining Japanese diehards into a tunnel complex situated in the aptly-named Death Valley north of the Five Sisters. Nakagawa’s command post was deep in a jagged cliff face nicknamed China Wall.

Army engineers succeeded in building a ramp up the steep face of China Wall, allowing tanks and flame throwing Amtracs to close in on the last Japanese stronghold. A prisoner later revealed that on November 24, the Japanese 2nd Infantry Regiment’s flag was burned rather than fall into enemy hands. Nakagawa had committed suicide, denying the Americans a final triumph over the mastermind of the Japanese defense of Peleliu.

Far from culminating in a final, decisive action, the fight for Peleliu would painfully linger as little more than a grinding battle of attrition. Although major action ceased, isolated Japanese holdouts were hunted down for the succeeding months. In terms of lives lost and men injured, it was a costly experience to the bitter end. In that regard, Peleliu was a success for the Imperial Japanese Army. The first large-scale implementation of the new defense-in-depth tactics known as “fukkaku” had made the Marine Corps pay a painfully high cost for victory.

Ironically, the epic fight for Peleliu, one of the worst combat experiences in American military history, was barely covered by American newspapers. Overshadowed by more momentous events including the liberation of the Philippines and Operation Market Garden in The Netherlands, the seizure of an insignificant island in the Pacific was regarded as a minor affair.

With the benefit of hindsight, it became apparent that the entire campaign had been strategically unnecessary. As much as Halsey had feared prior to the invasion, the Japanese garrison on Peleliu posed no substantive threat to Macarthur’s landings in the Philippines. Including manpower losses on Anguar and the surrounding islands, the Japanese lost a staggering 14,000 men. Due to the Japanese penchant to scorn surrender in favor of death for the Emperor, the Americans captured just 400.

For the men who had struggled in the indescribable hell that was Peleliu, the battle left indelible memories. The vaunted 1st Marine Division had been wrecked as of spring 1945. For the seizure of Peleliu and Anguar, the Americans had suffered 2,336 killed and 8,450 wounded.

Perhaps the most fitting description of the Battle of Peleliu was later penned by Private First Class Eugene Sledge, whose K Company, 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines had endured horrific combat on the beaches, the airfield, and then the central highlands.

Umurbrogol was “a netherworld of horror from which escape seemed less and less likely as casualties mounted and the fighting dragged on and on,” recalled Sledge. “Time had no meaning; life had no meaning. The fierce struggle made savages of us all.”

A considerable body of opinion holds that even with the limited knowledge at that time about Japanese strength on the islands, there was no way they could affect MacArthur’s landing on Leyte. There was no naval capability and the air detachment had been destroyed. Any physical assets of the Japanese above ground could have been easily neutralized by American air and naval forces. It is rather surprising that Nimitz went along with the operation as usually he was much more calculating on the necessity of island invasions, wanting to avoid casualties where possible.