By Mike Phifer

On March 1, 1461, English Chancellor George Neville faced a large crowd of Londoners in St. John’s Field outside the city. Neville asked the people if they believed sitting King Henry VI was fit to rule. “Nay, nay!” they cried. Would they rather have Edward IV, the Duke of York, as their king? “Yea, yea!” they answered. Two days later, the Archbishop of Canterbury, the bishops of Salisbury and Exeter, and other leaders held a council and ruled that Edward should be the king of England. The following day, 18-year-old Edward went to Westminster to accept the crown and scepter as king. There was no formal coronation, however. The Yorkists may have wanted Edward to be king, but the Lancaster forces still supported Henry VI. Blood would have to be shed before it was ultimately determined which man would rule England. The white rose of York and the red rose of Lancaster were set against each other.

Before he had turned a year old, Henry VI had become king of England and France on October 21, 1422. His grandfather, Henry IV, was the first king of the house of Lancaster, while Henry VI’s father, Henry V, had been a strong, ambitious king who captured a good part of France and put it under his reign. Henry VI would prove to be nothing like his forebears. In 1445, the king married French Princess Margaret of Anjou, giving her as a dowry the French province of Maine. With the province back in French hands, English-held Normandy was open to invasion and was lost in 1450. England’s empire in France was quickly crumbling under the weak if not indeed simple-minded king.

Things were not well at home, either. In 1450, open rebellion broke out, putting London briefly into anarchy as reform-minded rebels from Kent entered the city angry at the losses in France and the resulting damage to trade. They were unhappy mainly with the king’s senior counsellors, spelling out in a manifesto: “We believe the king our sovereign lord is betrayed by the insatiable covetousness and malicious purpose of certain false and unsuitable persons who surround his highness, day and night, and daily inform him that good is evil and evil is good.”

It was rumored that Edward IV’s father, Richard Plantagenet, the Duke of York, had been behind the rebellion. York had been lord lieutenant of Normandy and had helped finance the war in France. Blamed for various failures on the Continent—not all of his own making—York had been removed in 1447 and sent to Ireland to get him out of the way. To make matters worse, York was replaced as the king’s chief adviser by his longtime nemesis, Edmund Beaufort, the Duke of Somerset.

For the better part of a decade, York and his allies worked to undermine King Henry VI, sometimes secretly in the halls of government, sometimes openly on the field of battle. Matters came to a head in June 1459, when York and his most powerful supporters, the Dukes of Salisbury and Warwick, marched to the king’s castle at Kenilworth to take him captive. At Ludlow, the combined Yorkist forces began a final move toward Kenilworth. They were not to make it. Spotting the king’s large Lancastrian army between Worcester and Kidderminster, York and his allies decided to retreat to Worcester. From there they fell back to Tewksbury.

Rejecting a general pardon offer, the Yorkists continued their retreat, stopping on October 12 at Ludford Bridge over the River Teme and establishing a defensive position. Heavily outnumbered and suffering from low morale, York and his allies endured a major blow when Warwick’s second-in-command, Andrew Trollope, deserted to the king’s side, taking with him both much-needed troops and York’s battle plans.

That same night, York, Warwick, and Salisbury fled, leaving the army on its own. Queen Margaret was merciful to the abandoned Yorkist troops, who were pardoned after being fined and imprisoned for a short while. York fled to Ireland, while the others fled across the English Channel to Calais, where they found safety with Salisbury’s brother, Lord Fauconberg. Although temporarily defeated, the Yorkists were not done yet. Warwick and his allies began to plot their return.

At Calais, the Yorkists worked to rebuild their power base. The region was commercially crucial to the wool trade, which was England’s main source of wealth. The Lancastrians could ill afford to let the Yorkists occupy Calais. Henry Beaufort, the new Duke of Somerset (his father had died in battle in 1455), was sent to recapture the valuable port. Somerset was repulsed, although his forces managed to secure a castle from which they launched harassing attacks. In early 1460, the Yorkists struck back, raiding Sandwich twice and capturing two Lancastrian fleets preparing to sail on Calais.

On June 26, the Yorkists struck Sandwich again, but this time it was no raid. Landing at Sandwich with a few thousand men, the Yorkist army began to swell with recruits. A few days later they were in London, where they trapped the small Lancastrian force under Lord Scales in the Tower of London. Before leaving to move against the king’s army south of Coventry, the Yorkists reaffirmed their oath not to harm the king, but merely to remove him from his enemies. The king, meanwhile, having left Queen Margaret and their son in Coventry, led his army to Northampton, where they fortified their camp outside town. There the king awaited the Yorkists.

He did not have long to wait. By the evening of July 9, a 7,000-man Yorkist army commanded by Salisbury, Warwick, and York’s son, Edward, the Earl of March, had reached Northampton. Facing them with their backs to the River Nene was the 5,000-man Lancastrian army draw up in a good defensive position behind ramparts strengthened with cannons. The Yorkists began their advance across the boggy ground toward the Lancaster defenses. Rain made the attack more difficult for the Yorkists but also proved beneficial by rendering the enemy cannons useless. The king’s forces were quickly defeated, and the king was captured and taken to London. Upon hearing of the king’s defeat, Scales surrendered the Tower of London.

When York heard of the victory at Northamp- ton, he returned to London from Ireland. Heading straight to Westminster Hall, he literally put his hand on the English throne. A compromise was reached with Parliament in October 1460. Under the so-called Act of Accord, Henry would remain on the throne, but York would govern on his behalf. Upon the king’s death, York and his heirs would assume the crown on their own. Queen Margaret, understandably, had no intention of agreeing to a plan that would rob her son, the Prince of Wales, of his inherited right to be king. She began to build an army in northern England of longtime Lancastrians and newly recruited Scottish and Welsh auxiliaries.

After sending his son Edward to the Welsh border to recruit troops, York and his other son, Edmund, 17, headed north to deal with Margaret. Bad weather made things miserable for York and his men as they marched north deeper into Lancaster territory. At Worksop, in Nottingham, York’s vanguard was cut to pieces by Lancastrian troops led by the turncoat Andrew Trollope, forcing York to withdraw to Sandal Castle, near Wakefield, and wait for reinforcements.

Lancastrian forces in the area continued to grow; they now numbered close to 15,000 men. Cut off from Warwick in London and his son Edward in Wales, York was in a bad situation. It was about to get worse. On December 30, a Yorkist foraging party was attacked by Lancaster troops under Somerset, the Earl of Northumberland, and Lord Clifford. Desperate for food, York charged out from the castle to save the foragers, heading straight into an ambush.

York quickly discovered that the troops attacking his foragers were not the whole Lancaster army. Outnumbered, he and his men fought desperately for about half an hour before they were overwhelmed. York was cornered in a stand of elm trees and hacked to death, while Edmund attempted to escape to Wakefield. Lord Clifford caught up with him on Wakefield Bridge. Ignoring the youth’s pleas from bended knees, Clifford was pitiless. “By God’s blood,” he said, “thy father slew mine, and I will do thee and all thy kin.” Drawing his sword, Clifford plunged the blade through the boy’s throat and out the back of his neck. Salisbury was captured the next day and beheaded. His head, along with the heads of York and Edmund, were put on display over the gates of the city of York. Atop York’s head a paper crown was placed in mockery.

Queen Margaret now moved her army south toward London, burning and pillaging as they went. Many of these plunderers were the Scots, to whom the queen had promised that all the country south of the River Trent was fair game. Refugees escaping from Margaret’s marauding army brought with them horrific stories of the northerners. Warwick played up these atrocity stories as he set about organizing the defense of London.

Meanwhile, on the Welsh borderland, Edward learned of the deaths of his father and brother. On February 2, 1461, he met a Lancaster force under the Earls of Pembroke and Wiltshire at a place where four roads met near the River Lugg at Mortimer’s Cross in Herefordshire. Edward routed the Lancastrians and chased them for 16 miles. Ten lords were captured and quickly executed, including Owen Tudor, grandfather of future King Henry VII.

Back in London, the Earl of Norfolk left the city with a Yorkist force and the captive King Henry VI in tow. Outside of St. Albans, Norfolk joined up with Warwick on February 12. Five days later they were attacked by Queen Margaret’s army of about 12,000 men. Badly surprised, Warwick was defeated and forced to withdraw, leaving behind his royal prisoner, who was reunited with his wife and son.

Yorkist London was spared a sacking from the queen’s army. When news of Edward’s victory at Mortimer’s Cross reached Margaret, she decided to withdraw to the Midlands and the north, both firm Lancaster territory. There she could recruit more troops, while Edward would have the disadvantage of having to fight her on her own ground.

Warwick and his defeated army linked up with Edward, who marched toward London after hearing of the St. Albans defeat. The united Yorkist forces entered London together on February 26. A week later Edward was proclaimed king. Formal coronation would have to wait, however, until the existing king and his queen could be dealt with.

Edward wasted no time in preparing to attack the Lancastrian army. On March 5, the day after his crowning, Edward dispatched Norfolk into East Anglia to recruit more men, while Warwick headed out two days later to recruit in his lands. On March 11, Lord Fauconberg set out with the vanguard of the army, consisting of 10,000 footmen. Edward followed with more troops a day or two later, bringing with him a long baggage train of wagons and carts. In contrast to the Lancastrians, Edward gave strict orders to his army not to rob, rape, or plunder on their march. Those who did would face the death penalty. Thanks to immense loans from merchants in London and Calais, Edward’s soldiers were able to pay good money for everything they needed.

While recruiting around Coventry, Warwick had the grim satisfaction of capturing the Bastard of Exeter who had executed Salisbury, Warwick’s father, after the battle of Wakefield. Warwick was not long in having him killed. Warwick then united with the forces of Fauconberg and Edward on their way to York. The commanders decided to head to Pontefract Castle, where they could refresh themselves and wait for Norfolk. Norfolk, however, was quite sick and there was some concern that he would show up at all. After reaching Pontefract, Edward sent Lord Fitzwalter with a small force to seize and hold the bridge at Ferrybridge that spanned the River Aire. Fitzwalter’s men found the bridge wrecked and quickly set to constructing a temporary platform over it.

The Lancastrian army, meanwhile, was at York, which despite the city’s name was a Lancaster stronghold. Recruiting had gone well for the queen’s army, and although many soldiers came from the north, not all did. Men also joined from the south, east, and west of England, as well as from Scotland and France, making it more than just a war between the north and the south. The Lancastrians had a majority of nobles fighting with them as well.

Leaving the king and queen and their son in York, Somerset led the army to Tadcaster, west of York. From there they marched south crossing the bridge over the River Wharfe, which was damaged in the process, then continued down the Old London Road to ford the flooded River Cock at Towton.

Lord Clifford, whose father had been killed five years earlier at the first Battle of St. Albans, rode south with a force of 500 mounted troops, surprising Fitzwalter’s force at Ferrybridge in the early hours of March 28. Most of the Yorkist troops were wiped out, including Fitzwalter and the Bastard of Salisbury, Warwick’s half-brother. A soldier who escaped the massacre hurried to warn Warwick of what had happened. Warwick immediately mounted his horse and galloped to Edward’s side. Dismounting, Warwick drew his sword and killed his mount, proclaiming dramatically, “Let him fly that will, for surely will tarry with him that will tarry with me.” He would not retreat as he had done at St. Albans.

Edward warned his men that any who wanted to leave should do so now, since those who ran once the battle was joined would be killed, with their slayers receiving double wages for doing so. Edward then collected a group of soldiers and hurried up the road to retake the bridge, while the main Yorkist forces prepared to follow after him.

The fighting at Ferrybridge was fierce, with Clifford and his tough troops desperately holding on to the narrow passageway over the bridge and resisting all Yorkist attempts to take it. In one charge Warwick was struck in the leg with an arrow. Meanwhile, Edward ordered Fauconberg to take part of the army three miles to the west and cross the River Aire at Castleford to strike Clifford’s force in the flank.

When Clifford spotted this threat to his flank, he ordered a summary retreat. After finally being pushed off the bridge, Clifford and his men quickly remounted and thundered up the road toward Towton. Yorkist troops galloped after them and caught them 2½ miles from Towton at a place called Dinting Dale. Clifford’s men were wiped out and Clifford himself, after removing his gorget (rarely worn at the time), was fatally struck in the throat by an arrow.

With Ferrybridge now cleared of Lancaster forces, the main Yorkist army made it way toward Towton. At nightfall Edward decided to make camp. It was an uncomfortably cold and icy night, made doubly so since Edward’s men were short of supplies after leaving their baggage train back at Ferrybridge. Besides the cold night and shivering, hungry troops, Edward was concerned about the whereabouts of Norfolk, who had not yet joined the main army. With a battle looming the next day that very well could decide who ruled England, Edward could only hope that Norfolk had remained loyal.

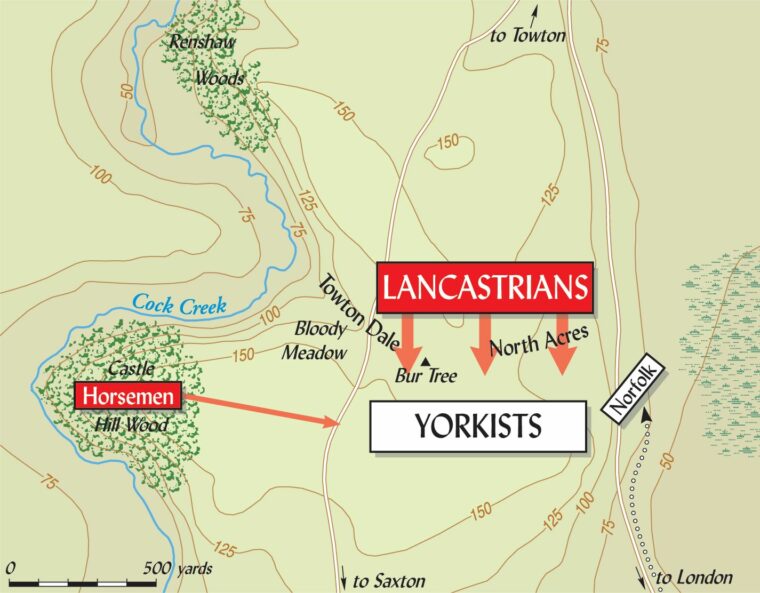

The morning of March 29, Palm Sunday, brought with it a biting wind and a sky threatening snow. The opposing forces began to prepare for the bloodletting to come. The Lancastrian army took up an ideal position on the battleground. The ground between Saxton and Towton was a plateau, higher than the surrounding farmland, but it was by no means flat. The northern part of the plateau was the highest and sloped steeply downward for 400 yards. Taking the high ground, the Lancastrians’ right was protected by a severe drop to a waterway known as Cock Creek, while to their left was treacherous marshland. The Yorkist army would have no choice but to attack uphill.

With their banners flapping in the wind, Edward’s troops began to form for battle. The Yorkist army numbered 20,000 men, while Somerset had 25,000 soldiers. This war, sparked to a great extent by two men—Richard Plantagenet, the Duke of York, and Edmund Beaufort, the Duke of Somerset—was now being fought by their sons, who were leading their respective armies in the decisive battle of the war. It was in many ways a blood feud, with numerous private and personal scores to be settled. Neither army intended to show quarter to the other.

Before the fighting began, both armies took Mass. It was 9 am before Edward’s army assumed its final position. By this time the weather was raw, whipping the soldiers with snow and sleet driven by a strong south wind. As it turned out, the weather would play heavily in the Yorkists’ favor.

Fauconberg with 10,000 archers moved out first toward the Lancastrian archers positioned in front of their army. The Yorkists archers moved forward slowly in a 10-man-deep checkerboard formation that allowed them better visibility and room to maneuver. With a draw weight of between 100 to 200 pounds, an effective range of about 300 yards and a rate of fire of 10 arrows a minute, the English longbow was a fearsome weapon in the hands of archers trained from childhood to use it.

Fauconberg, a veteran of the French war, fully intended to take advantage of the weather. With the wind blowing at his back, he halted his longbowmen and ordered the archers to loose one volley of arrows and then wait. As Fauconberg anticipated, the Lancastrian archers had trouble seeing the Yorkists who were raining down death on them because of the blinding snow being driven into their faces. They replied as best they could, but unable to see their enemies and shooting into the wind, their arrows fell far short of Fauconberg’s men. The Lancastrian longbowmen continued to let fly until their sheaves of 24 arrows were exhausted.

When the Lancaster arrows stopped raining down, Fauconberg ordered his longbowmen forward with orders to “knock, draw and loose” another volley of arrows. When they ran out of their own arrows, the Yorkist archers simply pulled the Lancaster arrows out of the ground and fired them back at their previous owners.

With 10,000 Yorkist longbowmen shooting 10 arrows a minute, an astonishing 100,000 arrows a minute fell into the Lancanstrian position, sowing havoc and death. The Lancastrian army had no choice but to advance. Stepping over and around the wounded and the dead, Somerset’s army pushed forward toward the Yorkists with their banners flapping, shouting, “King Henry! King Henry!” The knights moved forward on foot with the other troops, not wanting to make themselves sitting targets to the deadly longbowmen. As the Lancastrians came on, Fauconberg and his archers fell back to the rear. It was now up to the men-at-arms to continue the battle.

With the archers out of the way, the Yorkist men-at-arms moved forward to meet the oncoming Lancaster army on more level ground at the bottom of the slope. The battle devolved into bloody hand-to-hand combat as the armies collided with a shout. Troops fought as units, keeping close together to protect their lords and prevent the enemy from breaking through. Each side thrust and jabbed at the other with sharp staffs and great swinging blows from their poleaxes. Anyone who lost his footing in the slippery conditions and fell to the ground stood a good chance of being trampled by the mass of men above him.

As the battle raged on, the numerical superiority of the Lancaster forces began to show, pushing the Yorkists back in Edward’s sector. The Yorkist left flank began to buckle but did not break. At this point, some 200 Lancastrian lancers came charging out of Castle Hill Wood and struck the enemy left. Although the attack caused some confusion and localized panic, the line held firm. Edward himself was in the thick of the fighting.

While snow continued to blanket the battlefield, the Yorkist left was being pushed back to the slopes. Somerset was on the verge of winning a great victory if his troops, with their numerical superiority, could only push a little harder. Then the much anticipated Norfolk finally arrived, hurrying his men up the road from Ferrybridge. The fresh troops, both mounted and on foot, arrived on the right side of the plateau in early afternoon and scrambled up the snow-covered slope, extending the Yorkists’ right flank and falling in on the enemy’s left.

The sight of fresh troops was demoralizing, but the Lancastrians pressed on. Intense, bloody fighting continued in the fields between North Acres and Towton Dale. The Lancastrian left was feeling the pressure of the Yorkist reinforcements, and panic seized some of the battle-weary soldiers, causing them to break. The panic spread like wildfire. Somerset and other nobles, realizing what was happening, mounted up and tried to escape, but the bloodletting was far from over.

Somerset’s choice of a defensive position ironically caused the deaths of many his men, who were caught in a trap with no open escape route. Many attempted to flee across Bloody Meadow, which lay behind them, but they were quickly run down and killed by the pursuing Yorkists. Others managed to reach Cock Creek and desperately tried to find a way across it. Some drowned trying to wade across, realizing too late that the creek was deeper than it looked. The exultant Yorkists chased after their beaten foes, killing them wherever they found them. This was made easier because many Lancastrians pulled off their helmets and threw away their weapons to allow them to run faster. The routed Lancastrians were hounded for 10 miles, all the way to the gates of York.

Disagreement remains over how many men died at Towton. Some chroniclers put the body count as high as 38,000, while modern historians put the number at 8,000 killed for the Lancastrians and 5,000 for the Yorkists. Whatever the number, it was undeniably a bloody day, especially among the nobles who died on the battlefield. The latter included Andrew Trollope, who had defected from the Yorkists at a crucial moment two years previously. Forty-two Lancastrian knights were executed after the battle.

When news of the defeat reached King Henry VI and his wife, they and their son fled northward along with Somerset, making their way to safety in Scotland. Edward returned in triumph to London and assumed the crown as Edward IV. The great victory at Towton had broken the back of organized Lancastrian resistance, but matters in England were far from settled. For the next nine years, Margaret regularly crisscrossed the English Channel, seeking aid from French King Louis XI to continue the struggle. In the meantime, the feckless Henry VI managed to get himself recaptured and imprisoned in the Tower of London.

In 1470, Margaret formed an unlikely alliance with Warwick, who had fallen out with King Edward IV and offered his sword to the deposed queen. To cement the agreement, Margaret’s son, Edward, Prince of Wales, married Warwick’s daughter, Anne Neville. Faced with the threat of a new Lancastrian force, Edward IV abandoned London and fled to safe haven in Burgundy. Warwick arrived in the capital and restored Henry briefly to the throne.

Recovering his nerve—if he ever lost it—Edward IV returned to Yorkshire and recruited another army, defeating and killing Warwick at the Battle of Barnet on April 14, 1471. Three weeks later, on May 4, the Yorkists defeated Margaret and her remaining allies at the Battle of Tewksbury. The Prince of Wales died in the fighting. His father, Henry VI, came to a mysterious end on May 21, when he was found dead in the Tower of London after a visit from Edward’s brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester (the future King Richard III). Margaret would eventually return to France and die in exiled poverty. The English crown now sat firmly atop the white rose of York.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments