By Kevin L. Cook

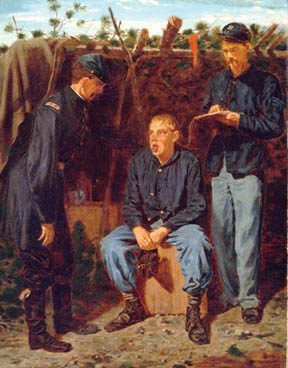

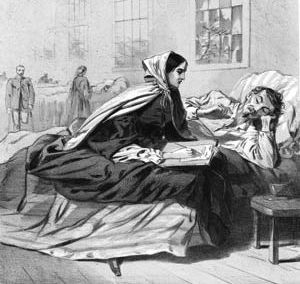

A slight knee wound brought the New Jersey boy to a Washington military hospital, but “his mind had suffered more than his body,” wrote volunteer nurse Louisa May Alcott. “He lay cheering his comrades on, hurrying them back, then counting them as they fell around him, often clutching my arm, to drag me from the vicinity of a bursting shell, or covering up his head to screen himself from a shower of shot; while an incessant stream of defiant shouts, whispered warnings, and broken laments poured from his lips.” Such hallucinations and flashbacks are consistent with what is now called post-traumatic stress disorder.

Symptoms labeled “shell shock” or “combat fatigue” in later wars were poorly understood during the Civil War, and writings of the period imprecisely labeled them “homesickness,” “nostalgia,” “irritable heart,” or sometimes “sunstroke.” Of course, homesick soldiers were not unusual during the war. The very word homesickness had more serious implications than it does today. Kate Cumming, who worked as a nurse in various Confederate hospitals, recounted a concert at which a hospital matron sang “Home, Sweet Home.” It was a mistake, Cumming wrote. “It scarcely does to sing such a song at present, as it touches the heart a little too deeply.” Similarly, Union Surgeon General William A. Hammond wrote that it was often necessary “to prohibit the regimental bands playing airs which could recall or freshen the memories of home.”

Union surgeon John G. Perry said he had attempted to suppress his emotions before he left home, but on the boat headed to the front he had behaved “as I did when a child for the first time away from home. I cried as I did then, all night long.” Perry thought the man in the berth above him was asleep, “when suddenly he rolled over and looked down upon me. I felt for the moment thoroughly ashamed of myself, but he said nothing and settled back into his place, and then I heard him crying also.” Perry said he was haunted by the word home. “An awful sinking at the heart still sweeps over me, and I can easily understand how soldiers die of homesickness.”

A lieutenant with the 3rd Iowa Regiment observed that “many good soldiers were possessed of a homesickness—a desire to be sent home on furlough or discharged, that amounted almost to a mania.” One Union surgeon went even further, claiming that homesickness “killed as many in our army as did the bullets of the enemy.”

A Concern of Both Armies

Concern over homesickness went up the chain of command in both the Union and Confederate armies. In his Confederate surgeon’s manual, Dr. J. Julian Chisolm said that in the Army of Northern Virginia when “homesickness threatened to break out as an epidemic, an order to erect works was always hailed with pleasure.” Even if the fortifications went unused, they were built “simply to keep the men employed, and make them contented and happy.” In 1863, North Carolina Governor Zebulon B. Vance wrote President Jefferson Davis, listing homesickness as one of “the causes which move our troops to quit their colors.”

On the Union side, an official of the United States Sanitary Commission, an organization that supplemented the U.S. Army’s medical and relief efforts, said homesickness was “a great difficulty which our surgeons have to contend with in their patients. Medicines are then useless.” The Government Hospital for the Insane reported that homesickness was “evident by the character of the morbid mental manifestations exhibited by several of our army patients.”

The Symptoms of Nostalgia

Nostalgia was closely related to homesickness. In fact, some writers equated the two. Assistant Surgeon J. Theodore Calhoun wrote in 1864 that nostalgia was merely the more professional term. The Surgeon General’s official history, The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, said that homesickness occasionally “developed to a morbid degree and was reported as nostalgia.”

Official figures for nostalgia cases were not large—5,547 cases, 74 deaths, and 36 discharges through June 1866—making the malady less prevalent than epilepsy, for example. However, Assistant Surgeon Roberts Bartholow said, “These numbers scarcely express the full extent to which nostalgia influenced the sickness and mortality of the army.” Bartholow, who wrote the surgeon general’s manual for soldier enlistment and discharge, said nostalgia was frequently fatal and was “a ground for discharge if sufficiently decided and pronounced.” Calhoun saw nostalgia often as a cause of other disease, or as a “complication to be dreaded as one of the most serious that could befall the patient.”

Symptoms attributed to nostalgia varied from doctor to doctor. Bartholow listed “weeping, sighing, groaning, and a constant yearning for home; hallucinations and sometimes maniacal delirium.” Dr. Samuel D. Gross, a professor of surgery, said nostalgia was “characterized by a love of solitude, a vacant, stultified expression of the countenance, a morose, peevish disposition, absence of mind, pallor of the cheeks; and progressive emaciation.”

Assistant Surgeon De Witt C. Peters noted that early symptoms included great mental dejection, loss of appetite, and indifference to external influences. These gave way to hysterical weeping, throbbing of the temporal arteries, an anxious expression of the face, and “watchfulness,” among other symptoms. Another surgeon referred to “impaired digestion and prostration of nerve-power manifested by languor, tremulousness, palpitations and obscure cardiac pains.”

Peters said that among young prisoners of war, nostalgia was the worst complication to encounter. Anna Holstein, a volunteer nurse, had experienced the condition with former prisoners. A Union soldier under her care became frantic with terror. When asked if the flags on the walls looked like Rebel flags to him, the soldier replied, “Oh, no, that looks like home.”

Treating Nostalgia

There was no agreement on how to treat nostalgia patients. Calhoun recalled his boarding school days, where ridicule was wholly relied upon. “The patient can often be laughed out of it by his comrades, or reasoned out of it by appeals to his manhood,” wrote Calhoun, “but of all potent agents, an active campaign, with its attendant marches, and more particularly its battles, is the best curative.” As evidence, he discussed a unit that lost men daily in camp while adjacent regiments remained healthy. Actively engaged at the Battle Chancellorsville, however, they fought nobly, developed a strong esprit de corps, “and from that day to this, there has been but little or no sickness, and but two or three deaths.”

Similarly, Surgeon John L. Taylor noted that “kind and sympathizing words—amusements—seemed to invite a more deplorable condition.” That approach predominated in his regiment, whose officers told soldiers that their disease was merely moral turpitude, looked upon with contempt, and that “soldiers of courage, patriotism and sense should be superior to the influences that brought about their condition.” Taylor claimed better success with his method. “This course incited resentment, passions were aroused, a new life was instilled and the patients rapidly recovered,” he said.

In sharp contrast, Gross argued for more sympathy and less criticism. “The treatment is moral rather than medical,” he advised, “agreeable amusements, kindness, gentle but incessant occupation, and the promise of an early return to home and friends constituting the most important means of relief.”

Another surgeon’s view was to give the troops something to do to pass the dull hours. “An officer should be detailed as Superintendent of Public Amusements, who should be manager of theatrical performances, races, competitive shooting and prize competitions of all sorts.” Ultimately, such treatments may say more about the surgeon than about the patient or disease.

Cases of an “Irritable Heart”

Some surgeons noted heart-related symptoms in nostalgia patients early in the war. In 1862, Surgeon A.J. McKelway reported heart disease caused by “overexertion preceding the battle and excitement and effort during its continuance.” With the benefit of two decades of hindsight, the surgeon general’s history observed: “Overaction of the heart during an engagement was due perhaps as much to nervous excitement and anticipation of danger as to overexertion. Even soldiers accustomed to the alarms of battle were not at all times exempt from the results of mental impressions.” Many cases arrived in hospitals after the continued exertion, anxieties, and excitement. Some patients experienced acute chest pain even while asleep.

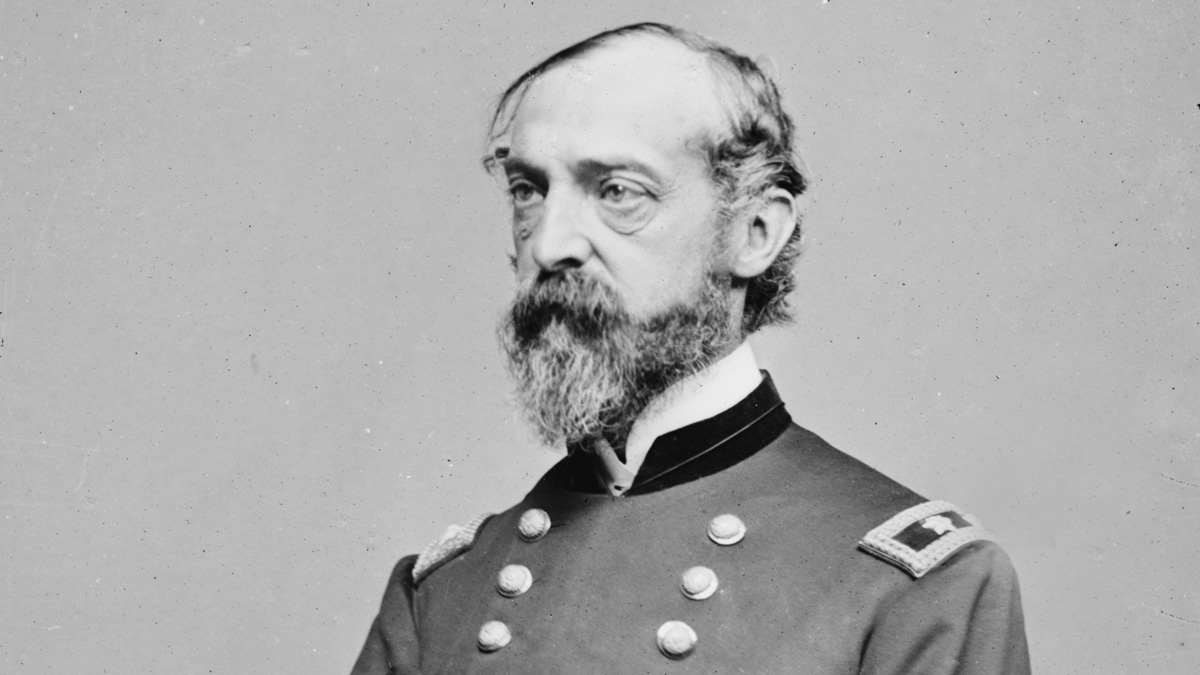

Most Civil War surgeons did not make the now obvious connection between heart disease and stress. In late 1862, Acting Assistant Surgeon Jacob M. Da Costa reported an uncommon malady, called “Chickahominy fever,” among soldiers returning from Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s just concluded Peninsula Campaign. “Both body and mind remain for a considerable period enfeebled,” noted Da Costa. Symptoms included memory loss and “mental wandering.” Another surgeon listed such symptoms as “indifferentism, wandering and muttering, restlessness, insomnia, and watchfulness.”

Da Costa described typical cases with heart-related symptoms, including “palpitation and a feeling of uneasiness in the cardiac region.” Another patient had palpitations and sharp chest pains. The patient’s other symptoms improved and he regained his strength, “but any excitement or labor agitates him and brings on violent beating of the heart,” Da Costa observed. “The irritable state of the organ remaining long after the general health was in every other respect fully reestablished, all form a clinical combination of very great interest and frequency.”

In early 1863, Dr. Alfred Stillé, who worked at a large military hospital in Philadelphia, reported heart palpitations to be a common disease among the soldiers, in a form he had very rarely observed in civil practice. Stille associated it with “a state of extreme exhaustion, especially when occurring after violent and prolonged muscular efforts.” A few months later, Dr. Henry Hartshorne noted among his patients, similar palpitations, which he evocatively called “trotting heart” or “cardiac muscular exhaustion.” Hartshorne recognized nervousness as a source of palpitations but found the soldiers’ palpitations to differ in character from “ordinary sympathetic or nervous palpitation” in his civilian patients.

Da Costa used the phrase “irritable heart” in the title of an 1871 journal article in which he summed up his experience with more than 300 soldiers and continued to define it as a functional cardiac disorder. Besides palpitations, sometimes violent, Da Costa noted that his patients suffered from “smothering or suffocating sensations at night, a mere feeling of uneasiness near the heart, shortness of breath, giddiness, and disturbed sleep, including dreams of unpleasant character.”

Da Costa attributed a plurality, some 38.5 percent, of the cases to hard field service, particularly excessive marching. Within this category he included constant and heavy duty on the picket line, active movements in the face of an enemy, forced marches, and arduous and exciting fighting and marching. It was entirely opposite from other physicians’ positive interpretation of battle-related activities during the war.

In contrast to an overall lack of treatment for mental disease, there were some treatments in place for heart disease. Da Costa first prescribed rest but also employed plant-based remedies, including digitalis, aconite, veratrum viride, gelsemium, hyoscyamus (henbane), belladonna and atropine, conium (hemlock), and Cannabis indica.

The Trouble With Treatment

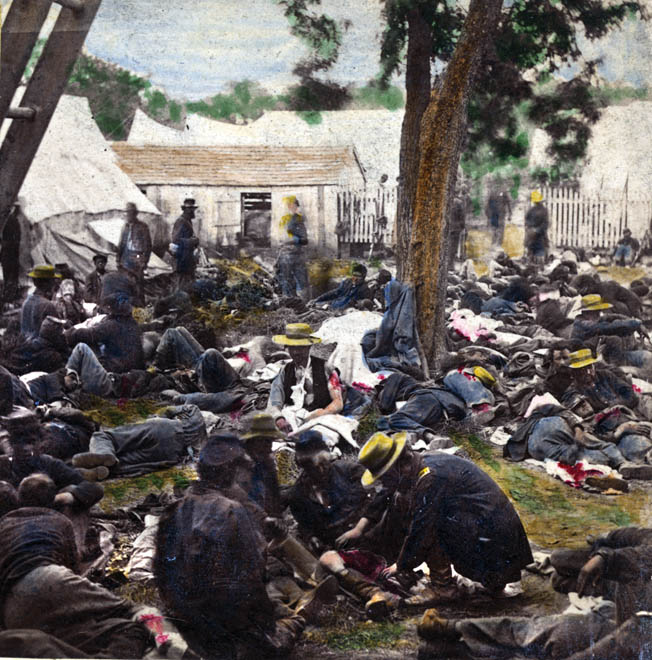

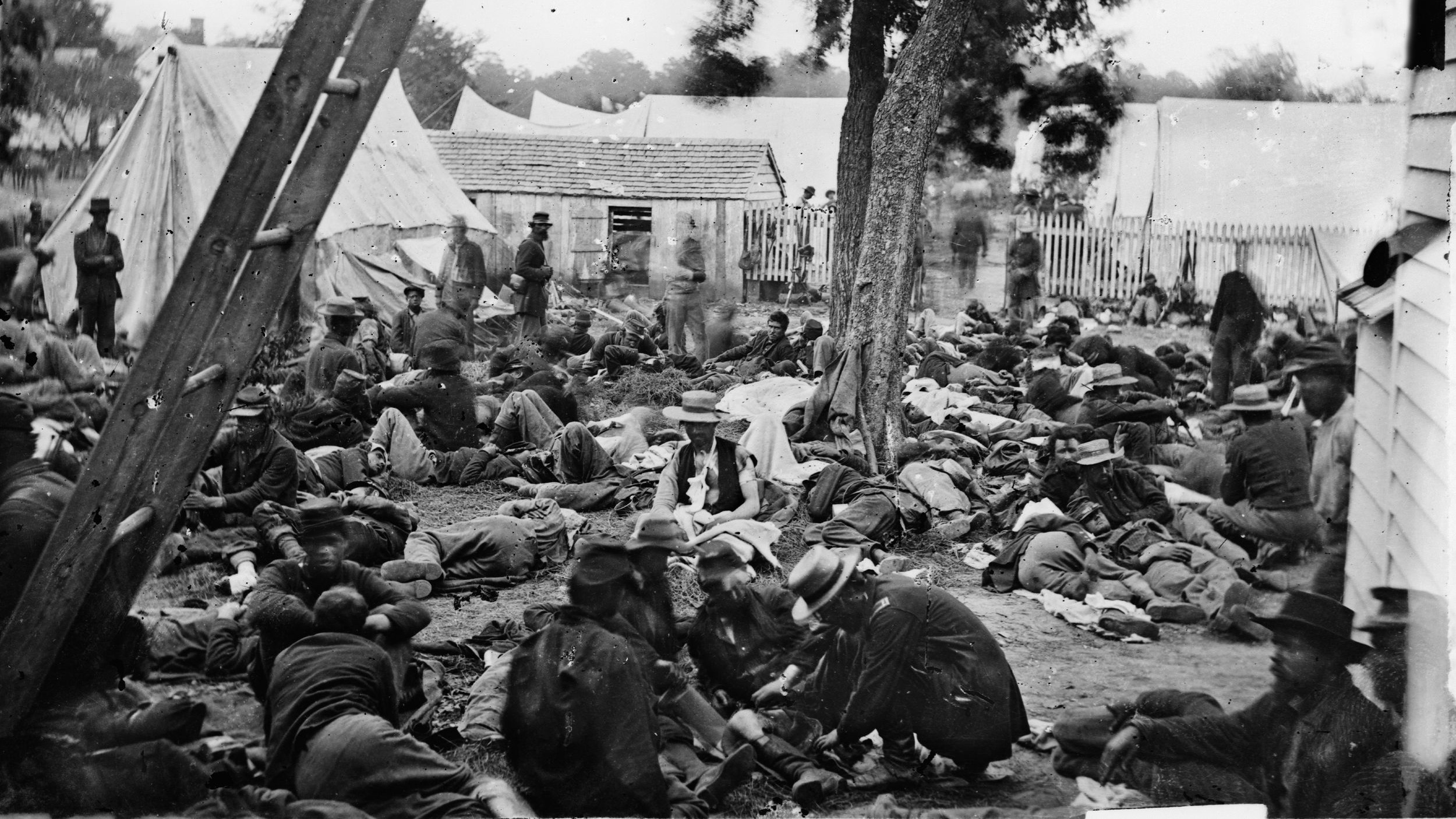

Massive numbers of casualties made effective or even humane treatment difficult. Julia Wheelock worked in Washington-area hospitals from 1862 through 1865. She estimated that there were 10,000 wounded in Fredericksburg, Virginia, at one time. All the public buildings, including the courthouse, churches, hotels, warehouses, factories, paper mill, theater, school buildings, stores, stables, and private residences were converted into shelters for the wounded, until Fredericksburg was one vast hospital.

Wheelock recounted wounded soldiers begging for pillows. “I’m wounded in the head, and my knapsack is so hard,” said one. Another wanted one for his stump. “I don’t think it would be so painful if I only had a pillow, or cushion, or something to keep it from the hard floor,” the soldier said. One “wretched hospital,” a former grocery store, had only a single small candle for light. When someone moved the candle to another part of the crowded room, Wheelock, afraid she would stumble over the injured, crept on her hands and knees to deliver cups of broth to the wounded, starving soldiers. Many were so fresh from the battlefield that their wounds were still undressed. Given such conditions, it was small wonder that the often overwhelmed military medical establishment could not care adequately for victims with poorly understood psychological needs.

In 1855, Congress had established in Washington the Government Hospital for the Insane, later St. Elizabeth’s Hospital. Its stated goals were to provide “the most humane care and enlightened curative treatment of the insane of the army and navy of the United States, and of the District of Columbia.” Diversions of the mind were found to displace morbid feelings. Such diversions included church services, educational lectures, music, books, and musical instruments, including several pianos. Caregivers attempted “to render the institution not only a good hospital, but a kind and sympathizing home.”

Recovering After War

After the Civil War, Congress liberalized the law governing admissions to the hospital. Those accepted included former patients who relapsed within three years of their discharge from the hospital, those discharged from the military for insanity, and “indigent insane persons, who have become insane within three years after discharge from such service from causes which arose and were produced by said service.” Giving veterans three years after discharge to seek treatment was a relatively forward-looking admission that mental and emotional wounds, like physical wounds, could take years to heal.

Some wounds never healed. A 2006 study of military and Pension Board medical records of 17,700 Civil War veterans found an association between the men’s wartime experiences and the occurrence of cardiac, gastrointestinal, and nervous diseases throughout the remainder of their lives. One measure found a 51 percent increase in those three disease categories.

Those removed from the battlefield were marked by their experiences as well. A civilian relief worker wrote that after the Battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania, “The surgeons were at work, probing, extracting balls, amputating in the open air, while upon every hand were cries of agony from the poor fellows, which would have melted any but a heart of stone.” Years later, nurse Lois Dunbar recalled, “I have had men die clutching my dress till it was almost impossible to loose their hold.” Even experienced doctors and nurses could not easily forget such sights and sounds.

One soldier summed up the literal deadliness of nostalgia: “Would you believe—and yet it is true—that many a poor fellow in the Army of the Cumberland has literally died to go home; died of the terrible, unsatisfied longing, home-sickness?” Against the ravages of nostalgia, he wrote, paraphrasing Shakespeare’s Macbeth, “the surgeon combats in vain, for, ‘who can minister to a mind diseased?’” Sadly, the answer to Macbeth’s rhetorical question remained largely true 2½ centuries later, during the Civil War. “Therein the patient must minister to himself.” For many soldiers, as for the guilt-stricken Macbeth, there was no cure at all.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments