By Arnold Blumberg

An old cliché admonishes, “Bad things always come in threes.” Whether it was thought of as a law of nature or merely coincidence, a rapid succession of events in North Africa during the summer of 1942 seemed to confirm this widely held notion among the officers and men of the British Eighth Army.

The first event was the Battle of Gazala (May 26-June 15), which witnessed a resurgent German-Italian Panzerarmee Afrika under Erwin Rommel tear through the fortified British Commonwealth defensive lines. That success forced the British—almost in rout—to flee east over the Libyan-Egyptian border. The second event was the surprisingly quick collapse in just two days (June 20-21) of the British fortress of Tobruk, which had the year before withstood an Axis siege of eight months. And with Tobruk’s fall came the capture of 32,000 Commonwealth troops and a promotion to field marshal bestowed on its conqueror, Rommel. The third event was Eighth Army’s bungled defensive stand at Mersa Matruh, with the loss of a further 7,000 British prisoners of war, on June 26 and 27, which should have delayed if not stopped the enemy’s advance, resulting instead in another precipitate British retreat deeper into Egypt.

On June 25, just before the fiasco at Mesra Matruh, the commander of all British forces in the Middle East, General Sir Claude Auchinleck, took personal charge of Eighth Army’s operations. From the fall of Tobruk to the moment the stampede of English units out of the Mersa Matruh defense locale toward the east began, Auchinleck’s objective was to keep Eighth Army together. Although it had suffered severe losses in men and material and was much disorganized, it was more bewildered than demoralized; its basic framework was still intact and was certainly capable of further efforts. Auchinleck correctly identified that the continued existence of Eighth Army, no matter how much territory was given up, made the present critical situation retrievable. Indeed, Auchinleck knew that considerable reinforcements were on their way to Suez. These included 300 American M4 Sherman tanks, 100 self-propelled artillery pieces, and a large number of U.S. Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers originally destined for China but rerouted to Palestine. Further, the British 8th Armored Division and the 44th and 51st Infantry Divisions were en route to Suez.

If the fight against the Panzerarmee could be maintained until at least some of these reinforcements reached Egypt, then defeat might be averted and a victory over a dangerously overstretched Axis army might be achieved. But this did not alter the fact that Eighth Army was at the time heading back to a last-ditch position with a determined enemy constantly nipping at its heels and trying to strike a mortal blow.

The El Alamein Line

The last-ditch position to which Auchinleck was shepherding his battered command was a point 300 miles east of the Libyan-Egyptian frontier—and less than 100 miles from the city of Alexandria and the vital Suez Canal—at a small railway station known as El Alamein. Already, several brushes had taken place in the desert inland of El Daba between small parties of British and Germans, all determined to make the “Alamein line” as quickly as possible. By June 30, the majority of the retreating Eighth Army had either reached or was close to entering the Alamein line. Among them were members of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps, who after hearing a BBC radio announcer report that Eighth Army had reached the El Alamein line, looked around at the empty desert, indistinguishable from the miles of sand to the east and west, and commented with curses and derision as only riflemen could. There was no line at Alamein on July 1, only a widely scattered series of defensive boxes in disrepair.

The name El Alamein came from the rail stop British engineers built there in the 1920s. While surveying the route of the pending track, the engineers planted two flags in the sand to mark the stop. Local Bedouin tribesmen then called the spot “el Alamein,” meaning “two flags.” In 1942, the place was an empty space except for the small group of railway buildings standing in the desert. North of the rail line near the coastal road rose a shoulder of rock, which formed a small line of hills sloping away to the salt marsh on the coast. To the south the ground was made up of desert covered with clumps of camel thorn. However, the desert surface alternated from a rocky limestone bed with a thin covering of sand to areas of deep soft sand. Roughly 10 miles south of the tracks was Miteiriya Ridge, which stretched in a wide arc across the desert landscape.

Ten miles farther to the south running west to east was a low hump of rock known as Ruweisat Ridge. About 15 miles southeast of the station and seven miles to the east of Ruweisat Ridge sat Alam el Halfa Ridge. All three ridges were made of hard rock barely covered with loose sand, which made the construction of field defenses on them very difficult. In addition to the ridges there were a number of mounds (tels) and various sized shallow depressions called deirs. A little more to the south the ground changed in to a much rougher, rockier terrain culminating in a series of high hills that overlooked the cliffs at the edge of the impassable Qattara Depression.

Before the war the Alamein line, which stretched for 38 miles, had been recognized as a possible site for a position from which to defend the Nile River Delta. As a result, in early 1941 the British had laid out a defense line consisting of three fortified boxes across the Alamein chokepoint. The most important box was constructed as a 15-mile semicircle around the rail center designed to hold an infantry division. Halfway down the desert another box was laid out at Bab el Qattara. Farther south the Naqb Abu Dweiss box commanded the approaches leading to the depression itself. The boxes were 15 miles apart and, therefore, were out of mutual supporting distance. As a result, they could never be held independently.

Improvising a Defense

The assumption in 1941 was that a strong armored force would be employed to maneuver between the boxes to assure their successful defense. But in July of the following year the battered Eighth Army, with only 137 functioning tanks at El Alamein, did not possess enough armored fighting vehicles to protect the boxes. Further, after the November 1941 counteroffensive to relieve Tobruk (Operation Crusader) was initiated, the buildup of the El Alamein position was ignored. With little more than some barbed wire strung and a few mines laid to protect them, the boxes that constituted the Alamein line were really nothing more than a line on a map.

As the fragmented Eighth Army fell back to El Alamein in July 1942, Auchinleck scrambled to devise a way to defend it. His solution was based on the tactic that part of the army would hold positions to channel and disorganize any enemy advance; the rest would remain mobile to strike the foe from flank and rear. Auchinleck ordered his infantry divisions to form their maneuver elements into artillery battle groups (or brigade groups) whose activities were to be personally supervised by their division commanders. Corps leaders were to make sure that maximum forces were concentrated at the decisive points, even if those points were outside their assigned sectors.

Regardless of Auchinleck’s resolve to stop the Italian-German army at El Alamein, he realized that he might not be able to do so. If he could not, Auchinleck intended to fight step by step through Egypt, making stands at defensive positions that had been set up covering the western approaches to Alexandria, the Nile Delta, and Cairo. As a last resort, Auchinleck might hold the Suez Canal with part of his mobile force while the remainder withdrew along the Nile River.

In the meantime, as the plans for the worse case scenarios took shape, the British desperately tried to build up the strength of the El Alamein position in the face of the onrushing Panzerarmee. The 1st South African Infantry Division, after retiring from the Gazala line, had been sent to the El Alamein position and spent two weeks improving the defenses of the Alamein box by drilling out new sites, roofing in existing ones, laying down thousands of yards of barbed wire, and burying thousands of mines. The South Africans were also ordered to send out two mobile columns, that is, battle groups (the Army chiefs favored a composite force made up of an infantry brigade supported by two batteries of artillery) to watch the desert to the west and south of the box.

Auchinleck was determined that no troops should be left to be encircled in the static positions being beefed up on the El Alamein line. As a result of this understandable mind-set, only one infantry brigade of the South African division would be available to hold the Alamein box, although it was backed up by four artillery regiments. This assemblage of artillery was a step in the right direction since it signaled that the guns of the Eighth Army, about 500 pieces of all calibers, were finally being concentrated to deliver effective massive support fire.

Meanwhile, the remnants of the 50th Infantry Division were formed into three columns and deployed to cover the gap between El Alamein and Deir el Shein, with the 18th Indian Infantry Brigade placed in the latter box. Ten miles farther south, the 6th New Zealand Infantry Brigade, 2nd New Zealand Infantry Division, was deployed in the Bab el Qattara box, while the 4th and 5th New Zealand Infantry Brigades underwent reorganization. In the far south, the 9th Indian Infantry Brigade held the box at Naqb Abu Dweiss, but was nearly isolated from the rest of the line due to a lack of transport.

“Our Only Offensive Weapon is Our Air Striking Force”

As late as midday on June 30, although most of the Eighth Army’s infantry formations (a combined strength of around 30,000 combat troops) had settled into the El Alamein front, all its armor forces had yet to arrive. The surviving elements of the 1st and 7th Armored Divisions, along with the 2nd, 4th, and 22nd Armored Brigades, were still 50 miles to the west near Fuka and motoring toward El Alamein with only the slightest notion of where they were to be placed. Until the tanks could reach their allotted positions to support their friendly infantry, the El Alamein line was simply too thin to resist Rommel’s armored spearheads. Further complicating the situation was the fact that the army had lost thousands of vital tons of ammunition, fuel, food, engineer supplies, and transport, which would be needed to defend the El Alamein position. Almost all of the loss was from supply bases originally sited at or near Tobruk and captured by the Germans when that bastion fell.

As the Eighth Army was reeling from its defeats at Gazala, Tobruk, and Mersa Matruh and heading farther into Egypt, its comrades of the Desert Air Force, under Air Vice Marshal Arthur Coningham, provided an offensive punch, the only one the British possessed at the time in the Western Desert. According to Maj. Gen. Eric Dorman-Smith, Auchinleck’s chief of staff, in the face of the Panzerarmee’s superiority in armored maneuver warfare, the Eighth Army had to buy time to rebuild its tank force through a defense of the Red Sea ports. Dorman-Smith went on to say that as a result of the weakness of the army’s armored formations, “Our only offensive weapon is our air striking force … it alone enables us to retain any semblance of initiative.” In contrast to the noticeable lack of the presence of the Luftwaffe, the Desert Air Force dominated the skies over the Eighth Army as the ground forces moved back to El Alamein. The Australia-born Coningham committed every available plane he had to the defense of the army as it retreated, hoping to disrupt the enemy’s advance as much as possible.

From June 23 to June 26, the fighters and bombers of the Desert Air Force made a maximum effort to slow down the oncoming Panzerarmee Afrika even as it leapfrogged to the rear itself. After June 25, a program of round-the-clock bombing was initiated, which continued for the rest of the Desert War. The result was that the Axis forces were compelled to move and bivouac dispersed even at night, thus slowing their movement and preventing a concentration of forces when attacking.

Rommel Outruns the Luftwaffe

Although slowed by exhaustion and the rain of aerial attacks on it during the last days of June 1942, the Panzerarmee forged ahead after the action at Mersa Matruh. Rommel knew speed was critical if he was to throw the enemy out of his last defensive position. His divisions were drawing on their last reserves of morale and physical strength as they moved forward. A lack of transport to deliver replacements, ammunition, and fuel to the units, which had fought hard and suffered losses and traveled nonstop since May, resulted in seriously depleted combat formations. At the end of June total armored strength available to Rommel stood at 55 German and 70 Italian tanks. His artillery comprised 330 German and 200 Italian pieces. It was Rommel’s force of will that kept Panzerarmee’s weak spearheads driving forward.

Regarding air support, the Panzerarmee was at a distinct disadvantage. In pushing his command so far and fast Rommel had outrun the Luftwaffe’s ability to provide air cover. The Luftwaffe simply did not have the means to keep up with Rommel’s blistering pace. Also, its resources were stretched too thinly since it was not only tasked with aiding Rommel in his land campaign, but also committed to the reduction of Malta, which was deemed essential to alleviating the horrible supply shortages the Panzerarmee continued to endure. The Luftwaffe’s efforts to support Rommel during the Battles of Gazala and Tobruk were massive but could not be sustained. As a result, when the Panzerarmee crossed into Egypt on June 23, friendly air support evaporated. If Eighth Army had been subjected to continuous enemy air attack during its retreat after the loss of Tobruk, the defeat would have turned into a catastrophe.

The First Battle of El Alamein

Even with all the problems facing the Panzerarmee, as it closed in on El Alamein at the end of June, Rommel felt optimistic about his prospects of breaking British resistance and capturing the Nile Delta. At the start of the month, Rommel initiated an assault that spawned a series of nearly continuous and heavy battles over the next 30 days on El Alamein line.

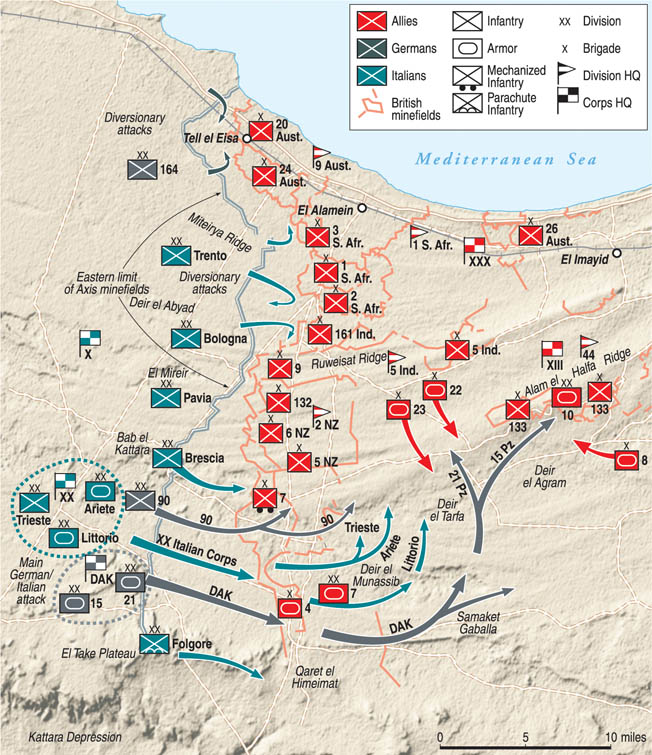

The contests began with a typical Rommel operation, which was a repeat of his successful stroke at Mersa Matruh. His intent was to penetrate between the Alamein box and Deir el Abyad with the object of cutting the coastal road, then make a sweep south with his armor to eliminate the Qattara box. But this thrust was blocked by British XXX Corps (composed of mostly infantry) in the north, while XIII Corps (mainly British armor) tried to attack the Axis southern flank. This encounter, which commenced on July 1, led to three days of battle during which the Panzerarmee assaulted the British-held Ruweisat Ridge twice but failed to gain all of it. Meanwhile, XXX Corps continued to bar the way to the coastal road while XIII Corps maneuvered to outflank the enemy by moving to the north and northwest, but without success. Stymied in his efforts and under pressure from a reinforced Eighth Army, Rommel suspended his attacks and dug in on July 4.

The British now went on the offensive. On July 10, they attacked near the coast at Tel el Eisa hoping to advance to Deir el Shein and the German-held airfields at Ed Daba. Their efforts were met by strong German counterattacks on July 12. Between July 14 and 16, Auchinleck struck the Italians holding the Axis center on Ruweisat Ridge and gained a foothold on that height. The fight for the slope continued on July 21-23. To relieve the pressure on their ally on Ruweisat Ridge, the Germans counterattacked but were repulsed. On July 22, the British captured Tel el Eisa. Initiating Operation Manhood on July 27, the armor of XIII Corps captured and consolidated its hold on Tel el Eisa and occupied the Miteirya Ridge; however, the latter was lost to a German counterattack. On July 31, Auchinleck felt compelled to suspend further offensive moves and pause to reinforce, retrain, and reorganize his battered army.

The fighting in July, which is known as the First Battle of El Alamein, had been costly to both sides and was in many respects disappointing to each, but it brought the Axis advance to a standstill and ended the run of British battlefield disasters.

As for the Panzerarmee, it had fought the July battles against an enemy constantly absorbing replacements of men and material, while it barely received a trickle of those commodities. As exhausted as their opponents, Rommel’s forces not only held their own but also delivered sharp counterpunches that stopped the British in their tracks. Most importantly, the German field marshal had preserved his army and prevented its destruction.

While the exact number of those killed and wounded in the Panzerarmee during the July fighting is unknown, at least 7,000 prisoners (5,000 Italian and 2,000 German) were captured by the British. During this period the Eighth Army suffered 13,000 casualties. Even as combat took place, the El Alamein line was being greatly strengthened in anticipation of the inevitable Axis offensive.

Reorganizing the Eighth Army

In preparation for the next blow Rommel was sure to deliver, Auchinleck acted on the premise that due to a paucity of seasoned German infantry an attack on the El Alamein line’s northern sector could be discounted. Accepting the views of his veteran armor corps commander, Lt. Gen. William H.E. “Strafer” Gott , the commander in chief expected Rommel to hook around Eighth Army’s southern flank and head for the Alam el Halfa Ridge. The possession of that height provided excellent observation and good terrain to the coastal road. Alam el Halfa, as Gott strenuously pointed out, was not only vital to any German advance down the coast to Alexandria, but also vital to the Eighth Army for holding its present positions on the El Alamein line.

Hoping to achieve better cooperation between his infantry and armor, Auchinleck proposed to defend his position by abolishing the distinction between armored and infantry divisions, creating in their place mobile divisions composed of one armored and two infantry brigades.

Auchinleck also planned a new Eighth Army offensive with the main blow coming from the north. In the meantime, he ordered that the El Alamein line be fortified in depth and in breadth. To that end, in the northern zone two defensive lines were built. These were held by the infantry of XXX Corps. To hold the important Alam el Halfa Ridge, Gott assigned its defense to the reliable 2nd New Zealand Infantry Division. He replaced the two brigade boxes, which could not mutually support one another, with the entire New Zealand Division backed up by massive artillery. Alam el Halfa thus became the main bulwark protecting the west and southern faces of the El Alamein line. Just to the south and west of that slope the bulk of the army’s armor was posted to intercept the expected Axis armored turning movement as it rounded Eighth Army’s southern flank. Auchinleck’s scheme was a novel one, but he would not be around to see if his new ideas for attack and defense worked.

Even before the July fighting on the El Alamein line finished, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had urged Auchinleck to undertake a general offensive to clear the Germans and Italians from North Africa. Auchinleck responded that such an effort was not possible before September 1942, if even then. A perplexed Churchill decided to visit Egypt in early August to determine future strategy for the Middle East.

Bernard Montgomery Takes Command

It was not long after his arrival in Cairo that the British leader determined to replace Auchinleck with someone he felt would be more offensive minded. His choice was Gott, a veteran of the Desert War since its beginning in 1940, and commander of Eighth Army’s main armor component, the XIII Corps. Unfortunately, on August 7, 1942, Gott was killed when the bomber he was traveling in was shot down by two German fighter planes. Churchill then appointed his second choice, Lt. Gen. Bernard Montgomery, to take over the Eighth Army.

As soon as the 55-year-old veteran of World War I, an active participant in World War II since 1939, reached his new command, Montgomery started to remake the Eighth Army in his own image. His first address to his new staff made a tremendous impact. The defense of Egypt lay at El Alamein, Montgomery said, and if the Eighth Army would not stay there alive it would stay there dead. There would be no more backward looks, and if Rommel chose to attack so much the better.

Montgomery further declared that under him the army would fight differently. No more brigade groups; divisions would fight as entire divisions. No more isolated defensive boxes; all defensive positions would be integrated and mutually supporting. What he never admitted was that the basic outline for the British conduct of the Battle of Alam el Halfa followed the concept of his much underestimated predecessor, Claude Auchinleck.

The entire army was impressed by its new chief’s can-do attitude. Churchill also was impressed. On August 21, Churchill wrote: “A complete change in atmosphere [in Eighth Army] has taken place … the highest alacrity and activity prevails.” The prime minister might also have noticed the new Eighth Army commander’s trademark: meticulous planning and preparation.

Rommel Requires a Rapid Victory

As Eighth Army recovered from the July 1942 battles, it not only greatly improved the defensive capabilities of the El Alamein line but also received a vast influx of men and material. From July to August the army received 730 tanks, 820 artillery pieces of all kinds, more than 15,000 vehicles, and thousands of tons of supplies. Eighth Army’s manpower in August rose to around 150,000 men.

On August 30, 1942, Rommel wrote to his wife: “There are such big things at stake. If our blow succeeds, it might go some ways in deciding the whole course of the war. If it fails, I hope at least to give the enemy a pretty thorough beating.” The field marshal, after being stymied during the July battles, had decided to launch his army in one last attempt to reach the Nile Delta. He knew it would be a now or never proposition.

During August 1942 the Panzerarmee existed in a quartermaster’s nightmare with the troops living from hand to mouth on captured food, fuel, and ammunition. Supplies for the army shipped from Italy were regularly sunk by the British Navy and Air Force, and whatever got through to Benghazi or Tobruk was eaten up by the long haul to the front. Of the 100,000 tons of supplies the Panzerarmee required each month, only a fraction ever got to the troops in Egypt. With this in mind, Rommel knew he had to attack before the British received more men and tanks and before the enemy could weave a shield of defensive minefields, which would be too dense to permit a rapid breakthrough of their lines.

Discounting any idea of assailing the heavily defended northern sector of the British line, Rommel opted to strike in the south, using his tanks and mobile forces to encircle and destroy Eighth Army in a repeat of the Gazala battle. His strike force would not be concentrated until the eve of the attack, and to maintain the element of surprise there would be no artillery or air preparation. Limited infantry attacks would be mounted along the entire front to pin down and confuse his opponent. Once his armored and motorized elements were assembled south of Deir el Qattara, they would push through the British minefields, which recent Axis reconnaissance assured would be easy to clear, drive east, then turn north for the coast road. The plan was to encircle the opposition and cut him off from his supplies.

The force Rommel had by late August consisted of 84,000 German and 44,000 Italian troops and 234 German and 281 Italian tanks. But his supply of transport, fuel, and ammunition was barely sufficient to sustain anything but a rapid victory.

The Afrika Korps’ Offensive Begins

On the night of August 30, 1942, Rommel began his offensive. The tanks of the Afrika Korps (15th and 21st Panzer Divisions), the 90th Light Motorized Infantry Division, and the Italian armored divisions Ariete and Littorio (containing barely half their full 16,000-man complement) assembled on the southern flank of the German line around the El Taqua plateau. The plan called for this entire force to pass through the British minefields north of Qaret el Himeimat and then drive east. Rommel’s tanks were to be protected on the left flank by reconnaissance battalions and on the right by Italian armor.

Near the Munassib Depression behind Eighth Army’s front line, the 90th Light Division would act as a hinge between the static Axis forces to the north and the advancing Afrika Korps. The whole force was then to wheel north, bypassing Alam el Halfa and heading for the British rear at the eastern end of Ruweisat Ridge. Meanwhile, it was hoped that Eighth Army would be distracted by the German 164th Light Motorized Infantry Division and the Italian X and XXI Infantry Corps, which were to mount raids all along the enemy’s front. Unfortunately for Rommel, air superiority was with the British. It was a bold plan requiring speed, surprise, and enough fuel to make it work.

As darkness descended over the desert, the Africa Korps approached the British minefields. It appeared that the attackers had achieved surprise, but then around midnight they clashed with the 7th Motor Brigade, British 7th Armored Division. Soon the Desert Air Force began dropping bombs on the Afrika Korps. Bunched up to pass through the British minefields, a number of German tanks, infantry carriers, and supply trucks were destroyed.

As the Germans were hung up in the minefield under air assault, they were met by fierce resistance from the three battalions of the 7th Motor Brigade defending 13 miles of the British front. After four hours of fending off the enemy, the Motor Brigade, covered by the British 4th Light Armored Brigade, was forced back by overwhelming German pressure. Rommel’s hope to traverse the 42 miles to the east and then turn toward the coastal road during the moonlit night of August 31 was frustrated.

Rommel’s Great Mistake

Seriously delayed by the stout defense by the 7th Motor Brigade, mines, and air raids, it was not until 5 am that German engineers were able to clear gaps in the British minefields and allow the panzers to push forward. More misfortune struck the Afrika Korps when an air attack hit its headquarters, wounding the corps commander, General Walther Nehring. Colonel Fritz Bayerlein, Rommel’s chief of staff, took charge of the corps. Twenty minutes later, Maj. Gen. Georg von Bismarck, commander of the 21st Panzer Division, was killed by mortar fire. The command and control of the Afrika Korps was badly disrupted at a critical moment.

Farther north, the actions conducted by the Italian engineers and German paratroopers designed to tie down the British forces in that sector were generally a failure. One exception was the advance of the Ramcke Paratrooper Brigade against a British position held by the 9th Indian Infantry Brigade, 5th Indian Infantry Division, on Ruweisat Ridge, although the Germans were eventually forced to retreat.

By 8 am, the 21st and 15th Panzer Divisions found themselves about three miles east of the enemy minefields and preparing to drive eastward. After arriving at Africa Korps headquarters that morning, Rommel realized that the minefields had not only caused time delays and casualties, but also consumed large amounts of fuel he could not replace. Therefore, he modified his original battle plan. Due to insufficient fuel to make the planned wide sweep to the east, he directed his panzers to turn immediately to the north after Bayerlein persuaded him to continue the attack.

The objective now for the Afrika Korps was Point 102 situated on the Alam el Halfa Ridge, with the Italian XX Corps ordered to take Alam Bueid. Because the Ariete and Trieste Divisions were held up in the British minefields, they could not attack their objective until that evening thus depriving the German tanks of support when the latter attacked Alam el Halfa. More valuable time was lost when, in attempting to implement the new plan, the Littorio Division trespassed onto 21st Panzer’s route of march. It took more than an hour to untangle the two divisions and proceed toward Alam el Halfa.

As it turned out, Rommel’s decision was the worst he could have made. His new scheme was going to pit his tanks against the 22nd Armored Brigade and 44th Infantry Division, both entrenched on Alam Halfa and waiting for Rommel’s armor.

Fighting Through a Sandstorm

As the afternoon of August 31 wore on, the Axis turning movement continued. Ahead of it the 7th Motor Brigade, supported by 22nd and 4th Light Armored Brigades (also part of 7th Armored Division), fell back to the Ragil Depression. The 7th Armored Division had done its job, seriously slowing Rommel’s tanks. The 23rd Armored Brigade was attached to XIII Corps and moved south to cover the gap between the New Zealand defensive position and the 22nd Armored Brigade at Point 102 on Alam el Halfa.

In the air, the Desert Air Force was now restricted in its efforts due to a sandstorm. On the Axis side, sorties by 240 fighters and 70 dive bombers of the Luftwaffe and Italian Air Force had little effect on the ground battle.

About 1 pm, in a raging sandstorm that was blowing in the face of the British defenders and reduced visibility to 100 yards, the 21st Panzer Division, with 120 tanks in three waves, turned directly for Point 102. Ahead of the advancing panzers stood the antitank guns of the British 1st Rifle Brigade, supported by the Crusader tanks of the 22nd Armored Brigade’s 4th County of London Yeomanry Tank Regiment. When the panzers were just 300 yards from them, the Rifle Brigade’s 6-pounder antitank guns opened up. Along with accurate artillery fire, the antitank screen destroyed 19 German tanks. Unsupported (the 15th Panzer Division during the attack had to curtail its movements due to lack of fuel), the 21st Panzer Division’s strike was more hesitant than usual, and it stopped its attack at 4 pm, drawing off toward the Ragil Depression at nightfall. The division claimed it had eliminated 12 enemy tanks and six antitank guns in this action. In the meantime, Montgomery ordered 23rd Armored Brigade with its Valentine tanks and the 2nd South African Infantry Brigade, 1st South African Infantry Division to take station just north of Alam el Halfa Ridge as a ready reserve.

That evening, Bayerlein suggested to Rommel that both panzer divisions break contact with the British and attack Point 102 from the flank. It was a good idea, but lack of fuel made it impractical. British airpower returned hitting, both German armor and supply transport congregating at the Ragil Depression.

To the north, a small force of Australian infantry supported by a squadron of tanks mounted an attack near Tel el Eisa as a diversion to disrupt the main Axis attack in the south. The assault was quickly counterattacked by elements of the German 164th Light Motorized Infantry Division, forcing the attackers to retreat.

Montgomery Regroups

With barely any fuel reaching them on September 1, the tanks of the Afrika Korps could do little that day. While 21st Panzer settled into a defensive posture due to dry fuel tanks, the 15th Panzer Division was ordered to renew the attack on Alam el Halfa. Its probing of the ridge was stopped cold by the efforts of the 22nd and 8th Armored Brigades. The 8th lost 13 M3 Grant tanks to a German antitank screen while destroying eight Panzer III tanks and one Panzer IV. By that night, the Afrika Korps was out of fuel and confronted by all the tanks of the Eighth Army, which had gathered around Alam el Halfa Ridge.

Throughout the day, the British massed seven field artillery regiments near the New Zealand positions and pummeled the static German and Italian armored units leaguered to the south. The Desert Air Force flew 125 sorties against the same enemy targets.

Montgomery used that afternoon to leisurely “regroup so as to form reserves and make troops available for the closing of the gap between the New Zealanders and Qaret Himeimat and seizing the initiative.” These moves were not completed until September 2, due to a lack of urgency on the part of Montgomery and a lack of transport vehicles to move the troops.

Operation Beresford

Throughout the morning of September 2, the Germans and Italians remained camped waiting for an enemy counterattack that never came. At 10 am, new orders were received by the German mobile forces. Rommel had decided to break off the offensive due to the severity of enemy air attacks and the lack of fuel. His subordinates were shocked at the decision and felt they could still defeat the enemy if given the needed fuel in a timely manner. Battle groups from each panzer division were to be formed to cover the retreat.

The Littorio Division was ordered to hold its position while the German tanks pulled back. After that occurred, the Littorio, Trieste, and 90th Light Divisions also withdrew. The retreat started the next day, and by that evening the strike force of the Afrika Korps was ensconced just west of Deir el Munassib. That point, as well as Qaret el Himeimat, which afforded good observation of the surrounding area, were retained by the Axis and incorporated in their new defense line. It was, in effect, a consolation prize for the sacrifice they made to lever the enemy from the El Alamein line.

Realizing that the enemy was withdrawing, Montgomery, rather late that day, directed his XIII Corps to pursue and harry the beaten enemy and close the gap the Germans had opened in the British lines at the commencement of their attack on August 30. With only small units of the 7th Armored Division ordered to carry out Montgomery’s belated instructions, the Axis withdrawal was virtually unhindered. The only real damage to the withdrawing enemy was caused by the Desert Air Force, which during 176 sorties dropped 112 tons of bombs.

[text_ad]

Instead of a vigorous pursuit, Montgomery ordered Operation Beresford, an infantry attack designed to “reestablish the minefield to the south of the New Zealanders’ position.” It was to be carried out by the 132nd Infantry Brigade, 44th Infantry Division, supported by the 5th and 6th New Zealand Brigades covering the 132nd on each flank. The attack fell on the positions held by the Italian 27th Brescia Infantry Division, X Infantry Corps.

The operation was a dismal failure, costing the 132nd Infantry Brigade 697 men and the 5th New Zealand Brigade 275 soldiers. One battalion of the Brescia Division lost heavily during an engagement with the 5th New Zealand. Soon after the attack began, the 6th New Zealand Brigade joined the action against the 101st Trieste Motorized Infantry Division and the 90th Light Division. One bright spot in the whole sordid tale of Operation Beresford was that it showed how well the British artillery had learned to play its role in supporting infantry and armor. Its timely intervention prevented the destruction of the 5th New Zealand Brigade.

The End of the “Six Days’ Race”

With the failure of Operation Beresford, the Eighth Army’s attempts to interfere with the Panzerarmee’s withdrawal ended. Patrols from the 7th Armored Division and the 8th and 22nd Armored Brigades harassed the Axis rear guards. By September 5, the fuel situation for Rommel’s army had improved somewhat, allowing it to operate for the next seven days. On the 6th, the Battle of Alam el Halfa ended.

The “Six Days’ Race,” as the Axis troops dubbed the Battle of Alam el Halfa, was over. It was Rommel who had received a beating. The cost to the Eighth Army amounted to 1,750 men killed, wounded, or captured. The British lost 67 tanks, 10 pieces of artillery, and 15 antitank guns. The Panzerarmee sustained 1,859 German troops killed, wounded, and missing, as well as 49 German tanks, 55 pieces of artillery, and 300 trucks destroyed. The Italians lost 1,051 men, 22 guns, 11 tanks, and 97 other vehicles.

Both Rommel and Montgomery made mistakes during the struggle. The latter was fortunate that his rigid static defense strategy was not compromised. His foe had run out of fuel and could not maneuver at will. The former was lucky that he faced an opponent who, due to his inherent caution, did not make an all-out attempt to destroy his immobile strike force as it sat in front of Alam el Halfa Ridge. Rommel’s good fortune continued when Montgomery did not pursue him as his command was retreating and hampered by a lack of fuel.

In the final analysis, Rommel seems to have learned little from the battle as far as the interdependencies of his logistical situation and how those considerations hampered his operations.

As for the British, even if the Eighth Army had not exploited its advantages during the battle, it still gained a conclusive victory over a previously unbeaten antagonist. The British victory at Alam el Halfa caused the morale in the army to soar and gave the troops every confidence in Montgomery’s leadership. The victory also assured the soldiers that the next time they met the Panzerarmee in combat, the British would be doing the attacking, with every chance of a successful outcome. And so it was.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments