By Victor Kamenir

For Soviet Premier Josef Stalin and the people of the Soviet Union, the capture of Berlin was of great political and symbolic importance. Four years of total war had ravaged the western regions of the Soviet Union, leaving them a wasteland of destroyed cities, ruined industry, and decimated population. Stalin and his people deemed anything less than German unconditional surrender unacceptable. Every Red Army soldier who reached the Oder River knew it was his duty to the Mother Russia to rain down retribution on the Germans, and that there was no better place to avenge their people than Berlin.

The fall of Berlin was but a few months away when German Fuhrer Adolf Hitler addressed his people for the last time on January 30, 1945. The beleaguered German leader’s radio address came on the 12th anniversary of the founding of the Third Reich. That very night, just north of the German town of Kustrin, the lead elements of the Soviet 89th Guards Rifle Division crossed the Oder River under cover of darkness. Meanwhile, elements of the Soviet 44th Guards Tank Brigade succeeded in crossing just south of Kustrin.

Feeble German counterattacks against the two bridgeheads, which were 60 miles from the eastern outskirts of Berlin, over the course of the next two weeks failed to dislodge the Russian soldiers, who had entrenched as soon as they were across the last natural barrier between the Red Army and Berlin. In the weeks that followed, the Soviets pushed forward to secure the Reitwein Spur, a strategically important ridge that would play a key role in the preparation for the Red Army’s assault on Berlin. The Red Army forces on the west bank of the Oder succeeded in connecting the two bridgeheads on March 22.

By the end of March, though, the Western Allies were even closer to Berlin than the Red Army. By that time, the U.S. Ninth Army had crossed the Elbe River and stood poised to lunge at Berlin. Yet General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme commander of Allied Forces, believed that the German capital had no strategic value. Instead, he was concerned about strong German troop concentrations in southern Germany and Austria.

Eisenhower sent a telegram to Josef Stalin on March 28 advising him of the intention of the Western Allies to bypass Berlin and turn American forces south to prevent the Nazis from establishing an impregnable redoubt in the Alps. Allied intelligence had learned that Hitler wanted to construct a fortified redoubt in the Austrian Alps that might support thousands of troops.

Although Stalin agreed with Eisenhower, the Soviet premier nevertheless harbored deep mistrust toward the Allies and questioned their motives. What is more, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery disagreed with Eisenhower and believed that the Allies, who were just 50 miles from Berlin, should capture the Nazi capital before Soviet forces. Stalin was apprehensive that the Germans might surrender Berlin to the Allies and conclude a separate peace that would allow Germany to seek favorable terms at the conclusion of the war.

Stalin called 48-year-old Marshal Georgy Zhukov, the commander of the 1st Belorussian Front, and Marshal Ivan Konev, the commander of the 1st Ukrainian Front, to Moscow for a conference on April 1. He intended to discuss the need for an immediate push to capture Berlin. Indeed, the staffs of both generals had already drawn up plans for just such an attack. At the meeting, the two generals presented their plans to Stalin.

Stalin bestowed the honor of taking the German capital to Zhukov. The 1st Ukrainian Front to its south and the 2nd Belorussian Front under Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky to the north would provide direct support. Forces of the three fronts totaled 800,000 men, 3,100 tanks and self-propelled howitzers, and 20,000 artillery, mortars, and rocket launchers.

By March, both the 1st Belorussian and 1st Ukrainian fronts had reached the Oder and Neisse rivers, the last significant geographical barriers east of Berlin. The 1st Belorussian Front had established the bridgehead at Kustrin.

Strong German defensive positions atop Seelow Heights on the west bank of the Oder blocked the Red Army’s most direct route to Berlin from the Kustrin bridgehead. Situated 10 miles west of the point where the Highway 1 crossed the Oder River at Kustrin, Seelow Heights rose 157 feet above the Oder. Although relatively low, the heights provided a commanding position overlooking the wide river.

Hitler had approved the appointment on March 21 of General-Colonel Gotthardt Heinrici to command Army Group Vistula, which was composed of General of the Armored Forces Hasso von Manteuffel’s Third Panzer Army, which defended the lower Oder, and General of the Infantry Theodor Busse’s Ninth Army, which had the difficult assignment of defending the middle Oder, which guarded the most direct approach to Berlin for the Soviet forces.

The 58-year-old recipient of the Knight’s Cross excelled at defensive warfare and had proven himself repeatedly commanding forces in the Army Group Center on the Eastern Front. At times, while commanding the German Fourth Army in 1942, he had been outnumbered 12 to one. He knew how to hold a defensive line with as few men as possible with as little loss of life as possible. Nevertheless, he faced a daunting task defending the Oder line. He not only faced a shortage of experienced troops, but also severe shortages of tanks, artillery, ammunition, and fuel.

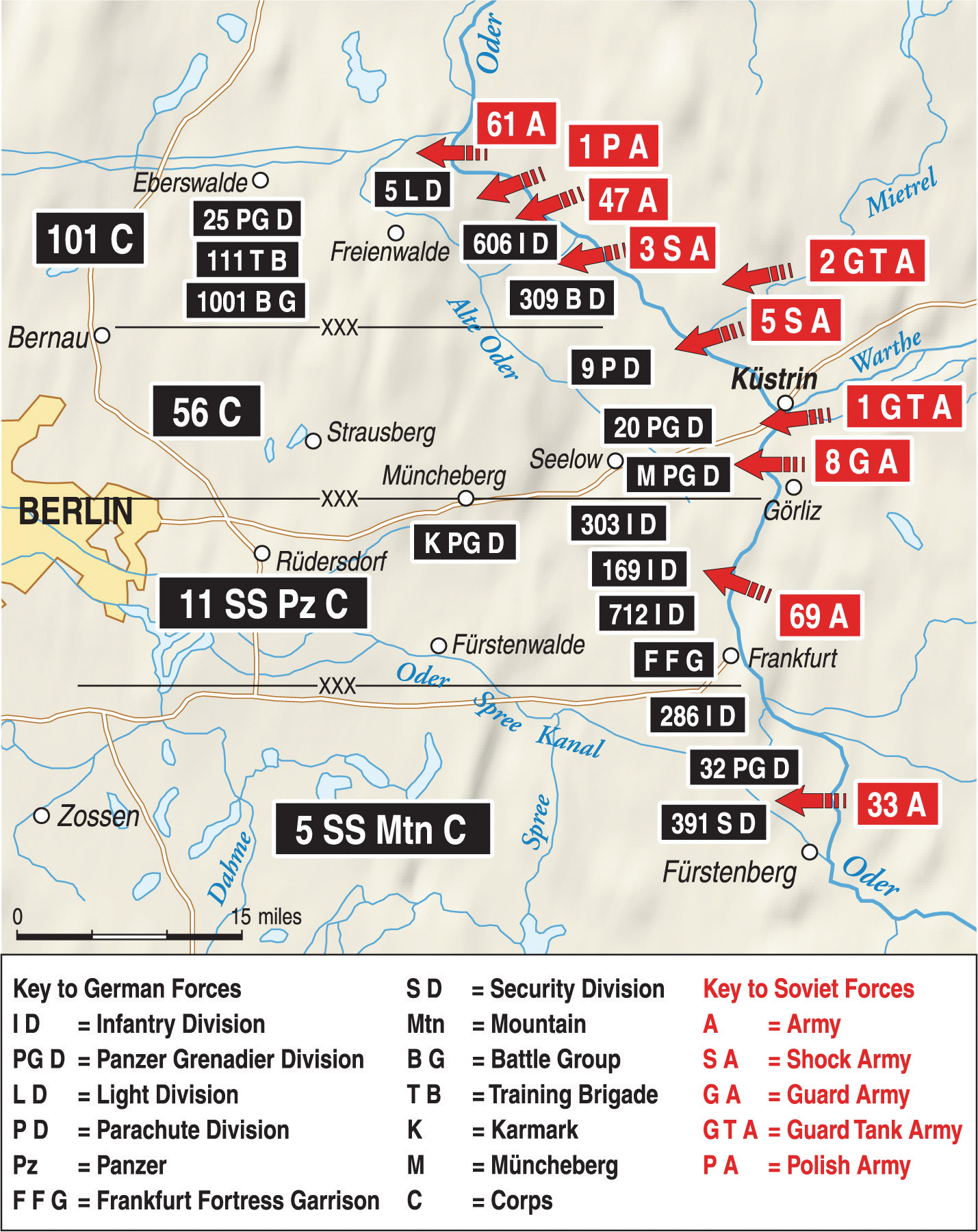

Busse’s Ninth Army defended the sector that stretched from the Finow Canal in the north to Guben in the south. The newly formed army consisted of 112,000 men in 15 divisions, 512 tanks, and 2,625 artillery, mortars and antiaircraft guns. General of the Artillery Wilhelm Berlin’s CI Army Corps held the northern flank between Oderberg and Letschin, General of the Artillery Helmuth Weidling LVI Panzer Corps held the center section anchored on Seelow Heights, and SS-Obergruppenfuhrer Matthias Kleinheisterkamp’s XI SS Army Corps held the southern sector.

In addition, Colonel Ernst Beihler’s garrison occupied Frankfurt-an-der-Oder on the east side of the river. Hitler had declared it a fortress, meaning that it had to be defended to the last man. SS-Obergruppenfuhrer Friedrich Jeckeln’s V SS Mountain Corps held the extreme southern flank of the Ninth Army. To the south of the Ninth Army was General der Panzertruppe Fritz-Hubert Graser’s Fourth Panzer Army. Graser’s army comprised the V Armee Corps, Panzer Corps Grossdeutschland, and LVII Panzer Corps.

The Germans had worked tirelessly for the past 15 months to construct three lines of defenses on Seelow Heights. The three fortified lines, which had a depth of between 10 to 15 miles, were from east to west the Hauptkampflinie, Hardenberg-Stellung, and Wotan-Stellung.

