By Robert L. Durham

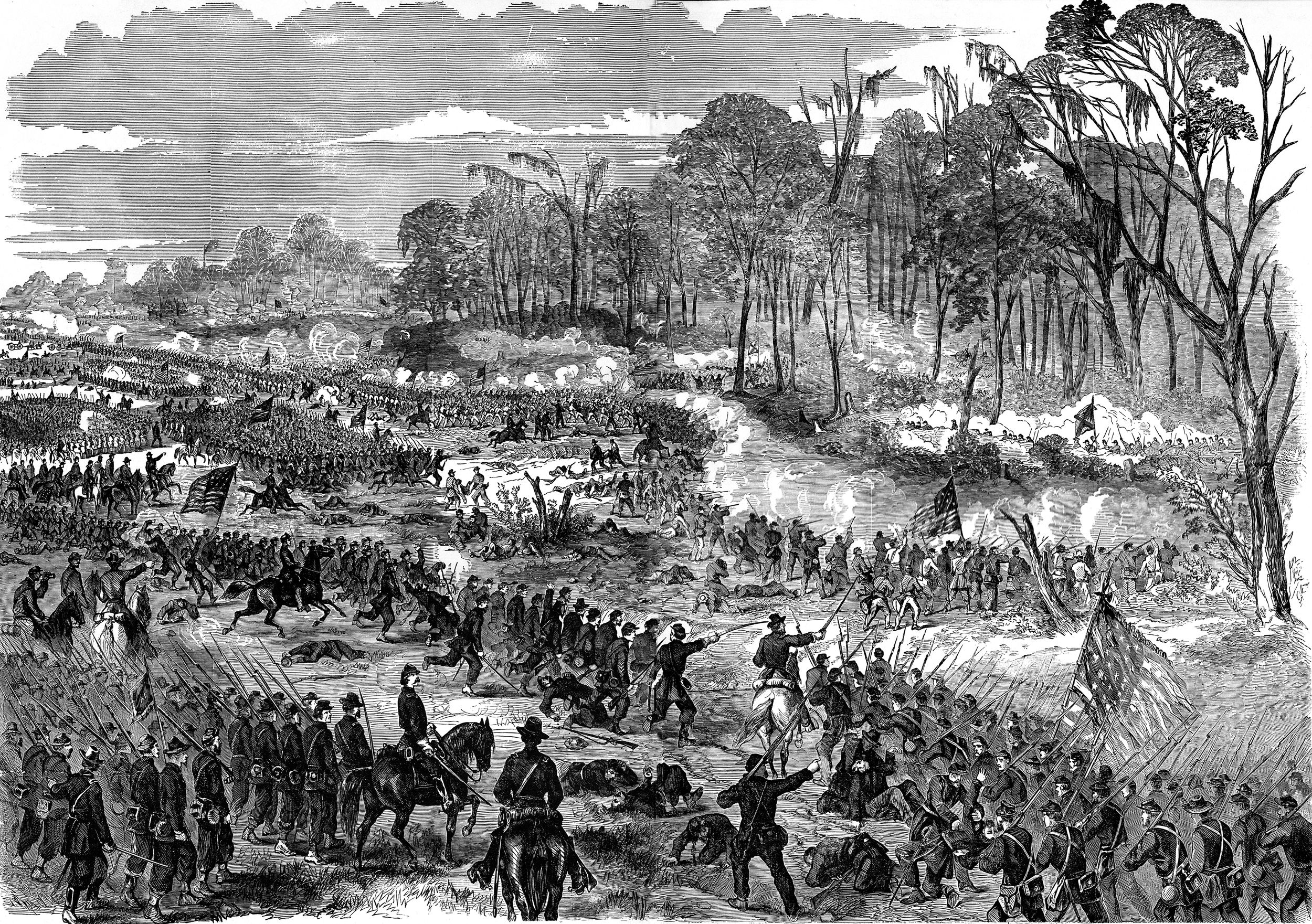

The barren summit of Champion’s Hill presented an ideal site for Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton’s Confederate army to deploy artillery batteries on the morning of May 16, 1863. If the Union soldiers of Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s Army of the Tennesee wanted to take out the artillery, they would have to push through deep ravines choked with tangled underbrush in order to reach the summit.

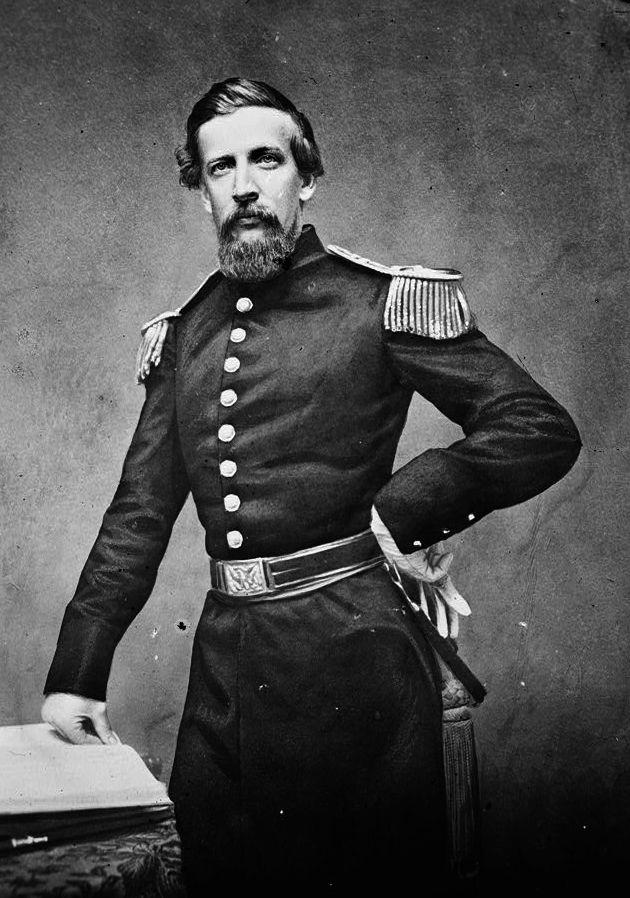

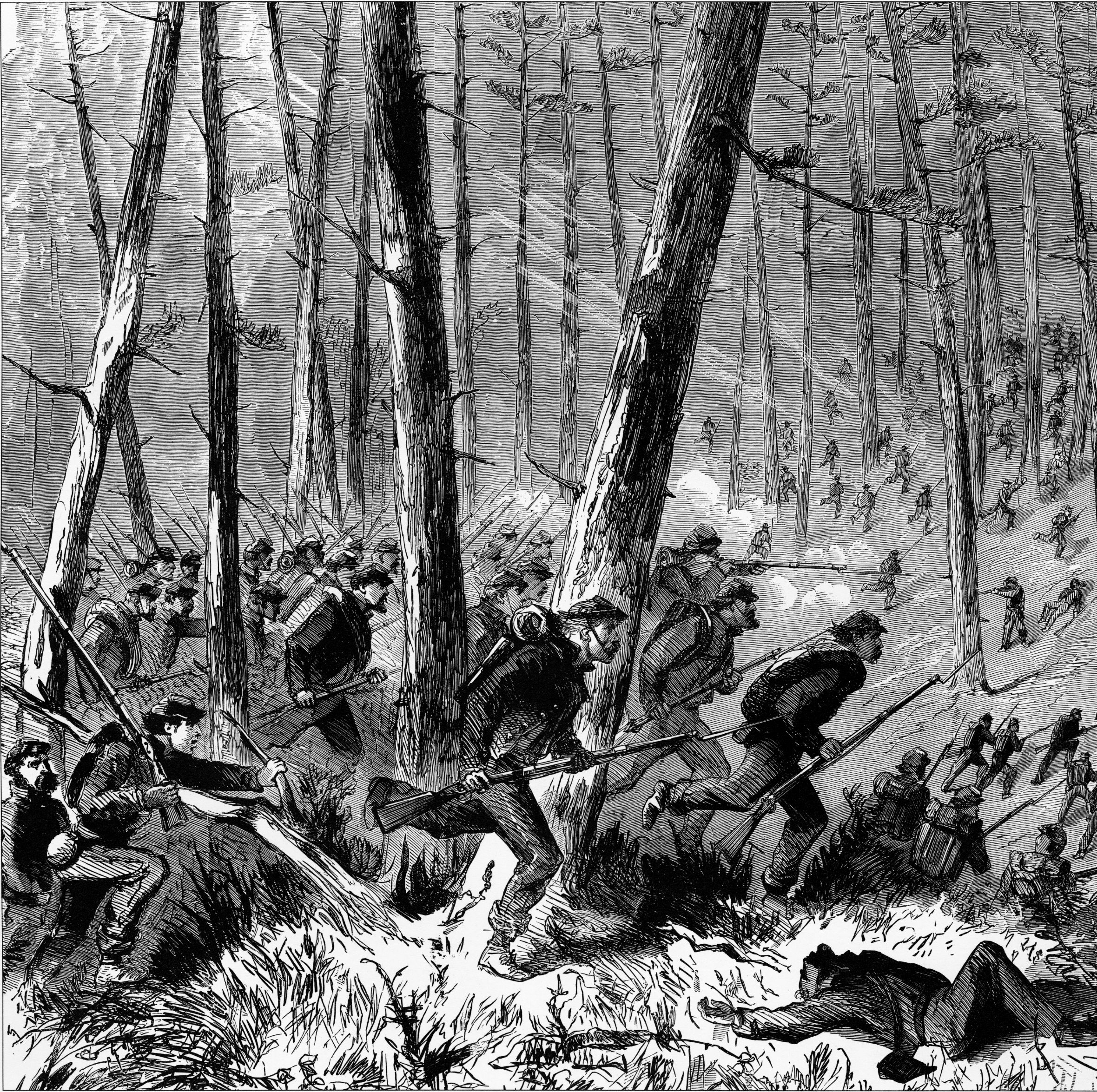

But that was exactly what they did at the start of the battle. As the Yankees of Brig. Gen. George F. McGinnis’ brigade neared the crest of the hill, Captain James F. Waddell’s Alabama Battery loaded its guns with canister rounds designed to repulse infantry at close quarters.

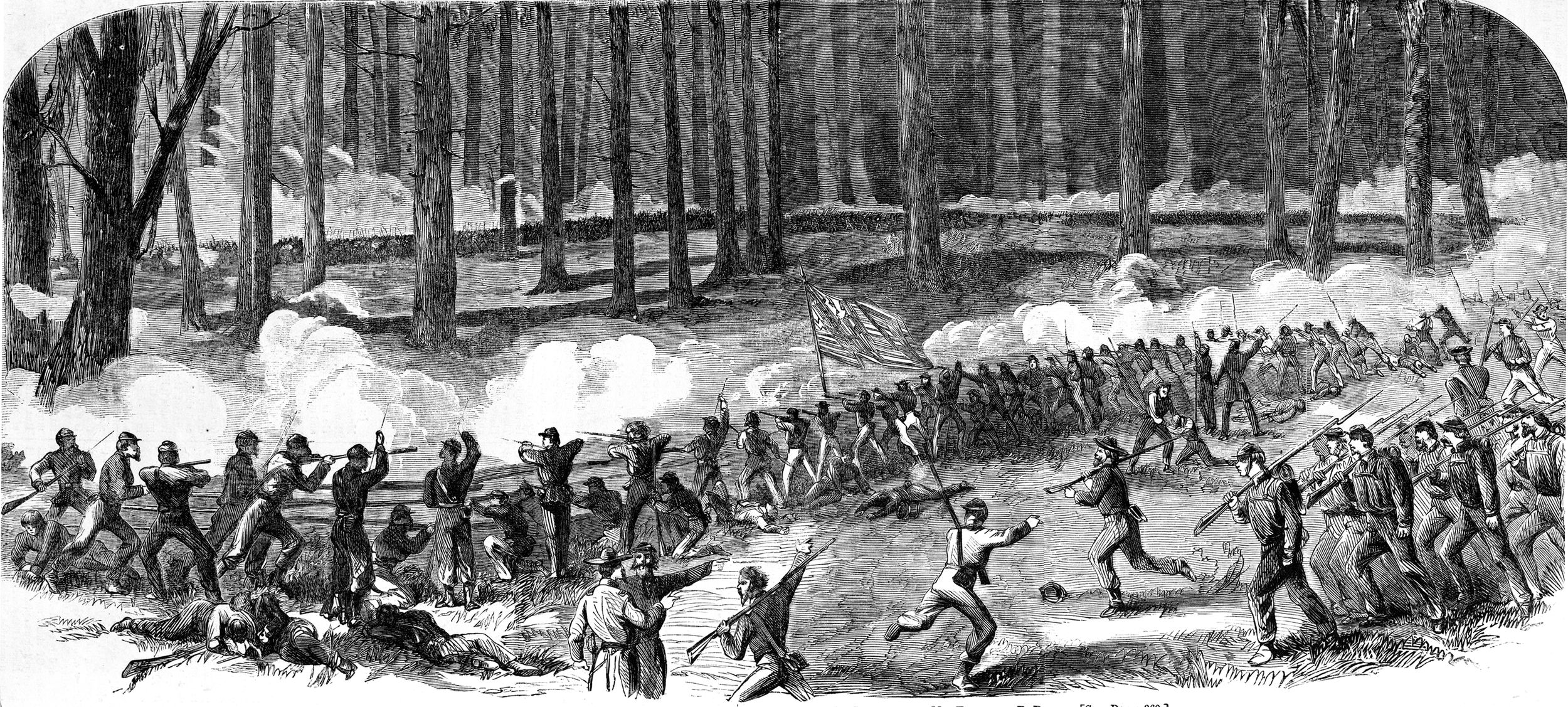

McGinnis’ Yankees fixed bayonets as they made their way towards the summit and the menacing Confederate artillery. When they were 75 yards from the battery, McGinnis issued orders for his troops to lie down to avoid the Confederate artillery fire. When the Confederate gunners fired their guns, the tin cans containing the iron balls tore open as soon as they left the barrel, but their contents whisked over the heads of the prone Federals.

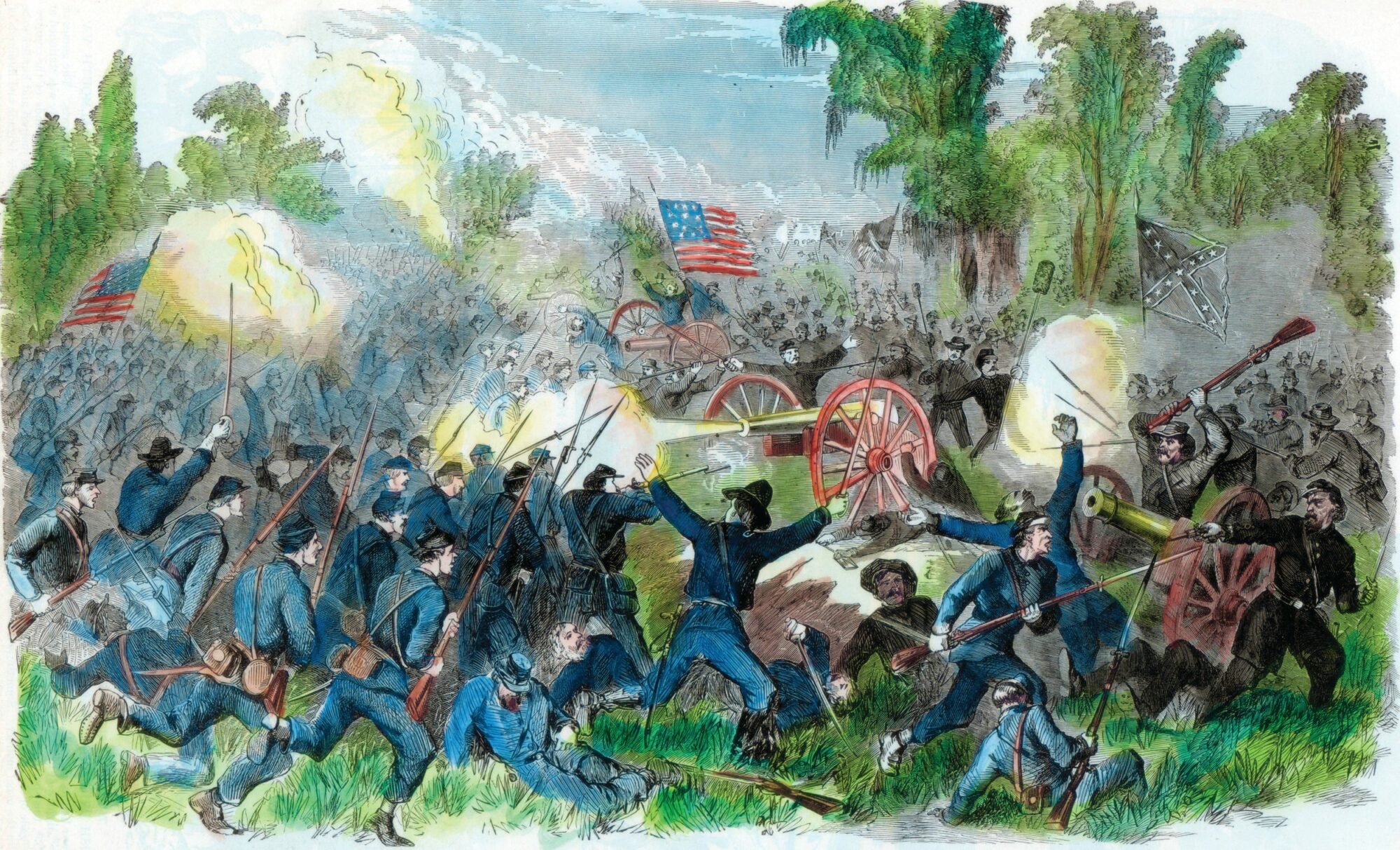

The 11th Indiana was the first unit to gain the crest of Champion’s Hill, but McGinnis brought up Colonel Thomas H. Bringhurst’s 46th Indiana to reinforce the other Hoosiers already on the summit. The 46th Indiana came on at the double-quick and captured the guns. Confederate infantry, however, rallied and counterattacked in a bid to retake the guns.

“At this point occurred one of the most obstinate and murderous conflicts of the war,” wrote McGinnis. The two sides fired on each other at point-blank range and fought each other with clubbed muskets and bayonets. Some fell to the ground dead, while others screamed in agony from terrible wounds. Charge followed countercharge as each side sought to vanquish the other atop Champion’s Hill. The struggle for the Confederate guns on the crest of the hill would prove to be one of the most savage contests of the battle.

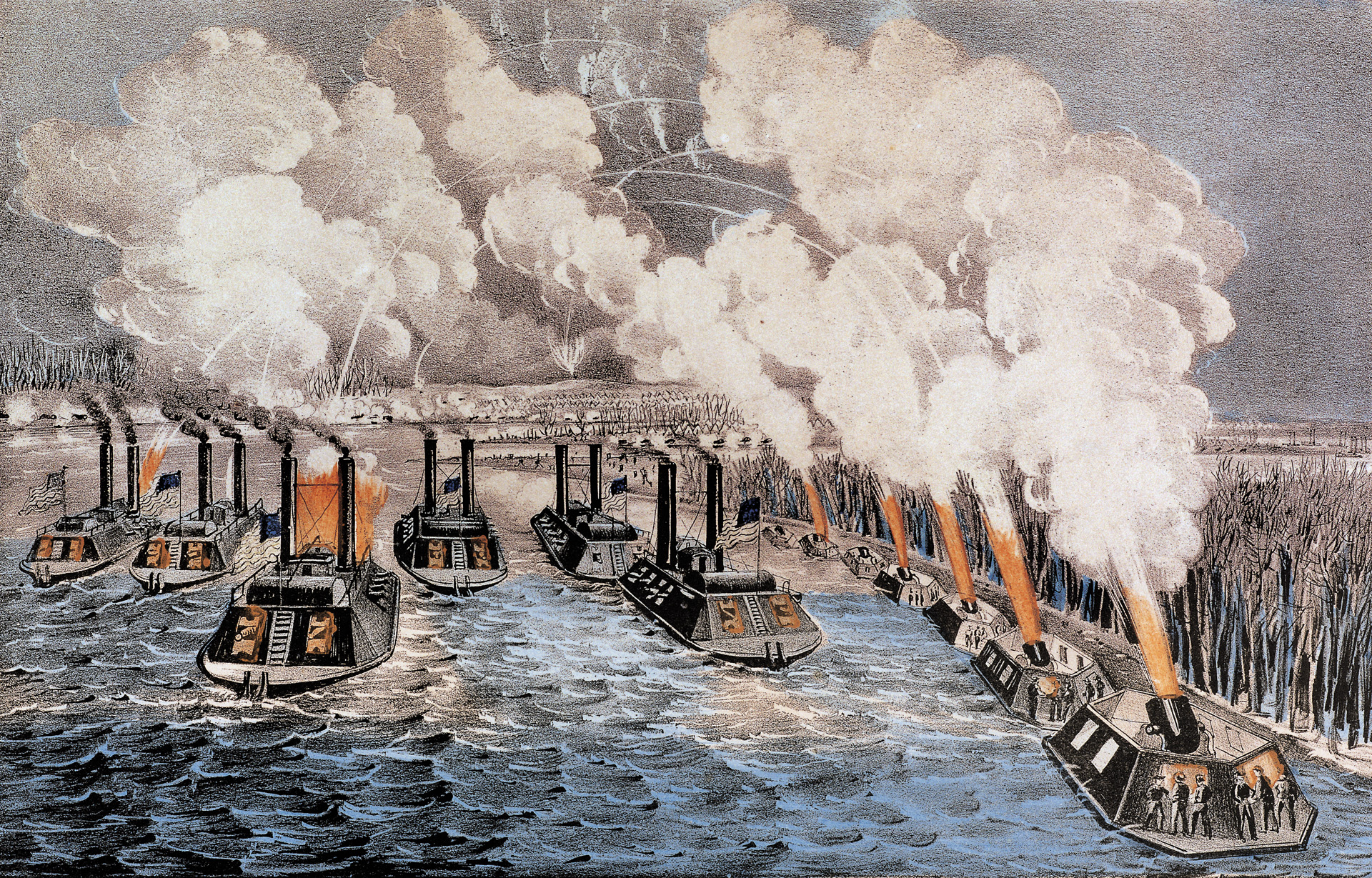

The culmination of Grant’s four-month campaign to secure the most formidable Confederate stronghold remaining on the Mississippi River at Vicksburg began on April 30, 1863. Vicksburg held an almost impregnable position on the east bank of the Mississippi River. The Confederates possessed Vicksburg, Mississippi, and Port Hudson, Lousiana, which prevented the U.S. Navy’s brown-water naval squadron from accessing a 130-mile stretch of the Lower Mississippi River.

Holding this crucial section of the river also enabled Richmond to keep a line of communications open with Confederate forces in the Confederacy’s Trans-Mississippi Department.

Grant dispatched Colonel Benjamin Grierson on April 17, 1863, on a cavalry raid through the heart of Mississippi in order to draw off Confederate troops from the Vicksburg defenses. At the same time, Colonel Abel Streight set off two days later on a raid to destroy parts of the Western and Atlantic Railroad in north Georgia in order to pry the Confederates from Chattanooga, Tenneseee.

The Union high command reasoned that if the Confederates could conduct successful mounted raids into enemy-held territory, so could the Union army. Grant and Rear Admiral David D. Porter maintained steady pressure on Confederate forces holding the last section of the Mississippi River.

Porter steamed past the Vicksburg batteries on two occasions in mid-April with his gunboats and transports. These successful naval expeditions made it possible for Grant to transport 17,000 troops across the Mississippi River below Vicksburg.

Grant marched his troops down the west bank of the river in April to Bruinsburg, Mississippi. From that location, Porter’s transports ferried them to the east side of the river on April 30. Grant’s troops began marching inland the following day.

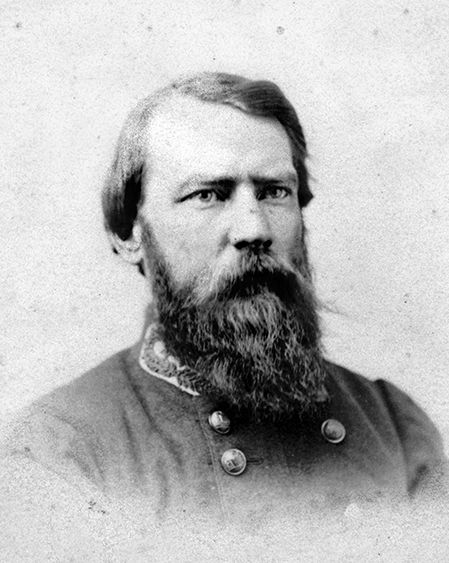

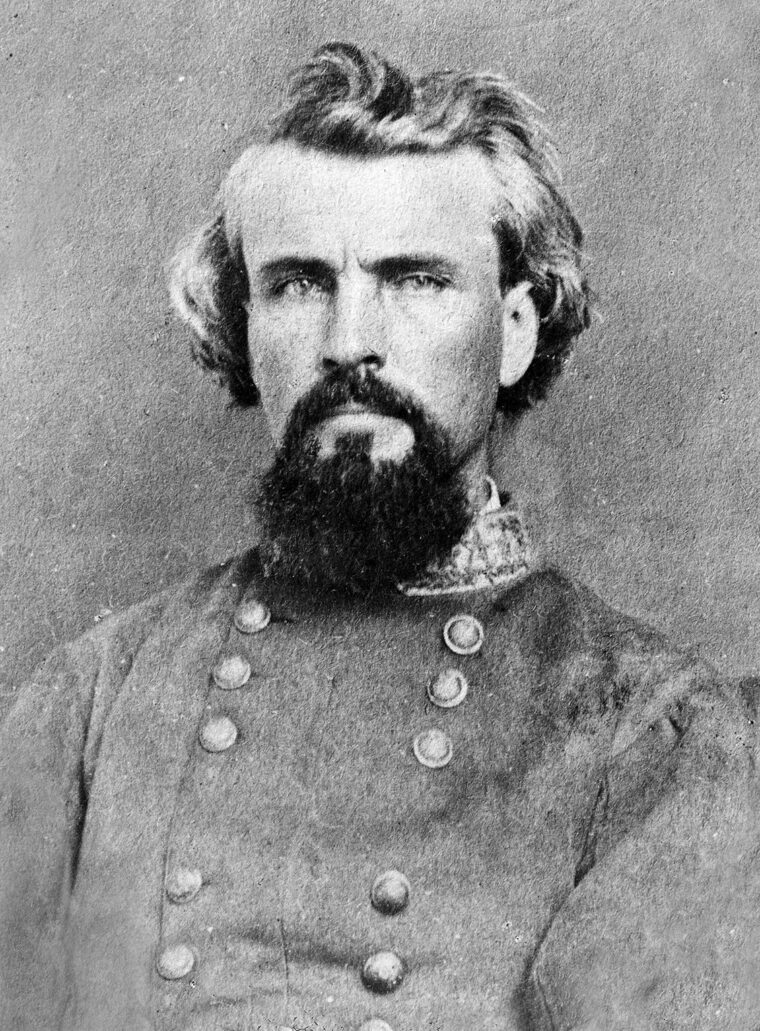

Pemberton commanded the Confederate Department of Mississippi and East Louisiana. The Confederate government entrusted him with holding Vicksburg for the Confederacy. The Pennsylvania-born Confederate commander expressed surprise that Grant succeeded in getting his troops across the Mississippi. But he knew that Grant was up to something since he had been receiving regular reports that the Union commander was moving troops south along the west bank of the river.

Instead of sending troops to block possible landing points on the east bank, Pemberton dispatched a portion of his infantry to counter the advance of Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s XV Corps into northern Mississippi. Lacking sufficient cavalry to screen Sherman’s advance, Pemberton had no other option but to send a large force of infantry to check Sherman’s movements.

Grant ordered Sherman to conduct a feint against Confederate forces at Snyder’s Bluff, north of Vicksburg, while the other two union corps crossed the Mississippi River below the city. Sherman subsequently marched south and crossed the Mississippi in a similar fashion to Grant’s other two corps.

As soon as Grant had established his bridgehead at Bruinsburg, he sent Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand’s XIII Corps to lead the march into the Mississippi interior followed closely by James B. McPherson’s XVII Corps.

McClernand ran headlong into Brigadier General John S. Bowen’s infantry division, which Pemberton had dispatched to slow Grant’s advance. In the sharp clash that followed, McClernand prevailed. After brushing aside Bowen, McClernand set off for Raymond, Mississippi, which was situated just 20 miles from the Mississippi state capital at Jackson.

Grant had orders from Washington to march south and link up with Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks, the commander of the Army of the Gulf, in order to capture Port Hudson. Once he had united with Banks, the combined force was to countermarch north to capture Vicksburg. Grant did not like the idea, however, given that Banks had seniority over him. Fortunately for Grant, Banks, who was campaigning west of the Mississippi River, decided to march against Confederate forces under Maj. Gen. Richard Taylor in Alexandria, Louisiana. With Banks deliberately avoiding an attack on Port Hudson, Grant was free to continue his offensive against Vicksburg without interference from Banks.

Pemberton committed his troops in a piecemeal fashion against Grant. He sent Brig. Gen. John Gregg’s brigade to take up a blocking position behind Fourteen Mile Creek. McPherson, who outnumbered Gregg by more than three to one, smashed his meager force in the Battle of Raymond on May 12.

To strengthen the defense of Vicksburg, Confederate President Jefferson Davis had ordered Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston to Mississippi on May 9 to take personal command of the effort to defend Vicksburg. Johnston arrived by train in the Mississippi capital on May 14 after a circuitous train ride from Tennesee that took him through Atlanta, Montgomery, Mobile, and Meridian. “I arrived this evening finding the enemy’s forces between this place and General Pemberton, cutting off communication,” he wired despondently to the Confederate government in Richmond, Virginia. “I am too late.”

Grant initially had planned to move directly on Vicksburg from Raymond, but when he learned that Johnston had scraped together Confederate reinforcements at Jackson, Grant decided to knock Johnston out of the fight before turning west to Vickburg. Grant sent the two corps of McPherson and Sherman to capture Johnston’s position at Jackson.

As two-thirds of Grant’s army advanced on Jackson, Johnston ordered an evacuation of the city. Johnston had just two brigades, those of Gregg and Brig. Gen. W.H.T. Walker, totaling 6,000 men at Jackson. Gregg had marched to Jackson from Port Hudson, while Walker had arrived from the east as reinforcements from General P.G. T. Beauregard’s Department of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida.

Johnston faced 25,000 Union troops at Jackson. Knowing he was heavily outnumbered, Johnston instructed Gregg to fight a delaying action to cover the evacuation of the city. Once the evacuation was over, Johnston intended to abandon the city.

After hard marching on muddy roads in torrential rains, Sherman’s troops approached the town from the southwest on May 14 while McPherson bore down on it from the northwest astride the Vicksburg and Jackson Railroad.

McPherson attacked the main Confesions of the two Union corps drove Gregg’s troops into the city’s fortifications. When the last Confederate supply train exited the town at mid-afternoon, Gregg withdrew his men north to join the rest of Jackson’s troops.

The Confederates sacrificed 17 guns in the process as they withdrew seven miles north of the city to Tugaloo where Johnston planned to wait the arrival of reinforcements from the East. Union troops took possession of the city in the late afternoon and unfurled the Stars and Stripes atop the state capitol building.

Grant wanted to wreck the railroads in Jackson so that it could no longer serve as a transportation hub for the Confederacy. He ordered Sherman “to remain in Jackson until he destroyed that place as a railroad center and manufacturing city of military supplies.” Sherman’s troops set fire to foundries, machine shops, warehouses, factories, arsenals, and other public property.

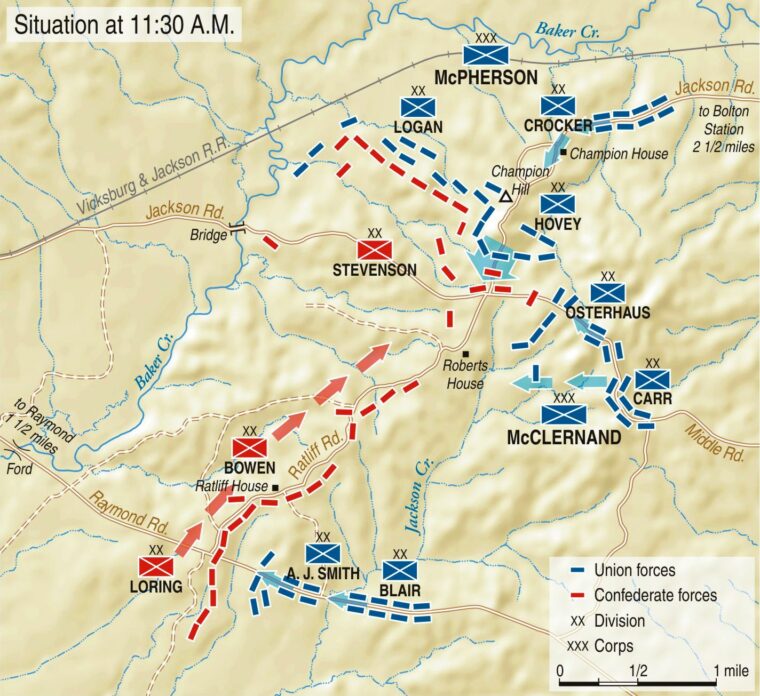

Having driven Johnston out of Jackson, Grant abandoned the city and turned back towards Vicksburg. Grant’s Army of the Tennessee, which was traveling on three parallel roads, passed through Clinton on the morning of May 16 and continued west toward Edward’s Station on the east bank of the Big Black River. As the Union army advanced westward, it ran into Pemberton’s defenses along Ratliff Ridge overlooking Jackson Creek that covered the Middle Road and the Raymond Road.

Ratliff Ridge extended south Champion Hill, a commanding height that rose 100 feet above the surrounding terrain. The area in which Grant and Pemberton would do battle that day consisted of ridges, ravines, sunken farm lanes, and stands of timber. Champion Hill itself “was bald, giving the enemy a commanding point for his artillery, and was really the key of the position,” wrote McPherson.

Baker’s Creek skirted the battlefield to the west and three roads crossed it. Raymond Road crossed Baker’s Creek on the Lower Bridge. At the time of the battle, the torrential rains of the previous day had carried away the bridge. Pemberton instructed Major Samuel H. Lockett, his chief engineer, to oversee the immediate repair of the bridge.

A second road, known as Middle Road, paralleled Raymond Road to the north. A third road, known as Jackson Road, ran in a north-south direction across Champion Hill. It met the Middle Road on the other side of the hill, at a crossroad. From there, the Middle Road became part of Jackson Road. The latter turned west and crossed Baker’s Creek by way of the Upper Bridge. The north-south road, at that point became the Ratliff Road, and it continued to join the Raymond Road at the Coker farmhouse.

The first contact came at midmorning on the Raymond Road when the skirmishers of Brig. Gen. Andrew J. Smith’s Tenth Division of McClernand’s corps made contact with the skirmishers of Maj. Gen. William W. Loring’s division. Grant had given McClernand explicit orders not to bring on an engagement, and the corps commander had passed those along to Smith.

Smith in turn told Brig. Gen. Stephen G. Burbridge, who commanded the first brigade of the division, to scout the enemy position but not to bring on a general engagement until the rest of the division had come up.

As the two sides skirmished, Loring fell back to Coker House Ridge. Smith mistakenly believed he had succeeded in driving back Loring’s troops, but Pemberton had ordered Loring to pull back his troops to the ridge. The skirmishing continued with other units on both sides deploying skirmishers as well. With the Union guns already in action, the Confederates began firing their artillery as well.

Brigadier General Peter J. Osterhaus’ Ninth Division of McClernand’s corps came up against Brig. Gen. Stephen D. Lee’s Second Brigade of Maj. Gen. Carter L. Stevenson’s Division on the Middle Road in front of the crossroads. The crossroads was a strategic intersection of the Jackson Road, the plantation road, and the Middle Road, which led southeastward to Raymond.

Osterhaus, operating under the same orders as Smith, did not press the Confederates. He established a skirmish line, unlimbered his artillery, and awaited further orders.

Although neither side moved aggressively against the other, casualties occurred in the fighting along the Middle and Raymond roads. A wellaimed shot by Confederate artillerists struck one of Osterhaus’ caissons causing a large explosion. Union artillery also caused considerable carnage.

As Pemberton listened to the sounds of skirmishers on the southern half of the battlefield, a messenger arrived with an urgent dispatch from Johnston. The dispatch contained a message from Johnston informing Pemberton that he had evacuated Jackson. It also contained orders instructing Pemberton to join forces with Johnston in the vicinity of Clinton, which was situated 14 miles west of Jackson.

Although Pemberton desired to link up with Johnston, his 22,000 troops were spread out over a wide area and engaged against the vanguard of Grant’s army. Pemberton did, however, send a reply to Johnston informing him that he would attempt to pull back to Edwards Station and march his troops from that location to Clinton.

As a preliminary step, Stevenson sent a detachment to escort Pemberton’s train of 400 wagons toward Baker’s Creek, and stand guard at the crossroads. While the opposing forces continued skirmishing, the Confederate wagons began withdrawing.

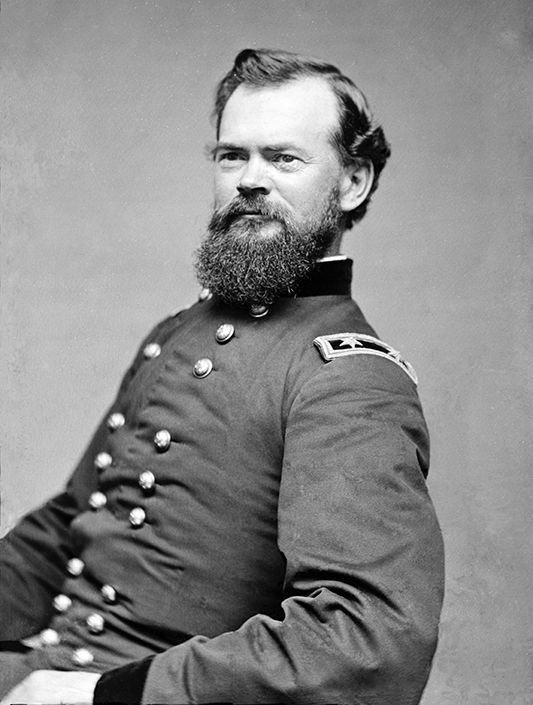

The northern half of the battlefield where Champion’s Hill was situated experienced a different type of fighting than that which had unfolded on the southern half of the battlefield along the Raymond and Middle roads. Brig. Gen. Alvin P. Hovey’s Twelfth Division of McClernand’s corps and Gen. John A. Logan’s division of McPherson’s XVII Corps proceeded west along the Jackson Road toward Champion’s Hill. Grant accompanied McPherson. He was eager to trap Pemberton before he had a chance to join forces with Johnston.

Spying the Union infantry advancing along Jackson Road, Confederate skirmishers deployed on the hill notified Lee. The intrepid Confederate brigadier led the five regiments of his Alabama brigade from their position on Middle Road to the crest of Champion’s Hill. To maintain the integrity of the Confederate line of battle, Brig. Gen. Alfred Cumming’s Third Brigade of Stevenson’s division deployed his troops in Lee’s former position on the Middle Road.

Grant, who had 32,000 troops on hand with which to engage Pemberton, established his headquarters at the Champion house. McGinnis, of Hovey’s division, sent skirmishers forward to drive off a Confederate patrol. McGinnis first rode to within 300 yards of Champion’s Hill to reconnoiter the Confederate position. He then rode to Grant’s headquarters where he informed the Union commander of the nature of the terrain on which they would be fighting.

McGinnis informed Grant that the ground consisted of cultivated fields, as well as hills and ravines covered with timber and choked with undergrowth. Despite the rugged terrain, Hovey urged Grant to attack the Confederates; however, Grant told him he would not make a general attack until all of McPherson’s troops were at hand.

Hovey, whose Twelfth Division was composed of just two brigades, returned to his command and completed the deployment of his command by moving Colonel James R. Slack’s Second Brigade into position to the left of McGinnis’ First Brigade. Logan arrived at 10 a.m. and deployed his troops in a way that extended the Union line to the west.

Logan positioned Brig. Gen. John E. Smith’s First Brigade and Brig. Gen. Mortimer D. Leggett’s Second Brigade to the right of McGinnis while holding Brig. Gen. John D. Stevenson’s Third Brigade in reserve. A half hour later, the Union troops began their advance on the northern half of the battlefield. Hovey’s troops moved up the north slope of Champion’s Hill and Logan’s two brigades advanced on his right.

Three Union batteries went into action to support the attack. Lee’s Confederates had just reached the crest of Champion’s Hill when the Union vanguard attacked. Lee’s Alabamans fired crashing volleys that checked the advance of Hovey’s blue ranks.

“Our artillery was hastened forward from point to point, over the numberless hills of this most rugged country, and poured its deadly fire into the Confederates,” wrote Reverend Thomas M. Stevenson, the chaplain of the 78th Ohio.

John Stevenson brought his Third Brigade around to the far right of Brig. Gen John E. Smith’s brigade and swept around Lee’s flank. The soldiers of one of Stevenson’s regiments, the 32nd Ohio, were eager to restore their reputation, which had been tarnished the previous year when they surrendered at Harper’s Ferry. Colonel Benjamin F. Potts led the Buckeyes in a furious charge against the Confederates.

Meanwhile, McGinnis’ First Brigade of Hovey’s division moved forward to engage Lee’s Alabamians until he discovered another body of Confederates closing in on his right flank. He halted his troops and redirected them to fire on the advancing Confederates. McGinnis’ infantrymen fired heavy volleys into the enemy, while Union artillery pounded the Confederates. The combination of musket and artillery fire stopped the Confederates cold. “From the edge of the timber we drove the enemy, step by step, for nearly 800 yards, over deep ravines and abrupt hills,” wrote McGinnis.

Cumming’s Georgians came up at this time minus two regiments left behind to contain Osterhaus’ troops. They went into position to the right of Lee’s Alabamians. Cumming formed his brigade on rough ground that was heavily timbered. A gap soon appeared between Lee and Cumming. To address the problem, Cumming detached his left regiment to fill the gap, but the two right regiments had to stay where they were to protect an Alabama battery stationed at the crossroads. Equally troubling for the Confederates, a 300-yard gap also existed between Cumming’s forward position and the regiments at the crossroads. Cumming was in the process of straightening his battle line when the Federals struck. Their musketry staggered the Georgians.

Carter Stevenson observed the fighting on Champion’s Hill and requested reinforcements from Pemberton. Pemberton responded by ordering Brig. Gen. Seth Barton’s Georgia Brigade to his assistance. Barton, whose troops were deployed in support of Cumming’s two regiments at the crossroads, detached one regiment and a section of artillery to secure the Lower Bridge at Baker’s Creek. Barton then ordered the rest of his Georgians into position to the left of Lee’s Alabamians. With hardly time to deploy, they drove John Stevenson’s skirmishers back into the brigade’s main line.

McGinnis’ Hoosiers had prevailed in the bloody struggle for Waddell’s guns atop the crest of Champion’s Hill. After hand-to-hand fighting that lasted about five minutes, two of the three regiments of Cumming’s Georgia Brigade were routed. Slack’s Midwesterners then struck Cumming’s right flank hard, which made the rout complete. In the process, they captured four more Confederate guns.

As the contest for Champion’s Hill heated up, McPherson ordered both Logan and Hovey to assault the Confederates holding the crest of the hill. Captain Max Corput’s Cherokee Georgia Artillery, which was attached to Barton’s brigade, opened a brisk fire on Logan’s men.

Logan’s troops, who had been marching at the double-quick, arrived on the battlefield eager to join the fight. McPherson and Logan rode down the line and stopped next to the 31st Illinois of Smith’s brigade. Logan knew the Illinoisans having helped raise the regiment at the start of the war. “We must whip them here or all go under the sod together,” shouted Logan, adding, “Give ‘em Hell!”

A Confederate battery on top of Champion Hill shelled Smith’s men as they swept forward. The Yankees had to cross some high rail fences before they could reach the Alabamians at the bottom of the hill. Smith’s men pitched into the outnumbered Alabamians and with loud cheers drove them back up the hill.

Cumming’s retreat had left Lee’s right flank open, so Lee withdrew his brigade from Champion’s Hill. Several regiments of Barton’s Georgia Brigade on the right subsequently became disorganized as John Stevenson pressed his attack. By 1:30 p.m. the Federals had captured Champion’s Hill. With no fight left in them, Carter Stevenson’s men streamed in full retreat towards the crossings at Baker’s Creek.

Pemberton and his staff rode among the dispirited Georgians in an attempt to rally them. The Confederate commander called for help from division commanders Bowen and Loring, but both refused. Neither liked Pemberton, and they were not going to risk the lives of their soldiers to assist him. Both generals informed Pemberton that they were under too much pressure on their own fronts to come to his assistance. This was not true, though, because neither Osterhaus nor Smith showed any inclination to engage the Confederates in front of them. Pemberton later blamed Loring for not reinforcing the Confederate left on Champion Hill, but if Loring had come to his aid, he would have left the Raymond Road undefended.

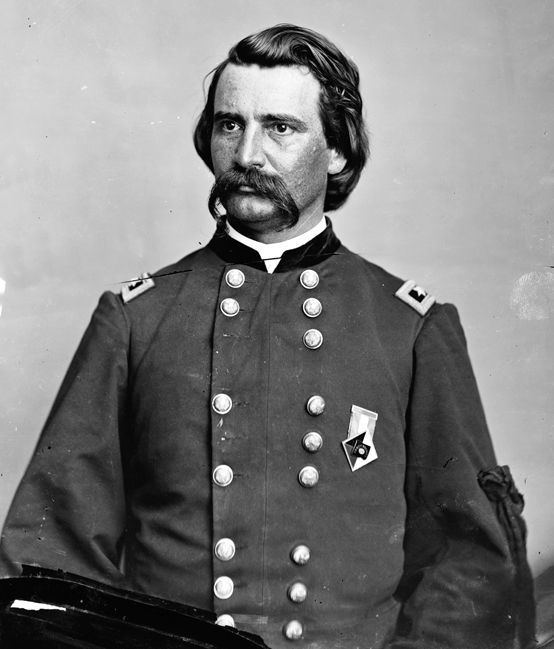

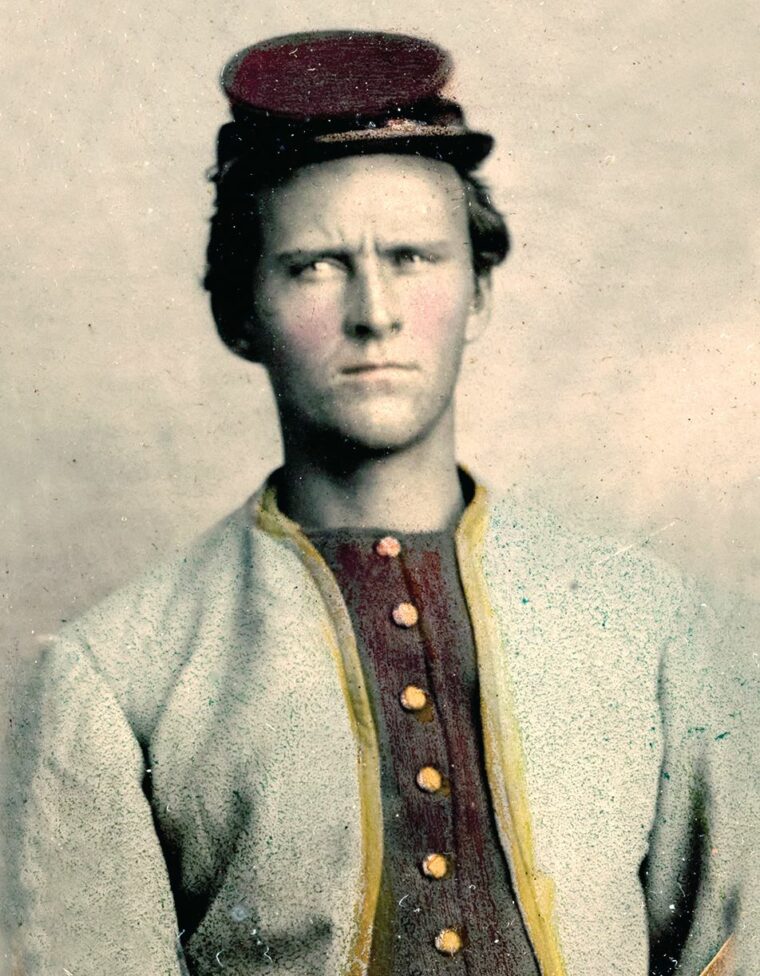

Since his dispatches to his division commanders had not produced any results, Pemberton rode south to see if he could find some fresh troops to assist Carter Stevenson’s exhausted command. Pemberton found Bowen and ordered him to go into action with his two divisions on Stevenson’s right flank. Leaving skirmishers and artillery behind to hold Osterhaus, Brig. Gen. Francis Cockrell, who commanded a brigade of Missourians, and Brig. Gen. Martin Green, who commanded a brigade of Arkansians, maneuvered their rough and ready western troops against Slack’s brigade. Cockrell’s Missourians advanced on the left of Bowen’s line, while Green’s Arkansians pushed forward on the right of Bowen’s line.

These veteran Confederate troops went into action with great determination. On their way to engage the Yankees they passed through the ranks of Cumming’s demoralized Georgians. Cockrell, a colorful personality, rode among his men with his reins and a large magnolia in his left hand and his sword in his right.

As they advanced, a group of Southern women in the yard of Isaac Roberts’ house, which Pemberton had chosen as his battlefield headquarters, sang “Dixie” to the Missourians and Arkansians to cheer them on. “With a shout of defiance and with gleaming bayonets and banners pointing to the front, the grey line leaped forward, and moving at quick-time, across the field, dislodged the enemy,” wrote Colonel Robert S. Bevier of Cockrell’s Brigade.

Bowen’s men charged the Union line on Champion’s Hill at 2:30 p.m. and broke it. In their hurried retreat, the Yankees abandoned many of the Confederate cannon they had fought so hard to capture. Bowen’s men pressed their advantage forcing Hovey’s men back up the Jackson Road to their starting point. It was an amazing feat of arms, considering Bowen’s men received no assistance from any other Confederate regiments. The Federals, however, still had plenty of fight in them. They reformed and once again climbed the steep slope of the hill in a bid to retake the summit. When they were within eight feet of the summit, the Confederates fired well-aimed volleys into their ranks. That section of the Union line collapsed so suddenly, it seemed the entire Union line might crumble and melt away. Stunned by the reverse, the Union soldiers gloomily returned to the base of the hill.

The gallant Southerners, however, soon ran out of ammunition. Carter Stevenson had sent the ammunition supply wagons to the far side of Baker’s Creek in order to prevent the enemy from capturing them. Thus, the gallant Confederate charge that almost split the Union army in half, ground to a halt for want of ammunition. The Confederates on Champion’s Hill began searching through the cartridge boxes of dead and wounded soldiers in a quest to replenish their ammunition. Even so, their advance stopped 300 yards from the Champion House.

afternoon wore on, Pemberton’s army collapsed under the weight of Grant’s superior numbers.

Bowen tried his best to keep the attack going. Pemberton rallied parts of Barton’s and Cumming’s brigades and sent them forward. The reformed troops deployed between the brigades of Cockrell and Green. Lee also sent two of his Alabama regiments to reinforce Bowen’s division with orders to deploy on Cockrell’s left flank.

When the Alabamians began crossing a fence, they came under heavy fire from Captain Samuel De Golyer’s 8th Michigan battery attached to Logan’s division. As the shells exploded among them, the Alabamians withdrew to the refuge of a copse of trees.

Grant and his two corps commanders methodically set about organizing a counterattack. Brig. Gen. Marcellus M. Crocker’s Seventh Division of McPherson’s XVII Corps moved up to threaten the Confederate left flank, and Colonel George B. Boomer’s Third Brigade of Crocker’s Division advanced to plug the breach in the Union center caused by Bowen’s counterattack.

Boomer’s four regiments attacked Bowen’s division, but Green’s Arkansians outflanked Boomer on his left. In a bid to support the Union troops engaged, Hovey massed 16 guns from his three batteries southeast of the Champion House. The Union artillery pounded Green’s men.

Meanwhile, Colonel Samuel A. Holmes Second Brigade of Crocker’s division went into action on Boomer’s right. This checked the Confederate advance. It also bought time for Hovey to reform his troops. Determined to overwhelm Pemberton’s Confederates, Grant brought forward yet another Union brigade to align on Boomer’s right flank. He also shifted John Stevenson’s brigade of Logan’s division from the right to support the Federal center.

The 33rd Illinois of Brig. Gen. William P. Benton’s Brigade advanced rapidly and retook the area lost to the Confederates. Thus, Bowen’s gallant charge ended, and his brave soldiers fell back to the foot of the hill. At that point, most of the men in the 46th Alabama found themselves cut off. With no other recourse left to them, they surrendered.

Bowen then received word that fresh Union troops were threatening his right flank. McClernand had finally put his troops in motion at mid-afternoon after receiving orders from Grant explicitly directing him to advance against the enemy forces in front of him. McClernand in turn ordered Osterhaus to advance on the Middle Road with his two brigades against Bowen’s troops. At the same time, McClernand ordered Smith’s division to move forward along the Raymond Road.

Brig. Gen. Theophilus T. Garrard’s First Brigade spearheaded the advance of Osterhaus’ division. Garrard’s men overran a Confederate picket and came within 500 yards of the crossroads when Osterhaus, who was overseeing the advance, ordered Garrard to stop.

When Bowen pulled his division off the Middle Road, Loring had shifted his troops north to fill the gap. The division held a line 600 yards west of the Coker House. Loring had posted Brig. Gen. Abraham Buford’s brigade on the left, Brig. Gen. Winfield Featherston’s brigade in the center, and Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman’s Brigade on the right. Buford and Featherston blocked the Union advance along the Middle Road, while Tilghman held a strong position on Cotton Hill astride the Raymond Road.

Bowen’s division soon collapsed under the weight of Grant’s powerful counterattack. Arkansians and Missourians joined Georgia and Alabamians already in full retreat towards the bridges spanning Baker’s Creek. Fortunately for the retreating Confederate infantry, Cockrell’s three batteries of artillery maintained a steady fire on Osterhaus’ line, which bought precious time for the battered infantry belonging to Carter Stevenson and John Bowen to make their escape.

With two of his divisions in full retreat, Pemberton continued to search for Loring. As he rode south, he came across Buford. He told Buford to send two regiments to the crossroads and take the rest of his regiments north to defend the Jackson Road. Buford sent the 12th Lousiana and 35th Alabama towards the crossroads with orders to guard against any attempt by the Union forces to capture Cockrell’s guns. Having failed to find Loring, Pemberton returned to his headquarters at the Roberts’ house.

Before leaving the Roberts’ house, he issued orders to his division commanders for a general retreat to the Big Black River. He advised Carter Stevenson and Bowen to withdraw their battered commands to the Raymond Road and lead them across the Lower Bridge over Baker’s Creek.

Major Lockett’s engineers had labored throughout the day to rebuild the Lower Bridge. Fortunately for the Confederates, the water level in the creek had been dropping steadily throughout the day. Indeed, the waters had dropped to such a point that the creek was also fordable in some points near the Raymond Road, thus allowing for the retreating Confederates to cross the creek simultaneously at several places.

Loring rode to the Middle Road where he began deploying his troops for a counterattack to retake the crossroads. But when a member of Pemberton’s staff handed him orders for a general retreat, he broke off his preparations for a counterattack. Pemberton’s orders instructed Loring to cross Baker’s Creek and take up a position at Edward’s Crossing prepared to fight a rearguard action to allow Pemberton’s other two divisions to make it safely back to Vicksburg.

By 4:30 p.m. McPherson’s corps had taken passion of the entire length of the Jackson Road, Champion’s Hill, and the Upper Bridge on Baker’s Creek. On the southern half of the battlefield, McClernand’s corps had secured Ratliff Ridge. From the heights of Champion’s Hill and Ratliff Ridge, Union brigade commanders halted their commands to dress their lines and scoop up hundreds of Confederate soldiers who were at the rear of the disorganized ranks trying to cross Baker’s Creek.

The Union soldiers who had been in the thick of the fight knew they had achieved a great victory, but the heat and exertion involved in fighting in rugged terrain had completely sapped their energy. Although it was clear to them that the majority of Pemberton’s army was in full retreat, they still saw Loring’s three brigades holding an intact line between Ratliff Ridge and Baker’s Creek.

As the Confederates retreated across Baker’s Creek at the Lower Bridge, Tilghman’s Mississippi artillery batteries dueled with Andrew Smith’s divisional guns deployed with Burbridge’s Midwestern infantry. Burbridge sent his sharpshooters to take possession of a group of slave cabins in the intervening ground between the opposing infantry brigades. The Yankee sharpshooters began steadily picking off the soldiers in the front rank of Tilghman’s line of battle. Tilghman ordered the sergeant commanding one of the 12-pounder howitzers to shell the enemy-occupied cabins.

To ensure the rounds hit the targets he desired, Tilghman dismounted and personally sighted the howitzer. As he did so, a Union artillery shell burst near him sending a jagged chunk of shrapnel into his chest. The white-hot chunk of iron passed completely through his body inflicting a fatal wound. Command of the brigade devolved to Colonel Alexander E. Reynolds. Unsure of his responsibilities, Reynolds asked Loring for instructions. The division commander told Reynolds that he was to hold the Raymond Road at all costs.

Meanwhile, Pemberton supervised the passage of the routed Confederates across the creek. When Bowen reached the far side of Baker’s Creek, Pemberton tasked him with reorganizing the remnants of his command in order to cover Loring’s retreat across the creek.

While several of McClernand’s brigades put pressure on Loring’s troops, Loring tried to get his troops across Baker’s Creek. But by the time he was ready to cross, Union artillery had begun shelling the Lower Bridge and adjacent fords. Realizing that he could not get his troops across, Loring led his men south along the east bank of Baker’s Creek in search of another crossing point.

Loring realized after nightfall that he was not likely to find another ford. He therefore resolved to march east to rendezvous with Johnston. The darkness and the muddy condition of the roads compelled Loring to order his troops to abandon the artillery and ordnance wagons. The gunners disabled the cannons, but took the horses and harnesses for future use. Having given up on rejoining Pemberton, Loring led his troops on a roundabout route that took them to Crystal Springs and then north through Jackson to unite with Johnston. The Union army had suffered 2,441 casualties at Champion’s Hill, while the Confederates lost 4,700 killed and wounded and 2,400 captured.

While Loring set off on the night of May 16 to rendezvous with Johnston, Pemberton burned the supplies at Edward’s Station and then struck out with his two battered divisions for Vicksburg. He left three brigades under Bowen to defend the east end of the railroad bridge over the Big Black River on the mistaken assumption that Loring was following close behind him and would need to cross the river quickly.

McClernand’s corps attacked the Confederates who manned breastworks made of cotton bales covered in dirt. The Union troops broke through the weak defenses, routing the Confederates. The victory at Big Black River, in which McClernand captured 1,800 Confederates and 18 guns, gave Grant yet another victory that enhanced the morale of his Army of the Tenneseee and dampened the morale of Pemberton’s dwindling army.

Grant’s troops arrived on the outskirts of Vicksburg on May 19, but formal siege operations did not begin until May 25. Following sustained fighting and bombardment over the course of the next six weeks, Grant compelled Pemberton to surrender on July 4. Unable to take the 30,000 Confederate troops who surrendered into captivity, Grant paroled them. When Port Hudson fell to Union forces five days later, the Union had at last secured the Mississippi River.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments