By Michael D. Hull

A few days after German panzers rumbled through the chill, foggy Ardennes Forest early on December 16, 1944, breaching thinly held American lines and causing widespread confusion and near panic, a number of Allied units were rushed in to plug the gaps.

One was Maj. Gen. Alexander R. Bolling’s 84th Infantry (“Railsplitter”) Division, which deployed to Marche, Belgium, where it hastily set up a perimeter defense line on December 21-22.

After several German assaults pierced its lines, the division slogged through snow and sleet to repel further attacks and recapture the town of Verdenne on Christmas Day.

Early in January 1945, the 84th became part of an offensive aimed at reducing the enemy bulge in the Ardennes, and followed the 2nd Armored (“Hell on Wheels”) Division to retake the strategic Belgian town of Houffalize.

The Railsplitters, who had landed at Omaha Beach in November 1944, fought with British Army support to reduce the Geilenkirchen salient north of the German city of Aachen and captured the towns of Wurm and Muellendorf. The soldiers saw plenty of action during their “walk through hell” in the Battle of the Bulge and during their later crossings of the Roer and Rhine Rivers. The cost was high. The division lost 1,284 men killed outright, 5,098 wounded, and 154 who died of their wounds.

One of the lucky survivors was a wiry, good-natured former student and jazz drummer from Shrewsbury, Mass., named Roscoe C. “Rockie” Blunt, Jr. Like his comrades, the 19-year-old expert rifleman and demolitions specialist quickly became a man in the snow, fog, and ice of Belgium and Germany during the bitter winter of 1944-1945.

He survived a lone encounter with a German King Tiger tank at Grand Menil in Belgium and won the coveted Combat Infantrymans Badge, the Bronze Star, and the Purple Heart. But he never regarded himself as any kind of hero. Regardless, the astute young man knew that he was helping to make history so, contrary to Army regulations, he kept a diary in his pack. When time and conditions allowed, he sat down on his helmet and scribbled his observations of combat.

He survived a lone encounter with a German King Tiger tank at Grand Menil in Belgium and won the coveted Combat Infantrymans Badge, the Bronze Star, and the Purple Heart. But he never regarded himself as any kind of hero. Regardless, the astute young man knew that he was helping to make history so, contrary to Army regulations, he kept a diary in his pack. When time and conditions allowed, he sat down on his helmet and scribbled his observations of combat.

Long after the war and his subsequent 32-year stint as an award-winning police reporter for the Worcester (Mass.) Evening Gazette, Blunt turned his fading, dog-eared journal into Foot Soldier (Da Capo Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2002, 296 pp., 33 photographs, maps, $16 softcover). Tightly written and brutally honest, it is an intelligent, vivid, and poignant record of men under fire. Blunt’s combination of firsthand experience and reporter’s skill makes this book a sure winner. Unlike many such foxhole memoirs, this one is literate and sure to become a classic.

Not a day goes by, says the author, that his thoughts do not return to those gut-wrenching months of 1944-1945. The snap of an ice-coated branch in a winter storm reminds him of incoming fire; the passing rumble of a diesel truck recalls the low, throaty, chugging sound of a German V-1 rocket; and burning autumn leaves evoke the pungent smell of burning flesh. His narrative pulls no punches.

Blunt writes of finding a young Belgian mother and child left on a roadside after being disemboweled by retreating German troops; of being pelted with rotten apples by French farmers in retaliation for the damage caused to their land by Allied bombers; of the periodic exhilaration of combat (a “thrilling sport”); of the night when he almost died of exposure in a foxhole, waking to find his feet encased in six inches of ice; of the casual shooting of German prisoners by GIs; of the perpetual foraging for alcohol and souvenirs; of the horror and outrage felt when liberating concentration camps; of the widespread carnage in vanquished Germany; and of the fate of a captured Waffen-SS soldier who had given false information that caused the deaths of an American squad. Blunt watched the brutal beating and summary execution of the German.

This book may well be the most eloquent and powerful memoir to emerge from the Battle of the Bulge.

Recent and Recommended

Recent and Recommended

Finest Hour: The Battle of Britain by Tim Clayton and Phil Craig, Touchstone Books, New York, 2002, 349 pp., 37 photographs, notes, index, $14 softcover.

Late one sunny August afternoon in 1940, during the height of the Battle of Britain, 27-year-old reporter Whitelaw Reid of the New York Herald-Tribune came upon a family relaxing in their garden near Dover.

As British and German vapor trails skeined the blue sky overhead, the parents nonchalantly read novels while their children scampered around playing cowboys and Indians. Suddenly, there was the shriek of power dives and the crackle of gunfire bursts. The books were cast aside and the family took to its heels—but not for cover.

Snatching up pairs of field glasses, they ran to a nearby hill to watch the action from a better vantage point. After German bombs had fallen indiscriminately around the Kentish countryside, an old villager leaned over his fence and told reporter Reid indignantly, “It’s all wrong, this is—the way the Germans are bombing the little churches and the little pubs.”

When the American looked suitably shocked, the old man smiled, “It’s all right; they didn’t get the pub.” Reid later typed out his story for the Herald-Tribune: “Nazi raids fail to upset British …”

It was the golden summer of 1940—a tense, heady time of carefree, tousle-haired young Hurricane and Spitfire pilots scrambling at a few minutes’ notice to take off and challenge ominous black specks in the sky that were approaching German Dornier and Heinkel bombers. It was a time of London firemen and provincial air-raid wardens in tin helmets, of road signs and railway-station names blacked out to foil would-be invaders. Makeshift Home Guard roadblocks stood at country junctions, and antiaircraft gun emplacements were dug into golf courses. Children rushed from classrooms into shelters, and sandbags were piled high, plate-glass windows were taped, and gas masks were within an arm’s reach.

It was a summer of destiny, and the greatest turning point of World War II, when the fate of the free world hung in the balance and was rescued by a few hundred pilots of Royal Air Force Fighter Command. “Never was so much owed by so many to so few,” as Prime Minister Winston Churchill told an overcrowded House of Commons on the sultry afternoon of August 20.

It was Great Britain’s darkest hour, and also her finest, as Tim Clayton and Phil Craig remind us in their human, graphic, and vivid book, a companion to the PBS television series. This is a compelling narrative.

The authors have woven the reminiscences of airmen, soldiers, seamen, housewives, politicians, diplomats, and journalists into a gripping and enlightening review of the fateful year 1940. It is a work of immediacy and high drama.

The climactic Battle of Britain is the centerpiece, but the year is chronicled day by day in the context of its events, from the end of the “Phony War” and the British Expeditionary Force’s deliverance from Dunkirk in May-June to the heroic sacrifice of the merchantman Jervis Bay to save an Atlantic convoy that November. The tensions and uncertainties of 1940 and the greatest aerial campaign in history have been well documented before, but this book takes a fresh approach that makes it rewarding and highly readable.

Clayton is a former Oxford research fellow, and Craig is a television documentary producer.

Crumbling Empire by Samuel W. Mitcham, Jr., Praeger Publishers, Westport, Conn., 2002, 297 pp., 37 photographs, maps, tables, appendices, index, $27.50 hardcover.

Crumbling Empire by Samuel W. Mitcham, Jr., Praeger Publishers, Westport, Conn., 2002, 297 pp., 37 photographs, maps, tables, appendices, index, $27.50 hardcover.

When Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus’s Sixth Army was surrounded and decimated at Stalingrad in 1942-1943, it was considered a major turning point of World War II and the greatest disaster suffered by the Germans in the East.

It was indeed a turning point for the Allies, says Samuel Mitcham, but the loss of 230,000 men there, sacrificed because of Adolf Hitler’s order to stand, fight, and die, was actually the third-ranking catastrophe to befall the German armies on the bitter, unrelenting Eastern Front. More than 300,000 men of Field Marshal Ernst Busch’s Army Group Center were lost in the Battles of Vitebsk-Minsk in June-July 1944, and another 270,000 were lost in the Romanian campaign that August and September when Colonel General Johannes Friessner’s Army Group South Ukraine was annihilated.

In the summer of 1944, Soviet Marshal Josef Stalin hurled into battle more than six million men, 9,000 tanks, 16,000 fighters and bombers, and more than 12,800 field guns and rocket launchers.

More German troops were lost in Romania in 10 days than in the entire Normandy campaign of 1944, the author points out, and their losses in Hungary were greater than in the Ardennes counteroffensive in the winter of 1944.

Even after the Stalingrad disaster, Mitcham explains in his solid and detailed history of the German defeat in the East, the Wehrmacht was still strong and reacted with the swiftness and resilience that characterized it on all fronts, from North Africa to Normandy. Within two months of Stalingrad, the able Field Marshal Erich von Manstein launched a brilliant offensive that smashed several Soviet armies and recaptured Kharkov, the fourth largest Russian city. Three months later came Kursk, the greatest tank battle in history.

The point of all this, Mitcham writes, is that German defeat was not a foregone conclusion in the spring of 1943. However, by 1944, Hitler’s “stand fast” orders had clamped a paralysis on his high command and the field generals. Outnumbered three to one in men, five to one in armor, and 20 to one in aircraft, the German armies were slaughtered as casualties mounted.

When Budapest fell in February 1945, to vodka-swilling, pillaging, and raping Red Army troops, Hitler’s eastern empire virtually ceased to exist. The war was now in its sixth year, and the Third Reich’s legions had finally been thrown back to roughly where they had started their march of conquest in 1939. The next battles against the onrushing Red Army would be waged inside the fatherland, and Nazi Germany was entering its death throes.

This book, by the author of 15 other outstanding works on Rommel, the Luftwaffe, and other aspects of Nazi Germany, examines the decline of the Third Reich with crystal clarity and perceptive analysis. It is impressively documented and authentic.

The House of Krupp by Peter Batty, Cooper Square Press, New York, 2001, 344 pp., 9 photographs, index, $18.95 hardcover.

The House of Krupp by Peter Batty, Cooper Square Press, New York, 2001, 344 pp., 9 photographs, index, $18.95 hardcover.

After the flares of Royal Air Force Bomber Command Mosquito pathfinders had pierced the smoky haze above the sleeping German city of Essen on the night of March 5, 1943, came 443 Lancaster, Halifax, and Wellington bombers to unleash a rain of death and destruction.

Their bombs laid waste to 160 acres in the center of the iron and steel complex in Germany’s industrial heartland, the Ruhr Valley, and another 450 acres were badly damaged. It was a night of horror that the citizens of Essen would long remember.

Their city was the target for many more punishing visits by Bomber Command, for it was the home of the great Krupp armament factories, major supplier to the Nazi war machine. These were the plants that had forged cannon for Chancellor Otto von Bismarck in his wars against Austria and France almost a century earlier, that had built the notorious “Big Bertha” gun with which Kaiser Wilhelm II had smashed Belgian forts in 1914, and that were now tooling tanks and guns for Adolf Hitler.

Before World War II was won, RAF bombers would make almost 200 full-scale raids on Essen and drop more than 36,000 tons of bombs on the three square miles of Krupp factories. When British and American troops captured the city in April 1945, they found almost total destruction, “a place of the dead,” as one GI wrote home.

To Germans, says Peter Batty in this definitive history of the industrial dynasty, Krupp has long been the symbol of their nation’s prowess. They like to say, “As the Fatherland goes, Krupp goes”—a sort of Teutonic version of “What’s good for America is good for General Motors.”

Outside Germany, the name of Krupp has been closely identified with that country’s aggression and beastliness in two world wars.

To Frenchmen, says the author, it was Krupp guns that ravaged their country thrice in a century. To Britons, it was Krupp-built submarines that brought them to within three weeks of starvation in World War I and almost repeated the process in 1941-1942. To Russians, it was the giant Krupp railway gun “Fat Gustav” that besieged Sevastopol in 1942 and devastated many cities. To Americans, it was Krupp-built Tiger and Panther tanks that clanked through the Ardennes Forest in December 1944 and caught them napping.

There have been striking parallels between the triumphs and disasters of Germany under Bismarck, the Kaiser, and Hitler, and the rise and fall of the fortunes of the House of Krupp, the author points out. The Krupps themselves have been unscrupulous and grasping masters, but also thoroughly able. Theirs is an ugly, sordid, and immoral story, Batty writes, yet it nevertheless has an epic quality. It is a saga of intrigue and greed, of lust for power and possession of power and, above all, a story of dangerous men.

The author relates it expertly with solid scholarship and narrative excellence.

0 Allies at War by Simon Berthon, Carroll & Graf, New York, 2001, 354 pp., 11 photographs, notes, index, $26 hardcover.

Allies at War by Simon Berthon, Carroll & Graf, New York, 2001, 354 pp., 11 photographs, notes, index, $26 hardcover.

It was May 21, 1943, the 10th day of the Trident Conference in Washington, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and their staffs wrestled with crucial decisions on the course of World War II.

They had agreed to invade Sicily as a follow-up to the defeat of the Axis forces in North Africa. Soviet Marshal Josef Stalin was pressuring for an Anglo-American assault on continental Europe. The U.S. Chiefs of Staff were pushing for an increase in the speed of the massive buildup of men and equipment in Britain, and American scientists were opposing the sharing of atomic bomb data with the British (who had pioneered nuclear research).

Yet, in the midst of these top-level talks that would affect both the war and the future of mankind, one persistent irritant was gnawing at the American president’s vitals. Every day, he dropped a damning document about it on Churchill’s desk. The irritant was General Charles de Gaulle, leader of the Free French Forces based in England. The towering, imperious armored-warfare advocate who had distinguished himself in the 1940 Battle of France, had become a global symbol of French Resistance.

But FDR found him “well nigh intolerable,” while Churchill had come to regard his anglophobic former protégé as a “marplot and mischief maker.” In the public eye, Churchill, Roosevelt, and DeGaulle stood shoulder to shoulder in defense of freedom, says Simon Berthon, but in private their relations were tarnished by contention, distrust, and duplicity.

The basis for a television series he produced for BBC-PBS, Berthon’s book is a dramatic study of this stormy wartime triumvirate. Well crafted and probing, it is a rewarding addition to the annals of World War II.

There was glory at the end for the three wartime allies, Berthon writes, even though FDR did not live to see final victory. Sadly, harmony among them had not been a part of it.

I Was With Patton by D.A. Lande, MBI Publishing Co., St. Paul, Minn., 2002, 286 pp., 30 photographs, index, $24.95 hardcover.

I Was With Patton by D.A. Lande, MBI Publishing Co., St. Paul, Minn., 2002, 286 pp., 30 photographs, index, $24.95 hardcover.

When Afrika Korps panzers rolled through the Kasserine Pass in Tunisia in February 1943 and routed the inexperienced U.S. II Corps, the situation was shored up by British Guards and armored units.

It was the first of several bitter lessons during World War II for the U.S. Army, then well equipped but poorly trained and lacking in fortitude. But the Americans learned quickly in the desert, as was observed by Field Marshal Erwin Rommel.

The II Corps—and American spirit in general—shaped up rapidly in the face of a formidable foe, thanks to a tall, creatively profane professional soldier with a high-pitched voice named George Smith Patton, Jr., who took command with a firm hand. After Maj. Gen. Terry Allen’s 1st Infantry Division “captured” the village of Gafsa, whose Italian garrison had pulled out, the Americans regained much of their lost confidence at the Battle of El Guettar. There, thanks to Patton’s decisive leadership, two German divisions were forced to retreat, leaving behind 30 burning panzers. American mettle shone forth.

Today, nine out of 10 American Army veterans of World War II are likely to tell you that they “served under Patton,” whether they actually did or not. This is more a matter of soldierly pride than falsification. Whether they loved or hated “Old Blood and Guts” during the momentous, defining experience of their lives in 1942-1945, veterans want to be associated with the hard-charging, no-nonsense cavalryman. Patton, many believe, showed, in the face of considerable doubt on the part of both their allies and enemies, that Americans could fight. He emerged from the war as a military legend and 20th-century folk hero.

As the most colorful, most outspoken, and most recognizable U.S. combat leader of the war, it is probably natural that today’s diminishing cadre of former GIs clings to the heroic aura Patton bequeathed.

All this is made abundantly clear in D.A. Lande’s book, a fully researched and crisply narrated collection of reminiscences by men who served under Patton—lieutenants, sergeants, privates—from Bizerte to Gela, from Palermo to St.-Lo, from Nancy to the Ardennes, and from Metz to Pilsen. Candid, humorous, and inspiring, the stories reveal many facets of Patton’s martial charisma.

While he proved himself to be a bold dealer of armored death and destruction in the harsh crucible of World War II, “Georgie” Patton was also a romantic cavalier in the 19th-century mold who believed that combat brought out the best in men. It was all an adventure to him, and he relished war, unlike most of his contemporaries. He was larger than life, and his soldiers knew it.

These memoir fragments reinforce the image that endures today of a seemingly fearless soldier’s soldier who led from the front and was hated by many but respected by all. Veterans of II Corps and the freewheeling Third Army will treasure this book.

George Davis of the 8th Infantry Division, who won the Silver Star in Brittany and saw Patton for the first time in St.-Lo, Normandy, during the critical summer of 1944, recalled, “He was in his command car, a Dodge car with the top off, standing on the front seat and holding on to the windshield. His two pistols on his hips. He stood so straight—the picture of the perfect soldier. It was inspiring to us. We thought, here’s a leader—up here with us, and he’s not afraid. If he can do it, I can do it. It was something you kept with you forever after that.”

There is much affection, pride, and simple eloquence in this collection.

Warlord: Tojo Against the World by Edwin P. Hoyt, Cooper Square Press, New York, 2001, 256 pp., 10 photographs, appendices, notes, index, $17.95 softcover.

Warlord: Tojo Against the World by Edwin P. Hoyt, Cooper Square Press, New York, 2001, 256 pp., 10 photographs, appendices, notes, index, $17.95 softcover.

Bespectacled, buck-toothed, scrawny, and owlish, he appeared to be mild-mannered and malleable, but underneath was a fierce nature.

After all, Hideki Tojo had come to prominence in the Imperial Japanese Army through the Kempetai, the dreaded secret police that brought the Kwantung Army under control and routinely tortured anyone it arrested.

Second only to Adolf Hitler as a hated symbol of Axis villainy during World War II, Tojo was the Japanese dictator with three hats—prime minister, war minister, and army chief of staff—who initiated the Pacific War and directed it until 1944. Going to war was the first of his several major blunders, for, unlike the moderate and more intelligent Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Commander-in-Chief of the Imperial Japanese Combined Fleet, Tojo failed to perceive that the potential industrial and military might of the United States that meant eventual defeat for Japan was inevitable. He was convinced that the Japanese were a superior and invincible race.

The life, career, and fall of Japan’s leading warlord of World War II unfolds at a brisk pace in Edwin Hoyt’s succinct yet detailed biography. He has been a longtime resident of Japan and is one of the most prolific and engaging historians writing today. This revealing book is highly relevant to any study of the 1939-1945 global holocaust because it opens a clear window on what led Japan to war and Tojo’s role in it.

Against the background of the factional clashes, vicious infighting, and periodic assassinations that characterized Japanese politics preceding the war, Tojo is portrayed here as a master manipulator who nevertheless let himself be misled by junior officers, a ruthless plotter, and a loyal disciple of Emperor Hirohito, whom he almost betrayed in the end.

Tojo’s position weakened as events in the Pacific turned against Japan, and he resigned on July 18, 1944, shortly after strategic Saipan fell to U.S. Marine Corps and Army units. He attempted to shoot himself in the chest with a pistol after his nation’s surrender on September 2, 1945, but survived to be one of seven Japanese war criminals hanged by the Allies on December 22, 1948.

Unlike the others, writes Hoyt, the warlord filed no appeal. He had lost the war, and the son of a samurai was happy to die at the hands of his enemies.

Tojo died like a warrior, the author points out, but he was an unsavory character. He had schemed his way into power and, although hard working, authoritarian, and eloquent, he was misguided and shortsighted. Tojo was a soldier first and foremost, and lacked the skills and charisma of a statesman.

During his tenure, says the author, he charged from one blunder to another, many of them self-serving, although he claimed to have no ambition other than to serve his Emperor and nation. He wasted many of Japan’s slender resources in trying to capture Indian territory from the British so that he could establish Subhas Chandra’s pro-Japanese Indian National government.

Tojo’s nickname was “Kamisori” (Razor), Hoyt says, but this had less to do with his intellect than his brutal service in the Kempetai. He was naïve and narrow in outlook, and many regarded him as stupid.

This is an intriguing and smoothly written study by the author of many books about World War II.

Fight for the Sea by John Frayn Turner, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md., 2002, 246 pp., 45 photographs, $34.95 hardcover.

Fight for the Sea by John Frayn Turner, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md., 2002, 246 pp., 45 photographs, $34.95 hardcover.

By July 24, 1945, the U.S. Third Fleet and Royal Navy Task Force 37 were in virtual command of the waters around Japan, pulverizing Tokyo’s airfields and the remains of the Imperial Combined Fleet in Kure Harbor.

In two days, the Third Fleet sank or damaged a quarter-million tons of Japanese shipping and downed 130 aircraft.

Flying from the aircraft carrier USS Belleau Wood, Ensign Herb Law was seriously injured in the left leg while strafing a Japanese airfield, and his plane started smoking. Too low to bail out, he managed to crash-land and flee from the plane. As he tried to bandage his bleeding leg, a woman ran from some nearby bushes and shot at him from 10 yards. She missed and ran for help. The enemy soon found Law.

They stripped him, bound him, and gave him no food or water for three days. He was beaten with clubs, fists, and leather straps, and generally used as a human guinea pig. Yet, he survived to tell about it.

Law’s is one of many naval adventures from World War II chronicled in this richly varied compilation by John Frayn Turner, a Royal Navy veteran and the author of a companion book on fighter and bomber pilots. Humming with action and immediacy, this is a riveting work.

Spanning the entire 1939-1945 war, the stories include the sinking of the proud old battleship HMS Royal Oak by a daring U-boat skipper at Scapa Flow in October 1939, the bizarre end of the German battleship Graf Spee off Montevideo in December 1939, the Pearl Harbor attack, the Battles of Coral Sea, Midway, and Guadalcanal, and more.

Tightly written and authentic, this narrative captures graphically the wide range of actions and hazards endured by British and American seamen.

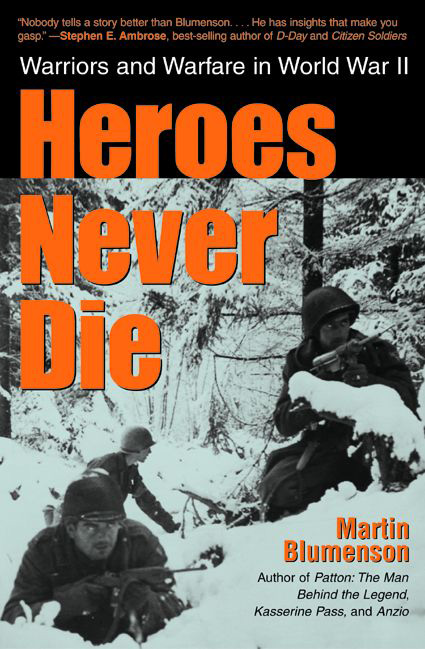

Heroes Never Die by Martin Blumenson, Cooper Square Press, New York, 2001, 644 pp., index, $32 hardcover.

Heroes Never Die by Martin Blumenson, Cooper Square Press, New York, 2001, 644 pp., index, $32 hardcover.

While leading some of his U.S. Rangers one dark night in Italy during World War II, Lt. Col. William O. Darby suddenly halted them, told them to stay silent, and went ahead to investigate a suspicious object.

He soon returned laughing. What he had thought was a German tank was only a haystack. Any other officer would probably have sent someone else forward, but not Darby.

The slender, handsome West Pointer from Arkansas frequently and casually exposed himself to the enemy because, as one of his officers believed, Darby was “deathly afraid that his troops would show fear” and thus encourage their foes. His leadership was personal, and, as one of his soldiers asked, “How can you keep from loving a man like that?” After being killed by a dime-sized fragment from a German 88mm shell on April 30, 1945, Darby was posthumously promoted to brigadier general. He was only 34 years old at the time of his death.

Bill Darby is one of many outstanding World War II leaders, both Allied and German, analyzed in this collection of articles written between 1957 and the present by Martin Blumenson, the distinguished biographer of General George S. Patton, Jr., and author of a host of first-rate military histories. He is a solid researcher, dependable analyst, and smooth writer, and this compendium of lore about leaders, strategies, tactics, and battles is a treasure trove for WWII buffs and scholars. It is packed with fascinating insight into leadership and courage, from Kasserine Pass to Gela, from Salerno to Normandy, and from Paris to Bastogne.

The author examines the qualities and flaws of the top leaders: Churchill, Roosevelt, Marshall, Alanbrooke, Eisenhower, Alexander, Bradley, Montgomery, MacArthur, Nimitz, Hitler, Mussolini, Arnold, von Rundstedt, Rommel, and Patton—and also those outstanding warriors further down the rung, such as Auchinleck, Clark, Slim, Kesselring, Kluge, Ridgway, Collins, Hodges, Truscott, Stilwell, Gavin, Taylor, Middleton, Harmon, Gerow, Eddy, Huebner, Allen, McLain, and Haislip.

Predictably, Patton predominates in this book as Blumenson discusses his character and education, his race against Montgomery to Messina, the notorious slapping incident, his relations with Bradley and the press, his frustrations when the war ended, and his inglorious nonbattlefield death.

One may not agree with all of the author’s judgments, but his wisdom and thoroughness are indisputable. This book is a gem.

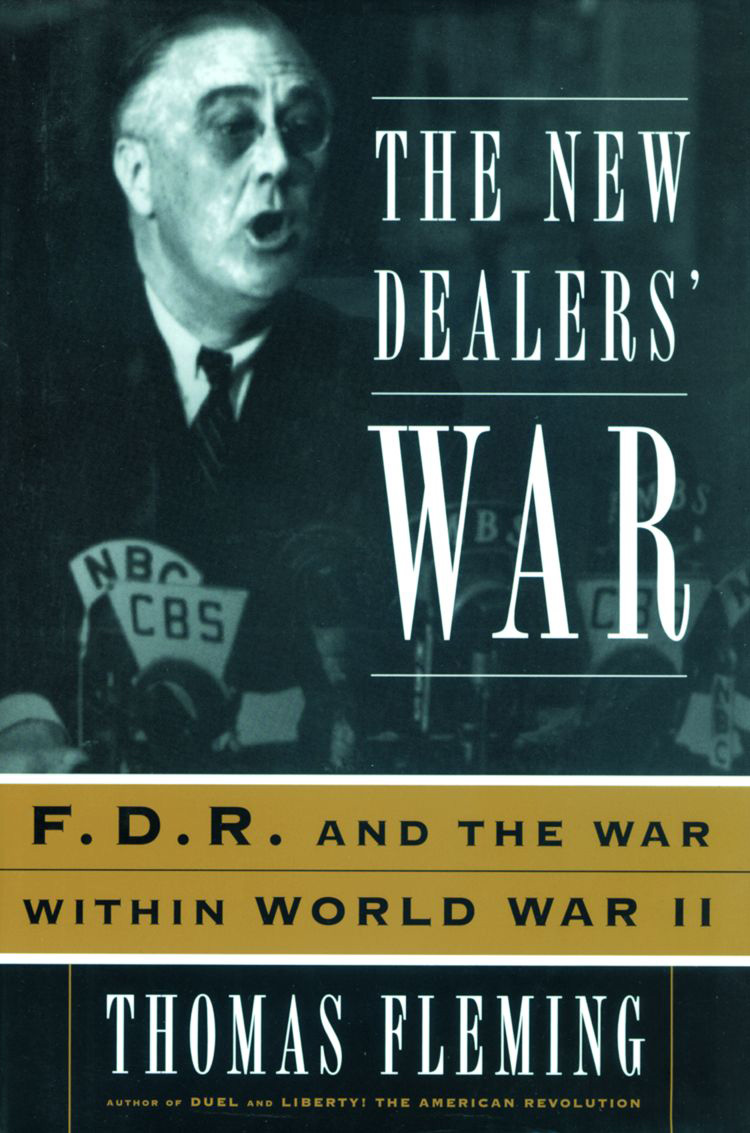

The New Dealers’ War: FDR and the War Within World War II by Thomas Fleming, Basic Books, New York, 2001, 628 pp., 27 photographs, notes, index, $35 hardcover.

The New Dealers’ War: FDR and the War Within World War II by Thomas Fleming, Basic Books, New York, 2001, 628 pp., 27 photographs, notes, index, $35 hardcover.

For 10 days in January 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and their Combined Chiefs of Staff gathered to discuss strategy at the sun-kissed resort of Anfa, three miles south of Casablanca, Morocco.

After offensives in the Atlantic, Pacific, Southeast Asia, Mediterranean, and the skies over Germany had been agreed upon and policy differences smoothed out, Allied war correspondents sat on the grass at Roosevelt’s villa on the last day of the historic conference to hear Churchill and the president sum up the results. The beaming FDR declared that the two Allies had reached “complete agreement” on the conduct of the war, and then dropped a bombshell.

He declared, “The elimination of German, Japanese, and Italian war power means the unconditional surrender of Germany, Italy, and Japan.” Churchill was dumbfounded by the pronouncement and dismayed by its probable impact on the outcome of the war, but quickly endorsed his friend and ally.

One of the most dramatic, high-level moments of the war, and one of its great blunders, in the eyes of many soldiers, politicians, and historians, is highlighted in Thomas Fleming’s stimulating and argumentative analysis of Roosevelt’s policies preceding and during the war. A work of solid scholarship and bristling narrative, this is bound to be a controversial book.

The author says that FDR made it clear after Casablanca that his comment was little more than an afterthought, but suggests that it undoubtedly prolonged the conflict, as the astute Churchill feared. General Dwight D. Eisenhower was appalled by it, and General Albert Coady Wedemeyer said it would “weld all the Germans together.”

Fleming sheds interesting light on Roosevelt’s health as a factor in his rigid commitment to unconditional surrender, in spite of the pleas of many top military and political aides. One of Churchill’s advisers blamed FDR’s illnesses, heart disease, clinical depression, and high blood pressure for the “costly enfeeblement” of Allied unity in the closing months of the war.

This is a thoughtful and challenging book that merits serious study.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments