By Victor Kamenir

Russian historical documents dating back to 1095 speak of an unknown people living beyond the Ural Mountains in Siberia who spoke an incomprehensible language and traded furs for iron knives and axes. The ermine, marten, and fox traded by the Siberian natives found ready and lucrative trade on the European markets. The most valuable fur was that of the sable, a species of marten.

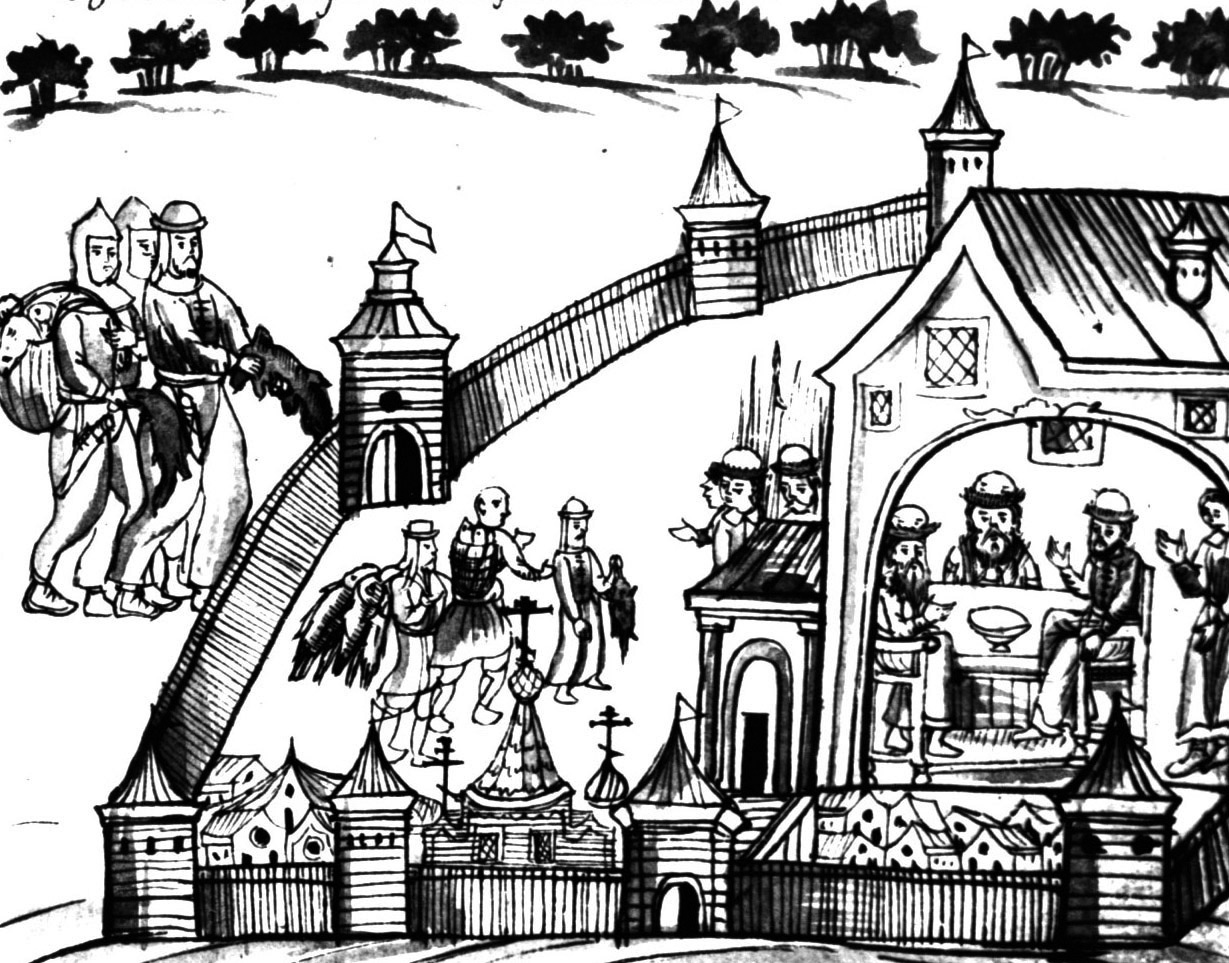

Following the source of furs, trappers and merchants from the city-state of Novgorod developed an eastern route along inland waterways that skirted the Ural Mountains to avoid the unfriendly Bulgars and Tatars. By the beginning of the 12th century, Novgorod fought several campaigns to subjugate the peoples of Ugra, as the northern Trans-Urals was called, in order to expand its lucrative trade in luxury furs. Whether by force of arms or by negotiations, the native tribes were obligated to pay yasak—a Turkic word for tribute used in imperial Russia—which was collected in furs.

Although a major trade hub, Novgorod’s influence and power gradually waned as a result of its protracted struggle with the Grand Duchy of Moscow. In 1478, Grand Prince of Moscow Ivan III forcibly annexed Novgorod. In addition to absorbing Novgorod’s territory, Moscow inherited Novgorod’s profitable fur trade, which became a major source of income for Moscow’s treasury. In their insatiable quest for more furs and trade routes, Muscovites continued Novgorod’s push to the east.

The most accessible route to north-central Asia ran through the southern ranges of the Urals. Beginning with the Kama River in the Perm region, the route ran through a network of smaller rivers and portages that connected with the great Irtysh River. The Irtysh, which drained most of West Siberia, originated in the Altai Mountains and flowed north to the Ob River, which emptied into the Arctic Ocean.

But the hostile Khanate of Kazan, a Tatar Turkic successor state of the Mongol Golden Horde, controlled the route. A weaker Tatar state, the Khanate of Sibir, was situated further east. Tsar Ivan IV, commonly known as Ivan the Terrible, defeated the Kazan Khanate in 1552. Fearing the same fate, Khan Yadegar, who ruled the Sibir Khanate, dispatched an embassy to Moscow in 1555. His emissaries shared the khan’s request for protection and pledged tribute to Ivan. The tsar, in turn, promised to defend the Sibir people of southwestern Siberia and welcomed their tribute in furs.

Because he had committed a large number of Russian forces beginning in 1558 in an attempt to conquer Livonia, the tsar lacked the manpower and resources to personally lead a march of conquest to the western foothills of the Ural Mountains. Instead, he trusted the expedition to Grigorii Stroganov, who was a senior member of the influential Stroganov merchant family.

The tsar granted the Stroganovs a patent on April 4, 1558, to exploit the lands along the Kama River, a left tributary of the Volga River. “[The Stroganovs] may build a small town in the black forest, in a secure and well-protected location, and emplace cannon and defense guns in that town, and I authorize him, at his own expense to station cannoneers and gunners and gate guards there to protect the town from the Nogai people and other hordes,” Ivan wrote. The patent gave Stroganov the right to cut timber, plough arable lands, and establish farmsteads. It also empowered him to invite unregistered, nontax-paying persons to settle in the towns they established.

The Stroganovs found salt deposits in the Perm area. They mined salt for a domestic market and sent back furs for Russia’s foreign trade. It was not long before they commanded the largest commercial enterprise in Russia. Eager to take advantage of the opportunity that the tsar’s patent embodied, the Stroganovs steadily advanced east. In the course of their advance, they built settlements, established commercial enterprises, and traded with the natives for furs.

The Stroganovs’ relentless expansion placed them in direct conflict with the Sibir Khanate. Whereas the Perm region was on the west side of the Ural Mountains, the Khanate of Sibir was situated just over the Urals on the east side of the mountains.

The arrangements made by the Siberian ruler with the Russian tsar in 1555 did not last long. There were tensions in the Sibir Khanate between the rival Taibugid and Shaybanid clans. Kuchum, the Muslim chieftain of the rival Shaybanid clan and a direct descendent of Genghis Khan, desired to rule Siber. With the assistance of the Crimean Nogai Tatars, Kuchum killed Yadegar in 1563 and made himself the Khan of Siber. Tsar Ivan had never given Yadegar any protection from his enemies because the slain khan had failed to deliver the full sum of tribute that he had proposed to the tsar eight years earlier.

While Russia engaged in the protracted Livonian War on it western frontier, the Nogai Tatars in 1571 invaded the Russian empire from the south. They advanced all of the way to Moscow. When they set fire to the suburbs of Moscow on May 24, high winds blew it into the city, resulting in a conflagration.

Taking advantage of the disarray in the Tsardom of Russia, Kuchum stopped paying the tribute. The following year, he murdered the Russian ambassador and broke off relations with Russia. Kuchum then sent his nephew, Mametkul, to plunder Russian territory on the west side of the Urals.

In response to the depredations orchestrated by Kuchum, Tsar Ivan IV authorized the Stroganovs to prepare for war against the Sibirs. “[Recruit] as many Cossack volunteers as you can call upon, all well-armed with every manner of weapon from guns to bows and arrows,” Ivan wrote.

Mametkul began raiding Stroganov territory along the Chusovaya River in 1573. The raiding parties burned villages and killed trappers and settlers. They also forced local Ostyak and Vogul tribes, who lived on both sides of the Urals, to join forces with the Khanate of Sibir and pay tribute to Kuchum.

The Stroganovs complained loudly about the growing menace to the tsar. “The Voguls live near our villages; the terrain is wooded, and they will not let our people and peasants to leave their forts, nor allow them to tend their crops nor to cut wood,” they wrote. “And these petty people come to steal; they drive away our horses and cows and kill our people. They ruin our industry in the villages and won’t let us pan salt.”

The Stroganovs requested that Ivan IV grant them additional rights to explore eastward and impose order on areas they occupied beyond Russia’s eastern frontier. The tsar agreed and issued a new charter in 1575 that allowed the Stroganovs to wage war against hostile tribes who invaded their lands and were the subjects of Khan Kuchum.

The tsar had previously suggested that the Stroganoffs should consider employing Cossacks under a dependable leader to protect their lands and commercial interests. Finally heeding the tsar’s advice, the Stroganov’s hired Cossack ataman (chieftain) Yermak Timofeyevich in 1579 to help defend their lands and businesses. Yermak had commanded a Cossack contingent in the Russian army during the Livonian War.

Yermak returned to his homeland in the Volga region as the long war in Livonia was nearing its conclusion. He and his band of Cossacks, who no longer could draw government pay as soldiers, began searching for new sources of income.

For the first two years of his employment, Yermak and his band of Cossack soldiers defended the Stroganov lands from incursions by Tatars, Cheremis, Ostyak, and Vogul tribesmen, who plundered their lands and carried off women and children to be slaves.

The Stroganovs had set their sights on eastward expansion beyond the Urals to extract natural resources from Siberia. Russian prospectors had located deposits of silver and iron ore just east of the Urals along the Tura River, and it was believed that the same area included sulfur, lead, and tin.

A popular and charismatic leader, Yermak cobbled together a small army of Cossacks and joined forces with atamans Ivan Koltso and Bogdan Briazga. The shrewd Stroganovs directed Yermak to undertake an expedition against Kuchum, describing riches to be had beyond the Urals. Maksim Stroganov, another senior member of the family, agreed to provide the Cossacks with supplies, but tried to get them to pay for the provisions.

The angry Cossacks came close to lynching him, with Ivan Koltso threatening to shoot Stroganov where he stood. Sufficiently cowed by the Cossacks, Stroganov furnished them with supplies needed for the expedition for free. In addition, the Stroganovs added 50 of their own armed retainers, as well as guides and interpreters, to Yermak’s band.

The Stroganovs compensated the Cossacks handsomely. “[They] outfitted them with fine clothing and cannon, volley guns, seven-barreled muskets, and provisions in abundance,” according to the Stroganov Chronicle. In addition, the merchant family furnished Yermak and his men with flat-bottomed river craft known as doshchaniks. These wooden boats could be rowed with oars, towed from the shore, or mounted with a sail. They could transport 20 men, as well as their weapons and supplies.

Much of the knowledge concerning Yermak’s campaigns and other events involving the Russian conquest of Siberia are contained in several dozen works written from the late 16th through the 18th century known collectively as the Siberian Chronicles. In addition to the Stroganov Chronicle, other important chronicles are the Yesipov, Kungursk, Pogodin, and Remezov. The chronicles are complex and, while essential to understanding the period, they contain some apocryphal and contradictory information.

Having suffered from Tatar raids for years, the Stroganovs were aware of the military potential of the Khanate of Sibir, which had a core force of approximately 3,000 experienced Tatar horsemen. The Russian Ambassadorial Bureau estimated the total male population of the khanate at 40,000 souls, and it was rumored that Kuchum could field as many as 10,000 armed men. Although this number is almost certainly an exaggeration, the Ostyak and Vogul levies could add at least 1,000 warriors to Kuchum’s host.

It was unlikely that the Stroganovs counted on Yermak and his men to conquer the Khanate of Sibir, but any foray by a band as strong as Yermak’s would certainly relieve pressure on Stroganovs’ territory. Yermak planned a swift raid by his Cossacks against Isker, the capital of the Sibir Khanate, before the rivers froze in late autumn. The Stroganov guides, familiar with the river network in the Ural Mountains, advised Yermak that the best time to cross the Urals would be in early September, when the autumn rains raised the water in the rivers substantially, thereby allowing the men to freely navigate their doshchaniks.

Yermak and his small force embarked on their journey east on September 1, 1582. His band consisted of 540 Cossacks, as well as 300 prisoners of war from the Livonian conflict that served as porters. The expedition traveled by boat up the Kama River to the Chusovaya River. The Cossacks had to contend with strong currents and rapids on the boulder-studded Chusovaya River. Entering the Serebryanka River, they continued to the Chuili River, from where they conducted a portage with their boats to the Zhuravl River. Putting their boats in the water once again, they entered the Baranch River, followed by the Tigil and Tura rivers. The last river they reached was the Tobol, where the Khanate of Sibir had been founded.

The first clash with the natives took place near the modern town of Turinsk on the Tura River, where Vogul ataman Yepancha had gathered his warriors. Disembarking from their boats, the Cossacks engaged Yepancha. In reply to Vogul arrows, the Cossacks fired several volleys from their muskets and then closed with cold steel. Dispersing the Voguls, the Cossacks looted Yepancha’s settlement. “They killed many infidels whom they overcame with God’s help,” states the Remezov Chronicle. “And they took so much booty that the boats could not carry it, so they buried these possessions in the ground at the mouth of the river Tura.”

Yepancha promptly reported to Kuchum of the approach of the Cossacks. Having won a string of victories over the Ostyak and Vogul tribes, Kuchum was confident that his forces could resist the Cossacks. Kuchum incorrectly surmised that the Cossacks were sent by the tsar, which meant the Russians would have had to strip their garrisons of men in the Perm region to form the expedition. If this were the case, then Perm would be practically undefended. Taking advantage of the situation as he perceived it, Kuchum sent his son and heir Prince Ali with his best troops to attack the Perm region. Ali’s force travelled to the Urals by the northern route, skirting around Yermak’s advance.

With the Cossacks rapidly approaching Isker in their light river boats, Kuchum gathered his Tatar warriors, as well as Ostyak and Vogul levies near the Chuvash Cape, and built a barrier of mud and tree trunks across the Irtysh River. Additional earthworks were thrown up on the shore, where Mametkul commanded the forces arrayed against Yermak. All the while, Kuchum watched the events unfold from the safety of a nearby height. Seeing the great host assembled before them, some of the Cossacks wanted to retreat, but Yermak would not hear of it. He knew all too well that a retreat would encourage Kuchum to attack. He therefore decided to attack the Tatars.

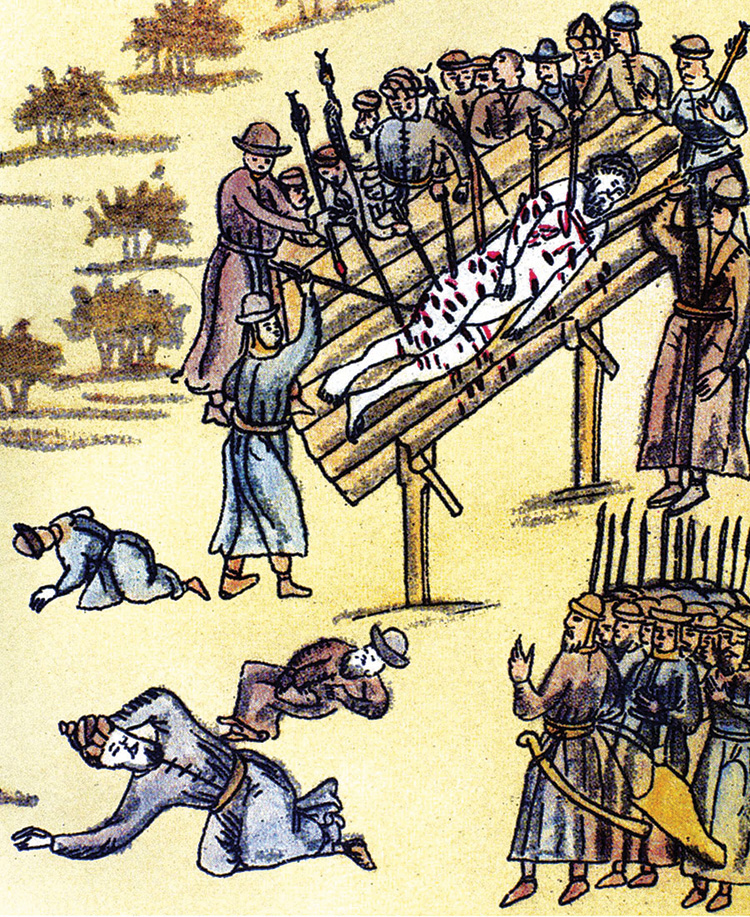

Disembarking from their boats, the Cossacks advanced against Mametkul. They stormed the earthworks twice, but the Tatars hurled them back both times. Seeing the Cossacks falling back, Mametkul led his Tatar warriors forward. After absorbing volleys from Cossack firearms, the Tatars closed in to decide the matter with cold steel. Yermak rallied his men, and in the ensuing melee, Mametkul fell wounded from his horse and was taken away by his loyal warriors. When they saw Mametkul fall, the Tatars wavered. Worse still, their Ostyak and Vogul allies fled the field. The pursuing Cossacks reached the earthworks. Once at the earthworks, they overpowered the Tatars in hand-to-hand fighting and drove them from their entrenched position.

“The pagans shot innumerable arrows, and against them the Cossacks fired from fire-breathing muskets, and there was dire slaughter; in hand-to-hand fighting they cut each other down,” states the Yesipov Chronicle. Although the Cossacks won, it was a Pyrrhic victory, for 100 Cossacks lay dead; of those who survived, almost no one escaped without a wound.

Seeing his warriors retreating, Kuchum rushed to Isker. Gathering his treasures, the khan abandoned his capital, and the town’s residents followed him in flight. Yermak and his Cossacks entered Isker unopposed on October 20, 1582. Yermak’s swift raid against Khan Kuchum had succeeded, but it was too late for the Cossacks to return to Perm given that the rivers had already frozen.

Several days after the Cossacks entered Isker, a local Vogul prince arrived with gifts and provisions and pledging his obeisance to the Russian tsar. Seeing that this prince and his men were unmolested, the town’s residents began returning.

The Cossacks had difficulty wintering in the region. There was constant skirmishing with Mametkul troops. Nevertheless, Cossack parties were able to raid along the Irtysh River, collecting tribute and coaxing local princes into swearing allegiance to the tsar. While the Ostyak and Vogul nobles for the most part submitted willingly, the Tatar nobles in the villages near Isker resisted the Cossacks.

Ataman Briazga slaughtered the local nobles in one of the villages in order to compel others to submit. “[He] collected tribute with drawn sword, and then laying the sword on the table told them to pledge loyalty to the sovereign tsar, serve him, and pay tribute for all years, and not betray him,” states the Kungursk Chronicle. Briazga then continued down the Irtysh River, collecting tribute from Ostyak tribes, but with less violence.

Supplies grew scarce in Isker as the winter dragged on. The Cossacks, who had acquired horses, conducted mounted forays into the countryside in search of provisions. One detachment of Cossacks arrived at a fortified encampment on the Demyanka River, which was controlled by Tatar ataman Nimnyuian. The ataman assembled a large force of Tatars, Ostyaks, and Voguls to resist the Cossacks. The Cossacks repeatedly assaulted the encampment over the course of three days but were unable to breach its defenses. Briazga eventually arrived with reinforcements that tipped the odds in favor of the Cossacks. With the additional troops, the Cossacks succeed in capturing the settlement.

While the Cossacks were establishing themselves in Isker, Prince Ali and his warriors arrived before Russia’s Fort Cherdy in the Perm region. After an unsuccessful attempt at storming the fort, Ali destroyed several nearby villages before returning to Sibir.

While waiting for Ali to return, Kuchum gathered another strong force of 3,000 men under Mametkul to retake Isker. Taking the fight to the enemy once again, Yermak engaged the Tatars on December 5, at Lake Abalak, which was situated 10 miles from Isker. The fight was bloodier than at the Chuvash Cape and lasted all day. The fighting ended at nightfall, and the Tatars withdrew under cover of darkness. The Cossacks’ losses were heavy, losing men Yermak could ill afford.

Another detachment under Briazga sailed down the Irtysh River in spring 1583. The Tatars ambushed the Cossacks in a narrow gorge. The Tatars approached the Cossacks on rafts and tried to board their boats by throwing grappling hooks, but the Cossacks fired a heavy volley that dispersed the attackers. Continuing along the Irtysh River, Briazga reached the Ob River, where he collected tribute and accepted the submission of the local tribes.

At that time, the Cossacks experienced discontent in their ranks owing in part to the harsh winter they had been through. With their ranks steadily dwindling, many of the Cossacks wanted to return to Russia with the great store of booty they had accumulated. But Yermak decided to stay in Isker. In an effort to replenish his ranks, he sent one of his principal lieutenants, ataman Cherkas Aleksandrov, with 25 men to Moscow to make a personal appeal to the tsar for aid.

Reaching Moscow in autumn 1583, Aleksandrov and his men were full of apprehension, for they were unsure of how the tsar would react to their unauthorized expedition. To their surprise, Ivan IV expressed his pleasure when he learned of their exploits and their acquisition. He rewarded the members of the delegation with cloth and money and arranged for gold to be sent to Yermak and the other Cossack atamans. But he instructed Aleksandrov to tell Yermak that the tsar requested his presence in Moscow. The tsar wanted to present an additional gift to Yermak. Although there is no official record of the gift, it is believed that the tsar gave Yermak two suits of armor.

After Aleksandrov’s departure, Tsar Ivan IV ordered preparations to be made for the spring 1584 campaign. The expedition commander Prince Semyon Bolkhovskii was to be accompanied by captains Ivan Kireev and Ivan Vasiliev Glukhov. Their force was to consist of 300 troops recruited from various regions such as Kazan, Sviiazhsk, Perm, and Viatka. The tsar also instructed the Stroganovs to furnish them with boats to transport their supplies.

The tsar died on March 28, 1584, and was succeeded two months later by his son, Fyodor. The new tsar was both physically weak and mentally deficient, and his wife’s brother, Boris Godunov, managed the affairs of state.

The Cossacks inflicted multiple defeats on Kuchum’s troops in 1584. These victories emboldened local tribal chiefs who were secretly hostile to Kuchum. One of the Tatar nobles, Senbakhta Tagin, who was a key rival of Mametkul, informed the Cossacks that Mametkul’s camp was located on the Vagai River, 60 miles from Isker. Yermak immediately sent a strong detachment. The Cossack force attacked the Tatar camp under cover of night, inflicting heavy casualties on it and capturing Mametkul. The Cossacks eventually brought Mametkul to Moscow in 1585, where he pledged allegiance to Tsar Fyodor. Entering the Russian service, Mametkul fought with distinction during the Russo-Swedish War of 1590-1595 and in the 1598 campaign against the Crimean Tatars.

Mametkul’s capture further emboldened Kuchum’s enemies. He’d lost his best commander and the support of Mametkul’s warriors, and even his closest advisors and nobles began deserting him. Sensing Kuchum’s weakness, Seid-Khan, the nephew of murdered Khan Yadegar, returned to Siberia from his exile in Bukhara determined to get revenge. With his base of power eroded, Kuchum gathered forces still loyal to him and retreated to the eastern portion of the Khanate.

Unbeknownst to Kuchum, Yermak was experiencing difficulties of his own. His campaign up to that point had cost him many men. What is more, Cossack supplies of gunpowder and bullets were nearly exhausted, so many of the Cossacks opted to return to Russia. Anticipating a possible withdrawal from Isker, Yermak decided in 1584 to conduct a campaign in the Pelym region of the Sibir Khanate, which was the closest section of the realm to the Urals, in order to secure his lines of communications back to Russia.

Yermak’s force moved at rapid pace. The Vogul tribes in the Pelym region around the Tavda River largely remained loyal to Kuchum, and Yermak wanted to destroy the threat the Voguls in Pelym posed to his Cossack band. The Voguls put up a fierce resistance. With their ammunition and gunpowder almost completely exhausted, the Cossacks engaged their enemy with swords. In one engagement, Cossack ataman Nikita Pan and his small force was wiped out. Altogether, the Pelym campaign cost Yermak 39 men.

The capital of Pelym, a town by the same name, was located on a fortified hill, and its ruler, Amir Aplygerim, could muster 700 warriors. Approaching Pelym, Yermak looked despondently on its strong defenses. Attacking Pelym would cost Yermak losses that he could ill afford, and therefore he returned to Isker.

Shortly after Yermak returned to Isker, the Russian detachment under Prince Semen Bolkhovskii arrived late in 1584. Setting off on their campaign, the soldiers carried their provisions with them. During the delays they encountered crossing the Ural Mountains, the soldiers consumed their supplies. As a result, they arrived in Isker tired and hungry. Worse still, they lacked winter clothing. The soldiers were expected to live off the land, but they could not do so in the hostile Pelym region.

The Cossacks living in Isker had sufficient quarters, but they had no knowledge of Bolkhovskii being sent to assist them or that they were to billet the soldiers. Moreover, there were only enough provisions in town for the Cossacks. The winter of 1584-1585 was brutal, with temperatures far colder than normal.

“These men sent with the [commander] Prince Semen Bolkhovskii, and with the captains, were Kazan and Sviiazhsk fusiliers, and men from Perm and Viatka,” states the Pogodin Chronicle. “They had no supplies at all, and all these men who were sent … perished in the Old Siberia from hunger.”

But the dead soldiers left behind their weapons, gunpowder, and ammunition. Even though Yermak’s strength by then was fewer than 200 men, he could still fight with fresh supplies. Bolkhovskii also brought the tsar’s orders for Yermak to come to Moscow, but after Bolkhovskii’s death, Yermak simply ignored the orders.

Yermak tried to avoid losing more men and was amenable to peace overtures from Tatar nobles. One of them was Ataman Karacha, who’d previously broken with Kuchum and established himself on the Tara River. Karacha offered friendship to Yermak and requested a Cossack detachment to accompany him for protection from his enemies.

Yermak sent Ataman Ivan Koltso with 40 soldiers to assist Karacha; however, immediately upon their arrival in Karacha’s camp, the Tatars ambushed and killed the Cossacks. The victory encouraged other Tatar nobles to rise up against the Cossacks. As a result, several small groups of Cossacks who were collecting tribute and supplies were wiped out.

A large force of Tatars under Karacha surrounded Isker in spring 1585. Karacha established a tight cordon around the town and prevented those still loyal to Yermak from bringing in supplies.

A small force under Ataman Matvei Mescheryak sallied forth one night from Isker and caught Karacha’s men by surprise. They slew many, but Karacha escaped. The following morning, Karacha rallied the rest of the Tatars besieging Isker. As a result, Mescheryak found his force encircled. Taking up positions behind bushes and trees, the Cossacks fired withering volleys from their muskets. Unable to match their firepower, Karacha raised his siege of Isker and withdrew from the area.

A messenger subsequently arrived in Isker. He informed Yermak that Kuchum was preventing a caravan from Bukhara from reaching the town. Believing that the caravan was bringing provisions in addition to merchandize, Yermak set off with 100 soldiers to break the Tatar stranglehold on Isker.

The Cossacks advanced along the Vagai River. When they could not locate the Bukhara caravan along the Vagai River, they traveled up the Irtysh River. As they made their way along the riverbank, Tatar riders conducted harassing attacks. The Cossacks had brought only a small supply of gunpowder and ammunition with them, and it was soon nearly exhausted from the constant skirmishing.

Reaching the upper Irtysh River, Yermak encountered a strongly held fort at Kulary, which had been established to protect the eastern reaches of the Siberian khanate from the Kalmyks. He besieged the fort for five days. When his troops failed to breach the fort’s defenses, Yermak ordered his men to withdraw to Isker.

The failure at Kulary emboldened the Tatars and Karacha. As his Cossack force was retreating, another messenger arrived to inform Yermak that the Bukhara caravan was in fact on the upper Vagai River. The Cossacks rowed to that location from the Irtysh. All the while, a large force of Tatars shadowed them on the riverbank. The Tatars purposely remained out of sight in order to be able to catch the Cossacks by suprise. When the Cossacks failed to locate the caravan, they turned back to the mouth of the Vagai River, where they camped for the night on a river island.

The night of August 5-6, 1585, was dark, and a heavy rain fell. The Tatars crossed a narrow channel undetected and fell upon the Cossack sentries. The main body of Cossacks rallied, and a furious fight unfolded in the darkness. Unable to use their firearms in the rain, the Cossacks fought hand-to-hand as they attempted to cut their way to their boats. As the Tatars attempted to cut the Cossacks off from their boats, the Cossacks desperately fought to reach them. Yermak, who lost 18 men in the fighting, succeeded in securing the boats. As his men scrambled aboard, a Tatar spear pierced Yermak’s throat. Yermak fell mortally wounded into the river and drowned.

Although legend has it that Yermak was wearing a heavy coat of mail presented to him by the tsar, which weighed him down and caused him to drown, this is highly improbable. First, soldiers did not sleep in their armor. Second, Yermak would not have had time to don his mail armor if he was the victim of a surprise attack.

When the Tatars came across Yermak’s body several days later, they stripped it and used it for target practice. His weapons, armor, and clothing were divided among Tatar atamans. After several days, his body was buried in an unmarked grave at an undisclosed location.

With Yermak dead, the Siberian expedition drew to a close. Abandoning Isker, Ataman Mescheryak and Captain Ivan Glukhov led 90 survivors back to Russia. Since the force was too few in number to fight its way back through Pelym, it sailed north along the Irtysh and Ob rivers and crossed the Ural Mountains by a long, roundabout way. A jubilant Kuchum returned to his capital after an absence of almost three years.

Unbeknownst to the survivors, a strong body of Russian fighting men had already crossed the Ural Mountains on their way to Isker. Commander Ivan Mansurov led 700 troops to Isker, where they ran headlong into a large Tatar force. Mansurov saw no sign of the Cossacks.

Not wishing to engage superior numbers, Mansurov bypassed Isker and turned back. He intended to catch up to the Cossacks; however, as his command traveled down the Irtysh, the weather turned cold. Not wanting his men to die of exposure to the elements, Mansurov decided to winter on the Ob River.

Mansurov’s expedition, unlike Bolkhovskii’s, had sufficient winter clothing, provisions, and military supplies. The soldiers used the remaining autumn days to construct a fort near the mouth of the Ob River. The Obskii Fort, and the settlement which eventually grew up around it, later became a major center of Russian power in Siberia.

The Ostyaks made an attempt that winter to destroy the fort but were easily beaten back. The Ostyak atamans soon returned with tribute, pledging loyalty to the Russian Tsar. In spring 1806, Mansurov returned to Russia with the remainder of his command, leaving behind a strong garrison at the fort.

Kuchum did not remain in Isker for long. Shortly after survivors of Yermak’s expedition abandoned Isker, a Tatar civil war flared up in the khanate. Seidyak, son of Bekbulat—murdered by Kuchum—returned from his exile in Bukhara, bringing a powerful force of Kazakh warriors with them. Joining forces with Karacha, Seidyak defeated Kuchum and captured Isker.

Tsar Fyodor sent 300 more men under local ruler Vasilii Sukin beyond the Urals in 1586. A number of Yermak’s former men served as guides in the new expedition. At that point in time, they were not the free Cossacks, but enrolled in the tsar’s service. Sukin established Tyumen on the Tura River, the first Russian city in Siberia.

Another strong Russian detachment of 500 men under Danila Chulkov approached Isker in 1587. They constructed a new fort at Tobolsk using planks from disassembled boats. The location of the fort was 20 miles from Isker at the confluence of Tobol and Irtysh rivers. The Russians inhabiting these settlements collected tribute from the local tribes for the tsar.

The settlements at Tyumen and Tobolsk were the first Russian settlements founded east of the Urals. They were established not only to subjugate the native peoples in the surrounding area, but as a place to collect fur tribute. The Russians deliberately chose the confluences of major rivers and streams, as well as at important portages, for the sites of their new towns.

The princes Seidyak, Karacha, and Uraz-Mahomed, who were the new rulers of Isker, soon approached Chulkov while he was hunting with his falcons. Opening the gates, Chulkov welcomed them. Yermak’s men among Chulkov’s detachment could not forgive Karacha for ambushing Ivan Koltso and his men. During the feast in their guests’ honor, the Cossacks attacked the Tatars and captured all three of the princes. Their guards sold their lives dearly. One of the great warriors killed during the fight was Yermak’s former lieutenant Mescheryak.

Hearing about Seidyak’s capture, the residents of Isker feared Russian revenge, so they abandoned the town. The Cossacks took Prince Seidyak to Moscow, where he swore an oath to the Russian tsar and was enrolled in Russian service.

Even though his health was declining, Kuchum could not accept the loss of his power. The elderly ruler suddenly appeared outside Tobolsk in 1590. Unable to attack the town, Kuchum burned down nearby villages and indiscriminately massacred both Russian and Tatar inhabitants. The Russians, with the assistance of their new Tatar allies, set off in pursuit. They caught up with Kuchum near Lake Chilikul and defeated him, but the wily Kuchum escaped again.

With the Russians still pursuing him, Kuchum retreated to the southeastern corner of his former khanate. The 1,500 troops sent against him included friendly Tatars and Bashkirs. Cherkass Aleksandrov, who was one of Yermak’s former lieutenants, commanded the force.

Advancing up the Irtysh River, the Russians built an outpost that later became the town of Tara. The Russian force drove Kuchum and his last army east towards the upper Ob River. Emissaries of Tsar Boris Gudonov offered Kuchum clemency if he would surrender, but the blind old man, who considered capitulation to be a disgraceful act, refused to capitulate.

The Russians cornered Kuchum and 500 of his warriors near the Irmen River, a tributary of the Ob River, on August 20, 1598. Kuchum put up a strong fight but was soundly defeated. The Russians killed 200 of his warriors and captured 50 more. Among those captured were five of Kuchum’s sons, two grandsons, and five women from his harem. To the Russians’ embarrassment, Kuchum escaped once again to the south. This time, he had no choice but to seek refuge among the Nogai Tatars. Having no use for Kuchum, the Nogais assassinated him in 1600.

The establishment of Tyumen in 1586 opened a new phase in the conquest of Siberia that was driven by the increasing demand in Europe for luxury furs. Rather than haphazard exploits by small parties of trappers and traders, the Russian government embarked on a systematic program of exploration and exploitation. The Cossacks made sure that they always constituted the vanguard of the Russian advance east. Unlike Yermak’s rush to Isker, every new Russian territorial advance was preceded by the establishment of new towns and villages.

Expanding east to the great Amur River in the mid-17th century, Russia became entangled in a military conflict with the Qing Empire, the last Chinese imperial dynasty. After suffering a temporary setback at the hands of Chinese, the Russians in 1639 reached the shores of the Pacific Ocean in 1639.

Tsar Peter the Great, in one of his last acts before he died, ordered Danish navigator Vitus Bering in 1725 to begin exploring the North Pacific for potential colonization. In the wake of explorers such as Bering came waves of settlers. The Russians established the first European settlement in Alaska at Three Saints Bay, near present-day Kodiak, in 1784.

By the mid-1860s, the Russian population of Siberia numbered in the millions. As the Russian population increased, native populations suffered drastic decreases. With them the Russians brought diseases previously unknown in Siberia, such as smallpox. Some native peoples, such as the Tungus and Yakut, lost as much as 80 percent of their population to disease.

Up until 1930s, the process by which Russia acquired Siberia was referred to as a conquest. But political expediency in the 20th century required a less negative connotation, and so the conquest was referred to as an annexation. For this reason, the Soviet Union portrayed it as a voluntary union of the native Siberian populations with the greater Russian population.

Yermak, the Cossack ataman who opened the door to Siberia, obtained the status of a national hero. His expedition had a profound and far-reaching effect on Russian history. By the late 17th century, Russia’s borders were similar to those the country has now.

Great article and very informative, especially given Communist China’s recent expansionist activities …

… but a map would really, really help.