By Don Hollway

The Age of Chivalry brings to mind knights in shining armor and damsels in distress, along with traveling troubadours and minstrels singing chansons de geste, “songs of deeds,” telling of feats of arms and labors of love. One of the first, and the most famous, was La Chanson de Roland, “The Song of Roland,” the Frankish hero who, with his boon companion Oliver, was the favorite of his king Charlemagne. For a thousand years readers and audiences have thrilled to the moment when Oliver, on hearing the blaring war horns of the approaching Saracen army, warns his friend that they and their very few men face a battle against overwhelming odds, and very likely their deaths, to which Roland replies gamely, “God grant it be so.”

Written in the latter half of the 11th Century, Roland’s chanson told of events from the late 8th. Over those 300 years Europe had changed almost as much as it had over the preceding 300, after Rome fell to the Goths in AD 410 and the Western Roman Empire collapsed. What had been Roman Gaul had been rent into separate realms that no longer exist as such: Neustria, Austrasia, Burgundy, Aquitaine, Gascony, more. From these the Franks, a Germanic people once loyal to Rome, slowly wrought a new empire in their own barbarian manner. Their kings Childeric, Clovis, and Carl (later famed as Charles Martel, the Hammer) united the Frankish tribes, halted the Muslim expansion out of Spain and gave rise to the Carolingian Dynasty, named for Martel’s grandson Carolus, called Magnus—Charlemagne, Charles the Great. Crowned King of the Franks in AD 768, he made it his life’s work to resurrect the old Roman Empire.

Progress, however, came at a cost to peace. Almost every spring the king assembled his army for an expedition to the far reaches of his realm, in order to expand his borders at the expense of his neighbors, the Lombards and Saracens in the south, the Saxons in the east, and the proto-Viking ScandinaQvians in the north. The Franks rode horses on those long marches to the frontiers, and many eventually did not dismount even to fight. This tradition of horse-borne warfare, inherited from their forefathers’ service as mercenary cavalry to the Romans and retaught to them by the Hunnish hordes of mid-millennium, created a warrior elite in Charlemagne’s army. The concept of knights and knighthood was still in the future—the stirrup and high-cantled war saddle were only recent adoptions, and full-body plate armor would not be invented for some centuries yet. A chain-mail hauberk requiring up to 1,000 man-hours to weave was fantastically expensive; only the wealthiest lords and their men could afford more than a byrnie of leather and metal scales. Yet the distinction of mounted, armored men fostered something like the old Roman equestrian class, the comites palatinus, counts of the palace, high officials of the court. From these, it was said, came the king’s chosen few—12 to be precise, a number central to Christian theology—an inner circle to become legendary, near-mythical, akin to King Arthur’s Knights of the Round Table or Christ’s Apostles, whom later minstrels praised as Charlemagne’s Paladins. Foremost among these—at least, to hear the troubadours tell it—was the lord Hrothiland, (“famed of the land” or “famous and brave”in Frankish). More popularly, he would become immortal with the French name Roland, le Preux, “the Valiant.”

Though documentation is sparse, Roland was an actual person. The oldest form of his name, the West Germanic “Rotlan,” appears on the witness roll of a Carolingian document dated to AD 776, and no later than 790 on a Frankish silver denier coin. His place in history is secure, even if most of what was written down about him were tall tales.

In the so-called Dark Ages few people were literate, even among the nobility. The chansons became mass entertainment, the “bestselling novels” of their day. Their authors and re-tellers never hesitated to fictionalize and exaggerate their heroes’ exploits to suit their stories. Though it was written a century after his personal chanson, and 400 years after his death, Roland appears as a lad in the Chanson d’Aspremont, about a battle at modern Aspromonte, along the Strait of Messina in Calabria, southern Italy. This would have been during Charlemagne’s AD 773–776 campaign against the Lombards who then ruled the peninsula, though like Roland’s the chanson casts Saracens as its villains.

As shall be seen, this is a common theme, for Roland’s song was written prior to the First Crusade and embellished during it, and the song of Aspremont in anticipation of the Third Crusade, both in part as propaganda against the later enemy, Islam.

