By John Wukovits

By mid-June 1898, a potent American military conglomeration had assembled off the extreme southeastern coast of Cuba. Thirty-two troop transports brought 819 officers and 15,058 enlisted men to Cuba from Florida, along with 89 newspaper correspondents, 11 foreign military observers, and 10 million pounds of rations. Most of the young American soldiers eagerly sought battle with the Spanish, boasting that the war would end swiftly. One group of officers raised their whiskey glasses and toasted, “To the officers—May they get killed, wounded, or promoted!”

On the other side of the lines, the Spanish forces seemed equally confident. The battle-tested troops waited in well-fortified trenches and guardhouses shielded by barbed wire. A newspaper in Spain informed its readers, with more than a touch of exaggeration, “The average height among the Americans is five feet two inches. This is due to their living almost entirely upon vegetables as they ship all their beef out of the country, so eager are they to make money. There is no doubt that one full-grown Spaniard can defeat any three men in America.” They would soon get the chance to try.

The root causes of the Spanish-American War lay with imperialism. The United States desired overseas colonies, which many European nations had possessed for years in Africa and Asia. “A new consciousness seems to have come upon us,” editorialized the Washington Post in 1898, “the consciousness of strength—and with it a new appetite, the yearning to show our strength, ambition, interest, land hunger, pride, the mere joy of fighting, whatever it may be, we are animated by a new sensation. The taste of Empire is in the mouth of the people even as the taste of blood in the jungle. It means an Imperial policy, the republic, renascent, taking her place with the armed nations.”

Cuba, where Spain’s dying empire retained a fragile hold over the island’s population and resources, offered a golden opportunity. From a mixture of wishing to help free the Cubans from Spanish oppression and desiring new lands, President William McKinley warned Spain that she must grant independence to Cuba or face international sanctions. American newspapers, especially William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal, printed inflammatory and misleading articles depicting the Spanish as cruel overseers who were wantonly killing people and ravaging the country. When the American battleship USS Maine, sent to Cuban waters to monitor the situation, exploded in Havana harbor on February 15, 1898, killing 260 American sailors, sentiment soared for a war with Spain.

“No national life is worth having if the nation is not willing, when the need shall arise, to stake everything on the supreme arbitrament of war,” wrote Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt, “and to pour out its blood, its treasures, its tears like water rather than to submit to the loss of honor and renown.” Fueled by such emotions, on April 25 Congress declared war on Spain.

Convinced that the United States would handily defeat a weary European nation desperately clinging to the last vestiges of its once-proud empire, war fever spread across the land. Famed western scout Buffalo Bill Cody boasted that 30,000 Indian fighters would force Spain out of Cuba in eight weeks. Frank James, brother of the notorious bank robber and murderer Jesse James, offered to command a company of marksmen raised in the West. Hearst’s Journal stated that a regiment of American athletes would frighten the Spanish simply by showing up for battle.

In early June, Maj. Gen. William R. Shafter, an immense man weighing close to 300 pounds, received orders from Secretary of War Russell A. Alger to proceed to Santiago, on Cuba’s southeastern coast, and capture or destroy the enemy garrison there. Among the soldiers under Shafter’s command was Theodore Roosevelt. The well-born New Yorker had left his government post to assemble a regiment of volunteer troops drawn from a fascinating array of figures. The 1st Volunteer Cavalry, popularly known as the Rough Riders, painted a microcosm of the aggressive young nation. It carried on its roster New York City police officers, Ivy League quarterbacks, Native Americans, cowboys, sheriffs and outlaws, clergy and scoundrels.

“It is as typical an American regiment as ever marched or fought,” wrote Roosevelt to a friend, “including a score of Indians, and about as many of Mexican origin from New Mexico; then there are some fifty Easterners—almost all graduates of Harvard, Yale, Princeton, etc.—and almost as many Southerners; the rest are men of the plains and the Rocky Mountains. Three-fourths of our men have at one time or another been cowboys or else are small stockmen; certainly two- thirds have fathers who fought on one side or the other in the Civil War.” Although authorities offered Roosevelt command of the regiment, the neophyte soldier worried that his military inexperience might adversely affect the men. He suggested that Colonel Leonard Wood be the commander instead, with Roosevelt serving as his second in command.

Roosevelt’s refusal to accept command was admirable, but other politicians worried that in heading to Cuba he was thinking first of his own ambitions. A rousing show in a brief encounter might cement Roosevelt’s name as a man to watch for the presidency. One administration official in Washington concluded that Roosevelt, inexperienced in the rigors of combat, would emerge with a sullied reputation, but hedged, “How absurd all this [criticism] will sound if, by some turn of fortune, he should accomplish some great thing.”

The ships departed from Florida on June 14 for the six-day voyage to Cuba. Shafter landed the men 15 miles east of Santiago at Daiquiri. Once ashore, his men started to advance to Siboney, seven miles from Santiago, in preparation for an assault on Santiago itself. The Spanish commander in Cuba, General Arsenio Linares, had 36,500 soldiers at his disposal in Santiago, but he immediately tossed away the advantage of numbers by dispersing the men in a series of strongpoints instead of concentrating them along the only jungle route available to the Americans. Linares hoped to delay the enemy long enough for Cuba’s natural allies—yellow fever and dysentery—to take their toll. He also hoped that help would arrive before the Americans. A relief column led by Colonel Frederico Escario had departed Manzanillo and started toward Santiago through 160 miles of thick jungle. The 3,752 soldiers in his column could swing the scales toward Spain—if they arrived in time.

Shafter, worrying about Spanish reinforcements, was eager to get his men going as quickly as possible. Cuba’s rainy season, frequently interrupted with ferocious hurricanes and lashing winds, was due to start any day, and he knew that it was only a matter of time before tropical disease reduced his numbers. On June 23, two regiments under the command of Brig. Gen. Henry W. Lawton left the beaches and headed toward Siboney. On June 24, American units advanced in single file toward the crossroads of Las Guasimas, where information indicated that 1,500 Spaniards waited. The Spanish commander on the scene, General Antero Rubin, had orders to mount a minor delaying action to harass the advancing American forces, then fall back to Santiago to avoid being cut off from the bulk of Linares’s troops. Linares intended to stall his opponent at Las Guasimas, not stage an open clash.

Newspaper correspondent Richard Harding Davis of the New York Herald described Las Guasimas as “not a village, nor even a collection of houses; it is the meeting-place of two trails which join at the apex of a V.” The Spanish defenders, dug in along the crest of a hill, peered down on the road below as the Americans assembled before them. Roosevelt and the Rough Riders were to attack along a trail one mile to the left while the 1st Cavalry and 10th Cavalry charged up the main road.

As the Americans neared Las Guasimas, the Spanish defenders unleashed a thunderous volley. Bullets whizzed through leaves and thudded into trees and the ground. Sergeant Hamilton Fish, the son of a prominent politician, dropped dead in the opening seconds, and bullets felled six other Rough Riders in the next few moments as men scurried for cover. The Rough Riders took cover so hastily among the thick jungle covering that Roosevelt feared that he would lose touch with his men. Davis wrote that entering the foreboding canopy was “like forcing the walls of a maze. If each trooper had not kept in touch with the man on either hand he would have been lost in the thicket.”

The Rough Riders tried to locate the origin of the firing, but the Spaniards, buttressed by their knowledge of the terrain, kept well out of sight. They also enjoyed the advantage of using smokeless powder, which left no lingering white trace in the air to indicate where they were hidden. Roosevelt courageously stood erect in the midst of the action, directing return fire and somehow avoiding the deadly steel bullets, although one struck a tree only inches from his cheek and splattered bark splinters into his face.

Finally, Davis spotted a line of Spaniards crouched along the summit of a nearby hill. Roosevelt directed the Rough Riders to concentrate their fire at that point, and a barrage of American bullets soon forced the defenders to flee. At that moment, 900 American soldiers, including the Rough Riders and the black troops of the 10th Cavalry (the famous Buffalo Soldiers), charged the Spanish positions. The Rough Riders swerved to the right flank and rear while the other soldiers charged directly at the Spanish lines, now beginning to fall back as Rubin had intended. The 10th Cavalry mounted a deadly enfilading fire as American units scrambled up the hill, crashed the line of defense, and gained the top of the hill. Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler, a former Confederate cavalry officer, was caught up in the enthusiasm of the moment. “Come on, boys!” he shouted. “We’ve got the damn Yankees on the run!”

The American press hailed Las Guasimas as a glorious victory, even though the Spanish had inflicted the greater number of casualties. The Americans lost 16 dead and 52 wounded at Las Guasimas, against Spanish losses of 10 dead and 25 wounded. Had Rubin held his ground and fought, the tally could have been far higher. The American advance would have been delayed, which in turn would have given reinforcements time to reach Santiago. Spanish confidence would have soared. As it was, American optimism, rife before Las Guasimas, had received a sobering shock. The Cuban campaign was not going to be as simple as most had predicted. A growing number of American troops realized that they faced a professional foe. “Some of these fellows will find out sometime or other that a handful of Americans cannot clean out the whole Spanish Army,” wrote one officer to his wife after Las Guasimas. His words would prove prophetic.

Following the encounter at Las Guasimas, the Americans paused for a few days to regroup and allow time for needed supplies to reach them. The supply system, however, could not rapidly move equipment along the solitary path, which was little more than a crude trail hacked out of the jungle. Food and ammunition piled up on the beaches, while only a trickle of material arrived at the front. “It was simply impossible to get the bare necessities of life to those men,” complained Shafter.

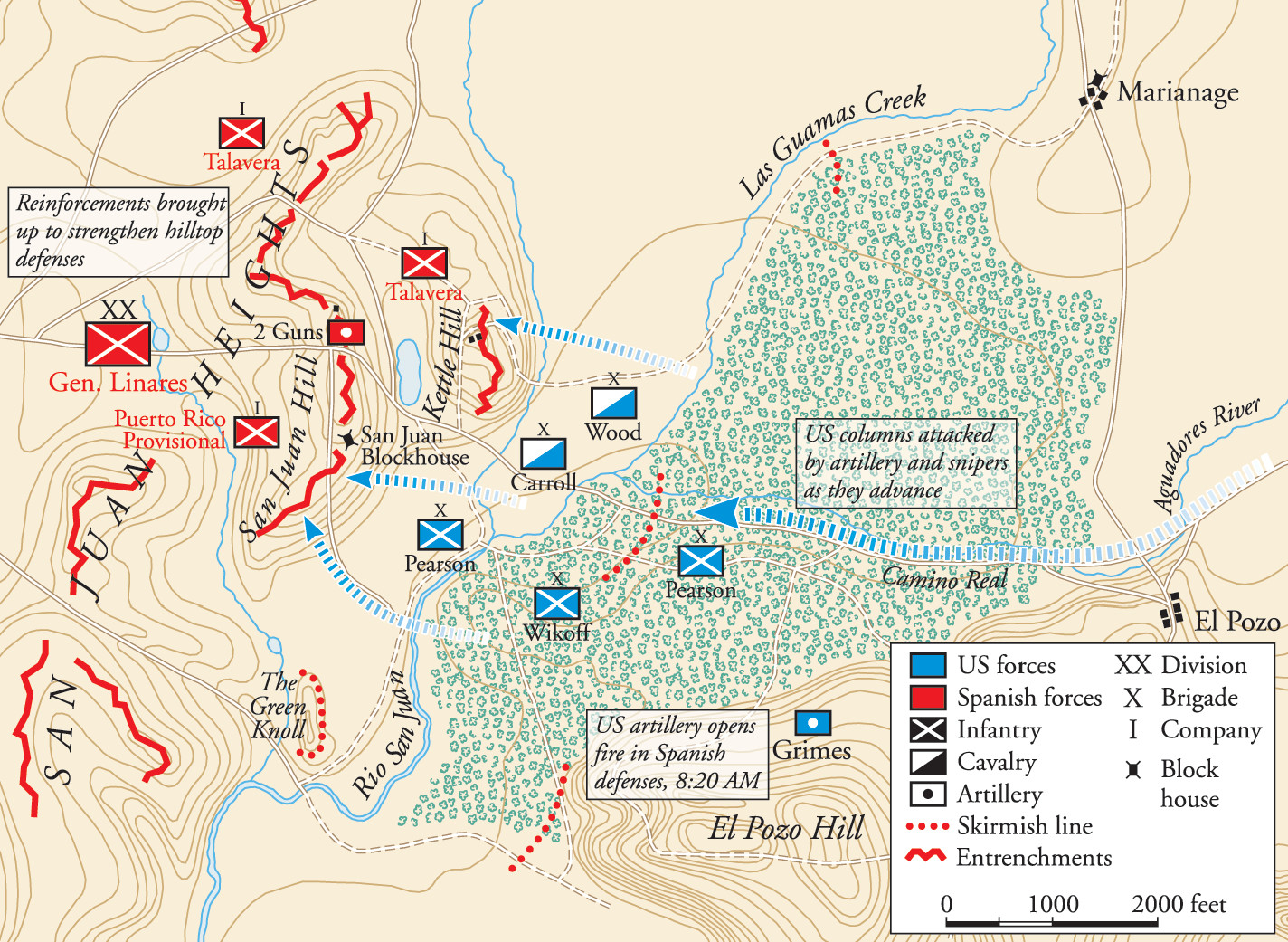

The American commander could hardly have selected worse terrain upon which to stage a battle. The road running through the jungle and leading to the San Juan heights crossed water four times, the final time at the San Juan River. Several hundred yards beyond lay two rises—125-foot-high San Juan Hill and the smaller Kettle Hill to its right. To reach the hills, Shafter’s forces would have to cross the San Juan River under fire, move along the narrow jungle road for 400 yards, then advance toward the heights across an open meadow with waist-high grass. Three and a half miles to the northeast stood the village of El Caney, defended by another group of Spaniards.

Shafter opted for a three-pronged attack. The battle would begin with Lawton’s division of infantry, backed by an artillery battery, charging the defenses at El Caney to eliminate the threat to Shafter’s right flank. Two hours later, the main force, including Roosevelt and the Rough Riders, would move against San Juan and Kettle Hills. By the time this force crossed the river and reached the meadow, Lawton’s men presumably would have arrived to reinforce the attackers. In the meantime, a group of Cuban insurgents would block the road west of Santiago to prevent the reinforcements from reaching Linares.

The terrain favored the defenders. The road disappeared into thick jungle one mile before the meadow, forcing the Americans into a laborious advance before reaching their jumping-off points. A second trail, not discovered by Shafter until the advance had started, split from the main track and broke into the clearing 1,000 feet to the southwest. Knowing that these two routes offered the only avenue for the Americans, the Spanish trained their rifles and artillery on the area. One American officer warned, “The enemy knows where those two trails leave the wood. They have their guns trained on the openings. If our men leave the cover and reach the plain from those trails alone they will be piled up so high that they will block the road.” Despite the risks, Shafter felt that he had no choice but to mount a frontal assault on the heights. Any other tactic would take too long, exposing his men to both the Spanish reinforcements heading in from the west and the main, if invisible, enemy already on the ground—disease.

While Shafter formulated his plans, his soldiers waited impatiently for the supplies to slowly reach the front from the ships back at Daiquiri. Few men wanted to wait any longer. Correspondent Davis wrote that the soldiers could see the enemy strengthening their defenses, a spectacle that caused many to wonder why they did not attack immediately. “For four days before the Americans captured the same rifle-pits at El Caney and San Juan, with a loss of two thousand men,” Davis wrote, “they watched these men diligently preparing for their coming, and wondered why there was no order to embarrass or to end these preparations.”

Roosevelt wondered along with the troops. The enforced inertia frustrated the vigorous New Yorker, who wished that someone—anyone—would step to the forefront and take control. When he finally received orders late on June 30 to move up to the advance positions, Roosevelt and the Rough Riders could only proceed at a snail’s pace. “The heat was intense as we passed through the still, close jungle, which formed a wall on either hand,” wrote Roosevelt. According to Davis, few trails could have offered a worse approach: “The trail was a sunken wagon road, where it was possible, in a few places, for two wagons to pass at one time, but the greater distances were so narrow that there was but just room for a wagon, or a loaded mule-train, to make its way. The banks of the trail were three or four feet high, and when it rained it was converted into a huge gutter, with sides of mud, and with a liquid mud a foot deep between them.”

The slow progress prevented men from arriving at their designated positions until after midnight, which meant that few troops got adequate rest the night before the assault. After seeing that the men were encamped, Roosevelt and Wood sat quietly in their tent, pondering what the next dawn would bring. “We did not talk much,” wrote Roosevelt, “for though we were in ignorance as to precisely what the day would bring forth, we knew that we should see fighting and I suppose that, excepting among hardened veterans, there is always a certain feeling of uneasy excitement the night before the battle.”

The restless night was broken when orders arrived stating that the units should begin moving to their lines at 4 am. The massive camp came suddenly to life. Soldiers washed down hardtack and beef jerky with lukewarm coffee, then gathered with their units and started filtering along the narrow path. Their actions reminded Davis of the cramped confines of a New York setting. “It was as though fifteen regiments were encamped along the sidewalks of Fifth Avenue,” he wrote, “and were all ordered at the same moment to move into it and march downtown.”

One man remained in his tent a mile back. General Shafter’s immense size, combined with Cuba’s weltering heat and humidity, had brought on a debilitating attack of gout. In his place, the commander dispatched Colonel Edward J. McClernand to an observation post at El Pozo. McClernand would then relay Shafter’s orders, transmitted via a telephone line, to Lieutenant John D. Miley, who waited near the front on horseback to rush the orders to the appropriate officer. The cumbersome arrangement would impede the attack in the opening hours, causing unnecessary casualties among the waiting soldiers.

Shafter turned his attention to the second of Linares’s three defensive lines. This one ran through the village of El Caney and the ridges of two hills in front of Santiago—San Juan Hill and Kettle Hill. Six miles northeast of Santiago, El Caney featured six wooden blockhouses and one stone fort, held by 521 Spaniards under General Joaquin del Rey and ringed with trenches and barbed wire. Before Shafter could seize San Juan and Kettle Hills, the last obstacles before Santiago, he would have to eliminate El Caney and remove the threat to his right flank and rear. Shafter estimated that Lawton’s 5,400 men could take the village in two hours, after which time Lawton’s men could turn to their left and join the subsequent attack against San Juan and Kettle Hills.

American infantry had reached a ridge 1,500 yards distant from the stone fort when they saw a handful of Spanish guards. The invaders, afraid that their presence would be detected too soon, quickly took cover to avoid being spotted. “I remember so vividly how concerned we all were lest the Spaniards get wind of our approach and run,” wrote correspondent Caspar Whitney. “Later in the day, we began to wonder if they were ever going to run.”

American artillery opened the fighting at 6:35 am. Correspondent John Fox, Jr., wrote of the first shell, “You could hear that awful hiss so plainly that you seemed to be following the shell with your naked eye; you could hear it above the reverberating roar of the gun up and down the coast mountain; hear it until six seconds later a puff of smoke answered beyond the Spanish column where the shell burst.” Hundreds of white hats suddenly appeared just above the trench line, indicating that Spanish soldiers were ready to repel any advance. At 7 am, American infantry moved forward and opened a heavy fire from 600 yards away. The Spaniards replied with their own volleys, creating a sound that echoed through the area. “It began as corn begins to pop, irregularly and with pauses,” wrote correspondent Frank Norris. “Then it gathered volume and rippled and rolled and spread till it awoke to a great echo somewhere in a little gully of the hills.”

The furious American fire had little effect on the Spanish reply, which slowed the American advance to a few yards at a time. Accurate Spanish fire, especially from snipers in trees and sheltered in cottages and blockhouses, forced Lawton’s infantry to crawl along the ground through tall grass and bushes. “They knew every range perfectly and picked off our men with distressing accuracy if they showed as much as a head,” wrote an infantry officer. The Americans fired back, but as they rarely could see their targets, their bullets had little effect.

At 7 am on the day that Roosevelt later labeled “the great day of my life,” American infantry started moving through the dense foliage toward the San Juan River. Once in position, they were to await orders from Shafter to cross the river, charge across the meadow beyond, push through the barbed-wire barricades, and attack the Spanish trenches and blockhouses atop San Juan and Kettle Hills. An already oppressive heat that would register 100 degrees later in the morning made their task even more difficult.

American artillery in front of San Juan Hill opened fire at 8 am, producing a thunderous reply from the Spanish. As Roosevelt watched with Wood, a shell exploded above, sprinkling the Rough Riders with shrapnel. One piece struck Roosevelt on the wrist and raised a bump the size of a hickory nut. Roosevelt moved his men off the high ground near the artillery to the hill’s far side to avoid another such occurrence. As the artillery duel raged, American infantry continued to move toward the river. The narrow trail, shrouded by the dense jungle foliage, slowed their movement.

While the Americans had little knowledge of the terrain—Shafter had declined to send out reconnaissance patrols ahead of the battle—the Spanish knew every turn in the trail. Riflemen from the heights and snipers in trees mounted a deadly fire on the Americans simply by shooting blindly into the jungle. “Overhead the clicking and buzzing noises had become more definite,” recalled one soldier. “The Spaniards were firing blindly through the jungle and going high. The first high bullets had been a thrill. Now the bullets were proof that someone was trying to kill us, each one of us individually, and in a highly personal way.”

A large observation balloon, manned by daredevil Lt. Col. George Derby, served as an excellent target for Spanish marksmen, whose bullets quickly whizzed through the air in its direction and sprayed the American troops below, including Roosevelt’s, with spent rounds. Lieutenant John J. “Black Jack” Pershing, who would later rise to top command during World War I, quickly moved his 10th Cavalry out of harm’s way. Little seemed to be going right, and when the American troops could not reach their proper positions by 10 am, the assigned time to start storming the hills, the attack had to be postponed.

Brigade commanders futilely tried to reach Shafter, ill in his tent far from the scene. Miley waited for word from McClernand, but none came along the congested trail. Confusion marked the moments immediately before the assault, hardly a comforting notion for officers and infantry about to stake their lives on a massed assault. “Our orders had been of the vaguest kind,” Roosevelt wrote later, “being simply to march to the right and connect with Lawton—with whom, of course, there was no chance of our connecting. No reconnaissance had been made, and the exact position and strength of the Spaniards were not known. A captive balloon was up in the air at this moment, but it was worse than useless.”

Back at El Caney, the American attack remained stalled. Infantry advanced slowly through the tall grass, but accurate Spanish fire forced them to keep their distance from the trenches and barbed wire. A fight that Lawton believed would last two hours had now taken four, with little progress to show for it. Frustration confounded the Americans facing San Juan Hill. They had orders to seek cover wherever they could and hold their fire, despite the casualties suffered from Spanish riflemen. The soldiers impatiently remained in their positions along the river and on the trail, wondering when the command to cross the meadow would relieve them from the agonizing delay. Heavy congestion along the path backed up the line of soldiers filtering to the front for one mile.

“It was during this period of waiting that the greater number of our men were killed,” reported Davis. “For one hour they lay on their rifles staring at the waving green stuff around them, while the bullets drove past incessantly, with savage insistence, cutting the grass again and again in hundreds of fresh places.” Spanish riflemen hidden in trees fired at will, their bullets tearing into the Americans from all sides.

The men could not fall back along the crowded road, but to remain where they were for much longer meant death or injury. To Davis, the Americans were trapped in “a chute of death from which there was no escape except by taking the enemy who held it by the throat and driving him out and beating him down.” The soldiers labeled the junction where the road crossed the river “Bloody Bend” because so many of them were shot at the crossing.

At 11 am, Roosevelt finally received orders to take his Rough Riders across the river, march half a mile to the right, and then wait for further orders. Roosevelt, eager to move as far away from the balloon as possible—it was still drawing intense fire—quickly led his men to a sunken lane at the far right end of the American line. He and his men settled in for another long wait. Although the lane offered some protection, the Rough Riders were still at risk. A popular officer, Captain William O. “Bucky” O’Neill, who believed that an officer should never take cover or show fear, casually strolled about exhorting the men. The other Americans begged him to get down—one sergeant warned, “Captain, a bullet is sure to hit you.” O’Neill, who had been a western sheriff, mayor, and scout, laughed off the warning. Puffing on a cigarette, he replied, “Sergeant, the Spanish bullet isn’t made that will kill me.” As O’Neill turned, a bullet struck him squarely in the mouth and exited the back of his head, killing him instantly.

Relief arrived when the officer in the balloon spotted a second trail meandering through the jungle to the left of the main path. Blocked by vines and deep undergrowth, the second path nevertheless relieved the congestion that had cost the Americans precious time and soldiers. With two avenues to the river and meadow, Shafter’s units could move a bit faster, but the narrow roads still became clogged with men and equipment. Spanish fire killed Brig. Gen. Charles A. Wikoff as he led his brigade across Bloody Bend and deployed to the left. The next in command, Lt. Col. William S. Worth, took over, but he too fell from wounds five minutes later. A third officer, Lt. Col. Emerson S. Liscum, stepped up, but he was shot down within five minutes. Finally, an officer from a nearby unit, Lt. Col. Ezra P. Ewers, led them into line.

In all, 400 Americans were killed or wounded crossing the river and moving forward. The wounded lay in the tropical sun, suffering from heat and thirst as well as pain. To no avail, a frustrated Roosevelt sent a stream of messengers back to locate Miley and see if he could start to advance. He was about ready to take matters into his own hands when, around 1 pm, the command finally arrived to start the attack. Miley, who had heard nothing from Shafter, had sent the order on his own initiative.

Roosevelt immediately leaped onto his horse, Little Texas, and began what he later termed his “crowded hour” by moving the Rough Riders toward Kettle Hill on the American right. He reached a line of Regular Army cavalry in front, whose officer seemed unwilling to go forward. Seeing the hesitation, Roosevelt remarked that if the cavalry was just going to stay where they were, they at least should step aside and let his men through.

Roosevelt moved to the head of the Rough Riders and, riding back and forth along their line, shouted encouragement to the men as they stepped forward. Stunned newspaper correspondents and foreign military observers watching the charges against San Juan and Kettle Hills doubted the maneuver would succeed. “It is very gallant,” said one observer, “but very foolish.” Another added, “By God, it’s plucky! But they can’t do it! It will simply be a hell of a slaughter with no good coming out of it.”

Richard Harding Davis later wrote that the charge up Kettle Hill bore little resemblance to paintings that later heralded the action. Rather than an entire unit advancing in unison, flags snapping in the breeze and bayonets glistening in the sun, “they were so few. It seemed as if someone had made an awful and terrible mistake. One’s instinct was to call to them to come back. You felt that someone had blundered and that these few men were blindly following out some madman’s mad order. It was not heroic then, it seemed merely terribly pathetic. The pity of it, the folly of such a sacrifice was what held you.”

A few small groups of soldiers marked the advance, and behind them followed single lines of men, moving slowly through the high grass. When Roosevelt spotted one man cowering in a bush, he peered down and asked, “Are you afraid to stand up when I am on horseback?” Before the man could reply, a bullet passed through him lengthwise and killed him. To Roosevelt’s left charged the 9th and 10th Cavalry, including Pershing. Gradually, the men rose and headed toward Kettle Hill, halting only to shoot as they ran forward cheering.

Spanish defenders started falling back toward the lines closer to Santiago in the face of the impetuous charge. Forty yards from the summit, Roosevelt encountered barbed wire and leaped off his horse. He and his orderly, Private Henry Bardshar, ran ahead of the others, shooting and yelling. Roosevelt watched as Bardshar fired at two Spaniards, who fell to the ground. As a handful of remaining Spanish soldiers fled, the two men reached Kettle Hill’s summit, then turned to see the rest of the Rough Riders and the 9th Cavalry swarming up the slopes.

The defenders, seeing waves of Americans rushing toward them rather than resting like sitting ducks along the river, quickly abandoned their positions. The American correspondents watching from the rear caught the excitement of the moment, depicting the charge in glorious terms and painting Roosevelt as the day’s savior. Davis, a personal friend, stated that Roosevelt “was, without doubt, the most conspicuous figure in the charge.” He added that “Roosevelt, mounted high on horseback, and charging the rifle-pits at a gallop and quite alone, made you feel that you would like to cheer.” Another correspondent claimed, “There was the stuff of which heroes are made in the bespectacled volunteer officer, charging the Spanish earthworks at a gallop, with a blue polka-dotted handkerchief floating like a guidon from his sombrero.”

In the meantime, the American forces battling at El Caney still struggled to gain yards. One shell knocked the Spanish flag from atop the stone fort, but otherwise the men had little to cheer about. Flies buzzed around dead bodies and land crabs waited for movement to cease before crawling in for a feast. By 2 pm, hours after the assault was to have ended, Lawton’s attack remained stalled, the bulk of his 5,000 men stymied by accurate Spanish fire. “I was fearful I had made a terrible mistake,” Shafter wrote later.

The charge up San Juan Hill was similar to Kettle Hill, consisting of small groups of soldiers advancing a few yards at a time against heavy Spanish fire from snipers and men in trenches. Officers and men fell from gunshot wounds or the debilitating effects of the sun. In an effort to alleviate the situation, Roosevelt ordered his men on Kettle Hill to direct their fire in support of Brig. Gen. Hamilton S. Hawkins, who led his brigade across the grassy open ground toward the heights. Lieutenant Jules Ord, brandishing a saber in one hand and a revolver in the other, exhorted the men of the 6th Infantry as they reached the hill. Running at the head of the group, Ord alternately ran forward a few yards, fired his pistol, and shouted encouragement to the soldiers behind. Gradually, they inched toward the crest.

The Americans made little progress against the defenders at San Juan Hill until 1:15, when three Gatling guns commanded by Lieutenant John Parker were brought forward and opened fire from 600 to 800 yards. The guns pumped 2,400 bullets per minute toward the Spanish trenches, pinning down the defenders and punching holes in their lines. As American infantry reached the crest of San Juan Hill, Parker and Roosevelt lifted their covering fire. The Americans halted at the top and fired into the trenches, then dashed across and headed toward the blockhouse. The attack quickly turned into a rout, with the surviving Spaniards fleeing toward Santiago.

The Rough Riders poured across the interval to join their cohorts at San Juan. As Roosevelt and another soldier reached the trenches, two Spaniards suddenly leaped up and shot at them from close range. The bullets missed, but as they turned to flee Roosevelt shot and killed one of the defenders. Roosevelt continued forward until he arrived at the crest, from where he could look below and see the city of Santiago. Other Americans, realizing that victory was theirs, drove the Stars and Stripes and their yellow silk cavalry flags into the ground and waved their hats in triumph. A few Spaniards attempted to reform for a counterattack, but fell back when they saw more Americans reach the crest. Davis, who had watched the Americans rush across the meadow, storm up the hill, and plant their flags along the crest, observed, “From these few figures perched on the Spanish rifle-pits, came, faintly, the sound of a tired, broken cheer.”

Victory had been attained at San Juan Heights, but fighting still engulfed the opponents at El Caney for another three hours. Finally, at 4:15 pm, more than six hours after Shafter expected Lawton to have taken the village, the Spanish yielded the site after gallantly delaying the numerically superior Americans. The retreating Spanish left many dead and wounded behind. Bodies littered the trenches and filled the stone fort, blood covered the inside walls. “The dead were everywhere,” wrote Norris. “The air was full of smells—the smell of stale powder, of smoke, of a horse’s carcass two days unburied, of shattered lime and plaster in the blockhouse, and the strange, acrid, salty smell of blood.”

The Americans had paid dearly for breaching the Spanish defenses blocking the way to Santiago. The actions cost the United States 205 dead and 1,180 wounded, while the Spanish suffered 215 dead and 376 wounded. Part of the reason for the heavy casualties lay in the unbearably hot conditions in which the battle was fought, but a large portion of blame rested at Shafter’s feet. Rather than trying to seize El Caney from the front, he could have tied up the Spanish defenders with a small force, which would have allowed him to place more men at San Juan and Kettle Hills. Adequate reconnaissance before the battle could have detected the second path through the jungle and relieved the heavy congestion that stacked up the American infantry and made them easy targets for Spanish snipers. In his weakened condition, Shafter should have relinquished command to a senior officer on the scene.

The Americans who seized San Juan and Kettle Hills gained great recognition from the citizens back home, who eagerly devoured news accounts of the fighting submitted by Davis and other correspondents. When the armies returned to the country after the Cuban campaign ended in total American victory a few weeks later, they enjoyed a heroes’ welcome. To a lesser extent, the African American soldiers received adulation as well. Pershing stated proudly that his black soldiers “had fought their way into the hearts of the American people.” Unfortunately, once back on American soil, the soldiers again faced the racial bigotry that still marked American society.

Since the action at San Juan Hill involved more troops than Kettle Hill, the two actions were frequently combined in the public mind into one assault. Consequently, Roosevelt became known as the hero of San Juan Hill, even though he had performed his most courageous acts of leadership at Kettle Hill. Whichever hill he had captured, Roosevelt astutely parlayed his newfound fighting reputation into a political career that began as governor of New York and culminated in the presidency of the United States. July 1, 1898, had proved, indeed, to be a great day for Theodore Roosevelt.

I have been to San Juan Hill and seen the statues and cannons in the park at the top of the hill. Very beautiful and impressive.