By Mason B. Webb

Lately, many of the scores of books published on the topic of World War II purport to be the “untold story” of such-and-such battle, campaign, or event; very few of them are actually untold stories, and most are merely the rehashing of the familiar. However, Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway (Potomac Books, Washington, D.C., 2005, 613 pp., photographs, maps, schematics, charts, index, bibliography, $35.00, hardcover) by Jonathan Parshall and Anthony Tulley truly lives up to its subtitle.

Basing their weighty volume on a considerable trove of heretofore untranslated primary-source Japanese documents, Parshall and Tully, two well-known authors and scholars of the Pacific War, have done a remarkable job in correcting many of the myths and half-truths that have attached themselves over the decades to the 1942 Battle of Midway.

Basing their weighty volume on a considerable trove of heretofore untranslated primary-source Japanese documents, Parshall and Tully, two well-known authors and scholars of the Pacific War, have done a remarkable job in correcting many of the myths and half-truths that have attached themselves over the decades to the 1942 Battle of Midway.

Seeing the battle primarily through Japanese eyes, Parshall and Tully have crafted a truly original and exhaustively-researched work that provides a full dimension to the pivotal battle. Numerous maps show how the various phases of the battle developed, and many photos from Japanese sources paint a more complete picture than ever before.

As noted naval expert John B. Lundstrom says in the foreword, “I was truly shocked to learn from Jon and Tony that much of what [Commander Mitsuo] Fuchida wrote about the Battle of Midway (and some on Pearl Harbor for that matter) has been debunked in Japan, where a whole corpus of historical thought on Midway remained untapped in the West…. Shattered Sword is without doubt the most significant and balanced treatment of the Japanese side of the Battle of Midway, and is likely to remain so for the foreseeable future.”

This is not “revisionist” history in the sense that it is iconoclastic. But Shattered Sword does an important job of revising what we in the West for too long thought we knew about the Battle of Midway.

Much of what the West knows about Japanese carrier operations at Midway was based on Fuchida’s 1953 book which, Parshall and Tully point out, was seriously flawed by his desire to color the facts for domestic consumption and put the best face possible on disaster. As the authors say, “After all, Japan had just suffered an enormous national humiliation, one particularly devastating to a society that viewed itself as uniquely superior…. Some sense of national pride might be regained by revealing some moments of nobility within that defeat.”

One can only hope that Parshall and Tully are working on future volumes that will bring a similarly new and fresh perspective to the rest of the Pacific campaign.

Louis Johnson and the Arming of America, by Keith D. McFarland and David L. Roll, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2005, 452 pp., photographs, index, bibliography, $23.00, hardcover.

Louis Johnson and the Arming of America, by Keith D. McFarland and David L. Roll, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2005, 452 pp., photographs, index, bibliography, $23.00, hardcover.

It is probably safe to say that few post-war Americans are familiar with the name Louis Arthur Johnson. All but unknown today, he was, during the Roosevelt and Truman administrations, one of the most powerful figures in America.

Described variously as arrogant, rude, abrasive, insensitive, intelligent, gregarious, articulate, and eternally optimistic, Louis Johnson antagonized those both above and below him, thereby sowing the seeds of his own downfall.

Big and beefy (240 pounds), Johnson, a college boxing champion and World War I veteran, came to Roosevelt’s attention in the mid-1930s after serving as head of the American Legion. The first third of the book deals with Johnson’s relationship with Roosevelt and his efforts to alert the isolationist nation to the growing threat he saw building in Japan, Germany, and Italy. From the time he started his job as FDR’s Assistant Secretary of War in the summer of 1937, he did all he could to mobilize America for the coming war. But in June 1940, Johnson was released from his duties as FDR’s chief war planner and appointed the president’s special envoy to India—a task that turned out to be frustrating and thankless.

After the war, Johnson returned to his life as a lawyer, but his political career was soon resurrected. In 1948, when no one stepped forward to take charge of fundraising for Harry Truman’s faltering presidential campaign, Johnson volunteered; his efforts rescued the campaign from certain defeat. As a reward, Truman made Johnson Secretary of Defense (replacing the mentally ill James Forrestal, who committed suicide) from 1949-1950.

A fanatical budget slasher under Truman, Johnson had the heads of the armed services howling in protest. Only the start of the Korean War in June 1950 brought a halt to his fiscal austerity crusade; Johnson was suddenly faced with having to hurriedly rebuild the military in order to throw back the Reds.

While his tenure as Secretary of Defense was brief, his accomplishments were many. He was deeply involved in the establishing of NATO, as well boosting America’s atomic arsenal and championing the development of the hydrogen bomb.

But ambition got the better of him (he wanted to be president). His bitter feud with Secretary of State Dean Acheson was legendary, and Truman suspected Johnson was disloyal, firing him just two days before Douglas MacArthur’s bold invasion of Inchon, Korea, that turned defeat into, if not victory, at least a stalemate that prevented defeat.

Delving into the dusty archives at Steptoe and Johnson (Johnson’s Washington D.C. law firm where co-author Roll works as a lawyer), the authors have crafted a very readable biography of the only civilian who shaped the national security and military preparedness of both the Roosevelt and Truman presidencies to meet the exigencies of both World War II and the Korean conflict. The book sheds considerable light on the behind-the-scenes machinations within the corridors of power.

Pacific Warriors: The U.S. Marines in World War II—A Pictorial Tribute, by Eric Hammel, Zenith Press, St. Paul, MN, 2005, 256 pp., photographs, maps, index, bibliography, $40.00, hardcover.

Pacific Warriors: The U.S. Marines in World War II—A Pictorial Tribute, by Eric Hammel, Zenith Press, St. Paul, MN, 2005, 256 pp., photographs, maps, index, bibliography, $40.00, hardcover.

The acclaimed author of 28 books of military history has brought his expertise to bear on the U.S. Marine Corps’ entire combat history in the Pacific.

Opening with two chapters on the early days of the Corps and its battle experiences in the Spanish-American War and subsequent engagements in Mexico, Nicaragua, and the Caribbean until the last days of peace in December 1941, Hammel lays the groundwork of the horrendous Pacific island battles to follow in this handsome, oversized (11 x 12.5) volume. From the invasion of Guadalcanal in August 1942, to the blood-letting on the threshold of Japan—Okinawa—in April 1945, Pacific Warriors chronologically follows each grim Marine campaign on America’s road to Tokyo.

Hundreds of superb quality photographs, an astonishingly high number of them reproduced here for the first time—and more than a few not for the squeamish—provide the reader with a Marine’s eye view of combat. Hammel’s prose also details the enormous obstacles the Marines had to overcome on each of their amphibious assaults.

In the chapter on Peleliu, he writes, “Most, perhaps all, of the battalion’s medium tanks were knocked out at one time or another during the campaign, but most were speedily returned to duty by expert, dedicated repair crews. The tanks made all the difference on Peleliu. The infantry was no less magnificent. It took utmost teamwork and bravery to advance on hidden, mutually supported bunkers and caves, and these were traits the Marine infantry possessed in abundance. With or without the support of the tanks, the infantry steadily reduced bunker after bunker, cave after cave, and defensive locale after defensive locale. The price was exorbitant, but the gains from D+1 onward were considerable.”

The legend of the Marine Corps was written in blood and fire across the islands of the Pacific, and Hammel’s pictorial tribute is indeed a loving tribute.

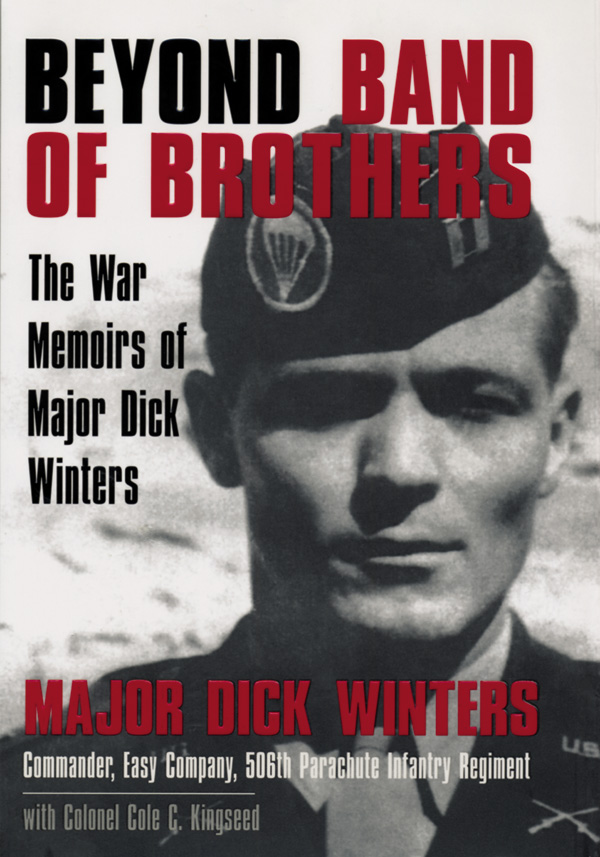

Beyond Band of Brothers, by Major Dick Winters (with Colonel Cole C. Kingseed), Berkeley Caliber, New York, 2006, 320 pp., photographs, maps, index, $24.95, softcover.

Beyond Band of Brothers, by Major Dick Winters (with Colonel Cole C. Kingseed), Berkeley Caliber, New York, 2006, 320 pp., photographs, maps, index, $24.95, softcover.

Dick Winters is a name that anyone familiar with Stephen Ambrose’s Band of Brothers and the HBO television series of the same name will instantly recognize. He was the commander of Easy Company, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division. At long last, he has published his memoirs—and the wait has been worth it.

Here are the eyewitness accounts of some of the toughest, most storied battles of the European phase of World War II written by the officer who led the way. Unsparing in his view of combat, courage, and cowardice, Winters tells it like it was.

His descriptions of being under fire are riveting. Describing the flight across the English Channel and the jump into Normandy, Winters writes, “As the Germans illuminated the night with searchlights and antiaircraft fire, the pilots naturally began taking evasive action. We came in too fast and too low. I did not realize it at the time, but the plane carrying Lieutenant Meehan was hit and plunged toward the earth, killing Easy Company’s entire headquarters section save myself… On the outskirts of Ste. Mere-Eglise, I saw a large fire, which turned out to be a downed plane… I had lost my weapon. When I landed, the only weapon I had was a trench knife that I had placed in my boot. I stuck the knife in the ground before I went to work on my chute. This was a hell of a way to begin a war.”

Also riveting is his disdain for those rear echelon types who kept out of harm’s way but puffed up their own resumes to make themselves seem like heroes.

He recalls the day he met SHAEF’s combat historian S.L.A. Marshall gathering airborne war stories that subsequently would be published in his book, Night Drop. “[Marshall] alleged that less than 20 percent of the [airborne] soldiers actually fired their weapons in combat [on D-day in Normandy]. Marshall obviously had not visited Easy Company, because all its troopers had been decisively engaged. Moreover, Marshall concentrated on the experiences of West Point officers and paid scant attention to those front-line officers who had not graduated from the U.S. Military Academy…. My personal encounter with Marshall was relatively brief. He pulled me into a tent with all the senior officers to discuss Easy Company’s role on D-Day. There was a hell of a lot of brass in that tent, all anxious for Marshall to make them famous. I couldn’t have cared less…. As a result, Marshall didn’t say anything special about Easy Company––and what he did say was totally fabricated.”

What Winters has written is not fabricated. Beyond Band of Brothers is destined to become an instant classic of men at war, ranking with Charles MacDonald’s Company Commander. Run, don’t walk, to get this one.

The Final Hours: The Luftwaffe Plot Against Göring, by Johannes Steinhoff, Potomac Books, Washington, D.C., 2005, 220 pp., photographs, map, index, $19.95, softcover.

It is easy, given the timespan of history, to regard the Nazi regime as all marching in lockstep, following their beloved Führer without question. Of course, such a picture would be false and few books illustrate that fact better than Steinhoff’s. The Luftwaffe colonel’s searing memoir paints a behind-the-scenes portrait of the German Air Force, at least in the dying months of the war, as being disillusioned, doubtful of victory, and determined to rid themselves of their leader, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, whom they were convinced was leading Germany and the Luftwaffe to disaster.

Steinhoff, a heavily decorated, high-scoring ace, commanded an elite group of pilots trained to fly the world’s first combat jet fighter, the Me-262. In the futile hope of forestalling final defeat in the air in the autumn of 1944, Göring had sent the small fleet of jet fighters on hopeless missions to shoot down the daily waves of B-17 bombers that were turning Germany into a charnel house. Steinhoff and other senior air leaders became determined to depose their commander for, among other things, his failure to properly employ the Me-262s for which the Allies had no defense.

Steinhoff recounts the pressure of fighting for an evil regime and how an unstable command fostered disloyalty and conspiracy. His book reveals the inner turmoil of his struggle to survive and the temerity of his fellow pilots to risk punishment for speaking out about a cause that they considered hopeless and a commander they considered incompetent—a commander who branded his best pilots “cowards.”

At last the pilots rebelled. After reciting a long list of grievances, Steinhoff confronted his immediate superior and demanded in no uncertain terms that Göring be dismissed and replaced. “I’d said it,” notes Steinhoff. “The last sentence rang in my ears as if I had shouted it at the top of my voice. Something had just occurred that Wehrmacht regulations made no provisions for: a colonel had demanded that his ultimate military superior be removed from his post! Von Greim could have had us arrested and court-martialed for mutiny. To my surprise, though, his face betrayed something more like amazement, possibly even a trace of amusement.”

But it was too late in the war; Göring was not dismissed and Steinhoff was not disciplined. After crashing his Me-262 during takeoff in April 1945, the badly burned and horribly disfigured Steinhoff had time to ruminate about Germany’s future while lying in the hospital (which was under the control of the Americans). He dictated to another wounded soldier what would eventually become The Final Hours.

This is a superbly written account by a leading member of a very small band of elite warriors. Besides recounting several instances of exciting aerial combat in the jet-powered planes, Steinhoff provides a rarely glimpsed look at the inner workings of a legendary, if dysfunctional, military force. His account is illuminating, and the picture he draws of courage and devotion to duty in the face of certain defeat is both heartening and heartbreaking.

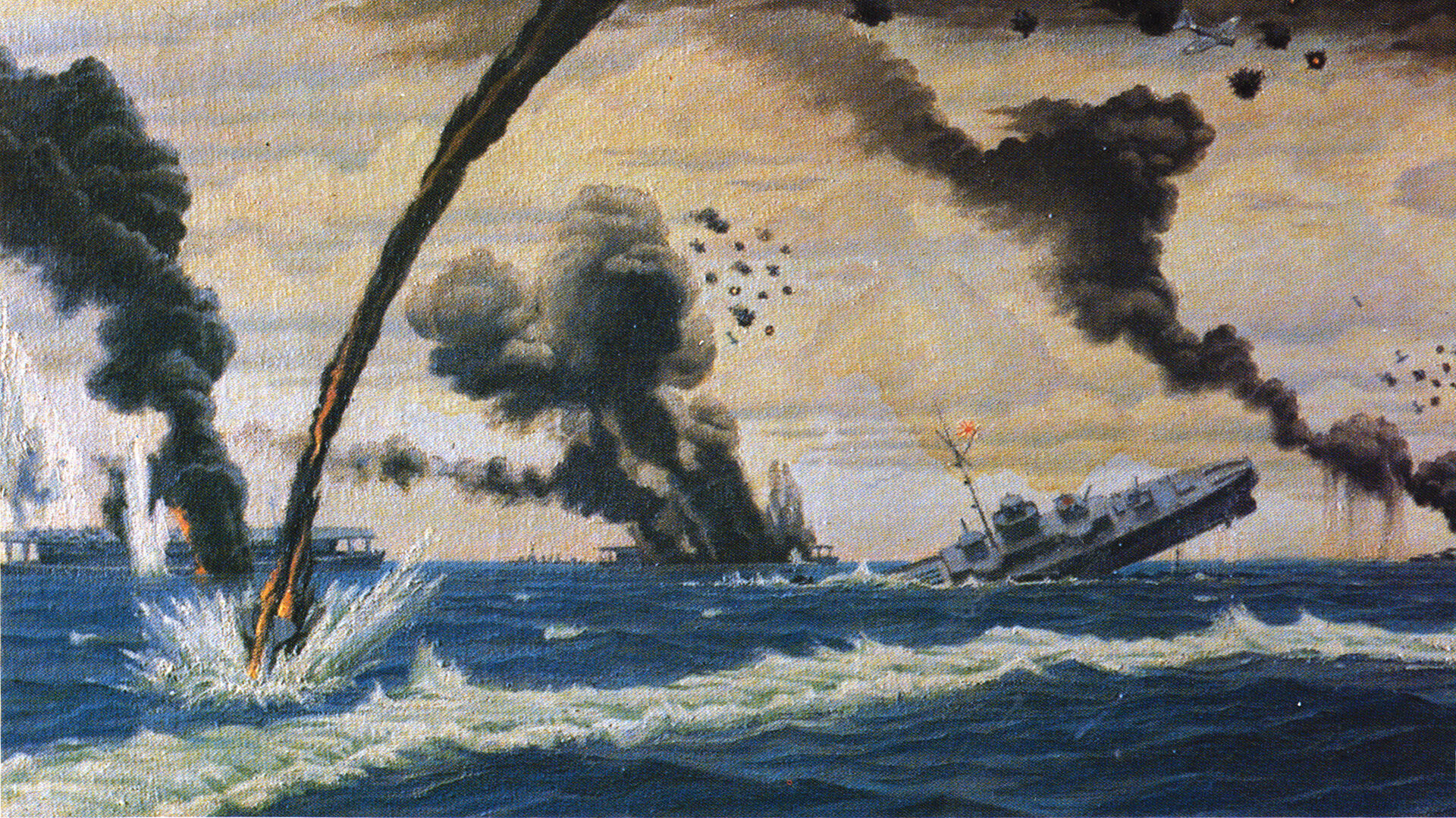

Clash of the Carriers: The True Story of the Marianas Turkey Shoot, by Barrett Tillman, NAL Caliber, New York, 2005, 348 pp., photographs, maps, index, bibliography, $24.95, hardcover.

Clash of the Carriers: The True Story of the Marianas Turkey Shoot, by Barrett Tillman, NAL Caliber, New York, 2005, 348 pp., photographs, maps, index, bibliography, $24.95, hardcover.

The Battle of the Philippine Sea, in June 1944, quickly became known as the “Great Marianas Turkey Shoot” because the now-obsolescent Zero aircraft and the inexperienced Japanese carrier pilots—who had been rushed through training following the twin debacles of Coral Sea and Midway—were no match for the well-trained, combat savvy Americans and their Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters.

Barrett Tillman, naval aviation’s most prolific chronicler, brings the greatest air battle of all time alive with a superb new history of the Battle of the Philippine Sea.

On June 13, Operation Forager, the American invasion of Saipan—supported by Admiral Raymond Spruance’s Fifth Fleet and its striking arm, Marc Mitscher’s Fast Carrier Task Force 58, with 535 ships of all descriptions and 905 aircraft distributed across 15 carriers—began. A total of 71,000 Americans came ashore at Saipan, 1,200 nautical miles south of Tokyo.

In an attempt to sweep them off the small island and cripple Mitscher’s fleet, Japan sent a large armada, including eight carriers, 440 aircraft, and the two biggest battleships in the world, the Yamato and Musashi, steaming toward Saipan. To Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa’s assembled fleet the Japanese warlords radioed the following message: “The fate of the Empire rests on this one battle. Every man is expected to do his utmost.”

During two days of aerial combat, the planes of the American and Japanese carriers dueled without pause, launching wave after wave of aircraft at each other in hopes of crippling the other’s flattops.

When the sky battle finally ended, more than 400 Japanese aircraft and 3 Japanese carriers lay at the bottom of the ocean. The “fate of the Empire” had been decided. Saipan and Tinian were in American hands, and the huge aerial armadas of B-29 Superfortress bombers would soon use the islands as springboards for the devastating bombing raids—including the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki—over Japan.

Tillman’s tense account of the battle’s strategy and tactics, drawn from official records and memoirs and interviews with men from both sides, moves along at a fever pitch. Clash of the Carriers is an important testimonial to the bravery of those who fought and died in one of the most monumental battles of the Second World War.

A Stranger to Myself: The Inhumanity of War—Russia, 1941-1944, by Willy Peter Reese, translated by Michael Hofmann, Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, New York, 2005, 176 pp., photographs, map, $35.00, hardcover.

A Stranger to Myself: The Inhumanity of War—Russia, 1941-1944, by Willy Peter Reese, translated by Michael Hofmann, Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, New York, 2005, 176 pp., photographs, map, $35.00, hardcover.

“The war began, and we saw God and his stars perish in the West. Death rampaged over the earth—he took off his mask, and his skull face grinned, chiseled with dementia and pain. We set out into no-man’s-land, saw him dance in the distance, and heard the throb of drums at night.”

So begins an amazing book that many are calling the All Quiet on the Western Front of the Second World War. This slim volume recounts with painful insight how a sensitive, war-hating German lad was converted into a decorated, battle-hardened veteran.

A 20-year-old bank clerk trainee when he was drafted into the Wehrmacht in 1939, Reese spent four tours of duty during the war of devastation and annihilation on the vast, frozen front lines of Hitler’s unwinnable war against the Soviet Union.

Bearing witness to and participating in some of the worst atrocities of war, the youthful Reese had dreams of someday becoming a writer. He loved books, poetry, nature, philosophy, Bach, Beethoven, the simple pleasures of the flesh. He hated the military, stupidity, cruelty, ugliness, and the war that had been foisted upon him and members of his generation.

Yet, he was assigned to an infantry unit and soon caught up in war’s strange, terrible beauty, epic sweep, and its demands to keep marching on the treadmill toward extinction while recording everything, and forgetting nothing.

He kept notes of his battlefield experiences in a journal and on various scraps of paper. During his last furlough home he typed up his notes in manuscript form, then gave them to his mother for safekeeping. There they sat, undiscovered, unpublished. The book’s editor says, “For decades, no one was interested in Reese’s manuscript. But his memoirs might have helped make the day-to-day reality of the common soldier during the war a part of the general consciousness in Germany.”

In 2002, a cousin inherited the manuscript and, recognizing its remarkable prose, turned it over to the German popular magazine Stern, which published it in 2003 to great acclaim. An excellent translation has now brought Willy Peter Reese to the attention of the English-speaking world.

Hailed in Germany as one of the Second World War’s most important memoirs to date, Reese’s poignant accounts of life on the battlefield resonate with ambiguity and internal conflicts. At times horrified by battle, at other times exultantly taking part in its most debasing aspects, Reese gradually descends into the life of an automaton, performing his military duties without thinking, without questioning, yet never quite losing the last shreds of humanity or his ability to record the world around him and his relationship to it.

Reese’s death on the Russian Front, at age 23 and in June 1944, represented more than the loss of just another German soldier; it was also the world’s loss of a brilliant writer of great promise, whose contributions to the world of literature were unfulfilled. Who knows to what literary heights he might have climbed had his life not been snuffed out at such an early age in such a senseless conflict?

Navy Wings of Gold, by F. Willard Robinson, River Park Press, Boise, ID, 2005, 342 pp., photographs, maps, 342 pp., $19.95, softcover.

Navy Wings of Gold, by F. Willard Robinson, River Park Press, Boise, ID, 2005, 342 pp., photographs, maps, 342 pp., $19.95, softcover.

Precious little has been written by and about carrier pilots, but F. Willard “Robbie” Robinson’s memoirs do much to fill the gap.

A Navy TBM-3E Avenger torpedo plane pilot assigned to Squadron VC-7 aboard the escort carrier USS Manila Bay, Robinson describes his training and deployment to the Pacific in detail. He also recounts the harrowing crash landing in February 1944 that left him badly injured and nearly cost him his life. While coming in at dusk for a landing on the carrier with a full load of four 500-pound depth charges (the mission had failed to locate targets), Robinson’s heavy plane lost altitude too quickly and plunged into the water.

He writes, “It was too late to jettison the explosives! Without warning the plane lurched and trembled. Like a goose hit in the wing by a volley of shot, we plummeted into the Pacific with terrifying finality. The plane smashed into the water in a death dive, hitting the sea and instantly exploding in a shattering burst of water and debris…. With one last tremendous effort I tripped the release on one side of my Mae West life jacket. Then the storm passed and I was left bobbing in a sea of unreal quietness. I looked around. All was gone, the flight crew, the plane, and even the debris that usually floats from a crash.” His two fellow crewmen were both lost and Robinson was badly burned, torn apart by shrapnel, and had his legs crushed. Three subsequent chapters deal with his efforts to recover from his terrible wounds.

Robinson also includes, as an extra bonus, memoirs and interviews he made with eight other carrier pilots, including Grumman Hellcat flyer Nat Adams, who has written the only known eyewitness account of the shooting down of future president Lt. (j.g.) George H. W. Bush’s Avenger off the coast of Chichi Jima.

This is an essential book for anyone wanting a glimpse into the lives of the Navy’s valiant aerial knights.

SHORT BURSTS

American Deserter: General Eisenhower and the Execution of Eddie Slovik, by Charles Whiting, Eskdale Publishing, York, England, 2005, 234 pp., photographs, maps, index, bibliography, $24.95, hardcover.

American Deserter: General Eisenhower and the Execution of Eddie Slovik, by Charles Whiting, Eskdale Publishing, York, England, 2005, 234 pp., photographs, maps, index, bibliography, $24.95, hardcover.

“He was a Polish-American kid from the wrong side of the tracks.” So notes the prolific British military historian Charles Whiting in his detailed look into the life and death of Private Eddie Slovik, a reluctant replacement in the 28th Infantry Division and the only American soldier executed for desertion in World War II. Even today, debate rages between those who thought a grave injustice had been done to Slovik, and those who believe he got what he deserved. Troubling and thought-provoking.

Worlds Away: Following My Father’s World War II Footsteps, by Patrick M. Finelli, Paradise Press, 2005, $19.95, softcover.

A scuba diving son retraces his Marine Corps father’s exploits as a frogman by visiting the underwater graveyards of famous naval clashes. Finelli discovers an incredible amount of war debris under the sea at Truk Lagoon and on the infamous bleeding ground of Peleliu, and juxtaposes his own photos with those taken during the war. Compelling and fascinating.

War Stories III: The Heroes Who Defeated Hitler, by Oliver North (with Joe Musser), Regnery, 2005, 342 pp., $29.95, hardcover.

Fox News military analyst and retired Marine Corps Colonel Ollie North has produced the third volume in his best-selling War Stories series, this one covering the entire panoply of the European theater. Within its 342 pages, scores of veterans share their personal tales of combat in the air, on land, and on the sea with the reader. Included are spellbinding accounts by Lieutenant Bob Dole of the 10th Mountain Division, renowned fighter ace Chuck Yeager, B-24 pilot George McGovern, 1st Infantry Division Medal of Honor recipient Walt Ehlers, Lieutenant Charles Calhoun who served aboard the destroyer USS Sterrett in its deadly battles with German U-boats, Choctaw Indian and Medal of Honor recipient Van Barfoot of the 45th Division, and many others. A great read.

The Button Box: A Daughter’s Loving Memory of Mrs. George S. Patton, by Ruth Ellen Patton Totten, University of Missouri Press, 2005, $34.95, hardcover.

If the old adage, “Behind every great man is a great woman” is true, then the wife of Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr., is as deserving of as many accolades as her husband. This highly absorbing book, written by the Pattons’ daughter, is an engaging, never-before-told account of her parents’ lives—especially her extraordinary mother, Beatice Banning Ayer. As Ruth Ellen points out, her mother, a woman from a wealthy Boston family and an accomplished equestrian, sailboat racer, musician, and author, had a profound impact on the general, and doubtless helped make him the man he was. This is an indispensible book for anyone who wants to know more about the hidden side of one of America’s greatest warriors.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments