By Mason B. Webb

One of the most common beliefs that has arisen since the end of World War II is that America and her allies had as one of their primary goals for fighting the war ending the systematic slaughter of Europe’s Jews. Such a belief, undoubtedly, has stemmed from all of the books, articles, documentaries, and Hollywood films that have been produced about the Holocaust over the past six decades.

Yet, the common belief is wrong. As Theodore S. Hamerow, the author of Why We Watched: Europe, America, and the Holocaust (W.W. Norton, New York, 2008, 520 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $35.00) and a professor emeritus of history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison points out, the U.S., Britain, and other allies did very little to stop the genocide as it was being perpetrated. Anti-Semitism in America and elsewhere, while not as horrendous as that which was taking place in Germany, was alive and well on American and British shores.

Yet, the common belief is wrong. As Theodore S. Hamerow, the author of Why We Watched: Europe, America, and the Holocaust (W.W. Norton, New York, 2008, 520 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $35.00) and a professor emeritus of history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison points out, the U.S., Britain, and other allies did very little to stop the genocide as it was being perpetrated. Anti-Semitism in America and elsewhere, while not as horrendous as that which was taking place in Germany, was alive and well on American and British shores.

While pro-Nazi, anti-Jewish organizations such as the German-American Bund and anti-Semitic spokesmen such as Father Charles Coughlin kept up a stream of homegrown hatred, the U.S. State Department and Assistant Secretary of State Breckinridge Long were doing everything in their power to restrict the number of Jewish refugees allowed into the United States.

Despite the “official” line that to permit vast numbers of immigrants to enter the country would exacerbate the already difficult, Depression-caused unemployment scene, it was a pernicious strain of American anti-Semitism that led to the extinguishing of Lady Liberty’s lamp for those most in need of it. Even President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who secretly sympathized with the plight of the Jews, was compelled to do little to change the situation for fear that an anti-immigrant Congress would derail some of his pet legislative programs.

Once America entered the war, the Nazis’ persecution and killing of the Jews accelerated and, despite pleas from Jewish leaders who knew what was happening in the death camps, it was years before the U.S. mounted any military actions against the camps.

Only two air raids late in the war—against Auschwitz and Buchenwald—were carried out by the Allies, but they were insignificant in terms of slowing down the deaths and persecutions. Only when the Red Army overran Auschwitz in January 1945 did the full horror of the camps become public knowledge. By then, it was too late to save millions of human beings who had already been exterminated.

Why We Watched is a big, important book that asks—and answers—some disturbing questions. It is an uncomfortable read, but one that is essential if we are to understand the full meaning of World War II and the Holocaust.

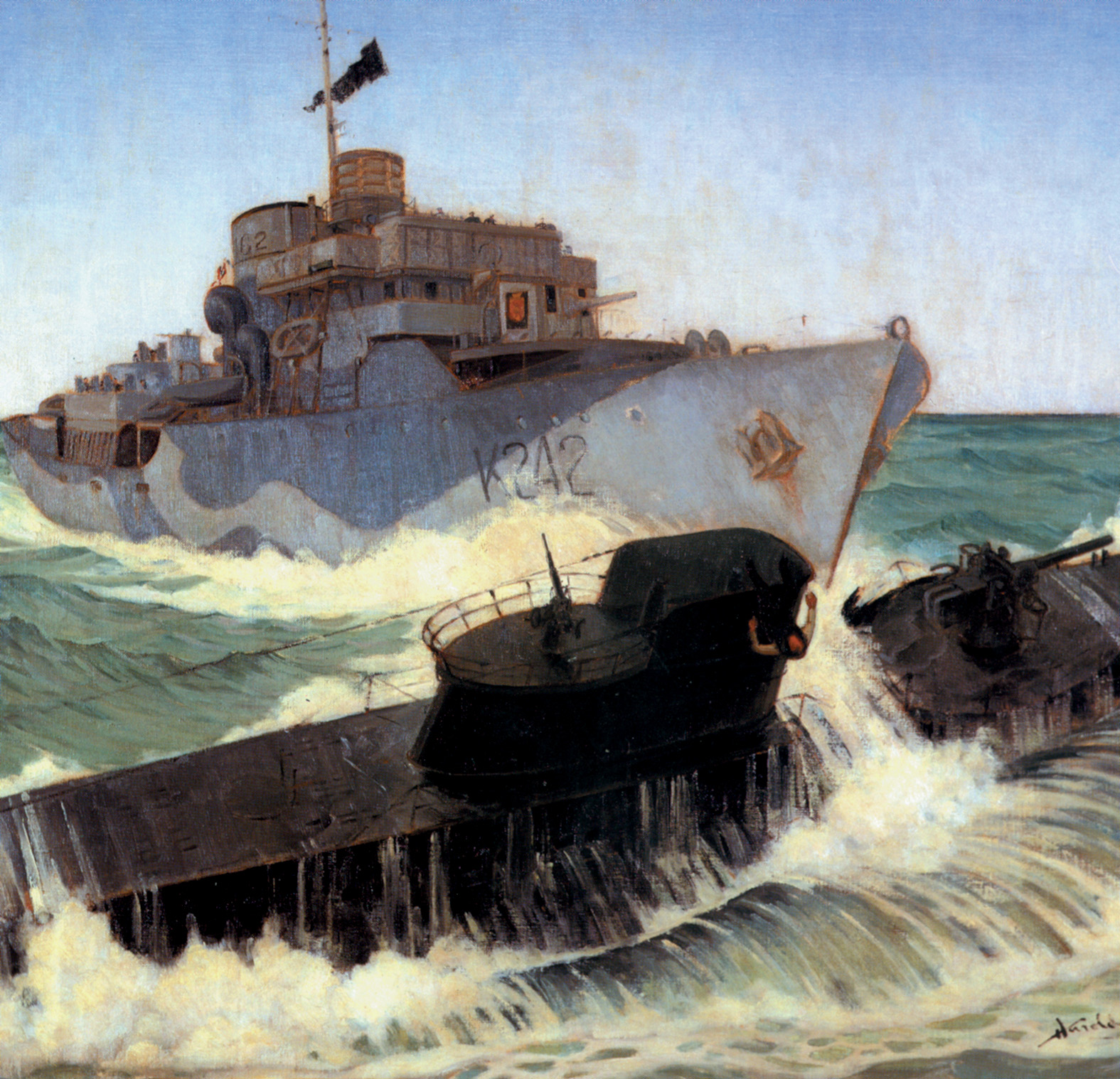

A Tale of Two Subs: An Untold Story of World War II, Two Sister Ships, and Extraordinary Heroism, by Jonathan J. McCullough, Grand Central Publishing, New York, 2008, 294 pp., photographs, index, hardcover, $26.99.

A Tale of Two Subs: An Untold Story of World War II, Two Sister Ships, and Extraordinary Heroism, by Jonathan J. McCullough, Grand Central Publishing, New York, 2008, 294 pp., photographs, index, hardcover, $26.99.

One of the most moving stories of hardship, courage, and personal sacrifice in World War II is revealed in McCullough’s A Tale of Two Subs.

On November 19, 1943, Navy Captain John Philip Cromwell, a high-ranking officer aboard the stricken U.S. submarine Sculpin, under attack by Japanese forces, chose to go down with the sub rather than try to escape.

The reason for his decision: he knew that U.S. Naval Intelligence had broken Japan’s secret codes and feared that, if he were captured and tortured, he might reveal that information and endanger the entire codebreaking operation. For his selfless courage, Cromwell was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. Fortunately, 21 of Sculpin’s crew managed to escape from the sub and were picked up by a Japanese ship.

Sculpin’s sister sub, the USS Sailfish, was involved in a tragedy of a different sort. Her captain, Bob Ward, caught sight of a Japanese convoy and opened fire, sinking the aircraft carrier Chuyo, aboard which the Sculpin survivors were being held.

Basing his riveting book on official records, recently declassified sources, and interviews with the few survivors still alive, the author provides a detailed picture of day-to-day life aboard the submarines, the palpable fear when they underwent depth charge attacks, and how the survivors were treated by their captors. The twin stories of the Sculpin and Sailfish are examples of extreme wartime heroism coupled with terrible tragedy.

Onward We Charge: The Heroic Story of Darby’s Rangers in World War II, by H. Paul Jeffers, NAL Caliber, New York, 2008, 312 pp., photographs, softcover, $15.00.

Onward We Charge: The Heroic Story of Darby’s Rangers in World War II, by H. Paul Jeffers, NAL Caliber, New York, 2008, 312 pp., photographs, softcover, $15.00.

The name William Orlando Darby is legendary, for few military units in history were as closely associated with their commander as were the U.S. Rangers to Colonel Darby. In Jeffers’s sparkling biography of the man, we come to know the Fort Smith, Arkansas, native as a flesh-and-blood human being, not just a wartime hero. Delving into Darby’s past as a teenager who himself had confidently predicted his own greatness, Jeffers takes the reader off to West Point and into the Army’s last horse artillery unit, where the young officer greatly impressed his superiors.

Seeing in their British allies the effectiveness of commando units, the U.S. Army decided to form one of their own. General Dwight D. Eisenhower personally sent Brig. Gen. Lucien K. Truscott to Britain to study the commando training methods.

Soon, Truscott ordered the 34th Infantry Division to form a “commando-like unit” made up of volunteers. Only the most rugged individuals were selected. Training placed considerable emphasis on close-in, hand-to-hand combat, stamina, aggressiveness, and self-reliance, as well as on a broad variety of skills: the use of various firearms, mountaineering, boating, scouting, electrical engineering, demolitions, and even the ability to repair radio equipment.

Those who passed the rigorous standards were admitted to the battalion, which was formed in Northern Ireland. Major William Darby was selected to command the outfit, which Truscott had named “Rangers.” Thus was born one of the most storied military units in American history.

The superbly trained unit soon experienced its baptism of fire. In October 1942, Darby’s 500 Rangers left Northern Ireland and were shipped to Scotland to prepare for Operation Torch, the invasion of North Africa. Leading the 1st Infantry Division’s landings at Arzew, the Rangers softened up the Vichy French-held beachhead and secured an entry point onto the African continent. Much of Operation Torch’s success can be attributed to what the daring Rangers accomplished.

In May 1943, the Ranger concept was expanded to add two new battalions, and Ranger training for the volunteers was conducted in North Africa. Additional battalions would later be added to bolster the Allied landings in Normandy.

Jeffers goes on to describe the other battles that would follow, at Gela in Sicily, Monte Difensa in Italy, the Anzio beachhead, and the harrowing fight for Cisterna. It was at Cisterna in late January 1944 that the Ranger force was cut to pieces.

Distraught over the annihilation of his 1st and 3rd Battalions, Darby became a commander without a command. He was soon picked up by the 10th Mountain Division and made assistant division commander, helping to spearhead the Fifth Army’s lightning drive into northern Italy.

The war in Italy was within a day or two of ending when, on April 30, 1945, while standing with a group of officers and enlisted men in a town at the northern end of Lake Garda, Darby was struck by a tiny piece of shrapnel from a shell fired by a German 88. The fragment pierced his heart, killing him nearly instantly.

Although Darby was dead, his creation lived on. Today, U.S. Army Rangers are among America’s elite fighting forces. And they continue to carry on the traditions that Darby began over six decades ago.

The Day of the Panzer: A Story of American Heroism and Sacrifice in Southern France, by Jeff Danby, Casemate, Philadelphia, 2008, 365 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $32.95.

The Day of the Panzer: A Story of American Heroism and Sacrifice in Southern France, by Jeff Danby, Casemate, Philadelphia, 2008, 365 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $32.95.

As author Danby says in the preface, “An entire American army stormed the French Riviera one hot summer day in August 1944. Accompanied by British paratroopers and supported by a vast air force, the army was augmented with French infantry and armored divisions…. Up until that moment, it was the second largest amphibious landing of the war.”

Yet, this campaign, dubbed Operation Anvil, has been maligned and minimized by some historians who have disparagingly tagged it the “Champagne Campaign,” as though it were a lark compared to the “real” fighting taking place across northern France.

As Danby makes clear in this, his first book, nothing could be further from the truth. Carefully chronicling the entire operation that was to have supplemented the Normandy invasion, Danby pays special attention to the role played by his grandfather’s unit, the 756th Tank Battalion, attached to the 3rd Infantry Division. Through his well-wrought prose, Danby paints a detailed picture of deadly fighting and stunning victory.

Expecting a stalemate on the beaches akin to that which marred the Anzio operation in Italy, the Allied planners were pleasantly surprised at the ease of landing and the swift victories that followed. But as the Allies moved northward all the way to the Maginot Line along the French-German border, they encountered a stubborn, skillful enemy who fought bitterly for each village, town, and bridge. Each mile of success was paid for in blood by the attackers.

In Day of the Panzer, the reader will gain a new appreciation for the grand sweep of Operation Anvil and the hard fighting that took place at company and platoon levels.

The Rise of the Wehrmacht: The German Armed Forces and World War II, by Samuel W. Mitcham, Jr., Praeger Security International, Westport, Conn., 2008, 2 volumes (724 pp.), photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $125.00.

The Rise of the Wehrmacht: The German Armed Forces and World War II, by Samuel W. Mitcham, Jr., Praeger Security International, Westport, Conn., 2008, 2 volumes (724 pp.), photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $125.00.

Covering the spectacular ascendancy of the Wehrmacht from October 1934 through the end of the Battle of Stalingrad in January 1943, Samuel Mitcham’s detailed and exhaustive study of the Germany military is an essential two-volume work for anyone wanting to know how a country half the size of Texas nearly conquered the world. The book does not confine itself to the German Army, but also presents in-depth analyses of the German Navy, air force, and SS, and their roles in creating the most powerful war machine the world had seen up to that time.

Mitcham begins by dealing with German post-World War I rearmament in greater detail than has been done before and discusses the importance of German police forces and their role as a vital component of the military reserves. Also addressed are the previously overlooked contributions to the war effort by the Hitler Youth, which provided essential services (postal workers, farm workers, nurses, etc.) to the German infrastructure and freed up more men for the combat formations.

Of great interest, too, is the author’s detailing of German military doctrine and the concepts of Kesselschlacht (the encirclement and annihilation of the enemy) and Blitzkrieg (lightning war).

He also explains the problems faced by the Wehrmacht because of its too-rapid expansion. This expansion was far swifter than the German generals intended and resulted in a host of problems, especially in terms of shortages of equipment and qualified officers.

Besides being a valuable reference work, The Rise of the Wehrmacht makes for fascinating reading about how a mighty force was raised and then brought to ruin.

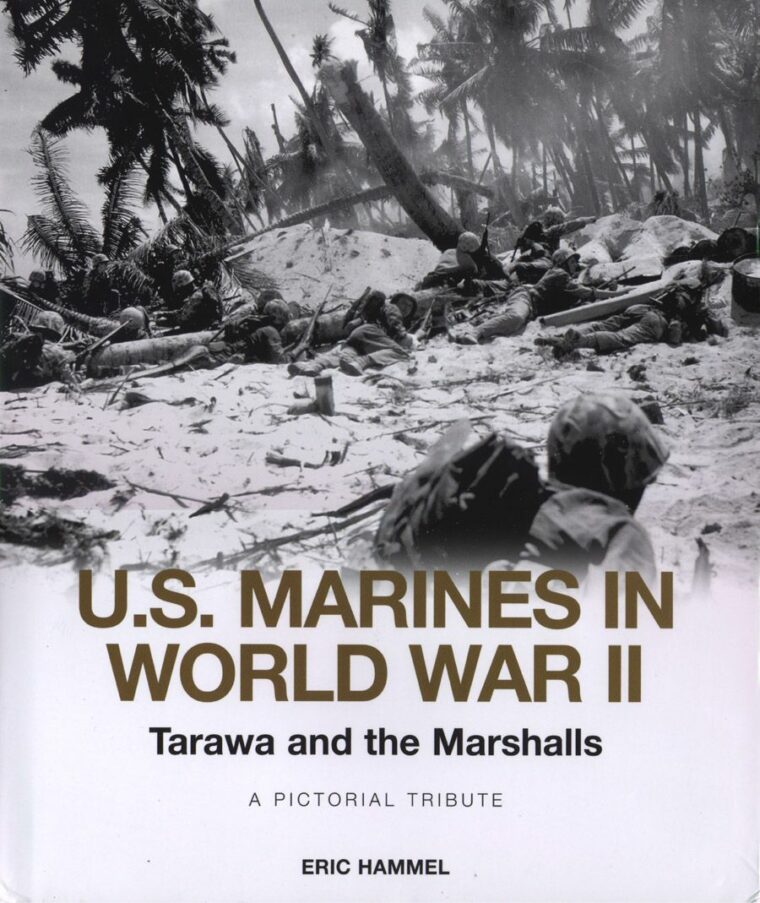

U.S. Marines in World War II: Tarawa and the Marshalls, by Eric Hammel, Zenith, Minneapolis, 2008, 128 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $35.00.

U.S. Marines in World War II: Tarawa and the Marshalls, by Eric Hammel, Zenith, Minneapolis, 2008, 128 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $35.00.

Eric Hammel continues his pictorial tributes to the U.S. Marine Corps with this handsome, large-format volume that captures the struggle, sacrifice, and determination required to wrest these important Pacific islands from a dedicated enemy. As Hammel, the skilled author of 30 books of military history, points out, some of the biggest battles fought by the Marines during World War II took place on tiny islands scattered throughout the Western Pacific. Among these, the battles for Tarawa and the Marshalls stand out as some of the fiercest and most decisive of the Pacific campaign.

One of Hammel’s hallmarks is to somehow find photographs that have not been published elsewhere, and in U.S. Marines in World War II: Tarawa and the Marshalls he does not disappoint. Some 300 photographs, many never before seen, are packed into this book’s 128 pages—photos that graphically depict the closeness of comradeship and the savagery of combat.

The first half of the book is devoted to the 2nd Marine Division’s landing on Betio Island in the Makin and Tarawa atolls on November 20, 1943, in an operation known as Galvanic. Assured that the island’s defenses had been pounded into dust by naval and aerial bombardment, the Marines discovered to their dismay that the enemy was alive and well and waiting for their amphibious approach. Three days of incredibly intense fighting secured the island for the Allies, at the cost of 600 Marines and sailors dead and more than 2,000 wounded. The Japanese paid an even heavier price: some 5,000 dead, with only a handful of survivors.

Then it was on to the Marshalls. Ninety-six islands make up the chain, and the Japanese had installed 28,000 troops to defend them. Learning that the enemy had stationed most of his troops on Wotje, Mille, Maloelap, and Jaluit Atolls, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander in chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, decided to bypass them and strike at the less defended islands of Kwajalein, Eniwetok, Majro, Roi, and Namur.

Although fewer enemy soldiers occupied these specks of land, they did not defend them with any less determination. After days of intense and brutal close combat, the defenders were finally overwhelmed by Marine firepower and sheer guts. The United States was one more atoll closer to Japan and the end of the war.

Hammel’s superb book captures all the horror and heroism that have made the Marines’ unrelenting march across the Pacific legendary.

Short Bursts

G.I. Joe in France: From Normandy to Berchtesgaden, by J.E. Kaufmann and H.W. Kaufmann, Praeger Security International, Westport, Conn., 2008, 235 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $49.95.

G.I. Joe in France: From Normandy to Berchtesgaden, by J.E. Kaufmann and H.W. Kaufmann, Praeger Security International, Westport, Conn., 2008, 235 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $49.95.

Although neither the title nor the cover photo of a Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighter convey it, this is a book about American paratroopers, pure and simple. And a fine book it is, too.

Concentrating primarily on the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions, the authors take the reader from the units’ stateside training, deployment overseas, and into their various operations and battles from, as the subtitle suggests, Operation Overlord to the Nazis’ alpine hideout at the end of the war.

But the march to victory was no walk in the park. The problems of supply and relief often exacerbated difficult conditions in the field, while incompetent line officers raised doubt and fear among the men in the ranks.

Using interviews and memoirs in addition to primary and secondary sources, the authors shed light on what an emotional shock the strain of combat was on the paratroopers. Although an incomplete telling of the paratroopers’ story (the history of the 17th Airborne Division is curiously overlooked, and airborne operations in Sicily and Italy are given only passing reference), G.I. Joe in France is still a worthwhile look into the minds and personal lives of the men who dropped from the sky to tackle the enemy.

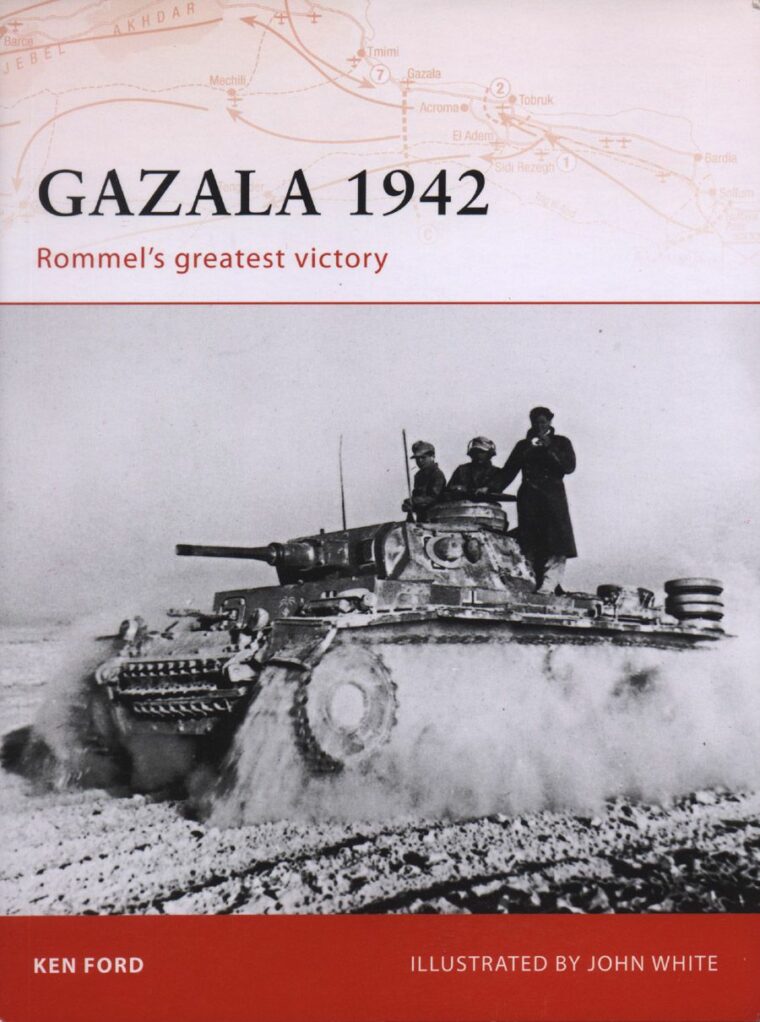

Gazala 1942: Rommel’s Greatest Victory, by Ken Ford, Osprey, Oxford, United Kingdom, 2008, 96 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, softcover, $19.95.

Gazala 1942: Rommel’s Greatest Victory, by Ken Ford, Osprey, Oxford, United Kingdom, 2008, 96 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, softcover, $19.95.

For the British, German, and Italian Armies, the first major battles of World War II began in June 1940 in an unlikely place, the inhospitable sands of Libya, in North Africa.

Back and forth across this wasteland battled the forces of General Sir Archibald Wavell and Erwin Rommel, with each, at the end of a very long supply line, trying to gain the upper hand. Although both victorious and defeated in several engagements, Rommel and his Afrika Korps (later enlarged to become Panzerarmee Afrika) refused to give up, even when it appeared he had no chance of winning.

In May 1942, Rommel assaulted the British positions on the Gazala Line, pinning down the British in the north and outflanking French positions at Bir Hacheim. The “Desert Fox” secured his reputation as being a wily and dangerous opponent when he encircled the main British positions and then destroyed their counterattacks, eventually driving the British back and inflicting heavy losses.

It was a devastating defeat for the Allies and led to the surrender of the fortress of Tobruk and the eventual arrival of the Americans in North Africa six months later. Ford’s book is a brief but masterful study of Rommel at the height of his powers as he swept the British Eighth Army back to the site of their decisive stand at El Alamein.

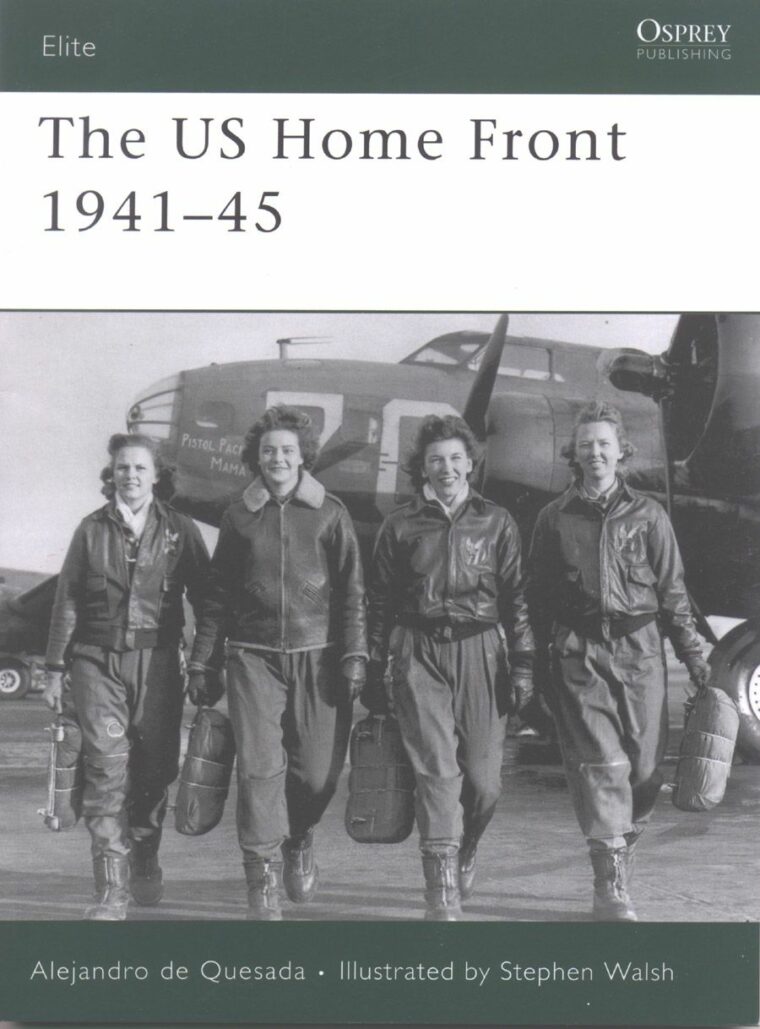

The U.S. Home Front, 1941-45, by Alejandro de Quesada, Osprey, Oxford, United Kingdom, 2008, 64 pp., photographs, illustrations, bibliography, index, softcover, $18.95.

The U.S. Home Front, 1941-45, by Alejandro de Quesada, Osprey, Oxford, United Kingdom, 2008, 64 pp., photographs, illustrations, bibliography, index, softcover, $18.95.

When one thinks of World War II, the common image is of combat on far-flung battlefronts. But there was another equally important front—the one at home.

Virtually the entire United States was united in a common goal to do whatever was necessary to ensure victory. Millions of ordinary citizens supported national preparedness and contributed unselfishly to the total American effort to win the war.

In this compact, highly interesting book, Florida-based writer Alejandro de Quesada describes the wide range of auxiliary, patriotic, humanitarian, and other organizations that sprang up all over America during the war years, everything from Cadet Nurses to the Civil Air Patrol to volunteer submarine hunters and air raid wardens, and the nearly forgotten Women’s Land Army, the Victory Corps, and Relief Wings, Inc.

Also featured are some of the less honorable aspects, such as the internment of Japanese-American citizens and the rise of homegrown fascists such as the German-American Bund.

De Quesada’s snapshot of the American home front fills in the blanks and reinforces the idea that a nation’s total commitment and undivided support is vital if it wishes to win a war.

As history would later reveal, neither Churchill nor Roosevelt held any strong interest in human rights efforts toward anyone during the war. The flattering books and films that were put forth decades later were more a political pean than any attempt at real history. Judging by events since, very few attitudes have changed among government since regarding the moral dimensions of international affairs.