By Glenn Barnett and André Bernole

Roger Sauvage was born in Paris in 1917 to a white Parisian woman and a black soldier from Martinique. His father had come to France with his island regiment to fight for France in World War I. Around the time of his son’s birth he was killed at the “Seconde bataille de Chemin des Dames” (Second Battle of the Aisne.)

Roger was raised by his mother in the Ménilmontant District of Paris and grew up every inch a Frenchman. When he was 16 years old, he read a biography of Georges Guynemer, one of France’s top flying Aces in the Great War with 53 victories. From that point on Roger wanted to fly. He was then attending high school but soon dropped out and enrolled in a flight school where he studied mathematics and mechanics while flying gliders or small planes whenever he could.

Some of his early expenses were paid by the Aviation Populaire, a government organization that selected and sponsored young men to become pilots at a time when the French budget allocated little money for the purpose. Germany, meanwhile, was training thousands of pilots.

In the peacetime of the 1930s, the small French Air Force took only the most qualified pilots. In 1937, Sauvage stood for the entrance exams for the French Air Force, the Armee de l’Air. He passed and was selected as a reconnaissance pilot with the rank of sergeant.

Sauvage was assigned to the 553rd Observation Squadron based in Strasbourg. He flew missions in a Mureaux 115 aircraft and photographed fortifications along the Siegfried Line. But Roger wanted to be a fighter pilot.

In April 1939, he got his wish. He was transferred to Fighter quadron (Groupe de Chasse or GC) 1/5 based at Reims, home to 300 pilots.

The 1/5 squadron was equipped with a twin-engine fighter called the Potez 631. Originally designed as a light bomber, the Potez, an all-metal monoplane, proved to have excellent handling capabilities and was converted to the fighter role. But when the war began the Potez proved slower than some of the German bombers and less maneuverable than the Messerschmitt Me-109 fighter.

By September the war was on. Roger flew his first wartime mission on September 25, 1939, a patrol along the border. The coming winter of 1939-40 was brutally cold and drastically cut back on flying.

On May 13, 1940, during the confused early days of the Battle of France, a group of four Canadian RAF pilots patrolling in their Hurricane fighters mistook Sauvage’s Potez 631 for a twin-engine German Messerschmitt Me-110 and shot him down. He was not hurt and was able to open his canopy and deploy his parachute. Unfortunately, it was a hard landing and he was hospitalized briefly after lapsing into a coma.

He was soon back in the air, and on May 18, he surprised a Heinkel He-111 bomber from above with a quick burst of his 20mm cannon, causing it to make a forced landing. Roger landed next to the downed Germans and took them prisoner. He also “liberated” a Leica camera from them and kept it throughout the war. It was his first aerial victory. On June 16, he downed a Dornier Do-17 light bomber. Soon after, the Battle of France ended with a humiliating surrender. Roger had flown 19 missions with two victories during the brief war.

After the fall of France, Sauvage considered escaping to Gibraltar and then to England, but his squadron was grounded by the new Vichy government who suspected that some of the pilots might have Gaullist beliefs that France should fight on. He was transferred to another squadron and sent first to Morocco and then Algeria where, for over a year, he was assigned to a lonely air base at Aïn Sefra in the desert with little chance to fly except in trainers and gliders.

It wasn’t until the Allies had occupied all of North Africa that his fortunes changed. In September 1943, he and two fellow pilots were summoned to Algiers to meet with Free French recruiters including his longtime friend, Ukrainian born and Russian speaking Constantin Feldzer and Jacques Casaneuve, who offered the Gaullist minded pilots the opportunity to resume the fight against Germany.

Sauvage was given the choice of flying for the RAF or going to Russia, where he could join the Normandie squadron (GC3) already famous for its role in the Battle of Kursk in the skies over Orel.

The Normandie squadron was the brainchild of Charles de Gaulle, who wanted French forces represented on every front of the war. The first pilots arrived in the Soviet Union in November 1942, while the Battle of Stalingrad was still being fought.

After training in their new planes, the Russian built Yak-1 and Yak-9, the squadron was attached to the Soviet First Air Army and saw extensive action at Kursk and its aftermath. They acquitted themselves well but only five of the original 12 pilots survived. If it was to continue, the Normandie squadron needed new pilots.

Despite the terrible privations in Russia, Sauvage chose to fly with the Normandie squadron. He and the other volunteers soon found their way to Cairo, where they were met by an unrelenting round of parties and dinners in their honor.

From Cairo the group was flown to Tehran in Iran. There the small French expatriate community feasted them yet again. It was January 6, 1944, before Sauvage arrived at Normandie’s airfield in Tula, south of Moscow. Then the parties stopped. Russia was still suffering severe shortages of food that had led to widespread starvation the previous winter.

Sauvage was ready to fight immediately, but first he had to be trained in the unfamiliar Yak fighter. By now the early wood and canvas Yaks were being replaced by updated models with improved brakes and elevators and a larger gun. The Yak-9 was the squadron’s plane at the time.

With the arrival of the new pilots the squadron was organized into three escadrilles or wings. Sauvage’s first flight proved disorienting. After reaching an altitude of 2,000 meters he looked down on a vast sea of snow with no familiar reference points, only white. Once he located the Moscow-Tula rail lines he felt better, oriented himself, and landed successfully. Individual and group training went on all winter, weather permitting.

Sauvage and Marcel Albert, one of the surviving original pilots of the squadron, had been friends since their earliest days of flying. The popular veteran chose Sauvage to be his wingman and taught Sauvage valuable lessons. For instance, Roger learned to keep his head permanently on a “ball bearing” with his eyes constantly sweeping the skies for signs of the enemy.

In Russia, Roger stood out not only for the color of his skin but also because of his height, over six feet. This was unusual for a fighter pilot, especially since cockpits were always short on space.

The Soviets were planning an offensive in May. Until then there was little to do but practice flying and firing skills, play cards, smoke, drink vodka and, if possible, meet local women. During his time at Tula, Sauvage befriended a local female doctor named Irma and frequently stayed with her at night. During his stays in town, Sauvage did experience some prejudice from the locals, but he believed this was not because he was black but because he was a foreigner. One of his nicknames in the squadron was “le Nègre,” which in French was not then a derisive term.

Meeting Russian women was important to the Frenchmen even though they knew that some of them were working for the NKVD (forerunner of the KGB). One of the pilots would remember after the war: “We were living like animals, cold, dirty, hungry, and we were all becoming animals. These girls allowed us to be normal humans again; clean, shaved, dressed, with normal food. We owed a lot to them.”

By now so many new pilots were joining the squadron that they were able to establish a fourth escadrille, which allowed them to refer to themselves as a regiment rather than a squadron. Each escadrille was given the name of a French city in Normandy: Rouen, Le Havre, Cherbourg, and Caen.

In May, the Russian spring offensive left Tula in the rear, and the flyers, Russian and French, were moved to advance bases to the west. Accommodations were poor. The veterans were used to this, but Sauvage and the 13 new pilots, nicknamed “Rayaks” for their former airfield in Lebanon, who had joined with him found themselves housed in a leaky thatch-roofed hut with one side open to the elements. The logs of the surviving walls were chinked with dirt and straw which housed armies of lice, bed bugs and other insects that made life miserable. In the wake of their retreat, the Germans were destroying almost every structure that had not already been razed three years earlier by the retreating Soviets. So, this type of accommodation was the norm for the pilots and their Russian mechanics.

Normandie pilots fought alongside Soviet airmen of the 18th Guards Fighter Air Regiment under the command of General Géorgui Zakharov, who treated his French guests with great respect, trust, and camaraderie. The flyers settled into an endless round of flying cover for Russian ground attack planes like the Pe-2 and the more famous Ilyushin Il-2 “Sturmovik.”

Normandie pilots typically flew in groups of four or six about 1,500 feet above the Soviet ground attack planes to protect them from German fighters. The Soviets had only one standing order for their fighter pilots; do not return with a full magazine. If the pilots were not able to engage enemy fighters, they were to seek out targets of opportunity on the ground for strafing.

In June news came of the Allied landings in Normandy, namesake of the squadron. There was great excitement among the French pilots. On that night General Zakharov and pilots of the 18th Guards Regiment came to the French encampment for a celebration that included singing, dancing, and the consumption of great quantities of wine and Vodka.

In the summer of 1944, there was a curious absence of the Luftwaffe in the skies over the Eastern Front. Most of the German fighters were trying desperately to stave off the British and American bombers that were ravaging the Fatherland. Only flak and accidents brought down the Soviet and French pilots. It was a frustrating time for the fighter pilots, especially Sauvage who yearned to go up against Germany’s best. Still, he had to fly his assigned missions. All were eager for action. Albert called the pilots “les impatients” (The Impatient ones).

At the end of July, the squadron participated in a campaign to cross the Niemen River, the border between Poland and East Prussia. Stalin was so pleased with the results that he ordered that all participating battle units to add the word ‘Niemen’ to their regimental names as an honorific. The French pilots proudly took to their new name ‘Normandie-Niemen’. In August Sauvage became a patrol leader.

After flying Yak-9s for most of the year, the pilots were issued an improved Yak-3 on August 18, 1944. With and engine-mounted twin Schwak 20mm cannon, the Yak-3 was more maneuverable, allowed the pilot better vision, and had a faster rate of climb. It was a natural dog fighter and the pilots relished that role.

The new plane did not come without problems. In a power dive the early Yak-3s tended to disintegrate, and two Normandie pilots lost their lives in this way. As a result, the pilots were warned not to fly faster than 750 km/hr. Another problem was that after about ¾ of an hour flying time the engine would develop a vapor lock and shut down. This happened to Sauvage several times as he frantically hand pumped the fuel to get his engine going again.

The commanding officer of the Soviet mechanics assigned to the French flyers was Serge Agavelian, who was a graduate of the best engineering school in the Soviet Union. He was able to make adjustments that solved the problem and it was soon fixed at the factory.

On August 24 (actually a day early), Soviet radio announced that the western allies had liberated Paris. That night the French pilots and their Soviet hosts partied like never before. General Zakharov ordered all the guns along his front to fire in celebration (at the German lines of course).

Within a month however morale sagged again. Sauvage was typical of the malaise. So fast had the westward advance occurred that supplies and mail lagged behind. Without ammunition and fuel, the advance stalled. Sauvage noted with sadness that mail, so vital for morale, had not been received for six weeks. Adding to the misery of the flyers was a devastating dysentery affecting everyone. The squadron’s French doctor, Igor Eichenbaum, had no medication on hand to fight it. Sauvage sometimes was up six times a night because of the distress. The disease plagued him for five months even in combat. Yet he still flew.

By September 18, the squadron moved to Antonovo in Lithuania. As the French pilots moved into “Catholic” territory they found a population more likely to understand some French and the pilots made the most of it. Sauvage met a woman named Paula, whom he wooed in the presence of her ever vigilant mother.

He had not scored a victory since the Battle of France despite countless hours in the skies over the fierce fighting below. When German planes did appear overhead, primitive Soviet radar failed to detect them until it was too late to intercept them.

In September 1944, it was announced that the veterans, the four surviving pilots who had been in Russia since late 1942 were scheduled to go home in October. But on October 12, General Zakharov told the squadron commander that a new and powerful Soviet offensive would begin soon. In eight days, he promised, they would reach Konigsberg and the Baltic. He asked the favor of the French veterans to stay and see it through. They all did.

This caused a mad scramble among the airmen as the veterans had given away most of their possessions to the remaining flyers. Pants, boots, jackets, and maps were hastily returned. Albert, however, could not get back a bottle of vodka which was already empty.

On October 14, Sauvage finally began to record victories. While flying over a German airfield with three other pilots, a flight of four German Focke Wulf Fw-190 fighters was spotted below. The French dived on them. Sauvage fired a burst at one of them. He saw parts of the wing fly off before the plane exploded in mid-air. It was his first victory since 1940. He later mused in his diary that sneaking up behind a plane to shoot it down seemed more like murder than fighting, but that was the way to win.

There was no time for celebration. His continually turning head noticed two enemy fighters on his tail. For several minutes he was in a dog fight, turning and sliding, with an experienced Me-109 pilot. Neither could best the other. Sauvage finally used his Yak’s superior climbing speed to get away.

On October 20, a powerful Soviet artillery barrage heralded the new offensive. Flying with a wing of six planes, Albert announced that there was a flight of Junkers JU-87 dive bombers below them to the left. Sauvage immediately dived on the Stukas. Unfortunately, his power dive was too fast. He barely pulled out in time to avoid crashing nose first into the ground. When he recovered from the dive, he found a Stuka headed straight for him. He fired several bursts until the Stuka plummeted to earth.

Then Sauvage found another Ju-87 fleeing toward German lines and banked in behind it. The tail gunner hit his Yak several times. But the Yak’s firepower was greater. He killed the gunner with two quick bursts. As he lined up for the kill, however, his guns failed to fire. Fortunately, Albert was right behind him. In one burst the Stuka exploded. Now over German lines both their planes were hit by flak. They turned sharply for home.

Back at base Sauvage was irate with his Soviet mechanic, telling him heatedly that his guns failed to fire in combat, denying him a victory. He blamed the Russian made 20mm Schwak cannon which occasionally misfired. But when the mechanic opened the ammunition storage box it was empty. In the heat of combat, Sauvage failed to notice that he had run out of shells.

The problem of misfiring was also solved by the squadron’s brilliant Russian head mechanic, Agavelian. He discovered that the tracer shells left a powder residue in the barrel of the gun, which eventually jammed it. He ordered that anti-tank shells replace the tracers. This was opposed to all official rules, but it worked. The guns stopped jamming.

One day, Sauvage flew four sorties by 6 p.m. and was exhausted. His knees were shaking, he had a headache and an intense abdominal pain. It was then that the commander asked him to make a fifth flight. Dutifully he went back in the air. It was the kind of brutal schedule kept by the Russian pilots. The French could do no less.

The next day seven new French pilots arrived as reinforcements. Sauvage remembered well that by the end of the war five of them would be dead.

French and Russian victories soared at this time as the quality and quantity of Russian planes improved and the Germans were forced to field barely trained pilots and suffered from shortages of fuel. The offensive went well at first, but as the weather chilled it stalled as rain and mud grounded planes and impeded infantry and vehicles.

Still, by October 23, the French squadron moved to a forward base at Ckierki in eastern Poland. The French and Russians felt the disappointment of a stalled offensive, but heavy rain turned the primitive airfield to mud, which froze at night and thawed back to mud during the day.

Despite the muddy fields, the squadron continued to fly. On the 24th, Sauvage flew in formation with five other planes on patrol over East Prussia. After an uneventful flight, the French pilots turned and headed for home only to find a wall of fog in front of them. As they ran low on fuel, they desperately searched for an opening in the thick gray that lay below them. At last a clear patch was discovered and the airfield came into view just in time.

For a week fog grounded all planes in the area. Sauvage and others spent the time at cards, reading detective novels, playing phonograph records or making hopeful plans for the future. It was a much needed break as many of the flyers were still weakened by the effects of dysentery.

Around this time the Soviets held a party to commemorate the October Revolution. Appetizers, biscuits, and vodka were plentiful. Sauvage noted that the Russian dignitaries, gratefully, did not engage in their usual Soviet propaganda speeches.

Morale picked up in November when it was learned that General Charles de Gaulle would be coming to Russia in December and would be visiting with the squadron. Sauvage noted how much the men were looking forward to his visit.

The offensive resumed on November 19, and by the 27th, the regiment moved again. This time to Gross-Kalveitchen in East Prussia. The Normandie Niemen pilots were the first unit of the Western Allies to occupy German soil. Whole towns were deserted as the German population fled westward in advance of the vengeful Soviets.

The French and Soviets had reached a different world, one of modern furniture and comfortable beds with real mattresses. There were cattle and poultry in plenty and a nearby hunting preserve belonging to Nazi bigwig Hermann Goering. His forests teemed with tame deer which fell to hungry Soviet riflemen. By now the weather worsened again, and the offensive was halted until spring.

During their mutual fight the Soviets greatly appreciated the contributions of the French regiment and began to pile on the honors. Normandie Niemen was awarded the Order of the Red Banner, while veteran pilots Marcel Albert, Ronald La Poype, and Marcel Lefèvre (posthumously) were honored with Hero of the Soviet Union. By war’s end another would be awarded to Jacques André.

The idle squadron occupied itself in preparation for de Gaulle’s visit. It was thought that he might visit them in East Prussia, so supplies were collected for a banquet and the common areas were spruced up in anticipation. But de Gaulle would not be coming. Instead, the flyers along with Russian officers would go to Moscow to meet him.

As the weather was bad, the journey to Moscow would begin over land. A convoy of aging Studebaker trucks set off in weather that reached 5 degrees Farenheit. At one stop they were housed in a military hospital where the pilots enjoyed the forgotten delight of a hot shower and fresh sheets that were changed for them. There they remained until the weather cleared enough for the five-hour flight to Moscow.

All along their route they were feted by grateful Soviet generals who wanted to show their appreciation for the Frenchmen who had stuck with them through thick and thin. This camaraderie was in stark contrast to British and American efforts to fight on Soviet soil, which ended in distrust and mutual reserve.

The pilots, their doctor and interpreters would be meeting with De Gaulle. Sauvage and the other pilots reached Moscow in early December. The pilots gathered in their best uniforms inside a great hall. Speeches were made by Soviet dignitaries and the French ambassador. Then the men stood in a line that was four rows deep to meet their hero, de Gaulle himself. Because Sauvage was the tallest of them all, he stood in the back row.

Sauvage would later write that he and his mates were thrilled as de Gaulle made his entrance. For these brave men, he embodied France. He seemed poised and confident as he pinned medals on the chests of the French heroes. After the formal ceremony the pilots gathered around de Gaulle, who, in casual conversation, answered questions and seemed to know every man.

Soon, however, the happiness of the visit with de Gaulle was replaced by the sadness of losing the original veterans of squadron. On December 19, they flew home to a liberated France. Sauvage would especially miss his friend Marcel Albert.

Now there was little to do but await the coming spring and the final push to victory. The men gathered nightly at a cocktail bar on Maxim-Gorki Street. To their surprise it was an American style bar with drinks costing 80 rubles. Sauvage began a winning streak at poker. He also learned the foxtrot and American style ‘swing’ dancing.

The fame of their uniforms made the pilots a hit with the locals, especially the women — and one in particular. Her name was Tamara. She was the wife of a Russian colonel who was away at the front. She and Sauvage spent the rest of December together, but on the 30th he had to return to base in East Prussia, another sad parting.

Operations resumed on January 12, 1945, as the skies cleared. There were 36 pilots now in the squadron. The Luftwaffe was back in the air trying desperately to stem the Soviet juggernaut.

By this time in the war, the Germans were using raw recruits with little flight time or training due to severe shortages of fuel. But mingled with these novices were experienced pilots, who had been fighting since the Spanish Civil War. Some had over 100 victories. The trick for the French and Soviet pilots was to avoid the pros and engage the less experienced.

Life was a little easier for the pilots now. Sauvage was issued a brand new Yak 3. The problems with the plane had been fixed. Finally, a well-fitting tarpaulin was provided to protect the engine from the -30 degrees Celsius (- 22 degrees F) weather. Before dawn, his mechanic could run glycol through the engine to warm it before startup. Steamrollers replaced the legions of shivering women who used to shovel snow from the run way.

For Sauvage, it was his most productive time. He was at last promoted to sous (second) lieutenant and immediately proved his worth. On the 16th, he led a flight of six planes guarding the Sturmoviks. Ahead of them they spotted a dozen German planes. The less experienced Germans formed a defensive circle, sometimes called a Lufbery circle, that allowed each plane to cover the one in front of it.

But when an inexperienced pilot panicked and broke the circle, Sauvage pounced on him. The German twisted and turned trying to evade him, but the Yak could turn inside him, and each time Sauvage crossed his opponent’s turn he sent a short burst of two or three shells, again and again. His shells slammed into the fuselage. All the while they were losing altitude until they were very near the ground. Suddenly the Fw-190 banked and hit the top of some trees and crashed — another victory for the Frenchman.

The Germans fled, and the faster Yaks chased them. Sauvage closed in on a second Fw-190 from about eight o’clock. He fired a burst, hitting the engine, and watched the pilot bail out before the plane crashed. In all, Sauvage’s wing claimed six victories for the loss of one of their own.

The next day, Sauvage was flying in a wing of eight planes when he spotted an Fw-190 strafing Soviet ground positions. He dived directly on the enemy despite flying into Soviet ground fire aimed at his opponent. He reached 800 km/h in the dive, and for three seconds he lined up the German plane in his sights and fired before frantically pulling on the stick to level out before hitting the ground.

He and his wingman rejoined the wing just before an overwhelming number of Fw-190s dove on them. Now the French formed a defensive circle to ward off attack. But one of the newer pilots broke away, only to be shot down by an enemy waiting for just such a mistake. His sacrifice allowed the others to escape in the confusion. That day the French lost two pilots, while a third had his elbow shattered by a 20mm shell.

On January 19, the weather was still frigid (-25 degrees C, and -40 degrees C at night). Roger wondered how the poor mechanics worked without gloves to maintain the planes. On that day Sauvage became involved in a huge dog fight with planes of both sides streaking around the sky shooting at each other. To escape from the enemy shells, he used every trick. He turned, nose-dived, climbed up again and always kept moving in another direction. All the while he looked for the “pigeon” who will sooner or later show in his sights. Eventually one did, and Sauvage shot him down.

Low on fuel and out of ammunition, Roger was attacked by an Fw-190. The two enemies contorted in the sky as Sauvage steadily worked his way east to safety. When the two flew over Soviet antiaircraft batteries, the German turned for home. Sauvage made an emergency landing, but by afternoon he was in the air again to score another victory.

In February, Roger added three more victories, including two Me-109s. On the 9th, he avoided being shot down by the most experienced German pilot he faced during the war. His score might have been higher if his mission was to seek out and fight enemy fighters, but the main job of the squadron was to protect the ground attack bombers while engaging in ground strafing and antiaircraft suppression. At this task the squadron excelled.

All the while, the Russians pushed relentlessly forward, and the French and Soviet flyers had to keep up, moving their bases constantly westward in order to support the advance. One temporary base was so close to the front that German artillery destroyed some planes on the ground. There would be at least nine moves forward from January until the war was over in May. Sauvage and his mates supported the First Air Army’s final battle at Konigsberg. His last victories came on March 27, when he shot down two Fw-190s.

When hostilities finally ended, Lieutenant Sauvage had 16 victories with at least one probable, and he was awarded seven major Soviet and French decorations. They were dearly earned. The Normandie Niemen Regiment claimed 273 enemy aircraft shot down and 37 probables. They lost 87 aircraft and 52 pilots in the service of France and their allies. Soviet Premier Josef Stalin was so pleased with the work of the squadron that he allowed each of the pilots to keep his aircraft and fly it home.

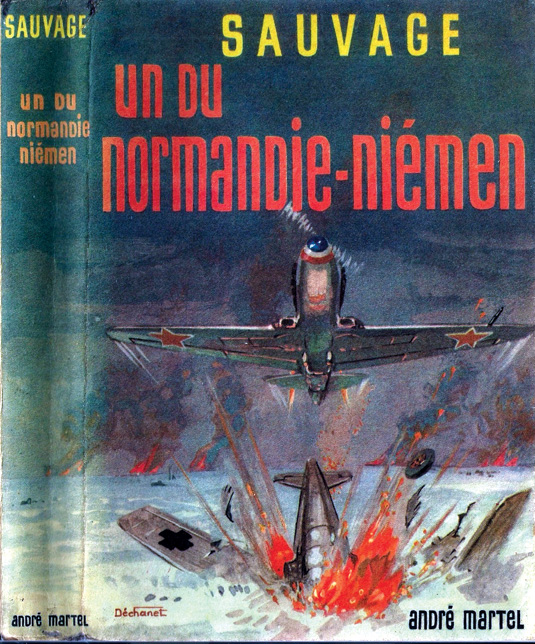

In June 1945, the entire squadron flying their Yak-3s landed in Paris to a hero’s welcome. Sauvage would stay in the Armee de l’Air after the war, serving with French occupation forces in Germany and rising to the rank of captain in 1950. In the same year, he published his memoir titled Un du Normandie-Niemen (One of the Normandie-Niemen). It was an immediate bestseller in France, enjoying three printings and a paperback edition. The authors are indebted to this work for much of this article.

Sauvage retired in 1969 and died in 1977. He is buried at a military cemetery in Nice.

The authors would like to thank Monsieurs Yves Donjon, the documentarian of the Normandie Niemen Association, and Lionel Sauvage for their support in preparing this article.

As a child in 1944, French historian André Bernole cheered allied forces streaming up the Rhone Valley after the invasion of Southern France. He interviewed the son of Roger Sauvage for this article.

Glenn Barnett has published over 30 articles about World War II. He has worked in aerospace on the Apache Helicopter, B-1B bomber and several space craft programs.

The first ground unit of the Western Allies to cross the German border was the US Army’s 85th Reconnaissance Squadron on 11 September 1944.

Then Aachen was taken in October 1944.

https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/the-battle-of-aachen-breaking-down-the-door-to-europe-in-wwii/

Otherwise, a great story.