These defensive lines were a network of trenches, bunkers, minefields, and anti-tank defenses. In front of the heights was an antitank ditch that was 15-feet deep and 15-feet wide, and was protected by minefields. German artillery and machine-gun nests were positioned to sweep the ground in front of the ditch.

The steep eastern slopes of the heights, as much as 30 degrees in places, made them virtually impassible to armor. Having faced massed Soviet armor attacks, the Germans developed a concept that called for placing antitank artillery behind forward defensive positions to engage Soviet armor breakthroughs at short range. Every defile even marginally accessible by tanks bristled with German antitank guns and self-propelled howitzers in hull-down positions.

The Germans established other defensive positions on the reverse slopes, out of direct fire of Soviet artillery. The whole area was studded with small towns and hamlets turned into strongpoints. The German infantrymen manning each defensive position were furnished with ample supplies of the panzerfausts. The panzerfaust was a disposable, single-shot, recoilless weapon that mounted a high-explosive antitank warhead.

German combat engineers had flooded the plain between Seelow Heights and the Oder River, known as the Oderbruch, in spring 1945 by releasing water from an upstream reservoir. The flooding was exacerbated by spring thaws. A web of canals, which in dry weather could be crossed by tanks, had become small rivers over which bridges would have to be built.

The Soviet 1st Belorussian Front, which faced Seelow Heights, comprised nine all-arms armies and two tank armies. Positioned on the east bank of the Oder in the north were the 61st Army and the 1st Polish Army. In the Kustrin bridgehead on the west side of the Oder were the 47th Army, 3rd Shock Army, 5th Shock Army, and the 8th Guards Army. The 5th Shock and 8th Guards armies faced the strongest German opposition, where the State Highway 1 crossed Seelow Heights. On the south flank on the east bank were the Soviet 69th Army and the 33rd Army. In reserve on the east bank were the 1st Guards Tank, 2nd Guards Tank Army, and 3rd Army.

Zhukov planned to use the 8th Guards and the 5th Shock armies to pierce the German defenses. Once they opened a gap, the marshal planned to commit the 1st Tank and 2nd Tank armies to exploit the opening. Zhukov ordered Colonel-General Ivan Katukov to ensure that his 1st Tank Army reach the eastern suburbs of Berlin on the second day of the offensive. Since it was important to advance as quickly as possible into Berlin, the marshal instructed Katukov to capture Berlin with just his tank army, rather than waiting for the slower- moving infantry formations behind him to catch up.

At dawn on April 15, the Russians conducted a reconnaissance-in-force to determine the strength and location of enemy artillery and strong points. Each division of the 8th Guards Army and the 5th Shock Army deployed an infantry battalion reinforced with tank and artillery to participate in the intelligence-gathering effort.

Intermittent fighting continued throughout the day, with the Soviets largely unsuccessful in their efforts to locate German artillery positions. This was partly because the Germans had anticipated the reconnaissance-in-force and had concealed their artillery.

On the night of April 15, Zhukov moved the 1st Guards Tank and 2nd Guards Tank Armies into the Kustrin bridgehead. Each tank army consisted of two tanks corps, a mechanized corps, a heavy tank brigade, and at least one self-propelled artillery brigade. Each army had approximately 800 tanks and self-propelled howitzers and 750 artillery pieces, mortars, and rocket launchers.

At 3:00 a.m. on April 16, Soviet artillery began pounding the German Ninth Army’s forward positions. The purpose of the bombardment, which lasted for 30 minutes, was to overwhelm the Germans with the sheer volume of fire. Participating in the bombardment were Soviet 203mm heavy howitzers, which fired a 220 lbs. shell. The Russians had packed as many as 270 pieces of artillery on each mile of their front. The Soviets fired during their artillery barrage 1.2 million shells for a total of 98,000 tons, according to Zhukov.

“A deafening noise fills the air,” wrote Friedrich Schoeneck, a soldier in the German 309th Infantry Division “Compared to everything that has gone before, this is no longer a barrage, it is a hurricane that tears everything up above us, in front of and behind us. The sky is glowing red, as if it was about to burst. The ground wobbles, shakes and rocks like a ship in a force 10 wind.”

Next, thousands of flares shot into the sky. This was the signal for the female Soviet soldiers operating the 143 searchlights stationed every 200 yards to illuminate the battlefield and blind the German defenders. As they did so, General Vasilii Chuikov’s 8th Guards Army and General Nikolai Berzarin’s 5th Shock Army began their advance. The searchlight plan backfired, though, by enabling the Germans to see the exact location of the advancing Soviet troops.

“The troops did not receive real help from the use of searchlights after the artillery preparation; the battlefield was covered in a wall of smoke, and it was impossible to understand whether the searchlights were functioning or not,” wrote Chuikov. “In fact, such illumination did not help; on the contrary, it complicated the offensive. The light of the searchlights, reflecting from the night fog and smoke, blinded the advancing soldiers; moreover, against the background of such lighting, the silhouettes of the advancing troops became more visible to the enemy.”

Weathering the artillery barrage, German troops reoccupied the first line of defenses in time to meet Chuikov’s attack. The 8th Guards Army attacked with all three of its corps deployed in line of two echelons, with each division advancing on a front of 1,400 yards. The 8th Guards Tank Army operated in direct support of the infantry. Advancing among the attacking infantry were 82 IS-2 heavy tanks, 27 T-34 medium tanks, 14 ISU-152 heavy self-propelled howitzers, and 34 SU-76 self-propelled howitzers. Leading the attack were the tanks of the 166th Tank Regiment, equipped with mine rollers designed to detonate antitank mines and clear a passage in the minefields. The mine-roller tanks were closely followed by engineers and infantry, with heavy tanks and self-propelled guns in close support.

The Soviet tanks and infantry moved the first two miles over the waterlogged ground without resistance. The attackers soon ran into canals and streams crisscrossing the valley floor, and tanks and self-propelled guns began to fall behind the infantry. “The surviving enemy guns and mortars came to life at dawn and began shelling the roads along which our troops moved in dense formations,” recalled Chuikov. “Command and control were disrupted in some regiments and battalions. All of this affected the pace of the offensive.”

Especially heavy resistance was met along the Haupt Canal running at the base of the heights. The water in the canal was sufficiently deep to prevent tanks and self-propelled guns from fording it. The advance halted while Soviet combat engineers built bridges under fire. The narrow roads leading to the heights became packed with halted Soviet troops, unable to maneuver off-road due to swampy ground and minefields.

The reprieve came from Soviet ground-attack and fighter aircraft striking German positions in depth. After the canal was crossed, the direct attack on the heights began.

Hemmed in by swampy ground and minefields, Soviet armor could advance only along the narrow roads under direct German artillery fire. Heinrici’s two armies had just 1,344 artillery pieces and flak guns used as artillery. These included 88mm Flak guns, 50mm Pak-38s, 75mm Pak-40s, 88mm Pak-43, and 37mm Flak guns. When a German gun knocked out the leading tank, the next tank in line would push the disabled tank off the road and continue the advance. This was repeated countless times as the Soviet forces advanced.

Soviet tanks could not navigate the steep slopes of the Seelow Heights. As they maneuvered to seek out narrow defiles, they presented vulnerable sides to antitank fire, and more and more burning Soviet tanks littered the slopes. Soviet infantry was hesitant to advance into the storm of lead. Everyone knew the war was practically over, and no one wanted to die this close to victory.

Despite heavy casualties and ever-increasing German resistance, by noon on April 16, the 8th Guards Army had fought its way through the first line of German defenses and reached the second, but could not break through. On the night before the Red Army’s main attack, the majority of the German troops had withdrawn to the second defensive line in accordance with orders Heinrici had previously issued in order to minimize their losses during the bombardment that preceded the Soviet advance.

After nine hours of unsuccessful attacks, Chuikov ordered his command to stand down and bring up artillery for the next attack, set to go off at 2:00 p.m. Zhukov, who was in overall control and maintained close contact with Chuikov, also remained in constant communications with the Soviet Supreme Command in Moscow.

The Soviet armies to the north of Chuikov, while failing to achieve a breakthrough, made some inroads into German positions. The 5th Shock Army reached Platkow-Gusow, and the 3rd Shock Army came within miles of Letschin. The Polish 1st Army forced the Oder River north of Neulewins, while the Soviet 47th Army was heavily engaged near Wriezen. Although hard-pressed and suffering serious casualties from concentrated Soviet artillery fire and air attacks, the German Ninth Army’s positions remained mostly intact.

The hastily prepared follow-on attack in the early afternoon was also unsuccessful in the face of withering enemy fire. As a result, Soviet casualties were higher than anticipated. Zhukov had deployed the 1st Tank Army in the same sector as the 8th Army to lend more weight to the Soviet attack. Moscow supported him in that decision.

Four narrow roads led from the Oder to the Seelow Heights in the sector of the 8th Guards Army. When the tank units of the 1st Guards Tank Army began moving forward, the situation along the roads became even more chaotic. The tanks of 1st Guards Tank Army came up behind the artillery of the 8th Guards Army, which could not get off the road to let the tanks through. The elements of the two armies became intermixed and entangled. German artillery falling among tightly packed Soviet columns created significant confusion and casualties.

Unable to untangle from the massive road jam, only parts of Katukov’s 1st Tank Army attempted to close with the enemy. “The steepness of the eastern slopes reached 30 to 40 degrees,” wrote Colonel Amzasp Babadzhanyan, the commander of the 11th Guards Tank Corps. “In this regard, when climbing, the tanks were forced to bypass steep slopes, cliffs, and fell into a fiery dead end, unable to turn around and leave the sector already clogged with other tanks, and thereby expose the sides to the fire of enemy antitank weapons.”

Heinrici’s artillery in the second defensive position atop the heights pummeled the Soviet forces attempting to scale the escarpment. “Everyone who rushed forward instantly burned, because a whole enemy artillery corps stood at the heights and the defense on the Seelow Heights was not broken,” wrote Katukov. The Soviets lost 200 tanks and suffered heavy casualties that included 29 brigade, regimental, and battalion commanders.

The 5th Shock Army to its right, which was commanded by General Nikolai Berzarin, had reached the Alte-Oder River midway to Seelow Heights, while 69th Army on the left, which was led by General Vladimir Kolpakchi, did not have any success at all. Zhukov was forced to report to Moscow that the offensive was not developing as planned; however Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front to the south had made good progress against the German Fourth Panzer Army, forcing the Neisse River in the sector between Forst and Muskau and penetrating German defenses up to twenty miles in depth.

Stalin always fostered a spirit of competition among his senior commanders. Stalin knew that Zhukov and Konev were bitter rivals, and so he pitted them against each other in a contest to see who could reach the German capital first. To spur Zhukov to intensify his effort, Stalin ordered Konev to wheel north his 3rd and 4th guards tank armies and have them advance on Berlin. In so doing, Stalin hoped the competition between the front commanders would produce beneficial results.

At dawn on April 17, the 1st Belorussian Front renewed its attack, which was preceded by another massive artillery barrage that lasted 30 minutes. When the guns stopped, Soviet ground-attack aircraft swept in to pound the German positions. Heavy fighting erupted overhead as Luftwaffe aircraft battled Soviet aircraft drawn from the Soviet 16th and 18th air armies. Given that the Luftwaffe barely had enough fuel to put its fighter planes aloft, it was not long before the Soviets achieved air superiority.

In heavy fighting, the 11th Guards Tank Corps was able to achieve complete penetration of the second defensive line on a narrow front up to six miles. The 5th Shock Army made similar progress. Next, Katukov committed the 8th Guards Mechanized Corps to exploit the success.

The Germans committed two reserve divisions to defend the heights, the 28th Motorized and the 168th Infantry. Constant German counterattacks pinned down the left flank of the 8th Guards and 1st Tank Armies.

Meanwhile, Graser’s Fourth Panzer Army to the south pulled back the forces on its left flank under pressure from the 1st Ukrainian Front. Rather than committing his two reserve panzer divisions to shore up his northern flank, Graser kept them in the center. By nightfall, though, the positions of the German units defending Seelow Heights had become untenable. Unless the Ninth Army pulled back in line with the Fourth Panzer Army, it faced encirclement.

The Fourth Panzer Army “was torn into three isolated parts,” wrote Konev afterwards. “One of its groups was cut off on our right flank, in the Cottbus area; the second, in the center, continued to fight against us in the woodlands of the Muskau region; and the third was also cut off on the left flank in the Gurlitz area.”

At the end of the second day, the 11th Guards Tank Corps had reached the northern outskirts of the town of Seelow. Soviet armor and infantry advanced along narrow roads against intense opposition from German troops. Panzerfaust teams exacted a heavy toll in Soviet armor.

German infantry equipped with panzerfausts sought to knock out the lead tank, as well as the last tank, in order to bring the column to a halt. Once that was done, they would systematically knock out the rest of the tanks in the column. The shaped charge at the front of the Panzerfaust warhead made a hole more than two inches wide and sent a stream of molten metal into the tank’s cabin, which killed or maimed the crew and destroyed the equipment inside.

The effective range of a panzerfaust was 200 feet, and casualties among the German panzer grenadiers ran high. Soviet infantry in close cooperation with the tanks had to dig out pockets of German resistance. Muzzle flashes from the launchers immediately drew Soviet return fire. In turn, Russian tanks blasted the German positions at point-blank range. The tank crews then assisted the infantry of the 8th Guards Army in clearing the Germans from the town.

“All the streets and crossroads in Seelow were cluttered with vehicles, tanks, self-propelled guns,” recalled Katukov. “Enemy artillery was still shelling the town, and air battles still flared up in the sky, but Seelow was ours.”

Once past Seelow Heights, the Russian troops advanced west towards Berlin, driving the Germans before them. The fighting was particularly ferocious at Muncheberg, which was situated halfway between Seelow and Berlin. Soviet forces fought their way into the town. Determined to hold the town, SS forces counterattacked. The town changed hands three times before the Russians secured it. By the end of the day on April 17, the 8th Guards Army had captured the second defensive lines in its sector of the Seelow Heights and exited the Oder River valley.

The 1st Belorussian Front continued the advance on April 18 in the face of heavy resistance, bypassing the Seelow Heights from the north. The Soviet 47th Army and the 3rd Shock Army launched heavy attacks against the CI Army Corps at Bad Freienwalde on the left flank of the German Ninth Army, forcing its collapse.

As for Generalleutnant Arnold Burmeister’s 25th Panzergrenadier Division, it tried to reestablish contact with the left flank of Generalmajor Josef Rauch’s 18th Panzergrenadier Division from the LVI Panzer Corps near Protzel just west of Wriezen.

The 9th Parachute Division and the Panzer Division Muncheberg, which had been recently formed in the nearby town of the same name, became heavily engaged directly north of the Reichstrasse in the Gusow sector against the Soviet 5th Shock and the 2nd Guards Tank armies.

Muncheberg essentially was a powerful kampfgruppe. It included 11 Tigers, 11 Panthers, and eight Panzer IV tanks, as well as four Stug assault guns. Its troops put up spirited resistance to the Soviet armor before eventually withdrawing in the face of superior forces.

On the south flank of the heights, the Germans counterattacked with 11th SS Panzergrenadier Division Nordland, 23rd SS Panzergrenadier Division Nederland, and the 503rd SS Heavy Tank Battalion. The 503rd battalion was equipped with 10 69-ton Tiger II tanks. The Tiger II heavy tank combined the Tiger I’s thick armor with the armor sloping of the Panther tank, which improved its survivability in battle.

The delays on the third day infuriated Zhukov. He repeatedly harangued his army commanders, exhorting them to take up positions with their lead corps to direct their forces. He also instructed them to bring forward all available artillery, even their heavy-caliber guns, to within two miles of the front line.

“[As you near Berlin] the enemy will resist and cling to every house and bush,” he told his generals. “Therefore, tankers, self-propelled gunners, and infantry should not to wait until the artillery will kill all the Nazis and provide the pleasure of moving through cleared space.”

The Red Army had succeeded by April 19, the fourth day of the battle, in opening a 15-mile gap in the German front between Wriezen and Behlendorf, thereby splitting the German Ninth Army wide open. The 25th Panzer Grenadier Division was thrown back to Eberswalde. To make matters worse, Red Army forces threatened to encircle its right flank. The Polish 1st Army had succeeded in crossing the Alte Oder River near Am Ranfter, thereby threatening German forces at Bad Freienwalde. In addition, the Soviet 47th Army, reinforced with the 9th Tank Corps, captured Wriezen.

The 3rd Shock army under Colonel-General Vasilii Kuznetsov cleared the last positions of German CI Army Corps, opening the way for General Semyon Bogdanov’s 2nd Guards Tank Army to enter the breakthrough. The 5th Shock Army forced the survivors of the German 9th Parachute Division to retreat northwest to Neu-Hardenberg.

At that point, Chuikov’s 8th Guards Army and Katukov’s 1st Guards Tank Army overcame the last resistance of German LVI Panzer Corps on Seelow Heights. Soviet 82nd Guards Rifle Division resumed their advance at midday on April 18 and captured Muncheberg after desperate fighting in the streets of the town. Following the fall of Muncheberg, German resistance noticeably weakened. By the end of the day, the German front had disintegrated. All that remained was the need for the victorious Soviet forces to mop up pockets of resistance in order to open a path to Berlin. On the German right flank between Carzig and Lebus, the XI SS Corps had to pull back to maintain contact with the LVI Panzer Corps.

The offensive of the 1st Ukrainian Front reached the area of Luckenwaldes south of Berlin on April 19. This forced the Germans to abandon Frankfurt-an-der-Oder. The retreating Germans attempted to withdraw west to Berlin, but the 1st Belorussian and 1st Ukrainian fronts succeeded in encircling the south flank of the German Ninth Army and the V Army Corps from the Fourth Panzer Army southwest of the Seelow Heights in the area of Zossen-Bad Saarow. Nearly 200,000 German soldiers became trapped in the pocket. Afterwards, there were no more organized German units between the Seelow Heights and Berlin.

In the evening, Katukov received a dispatch from Zhukov.

“The 1st Guards Tank Army is entrusted with the historical mission of being the first to break into Berlin and hoist the Victory Banner,” stated the dispatch. “You are personally charged with its execution. Send the best brigade from each corps to Berlin and assign them the task of breaking through to the outskirts of Berlin no later than 4:00 a.m. on April 21 at any cost.” Racing to Berlin, Katukov’s tankers reached Berlin’s suburbs that day.

But it would be several more days before Berlin was completely encircled. At midday on April 24, the lead elements of the 4th Guards Tank Army from the 1st Ukrainian Front forced the Havel River and linked up with the 47th Army of the 1st Belorussian Front, closing the ring around Berlin. On the same day, reconnaissance units from the 1st Ukrainian Front linked up at Torgau on the Elbe River with the advancing U.S. 1st Army.

Six armies from the 1st Belorussian Front, including Chuikov’s 8th Guards Army and the two tank armies, and three armies from the 1st Ukrainian Front, including two tank armies, participated in the battle for Berlin. Defended by close to 200,000 men, 3,000 guns, and 250 tanks, the city was a virtual fortress.

The German defenders converted massive concrete and steel buildings into veritable bunkers bristling with machineguns and cannons. The streets were blocked with barricades up to four yards deep. The defenders had an ample supply of panzerfausts, which proved deadly against Soviet tanks in the narrow confines of the city.

The veterans of Chuikov’s 8th Guards Army, who had fought at Stalingrad, used their street-fighting experience in storming Berlin. Each infantry platoon or company was reinforced by several tanks, a self-propelled howitzer, several artillery pieces, and detachments of combat engineers and radiomen.

Clearing the city block by block, and paying a heavy price in men and machines, the Soviet troops worked their way closer and closer to the center of the city. Hitler committed suicide on April 30, ushering in the opportunity for unconditional surrender, which occurred on May 7.

After the war, Zhukov was criticized for a frontal attack against the Seelow Heights rather than bypassing them from the north and south. He was decried for putting his desire to be the first in Berlin over the lives of his men. Although initially battering against strong and determined resistance, the forces of Zhukov’s leading armies eventually found a week spot in German defenses and pierced them on a narrow front, allowing his tank formations to exploit the breakthrough. Soviet casualties during the fighting for the Seelow Heights were 30,000 killed and wounded. As for the Germans, they suffered 12,000 casualties.

Zhukov’s frontal attack pinned down the forces of the German Ninth Army and prevented them from retreating to defend Berlin. The majority were pushed southwest of the heights, where they were subsequently encircled and taken prisoner, thus denying many of Hitler’s veteran troops the opportunity to defend the German capital.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments