By Victor Kamenir

The French Revolution of 1789, which began as a peaceful process of social and financial reform, rapidly descended into internal strife and violence. Virtually powerless, the French King Louis XVI and his Austrian-born queen Marie-Antoinette soon found themselves under what amounted to house arrest at the Tuileries Palace. Members of French aristocracy, faced with increasing hostility, surveillance, and physical violence, began to emigrate in large numbers to escape persecution, establishing armed émigré units in the immediate vicinity of French borders.

Concerned for Marie-Antoinette’s safety, the queen’s brother Leopold II, the Holy Roman Emperor and the King of Austria, issued a declaration on August 27, 1791, proclaiming his support for the deposed monarch and denouncing Revolutionary France. Joined by King of Prussia Frederick William II, Leopold carefully phrased the wording, stating he would go to war only if other major European powers went to war with France as well. In response to Louis XVI’s appeals for armed intervention and urged on by influential French émigrés, Austria and Prussia forged a military alliance in February 1792.

The National Assembly, the French governing body, interpreted the declaration and the military alliance as Austria intending to go to war. Viewing an external conflict as the solution to its internal problems, the French government preemptively declared war on Austria on April 20, 1792, unleashing the French Revolutionary Wars, which, in conjunction with the Napoleonic wars, were to shake Europe for nearly a quarter century.

Following the revolution, the French Royal Army was on the verge of collapse. Tens of thousands of aristocratic officers fled the county, discipline was shaken, pay was in arrears, and the supply system was in shambles. To supplement the disintegrating Royal Army, the French government in 1791 issued a call for national volunteers. Hundreds of thousands of enthusiastic Frenchmen responded to the call.

With so many officers gone, the losses had to be made good by promoting noncommissioned officers. Especially hard-hit by the officer flight was the cavalry, with its higher proportion of aristocratic officers. The artillery, the majority of whose officers were middle-class and received promotions based on merit, remained largely intact. In the volunteer battalions, promotion was by election. Popularity frequently substituted for competence, and a man with no military experience often found himself with the rank of general, and just as quickly a civilian again. Despite many newly minted officers being totally unsuited for their roles, a surprisingly large number of good men steadily rose to the top.

Eventually, under the amalgamé system, each white-coated battalion of the old Royal Army was combined with two battalions of blue-coated volunteers. The combined units were called demi-brigades, since the term regiment harked back to the Ancien Regime, which was the political and social system in France before the Revolution of 1789. The idea was for the old battalions to stiffen the resolve of the volunteers. Although the volunteers were willing and enthusiastic, they sorely lacked discipline and training.

Having disregarded the shape of the army and intent on exporting revolution abroad, the French government launched an invasion of the Austrian Netherlands in late April 1792, which it considered ready to embrace the revolutionary ideas. Senior officers who chose to stay and serve their country, such as Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, and Jean-Baptiste-Donatien de Vimeur, Comte de Rochambeau, urged caution, but were overruled by the increasingly radicalized National Assembly.

After repelling the French invasion, a combined Austrian-Prussian army, joined by French émigré formations, invaded France on July 30. Its objective was Paris. Facing the deadly threat, the French government sent out a rallying cry, “La Patrie en danger!” (The Fatherland is in danger!)

In addition, the National Assembly initiated a mass conscription. This levée en masse resulted in 1.2 million men under arms, formed into 14 armies engaged on all frontiers, as well as putting down internal royalist revolts, such as at Vendee and Toulon.

Despite initial setbacks, the French were able to check the professional Austrian and Prussian armies at the Battle of Valmy on September 20, 1792. The next day, the French monarchy was abolished, and four months later Louis XVI was guillotined in front of cheering Parisian crowds. In protest, England sent back the French ambassador, resulting in France declaring war on England, as well as on the Dutch Republic and Spain.

By the close of 1792, the French armies, while suffering several reverses, had overrun the Austrian Netherlands, as well as achieving successes in Italy and Alsace on the Rhine front. The campaigns of 1792 exposed weaknesses in the French army. The unsteady volunteers tended to flee and blame their generals for their defeats.

Moreover, the Committee of Public Safety, the executive arm of the National Assembly completely dominated by radical Jacobins led by Maximilian Robespierres, sent a number of representatives to each army to instill patriotic zeal in the troops and keep an eye on the generals. These representatives enjoyed the power of life and death, and many generals and senior officers were executed for offenses real or imagined. French generals had to fight while looking over their shoulders and a representative posed a more serious threat to a French officer than did enemy bullets. Officers were in greater danger from them and their own troops than from the enemy.

After two years of indecisive campaigns, the allied Austrian, Prussian, Dutch, and British armies controlled the Austrian Netherlands and the left bank of the Rhine River at the outset of 1794. The so-called war of maneuver, championed by Napoleon, was still several years away, and positional fighting was centered on French strongholds in northern France and the Austrian fortresses in the Austrian Netherlands.

The Austrian fortress of Charleroi, near the village of Charnoy, was built by the Spanish crown in the mid-17th century to protect its possessions in the Spanish Netherlands. Named after the Spanish King Charles II, the hexagonal fortress was situated at the bend in the Sambre River. Perched on the north bank of the river, Charleroi’s six bastions overlooked the gently sloping ground to the north, providing a dominating view toward west, east and south. By the time of the French Revolution, the Spanish Netherlands had evolved into the Austrian Netherlands, and the Austrian crown controlled Charleroi fortress.

The Austrian fortress of Charleroi, near the village of Charnoy, was built by the Spanish crown in the mid-17th century to protect its possessions in the Spanish Netherlands. Named after the Spanish King Charles II, the hexagonal fortress was situated at the bend in the Sambre River. Perched on the north bank of the river, Charleroi’s six bastions overlooked the gently sloping ground to the north, providing a dominating view toward west, east and south. By the time of the French Revolution, the Spanish Netherlands had evolved into the Austrian Netherlands, and the Austrian crown controlled Charleroi fortress.

During the campaigns in the beginning of the War of the First Coalition, Charleroi changed hands several times between the Spanish, French, and Austrians crowns, variously undergoing improvements or partial demolitions. Famous French military engineer Sebastien de Vauban rebuilt the fortress in the same footprint, with several additional outlying redoubts and lunettes. The French built a bridge across the Sambre River to allow for easier shifting of reinforcements from France.

The 3,000 Austrian troops garrisoning the formidable fortress repulsed three attempts by the French to capture it. Each time, the French suffered heavy losses. In response to the failed attempts, a 52,000-strong French grand army was created to take Charleroi. The grand army comprised divisions from the Army of the North under General Jean Baptiste Kleber, the Army of the Ardennes under General François Marceau, and the Army of the Moselle under General Jean-Baptiste Jourdan. The whole of the French force was overseen by representatives Louis Saint-Just and Philippe Le Bas. None of the three commanders was willing to accept another as his superior. This compelled Saint-Just and Le Bas, on their own authority, to appoint Jourdan as overall commander. Jourdan deployed his ample forces in a ring around Charleroi in order to protect the troops besieging the fortress from attack by an Austrian relief army.

The son of a surgeon, Jourdan enlisted in the army at the age of 16 and participated in the Siege of Savannah during the American Revolutionary War. Afflicted with malaria, he was discharged several years later. The French Revolution of 1789 found him a respectable dress-shop owner in his hometown of Limoges. When the Limoges National Guard battalion was raised, Jourdan was elected as a captain of its light company. A natural leader and capable tactician, four years later Jourdan was a general of division—the equivalent of a major general.

After his victory over the British at Hondschoote on September 8, 1793, Jourdan was appointed to command the Army of the North, a posting he accepted with some reservations. The two previous commanders of the Army of the North, Adam Philippe Count de Custine and Jean Nicolas Houchard, had been arrested on trumped up charges and executed.

Well aware that Charleroi could not be reduced without a proper siege, Jourdan resolved to wait for arrival of the siege train, despite being harangued by Saint-Just and Le Bas demanding action. Upon the siege train’s arrival, Jourdan gave orders to advance on June 12. Approaching Charleroi, Jourdan tasked General Jacques Hatry’s division with conducting the siege while the rest of combined armies formed an outer ring around the fortress, busily constructing earthen fieldworks facing outward. An offer of surrender was made and rejected, and the Austrian garrison was determined to await the relief by the Allied field force led by 57 year-old Field Marshal Count Frederick Josias of Saxe-Coburg.

Saxe-Coburg was a scion of the highest nobility of the Holy Roman Empire and a future great-great-uncle of the British Queen Victoria. Entering Austrian service as a lieutenant at the age of 18, Saxe-Coburg first saw combat in the Seven Years’ War, rapidly rising through the ranks and gaining extensive experience fighting the Ottoman Turks.

Although Coburg enjoyed the unity of field command, he was severely hamstrung by diverging political agendas emanating from London, Berlin and Vienna. Relationships between Prussia and England were cool, while both Prussian and Austrian attention was distracted by a Polish uprising in March of 1794. Austrian and Prussian troops, which were vitally needed on the French front, were diverted to Poland instead to assist Russia in suppressing the uprising. Having just wrapped up another war with the Ottoman Empire, Russia was not interested in becoming embroiled in a conflict 800 miles away.

Marching to relieve Charleroi on June 16, 1794, a 41,000-strong Austro-Dutch force under Coburg emerged from the thick fog behind glinting bayonets. Caught unaware, the French had little time to form up before the Dutch troops leading the allied army quickly deployed several artillery batteries. Their rapid fire disordered the French formations, with the Austrians and the Dutch quickly following up with an infantry attack. Under strong pressure, General Marceau’s command was forced to abandon its positions at the Wanfersee hamlet and the Lambusart Woods, exposing French right flank.

A determined Austrian flank attack routed the French main body and drove it back across the Sambre River. The Austrians entered Fleurus just as the French were departing the town. The fiasco cost the French close to 3,000 killed and wounded and eight guns captured. The Allied losses amounted to 2,200 Austrian and 800 Dutch casualties. In the belief that he had chased the French away for good, Coburg withdrew his command after demolishing French fieldworks.

After restoring order, Jourdan ordered him men back across the Sambre on June 18 for the fifth time. Both Saint-Just and Le Bas pressured him to reengage the Austrians. Jourdan’s force reached Charleroi with almost no opposition from the Austrian garrison and began rebuilding seigeworks around the fortress.

Another attempt by the French to storm Charleroi was beaten back with losses. The vanguard commander, General Francois Joseph Lefebvre, reported running out of artillery ammunition. Saint-Just quickly found a scapegoat in the person of a hapless artillery captain, who was arrested and sent to the guillotine. It was later discovered that Saint-Just had prepared a proscription list of several generals. Jourdan was at the top of the list. He was targeted apparently for standing up to Saint-Just’s unwanted and uneducated advice on military matters.

Once the siegeworks were completed, a cannonade commenced and went on for five days in hopes of inducing the Austrian garrison to surrender. The Austrians stood firm; indeed, they even launched several sorties to disrupt the siege work of the French troops. Austrian positions near the hamlet of Lambusart opposite Lefebvre’s division were particularly well-entrenched. Their fieldworks were enhanced by the rough terrain in which they were located.

Representatives Saint-Just and Le Bas were not satisfied with the slow pace of the siege, visiting the seigeworks daily and harassing engineer Colonel Marescot, who was directing the siege. At one point, Saint-Just found the work on a new battery was not being conducted as quickly as he would have liked.

“When will the battery be completed?” Saint-Just inquired of a captain overseeing the work.

“It will depend on the number of workers I’m given,” the captain replied. “But I assure you they will work tirelessly.”

“If it is not ready by six o’clock tomorrow, your head will roll!” Saint-Just said.

Jourdan learned that Coburg had been reinforced by additional forces, and he believed it was no longer feasible to continue the siege while strong enemy forces could approach from the rear. It was now necessary to quickly capture Charleroi or abandon the siege. On the morning of June 25, the French stood ready to assault the fortress yet again. An officer was sent to Charleroi under a flag of truce, carrying a letter to the Austrian commander that included a message from Saint-Just. “The General-in-Chief of the Army of the Sambre is ordered to assault the town of Charleroi and put the garrison to the sword if the town does not surrender within an hour,” the message stated.

The Austrian garrison commander had no doubts about Saint-Just making good on his threat and quickly sent back his own aide with a letter containing articles of surrender. Saint-Just refused to open the letter. “You are aware of the order I gave to the general-in-chief; I have the power to give it, but I don’t have the power to retract it,” he told an Austrian officer. “I still have my and my army’s courage to carry it out. Take this answer to your general and tell him to fall upon French generosity.”

The unfortunate Austrian garrison commander promptly signed the capitulation that the French had dictated to him. The French took 2,700 enemy troops into captivity. Yet a small number of die-hards continued to hold out in outlying redoubts. No sooner was the surrender completed than the lead elements of Coburg’s vanguard arrived before Fleurus. They fired several rounds from their cannon to announce to the garrison that they had arrived. Unaware that the fortress was already in French hands, Coburg marched to Charleroi; he intended to trap Jourdan between the hammer of his field force and the anvil of the fortress.

Both sides prepared for battle that night. The French worked tirelessly to improve their outward-facing earthen fieldworks. The French built a strong outpost near Heppignies, which they aptly named the Great Redoubt.

With the reinforcements that arrived during the siege, Jourdan had on hand 75,000 infantry, 2,300 cavalry, 11 field batteries and two horse-drawn artillery batteries. The French divisions were composed of regiments, demi-brigades, and separate volunteer battalions, including infantry, cavalry, and artillery.

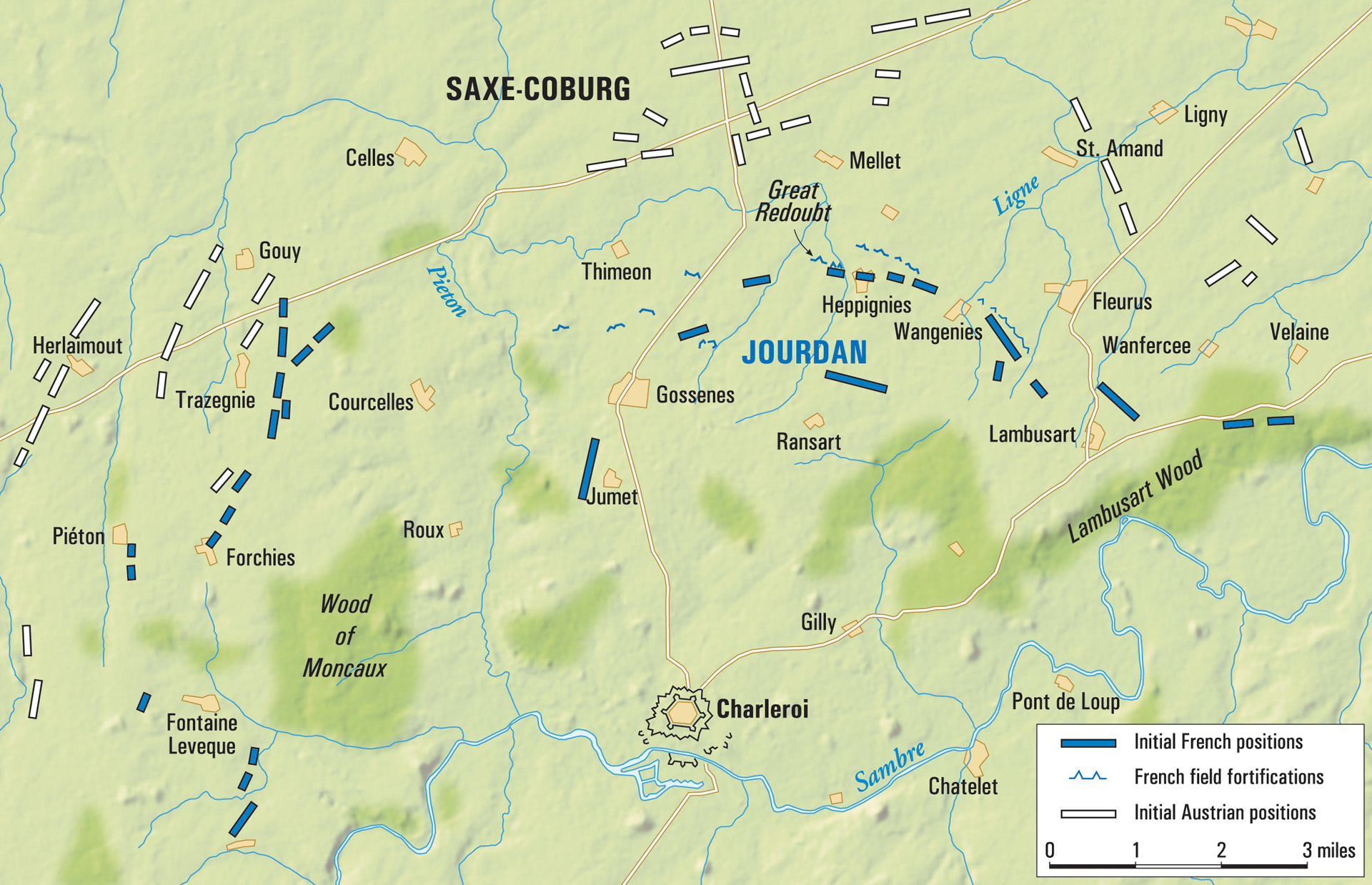

Jourdan deployed his forces in a semi-circle around Charleroi with both flanks resting on the left bank of the Sambre River. The left wing was given to Kleber’s Army of the North. Kleber placed General Charles Daurier’s brigade on the far left, with its left flank resting on the Sambre River, at the hamlet of Fontaine-l’Eveque. On Daurier’s right was the division under General Charles Montaigu at Trazegnie and Courcelles. Kleber placed his own infantry division in reserve of the left flank at Gosselies. Only a few scattered pickets occupied the right bank of the Sambre, where they kept watch for the arrival of additional Allied forces.

Jourdan’s Army of the Moselle held the center of the French line. General Antoine Morlot’s division was on its left at Mellet, in contact with Kleber. General Jean Ettiene Campionnet’s division was at Heppignies and Wangenies.

General Francois Joseph Lefebvre deployed on Championnet’s right to hold the Lambusart Woods. Lefebvre’s vanguard occupied the village of Fleurus. Two divisions of the Army of the Ardennes under General Francois Marceau took up a position on the far right of the French line, with its right flank anchored on the Sambre River. General Jacques Maurice Hatry’s infantry division, as well as a cavalry division led by General Paul-Alexis Dubois—both of which were held in reserve—assembled on the northern outskirts of Charleroi.

Saxe-Coburg’s Austrian-Dutch army was composed of 32,000 infantry, 14,000 cavalry, and 50 guns. While the French army was still homogenous at this stage, the Allied army represented a mixed bag of soldiers from a half-dozen European countries. The Dutch Army had not gone to war for more than a half century. Because of this, its army had severely declined in effectiveness. Its soldiers were inexperienced, and its older generals very old. Saxe-Coburg also had two Swiss battalions and several French émigré units, which were spread among his Dutch troops. The Royal-Allemand Cavalry Regiment was composed of French-born German speakers.

The backbone of the Allied army was the white-coated Austro-Hungarian regiments. The men were steady and brave, despite being poorly led. The officers lacked experience, and they tended to be extremely conservative in their thinking. It is worth noting that no other nation fought as often, or put more troops in the field, than Austria did during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars.

Saxe-Coburg’s three corps went into battle arrayed in five columns. The first column, which was commanded by Prince William V of Orange, the Stadtholder of the Dutch Republic, consisted primarily of Dutch and French émigré troops. They deployed on the Allied right flank opposite Kleber’s command. The other four columns were composed of Austrian troops with a few émigré units integrated with them. Facing Jourdan’s Army of the Moselle in the center, Saxe-Coburg personally commanded three columns under Field Marshal Peter Quasdanovich, Field Marshal Count von Kaunitz-Rietberg, and Field Marshal Archduke Charles. Field Marshal Johann Peter Beaulieu’s fifth column, on the Allied left, deployed facing Marceau’s troops in the section of the line of battle that stretched from Fleurus to the Sambre River.

The Allies made the first move on June 26. The battle began before sunrise with the Dutch cavalry conducting a wide sweep through Anderlues on the French left. Their objective was the hamlet of Landmeier on the left bank of the Sambre.

Daurier’s brigade staunchly held its position, preventing the Dutch from reaching the bridge over the river. The Prince of Orange’s infantry lunged at the divisions of Montaigu and Moller. The Dutch foot succeeded in capturing the hamlets of Forchies and Trazegnies. In so doing, they drove the French east toward Charleroi.

The French found themselves in a dire predicament three hours later. Beulieu’s column on the right flank followed the same route it had 10 days previously, and it once again overran Marceau’s position. The Austrian attack unfolded so rapidly and furiously against the French at the hamlets of Wanfersee and Velaine that a portion of Marceau’s command fled in disorder to the right bank of the Sambre. In so doing, they left Marceau alone with his staff officers and some artillery to face the enemy.

The Austrian column continued along the left bank of the Sambre toward Charleroi. Seeing the disaster unfolding to his right, Lefebvre sent his chief of staff Colonel Nicolas Soult to ascertain the situation. He entrusted Soult to act on his authority as the situation required.

When Soult found Marceau, the “boy general” was distraught from the shameful flight of his troops. In anguish, 22-year-old Marceau pulled out his pistol and pointed it at his head to wash away the shame of his troops.

“You want to die, and your soldiers dishonor themselves,” Soult, stopping Marceau from taking such a drastic act. “Go look for them and come back to win with them.” Marceau followed Soult’s sage advice. Acknowledging it was a “path to honor,” Marceau galloped off to find his troops, while Soult rode to Hatry’s division and brought up an infantry brigade to plug the gap left by Marceau’s fleeing troops. Two hours later, having chased down and rallied his errant divisions, Marceau brought his troops back in the battle line.

By late morning the Austrians had driven back the French on both flanks. On the right, even though the situation had somewhat stabilized, the French were pushed back to the outskirts of Charleroi. On the left, Montaigu’s divisions were driven beyond the Pieton River, a small tributary of the Sambre. At the same time, Dutch cavalry probed towards Marchienne, where the French siege artillery was assembled.

A Dutch cavalry patrol penetrated to the outskirts of Charleroi, where a small Austrian unit from Cahrleroi’s garrison was holding out in an outlying redoubt. In order to prevent the Dutch from crossing the river in force, Kleber reinforced the troops at Marchienne and destroyed the bridge there.

In the center, where main bodies of both armies clashed near Fleurus, the situation settled into a bloody stalemate. Lefebvre’s vanguard was ejected from Fleurus by Archduke Charles’ column and withdrew to join the rest of the division at Lambusart. Charles then continued his advance to Gosselies, which was situated on the northern outskirts of Charleroi. But the main battle line of Lefebvre’s and Championnet’s divisions held fast. Units advanced within musket range and traded volleys until one side broke. Disordered units would fall back to rally, fresh units would take their place in the line of battle, and the process would repeat itself.

With the French right flank compromised, Beaulieu led his Austrian column to attack Lambusart. The light troops of Lefebvre’s vanguard, which had withdrawn to Fleurus, defended the gardens and the entrance to the village as a gap in the French line developed from the Lambusart Woods to the Sambre. Under orders from General Lefebvre, Soult led three infantry battalions and a dragoon regiment to fill the gap. An artillery battery from Marceau’s command, left behind in the general rout, took up a position in Lefebvre’s battle line.

The Austrian column under Quasdanovich pushed Morlot’s division from the hamlet of Mellet. Another column under Kaunitz captured the Great Redoubt. All French attempts to recapture it were beaten back with losses, while artillery and musket fire from both sides set afire fields of ripe wheat surrounding the Great Redoubt.

When a strong Austrian column advanced on Lefebvre’s position at Campinaire, he ordered his troops to hold fire until the Austrians were within a stone’s throw. A devastating musket volley opened huge gaps in the Austrians’ ordered lines. The volley was immediately followed by a charge of General d’Hautpoul’s light cavalry, routing the Austrian column.

The dogged Austrians kept coming back. Archduke Charles’ column attacked three times without success. Beaulieu’s column also had little success at Lambusart and against the French line placed at right angles between the village and the woods. Charleroi stood like an island surrounded by a sea of fire and smoke; Jourdan looked to the northwest, where he expected to see a relief column of 1,500 men arrive at any time.

Saxe-Coburg not only found his troops fought to a standstill in the center, but also learned of the fall of Charleroi to the enemy. At that point, he began to consider retreat rather than continuing the battle. Casualties were mounting in the Allied ranks, and the French appeared to be fighting with renewed vigor.

The Austrian commander exhibited great determination. He launched another assault against the long-suffering French right flank. The column under Beaulieu attacked against Lambusart and cleared the hamlet of the French, who managed to hang on to a small number of houses on its edge. Further Austrian progress in Lambusart was halted by the French setting fire to buildings, thus creating a flaming barrier between combatants.

Ten Austrian cavalry squadrons attacked hedgerows that were staunchly defended by the French. Well-directed musket volleys and grapeshot shattered the Austrians’ mounted attack. Countercharged by a French battalion and a dragoon regiment, the Austrian cavalrymen fell back. The fighting was so intense that one French colonel had five horses shot from under him.

At this critical juncture, Kleber sent his Army of the North in a general advance against the Allied right flank across the Pieton River. Meanwhile, Colonel Jean Bernadotte’s demi-brigade and a cavalry regiment attacked toward Forchies, while Colonel Duhesme advanced with three regiments against Courcelles. On the far left, steadfast Daurier’s brigade attacked the Dutch right flank.

With both of his wings secure by late afternoon, Jourdan led his troops forward. He attacked with Championnet and Morlot’s infantry divisions, which were supported by Dubois’ cavalry division. Lefebvre advanced his reserves against Lambusart, and even Marceau’s rallied battalions participated in the general advance, supported by a brigade from Hatry’s divisions. Although Kaunitz was still in firm control of Heppignies with Quasdanovich supporting him astride the road to Brussels, Saxe-Coburg lost heart and gave orders for his troops to withdraw.

The first Austrian line became so disordered that several of its artillery batteries fell into French hands, but the second line held fast. Austrian cuirassiers covering the withdrawal countercharged and were able to retake their lost artillery. Until then, Beaulieu had continued attacking French entrenchments, but now—charged on the flank—he was forced to withdraw. The whole of the Allied line began falling back. However, they withdrew in relative order, with Quasdanovich and Kaunitz giving them time to disengage.

Nightfall brought an end to the fighting except for some desultory skirmishing, and the Allies were withdrawing without interference from the French. Even though some French commanders were calling for pursuit, the French, engaged for almost fifteen hours, were exhausted and almost out of ammunition. Jourdan finally ordered his command to stand down.

An invention previously unseen on a battlefield made its debut at the battle of Fleurus: the world’s first military reconnaissance balloon. The hydrogen-filled balloon l’Entrepremant was constructed in 1793 by French scientists Charles Coutelle and Nicolas-Jacques Conte.

When Coutelle demonstrated the balloon to members of the Committee for Public Safety, they were so impressed with it that they authorized the creation of the first air force, called Compagnie d’Aeronautiers. Established on March 29, 1794, the company numbered just 30 men, all of whom were tradesmen with skills applicable to carpentry and balloon-making. Coutelle was commissioned a captain and given command of the newly created company.

Deployed for the siege, l’Entrepremant was inflated at Maubege on the French side of the border and towed by ropes to Charleroi. When the battle at Fleurus began, the balloon was raised behind the French lines, with Coutelle and an observer officer riding up in its gondola. Coutelle operated the balloon in conjunction with the ground crew; the observer communicated by use of signal flags and by sending down messages in a weighted bag fitted with rings to slide down a rope. The Austrian troops took pot shots at the balloon, and Coutelle was forced to raise it higher.

Even though much credit has been given to the balloon’s contribution to the battle, Jourdan was skeptical regarding its effectiveness. Soult was not so charitable. “I will say nothing about the balloon that was hovering over the heads of the combatants during the battle, and this ridiculous innovation would not even have deserved to be cited if it had not been given an important role,” he said, giving a detailed account of the tedious steps involved in such a reconnaissance. “At the height to which they were allowed to climb, the details escaped their sight and everything was confused. We were not better informed about it and no one paid attention to it, neither the enemy nor ourselves.”

The French remained on the field the next day, recovering and counting their losses. Both sides suffered approximately 5,000 casualties. Among the prisoners taken by the French were some of their émigré former countrymen. Although a law was in effect sentencing to death those émigrés taking up arms against the Republic, no executions were carried out. Both sides were tired of the bloodletting, which Soult later described as “15 hours of the most desperate fighting I ever saw in my life.”

Saxe-Coburg initially withdrew his forces a short distance and reformed his columns for renewed combat in the morning; however, he changed his mind during the night, considering himself beaten. The Allied forces withdrew to Waterloo, 25 miles way, which in 1815 would become one of the most pivotal battles in world history.

The day after the battle, Saint-Just and Le Bas rushed to Paris with the good news, arriving there just in time for Saint-Just to be arrested along with Robespierre when the Jacobin regime was overthrown. Revolutions tend to turn on their makers, and it was now the Jacobins’ turn to face the terror they had unleashed. Robespierre and Saint-Just were sent to the guillotine on July 28. When Saint-Just’s turn came to die, he begged for his life in vain. Le Bas, who successfully evaded arrest, committed suicide the same day.

Shortly after the victory, the Committee of Public Safety confirmed Jourdan’s appointment in command of newly renamed Army of Sambre-and-Meuse. Four of Napoleon’s future marshals—Jourdan, Lefebvre, Soult, and Bernadotte—fought at Fleurus, gaining valuable leadership experience.

Even though the Battle of Fleurus was a draw, its far-reaching political consequences outweighed the military significance of the victory. Allied objectives were dictated from each capitol, and political goals far outweighed military necessity. Rather than withdrawing north to link up with the British and Hanoverians, Saxe-Coburg began moving east across the Rhine River. Austrian withdrawal robbed the Allies of much-needed manpower.

When French General Jean-Charles Pichegru renewed his offensive in the winter of 1794-1795, the Dutch army disintegrated, and the British evacuated across the English Channel to their home islands. Prince William of Orange, the Dutch Stadtholder, fled to England. The French government reconstituted the Dutch Republic as a French client state known as the Batavian Republic.

As for Prussia, which was forced to divert significant forces to assist Russia in putting down the Polish uprising in March 1794, Prussian King Frederick William II no longer had interest to fight in the west, having made significant territorial gains in the east in the eventual Second Partition of Poland.

Frederick William concluded a separate agreement known as the Peace of Basel with France in 1795 that recognized French territorial gains. The Austrians did not accept the loss of the Austrian Netherlands until 1797, when they signed the Treaty of Leoben. Even though the First Coalition collapsed after the Battle of Fleurus, successive coalitions rose up like heads of a hydra to battle France.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments