By Joshua Shepherd

I can assure you that he has a military mind indeed and in adding experience to the theory he already has, he will become a person of distinction,” Maj. Gen. Louis-Joseph, Marquis de Montcalm, wrote in a dispatch to French authorities in the fall of 1758 on behalf of his young aide-de-camp, Louis Antoine de Bougainville. The glowing letter of introduction prophesied the brightest of futures for a young staff officer already accustomed to notoriety. “I look on him as one of those to whom the Ministry of War should pay the most particular attention.”

Louis Antoine de Bougainville would indeed experience a remarkably meteoric rise from his modest origins. Born November 12, 1729, to Pierre Yves de Bougainville, a middling notary in the Paris Courts of Justice, the young Bougainville was orphaned as an infant. His mother died soon after his birth, and he was raised by the Herault de Sechelles, a wealthy acquaintance who took an interest in the boy. Among Herault’s friends was famed mathematician Jean Le Rond d’Alembert, who perceived in the precocious Bougainville a latent genius in need of academic nurture.

A Prototypical Renaissance Man

D’Alembert encouraged his studies and Bougainville ultimately was trained as an attorney at the University of Paris. He proved, however, to be a prototypical renaissance man, excelling in diverse fields of study but particularly in mathematics. Though a comfortable career awaited him at the bar, Bougainville continued his studies in his spare time and in 1753 presented the first volume of his book Treatise on Integral Calculus, considered an innovative work whose originality drew favorable evaluation from European scholars.

D’Alembert encouraged his studies and Bougainville ultimately was trained as an attorney at the University of Paris. He proved, however, to be a prototypical renaissance man, excelling in diverse fields of study but particularly in mathematics. Though a comfortable career awaited him at the bar, Bougainville continued his studies in his spare time and in 1753 presented the first volume of his book Treatise on Integral Calculus, considered an innovative work whose originality drew favorable evaluation from European scholars.

Bougainville’s temperament and ambition nevertheless drove him to pursue service in the military, where he gained experience in staff positions, ultimately joining the ranks of the Mousquetaires Noirs, an elite dragoon regiment. The brilliant young staff officer caught the eye of his superiors and in 1754 was appointed as secretary to the French ambassador to the Court of St. James. Bougainville added to his reputation by polishing his English and circulating among military officers and the intelligentsia. Though serving in London for only a few months, he made such an impression on his hosts that he was installed a fellow in the Royal Society for his work in calculus.

High Praise from Montcalm

Official relations between the governments of France and Great Britain were unfortunately not so cordial, as the two powers were then locked in a de facto war in their North American possessions. Border tensions had degenerated to armed confrontation in 1754, and the conflict escalated until 1756, when war was officially declared and France deployed a fresh army to Canada under the command of Montcalm. Strongly recommended by his previous superiors, Bougainville was promoted to the rank of captain and assigned to Montcalm’s staff.

The pair formed a close bond from the outset. Bougainville relieved his commander from such mundane tasks as correspondence and journal entries with such fidelity that Montcalm came to regard him as a son. “He is bright and witty,” Montcalm informed his wife, “and makes things easier for me by correctly anticipating my wants…. I prize his varied talents highly.”

Montcalm opened an offensive in August 1756 by besieging the vital British trade port of Fort Oswego on Lake Ontario. After two days of desultory action, Montcalm’s batteries opened fire and Oswego’s unfortunate commander was cut in half by solid shot from a 12-pounder. Chosen for his fluency in English, Bougainville advanced under a flag of truce to demand surrender, which was quickly proffered by a rattled garrison. It was, however, a victory that afforded tarnished laurels for the French officers. Subsequent to the surrender, French-allied tribesmen got out of hand and commenced tomahawking prisoners. Before the brutal melee ended, upward of 100 had been killed.

Intelligence Gathering During the French & Indian War

The senseless slaughter at Oswego disabused idealistic officers such as Bougainville of the notion that European sensibilities would be honored in the horrific combat conditions of the North American wilderness. The Indians were, at best, unreliable auxiliaries—Bougainville likened them to mosquitoes—yet they were an integral component of the French war effort. Tribal practices such as scalping, the torture of captives, and ritual cannibalism offered a “horrible spectacle to European eyes,” wrote Bougainville, who at the same time acknowledged the Indians’ skill as scouts and irregulars as “a necessary evil.” Consequently, even reluctant officers such as Bougainville were expected the help maintain tribal alliances. A bemused Bougainville eventually attended a tribal feast where he performed an awkward dance and was welcomed by his Caughnawaga hosts.

During fall 1756, Bougainville participated in several scouting parties that headed south to stage ambushes and gather intelligence on British strength in the vicinity of Fort William Henry at the head of Lake George. The following summer, Montcalm launched an expedition down the Lake Champlain corridor and invested the British fort. After a week-long formal siege, Bougainville, blindfolded by English officers, entered the fort to demand surrender. Despite a spirited defense, the English were forced to capitulate. Montcalm granted generous terms, paroling the English on the field and assigning them an escort back to their own lines. But in the march from the fort, tribesmen eager for booty, scalps, and prisoners attacked the column, and again a massacre ensued during which more than 185 English lost their lives.

Requests for Material Support Falling on Deaf Ears

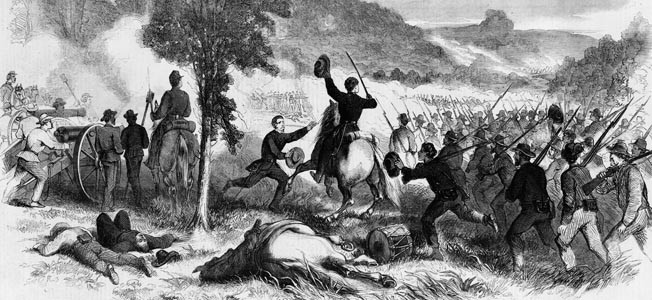

Despite the victory, Montcalm was obliged to fall back on Fort Carillon due to critical supply and manpower shortages. By July 1758, a massive British army of more than 12,000 troops arrived to find Montcalm’s 3,500 men dug in behind extensive fortifications. The British commander, General James Abercromby, spurned the admonitions of his subordinates and threw his men headlong at the French lines. What resulted was nothing short of disaster; 1,900 English troops were felled, and Abercromby’s battered army retired entirely demoralized. The French had likewise sustained considerable casualties amounting to 400 men. Among them was Bougainville, who had suffered a head wound inflicted by enemy musketry. “Never had a victory been more especially due to the finger of Providence,” he said.

Such losses in manpower could be ill afforded, and in the face of a worsening supply crisis Bougainville was dispatched to France that autumn in the hope that personal pleas would impress on the government the desperate nature of the situation in Canada. Although Bougainville was feted as a hero and made a chevalier in the Order of St. Louis, his requests for greater material support of the war in North America largely fell on deaf ears. France was embroiled in a global conflict that taxed its resources to the limit, and affairs in Europe quite simply outweighed all other considerations.

By the spring 1759, Montcalm held what he considered a tenuous grip on New France. Even the return of the newly promoted Colonel Bougainville with 300 regulars was but little solace. Montcalm had been forced to fall back to Quebec and on June 26 was stunned to learn that a British expedition under the command of Maj. Gen. James Wolfe had made the treacherous journey up the St. Lawrence River to take up positions on the south side of the river. What ensued was a two-month stalemate. Wolfe failed to breach Montcalm’s lines east of the city and to the west Bougainville commanded a flying column of picked regulars that made assault in that sector seem improbable. But on September 12, Wolfe discovered that Bougainville would be occupied that night supervising a supply convoy from Montreal.

Early on the morning of September 13, Bougainville caught wind of an English landing and immediately set his men in motion for Quebec. By the time he arrived before the city, it was too late. Wolfe had launched a daring night amphibious operation, brought up seven battalions, and crumpled Montcalm’s hastily formed lines with several devastating volleys. Quebec was soon surrendered and Montcalm, Bougainville’s beloved mentor, was mortally wounded.

The English Tighten Their Stranglehold Across Canada

With Quebec secure, the English slowly began tightening their stranglehold across the rest of Canada. Despite a bold, if brief, offensive in the spring of 1760, it was all but over for French arms. Bougainville and the rest of the army, reduced to just 10 hollow battalions, were maneuvered into the confines of Montreal and cut off by three converging English armies. On September 8, 1760, Canada was surrendered.

Bougainville returned to Europe where, under the terms of his parole, he was unable to participate in active military operations and saw limited service in France and Germany until officially exchanged in May 1762. However, Bougainville, ambitious as ever, had already seized upon a grand scheme then afloat in the French court for the colonization of the Falkland Islands. The Isles Malouines, as the French referred to them, proved a boondoggle.

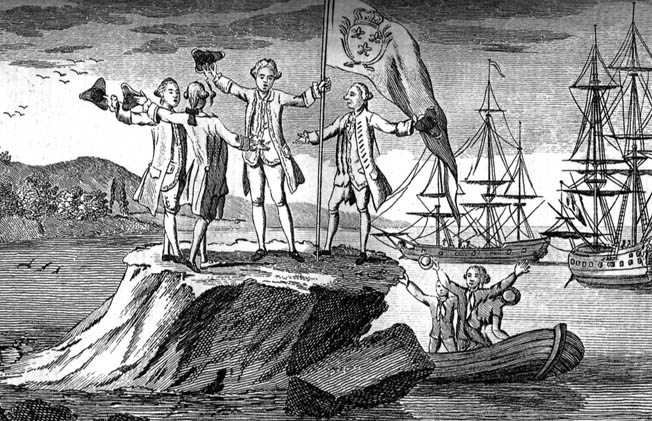

Though both Spain and England laid dubious claim to the uninhabited islands, Bougainville, who secured a transfer to the navy with the rank of captain, was authorized by Louis XV to undertake their colonization so long as the venture was backed by private funding. Bougainville succeeded in landing colonists on East Falkland in January 1764, but the following year a British colony appeared on West Falkland and the Spanish government grew restless at the prospect of two foreign settlements so near its own South American possessions.

Circumnavigating the Globe

Fear of alienating Spanish allies prompted French officials to abandon the project, and in April 1766 Bougainville met with Spanish envoys in Madrid to surrender French claims to the Malouines. For Bougainville, another venture suitable to his talents soon materialized. French navigators had yet to circumnavigate the globe, and Bougainville advanced a plan to do just that. With royal funding, he was assigned the frigate Boudeuse and the supply ship Etoile. On November 15, 1766, Bougainville sailed from Nantes with truly monumental orders: “Proceed to the East Indies by crossing the South Seas between the tropics.”

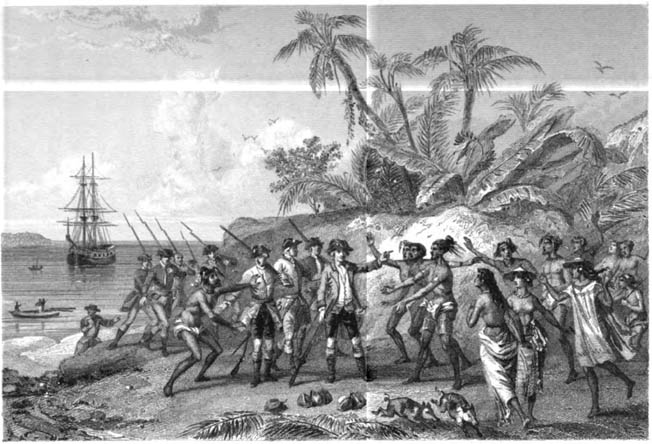

It was, indeed, an epic voyage. Passing the treacherous Straits of Magellan in January 1768, Bougainville emerged into the Pacific and collected scientific data in waters previously sailed by only a handful of Europeans. One discovery was of particular note: a flowering vine native to South America, which the expedition’s botanist promptly christened the bouganvillea. The expedition saw much of the South Pacific, including Tahiti, the New Hebrides, and the Solomons, the largest of which was likewise named for Bougainville. Though making claim to a number of islands in the name of his sovereign, he was intent to avoid armed confrontation with hostile islanders “to prevent our being dishonored by such an abuse of the superiority of our power,” he wrote. Such caution paid off. Of 400 crew members, his two ships lost just nine men during the two-year voyage.

Reaching France in March 1769, Bougainville was the rage of Paris and immediately set to work penning an account of the expedition, A Voyage Round the World, which was published in 1771. Already considered a brilliant mathematician and distinguished military officer, his newly acquired status as a world-renowned navigator landed him the position of secretary to King Louis XV.

Married at 51

After a renewed outbreak of hostilities with Great Britain resulting from France’s recognition of American independence in 1778, Bougainville was assigned as Captain of the Guerrier in the squadron of Vice Admiral Charles Hector, Comte d’Estaing, which sailed for America in April. Bougainville saw close to two years of service off the American coast and was exasperated by what he considered his commander’s inept decisions. D’Estaing’s squadron made a less than illustrious record in American waters, bungling an abortive blockade of British-held New York and participating in the disastrous allied assault on Savannah in the fall of 1779.

Poor health and disillusionment with navy polices prompted Bougainville to resign his commission on January 16, 1780. He was granted the sinecure rank of general in the army and, with his pride much assuaged, returned to the service by the end of the year. He took advantage of the hiatus to tend to his much-neglected personal life, and on November 27, the 51-year-old Bougainville finally took a bride, the young daughter of a fellow naval officer. His marriage to Flore de Montendre, which produced four sons, proved to be a happy union despite his long absences at sea.

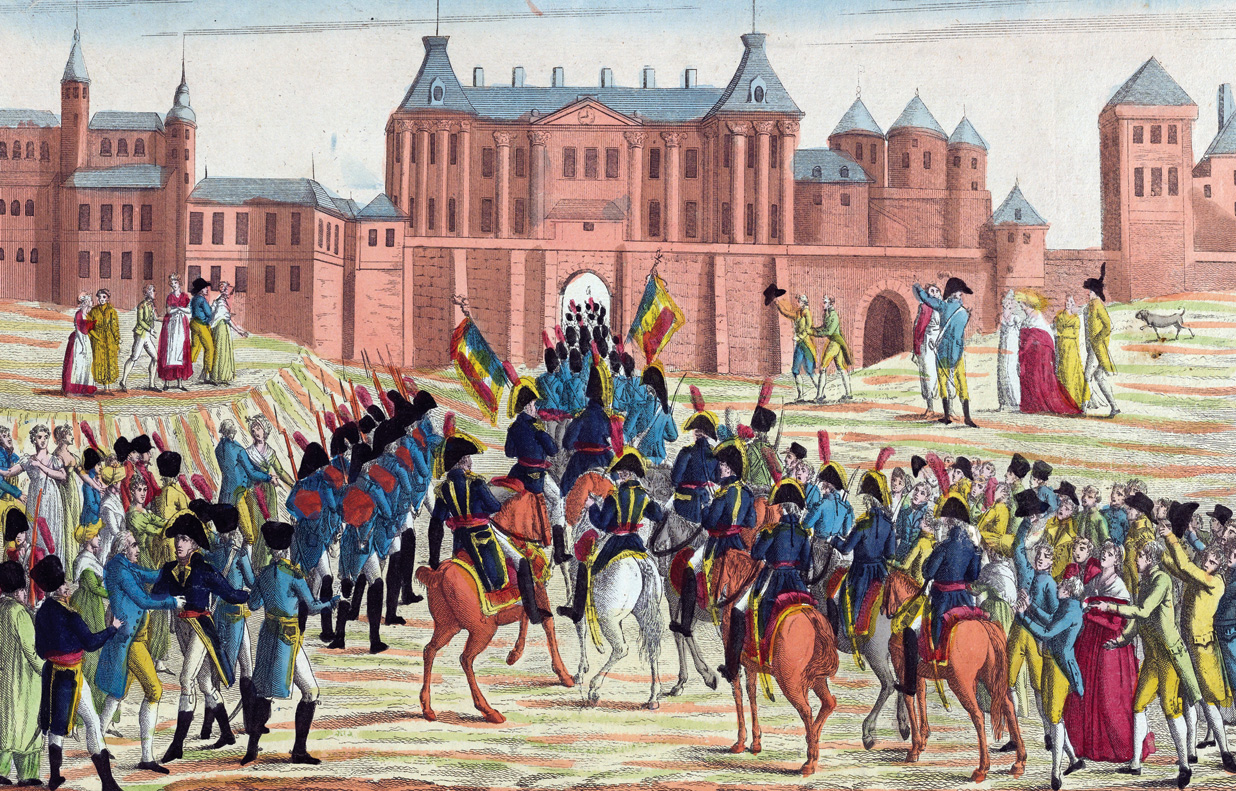

Recalled to active service, Commodore Bougainville was given command of eight ships in the fleet of Admiral François Joseph, Comte de Grasse, which cruised the West Indies until August 1781 when the fleet headed north to cooperate with joint Franco-American operations in Virginia. De Grasse’s fleet entered Chesapeake Bay, effectively cutting off the English army of Lord Charles Cornwallis in Yorktown. On September 5, the French were at anchor with many of their men on shore duty. Caught unawares by the British fleet of Admiral Thomas Graves, which suddenly appeared at the mouth of the bay, de Grasse frantically got his ships underway.

“Now That’s What I Call ‘Combat’!”

The French emerged from the Chesapeake in a scattered line of battle, and Bougainville, commanding the lead ships, was far ahead of the rest of the fleet. Although Graves held the weather gauge, he hesitated and, to the consternation of his officers, inexplicably granted the French fleet additional time to partially close up their disjointed line and prepare for battle.

The brunt of the fighting that followed fell on Bougainville’s lead squadron. He met the oncoming English fleet with his 80-gun flagship, Auguste, and crippled Admiral Francis Drake’s 70-gun Princessa with a flurry of broadsides. As the Auguste closed to within small-arms range, Drake maneuvered clear but exposed the Terrible, a 74-gun ship-of-the-line but the most decrepit vessel in the English fleet. Bougainville gave her such a pounding that she fled the scene and was later scuttled. Watching the action from afar, de Grasse was beside himself. “Now that’s what I call ‘combat,’” he later told Bougainville, “For a while I thought you were going to board!”

Stunned by the ferocity of the scrap with Bougainville’s ships, Graves pulled off and de Grasse reentered the Chesapeake. All hope was lost for the British. Graves fled to New York to refit his battered fleet, and Cornwallis was forced to surrender Yorktown on October 19, 1781. De Grasse gave credit for the momentous naval victory to his subordinate, informing General George Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette that “the laurels of the day belong to de Bougainville.”

Military Contributions Lost To Time

War lingered on, however, in the West Indies, where the French met with disaster the following spring. En route to operations off Jamaica, de Grasse and Bougainville crossed paths with the fleet of Admiral George Rodney, a tough veteran who would not be as forgiving an opponent as Graves had been. For three days, the two fleets sparred and jockeyed for position. On April 12, Rodney, who took advantage of a sudden shift in the wind, attacked near the Isle des Saintes in the Dominica Passage and severed the French line at several points. Contradictory battle signals from the deck of de Grasse’s isolated flagship only added to the confusion caused by the devastating English attack. De Grasse and his beleaguered flagship were captured and the rest of the fleet, including Bougainville’s squadron, drew off.

Released by the British in August, de Grasse immediately set about to cast blame for the humiliating debacle on Bougainville. His towering flagship, Ville de Paris, was the largest warship in the world and its loss was a bitter pill for the French navy. A council of war officially cleared de Grasse and reprimanded Bougainville, but de Grasse had fallen out of favor as a result of the embarrassing episode and he was quietly forced into retirement. Bougainville, on the other hand, remained a favorite of the court and served in the navy until 1791, when he resigned as the commander of the Brest Squadron and retired with the dual ranks of admiral in the navy and field marshal in the army.

Though a close adviser to Louis XVI, Bougainville refused all further public appointments. He attempted to settle down with his family but lived a less than peaceful retirement on an estate in Normandy. Because of his strong royalist leanings, he narrowly escaped execution during the French Revolution. One of his sons died in a drowning accident in 1801, and he was widowed five years later. Napoleon, however, who had admired the great navigator since his youth, made Bougainville a count, senator, and grand officer in the Legion of Honor.

Spending his last years immersed in his studies and occasionally called upon to counsel the emperor, he died in Paris on August 31, 1811. His ashes were interred in the Pantheon, where a simple memorial inscription reads: “Homage to the great men who deserve well of their country.”

Ironically, the aged veteran who spent nearly four decades in service to the French monarch is nearly forgotten for his military exploits. Irrepressibly good humored, Bougainville expected as much. Once asked about his legacy, Bougainville wryly pointed to the lovely vine that he brought back from his circumnavigation. He quipped, “I am also placing hope for my reputation in a flower.”

“I am also placing hope for my reputation in a flower.”

He was wise to do so… even though few people today would know for whom the flower is named. (I didn’t.)