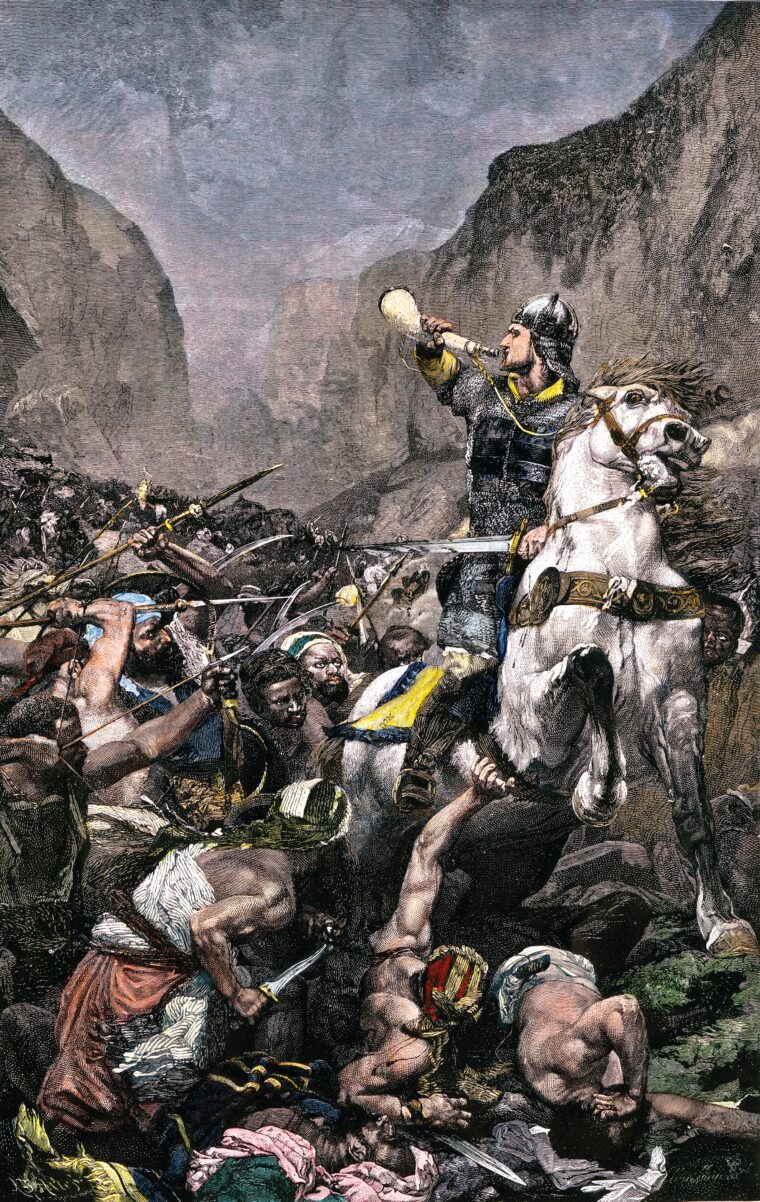

for help while holding his sword Durendal while mounted on his horse Veillantif. The geologic feature “Roland’s Breach” is in the background.

As King of the Franks Charlemagne, determined to expel “Saracen invaders”—i.e., Lombards—from Italy, sends another of his Paladins, Archbishop Tilpin of Rheims (who didn’t actually become an archbishop until years later), to confine Roland and his friends in their castle at Laon: “I cannot take young boys on this business.”

That Roland was said to be Charlemagne’s sister’s son surely had something to do with royal concern. The king had three sisters, Adelheid (born 740), Bertbelle (745), and Gisela (757). It’s been surmised, admittedly on scant historical basis, that Berta was Roland’s mother, and furthermore that his father was Milo or Milon, a nobleman of Andecavis, modern Angers in western France, who died in battle soon after his son’s birth.

At any rate Roland, as medieval champions are wont, is having none of his uncle’s enforced safety. In the best action-hero tradition, on hearing the royal army march through Laon, he and his friends knock their guard senseless and set off after the army. It does not befit highborn lads to march on foot, however, and as soon as they catch up to the army’s rearguard Roland tells his companions, “Friends, shall we walk like serfs all the way to Calabria? See those riders ahead of us? Let us catch and pull them off, and get ourselves horses.”

That these were Bretons, Charlemagne’s allies, did not enter into a warrior’s thinking. Might made right, as was proven when the boys rode into the royal camp and the king and assembled lords laughed to hear of their exploits. It did not qualify them as fighting men, but they tagged along with the army as it marched down the length of France and over the Alps into Italy. (High mountain passes would play a critical role in Roland’s story.)

Charlemagne laid siege to the Lombard king in Pavia, deposed him, and chased his son into exile. In Rome the Frankish king was welcomed by Pope Adrian I as the new King of the Lombards. That was an insufficiently exciting climax, though, for the authors of the chanson, which casts the enemy as the fictional Saracen king Agolant and his son Aumon, and after the Franks defeat a Muslim force three times their number at Aspremont, has Charlemagne face Aumon in single combat, winner take all.

The purposes of the story naturally required Aumon to be a great warrior. His war horn, Olifant, was said to be carved from elephant tusk, or even unicorn horn from India. His Arab steed, in Italian versions of the story called Briadoro or Brigliadoro, “Golden Bridle,” was described in the songs as a “swift courser” (warhorse). His sword, Durandal (of various meanings in Old French, Breton or Arabic), was a legend in its own right, said to have been handed down from Hector of Troy, or alternatively forged by the fabled Wayland, master blacksmith of Germanic heroic myth, from the same steel as Charlemagne’s sword Joyeuse, completely indestructible and capable of hewing through stone.

Charlemagne’s helmet, however, has an impervious stone set in the nasal, which is all that saves him in the fight. Finally Aumon tears the helmet off and is about to deliver the death blow when who should ride to the rescue but none other than Roland: “Milord uncle, what are you doing? It is I, your nephew Roland, your favorite! Would we ever be welcome at court if we can’t tame one pagan hawk?”

He has armed himself with a warhorse, armor and helmet taken from battlefield dead—all except a sword, for as he well knows he is not yet worthy to carry one. Instead, with a cudgel or quarterstaff, he strikes Durandal from Aumon’s hand and proceeds—with a medieval savagery that would seem to defy chivalric code, but doubtless delighted its Crusader audience—to club the Muslim prince to death and claim his property as trophies of war: “Young Roland gained his Olifant this way, and Durendal with which he won such fame, and the swift horse he named Veillantif [Vigilant].”

These would have indeed been trophies fit for a hero. Arab steeds, though smaller than stout northern mounts, were famed for their speed, agility and endurance. And when true welding was yet in the future, Northern European swords were “pattern welded” of white-hot iron rods twisted together, beaten flat and ground to an edge, with unpredictable results. Middle Eastern blades of damascened crucible steel and Central Asian cast blades had a reputation for superior hardness, sharpness and durability. And as the crescent scimitar symbolic of Islam would not become popular in the Muslim world until the next century, Durandal would have been a cruciform sword of the finest quality, eminently suitable for a Christian champion.

The Chanson d’Aspremont is fantasy, of course, written when Roland and Charlemagne had already become legend, in what modern audiences might recognize as a kind of prequel or superhero origin story. Another chanson, Girart de Vienne, by the 12th century French cleric and poet Bertrand de Bar-sur-Aube, told how Roland and Oliver came together.

It has Charlemagne laying siege to rebellious Count Girart in his city of Vienne on the Rhône River—an event that actually happened about a 100 years after Roland’s day, when the “Emperor Charles” in question was Charlemagne’s grandson, Charles the Bald. In the narrative, when the siege proves inconclusive, the two leaders agree to a duel of champions, Charlemagne’s nephew Roland against Girart’s (probably fictitious) nephew Oliver.

“If you had been beneath Vienne, my lords, when Oliver and Roland faced and fought!” proclaims the song. “There never were two knights as brave before, so bold of heart and so well-skilled in war!” They are said to have battled all day and into the evening, pausing only when Oliver broke his sword on Roland’s shield and accepted another—gold-hilted, bejeweled Halteclere, said to have once belonged to a Roman emperor. Watching from the city walls, Oliver’s sister, the maiden Aude, who naturally admires Roland from afar, prays for both: “Glorious Lord, let Your great mercy flow on these two knights, for I do love them both. Let them neither be maimed or slain as foes!”

And God answers, sending down an angel to part and halt the antagonists. “This feud and fight of yours shall be no more, lords. Not one more blow must be exchanged….

Henceforth in Spain against the race of heathens your fierce prowess shall yet be known and needed. Men shall know well your valor there and see it.” At this Roland and Oliver swear their amity and loyalty for each other, and Roland is betrothed to Aude. Medieval audiences loved it. The Chanson d’Aspremont and Girart de Vienne were the literary blockbusters of their day.

Just a few years after his conquest of Lombardy, an opportunity indeed arose for Charlemagne to again extend his domain to Spain. For once, the enemy really were to be Saracens. The Umayyad Caliphate that had wrested the peninsula from the Goths in the early 700s had in mid-century itself been overthrown in the Middle East by the Abbasid Caliphate, but a generation later their civil war still raged in Spain. The Umayyad emir of Cordoba, Abd ar-Rahman I, was battling the Abbasid wali (governor) of Barcelona, Sulayman al-Arabi. Lacking support from his caliph far away in Baghdad, in AD 777 al-Arabi turned to Charlemagne, pledging his fealty and that of Abbasid cities, including their regional capital at Saraqusta, modern Saragossa.

The chance to convert Spain back to Christianity—and vastly increase his territory, manpower and tax base—proved irresistible to Charlemagne. His biographer, the Frankish scholar Einhard, recorded in his contemporary Vita Karoli Magni, “Life of Charles the Great,” that the king “attacked Spain with the largest military expedition that he could collect.”

The Frankish kingdom is thought capable of supporting 100,000 footsoldiers and 35,000 horsemen. The vast majority, however, were employed at garrisons along its vast frontiers and borders, with only about 10,000 available at any given time for offensive operations. For Spain Charlemagne may have assembled as many as 25,000, with a wagon train bearing a three-month supply of food for each man. In the 8th century that was a huge army, but the king recognized that he would have trouble bringing all his forces to bear on this campaign.

The main obstacle was the wall of the Pyrenees Mountains separating France from Spain, in places 11,000 feet above sea level. An invasion could only be accomplished through key mountain passes. The Annales Regni Francorum, the Royal Frankish Annals, a court chronicle of the age, recorded, “King Charlemagne marched to Spain by two different routes.”

He sent his Austrasians, Lombards and Burgundians through the eastern passes under command of his uncle Bernhard of Saint Quentin to support Barcelona, and meanwhile personally led his Neustrian forces through the western range. The two armies would then meet at Saragossa. Part of this great campaign was Roland—“brave Roland,” “great Roland,” “from here to farthest East no knight his equal ever lived”—now with the rank of Brittannici limitis praefectus, Prefect of the Breton Frontier.

Setting out from central France in mid-March, the Franks reached Aquitaine in the southwest within a month. From there an old Roman road led south to the Portum Sicera, modern Cize Pass through the Pyrenees, called the “Gate of Spain.” In those days this was Vasconia, roughly modern-day Gascony in southern France and Navarre in northern Spain. The fierce Vascones—modern Basques—had maintained their independence since Roman times. Four hundred years after Charlemagne and Roland, French pilgrim Aymeric Picaud crossed the mountains by the same route, and found the Vascones little more civilized by the intervening centuries. “They are a barbarian people, different in customs and nature from all other people, extremely evil,” he wrote. “…For a miserable coin, [they] would kill a Frenchman, given the opportunity…. However, they are considered brave in the battlefield.”

In 755 the Vascones, most of whom are thought to have adhered to a pagan religion, had defeated an Umayyad army, and since then had maintained relations with the Christians to their north and Muslims to their south as a balance of power. An alliance of Charlemagne with the Abbasids, however, would leave the Vascones at the mercy of both. It behooved them to side with the Umayyads.

Charlemagne bargained with the Duke of Gascony, Lupus II Otsoa (whose name translates as “Wolf”), exchanging hostages for safe passage over the mountains. Lupus, though, only nominally ruled Vasconia, which was more a patchwork of territories subject to buruzagis, local warlords. They allowed the Frankish army to thread its way unmolested through the high passes, but their neutrality was tested in early June, when the Franks came down out of the mountains to the gates of their chief city, Pamplona.

Founded by the Romans on the site of an ancient Vascone settlement atop a steep riverbank, Pamplona was walled and stoutly defended. These southern Navarrese Vascones may not have considered themselves subjects of the Duke Lupus at all, and were apparently reluctant to submit to an invading king. On his way over the mountains, however, Charlemagne had received the blessing of Pope Adrian, who was said to have sent him the Oriflamme, “Golden Flame,” the red and gold battle flag carried by French kings throughout the Middle Ages. A medieval prophecy claimed the Oriflamme, mounted on a golden lance, would burn and drive Saracens ahead of it. It made Charlemagne’s campaign something of a proto-Crusade, and the Franks evidently brooked no resistance from nonbelievers. A century later the Poeta Saxo, an anonymous Saxon poet in the Carolingian court of East Francia, recorded of Charlemagne, “When he had crossed the first crest of the Pyrenees and had reached Pamplona, which is said to be a fine fortress of Navarre, he took it by force of arms.”

From this base of operations, Charlemagne advanced south to join up with Bernhard at Saragossa. The Song of Roland has its hero boasting to his king of the towns his forces have conquered in Spain, all but a few of which lie on the road from Pamplona to Saragossa, and the city of Valterne (probably the valley of modern Tiermas in Aragon), “sacked by Roland and left in ruins, which for a hundred years was a desert.” If any of this was based in fact, the Muslims would have had looked on the oncoming Franks as invaders rather than allies.

“Arriving from two sides,” reports the Annales Regni, “the armies united at Saragossa.” In mid-July, Charlemagne and Bernhard camped on the bank of the Ebro River before the city walls. Unlike Pamplona, Saragossa was thoroughly Islamic. Its wali, Husayn ibn Yahya al-Ansari, would have received news of Charlemagne’s crusade, and did not consider himself bound by the treaty with the Franks if it required his submission to a Christian king. The previous autumn his city had stood off a siege by the Umayyads, and he still held their general as a prisoner. Perhaps deciding he no longer needed Charlemagne’s support, al-Ansari refused to open his gates.

Charlemagne had come all this way expecting submission, not to mount a siege, for which he had neither the machinery nor the time. Cordoba’s Umayyad emir had sent forces to block the Franks’ retreat east toward Barcelona. On top of that, word came that in the Franks’ absence the Saxons were stirring up trouble at home.

The Song of Roland would have it that al-Ansari, called King Marsile in the poem, offered Charlemagne hostages, treasure and his conversion to Christianity if the Franks would go home. It is something of a trigger incident in the story, for Roland nominates his stepfather Ganelon, the king’s brother-in-law, to bear the royal reply to the Muslims. Ganelon—a character based on the actual Archbishop Wenilo of Sens, who crowned Charles the Bald king in 848 but 10 years later infamously turned traitor—fears death at Muslim hands and accuses Roland of intending it: “If God but grant me safe return, I shall hurl such ill fortune on you to smite your life for now and forever with a curse.”

The chanson has Ganelon striking a deadly bargain with the Muslims for his life: “Together they pledged their faith, to snare Roland and lead him to his death.” And in fact, the Saracens made noises about fealty and handed over their captive Umayyad general as a hostage who could be ransomed to his emir. Charlemagne had to be satisfied with that. “Charles the Great that land of Spain had wasted,” proclaimed Roland’s song, “her castles taken, her cities violated,” but the truth is, this Spanish expedition had turned out to be a losing proposition, netting the Franks little of the promised territory, loot or subjects.

Things got worse. While Charlemagne was occupied with Saragossa, the Vascones’ resolve had stiffened. The chronicles vary—the timelines are confused—but there may have been some kind of battle outside Pamplona. This further evidence of treachery may be why Charlemagne wrought vengeance on the city, so fearsome it was still remembered centuries later. The anonymous Saxon poet recorded, “He went back to Pamplona and completely destroyed its walls lest it became rebellious.”

“Now the Saracens [in this sense meaning both Muslims and pagans] were forced to give up the city, even if they didn’t want to,” recorded a medieval account. Another reported, “The king gave life to all the Saracens who wanted to be baptized, but all those who did not want to be baptized he ordered killed.” And a third claimed, “So much blood was shed of the Saracens that the Christian people waded in the blood. And Charles, all the Saracens that he found in the city of Pamplona, he slew.”

The Franks looted the city. Having done his worst, in August Charlemagne turned north for home.

If anything, the Pyrenees now presented an even greater impediment to the march, for the mountains’ southern slopes are steeper, the Franks were weary from marching back and forth over northern Spain, and their wagon train was laden with stolen treasure. The army, now including that of Bernhard, would be strung out even further, but this time the vengeful Vascones would not be so cooperative. In Roland’s Song Charlemagne seems well aware of the hatred he has left in his wake, fully expects an attack to come from behind, and knows that to face it is practically a suicide mission: “Barons, you see those deep defiles and narrow passes. Decide who will command our rear.”

Roland being still a young lord at this time, the rearguard was in reality probably led by a more seasoned warrior, Aggiardus (in modern spelling, Eggihard). He was Charlemagne’s Mayor of the Palace, his seneschal, equivalent to a modern prime minister or second in command, but curiously received no billing in Roland’s chanson. Its plot line requires treachery on the part of Ganelon. As he had been nominated to go into the Saracens’ den at Saragossa, he now returns the favor, fulfilling his part of the bargain with the enemy by offering up his choice of sacrificial lamb: “Roland, my stepson, whom among your valiant knights you prize the most.”

Though the king sees through Ganelon’s plan —“You devil incarnate, into your heart is come a mortal hate”—Roland would rather risk death than be shamed by refusing. He accepts, assuring Charlemagne, “You can pass through the defiles in safety, and fear no harm from man while yet I live.”

Charlemagne is equally honor-bound to trust his nephew to fate. On the other hand his Paladins, including Oliver and Tilpin, are all eager to share in Roland’s glory. They muster to his white banner and bring up the rear as the army winds its way up into the mountains. “High are the peaks, the valleys murky-dark,” goes the chanson. “The rocks are black, the gorges terrible. The Franks toil through them painfully.”

About 30 miles from Pamplona, and 3,000 feet above sea level, lies Roncesvalles, the “Valley of Briars” (Roncevaux, in French). A mountain meadow sloping up toward the north, it provided an apt campsite for the army on Wednesday evening, August 14th. In the morning, Charlemagne led the vanguard into the narrowing pass. “The king had gone on ahead,” recorded the Poeta Saxo. “That part of the army that was hindered by the carrying of the baggage was behind him.”

The size of the army, and the tightness of the way, was such that the file of marching men stretched out for nearly 11 miles. It was nearly midday before the wagon train could even begin to follow into the single-lane, beech-shrouded defile. Einhard reported, “The army was moving in column, and its formation was much extended, as the narrowness of the pass required.”

The Chanson de Roland would have it that Roland, Oliver, Tilpin and the rest of the Paladins bring up the rear. Meanwhile the Saracen army, claimed in the poem to be 400,000 strong, rides in pursuit. From a mountaintop lookout, Oliver sees them coming. He rides to warn Roland the Franks are outnumbered, advising him to blow the Olifant and summon Charlemagne to their rescue. Roland, however, would rather die than be thought cowardly: “A man should willingly suffer for his lord.”

Archbishop Tilpin gives the Franks final absolution for their sins. They mount and face the enemy charge. Each slays a Muslim prince in turn. Roland and Oliver break their spears in battle, on which Roland unsheathes Durendal, and Oliver Hauteclere. Together the Paladins hew into the enemy. The poet revels in men speared through the spine, struck from the saddle, cleaved in half by Frankish steel: “Roland and Oliver vie with Tilpin in skill and glorious deeds.”

One by one, however, the rest of the Paladins are cut down. Hard pressed by sheer numbers, Roland finally decides to blow the Olifant. Oliver chides him that it is too late now, that neither of them will live to see fair Aude again. This is no time for bickering, says Tilpin: “Roland, blow your horn, so that returning Charlemagne will at least see to it our bodies are given honorable burial rather than stripped and left for carrion.” Roland blows the Olifant so loudly that the king hears it 30 leagues away—that would be 90 miles—and, over Ganelon’s objections, turns back to save him.

It is too late. Oliver dies, speared through from behind. Veillantif is killed under Roland, dead of 30 wounds. Archbishop Tilpin fills the Olifant from a mountain stream to administer a final benediction to Oliver and the rest of the Paladins before falling dead himself. With his last breath Roland strikes Durendal on a stone to shatter its blade, but Durendal instead splits the rock, and God sends his cherubim to bear the dead champion’s soul to heaven. On arrival at the battlefield Charlemagne weeps over his nephew’s body. In France Aude, upon learning her brother and hero are both slain, falls dead herself. For his treachery Ganelon is chained by hands and feet to four horses and torn apart. All very heroic, romantic, tragic and satisfying to medieval audiences, but the reality of the Battle of Roncesvalles was otherwise.

It was not Muslims, but the Vascones who attacked the Franks, and they were not following but already lying in wait for Charlemagne. Einhard recorded, “the Vascones arranged an ambush on the top of the mountain where the thick woods made it perfect for such an attack.”

Unlike the Franks, weighed down by their horses and wagons, armor, heavy shields, lances, swords and axes, the hill tribesmen preferred the azcona, or short spear, and wore little more than woolen cloaks and leathern kilts and sandals. They scaled the heights like mountain goats and waited for the Franks to pass beneath them. North of Roncesvalles the Cize Pass trail narrows to only a little over 10 feet across, winding and doubling back on itself, with steep banks up one side and to the other, equally steep, drops to the valley floor. At one point the nearby river below runs almost beneath the pathway, while above it rises a sheer 130-foot cliff. The Frankish vanguard, with Charlemagne in command, marched through easily enough, but only because the Vascones once again let them, silently awaiting the wagon train full of Pamplona’s treasure before signaling the attack. “When in hiding to capture prey [the Basque] wants to call his colleagues quietly,” recorded the pilgrim Picaud, “he sings like an owl or howls like a wolf.”

It’s not hard to picture the worn-out, footsore Franks trudging along the narrow path, pushing their wagons upslope behind their sweating cart horses and gasping for breath at the high altitude, only to be startled by the trilling, ululating irrintzi, the shrill cry still characteristic of the Basques, echoing in the narrow pass just before a sudden hiss of arrows shooting from the thickly wooded slopes and a shower of rocks tumbling from the cliff tops.

It has become common among historians to dismiss Roncesvalles as nothing more than a skirmish, but the Franks did not think of it as such. They referred to it in Latin as a certamen: battle, war. “The army was frightened,” recorded the Saxon poet, “and thrown into sudden tumult.” Strung out in nearly single file along the trail, the Franks had no cover, no side roads or paths on which to escape. The Annales Regni attests the attack “threw the whole army into confusion.”

Their own arrows and spears, launched upward, could not reach the Vascones. In the maze of mountain walls an oliphant blast would hardly have been heard around the next few bends in the trail, let alone by the king some eight miles ahead. Meanwhile even a few cart horses downed by spears, arrows or a landslide, or wagons smashed by boulders, made a perfect roadblock, completely cutting off the trail and allowing a handful of men to hold off an entire army, let alone the forward half of Charlemagne’s.

Einhard claimed the Vascones “rushed down from their vantage ground into the valley below and threw themselves upon the trailing section of the baggage, and on those who were marching with it for its protection.”

The Annales Regni reported, “Although the Franks were obviously their betters in arms and valor, they nevertheless suffered a defeat due to the unfavorable terrain and the unequal method of fighting.”

In the tight confines of the single-lane battlefield the Vascones’ light gear gave them extra speed and agility over the heavily encumbered Franks. The sheer momentum of the tribesmen plunging downhill into them would have been enough to drive them just a few steps off the trail, which meant tumbling down the steep slopes to be battered to death against the rocks and trees, smashed at the bottom, or drowned in the river. Einhard wrote, “The Vascones attacked them in a hand-to-hand fight and killed them all to a man.”

The Paladins’ horses and armor could not save them in this fight. The Annales recorded, “In this engagement a great many officers of the palace, whom the king had given positions of command, were killed.”

No one actually knows the manner of Roland’s end, glorious or otherwise, because no witnesses survived to tell of it. It is only the seneschal Eggihard’s death, recorded in the chronicles as Thursday, August 15, 778, that so much as marks the date of the Battle of Roncesvalles, and only the dispositions of the dead were left to tell the tale.

The surrounding high peaks soon cut off daylight. As evening fell the Vascones looted the baggage train and, before the main Frankish force could intervene, vanished into the Pyrenees. The Poeta Saxo wrote, “They were very familiar with the heights of the mountains, the retreats of the woods, and the depths of the valleys. Imminent night made it impossible to track them down thus scattered in flight, and so no vengeance could follow.”

If Charlemagne wept over news of the defeat, he did not do it over Roland’s body but from a nearby valley, known thereafter as Valcarlos, which is the closest he got before night fell. The bodies of the Frankish dead were dumped into one of the rock grottoes which riddle the mountains. In later years a church was built over the site, where 1,000 years later the pit was still said to be full of human bones. The Saxon poet wrote, “The fact that so great a crime remained unavenged brought a cloud of sadness over the king’s mind which his many previous successes had made serene,” and the Annales Regni concurred: “To have suffered this wound shadowed the king’s view of his success in Spain.”

In the morning Charlemagne hurried northward to engage those other rebels, the Saxons. He never returned to Roncesvalles or tried to tame Vasconia. In AD 800 he was crowned as the first Western Emperor of the Romans in over 300 years, and in doing so established what some historians have dubbed the “Carolingian Renaissance,” an era of stability, prosperity and learning. He is remembered as the Pater Europae, the Father of Europe. His courtier Einhard called Roncesvalles merely “a reverse which he experienced through the treason of the Vascones on his return through the passes of the Pyrenees,” but it would be the greatest defeat of Charlemagne’s life.

Through the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, right into the Baroque era, Roland’s Song became what modern audiences would call a “tentpole franchise.” By the 12th century it became the Rolandslied, the national poem of the new, Germanic Holy Roman Empire. The 13th century Scandinavian Karlamagnús saga devoted merely a chapter to him; by the 15th he achieved top billing over Charlemagne in the Norwegian Roland og Magnus kongen, “Roland and King Magnus.” The Italians knew him as Orlando in Orlando Innamorato,“Orlando in Love,” Orlando Furioso,“The Fury of Orlando,” and the epic La Spagna,“Spain.” When the story plots began running dry, the 14th century Franco-Venetians even rebooted him as an Arthurian-style knight-errant in Entrée d’Espagne, “Entry to Spain.” Roland transformed into a superhero. Various Basque villages, some 20 miles from Roncesvalles, still boast giant stones said to have been cast there by him in his anger. “Roland’s Breach,” a cleft in the mountains some 9,000 feet up, is said to be where he struck Durendal against the stone, even though it’s some 50 miles from the battle site.

Oliver likely never existed, Tilpin didn’t die at Roncesvalles but lived well into the 790s, and whether Roland’s death was glorious or ignominious matters little. What matters is that he died for something greater than himself, and in a barbarian Europe struggling to re-attain imperial civilization, that set an example. The Song of Roland is less important for its accuracy than for its effect. It inspired medieval French aristocracy, and through them the aristocracies of the Western world, toward the highest goals of honesty, bravery and chivalry.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments